Abstract

Erlotinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In these patients, erlotinib prolongs survival but its benefit remains modest since many tumors express wild-type (wt) epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or develop a second-site EGFR mutation. To test drug combinations that could improve the efficacy of erlotinib, we combined erlotinib with quinacrine, which inhibits the FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription) complex that is required for NF-κB transcriptional activity. In A549 (wtEGFR), H1975 (EGFR-L858R/T790M) and H1993 (MET amplification) NSCLC cells, this drug combination was highly synergistic, as quantified by Chou-Talalay combination indices, and slowed xenograft tumor growth. At a sub-IC50 but more clinically attainable concentration of erlotinib, quinacrine, alone or in combination with erlotinib, significantly inhibited colony formation and induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Quinacrine decreased the level of active FACT subunit SSRP1 and suppressed NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity. Knockdown of SSRP1 decreased cell growth and sensitized cells to erlotinib. Moreover, transcriptomic profiling showed that quinacrine or combination treatment significantly affected cell cycle-related genes that contain binding sites for transcription factors that regulate SSRP1 target genes. As potential biomarkers of drug combination efficacy, we identified genes that were more strongly suppressed by the combination than by either single treatment, and whose increased expression predicted poorer survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients. This preclinical study shows that quinacrine overcomes erlotinib resistance by inhibiting FACT and cell cycle progression, and supports a clinical trial testing erlotinib alone versus this combination in advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: Gene Expression Profiling, Lung Cancer, FACT, NF-κB, EGFR-TKI

Introduction

Metastatic NSCLC is the most common cause of cancer death in the United States. Cytotoxic chemotherapy has historically been the mainstay of therapy but is associated with only modest improvements in patient survival. Over the past decade, a better understanding of the pathogenesis of NSCLC, coupled with high throughput genomic technologies applied to patient tumor samples, has led to a molecular classification of NSCLC (and a new generation of “precision” therapies). This paradigm is best illustrated by the identification of activating mutations in EGFR as drivers of lung cancer development and progression and the subsequent demonstration of the clinical benefit of anti-EGFR therapies such as erlotinib (Tarceva), a reversible TKI of EGFR (1). On the other hand, the clinical benefit of erlotinib is modest in patients with wtEGFR, particularly in those with concurrent KRAS mutations (2, 3); in addition, even in the initially sensitive EGFR-mut+ patients, population resistance invariably develops through the development of second-site EGFR mutations, e.g., T790M (4), activation of alternative receptor tyrosine kinases, e.g., MET amplification (5), and other mechanisms including transformation from non-small cell to small cell histology (6).

Quinacrine was widely used during World War II as an antimalarial agent. Over the last four decades it has been used for the treatment of giardiasis, tapeworm infestations and connective tissue diseases, e.g., lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (7, 8). Recently, a chemical screen identified 9-aminoacridines, including quinacrine, as activators of p53 and inhibitors of NF-κB (9, 10). NF-κB regulates the expression of genes encoding pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic proteins. In contrast to the situation in normal cells, it is usually constitutively active in tumor cells and plays a key role in promoting tumorigenesis, including resistance to many cancer therapies (11–13). Indeed, a recent report showed that inhibition of NF-κB sensitizes NSCLC cells to erlotinib-induced cell death (14). Thus, NF-κB is an attractive target for cancer therapy (12, 15).

Quinacrine is thought to act by intercalating into DNA through its planar acridine ring, while its diaminobutyl side chain extends into the DNA minor groove (8). Recently, it was reported that quinacrine and its derivatives suppress NF-κB by causing chromatin trapping of the FACT complex (10), a heterodimer of the structure-specific recognition protein (SSRP1) and suppressor of Ty 16 (SPT16). The normal function of FACT is to promote reorganization of nucleosomes in front of RNA polymerase II during transcription elongation. However, FACT is often expressed in aggressive, undifferentiated cancers, and neoplastic (but not normal) cell growth depends on FACT activity (16). Chromatin trapping of FACT results in increased phosphorylation of p53 by the FACT-associated kinase CK2, and reduced NF-κB-dependent transcription because of the depletion of free active FACT (10).

To improve the clinical benefit of erlotinib in the treatment of advanced NSCLC, we investigated whether combination with quinacrine potentiates the ability of erlotinib to mediate cell death, and the mechanism underlying the observed synergistic effect in NSCLC cells. As a result of our findings, we are conducting a phase I/II clinical trial to test the combination of erlotinib and quinacrine in advanced or metastatic (stage IIIB/IV) NSCLC patients who have failed at least one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen (NCT01839955).

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Erlotinib was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (# S1023) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Quinacrine, from Sigma Aldrich (# Q3251), was dissolved in PBS as a 10 mM stock solution. Dilutions to the required concentrations were made in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) or RPMI-1640 medium. Mouse monoclonal SSRP1 antibody (# 609701) was from BioLegend. Rabbit polyclonal PARP antibody (# 9542) was from Cell Signaling. Mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (# A5316) was from Sigma. Goat polyclonal Lamin B (# sc-6216) and mouse monoclonal GAPDH antibody (# sc-32233) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell culture

The human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549, H1975 and H1993 were obtained from ATCC and passaged for fewer than 6 months following receipt or resuscitation from frozen stocks, and were maintained in DMEM (A549 and H1975) or RPMI-1640 (H1993) medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. All cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. A549 has wtEGFR and mutant KRAS (G61H), H1975 has the activating EGFRL858R mutation as well as the second site EGFRT790M mutation, which decreases the affinity of the receptor for erlotinib, and H1993 has wtEGFR and MET amplification.

Cell proliferation

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 1–2 × 103 per well, allowed to attach overnight, and treated with various concentrations of erlotinib, quinacrine, or a combination of both in a 5:1 or 10:1 molar ratio. After 72 h, cell viability was determined by the MTT assay (17). The combination index (CI) was assessed by using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO) (18, 19).

Clonogenic assay

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 500 per well, allowed to attach overnight, and treated with erlotinib, quinacrine or the combination in triplicate. Drugs were replaced every 72 h. After 14 days, cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet. Colonies were quantified using the cell counter plugin of the NIH ImageJ software (v.1.48).

Cell-cycle analysis

Cells were treated with 1 µM erlotinib, 3 µM or 5 µM quinacrine or a combination of both for 96 h or 120 h, and then fixed with 100% cold ethanol at −20°C for 1 h, and stained with 3 µM propidium iodide (PI) (Invitrogen, #P3566) in the presence of RNase for 15 min at room temperature. Cell cycle distribution was assessed by FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) analysis.

Analysis of apoptosis

Staining was performed using Annexin V-APC (eBioscience, #88-8007) in conjunction with PI according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and was assessed by FACScan. Apoptosis was validated by PARP cleavage, analyzed by the Western method.

NF-κB luciferase assay

A549 or H1975 cells were infected with the κB-luciferase lentiviral construct pLA-NFκB-mCMV-luc-H4-puro (or hygro) and stably selected with puromycin or hygromycin. This NF-κB reporter lentiviral vector consists of a firefly luciferase reporter gene under the control of a minimal (m)CMV promoter and six NF-κB-responsive elements from the immunoglobulin light chain gene (20) (kind gift from Dr. Peter Chumakov, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia). The reporter cells were then seeded in 96-well plates at 1–2 × 103 per well, allowed to attach overnight, and then treated with drugs and/or interleukin-1. Cells were then harvested in reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and assayed for luciferase activity using the luciferase assay system (Promega).

DNA binding assay

The ability of compounds to alter the mobility of plasmid DNA was tested by incubating plasmid DNA in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) with 10 µM quinacrine or chloroquine at room temperature for 20 min followed by electrophoresis (1% agarose gel, 1.5 V/cm constant for 16 hours). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/ml) and visualized with short-wavelength UV light.

shRNA-mediated knockdown

Lentiviral plasmids encoding shRNAs targeting GFP or SSRP1 (TRCN0000019270, “#2”; TRCN0000019272, “#4”) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Viruses were packaged in HEK 293T cells using the second-generation packaging constructs pCMV-dR8.74 and pMD2G (a kind gift from Dr. Mark Jackson, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA). Supernatant media containing virus were collected after 48 h and supplemented with 1 µg/ml polybrene before being used to infect cells for 6 h. Knockdown efficiency was evaluated by the Western method 48 h after infection.

Protein extraction and Western analysis

Soluble protein fractions were prepared by incubating cell pellets with occasional vortexing in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40 with protease inhibitors and then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min, discarding the crude nuclear pellet. Chromatin fractions were extracted according to Gasparian, et al (10). Briefly, after removal of soluble cytoplasmic fraction, chromatin-bound protein from the insoluble nuclear pellets were extracted with using a high salt lysis buffer containing 2 M NaCl followed by sonication (3 × 15 s, 30 s off). Cell extracts containing equal quantities of proteins, determined by the Bradford method, were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Rockland), using enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin-Elmer). Densitometry quantification of immunoblots was performed using the NIH-ImageJ software (v. 1.48).

Total RNA extraction and microarray analysis

RNA was isolated from cells treated with 1 µM erlotinib, 3 µM or 5 µM quinacrine or a combination of both for 6, 12, 24, or 48 h using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (48 h treatment samples were available only for erlotinib or combination treatment). Microarray analysis was performed using the Affymetrix Human Gene 2.1 ST Array at the Gene Expression & Genotyping Core Facility at Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Raw CEL files were pre-processed using the Affymetrix Expression Console Software 1.30 with Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) normalization (background correction, quantile normalization and log2 transformation). Probes were annotated using the HuGene 2.1 st hg19 probeset annotation files downloaded from the Affymetrix website. Low intensity probes (probes whose log2 expression levels in the untreated sample were less than the median expression level across all probes) were filtered out. Hierarchical clustering (average linkage method with Euclidean distance metrics) and principal component analysis was performed using Cluster 3.0 and visualized with the Java TreeView or JMP 10 software (SAS Institute). Differential gene expression analysis among treatment groups was performed using Bayesian Analysis of Variance for Microarrays (BAMarray) 3.0 (21), and the resulting gene lists were further narrowed down using STEM v. 1.3.8 (Short Time-series Expression Miner) (22) into genes whose expression showed greater than 2 fold changes compared to 0 h and significant temporal profiles. DAVID v6.7 (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) was used to analyze gene ontology processes for genes that were significantly affected by erlotinib-quinacrine combination treatment (23). Differentially regulated genes were analyzed for over-represented transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) compared to the background gene set using oPOSSUM 3.0. A z-score (rate of occurrence of a TFBS in target gene set vs background set) greater than mean+SD and a fisher score (proportion of genes in target gene set containing a TFBS vs that in background set) greater than 75% percentile were used as the cut-off to determine significant over-representation of TFBS (24). The Kaplan Meier-plotter [cancer survival analysis] (www.kmplot.com) was used to assess the effect of gene expression on lung cancer survival by downloading the Kaplan-Meier curves, hazard ratios and logrank P values of gene expression and survival data with relevant Affymetrix probe IDs (25).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Archive cDNA was prepared using the ABI High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., ABI) using 1 µg total RNA for each sample as starting material in a 100 µL reverse transcription reaction in an ABI 9700 Sequence Detection System. 384-well plates were set up to accommodate triplicate reactions for all assays. An endogenous control assay was used to control for RNA loading and to produce the normalized signal. TaqMan Assays for genes of interest (selected genes suppressed significantly by combination treatment from the microarray analysis) were purchased from ABI. Spectral data, gathered during the PCR run, were converted into numerical data using ABI SDS (sequence detection system) 2.3 proprietary software. All real-time RT-PCR reactions were performed at the Gene Expression Array Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Relative quantification of gene expression changes were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method, where ΔCt value = [Ct (gene of interest) − Ct (Endogenous Control)], and ΔΔCt = [ΔCt (treated) − ΔCt (untreated at 0h)].

Tumorigenicity assay

NCr nu/nu athymic nude mice were obtained from Taconic (Hudson, NY). Studies were conducted under an approved IACUC protocol by the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Athymic Animal and Xenograft Core. A549 cells were suspended at a density of 2 × 106 cells in 100 µL DMEM medium containing 5% FBS. Cell suspensions were subcutaneously injected into the rear flanks bilaterally of 6-week-old male mice (n = 5, 10 tumors per group). Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated with the formula 0.525 × W2 × L, where W and L were the smallest and largest diameters of the tumor in mm, measured every other day. Tumors were grown to at least 200 mm3 before start of treatment. Tumors that failed to engraft (reach double digit diameter) were excluded from the study. Thereafter, mice received daily oral gavage of vehicle control (0.5% w/v methyl cellulose), erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d), quinacrine (100 mg/kg loading dose at day one followed by 50 mg/kg/d), or combination of erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d) plus quinacrine (100 mg/kg initial dose followed by 50 mg/kg/d). Mice were sacrificed when tumors reached 17 mm in diameter.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses (except microarray data) were conducted using Graphpad Prism 5. Results are represented by means ± SD. Statistical significance was assumed for a 2-tailed P value less than 0.05 using ANOVA with the Bonferoni or Dunnett’s post-hoc test, compared to untreated controls or non-targeted shRNA.

Accession number

Microarray data in the form of raw CEL and RMA normalized matrix files were deposited on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession number GSE57422.

Results

The combination of erlotinib and quinacrine is synergistic in several NSCLC lung adenocarcinoma cell lines and inhibits in vivo NSCLC tumor cell growth

Constitutive NF-κB activation is known to mediate survival and drug resistance in cancer, and its inhibition has been reported to increase sensitivity to cancer therapies including EGFR-TKIs (12, 14). To test whether inhibition of NF-κB is synergistic with erlotinib, a major EGFR-TKI used in NSCLC treatment, we tested the effects of the combination of erlotinib and quinacrine, an NF-κB inhibitor, on cell viability in three NSCLC cell lines: A549 (wtEGFR, mutant KRAS), H1975 (EGFRL858R/T790M), and H1993 (MET amplification). Each of these cell lines harbor genetic aberrations that represent three major mechanisms driving resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in advanced NSCLC.

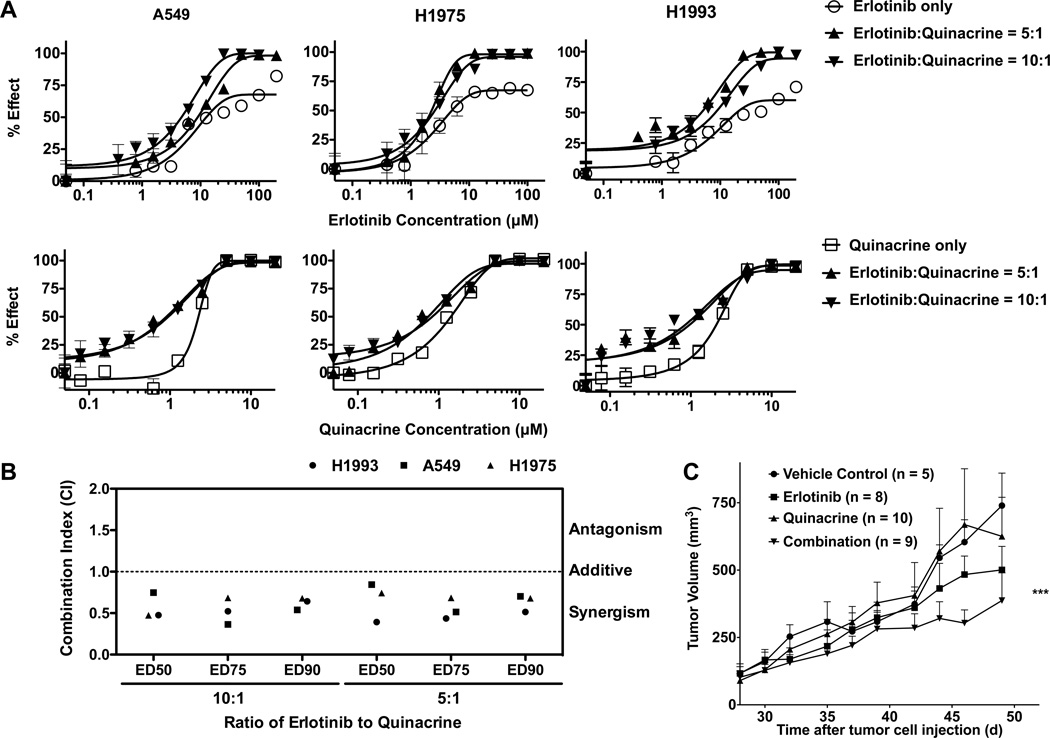

We first determined the individual IC50 values (half maximal inhibitory concentrations) for erlotinib and quinacrine in each cell line, which are between 5–12 µM and 1–2 µM, respectively. Based on their IC50 ratios, we combined erlotinib with quinacrine at a 5 to 1 or 10 to 1 ratio and measured cell viability after treatment. We then quantified the degrees of synergism using the median-drug effect analysis method developed by Chou and Talalay (18, 19). This method quantifies the combination indices (CI) of two drugs based on the growth inhibition curves of each drug alone or their combination (Fig 1A). The combination of erlotinib and quinacrine was synergistic in A549, H1975, and H1993 cells when combined at both 5:1 or 10:1 ratios [Effective Dose (ED)50: 0.61 (0.42–0.81); ED75: 0.53 (0.40–0.67); ED90: 0.63 (0.54–0.71)] (Fig 1B).

Figure 1.

The combination of erlotinib and quinacrine is synergistic in several NSCLC lung adenocarcinoma cell lines and inhibits in vivo xenograft tumor growth. A, A549 (wtEGFR), H1975 (EGFR-L858R/T790M) and H1993 (MET amplification) cells were treated with erlotinib, quinacrine, or the combination of both agents at a 5:1 or 10:1 molar ratio. After 72 h, cell viability was determined by the MTT assay (effect% = 100% − cell viability%). The experiments were repeated 3 times. B, The combination index (CI) was assessed using CalcuSyn software to determine drug interaction (additivity, synergism). A CI < 1.0 is considered to be synergistic. All values represent means ± SD. C. Growth curves of A549 lung adenocarcinoma xenograft in NCr nu/nu athymic mice. Following an initial growth period of 35 days, group tumor volume reached at least 200 mm3 prior to treatment (P = 0.5273 between groups). Tumor diameters were measured every other day. Treatment continued for at least 20 days before the mice were sacrificed. *** represents significance of P < 0.001 compared with vehicle control or quinacrine only treatment (ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test).

To determine the in vivo effect of this drug combination, we measured tumor growth in an A549 xenograft model treated with oral gavage of vehicle (0.5% methyl cellulose), erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d), and quinacrine (50 mg/kg/d with a 2-fold initial loading dose), or a combination of erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d) plus quinacrine (50 mg/kg/d with a 2-fold initial loading dose). The combination significantly inhibited in vivo tumor growth compared to vehicle control or single drug administration of quinacrine (Fig 1C).

The combination of quinacrine with erlotinib induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest

We treated A549 or H1975 cells with 1 µM erlotinib and either 5 µM or 3 µM quinacrine in most of the subsequent experiments. The sub-IC50 concentration of erlotinib was chosen because at the standard dosage of erlotinib (150 mg/d) used in the clinical setting, the maximum concentration of elrotinib (Cmax) achievable in humans is much lower than the IC50 of erlotinib in these resistant cell lines (26, 27). On the other hand, the Cmax of quinacrine reaches 3–5 µM in patients (unpublished data), and quinacrine is known to accumulate at high concentrations in tissues (especially in liver and lung) with a volume of distribution of approximately 50,000 L (7), and thus these concentrations were chosen because they could be achieved in vivo.

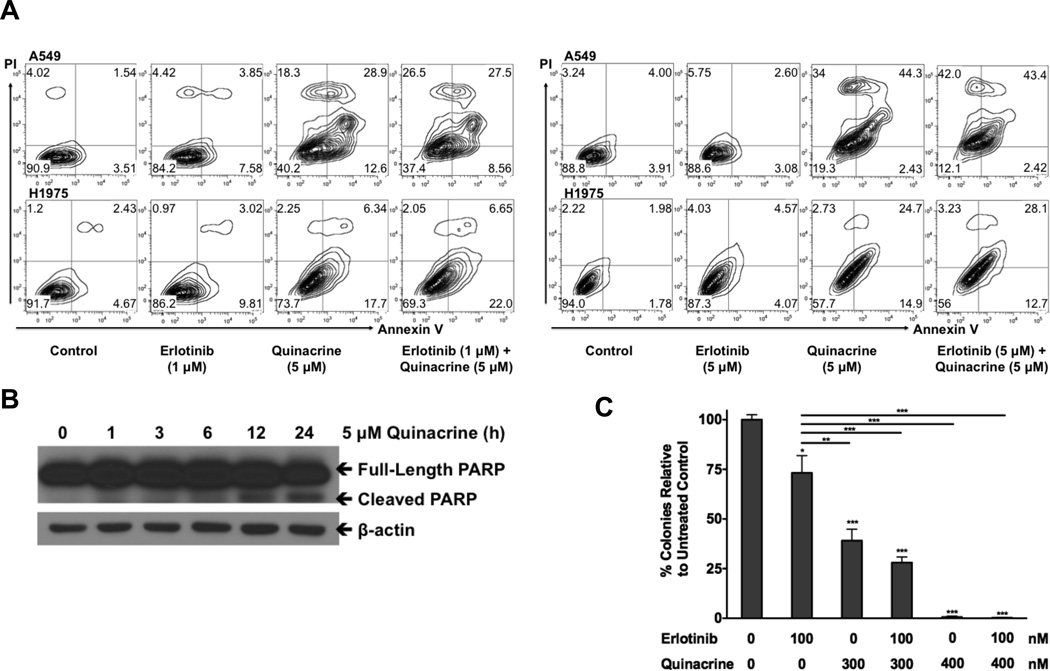

Since the combination shows synergy when erlotinib and quinacrine are used at their IC50 ratios (erlotinib:quinacrine = 5:1 or 10:1), at a concentration of 1 µM erlotinib and a concentration of 3–5 µM quinacrine in our erlotinib-resistant cell lines, the two drugs were no longer synergistic and quinacrine showed potent single-agent activity in this combination. Quinacrine alone or addition of quinacrine to erlotinib induced similar levels of cell death, as demonstrated by increased Annexin V-PI staining in A549 and H1975 cells after 48 h of treatment (Fig 2A), and when we increased erltoinib to 5 µM (which is still below its IC50), combination treatment induced higher levels of cell death than quinacrine alone (Fig 2A). We further confirmed this result by observing a time-dependent increase in PARP cleavage induced by quinacrine (Fig 2B). Quinacrine alone or addition of quinacrine to erlotinib treatment also significantly inhibited in vitro cell proliferation, as measured by colony formation (Fig 2C).

Figure 2.

The combination of quinacrine with erlotinib induced in vitro NSCLC cell apoptosis and inhibited cell growth. A, A549 and H1975 cells were untreated or treated with 1 µM (left panel) or 5 µM (right panel) erlotinib, 5 µM quinacrine, or both for 48 h. Apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V-PI double staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. B, H1975 cells were treated with 5 µM quinacrine for the indicated time-points. Western analysis was used to detect PARP cleavage as an indicator of apoptosis. C, A549 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with erlotinib, quinacrine, or a combination of both in triplicate at the indicated concentrations. Drugs were replaced every 72 h. After 14 days, colonies were stained and quantified. Statistical analysis of the differences in colony formation between the treated cells and untreated controls were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test (* P<0.05; *** P<0.001). All values represent means ± SD.

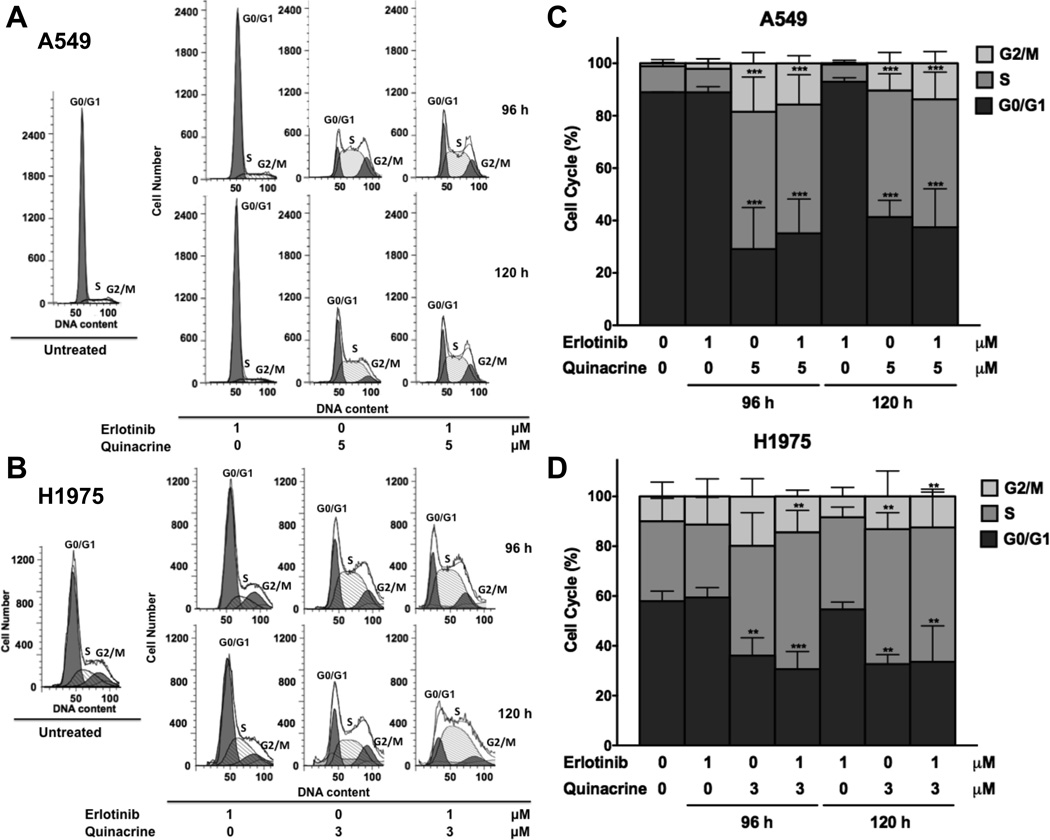

Next, we measured the effect of quinacrine plus erlotinib on cell cycle progression, using flow cytometry. Both quinacrine alone and combination treatment induced similar levels of marked G1/S and G2/M cell cycle arrest in A549 and H1975 cells. This effect was dominated by the action of quinacrine when the low concentration of 1 µM erlotinib was used (Fig 3A–D).

Figure 3.

The combination of quinacrine and erlotinib inhibits G1/S and G2/M cell cycle progression. A549 (A and C) and H1975 (B and D) cells were untreated or treated with erlotinib only, quinacrine only, or erlotinib plus quinacrine for 72 h or 96 h at the indicated concentrations. Cell cycle analysis was then performed using PI-staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. G1/S and G2/M cell cycle arrest was determined by quantifying relative G0/G1, S, and G2/M phase percentages. Statistical analysis of the differences in relative cell cycle phase percentages between the treated cells and untreated controls were conducted using two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (*** P<0.001). The experiment was repeated 3 times. All values represent means ± SD.

Quinacrine but not chloroquine suppresses NF-κB-driven luciferase activity

Next, we analyzed how quinacrine overcomes erlotinib resistance in NSCLC cells. Since the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways are known to be important for cell survival and are determinants of EGFR-TKI sensitivity in EGFR-driven cancers (28), we analyzed AKT and ERK phosphorylation in cells treated with either erlotinib or quinacrine, finding that only erlotinib inhibited AKT or ERK activation (data not shown). This result suggests that the effect of quinacrine on cell surivival is mediated through a pathway other than the PI3K/AKT or MAPK pathway.

A recent report suggested that chloroquine can overcome erlotinib resistance in NSCLC cells overexpressing wtEGFR by inhibiting autophagy (29). Both chloroquine and quinacrine are known to inhibit autophagy (30), but whether both of these anti-malarial drugs inhibit NF-κB remains uncertain. To address this issue, we determined whether quinacrine or chloroquine inhibits NF-κB activity in A549 or H1975, utilizing an NF-κB-luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase expression driven by either constitutively active NF-κB (Fig 4A) or interleukin-1 treatment (Fig 4B) were significantly suppressed by quinacrine but not by equal concentrations of chloroquine.

Figure 4.

Quinacrine but not chloroquine suppresses NF-κB-driven luciferase activity, mediates cell killing, and overcomes resistance to erlotinib by targeting FACT. A, Luciferase units relative to untreated control (RLU) were quantified in A549 or H1975 cells stably expressing NF-κB luciferase reporter after 4 h of treatment with increasing concentrations of quinacrine or chloroquine in triplicate. Statistical analysis of the differences in RLU between cells treated with different drug concentrations and untreated controls were conducted using two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (*** P<0.001). B, RLU was quantified in A549 or H1975 stable NF-κB luciferase reporter cells pretreated with 10 µM quinacrine or 10 µM chloroquine for 1h, and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml interleukin-1β for 6 h in quadruplicate. Statistical analysis of the differences in RLU between IL-1-treated or -untreated cells were conducted using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni Post Test (*** P<0.001). All values represent means ± SD. C, A549 or H1975 cells were treated with quinacrine or chloroquine for 1 h at the indicated concentrations. Soluble protein fractions were then extracted by mild cell lysis and the SSRP1 subunit of the FACT complex was analyzed by the Western method. D, A549 or H1975 cells were treated with 20 µM quinacrine for 3 h. The levels of SSRP1 in the cytoplasmic and chromatin fractions were analyzed by the Western method and quantified by densitometry. β-actin or lamin B served as loading controls. E, H1975 cells were transduced with shRNA lentiviruses against GFP or SSRP1. Cells were plated in quadruplicate and cell viability was measured by MTT assay 5 days post infection. F, A549 cells were infected with shRNA against GFP or SSRP1. Cells were plated in 6-well plates in triplicate and cell colonies were quantified after 2 weeks by crystal violet staining. H1975 (G) or A549 (H) cells were transiently infected with shSSRP1 and plated in 96-well plates and treated with DMSO or increasing concentrations of erlotinib over 72 h in quadruplicate. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Statistical analyses of the differences in cell viability or colony formation between SSRP1 or GFP knockdown cells were conducted using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (** P<0.01; *** P<0.001). All values represent means ± SD.

Quinacrine mediates cell killing and overcomes resistance to erlotinib by targeting FACT

Gasparian et al showed that a series of anticancer compounds including quinacrine suppress NF-κB activation by causing chromatin trapping of the FACT complex (10). This finding is supported by our observation that treatment of A549 or H1975 cells with quinacrine but not chloroquine rapidly depletes SSRP1, a FACT subunit, from the soluble cytoplasmic fraction (Fig 4C,D), and led to SSRP1 accumulation in the insoluble chromatin fraction (Fig 4D), which has also been shown by Gasparian et al to be an indicator of chromatin trapping of FACT (10). Since the overall level of SSRP1 from whole cell lysates remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig S1A), the decrease of SSRP1 from the cytoplasmic fraction was not due to protein degradation. Quinacrine and chloroquine are structurally related compounds known to interact with DNA, but with different affinities, due to the stronger drug-DNA ring-ring stacking interaction with quinacrine, which has a 3-ring acridine moiety, compared to chloroquine, which has a 2-ring quinolone moiety (Supplementary Fig S1B) (31), as shown by the ability of quinacrine but not chloroquine to reduce mobility of plasmid DNA (Supplementary Fig S1C). To test whether the anticancer activity of quinacrine in NSCLC is due to inhibition of FACT, we knocked SSRP1 down in A549 or H1975 cells. Loss of SSRP1 significantly decreased cell survival (Fig 4E,F) and increased sensitivity to erlotinib (Fig 4G,H) in both cell lines.

The quinacrine and erlotinib combination inhibits the expression of SSRP1-regulated genes and cell cycle genes that predict worse survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients

To further elucidate the mechanisms of the effect of combined quinacrine and erlotinib treatment in NSCLC, we performed global transcriptomic profiling of A549 and H1975 cells treated with 1 µM erlotinib alone, 5 or 3 µM quinacrine alone, or combinations of 1 µM erlotinib and 5 or 3 µM quinacrine for 0, 6, 12, or 24 h, using an Affymetrix microarray platform. (48 h treatment samples were available for erlotinib alone or combination treatment). Principal component analysis revealed that, relative to untreated cells at 0 h, gene expression profiles diverged most significantly with increased treatment time (24 h and 48 h) and with quinacrine or combination treatment (Supplementary Fig S2). We next determined genes that were differentially expressed between treatment groups. Differential gene expression analysis was used to identify genes that were significantly induced or suppressed by combination treatment compared to either single drug treatment and whose expression levels showed a > 2-fold change relative to 0 h and significant temporal profiles (Fig 5A,B). Gene ontology analysis showed that genes significantly affected by the combination were most highly enriched for those encoding proteins involved in cell cycle progression or DNA metabolism (Table 1), confirming our functional analysis showing that quinacrine plus erlotinib induced significant cell cycle arrest and inhibited tumor growth.

Figure 5.

Quinacrine and erlotinib combination treatment inhibits SSRP1-regulated genes and cell cycle genes whose increased expression predicts poorer survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients. A549 (upper panel) or H1975 (lower panel) cells were treated with or without erlotinib, quinacrine or combination for 6, 12, or 24 h. Differential gene expression analysis was used to identify genes that were significantly induced or suppressed by combination treatment compared to single drug treatment and showed a > 2-fold change relative to 0 h and significant temporal profiles, as represented by Venn diagrams (A) and hierarchical clustering (B). C, As potential biomarkers of drug combination efficacy in the ongoing clinical trial, cell cycle-related genes that showed significant temporal suppression by combination treatment compared to either single treatment alone in A549 cells were identified and represented in a heat map. D, Examples of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of lung adenocarcinoma patients from Supplementary Table 2 with high vs low KIFC1, FOSL1, BIRC5 or HIST1H2BM expression.

Table 1.

Gene ontology processes for genes that are significantly affected by erlotinib-quinacrine combination treatment

| A549 cells | ||

| GO Term | P-Value | |

| GO:0022402 | cell cycle process | 2.20E-18 |

| GO:0022403 | cell cycle phase | 2.37E-16 |

| GO:0000087 | M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 3.66E-16 |

| GO:0000279 | M phase | 2.55E-15 |

| GO:0000278 | mitotic cell cycle | 1.31E-14 |

| GO:0000280 | nuclear division | 2.25E-14 |

| GO:0007067 | mitosis | 2.46E-14 |

| GO:0048285 | organelle fission | 2.46E-14 |

| GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | 1.20E-13 |

| GO:0006974 | response to DNA damage stimulus | 1.44E-12 |

| GO:0006281 | DNA repair | 3.63E-11 |

| GO:0051301 | cell division | 1.02E-10 |

| GO:0033554 | cellular response to stress | 1.21E-09 |

| GO:0007059 | chromosome segregation | 4.58E-09 |

| H1975 cells | ||

| GO Term | P-Value | |

| GO:0010558 | negative regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process | 0.0065 |

| GO:0006281 | DNA repair | 0.012 |

| GO:0006350 | transcription | 0.018 |

| GO:0007219 | Notch signaling pathway | 0.020 |

| GO:0010605 | negative regulation of macromolecule metabolic process | 0.021 |

| GO:0016481 | negative regulation of transcription | 0.021 |

| GO:0051252 | regulation of RNA metabolic process | 0.022 |

| GO:0009219 | pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide metabolic process | 0.0228 |

| GO:0010629 | negative regulation of gene expression | 0.024 |

| GO:0051052 | regulation of DNA metabolic process | 0.026 |

Next, we analyzed the enrichment of transcription factor binding sites among those genes whose expression was significantly affected by quinacrine or by erlotinib plus quinacrine. Comparison of our data with the ChIP-SEQ results for SSRP1-enriched genes reported by Garcia et al (16) showed that many of the genes affected by quinacrine or combination treatment were regulated by the same transcription factors that were also involved in regulating expression of SSRP1-enriched genes. These transcription factors belong to the EGR (EGR1), ETS (ELK1, ELK4, GABPA, SPI1), MYC (MYC, MYCN) and SP/KLF (SP1, KLF4) families (Supplementary Table 1). This result supports our observation that quinacrine targets and inhibits the FACT complex (16). Interestingly, the levels of the FACT subunit SSRP1 and SPT16 mRNAs were not affected by drug treatment in our microarray study (data not shown), which corroborates previous reports showing that the action of quinacrine on FACT is at a functional level, by trapping the FACT complex onto chromatin.

To identify potential biomarkers for erlotinib-quinacrine synergy, we identified genes that were suppressed more significantly by combination treatment than by either drug alone in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells (Fig 5C). The more potent suppression of this gene set by combination treatment was verified by Taqman-based quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig S3). Since our functional analysis showed that the combination of erlotinib and quinacrine induced significant cell cycle arrest, we preferentially selected genes that our gene ontology analysis showed to be involved in cell cycle progression. Importantly, increased expression of these genes was associated with poorer survival in NSCLC patients (HR ranges from 1.19–1.98), and this correlation was even more significant when only lung adenocarcinoma patients were analyzed (HR ranges from 1.58–2.92) (Supplementary Table 2, Fig 5D). This result is relevant to an ongoing phase I/II clinical trial (NCT01839955) to test the combination of erlotinib and quinacrine in metastatic (stage IIIB–IV) NSCLC patients who failed first-line chemotherapy, the vast majority of whom have wtEGFR non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma tumors. Therefore, our preclinical studies for this clinical trial not only identify a potential set of treatment response pharmacodynamic biomarkers, but also suggest important biological mechanisms regulating the potent single-agent activity of quinacrine activity in erlotinib-insensitive NSCLC patients.

Discussion

Erlotinib is effective in NSCLC patients with known drug-sensitizing EGFR mutations (3), but its clinical efficacy in patients with wtEGFR or acquired resistance to TKIs due to secondary mutations remains modest (3, 6). We show here that the addition of quinacrine to erlotinb in several patient-derived erlotinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines overcomes resistance to erlotinib. A major advantage of our strategy is the pairing of a highly specific small molecule kinase inhibitor, erlotinib, to a broadly acting DNA intercalator, quinacrine, thereby decreasing the chance of emergence of resistance against targeted therapies.

Quinacrine has been shown to reduces the availability of the FACT complex by causing its trapping on chromatin (10), and FACT was shown by the same group to promote tumor survival and growth (16). Since the ability of quinacrine to inhibit FACT and subsequently modulate NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activity is not dependent on direct binding to these targets but is mediated by binding to DNA (10), it may be less likely for drug resistance to arise. Even though quinacrine intercalates into DNA, it is not genotoxic (10), and its side effects and general toxicity, which have been well-documented over several decades due to its extensive use in the prevention and treatment of malaria and other parasitic diseases, are well-tolerated (7, 8). A future experiment looking at whether overexpression of FACT itself could overcome resistance to erlotinib or other EGFR-TKI in NSCLC would be valuable.

We are currently conducting a phase I/II clinical trial (NCT01839955) to test erlotinib alone versus erlotinib plus quinacrine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic (stage IIIB/IV) NSCLC with either: 1) wtEGFR, with disease progression after previous platinum-based chemotherapy, for which erlotinib was approved as a second-line monotherapy; or 2) documented EGFRL858R/T790M mutation or EML4-ALK fusion gene, with subsequent progression on first-line erlotinib or crizotinib and chemotherapy. Using the Chou-Talalay method, we determined the two drugs to be synergistic at their respective IC50 ratios in erlotinib-resistant cell lines, when erlotinib was used at a much higher concentration (5:1 or 10:1) than quinacrine. However, based on preexisting pharmacokinetics data, in these erlotinib-resistant patients, erlotinib is likely to reach only a sub-IC50 serum concentration (26, 27) while quinacrine is known to accumulate in tissues (7). When we selected drug doses more representative of those achievable clinically, we observed potent single-agent activity of quinacrine in the erlotinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines. At such concentrations, quinacrine dominates the cell killing activity of the combination, as indicated by our colony formation, cell cycle and apoptosis assay, and our drug synergy quantification predicts that a much higher erlotinib concentration would be needed to achieve synergy with quinacrine in these assays. This result suggests that the inclusion of quinacrine alone as one of the arms in a future clinical trial would be valuable. Our findings also indicate that observation of drug synergy in in vitro studies might fail to translate to clinical trials when the same ratios are not attainable based on in vivo drug pharmacokinetics.

We also identified, as potential pharmacodynamic markers for this clinical trial, a set of genes whose expression levels were significantly suppressed by combination therapy and were shown to correlate with worse patient survival in existing gene expression databases. Since these are post-treatment rather than pre-treatment biomarkers, the goal is to use these gene signatures to validate that the biological efficacy of the combination over single drug treatment during the early phase of treatment by gene expression profiling of pre- and post-treatment biopsies from the subjects in our clinical trial, and then apply this knowledge to select for patients who would truly benefit from the combination and thus would remain in the trial through the entire course of treatment. For future studies, to identify pre-treatment predictive pharmacodynamics biomarkers, we would need to identify cell lines that are resistant to the combination and compare their gene signatures with those of cell lines that are sensitive to the combination, such as those used in the present study.

Recent discoveries of the high degree of intra-tumoral and inter-metastatic genetic heterogeneity among tumor cells in cancer genomics projects suggest that the development of resistance is inevitable in any targeted therapy for cancer (32). The use of combinatorial therapy is an important means to circumvent this problem since the probability of cancer cells becoming resistant to two independent pathways is exponentially smaller than the probability of resistance to a single agent. Our novel combination offers a promising therapy in advanced NSCLC, for which there are currently few effective treatment options after the tumors have progressed during first-line anticancer treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Martina Veigl and Patrick Leahy at the Gene Expression Array Core Facility for their valuable input in the design and analysis of the microarray study, Vai Pathak for conducting the ABI Expression Realtime RT-PCR experiments, Ian Lent at the Translational Research & Pharmacology Core Facility for performing the CalcuSyn analysis, and Cathy Shemo and Bunny Cotleur at the CCF Flow Cytometry Core for excellent technical support for flow cytometry data acquisiton and analysis.

Financial support. This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant P01 CA062220 to G.R. Stark. Clinical & Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland Core Utilization pilot grant P30 CA043703-23 at Case Western Reserve University to N. Sharma, and a Harrington Discovery Institute grant to G. Narla.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, Farina G, Veronese S, Rulli E, et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and wild-type EGFR tumors (TAILOR): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:981–988. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues PJ, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehsanian R, Van Waes C, Feller SM. Beyond DNA binding – a review of the potential mechanisms mediating quinacrine’s therapeutic activities in parasitic infections, inflammation, and cancers. Cell Commun Signal. 2011;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurova K. New hopes from old drugs: revisiting DNA-binding small molecules as anticancer agents. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1685–1704. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurova KV, Hill JE, Guo C, Prokvolit A, Burdelya LG, Samoylova E, et al. Small molecules that reactivate p53 in renal cell carcinoma reveal a NF-κB-dependent mechanism of p53 suppression in tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17448–17453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508888102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasparian AV, Burkhart CA, Purmal AA, Brodsky L, Pal M, Saranadasa M, et al. Curaxins: anticancer compounds that simultaneously suppress NF-κB and activate p53 by targeting FACT. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:1–12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu T, Sathe SS, Swiatkowski SM, Hampole CV, Stark GR. Secretion of cytokines and growth factors as a general cause of constitutive NFκB activation in cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:2138–2145. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi C, Toi M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka K, Babic I, Nathanson D, Akhavan D, Guo D, Gini B, et al. Oncogenic EGFR signaling activates an mTORC2-NF-κB pathway that promotes chemotherapy resistance. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:524–538. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bivona TG, Hieronymus H, Parker J, Chang K, Taron M, Rosell R, et al. FAS and NF-κB signaling modulate dependence of lung cancers on mutant EGFR. Nature. 2011;471:523–526. doi: 10.1038/nature09870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown M, Cohen J, Arun P, Chen Z, Van Waes C. NF-κB in carcinoma therapy and prevention. Exp Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:1109–1122. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.9.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia H, Miecznikowski JC, Safina A, Commane M, Ruusulehto A, Kilpinen S, et al. Facilitates Chromatin Transcription Complex is an “accelerator” of tumor transformation and potential marker and target of aggressive cancers. Cell Rep. 2013;4:159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Meerloo J, Kaspers GJ, Cloos J. Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;731:237–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-080-5_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010:440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasparian AV, Guryanova OA, Chebotaev DV, Shishkin AA, Yemelyanov AY, Budunova IV. Targeting transcription factor NFκB: comparative analysis of proteasome and IKK inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1559–1566. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishwaran H, Rao JS, Kogalur UB. BAMarray: Java software for Bayesian analysis of variance for microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernst J, Bar-Joseph Z. STEM: a tool for analysis of short time series gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman BT, Huang DW, Lempicki RA. Systemic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho Sui SJ, Mortimer JR, Arenillas DJ, Brumm J, Walsh CJ, Kennedy BP, et al. oPOSSUM: identification of over-represented transcription factor binding sites in co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acid Res. 2005;33:3154–3164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Győrffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lánczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidalgo M, Siu LL, Neumunaitis J, Rizzo J, Hammond LA, Takimoto C, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of OSI-774, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3267–3279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu JF, Eppler SM, Wolf J, Hamilton M, Rakhit A, Bruno R, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of erlotinib in patients with solid tumors and exposure-safety relationship in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou Y, Ling YH, Sironi J, Schwartz EL, Perez-Soler R, Piperdi B. The autophagy inhibitor chloroquine overcomes the innate resistance of wild-type EGFR non-small-cell-lung cancer cells to erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:693–702. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828c7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimmelman AC. The dynamic nature of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1999–2010. doi: 10.1101/gad.17558811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolte J, Demuynck C, Lhomme MF, Lhomme J, Barbet J, Roques BP. Synthetic models related to DNA intercalating molecules: comparison between quinacrine and chloroquine in their ring-ring interaction with adenine and thymine. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:760–765. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garraway La, Lander ES. Lessons from the cancer genome. Cell. 2013;153:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.