Abstract

Ionizing radiation (IR) plays a key role in both areas of carcinogenesis and anticancer radiotherapy. The ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) protein, a sensor to IR and other DNA-damaging agents, activates a wide variety of effectors involved in multiple signaling pathways, cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair and apoptosis. Accumulated evidence also indicates that the transcription factor NF-κB (nuclear factor-kappaB) plays a critical role in cellular protection against a variety of genotoxic agents including IR, and inhibition of NF-κB leads to radiosensitization in radioresistant cancer cells. NF-κB was found to be defective in cells from patients with A-T (ataxia-telangiectasia) who are highly sensitive to DNA damage induced by IR and UV lights. Cells derived from A-T individuals are hypersensitive to killing by IR. Both ATM and NF-κB deficiencies result in increased sensitivity to DNA double strand breaks. Therefore, identification of the molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-κB signaling in tumor response to therapeutic IR will lead to a better understanding of cellular response to IR, and will promise novel molecular targets for therapy-associated tumor resistance. This review article focuses on recent findings related to the relationship between ATM and NF-κB in response to IR. Also, the association of ATM with the NF-κB subunit p65 in adaptive radiation response, recently observed in our lab, is also discussed.

Keywords: ATM, NF-κB, ionizing radiation

INTRODUCTION

Energies of both ionizing and non-ionizing forms of radiation are believed to have been prevalent in the universe long before the appearance of life on Earth. This unfriendly radioactive environment likely helped to creating the original biological molecules, cell formation, and species evolution with a “built-in” molecular system defending against radiation induced damage. Soon after Roentgen’s discovery of X-ray in 1895, ionizing radiation (IR), defined as the radiation rays containing the protons with the energy enough to produce charged ions (free radical immediate) in water, has been used in clinical settings as a powerful tool for the treatment of many human diseases. More than 50% of all cancer patients receive radiotherapy at some time during the course of anti-cancer treatment. In the United States, nearly 500,000 patients receive radiotherapy each year as an essential part of their cancer treatment. A huge body of experimental and clinical data has demonstrated a variety of intrinsic tumor sensitivity to radiotherapy, although the exact molecular mechanism causing the different radiation response is largely unknown. Clinical results show that cells lacking an intact DNA damage sensor protein ATM are hypersensitive to IR with multiple defects in the cell cycle-coupled checkpoints. Cancer incidence is increased in patients with A-T (ataxia-telangiectasia) due to the deficiency of DNA repair. In addition, modulation of another DNA-damage responsive factor NF-κB increases radiosensitivity in several tumor cell lines [1–3]. Blocking IR-induced NF-κB activation increases apoptotic response with decreased rate of cell growth and clonogenic survival [4]. These results suggest that ATM and NF-κB contribute, together or separately, to the overall cell radiosensitivity.

Although radiosensitivity of tumor cells is highly desirable for a successful radiotherapeutic cure rate, significant tumor resistance to radiation and/or chemotherapeutic agents has been observed [5–8]. IR was shown to induce an adaptive resistance in mammalian cells that is defined to be the reduced cell sensitivity to a higher challenging dose of a genotoxic agent when a smaller inducing dose had been applied a few hours earlier [9]. The molecular mechanism underlying such adaptive resistance, presumably via DNA repair and apoptosis, has not been fully explained, but essential to further improving therapeutic efficacy. Recent evidence suggests that, in addition to the activation of p53 and other DNA repair-associated pathways, NF-κB plays a key role in the activation of a signaling network that can enhance cell survival. Data reported by our group and others strongly suggest that NF-κB appears to regulate a pro-survival signaling network involving ERK, Her-2, mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme MnSOD, cell cycle elements (cyclin Bl and cyclin D1) and chaperons 14-3-3 family [84]. Therefore, NF-κB-associated signaling network likely plays an important role in the adaptive tumor resistance. Cooperation of NF-κB and ATM is evidenced by the fact that A-T patients exhibit a defect in NF-κB activation in response to treatment with a DNA-damaging compound camptothecin, a topoisomerase I poison, and ectopic expression of the ATM protein in A-T cells activates NF-κB in response to camptothecin [102]. Thus, ATM-mediated NF-κB activation contributes to the development of radioresistant phenotype in irradiated tumor cells.

This review will selectively discuss the current understanding of the relationship between ATM and NF-κB in radiation response. Recent data from literature as well as this laboratory regarding the cross-talk between ATM and NF-κB in radioresistant breast cancer cells, derived from the treatment with fractionated ionizing radiation (MCF+FIR), and immortalized human HK18 keratinocytes will also be discussed. This interaction under IR indicates an important role of ATM-NF-κB complex in adaptive radiation response, and thus, targeting this complex or its key downstream elements may promise a new approach (1) to prevent radiation therapy-associated tumor resistance, and (2) to protect normal tissue from radiation-induced injury.

ATM AND ATAXIA TELANGIECTASIA

A-T is a rare human genetic instability syndrome, seen 1 in every 40,000 live births in the USA [13], characterized by extreme sensitivity to radiation-induced DNA damage with increased cancer risk, progressive neuronal degeneration, and immunological deficiency, with a hallmark of onset in early childhood [14–17]. Because of a defect in the activation of cell cycle checkpoints or DSBs repair after irradiation, A-T cells show pronounced radiosensitivity [18–20]. Approximately one third of A-T patients develop cancer, mostly lymphoid malignancies with both B-cell and T-cell origin, and include non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and several forms of leukemia [21].

ATM was identified as the product of the gene mutated/inactivated in ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) [10, 11]. The ATM gene is located at 1lq22–23, spans more than 150 kb, and is composed of 66 exons (62 coding). The human ATM gene is expressed in a wide range of tissues as 13 kb transcript encoding a protein of 3,056 amino acids (predicted mass ~350 kD). The mouse ATM gene was shown to have 84% overall identity with the human gene [12]. ATM has sequence homology to a family of proteins, with molecular masses ranging from ~300 kD to >500 kD, that are related to the phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-kinases (PI3K). The functions of other members of this family, including DNA-PKcs (DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit), ATR (ATM-and-Rad3 related), and the newly identified ATX, are largely unknown. ATM is considered a primary transducer of cellular responses to DSBs. It is an inactive dimer or high-order multimer in undamaged cells, and is activated by rapid intermolecular phosphorylation of Ser-1981 after exposure to IR. Activated ATM, in turn, phosphorylates key factors in various damage response pathways, including p53, Mdm2, Chk2, BRCA1, SMC1, NBS1 and FancD2, resulting the activation of cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair, or the induction of apoptosis.

ATM AND IONIZING RADIATION

In eukaryotic cells, IR and other DNA damaging agents activate signal transduction pathways that rapidly affect downstream processes such as gene transcription, cell cycle progression, and DNA replication [22, 23]. ATM is crucial for the initiation of signaling pathways for DNA repair in mammalian cells following exposure to IR and other DNA-damaging agents [24, 25]. Cells derived from A-T patients and from ATM−/− mice display hypersensitivity to IR, chromosomal instability, and defects in the G1, S and G2 checkpoints [25, 26]. Although Brown et al. and other groups reported that ATM protein levels were not up-regulated following genome damage [27–29], Yuko et al. found that both the ATM mRNA and its protein product increased in normal human cells soon after they have been exposed to 10 Gy of X-rays [30]. This discrepancy was explained by the finding that ATM protein levels vary dramatically with cell cycle stage [30]. ATM mRNA appears to be present in significant quantities throughout the cell cycle, but its protein product appears to be absent at GO and reaches measurable levels only in G1 to S. These results suggest that synthesis of the ATM protein is regulated at the post-transcriptional level.

Substantial progress has been made recently regarding the mechanism by which ATM signals following exposure to IR. ATM signaling after DSBs involves a coordinated series of events that occur rapidly and collectively to activate key cellular effectors [25]. In response to DSBs, ATM is autophosphorylated at Ser-1981, which leads to the dissociation of inactive multimeric ATM (either a dimer or a higher order multimer) to initiate ATM signaling [31]. Activated ATM directly associates with MRN complex, named as such because of its three principal component proteins: MRE11, RAD50 and NBS1 [32–34]. This interaction can control signaling by influencing the ATM substrate choice [35]. In addition to MRN, other key players of the ATM substrates in response to DSBs include histone H2AX, 53BP1, MDC1, and BRCA1. These factors rapidly mobilize to the sites of DSBs and initiate an ATM-dependent signaling cascade that leads to the resolution of the break through DNA repair, or, in the case of excessive DNA damage, cell death, often through p53-mediated apoptosis.

ATM-INTERACTING PROTEINS

Although this review paper focused on ATM-NF-κB connection, it is worthy to be described briefly about the relationship of ATM with other proteins [36–40], which will provide some functional consequences of ATM with its connection pattern with other proteins. Recent studies have shown that the ATM protein kinase plays a critical role in maintaining genome integrity by activating a biochemical chain reaction that in turn leads to cell cycle checkpoint activation and repair of DNA damage. This and other functions of ATM are believed to be mediated by direct interaction and phosphorylation of major signaling proteins. Several binding partners of ATM were discovered with precise sites of binding, phosphorylation, and the importance of the binding. ATM targets include well-known tumor suppressors p53 and BRCA1, both of which play an important role in predisposition to breast cancer. ATM can directly interact with p53 causing its Ser-15 phosphorylation, thereby contributing to the activation and stabilization of p53 during the IR-induced DNA damage response [41]. In addition, two regions in ATM, one at the amino terminus and the other at the carboxy terminus, corresponding to the PI-3 kinase domain, were found to be involved in binding with p53 as well as BRCA1. An interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage was described by Shafman et al. [42], and this interaction may in part mediate radiation-induced G1 arrest. They also demonstrated that the SH3 domain of c-Abl interacts with a DPAPNPPHFP motif (residues 1,373–1,382) of ATM, which facilitates phosphorylation and activation of c-Abl by ATM [41, 42]. Nicolas et al. suggested a model in which BRCA1 acts in concert with ATM to regulate c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity [43]. Following exposure to IR, the BRCA1-c-Abl complex is disrupted in an ATM-dependent manner, which correlates temporally with ATM-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 and ATM-dependent enhancement of the tyrosine kinase activity of c-Abl.

In addition to the interaction of ATM with p53, BRCA1 and c-Abl described above, ATM also interacts with Chk1, Chk2, Rb, ATR, MLH1, RPA, and Rad51. Thus, by functioning as a hierarchical protein kinase, the ATM protein appears to act on both cell cycle signaling and on the processing of DSBs induced by radiation. ATM directly phosphorylates Thr-68 on Chk1 and Chk2 [44–45] in cells exposed to IR. The phosphorylated Chk1/Chk2 then phosphorylates Cdc25 on Ser-216 [46–48], thereby inhibiting Cdc25 phosphatase activity. The function of Cdc25 phosphatase is to convert inactive Cdc2-P to active Cdc2 by dephosphorylating Cdc2-P at Tyr-15 and Thr-14. Activated Cdc2 together with cyclin B1 promote the main players in the progression of cells though G2 phase to mitosis [45, 48, 49]. Therefore, activation of ATM following DNA damage and subsequent suppression of Cdc25 phosphatase results in suppression of cyclin Bl/Cdc2 kinase activity to cause G2 arrest.

Heather et al. further described that ATM interacts with and directly phosphorylates BLM (the gene mutated in Bloom‧s Syndrome) on Thr-99 and Thr-122 near the N-terminus of the protein [50]. These phosphorylations are physiologically significant since expression of mutant forms fails to correct radiation-induced damage in BS (Bloom’s Syndrome) cells and enhanced radiosensitivity and chromosome aberrations in control cells. As described above, although ATM interacts with several key cell signaling elements, the exact function of ATM interaction with other IR responsive factors is to be elucidated. Identification of unknown ATM-binding proteins may promise new approches to protect or cure from many genetic disorders, including cancer and A-T. Scheme 1 and 2 (following) describe a novel interacting partner (i.e., NF-κB) of ATM, based on our recent observations. The ATM-NF-κB complex might play an important role in tumor adaptive response to radiation.

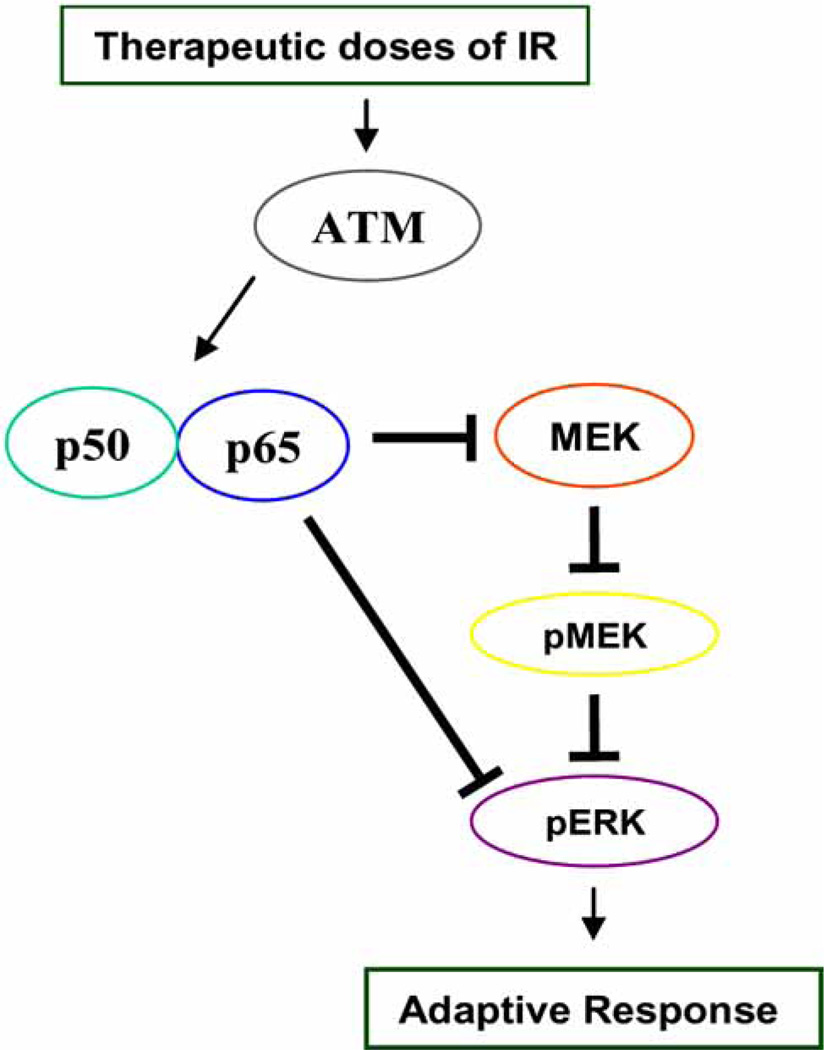

Scheme 1.

Schematic presentation of the ATM-NF-κB connection in adaptive radioresistance. In chronic response (cells with pre-irradiation), ATM interacts directly with NF-κB subunits p65 and p50, resulting in the induction of both activity and expression of NF-κB. This event causes the interaction of p65 with MEK/ERK, resulting MEK/ERK inhibition. Therefore, ATM-mediated negative regulation of NF-κB on MEK/ERK pathway may cause increased cell survival under the genotoxic conditions of a long-term therapeutic irradiation.

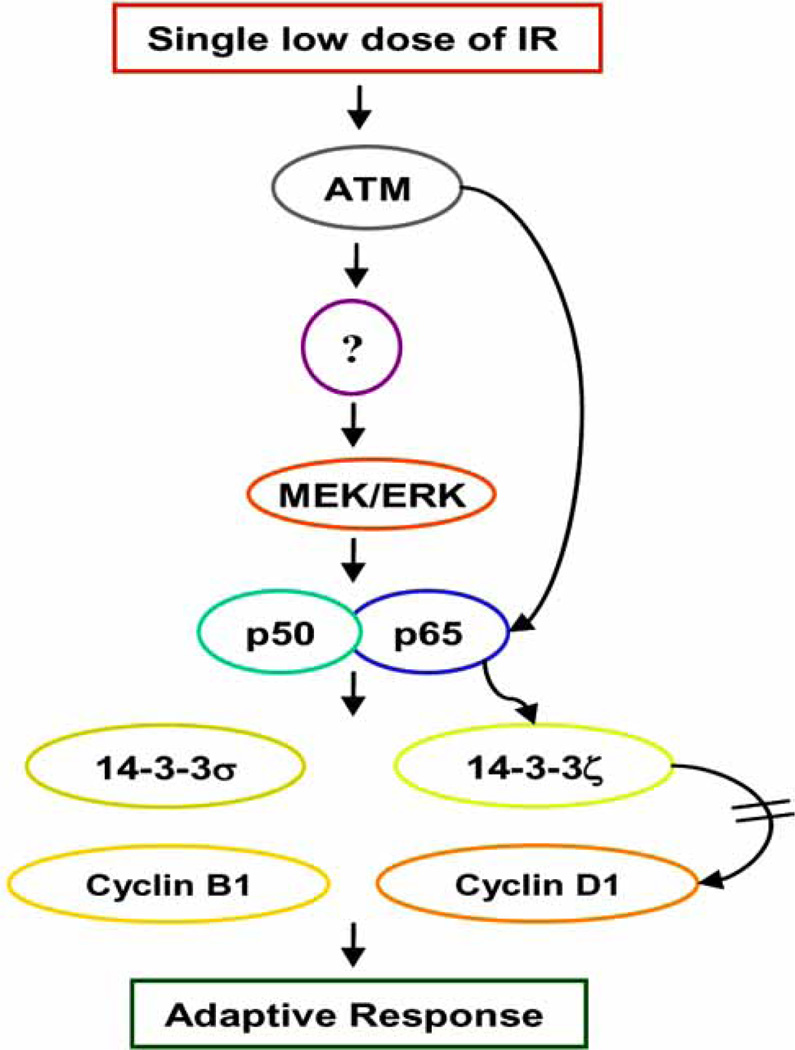

Scheme 2.

ATM-NF-κB-regulated signaling network causing the adaptive resistance to IR in normal human skin epithelial HK18 cells. Low level radiation induces ATM-NF-κB p65 interaction through NF-κB activation by an ATM-dependent fashion (ATM/unknown kinase/MEK/ERK pathway). These events result in up-regulation of 14-3-3s and cyclins, and a reduction of 14-3-3ζ-cyclin D1 complex. Overall, these results demonstrate a novel molecular events of adaptive radioresistance involving ATM-NF-κB connection in human keratinocytes.

NF-κB ACTIVATION MECHANISMS

NF-κB was first identified as a protein bound to a sequence in the immunoglobulin kappa light chain enhancer in B cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide [51]. Now, a great number of genes involved in stress responses, inflammation, pro- and anti-apoptosis are regulated by NF-κB. In mammals, the NF-κB family consists of five members of the Rel family: RelA (also called p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50/pl05 (also called NF-κBl), and p52/pl00 (also called NF-κB2). Although the heterodimer of p50 and p65 is shown to be the most abundant form of NF-κB [52], different combinations of homo- or heterodimers can be formed that are thought to determine the intrinsic NF-κB specificity and its regulation [53–56]. NF-κB DNA binding sites present in the promoter region of many genes are capable of binding p50 homodimers, p50/p65 or p50/c-Rel heterodimers, suggesting that NF-κB can regulate the expression of different effector genes [57].

Under normal conditions, the NF-κB complex is formed by a p50 homodimer or a p50/p65 heterodimer bound to a member of the IκB family [57, 58]. In the cytosol of unstimulated cells, which is being extensively investigated, the nuclear localization signal of NF-κB is effectively hidden through the non-covalent binding with IκB. Members of the mammalian IκB family include IκBα,IκBβ,IκBγ,IκBε,Bcl3,pl05, and p100, of which the most studied is IκBα. Following stimulation, DNA-binding subunits p50 and p52 that carry a Rel homology domain (RHD) are proteolytically released from pl05 and p100, respectively. The RHD contains a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and is involved in dimerization, sequence-specific DNA binding, and interaction with the inhibitory IκB proteins. Bc13 functions as a transcriptional activator with p50 or p52 homodimers rather than an inhibitor of NF-κB. Using various stimuli, including TNF-α, PMA, LPS, interleukins, and UV or IR, it has been well established in many cell lines that signal-induced activation of NF-κB typically occurs through phosphorylation of IκB proteins at Ser-32 and Ser-36 in IκBα, and Ser-19 and Ser-23 in IκBβ via ubiquitin-dependent protein kinase, followed by ubiquitination at nearby lysine residues and degradation by the 26S proteasome [59–61]. Upon degradation of IκB protein, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus where it either binds to a specific 10-base-pair consensus site GGGPuNNPyPyCC (Pu = purine, Py = pyrimidine, and N = any base) or interacts with other transcription factors thereby regulating gene transcription. Although it has been suggested that the degraded IκB may still be associated with NF-κB in mammalian cells, activated NF-κB typically exists as a dimeric protein, and this transcriptionally active form possesses both DNA-binding and transactivation domains. NF-κB activates transcription from a wide variety of promoters, including that of its own inhibitor IκBα. The newly synthesized IκBα enters the nucleus and removes NF-κB from its DNA-binding sites and transports it back to the cytoplasm, thereby terminating NF-κB-dependent transcription [62, 63]. Evidence further suggests that NF-κB-dependent transcription requires multiple coactivators (p300/CBP, P/CAF, and SRC-l/NcoA-1) possessing histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity [64–66]. NF-κB heterodimer p50/p65 can be acetylated at multiple lysine residues [67], which is believed to regulate the function of transcriptional activation, DNA-binding affinity, and IκBα affinity. These results suggest a link between acetylation events and NF-κB-mediated transactivation.

NF-κB IN OXIDATIVE STRESS

The oxidative stress induced under physiological and pathological conditions cause the injury by oxidation of lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Under physiological conditions, cells require sustained and inducible antioxidant defense mechanisms to counter the steady-state generation of ROS during normal cellular metabolism and acute oxidative challenges, respectively. Superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical, and H2O2 are constantly produced intracellularly as the side products of oxygen metabolism, and they are known to produce cellular oxidative damage and cause aging and carcinogenesis. ROS have been the focus of attention for many years in the research areas of free radical and radiation biology. Originally, ROS are recognized as being instrumental for mammalian host defense, as demonstrated by early works that led to the characterization of the respiratory burst of neutrophils and the NADPH oxidase complex, which is now recognized as a primary source of ROS. It is now generally accepted that NF-κB is a redox sensitive transcription factor and its activity can be regulated by the production of ROS induced by oxidants [68, 69]. Oxidative stress including exposure to lipid peroxidation products or depletion of reduced glutathione causes rapid phosphorylation and ubiquitination with subsequent degradation of the IκB complex, a critical step for NF-κB activation [70, 71]. Activated NF-κB subsequently regulates the expression of many genes, including mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme manganese-containing superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), involved in a specific stress, inflammatory response, cellular proliferation and transformation [72, 73]. These results indicate that NF-κB-mediated MnSOD activation through oxidative stress may have a profound effect on the adaptive resistance to anticancer agents [74].

NF-κB IN ADAPTIVE RADIORESISTANCE

Tumor radioresistance remains a critical obstacle to successful radiotherapy and/or radio-chemotherapy. Significant resistance to radiation and/or chemotherapeutic agents has been observed in several tumor or transformed cells [5–8]. Different doses of IR are shown to induce an adaptive resistance that is defined to be the reduced cell sensitivity to a higher challenging dose of a stressor when a smaller inducing dose had been applied a few hours earlier [9]. The molecular mechanism underlying IR-induced adaptive resistance, presumably via DNA repair and inhibition of apoptosis, has not been fully elucidated. To further increase the efficacy of radiotherapy, the molecules responsible for tumor resistance to a therapeutic dose range of IR needs to be elucidated. It is generally believed that the balance in DNA damage and repair decides the fate of an irradiated cell [75–79]. Irradiated cells have been shown to be able to increase their survival by reducing or repairing IR-induced damage via activation of stress responsive genes [9, 80–84]. This adaptive radioresistance is evidenced by the fact that pre-exposure to a low or mediate dose of IR (e.g., diagnosis X-ray) reduces the radiation toxicity and decreases the genomic instability caused by a subsequent high dose IR [77, 85–90]. Significant adaptive responses have been observed in cells treated with fractionated ionizing radiation (FIR) in vitro [6, 91]. Such adaptive radiation resistance in mammalian cells is believed to be associated with the induction of multidrug resistance-associated protein [92] and epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) [93, 94].

Blocking radiation-induced NF-κB activation has been shown to increases apoptotic response and decreases growth and clonogenic survival of several human cancer cell lines [4, 5, 8]. Therefore, NF-κB-related signaling pathways may play a critical role in tumor response to radiotherapy. However, inhibition of NF-κB in HD-MyZ Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells did not affect radiosensitivity [95]. In the case of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells, inhibition of NF-κB by a dominant negative super-repressor IκB mutant adenoviral construct enhanced apoptosis in DU145 cells [96], but not in PC3 cells [95]. In addition, cellular sensitivity to the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α and chemotherapeutic agents was not increased by the inhibition of NF-κB in HPB, HCT116, MCF-7, and OVCAR-3 cells [97]. These results, together with the observations that NF-κB controls more than 150 effector genes, suggest that NF-κB-mediated radioresistance is a complex signaling network and cross-talking with key DNA damage sensor proteins may play a critical role in therapy-associated tumor resistance.

INVOLVEMENT OF ATM IN REGULATION OF NF-κB

Because NF-κB has been shown to be an essential radiation protective factor [98, 99], and acute radiosensitivity is a hallmark of the human genetic disorder ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) [100], it is logically hypothesized that ATM and NF-κB deficiencies result in increased radiation sensitivity. Like A-T patients, ATM-null mice are extremely sensitive to IR [26]. Similar hypersensitivity to a variety of DSB-inducing agents [101, 102], including the topoisomerase inhibitors etoposide [103] and camptothecin (CPT) [104], was observed in cultured cells isolated from A-T patients or ATM-deficient mice. It is not clear how the absence of ATM leads to the hypersensitivity to DSBs. It has been suggested that a subtle defect in DSB repair may underlie this increased sensitivity [105]. Another possibility is that a defect in the induction of anti-apoptotic genes responsive to NF-κB contributes to enhanced cell death of A-T cells in response to DSBs.

The mechanism by which IR-induced DSBs activate NF-κB is still not entirely clear. ATM, function as a member of the PI3K-like family of large proteins, appears to link NF-κB response to DSBs, since NF-κB activation by IR or DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor CPT is reduced or abolished in cells from individuals with A-T [106, 107]. The DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), another member of the PI3K-like family of protein kinases, has also been implicated in the activation of NF-κB following exposure to IR [108]. For instance, normal diploid cells derived from A-T patients do not exhibit constitutive activation of NF-κB [109]. Also, another study demonstrate that ATM is essential for activation of the entire NF-κB pathway by DSBs in both cultured human cells and mouse tissues, including IKK activation, IκB degradation, and induction of NF-κB DNA binding activity [110]. ATM is not required for activation of this pathway by proinflammatory stimuli, such as TNF, PMA, or LPS. However, opposite results, i.e., ATM-independent activations of NF-κB were reported by several investigators. Mira et al. reported that SV40 large T-transformed cells derived from a patient null for the ATM gene exhibited constitutive expression of NF-κB and that in those cells, inhibition of NF-κB by expression of a modified form of IκBα, (missing the first 45 NH2-terminal amino acids) led to correction of the radiosensitivity associated with the A-T phenotype [111]. Expression of this truncated form of IκBα was also able to restore regulated activation of NF-κB in response to IR, indicating that the loss of ATM function led to the activation of NF-κB, which somehow promoted sensitivity to radiation. The detailed molecular mechanisms, using the ATM knockout mice, by which ATM regulates NF-κB remain to be determined.

INTERACTION OF ATM WITH NF-κB IN ADAPTIVE RADIATION RESPONSE

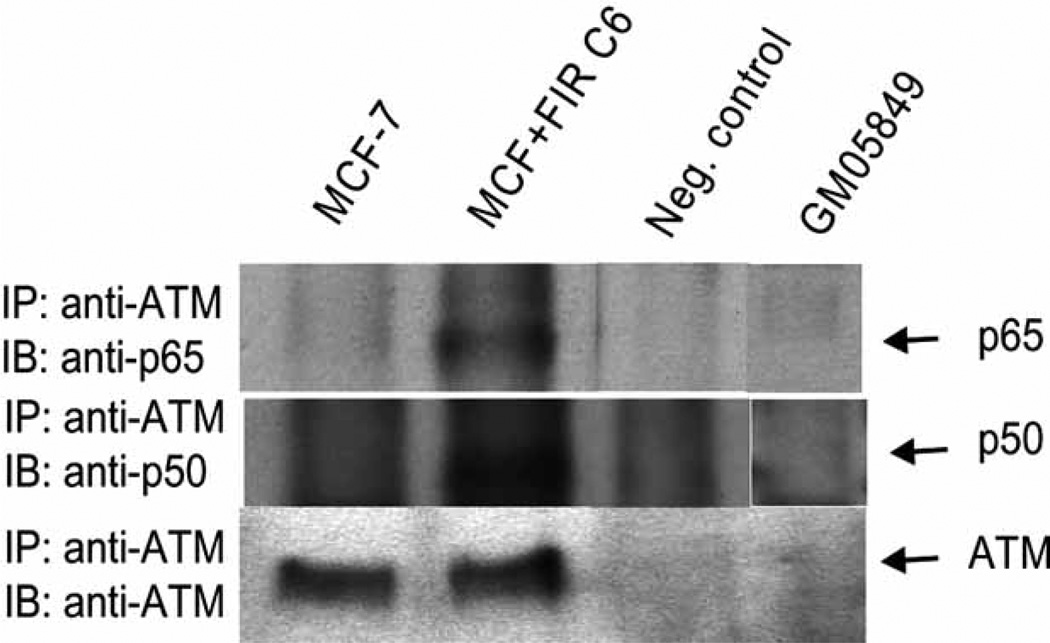

In a very recent study, Wu et al. proposed a model in which cytosolic signaling complex containing ATM, NEMO, IKK catalytic subunits, and ELKS is assembled in response to genotoxic stress to mediate NF-κB activation [112]. This model was based on the findings that (1) ELKS, a critical component of DNA damage-induced IKK activation, interacts with ATM upon genotoxic stress induction, and (2) ATM interacts with NEMO and phosphorylates Ser-85 of NEMO after the induction of DNA double-strand breaks. This event is required for mono-ubiquitination of NEMO, followed by nuclear export of NEMO and ATM and their subsequent interaction with the catalytic IKK subunit in the cytoplasm. Although Wu et al. and other investigators confirmed the connection of ATM in NF-κB activation, there is no report of a direct interaction between ATM and NF-κB family members in response to IR. Two recent studies from our laboratory clearly indicates the physical interaction between ATM and NF-κB p65 in response to adaptive radiation response in radioresistant breast cancer population (MCF+FIR) and immortalized human HK18 keratinocytes. Fig. 1 shows that ATM is co-immunoprecipitated with NF-κB p65 and p50 in radioresistant breast cancer MCF-7 cells (MCF+FIR C6) compared with the wild type MCF-7 and ATM-deficient GM05849 fibroblasts.

Fig. 1.

Cell extracts of MCF-7, MCF+FIR C6, and ATM-deficient GM05849 fibroblasts (as a negative control) were immunoprecipitated with an anti-ATM antibody and then blotted with p65, p50 or ATM antibody. For another negative control (Neg. control), immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) were performed without cell extracts [113].

The molecular mechanism by which tumor cells reduce their sensitivity to therapeutic radiation remains to be elucidated. As shown in Fig. 1 and Scheme 1, our current study on cell response to chronic IR stress (e.g., daily therapeutic exposure) indicates a direct interaction of ATM with NF-κB p65 and p50. NF-κB activity and protein levels were increased in radio-resistant breast cancer populations (MCF+FIR), derived from therapeutic doses of IR (total dose = 60 Gy of γ-irradiation; 2 Gy/day, 5 times/week for 6 weeks), but not in wild-type MCF-7 cells [113]. The level of pERK was remarkably inhibited in MCF+FIR cells with the increased NF-κB activity. These results indicate that ATM-regulated NF-κB plays an important role in the adaptive radiation resistance via inactivating the ERK signaling pathway. A reduction in the interaction and nuclear co-translocation of p65 and ERK was found in radioresistant MCF+FIR cells due to the increased interaction between p65 and MEK. In addition, ERK inhibitor PD98059 reduced p65/ERK interaction. Overall, these results provide the first evidence that cancer cells exposed to clinical therapeutic radiation may cause a selection of radioresistant clones, mediated by a novel signaling network of ATM/NF-κB/MEK/ERK, where ATM induces NF-κB activation that causes MEK/ERK inhibition. Therefore, targeting ATM-NF-κB connection with the activation of MEK/ERK pathway may provide a new approach to prevent therapy-associated tumor resistance.

As described above, the molecular mechanisms causing the adaptive response to IR by pre-exposure to low levels of radiation is poorly understood yet critical for adaptive protection against DNA damage and carcinogenesis. Scheme 2 shows the signaling network causing the adaptive resistance in immortalized human HK18 keratinocytes by LDIR (low dose ionizing radiation; 5–20 cGy of X-ray) (manuscript in preparation). Upon LDIR treatment, ATM is activated, which, in turn, activated NF-κB through the activation of an unknown kinase and MEK/ERK pathway. LDIR-induced ATM translocates to the nucleus, and NF-κB p65 interacts with ATM and 14-3-3ζ (an important mediator of altering protein localization), indicating that ATM-p65-14-3-3ζ complex may involve in nuclear translocation of ATM. However, ATM-NF-κB interaction was not observed in HK18/mIκB cells (NF-κB nuclear translocation is inhibited by dominant negative mutant of IκB), indicating that ATM-mediated NF-κB activation is crucial for the interaction. Activated NF-κB induces cell cycle regulatory proteins 14-3-3s (σ and ζ) and cyclins (D1 and B1). In addition, interaction of 14-3-3ζ with cyclin D1 was reduced greatly, and 14-3-3ζ-cyclin D1 complex remains in the cytoplasm after exposure to LDIR. Altogether, ATM-NF-κB connection plays an essential role in adaptive response to radiation, which may promise a new approach to protect normal tissue from radiation-induced injury.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the discovery of ATM and NF-κB, signaling networks involving both factors in IR-induced injury and repair has accumulated rapidly. Their primary function appears to help cells to deal with the genotoxic stress; especially DSBs. ATM is involved in cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair via protein phosphorylation of various substrates, including ATM itself. On the other hand, IR-activated NF-κB up-regulates many effector genes for a pro-survival signaling network. We have now provided the evidence suggesting that ATM and NF-κB are tightly linked, although there is still much to be learned about the regulatory mechanisms that operate in the cooperative ATM-NF-κB signaling pathway. These new results indicate a role of ATM-NF-κB complex in signaling the radioresistant phenotype of tumor cells. Thus, further investigation on ATM-NF-κB connection may promise a novel target to re-sensitize therapy-resistant tumors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the collaborators, postdoctoral fellows, and graduate students at the School of Health Sciences, Purdue University for their perceptive discussion and support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA101990), the Office of Science (BER), Department of Energy low dose radiation program (DE-FG02-05ER63945) and Purdue Cancer Center ELKS Research Award to J.J. Li.

ABBREVIATIONS

- A-T

Ataxia-telangiectasia

- ATM

Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- Chkl

Check point kinase 1

- Chk2

Check point kinase 2

- CPT

Camptothecin

- DNA-PK

DNA-dependent protein kinase

- DSB(s)

Double strand break(s)

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FIR

Fractionated ionizing radiation

- IκB

Inhibitor-kappaB

- IR

Ionizing radiation

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MnSOD

Manganese-containing superoxide dismutase

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappaB

- NIK

NF-κB-inducing kinase

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Redox

Oxidation/reduction reaction

- RHD

Rel homology domain

- ROIs

Reactive oxygen intermediates

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha;

REFERENCES

- 1.Shao R, Karunagaran D, Zhou BP, Li K, Lo SS, Deng J, Chiao P, Hung MC. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activity is involved in ElA-mediated sensitization of radiation-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(52):32739–32742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato T, Duffey DC, Ondrey FG, Dong G, Chen Z, Cook JA, Mitchell JB, Van Waes C. Cisplatin and radiation sensitivity in human head and neck squamous carcinomas are independently modulated by glutathione and transcription factor NF-kappaB. Head Neck. 2000;22(8):748–759. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<748::aid-hed2>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JP, Hori M, Takahashi N, Kawabe T, Kato H, Okamoto T. NF-kappaB subunit p65 binds to 53BP2 and inhibits cell death induced by 53BP2. Oncogene. 1999;18(37):5177–5186. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herscher LL, Cook JA, Pacelli R, Pass HI, Russo A, Mitchell JB. Principles of chemoradiation: theoretical and practical considerations. Oncology. 1999;13(10 Suppl 5):11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang G, Mmemoto Y, Dibling B, Purcell HN, Li Z, Karin M, Lin A. Inhibition of JNK activation through NF-kappaB target genes. Nature. 2001;414(6861):313–317. doi: 10.1038/35104568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell J, Wheldon TE, Stanton P. A radioresistant variant derived from a human neuroblastoma cell line is less prone to radiation-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1995;55(21):4915–4921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichholtz-Wirth H, Stoetzer O, Marx K. Reduced expression of the ICE-related protease CPP32 is associated with radiation-induced cisplatin resistance in HeLa cells. Br. J. Cancer. 1997;76(10):1322–1327. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Shen B, Xia L, Khaletzkiy A, Chu D, Wong JY, Li JJ. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in radioresistance of TP53-inactive human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2002;62(4):1213–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stecca C, Gerber GB. Adaptive response to DNA-damaging agents: a review of potential mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55(7):941–951. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Rotman G, Ziv Y, Vanagaite L, Tagle DA, Smith S, Uziel T, Sfez S, Ashkenazi M, Pecker I, Frydman M, Harnik R, Patanjali SR, Simmons A, Clines GA, Sartiel A, Gatti RA, Chessa L, Sandel O, Lavin MF, Jaspers NGJ, Taylor MR, Arlett CF, Sherman TM, Weissman SM, Lovett M, Collins FS, Shiloh T. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science. 1995;268(5218):1749–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.7792600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savitsky K, Sfez S, Tagle DA, Ziv Y, Sartiel A, Collins FS, Shiloh Y, Rotman G. The complete sequence of the coding region of the ATM gene reveals similarity to cell cycle regulators in different species. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4(11):2025–2032. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pecker I, Avraham KB, Gilbert DJ, Savitsky K, Rotman G, Harnik R, Fukao T, Schrock E, Hirotsune S, Tagle DA, Collins FS, Wynshaw-Boris A, Ried T, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. Identification and chromosomal localization of Atm, the mouse homolog of the ataxia-telangiectasia gene. Genomics. 1996;35(1):39–45. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chun HH, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(8–9):1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun X, Becker-Catania SG, Chun HH, Hwang MG, Huo Y, Wang Z, Mitui M, Sanal O, Chessa L, Crandall B, Gatti RA. Early diagnosis of ataxia-telangiectasia using radiosensitivity testing. J. Pediatr. 2002;140(6):724–731. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo YK, Wang Z, Hong JH, Chessa L, McBride WH, Perlman SL, Gatti RA. Radiosensitivity of ataxia-telangiectasia, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, and related syndromes using a modified colony survival assay. Cancer Res. 1994;54(10):2544–2547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor AM, Harnden DG, Arlett CF, Harcourt SA, Lehmann AR, Stevens S, Bridges BA. Ataxia telangiectasia: a human mutation with abnormal radiation sensitivity. Nature. 1975;258(5534):427–429. doi: 10.1038/258427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young BR, Painter RB. Radioresistant DNA synthesis and human genetic diseases. Hum. Genet. 1989;82(2):113–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00284040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen TJ, Shiloh Y. The ATM gene and the radiobiology of ataxia-telangiectasia. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1996;69(5):527–337. doi: 10.1080/095530096145535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhne M, Riballo E, Rief N, Rothkamm K, Jeggo PA, Lobrich M. A double-strand break repair defect in ATM-deficient cells contributes to radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2004;64(2):500–508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riballo E, Kuhne M, Rief N, Doherty A, Smith GG, Recio MJ, Reis C, Dahm K, Fricke A, Krempler A, Parker AR, Jackson SP, Gennery A, Jeggo PA, Lobrich M. A pathway of double-strand break rejoining dependent upon ATM, Artemis, and proteins locating to gamma-H2AX foci. Mol. Cell. 2004;16(5):715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecht F, Hecht BK. Cancer in ataxia-telangiectasia patients. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1990;46(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(90)90003-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274(5293):1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat. Genet. 2001;27(3):247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandita TK. A multifaceted role for ATM in genome maintenance. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2003;2003:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1462399403006318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3(3):155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlow C, Hirotsune S, Paylor R, Liyanage M, Eckhaus M, Collins F, Shiloh Y, Crawley JN, Ried T, Tagle D, Wynshaw-Boris A. Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1996;56(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown KD, Ziv Y, Sadanandan SN, Chessa L, Collins FS, Shiloh Y, Tagle DA. The ataxia-telangiectasia gene product, a constitutively expressed nuclear protein that is not up-regulated following genome damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94(5):1840–1845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandita TK, Lieberman HB, Lim DS, Dhar S, Zheng W, Taya T, Kastan MB. Ionizing radiation activates the ATM kinase throughout the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2000;19(11):1386–1391. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakin ND, Weber P, Stankovic T, Rottmghaus ST, Taylor AM, Jackson SP. Analysis of the ATM protein in wild-type and ataxia telangiectasia cells. Oncogene. 1996;13(12):2707–2716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirai Y, Hayashi T, Kubo Y, Hoki Y, Arita I, Tatsumi K, Seyama T. X-irradiation induces up-regulation of ATM gene expression in wild-type lymphoblastoid cell lines, but not in their heterozygous or homozygous ataxia-telangiectasia counterparts. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2001;92(6):710–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421(6922):499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Amours D, Jackson SP. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of dna repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3(5):317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Lim CU, Li JJ, Cai L, Zhang Y. The role of NBS1 in the modulation of PIKK family proteins ATM and ATR in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Lett. 2006 Mar;:9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.026. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Bosch M, Bree RT, Lowndes NF. The MRN complex: coordinating and mediating the response to broken chromosomes. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:844–849. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JH, Paull TT. Direct activation of the ATM protein kinase by the Mrell/Rad50/Nbsl complex. Science. 2004;304(5667):93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1091496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meulmeester E, Pereg Y, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG. ATM-mediated phosphorylations inhibit Mdmx/Mdm2 stabilization by HAUSP in favor of p53 activation. [Review] CellCycle. 2005;4(9):1166–1170. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traven A, Heierhorst J. SQ/TQ cluster domains: concentrated ATM/ATR kinase phosphorylation site regions in DNA-damage-response proteins. [Review] Bioessays. 2005;27(4):397–407. doi: 10.1002/bies.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGowan CH, Russell P. The DNA damage response: sensing and signaling. [Review] Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16(6):629–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huber A, Bai P, de Murcia JM, de Murcia G. PARP-1, PARP-2 and ATM in the DNA damage response: functional synergy in mouse development. [Review] DNA Repair. 2004;3(8–9):1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodarzi AA, Block WD, Lees-Miller SP. The role of ATM and ATR in DNA damage induced cell cycle control. [Review] Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:393–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khanna KK, Keating KE, Kozlov S, Scott S, Gatei M, Hobson K, Taya Y, Gabrielli B, Chan D, Lees-Miller SP, Lavin MF. ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction. Nat. Genet. 1998;20(4):398–400. doi: 10.1038/3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafman T, Khanna KK, Kedar P, Spring K, Kozlov S, Yen T, Hobson K, Gatei M, Zhang N, Watters D, Egerton M, Shiloh Y, Kharbanda S, Kufe D, Lavin MF. Interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1997;357(6632):520–523. doi: 10.1038/387520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foray N, Marot D, Randrianarison V, Venezia ND, Picard D, Perricaudet M, Favaudon V, Jeggo P. Constitutive association of BRCA1 and c-Abl and its ATM-dependent disruption after irradiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22(12):4020–4032. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4020-4032.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ward IM, Wu X, Chen J. Threonine 68 of Chk2 is phosphorylated at sites of DNA strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(51):47755–47758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iliakis G, Wang Y, Guan J, Wang H. DNA damage checkpoint control in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22(37):5834–5847. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma RS, Richman R, Wu Z, Piwnica-Worms H, Elledge SJ. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277(5331):1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng CY, Graves PR, Thoma RS, Wu Z, Shaw AW, Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277(5331):1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282(5395):1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suganuma M, Kawabe T, Hori H, Funabiki T, Okamoto T. Sensitization of cancer cells to DNA damage-induced cell death by specific cell cycle G2 checkpoint abrogation. Cancer Res. 1999;59(23):5887–5891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beamish H, Kedar P, Kaneko H, Chen P, Fukao T, Peng C, Beresten S, Gueven N, Purdie D, Lees-Miller S, Ellis N, Kondo N, Lavin MF. Functional link between BLM defective in Bloom’s syndrome and the ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated protein, ATM. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(34):30515–30523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sen R, Baltimore D. Inducibility of kappa immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein Nf-kappa B by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell. 1986;47:921–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nabel GJ, Verma IM. Proposed NF-kappa B/I kappa B family nomenclature. Genes Dev. 1993;7(11):2063. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuriyan J, Thanos D. Structure of the NF-kappa B transcription factor: a holistic interaction with DNA. Structure. 1995;3(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghosh G, van Duyne G, Ghosh S, Sigler PB. Structure of NF-kappa B p50 homodimer bound to a kappa B site. Nature. 1995;373(6512):303–310. doi: 10.1038/373303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracycline in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9(22):2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piette J, Piret B, Bomzzi G, Schoonbroodt S, Merville MP, Legrand-Poels S, Bours V. Multiple redox regulation in NF-kappaB transcription factor activation. Biol. Chem. 1997;375(11):1237–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen J-Y, Penco S, Ostrowski J, Balaguer P, Pons M, Starrett JE, Reczek P, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. RAR-specific agonist/antagonists which dissociate transactivation and AP1 transrepression inhibit anchorage-independent cell proliferation. EMBO J. 1995;14:1187–1197. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Traenckner EB, Pahl HL, Henkel T, Schmidt KN, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. Phosphorylation of human I kappa B-alpha on serines 32 and 36 controls I kappa B-alpha proteolysis and NF-kappa B activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 1995;14(12):2876–2883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baeuerle PA, Rupec RA, Pahl HL. Reactive oxygen intermediates as second messengers of a general pathogen response. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 1996;44(1):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ben-Neriah Y. Regulatory functions of ubiquitination in the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3(1):20–26. doi: 10.1038/ni0102-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl.):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gerritsen ME, Williams AJ, Neish AS, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94(7):2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Na SY, Lee SK, Han SJ, Choi HS, Im SY, Lee JW. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 interacts with the p50 subunit and coactivates nuclear factor kappaB-mediated transactivations. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(18):10831–10834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sheppard KA, Rose DW, Haque ZK, Kurokawa R, McInerney E, Westin S, Thanos D, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Collins T. Transcriptional activation by NF-kappaB requires multiple coactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19(9):6367–6378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen LF, Greene WC. Regulation of distinct biological activities of the NF-kappaB transcription factor complex by acetylation. J. Mol. Med. 2003;81(9):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman I, MacNee W. Role of transcription factors in inflammatory lung diseases. Thorax. 1998;53(7):601–612. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.7.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rahman I, MacNee W. Regulation of redox glutathione levels and gene transcription in lung inflammation: therapeutic approaches. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;25(9):1405–1420. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowie AG, Moynagh PN, O’Neill LA. Lipid peroxidation is involved in the activation of NF-kappaB by tumor necrosis factor but not interleukin-1 in the human endothelial cell line ECV304. Lack of involvement of H2O2 in NF-κB activation by either cytokine in both primary and transformed endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(41):25941–25950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ginn-Pease ME, Whisler RL. Optimal NF kappa B mediated transcriptional responses in Jurkat T cells exposed to oxidative stress are dependent on intracellular glutathione and costimulatory signals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;226(3):695–702. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, Heder A, Scheidereit C, Strauss M. NF-kappaB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19(4):2690–2698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finco TS, Westwick JK, Norris JL, Beg AA, Der CJ, Baldwin AS., Jr Oncogenic Ha-Ras-induced signaling activates NF-kappaB transcriptional activity which is required for cellular transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(39):24113–24116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang T, Zhang X, Li JJ. The role of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cell stress responses. Int. Immunopharmacol. 1994;2(11):1509–1520. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weichselbaum RR, Hallahan D, Fuks Z, Kufe D. Radiation induction of immediate early genes: effectors of the radiation-stress response. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. phys. 1994;30:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marty A, Kao GD, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG. Potential molecular targets for manipulating the radiation response. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. phys. 1997;37:639–653. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolff S. Are radiation-induced effects hormetic? Science. 1989;245(4918):621. doi: 10.1126/science.2762808. 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waldman T, Zhang Y, Dillehay L, Yu J, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Williams J. Cell-cycle arrest versus cell death in cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 1997;3:1034–1036. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Dent P, Grant S, Mikkelsen RB, Valerie K. Signal transduction and cellular radiation responses. Radiat. Res. 2000;153(3):245–257. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0245:stacrr]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolff S. The adaptive response in radiobiology: evolving insights and implications. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 1):277–283. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feinendegen LE. The role of adaptive responses following exposure to ionizing radiation. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1999;18(1):426–432. doi: 10.1191/096032799678840309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li Z, Xia L, Lee ML, Khaletskiy A, Wang J, Wong JYC, Li JJ. Effector genes altered in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells after exposure to fractionated ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res. 2001;155(4):543–553. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0543:egaimh]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feinendegen LE. Reactive oxygen species in cell responses to toxic agents. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002;21(2):85–90. doi: 10.1191/0960327102ht216oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guo G, Yan-Sanders Y, Lyn-Cook BD, Wang T, Tamae D, Ogi J, Khaletskiy A, Li Z, Weydert C, Longmate JA, Huang TT, Spitz DR, Oberley LW, Li JJ. Manganese superoxide dismutase-mediated gene expression in radiation-induced adaptive responses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23(7):2362–2378. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2362-2378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Olivieri G, Bodycote J, Wolff S. Adaptive response of human lymphocytes to low concentrations of radioactive thymidine. Science. 1984;223(4636):594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.6695170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Suppressive effect of low-dose preirradiation on genetic instability induced by X rays in normal human embryonic cells. Radia.t Res. 1998;150(6):656–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelsey KT, Memisoglu A, Frenkel D, Liber HL. Human lymphocytes exposed to low doses of X-rays are less susceptible to radiation-induced mutagenesis. Mutal Res. 1991;263(4):197–201. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(91)90001-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Skov KA. Perspectives on the adaptive response from studies on the response to low radiation doses (or to cisplatin) in mammalian cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1999;18(1):447–451. doi: 10.1191/096032799678840354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Robson T, Price ME, Moore ML, Joiner MC, McKelvey-Martin VJ, McKeown SR, Hirst DG. Increased repair and cell survival in cells treated with DIR1 antisense oligonucleotides: implications for induced radioresistance. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2000;76(5):617–623. doi: 10.1080/095530000138277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Extremely low-dose ionizing radiation causes activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and enhances proliferation of normal human diploid cells. Cancer Res. 2001;6i(14):5396–5401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill BT. Differing patterns of cross-resistance resulting from exposures to specific antitumour drugs or to radiation in vitro. Cytotechnology. 1993;72(1–3):265–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00744668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harvie RM, Davey MW, Davey R. Increased MRP expression is associated with resistance to radiation, anthracyclines and etoposide in cells treated with fractionated gamma-radiation. Int. J. Cancer. 1997;73(1):164–167. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<164::aid-ijc25>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Mikkelsen RB, Dent P, Todd DG, Valerie K, Kavanagh BD, Contessa JN, Rorrer WK, Chen PB. Radiation-induced proliferation of the human A431 squamous carcinoma cells is dependent on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. Oncogene. 1997;15(10):1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reardon DB, Contessa JN, Mikkelsen RB, Valerie K, Amir C, Dent P, Schmidt-Ullrich RK. Dominant negative EGFR-CD533 and inhibition of MAPK modify JNK1 activation and enhance radiation toxicity of human mammary carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1999;18(33):4756–4766. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pajonk F, Pajonk K, McBride WH. Inhibition of NF-kappaB, clonogenicity, and radiosensitivity of human cancer cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999;91(22):1956–1960. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Flynn V, Jr, Ramamtharan A, Moparty K, Davis R, Sikka S, Agrawal KC, Abdel-Mageed AB. Adenovirus-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB confers chemo-sensitization and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2003;23(2):317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bentires-Alj M, Hellin AC, Ameyar M, Chouaib S, Merville MP, Bours V. Stable inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB in cancer cells does not increase sensitivity to cytotoxic drugs. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274(5288):784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamagishi N, Miyakoshi J, Takebe H. Enhanced radiosensitivity by inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B activation in human malignant glioma cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1997;72(2):157–162. doi: 10.1080/095530097143374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lavin MF. Radiosensitivity and oxidative signalling in ataxia telangiectasia: an update. Radiother. Oncol. 1998;47(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McKinnon PJ. Ataxia-telangiectasia: an inherited disorder of ionizing-radiation sensitivity in man Progress in the elucidation of the underlying biochemical defect. Hum. Genet. 1987;75(3):197–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00281059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Westphal CH, Hoyes KP, Canman CE, Huang X, Kastan MB, Hendry JH, Leder P. Loss of atm radiosensitizes multiple p53 null tissues. Cancer Res. 1998;58(24):5637–5639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Caporossi D, Porfirio B, Nicoletti B, Palitti F, Degrassi F, De Salvia R, Tanzarella C. Hypersensitivity of lymphoblastoid lines derived from ataxia telangiectasia patients to the induction of chromosomal aberrations by etoposide (VP-16) Mutat Res. 1993;290(2):265–272. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90167-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Johnson RT, Gotoh E, Mullmger AM, Ryan AJ, Shiloh Y, Ziv Y, Squires S. Targeting double-strand breaks to replicating DNA identifies a subpathway of DSB repair that is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261(2):317–325. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jeggo PA, Carr AM, Lehmann AR. Splitting the ATM: distinct repair and checkpoint defects in ataxia-telangiectasia. Trends Genet. 1998;14(8):312–316. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee SJ, Dimtchev A, Lavin MF, Dritschilo A, Jung M. A novel ionizing radiation-induced signaling pathway that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 1998;17(14):1821–1826. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Piret B, Schoonbroodt S, Piette J. The ATM protein is required for sustained activation of NF-kappaB following DNA damage. Oncogene. 1999;18(13):2261–2271. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Basu S, Rosenzweig KR, Youmell M, Price BD. The DNA-dependent protein kinase participates in the activation of NF kappa B following DNA damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;247(1):79–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ashburner BP, Shackelford RE, Baldwin AS, Jr, Paules RS. Lack of involvement of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) in regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) in human diploid fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1999;59(21):5456–5460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li N, Banin S, Ouyang H, Li GC, Courtois G, Shiloh Y, Karin M, Rotman G. ATM is required for IkappaB kinase (IKKk) activation in response to DNA double strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(12):8898–8903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jung M, Zhang Y, Lee S, Dritschilo A. Correction of radiation sensitivity in ataxia telangiectasia cells by a truncated I kappa B-alpha. Science. 1995;265(5217):1619–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.7777860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wu ZH, Shi Y, Tibbetts RS, Miyamoto S. Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-kappaB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science. 2006;311(5164):1141–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1121513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ahmed KM, Dong S, Fan M, Li JJ. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in radioresistant breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;4(12):945–955. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]