Abstract

Children adopted from institutions have been studied as models of the impact of stimulus deprivation on cognitive development (Nelson et al., 2011), but these children may also suffer from micronutrient deficiencies (Fuglestad et al., 2008). The contributions of iron deficiency (ID) and duration of deprivation on cognitive functioning in children adopted from institutions between 17 and 36 months of age were examined. ID was assessed in 55 children soon after adoption, and cognitive functioning was evaluated 11–14.6 months post-adoption when the children averaged 37.4 months old (SD = 4.9). ID at adoption and longer duration of institutional care independently predicted lower IQ scores and executive function (EF) performance. IQ did not mediate the association between ID and EF.

Deprivation early in life has been associated with persisting cognitive, social, and physiological abnormalities in humans (Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm, & Schuder, 2001; Kreppner et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2011; Rutter et al., 2004; Rutter, Sonuga-Barke, & Castle, 2010). Children adopted from institutional (orphanage) care have been studied as models of the impact of stimulus deprivation on development as many fail to receive care that optimizes physical, cognitive, and social functioning (Nelson et al., 2011). Research suggests that disruptions early in life may interfere with the development of more general cognitive skills that are the foundation of higher-order cognitive processes so that an environmental deficit in early development is especially detrimental (Fox, Levitt, & Nelson, 2010).

Animal models have demonstrated the pervasive effects of early deprivation on brain and cognitive development. Rodent models have demonstrated that chronic deprivation leads to dendritic remodeling of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and these alterations are related to deficits in performance on attention tasks (Liston et al., 2006). Research in nonhuman primates supports the role of early deprivation in producing impaired cognitive abilities and altered neural circuitry of the PFC (Sánchez, Hearn, Do, Rilling, & Herndon, 1998; Sánchez, Ladd, & Plotsky, 2001).

As in the animal literature, children who experience early deprivation often show deficits in cognitive functioning. For example, post-institutionalized (PI) children have been shown to have lower IQ than non-adopted peers (Hostinar et al., 2012; Pollak et al., 2010). Even after controlling for IQ, PI children score lower on measures of executive function (EF), which includes higher-order cognitive skills such as planning and problem solving (Hostinar et al., 2012). Cognitive deficits in PI children are often correlated with the duration of institutionalization, with more time in institutions related to poorer performance on cognitive tasks (e.g., Colvert et al., 2008; Pollak et al., 2010).

For years, researchers have wondered whether it was nutritional deprivation rather than stimulus and emotional deprivation that caused the cognitive and behavioral anomalies reported in PI children (Rutter, 1972; Sonuga-Barke, Schlotz, & Rutter, 2010; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2008). To date, the examination of nutrition in PI children has largely been limited to the assessment of macronutrient status, generally utilizing weight for age or body mass index. For example, findings from the English and Romanian Adoptees study report that both duration of institutional deprivation and sub-nutrition, as indexed by weight at adoption, predicted lower IQ in children adopted from institutions (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2008). However, it is unclear which aspect(s) of nutrient deprivation are most highly associated with cognitive deficits in PI children, macronutrients or specific micronutrient deficiencies.

The next step is to consider specific micronutrients that are critical to brain development (Fuglestad, Rao, & Georgieff, 2008). Specifically, iron deficiency (ID) has been shown to impact striatal-frontal dopaminergic connections and produce functional deficits in attention, EF, and socioemotional development (for review, see Georgieff, 2011; Lozoff et al., 2006). In PI children, approximately 25% are iron deficient at adoption (Fuglestad et al., 2013; Fuglestad, Lehmann, et al., 2008). Micronutrient deficiencies, including ID, may be due to poor nutrition or the impact of pre- or postnatal stress on iron absorption. Poor nutrition and psychosocial stress often co-occur (Monk et al., 2013). Monk, Georgieff, and Osterholm (2013) recently proposed a “dual variable” approach to studying the effects of early life stress and nutrition on brain development in order to disentangle the associations between the two.

Iron Deficiency

ID has consistently been associated with lower mental and motor development scores and altered socioemotional behavior in infants (Lozoff et al., 2006). Young PI children who were iron deficient at adoption scored lower on cognitive measures six months post-adoption than iron sufficient PI children (Fuglestad et al., 2013). Even as adults, individuals who experienced chronic ID in infancy performed worse, particularly on measures of EF (Lukowski et al., 2010). ID is especially risky in early childhood since it may persist after adoption, even when children consume recommended levels of dietary iron (Fuglestad, Lehmann, et al., 2008). In particular, ID worsens directly in proportion to the amount of rapid post-adoption growth, putting the brain at further risk during the sensitive period of brain development in early childhood (Fuglestad, Lehmann, et al., 2008). Although iron supplementation eventually reverses ID, it does not prevent long-term cognitive delays that likely occur due to lack of iron during a sensitive period (Baker & Greer, 2010; Felt et al., 2006; Lozoff et al., 2006; Lozoff et al., 2008). There is some debate about whether these cognitive effects are due to confounding variables instead of iron, but extensive pre-clinical models provide convincing evidence that ID during sensitive periods of brain development is related to irreversible cognitive deficits (Lozoff et al., 2006) and that the effect is iron specific (ie, not due to anemia) (Fretham et al, 2011). Supplementation studies show a modest positive effect in certain human populations and certain time periods, and caution must be used when interpreting these interventional studies since factors such as baseline ID rate, the timing of treatment, the dose of iron relative to the degree of ID, and the selection of appropriate cognitive tests relative to timing of ID and stage of brain development may all affect the outcomes of the studies.

ID operates in a temporal and severity hierarchy in which certain biomarkers are associated with different stages of deficiency (Cook, 1982). The first stage of pre-anemic ID involves low ferritin levels, and the second stage is characterized by low iron saturation and elevated iron binding capacity (IBC). Third, the red blood cells decrease in size, reflected by low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) levels. All of these stages are considered “pre-anemic” ID, which is three times more common than ID anemia (IDA). The final stage of frank IDA is characterized by below normal levels of hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit and has well-established negative implications for brain development (Lozoff et al., 2006; Lozoff et al., 2008). A small number of studies in humans strongly suggest that pre-anemic ID has a negative effect on brain development (Lozoff et al., 2008). Thus, this study will investigate whether both pre-anemic and anemic ID in PI children predict cognitive functioning beyond the effect of institutional care duration.

This study is a reanalysis of data previously published by Hostinar et al. (2012) that found that longer duration of institutional care predicted IQ and EF scores 12 months post-adoption, and that IQ partially mediated the effects of institutional duration on EF. Here we examined whether ID would at least partially mediate the association between duration of institutional care and cognitive outcomes or whether ID might have an independent effect beyond the effect of duration of institutionalization. If ID mediates the relationship, then we would need to question whether effects associated with early institutional care might be more parsimoniously attributed to ID and perhaps other micronutrient deficiencies rather than stimulus deprivation. However, if both ID and institutional care have independent effects, they should be understood as separate risk factors for neurodevelopment that may affect different neural circuitry or have additive negative effects on similar circuitry.

Method

Participants

Participants included 55 internationally adopted children recruited from the Minnesota International Adoption Project Registry, the University of Minnesota International Adoption Clinic, adoption agencies, and newspaper and website articles. Children were recruited if they were adopted between 17–36 months of age (M = 25.0 mos., SD = 4.7 mos.) and had lived in an institution (orphanage or hospital) for at least 4 months prior to adoption (range: 4–34 mos., M = 17.5 mos., SD = 7.8 mos.). Over half of participants had lived in an institution at least 80% of their lives prior to adoption. Participants included 29 females and 26 males from Africa (16), Asia (22), Eastern Europe (12), and Latin America (5). These children were 18.4–36.1 mos. old at the time of the clinic visit (M = 25.7 mos., SD = 4.7), and the visit occurred 0–2 months after arrival (M = 0.7 mos., SD = 0.38). The cognitive assessment occurred 11.4–14.6 months after adoption (M = 12.4 mos., SD = 0.6) when the children were 29.4–48.6 mos. old (M = 37.4 mos., SD = 5.0).

Procedure

Children completed a medical visit 0–2 months after adoption. Parents completed a phone interview with an adoption expert soon after adoption in which they provided information about the duration of institutional care (time in months the child spent in an orphanage or hospital). Approximately 12 months after adoption, children completed an EF battery and IQ assessment.

Iron Deficiency

ID was assessed by serum samples taken at each child’s first medical visit after adoption, and clinics provided available information on hemoglobin, transferrin saturation (TS), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), ferritin, and iron-binding capacity (IBC). Abnormal values were defined as hemoglobin concentration < 110g/L, TS < 12%, MCV < 74 fl, ferritin < 12 µg/L, and IBC > 538 µg/dL (Lozoff et al., 2008; Fuglestad et al., 2013). The following includes the number of children with abnormal values: hemoglobin (11), TS (16), MCV (11), ferritin (11), and IBC (3). Children were grouped in order from highest to lowest severity of ID: IDA (low hemoglobin levels), pre-anemic ID with 2 or more abnormal indices (normal hemoglobin and at least 2 abnormal TS, MCV, ferritin, or IBC results), pre-anemic ID with 1 abnormal index, and normal iron status (normal results for all iron variables). In this study, 11 children were IDA, 5 were ID with 2 or more abnormal indices, 11 were ID with 1 abnormal index, and 28 children had normal iron status.

Anthropometric Assessments

Researchers collected height and weight from the first medical visit. Height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores were computed using World Health Organization guidelines. Both height-for-age (M = −1.17, SD = 1.15) and weight-for-age (M = −0.60, SD = 0.97) were below the mean, consistent with growth restriction. Growth data were not collected at 12 months, but growth was assessed approximately 8–9 months post-adoption (M = 8.34, SD = 0.60) that was used to calculate growth rate as a possible covariate. The rate of linear growth (in cm) and weight gain (in kg) per month were calculated by taking the difference between height or weight at the first medical visit and the 8–9 month assessment and dividing by the number of months between visits. Both linear growth rate (M = 0.77, SD = 0.30) and rate of weight gain (M = 0.27, SD = 0.16) indicate catch-up growth.

IQ Assessment

Cognitive development was evaluated between 11–14.6 months after adoption. IQ was assessed using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning, which assess visual reception, fine motor, receptive language, and expressive language abilities (Mullen, 1995). Scores were summed and converted to an age-scaled standardized IQ score, M = 100, SD = 15. The Mullen Scales have been validated using large samples and are highly correlated with other cognitive measures, including the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence and the Bayley Mental Development Index (Bradley-Johnson, 2001; Lichtenberger, 2005). Four children were unable to complete the IQ assessment (3 due to difficulties finishing the assessment and 1 due to parent refusal) and are only included in the EF analyses.

Executive Function Measures

The EF domains that were studied include inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. Inhibitory control was assessed using the delay of gratification task (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). The child was asked to choose a favorite food from a number of options and was then presented with two bowls: one containing 2 of the chosen treats and another containing 10 treats. The experimenter asked the child to choose which bowl he or she preferred, and the child almost always preferred the bowl with more treats. The experimenter then explained to the child that she needed to leave the room and would give the child the larger reward when she returned. However, the experimenter explained that the child could ring a bell to have her return to the room early but the child would only be given the smaller reward. A verbal rule check was administered, and then the experimenter left the room until either the child rang the bell, began eating the treat, or waited for 8 minutes. Video recordings were used to assess the latency to the first touch of the treat or bell and the time waited.

The graded scale of the Dimensional Change Card Sort (Beck, Schaefer, Pang, & Carlson, 2011) was used to measure cognitive flexibility. The following levels were administered in order of increasing difficulty: Categorization, Reverse Categorization, Separated Card Sorting, and Integrated Card Sorting. In Categorization, children were asked to sort toy “mommy” and “baby” animals into mommy and baby buckets labeled with pictures of the mother or baby. The experimenter administered two demonstration trials and a rule check before the children were instructed to sort on their own, with a score of 5 correct trials out of 6 total trials sufficient to pass the level. Reverse Categorization forced children to switch the rules by sorting the mommy animals into the baby bucket and the baby animals into the mommy bucket (minimum of 5 out of 6 trials correct to pass). During Separated Card Sorting, the child sat in front of two boxes with slits in the top, one of which had a target card with a black truck on a red background and the other had a black star on a blue background. The child was then presented with cards that had either a black truck on a blue background or a black star on a red background and were asked to play the “shape game” by sorting the cards into target boxes by shape. If the child obtained a minimum of 5 out of 6 trials correct, they moved onto the “color game” in which they were instructed to sort by color. Children had to pass both the shape and color games in order to pass the Separated Card Sorting level. Finally, Integrated Card Sorting required the children to switch between the shape and color games. The cards integrated both shape and color into the stimulus (e.g. blue star on a white background), and the passing criteria were the same as previous levels. Before every trial at each level, the experimenter repeated the rule to minimize working memory load. The final score on the task indicated the highest level passed (range: 0–4).

Working memory was assessed using the spin the pots task (Hughes & Ensor, 2005). Several uniquely decorated boxes were arranged on a circular table that could rotate, and the experimenter placed a sticker in all but two boxes in front of the child. Then the experimenter put a scarf over the boxes, rotated the table 180°, and had the child pick a box in order to find a sticker. If the child found a sticker, they could keep it, and then the scarf was replaced and the table rotated for another trial. The total number of trials and boxes differed by age: 2.5-year-olds had 8 boxes and 12 spins, 3-year-olds had 9 boxes and 14 spins, 3.5-year-olds had 10 boxes and 16 spins, and 4-year-olds had 11 boxes and 18 spins. The task ended when the child found all the stickers or used all of their spins. Children were given a 1 if they located all the stickers and a 0 if they did not.

In order to reduce the number of analyses, performance on each of the 3 EF tasks was converted to z-scores to be on the same scale and then averaged to create a single EF composite variable. Z-scores were calculated for latency to touch in delay of gratification, highest level passed on the DCCS, and finding all the stickers in spin the pots. Due to an error with the video recording system, latency to touch could not be assessed for 4 children and the remaining two z-scores were averaged to yield the EF composite score. The EF composite was correlated with IQ, but still showed unique variance, r(51) = 0.45, p = .001.

Data Analytic Plan

First, as height and weight at adoption may be a measure of macronutrient deprivation, correlations were computed for height-for-age and weight-for-age at the child’s first clinic visit to test whether either variable was related to IQ or EF in order to determine whether they needed to be included as covariates. The rate of weight gain and linear growth from the first medical visit to approximately 8 months post-adoption were also considered as covariates in this manner. Second, a correlational analysis was computed to identify overlap in the two hypothesized independent variables, ID and duration of institutionalization. If the two were correlated, a test of mediation would be conducted to determine whether ID would mediate the impact of institutional care on IQ and EF. A regression analysis was then used to examine whether ID and duration of institutionalization predicted IQ approximately 12 months post-adoption. ID was coded on an ordinal scale from 0–3 with normal iron status as the least severe and IDA as the most severe form of ID (normal iron= 0, pre-anemic ID with 1 abnormal index = 1, pre-anemic ID with 2+ abnormal indices = 2, IDA = 3). A linear regression controlling for age was conducted to analyze whether iron status influenced EF beyond the effect of duration of institutionalization. Age was controlled for as scores on EF tasks typically increase with age (Carlson, 2005). An additional regression analysis was conducted adding IQ as a covariate to determine whether ID and duration of institutional care predicted EF even after controlling for the effect of IQ. Finally, a test of mediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011) was then conducted to examine whether IQ mediated any association between ID and EF.

Results

Duration of institutionalization and ID were not correlated, r(55) = .03, ns. Therefore, ID does not mediate the effect of duration of institutionalization on IQ and EF. Height-for-age at adoption, weight-for-age at adoption, rate of linear growth, and rate of weight gain were not correlated with either IQ or EF, all r’s ≤ .20, df’s 51 or 55, ns. As a result, the growth variables were not included as covariates in the regression analyses. A single linear regression analysis was conducted to test whether ID predicted variance in IQ scores above the effect of institutional duration. Both longer duration of institutionalization, β= −0.36, F(1, 49) = −2.75, p < .01, and ID at adoption significantly predicted lower IQ scores, β = −0.27, F(1, 49) = −2.05, p < .05, and combined explained 19.4% of the variance (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of ID (iron deficiency) on IQ scores (standard scoring: M = 100, SD = 15). Means and standard errors for children in the normal iron, pre-anemic ID with 1 abnormal index, pre-anemic ID with 2+ abnormal indices, and IDA (ID anemia) groups are displayed.

Table 1.

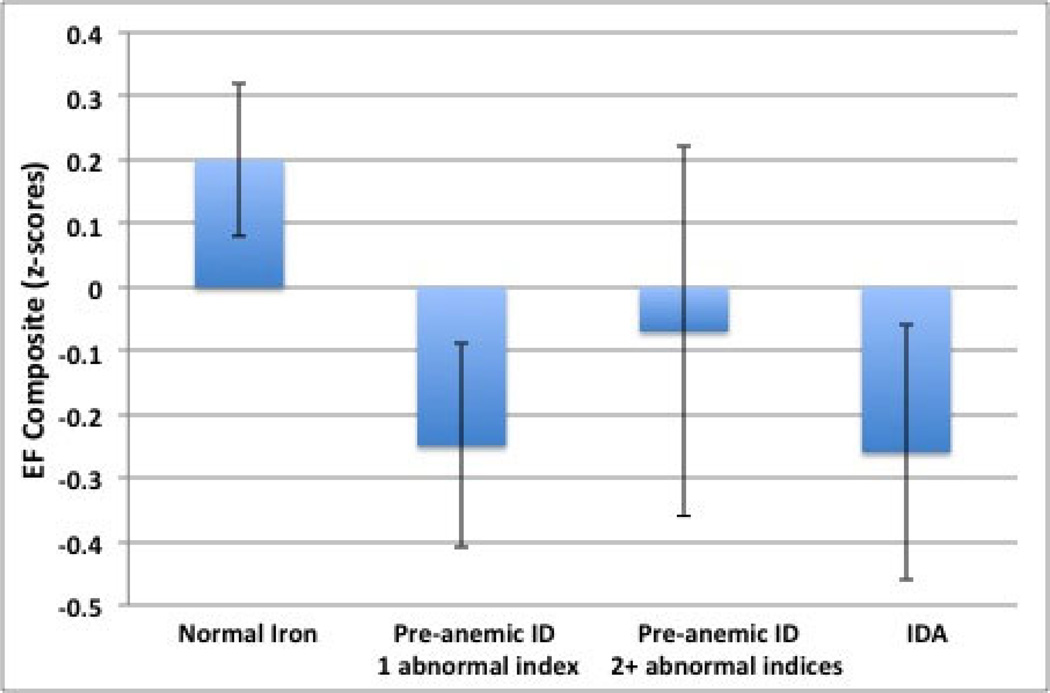

IQ and EF Means by Iron Severity Group

| Normal Iron | Pre-Anemic ID 1 Abnormal Index |

Pre-anemic ID 2+ Abnormal Indices |

IDA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

| IQ Score | 97.02 | 2.79 | 89.27 | 4.22 | 81.17 | 6.29 | 88.97 | 4.43 |

| EF Composite | 0.20 | 0.12 | −0.25 | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.29 | −0.26 | 0.20 |

Note: ID = iron deficiency, IDA = ID anemia, EF = executive function

Means and standard error of IQ (M = 100, SD = 15) and EF (executive function) composite (z-score) by iron group. IQ scores are reported controlling for the effect of duration of institutionalization, and EF scores are reported controlling for the effects of age and duration of institutional care.

Controlling for age, duration of institutional care significantly predicted lower scores on the EF composite, β = −.28, F(1, 53) = −2.18, p < .05, and ID at adoption predicted variance in EF scores above the effect of duration of institutionalization, β = −.26, F(1, 53) = −2.03, p < .05 (see Fig. 2). As the effect of ID and institutional care could impact global cognitive functioning rather than EF specifically, IQ was then added to the model as a covariate to test whether the effect of ID and institutional care would remain significant. This analysis revealed that IQ and EF shared sufficient variance that with IQ in the model neither ID or duration of institutional care predicted EF, F(1, 49) = −.58, p > .05, and F(1, 49) = −.61, p > .05, respectively (Table 2). On the other hand, a test of mediation conducted to examine whether IQ mediated the association between ID and EF was not significant as the 95% confidence interval included 0, [−.157, .002].

Figure 2.

The effect of ID (iron deficiency) on the EF composite (z-score). Means and standard errors for children in the normal iron, pre-anemic ID with 1 abnormal index, pre-anemic ID with 2+ abnormal indices, and IDA (ID anemia) groups are displayed.

Table 2.

EF Regression Results

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.30* | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.37** |

| Iron Status | −0.15 | 0.07 | −0.26* | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.08 |

| Duration of Inst. | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.28* | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 |

| IQ | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.50** | |||

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.34 | ||||

p < .05

p < .01.

EF = Executive function

Discussion

In this investigation, ID and duration of institutionalization independently predicted IQ and EF 12 months post-adoption. IDA, pre-anemic ID, and longer duration of institutionalization were associated with increasingly depressed measures of IQ. These findings suggest that ID does not help explain why institutional care is associated with lower IQ and EF scores, while still pointing to ID as another risk factor for poor cognitive outcomes in children adopted from institutional care. The relation between early ID and poorer cognitive functioning may have occurred through alterations in metabolic activity, neurotransmitter function, and myelination in the brain (Lozoff et al., 2006). Although biologically we might expect global effects on cognitive function, which is supported by the IQ results, it also appears that there are associations with EF beyond the effects on IQ and thus with the development of neural systems that support EF.

It is notable that the results of this study indicate that even less severe levels of ID may be associated with poorer cognitive functioning. The pre-anemic ID groups sort with the IDA group on cognitive measures with an effect size that has been demonstrated in previous studies (approximately 10 IQ points lower), in line with the literature on the negative effects of pre-anemic ID (e.g., Lozoff et al., 2008). There is evidence that brain iron content may be depleted before red blood cell iron content (Georgieff, Schmidt, Mills, Radmer, & Widness, 1992; Petry et al., 1992), so the pre-anemic children may already be experiencing the effects of low brain iron content. Thus, iron status should be carefully assessed at adoption, including the measurement of pre-anemic indicators of negative iron balance, so that children at risk can be targeted for iron supplementation or cognitive interventions that improve child outcomes. Even non-adopted children may benefit from careful monitoring of iron status in early childhood as ID significantly predicted cognitive outcomes independent of duration of institutionalization. Children in at-risk groups might particularly benefit from iron assessment, as findings in the adopted group may generalize to other groups experiencing early adversity.

There were limitations to the current study. First, we did not have enough children to be able to divide the PI children into distinct and well-characterized groups by deficiency in specific iron markers. Future research with larger samples will be needed to clarify at what stage of ID these changes in cognition are clinically significant. Second, there may have been other nutrient deficiencies (e.g., zinc, choline) that also affect cognitive function that were not measured in this study. Third, we only had measures of IQ and EF a year after adoption. Were the children to be followed, the influence of pre-adoption deprivation and iron status might change over time. Finally, ID was not assessed at the time of the cognitive assessment so it is unclear whether any further changes in iron status since adoption could have contributed to the findings. However, there is evidence that early ID has lasting impacts on cognitive development even after supplementation (Felt et al., 2006), and our results are consistent with ID predicting poorer cognitive functioning post-adoption.

Studies that examine the extent to which duration of institutionalization and ID at adoption continue to predict IQ and EF over time are greatly needed. Future studies should provide insight into the aspects of early deprivation that affect individuals across the lifespan and the ability of the brain to recover after stress (e.g., plasticity). As ID predicted IQ and EF above the effect of institutional duration, iron status should be evaluated to assess risk for poor cognitive outcomes and provide proper support for cognitive development in PI children. In this sample, nearly half of the children exhibited some level of ID, and our results indicate that even less severe ID is associated with cognitive deficits. Researchers studying children adopted from conditions of deprivation should not ignore the role that micronutrient deficiencies may be playing in these children’s development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating families as well as the members of the International Adoption Project at the University of Minnesota. This research was supported by Grants MH080905 and MH078105 (to Megan R. Gunnar), Grant R01HD051495 (to Stephanie M. Carlson), and, in part, by the Center for Neurobehavioral Development at the University of Minnesota. In addition, an NIMH training grant (T32MH015755, Dante Cicchetti, PI) supported Jenalee Doom.

References

- Baker RD, Greer FR Committee on Nutrition. Clinical report: diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 months of age) Pediatrics. 2010;126:1040–1050. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck DM, Schaefer C, Pang K, Carlson SM. Executive function in preschool children: Test-retest reliability. Journal of Cognitive Development. 2011;12:169–193. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2011.563485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley-Johnson S. Cognitive assessment for the youngest children: A critical review of tests. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2001;19:19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvert E, Rutter M, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, Sonuga-Barke E. Do theory of mind and executive function deficits underlie the adverse outcomes associated with profound early deprivation?: Findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1057–1068. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD. Clinical evaluation of iron deficiency. Seminars in Hematology. 1982;19:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felt BT, Beard JL, Schallert T, Shao J, Aldridge JW, Connor JR, Lozoff B. Persistent neurochemical and behavioral abnormalities in adulthood despite early iron supplementation for perinatal iron deficiency anemia in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;171:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development. 2010;81:28–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fretham SJB, Carlson ES, Wobken J, Tran PV, Petryk A, Georgieff MK. Temporal manipulation of transferrin receptor-1 dependent iron uptake identifies a sensitive period in mouse hippocampal neurodevelopment. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1691–1702. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglestad AJ, Georgieff MK, Iverson SL, Miller BS, Petryk A, Johnson DE, Kroupina MG. Iron deficiency after arrival is associated with general cognitive and behavioral impairment in post-institutionalized children adopted from Eastern Europe. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17:1080–1087. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1090-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglestad AJ, Lehmann AE, Kroupina MG, Petryk A, Miller BS, Iverson SL, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency in international adoptees from Eastern Europe. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;153:272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglestad A, Rao R, Georgieff MK. The role of nutrition in cognitive development. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Georgieff MK. Long-term brain and behavioral consequences of early iron deficiency. Nutrition Reviews. 2011;69:S43–S48. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieff MK, Schmidt RL, Mills MM, Radmer WJ, Widness JA. Fetal iron and cytochrome c status after intrauterine hypoxemia and erythropoietin administration. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:R485–R491. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.3.R485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Morison SJ, Chisholm K, Schuder M. Salivary cortisol levels in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:611–628. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100311x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostinar CE, Stellern SA, Schaefer C, Carlson SM, Gunnar MR. Associations between early life adversity and executive function in children adopted internationally from orphanages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:17208–17212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121246109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Ensor R. Executive function and theory of mind in 2 year olds: A family affair? Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:645–668. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner JM, Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, Colvert E, Groothues C, Sonuga-Barke E. Normality and impairment following profound early institutional deprivation: A longitudinal examination through childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:931–946. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberger EO. General measures of cognition for the preschool child. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Review. 2005;11:197–208. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston C, Miller MM, Goldwater DS, Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Hof PR, McEwen BS. Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7870–7874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Felt B, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutrition Reviews. 2006;64:S34–S91. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B, Clark KM, Jing Y, Armony-Sivan R, Angelilli ML, Jacobson SW. Dose-response relationships between iron deficiency with or without anemia and infant social-emotional behavior. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowski AF, Koss M, Burden MJ, Jonides J, Nelson CA, Kaciroti N, Lozoff B. Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive functioning at 19 years: evidence of long-term deficits in executive function and recognition memory. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2010;13:54–70. doi: 10.1179/147683010X12611460763689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI. Delay of gratification in children. Science. 1989;244:933–938. doi: 10.1126/science.2658056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Georgieff MK, Osterholm EA. Research review: Maternal prenatal distress and poor nutrition – mutually influencing risk factors affecting infant neurocognitive development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:115–130. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Bos K, Gunnar MR, Sonuga-Barke EJ. The neurobiological toll of early human deprivation. In: McCall R, editor. Children without permanent parental care: Research, practice, and policy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 127–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry CD, Eaton MA, Wobken JD, Mills MM, Johnson DE, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency of liver, heart, and brain in newborn infants of diabetic mothers. Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;121:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Schlaak M, Roeber B, Wewerka S, Wiik KL, Gunnar MR. Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in post-institutionalized children. Child Development. 2010;81:224–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Maternal deprivation reassessed. Penguin: Harmondsworth, Middlesex; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, O’Connor TG English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. Are There biological programming effects for psychological development? Findings from a study of Romanian adoptees. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:81–94. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Castle J. I. Investigating the impact of early institutional deprivation on development: Background and research strategy of the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2010;75:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez MM, Hearn EF, Do D, Rilling JK, Herndon JG. Differential rearing affects corpus callosum size and cognitive function of rhesus monkeys. Brain Research. 1998;812:38–49. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00857-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: Evidence from rodent and primate models. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:419–449. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003029. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Beckett C, Kreppner J, Castle J, Colvert E, Stevens S, Hawkins A, Rutter M. Is sub-nutrition necessary for a poor outcome following early institutional deprivation? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2008;50:664–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Schlotz W, Rutter M. VII. Physical growth and maturation following early severe institutional deprivation: Do they mediate specific psychopathological effects? Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2010;75:143–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]