Abstract

Eukaryotic cell division or cytokinesis has been a major target for anticancer drug discovery. After the huge success of paclitaxel and docetaxel, microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs) appear to have gained a premier status in the discovery of next-generation anticancer agents. However, the drug resistance caused by MDR, point mutations, and overexpression of tubulin subtypes, etc., is a serious issue associated with these agents. Accordingly, the discovery and development of new-generation MSAs that can obviate various drug resistances has a significant meaning. In sharp contrast, prokaryotic cell division has been largely unexploited for the discovery and development of antibacterial drugs. However, recent studies on the mechanism of bacterial cytokinesis revealed that the most abundant and highly conserved cell division protein, FtsZ, would be an excellent new target for the drug discovery of next-generation antibacterial agents that can circumvent drug-resistances to the commonly used drugs for tuberculosis, MRSA and other infections. This review describes an account of our research on these two fronts in drug discovery, targeting eukaryotic as well as prokaryotic cell division.

Keywords: Microtubule, Tubulin, FtsZ, Protofilament, Cytokinesis, Taxoid, Taxane, Benzimidazole, Anticancer agent, Antibacterial agent, Tuberculosis

1. Introduction

Microtubule/tubulin has been a major target for the discovery and development of anticancer drugs, i.e., “microtubule-interacting drugs” such as vinca alkaloids (vinblastine and vincristine) and taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel and cabazitaxel).1 Vinca alkaloids destabilize microtubules, while taxanes stabilize microtubules.1 After the great success of paclitaxel as an epoch-making anticancer drug, microtubule-stabilizing agents have gained substantial attentions for potential discovery of the next-generation drugs, e.g., epothilones, discodermolide, eleutherobin, laulimalide and zampanolide.2–4 We have been developing new-generation taxoids, which possess much higher potency than the first-generation taxanes, i.e., paclitaxel and docetaxel, particularly against drug-resistant cancer cell lines and tumor xenografts, wherein the drug resistance is caused by MDR, point mutation and β-tubulin subtypes (Figure 1).5–11 These new-generation taxoids interact with microtubules in a manner different from that of paclitaxel and docetaxel.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of representative new-generation taxoids discussed in this article.

In sharp contrast, cytokinesis remains largely unexploited for the discovery and development of antibacterial drugs. Filamentous temperature-sensitive protein Z (FtsZ), a tubulin homolog, is the most abundant and highly conserved cell division protein in bacteria. In the presence of GTP, FtsZ polymerizes bi-directionally at the center of the bacterial cell on the inner membrane to form a highly dynamic helical structure known as the “Z-ring”.12–16 The recruitment of several other cell division proteins leads to Z-ring contraction, resulting in septum formation and eventually cell division. We envisioned that (i) the disruption of Z-ring formation, either by stabilizing or destabilizing FtsZ polymers would lead to bacterial cell death in a manner similar to, but different than that in eukaryotic cells, and (ii) the FtsZ-interacting agents should not have any resistance to the drug-resistant strains for current clinically used antibacterial drugs, since FtsZ is a totally new target for antibacterial agents.

In this review, we describe an account of our research on the development of new-generation taxoids, focusing on their interactions with microtubules as well as the discovery and development of novel FtsZ-interacting antibacterial agents, especially for treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

2. Microtubules and Taxoid Anticancer Agents

Among a variety of chemotherapeutic drugs, paclitaxel and docetaxel are currently two of the most widely used drugs for cancer chemotherapy, especially for the treatment of ovarian, breast, and lung cancers as well as kaposi’s sarcoma.17, 18 Further clinical applications are ongoing against different types of cancers as well as for combination therapies with other anticancer drugs.17 These “taxane” anticancer drugs bind to the β-tubulin subunit, accelerate the polymerization of tubulin, and stabilize the resultant microtubules, thereby inhibiting their depolymerization.19, 20 This results in the arrest of the cell division cycle mainly at the G2/M stage, leading to apoptosis through the cell-signaling cascade.

2.1. New-generation taxoids and their interaction with tubulin/microtubules

Although paclitaxel and docetaxel possess potent antitumor activity, it has been shown that treatment with these drugs often encounters undesirable side effects as well as drug resistance.17 Therefore, it is important to develop new taxane anticancer agents with fewer side effects, superior pharmacological properties, and improved activity against various classes of tumors, especially with drug-resistance to the first-generation taxane anticancer drugs. Accordingly, extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies on paclitaxel and its congeners have been performed for discovery and development of better taxane anticancer agents.7, 18, 21–29 In the course of our SAR study on taxoids derived from 10-deacetylbaccatin III, we found that (i) the C3’-phenyl group was not an essential component for their potent activity and (ii) the modifications of the C10 position with certain acyl groups as well as the replacement of the phenyl group with an alkenyl or alkyl group at the C3’ position made compounds 1–2 orders of magnitude more potent than the parent drugs (paclitaxel and docetaxel) against drug resistant human breast cancer cell lines. These highly potent taxoids were termed “second-generation taxoids”.30 Furthermore, we found that introduction of a substituent (e.g., MeO, N3, Cl, F, etc.) to the meta position of the C2-benzoyl group of the second-generation taxoids, enhanced the activities 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than the parent drugs against drug-resistant human breast cancer cell lines.7, 28 We have also developed a different series of second-generation taxoids derived from 14β-hydroxy-10-deacetylbaccatin III, isolated from the leaves of Himalayan yew tree, Taxus wallichiana Zucc. 23, 31 Among these novel taxoids, SB-T-101131 (IDN5109, ortataxel) received IND from FDA and advanced to Phase II human clinical trials.32 In addition, we have investigated fluorine-containing second-generation taxoids, bearing CF3, CF2H and 2,2-difluorovinyl groups at the C3’ position of the N-t-Boc-isoserine moiety at the C13 position.9–11, 33–38 Furthermore, we performed the SAR study on novel C-seco analogs of the second-generation taxoids for their activities against paclitaxel-resistant cancer cell lines overexpressing the Class III β-tubulin.39

2.1.1. Tubulin Polymerization: Rate Acceleration and Morphological Difference from Microtubules Treated with Paclitaxel

2.1.1.1. Characteristics of New-Generation Taxoids in Tubulin Polymerization

New-generation taxoids were found to possess exceptional activity in promoting tubulin assembly, forming numerous very short microtubules,8 in a manner similar to those formed by discodermolide that has been recognized as the most potent naturally occurring microtubule-stabilizing agent.40–43

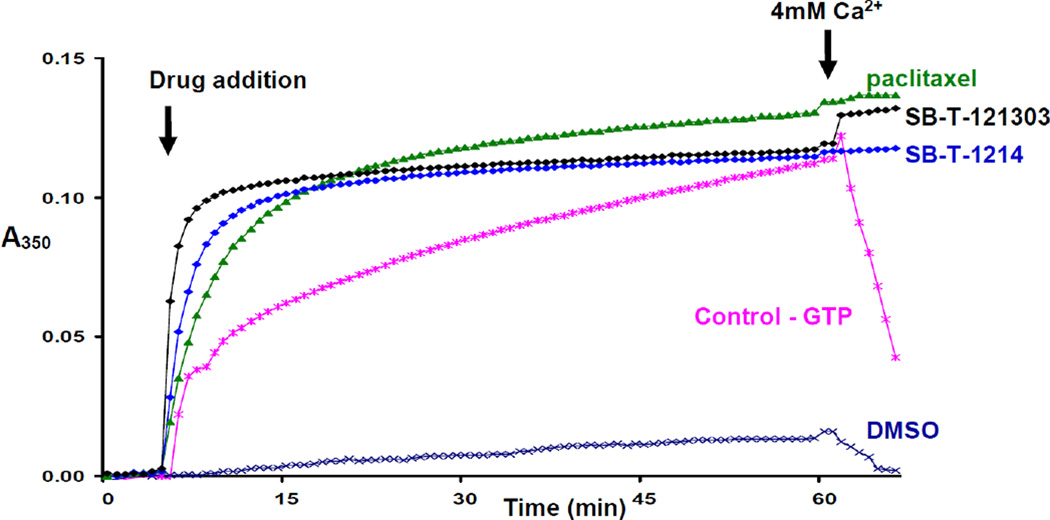

The activities of SB-T-1214, SB-T-121303, and SB-T-1213031 on tubulin/microtubule were evaluated by tubulin polymerization assays.8 Assembly and disassembly of calf brain microtubule protein (MTP) was monitored spectrophotometrically by recording changes in turbidity at 350 nm at 37 °C. MTP was diluted in MES buffer containing glycerol. The concentration of tubulin in MTP was 85%. Microtubule assembly was carried out with 10 µM taxoid. Paclitaxel (10 µM) was also used for comparison purpose. Calcium chloride was added to the assembly reaction after 50 min to follow the calcium-induced microtubule depolymerization.

Taxoids SB-T-1214, SB-T-121303, and SB-T-1213031 induced tubulin polymerization in the absence of GTP in a manner similar to paclitaxel (see Fig. 2 and 3), and the microtubules formed with these new-generation taxoids were stable against Ca2+-induced depolymerization.8 As Figure 2 shows, taxoids SB-T-1214 and SB-T-121303 promote rapid polymerization of tubulin at a faster rate than paclitaxel. The turbidity of the tubulin solution treated by SB-T-1214 or SB-T-121303 reaches a plateau quickly and does not change with time. This observation may imply that there is a difference in structure between microtubules formed with the new-generation taxoids and those with paclitaxel. Third-generation taxoid SB-T-121303 causes spontaneous tubulin polymerization, reaching >90% of a plateau within 5 min from onset, while it takes about 12 min for second- generation taxoid SB-T-1214 to reach the same point.8

Figure 2.

Tubulin polymerization with SB-T-1213, SB-T-121303 and paclitaxel: microtubule protein 1 mg/mL, 37 °C, GTP 1 mM, Drug 10 µM. Adapted with permission from reference 8.

Figure 3.

Tubulin polymerization with SB-T-1213031: microtubule protein 1 mg/mL, 37 °C, GTP 1 mM, Drug 10 µM. Adapted with permission from reference 8.

In a similar manner, the activity of taxoid SB-T-1213031 was compared with that of paclitaxel in a tubulin polymerization assay8 using a protocol for tubulin preparation slightly different from that used for the experiments presented in Figure 2. As Figure 3 shows, this assay reveals a remarkable difference in the rate of tubulin polymerization between the third-generation taxoid SB-T-1213031 and paclitaxel. SB-T-1213031 causes instantaneous polymerization of tubulin, completing the polymerization within 2 min, while paclitaxel promotes the polymerization much more slowly.8

The activities of three difluorovinyl taxoids, SB-T-12851, SB-T-12853 and SB-T-12854, for tubulin polymerization and microtubule stabilization were examined in comparison to paclitaxel.11 As Figure 4 shows, these three difluorovinyl taxoids induced GTP-independent tubulin polymerization much faster than paclitaxel. Thus, the turbidity of the tubulin solution treated with difluorovinyl taxoids reaches a plateau quickly and does not change with time. The resulting microtubules were stable to Ca2+-induced depolymerization, indicating strong stabilization of microtubules. This observation may suggest that the microtubules formed by these novel difluorovinyl taxoids are different from those formed by paclitaxel.11

Figure 4.

Tubulin polymerization with SB-T-12851, SB-T-12852, SB-T-12854, paclitaxel and GTP: microtubule protein 1 mg/mL, 37 °C, GTP 1 mM, Drug 10 µM. Adapted from reference 11.

SB-T-1213 and SB-T-101131 (IDN5109; ortataxel) are orally available taxanes that are up to 400-fold more active than paclitaxel against drug-resistant cells.30, 31, 44, 45 Ortataxel has advanced to Phase II human clinical trials.32 We investigated the primary target for SB-T-1213 and ortataxel, as well as whether the compounds interact with microtubules differently than paclitaxel.46 SB-T-1213 and ortataxel affect tubulin polymerization and microtubule structure differently from the classic taxane, paclitaxel, and they are more potent than paclitaxel, even in cells such as HeLa that are not multidrug resistant. SB-T-1213 stimulated tubulin polymerization in vitro with little or no lag of initiation. By turbidimetry, SB-T-1213 (1 and 10 µM) enhanced polymerization by 58% and 112%, respectively, more than paclitaxel.46

SB-T-1213 induces tubulin polymerization significantly more than paclitaxel. Paclitaxel also induced the formation of sheets, but they were fewer in number than with SB-T-1213 and the microtubules induced by paclitaxel were of normal appearance, rather than having partial microtubules or extra protofilaments associated with them. Ortataxel also potently stimulated tubulin polymerization in vitro with no detectable lag. The turbidimetric signal reached significantly higher levels than with paclitaxel (1 and 10 uM ortataxel, 24% and 75% higher than paclitaxel, respectively).46 Thus, both novel taxanes are equal or better than paclitaxel in their ability to enhance tubulin polymerization, while SB-T-1213 exhibits higher potency than ortataxel.

2.1.1.2. Electron Microscopy Analysis

The microtubules formed with new-generation taxoids (SB-T-1214, SB-T-121303, and SB-T-1213031) were analyzed further by electron microscopy for their morphology and structure in comparison with those formed by using GTP and paclitaxel.8 The electron micrographs of microtubules formed with three taxoids, paclitaxel, and GTP are summarized in Figure 5. As parts A and B of Figure 5 show, GTP and paclitaxel form long and straight microtubules. The microtubules formed with SB-T-1214 (Fig. 5C) are shorter than those with GTP or paclitaxel. In contrast, the morphology of the microtubules formed by the action of SB-T-121303 and SB-T-1213031 is unique in that those microtubules are very short and numerous (parts D and E of Fig. 5). The microtubules with SB-T-121303 appear to have more curvature than those with SB-T-1213031. It is worth mentioning that discodermolide40–43 forms microtubules with characteristics similar to those formed with SB-T-121303 and SB-T-1213031, i.e., short and numerous (Fig. 5F). It is strongly suggested that the formation of short and numerous microtubules is related to the instantaneous rapid polymerization of tubulin observed with these third-generation taxoids as well as discodermolide.8

Figure 5.

Electromicrographs of microtubules (20,000×): (A) GTP; (B) paclitaxel; (C) SB-T-1214; (D) SB-T-121303; (E) SB-T-1213031; (F) discodermolide. Adapted with permission from reference 8.

The microtubules formed by treatment of tubulin with three difluorovinyl taxoids, SB-T-12851, SB-T-12852 and SB-T-12854, were also analyzed by electron microscopy to study their morphology and structure in comparison to those formed in the presence of GTP or paclitaxel.11 The electron micrographs of microtubules formed by treatment with SB-T-12851, SB-T-12852, SB-T-12854, paclitaxel and GTP are shown in Figure 6.11 Microtubules formed in the presence of GTP and paclitaxel are long and thick (Fig. 6a and 6b), while those formed by the difluorovinyl taxoids (Fig. 6c–e) appear to be much thinner and shorter in length, which indicates substantial difference in their properties as compared to those formed by paclitaxel. It is strongly suggested that the formation of thinner and shorter microtubules is related to the rapid polymerization of tubulin observed with these difluorovinyl taxoids (see Fig. 4). There is some morphological similarity between those microtubules generated by the action of difluorovinyl taxoids and those by second-generation taxoids such as SB-T-1213 and SB-T-1214, but the formation of thinner, shorter and straight microtubules appear to be unique to difluorovinyl taxoids.11

Figure 6.

Electromicrographs of microtubules (20,000×): (a) GTP; (b) paclitaxel; (c) SB-T-12851; (d) SB-T-12852; (e) SB-T-12854. Adapted from reference 11.

SB-T-1213 induces the formation of unusual microtubules with attached extra protofilaments or open sheets, and ortataxel induces large protofilamentous sheets.46 As Figure 7 shows, ortataxel (A and B) induced the formation of large bundles of fibers (asterisk), large sheets (arrows), and a few microtubules. SB-T-1213 (C and D) induced the formation of microtubules (M) and a few sheets (arrows), partial microtubules, loops and coils (C), and long regions of a small number of protofilaments associated linearly with microtubules. Paclitaxel (1 µM) (E and F) induced the formation of many microtubules (M) and few sheets or loops. The scale bar in (A) represents 500 nm; that in (B) represents 100 nm. (A), (C), and (E) are at the same magnification, as are (B), (D), and (F). The marked tendency of ortataxel and SB-T-1213 to induce the polymerization of tubulin into sheets and other aberrant microtubule-like forms suggests that these new-generation taxoids induce conformational changes in tubulin/microtubules that differ significantly from the conformational changes induced by paclitaxel.

Figure 7.

Tubulin polymers induced by 1 µM ortataxel or 1 µM SB-T-1213, as compared to paclitaxel.

Electron micrographs: left column, low magnification; right column, high magnification. Adapted from reference 46.

Figure 8 shows HeLa cells incubated with no drug (A and B), 1 nM SB-T-1213 (C and D), or 3 nM IDN5109 (E and F) for 20 h, followed by fixation and staining for tubulin (A, C, and E) and chromosomes (B, D, and F).46 In the absence of drug (A and B), metaphase spindles are bipolar with compact metaphase plates of chromosomes (arrow). At low concentrations of SB-T-1213 (1 nM), spindles are bipolar or multipolar (arrow in C), and chromosomes often fail to congress to the metaphase plate and instead remain at the poles (arrows in D). At low concentrations of ortataxel, similar abnormalities occur. Two multipolar spindles (arrows in E) as well as one cluster of three small cells resulting from an aberrant incomplete cytokinesis (arrows in F) are shown in (E) and (F). The resulting cells are multinucleate (arrows in F). These differences in their interactions with tubulin and microtubules may play a direct role in their enhanced cytotoxic potency and antitumor efficacy.46

Figure 8.

Induction of abnormal spindles by SB-T-1213 and ortataxel. The scale bar represents 10 µm. Adapted from reference 46.

2.1.2. Mitotic Arrest and Induction of Apoptosis: Similarity and Difference between Paclitaxel and New-Generation Taxoids

SB-T-1213 and ortataxel induced apoptosis at the same concentrations that induced mitotic block in HeLa cells.46 The TUNEL assay disclosed that the incubation of HeLa cells with these two taxoids at concentrations as low as 2.5 nM for 24 h induced apoptosis. Higher concentrations of paclitaxel (5 nM) were required for induction of apoptosis. The percentage of cells that were apoptotic reached 70% with 5 nM SB-T-1213, 40% with 5 nM ortataxel, and 25% with 5 nM of paclitaxel at 24 h. These data indicate that apoptosis was strongly correlated with mitotic block. Flow cytometry analysis, combining results of the TUNEL assay with that of cellular DNA content, indicates that most apoptotic cells arise from cells that remain blocked at the G2/M stage of the cell cycle or from cells blocked at G2/M that subsequently reenter interphase without undergoing cytokinesis.46

The effects of a second-generation taxoid, SB-T-1216 as well as fluoro-taxoids, SB-T-12851, SB-T-12852, SB-T-12853 and SB-T-12854, were examined by employing two human cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-435 (paclitaxel-sensitive) and NCI/ADR (highly paclitaxel-resistant).47 It was found that the cell death-inducing effect of these new-generation taxoids is significantly higher than paclitaxel, especially against NCI/ADR cells. Although the effective concentration of new-generation taxoids is much lower than that of paclitaxel, the mechanism leading to apoptosis is essentially the same. The cell death induced by new-generation taxoids examined as well as paclitaxel against these two cell lines was accompanied by the activation of caspase-3, caspase-9, caspase-2 and caspase-8, but not associated with increased level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial membrane potential collapse and cytochrome C release from mitochondria. It was suggested that the key event of the induction of apoptosis by the taxanes examined against the two cancer cell lines is the activation of caspase-2. Caspase-2 may act as the most apical caspase that is responsible for the activation of all other caspases including caspase-9.47

2.1.3. Activities against paclitaxel-resistant cell lines, including point mutations and class III β-tubulin

2.1.3.1. Cytotoxicity of new-generation taxoids against paclitaxel-resistant cancer cells with point mutations in tubulin

Multidrug-resistance to paclitaxel arises from the overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters,48 but other drug-resistance mechanisms are also involved in paclitaxel-resistance.49 One of the significant mechanisms is associated with alterations of its cellular target, tubulin/microtubule.50–55 In this regard, two paclitaxel-resistant sublines 1A9PTX10 and 1A9PTX22, derived from 1A9 cell line, have been reported.54 The parental 1A9 is a clone of the human ovarian carcinoma cell line A-2780. Point mutations in class I β-tubulin in both 1A9PTX10 and 1A9PTX22 have been identified by sequence analysis.54 Thus, the cytotoxicity of new generation taxoids against these two paclitaxel-resistant cell lines would provide critical information about their ability to deal with drug-resistance other than MDR. Selected new generation taxoids, SB-T-1214, SB-T-121303, and SB-T-11033, were assayed against both drug-resistant cell lines and the parental cell line. As Table 1 shows, all three taxoids exhibit extremely potent activity, especially against drug-resistant cell lines 1A9PTX10 and 1A9PTX22, with two orders of magnitude higher potency than paclitaxel. The results clearly demonstrate that these second- and third-generation taxoids possess capability of effectively circumventing the paclitaxel drug-resistance arising from point mutations in tubulins/microtubules besides MDR. This makes the new-generation taxoids even more attractive.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of new generation taxoids against 1A9PTX10 and 1A9PTX22 cell lines (IC50 nM)

| Taxoids | A-2780 | 1A9PTX10 | R/Sa | 1A9PTX22 | R/Sa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | 1.38±0.05 | 532.95±3.18 | 386 | 160.70±14.70 | 116 |

| SB-T-1214 | 0.44±0.04 | 9.00±0.77 | 20.4 | 3.94±0.03 | 9.0 |

| SB-T-121303 | 0.76±0.01 | 3.65±0.21 | 4.8 | 3.88±0.54 | 5.1 |

| SB-T-11033 | 0.25±0.01 | 4.91±0.53 | 19.6 | 2.10±0.13 | 8.4 |

Resistance factor = (IC50 for drug resistant cell line, R)/ (IC50 for drug-sensitive cell line, S).

2.1.3.2. Cytotoxicity of C-seco-taxoids against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cell lines overexpressing class III β-tubulin

In spite of extensive efforts devoted to overcoming resistance to anticancer drugs, a prominent mechanism of drug resistance, which has not been successfully addressed yet, is related to the overexpression of specific tubulin isotypes.55–58 Tubulin dimers, derived from different β-isotypes have different behaviors in vitro in regard to assembly, dynamics, conformation and ligand binding.56, 57, 59–61 In analogy, microtubules with altered β-tubulin isotype composition have different dynamics in response to paclitaxel.62

It was reported that novel C-seco-taxoid, IDN 5390, is up to 8-fold more potent than paclitaxel against the inherently drug-resistant cell line OVCAR3 and paclitaxel-resistant human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines, A2780TC1 and A2780TC3.63 To further explore the potential of C-seco-taxoids, a new series of C-seco-taxoids were designed, synthesized, and their potencies evaluated against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cell lines.39 The chemical structures of these C-seco-taxoids are shown in Figure 9. The drug-resistant cell lines include ovarian cancer cell lines resistant to cisplatin, topotecan, adriamycin and paclitaxel overexpressing class III β-tubulin, A2780TC1 and A2780TC3. The last two cell lines were selected through chronic exposure of A2780wt to paclitaxel and Pgp blocker cyclosporine. All novel C-seco-taxoids exhibited remarkably higher potency than paclitaxel against A2780TC1 and A2780TC3 cell lines, and no cross resistance to cisplatin- and topotecan-resistant cell lines, A2780CIS and A2780TOP.

Figure 9.

C-Seco-taxoids

As Table 2 shows, all new C-seco-taxoids possess significant potency against the paclitaxel-resistant cell line, A2780TC3, that is, the most drug-resistant cell line for paclitaxel in this series (24–84 times more potent than paclitaxel and 3–11 times more potent than IDN 5390). The resistance factor for this cell line, that is, IC50 (A2780TC3)/IC50 (A2780wt), is 10,470 for paclitaxel, but it is only 31 for SB-CST-10101. For comparison, IDN 5390 exhibits 8.0 times higher potency than paclitaxel with a resistance factor of 129 against the same cell line. These results are quite impressive by taking into account the fact that the only structural difference between IDN 5390 and these C-seco-taxoids is one substitution at the meta position of the C2-benzoate moiety of the C-seco-taxoid molecule. These C-seco-taxoids also exhibit 2.3–13 times higher potency than paclitaxel against the A2780TC1 cell line, and more potent than IDN5390 except SB-CST-10204. The resistance factor of paclitaxel for this cell line is 5,898, but that of SB-CST-10202 is 163. The potencies of these C-seco-taxoids against A2780CIS and A2780TOP do not show any appreciable cross resistance, as anticipated. Overall, SB-CST-10202 appears to be the best drug lead with all-round high potencies across different drug-resistant cell lines.39

Table 2.

IC50 (nM) of C-Seco-Taxoids

| R | X | A2780wta | A2780CISb | A2780TOPc | A2780ADRd | A2780TC1e | A2780TC3e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | 1.7±1.2 | 2.2±0.2 | 7.2±1.5 | 1,239±265 | 10,027±3,195 | 17,800±5,499 | ||

| IDN 5390 | Me2CHCH2 | H | 17.4±1.5 | 16.8±3.1 | 27.5±5.1 | 2,617±1,028 | 2,060±344 | 2,237±471 |

| SB-CST-10101 | Me2CHCH2 | OMe | 6.8±3.6 | 4.3±1.0 | 3.5±1.6 | 356±74 | 1,121±454 | 211±50 |

| SB-CST-10102 | Me2CHCH2 | Cl | 5.5±3.3 | 4.1±1.8 | 4.6±1.3 | 604±246 | 1,801±988 | 385±6.0 |

| SB-CST-10104 | Me2CHCH2 | F | 11.1±8.4 | 11.8±1.0 | 12.8±3.5 | 3,726±198 | 1,497±31 | 460±128 |

| SB-CST-10201 | Me2C=CH | OMe | 4.6±3.2 | 5.7±2.4 | 2.6±1.9 | 386±181 | 1,057±185 | 490±212 |

| SB-CST-10202 | Me2C=CH | Cl | 4.6±0.4 | 4.0±0.1 | 1.7±0.4 | 452±28 | 751±11 | 357±126 |

| SB-CST-10204 | Me2C=CH | F | 6.1±0.6 | 4.9±0.2 | 6.9±0.8 | 2,218±588 | 4,454±1,391 | 745±60 |

Human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line (wild type).

Cisplatin-resistant cell line.

Topotecan-resistant cell line.

Adriamycin (doxorubicin)-resistant cell line.

paclitaxel-resistant cell line overexpressing class III β-tubulin.

Molecular modeling studies on the drug-protein complexes of class I and III β-tubulins were performed to identify possible cause of the remarkably higher potency of these C-seco-taxoids than paclitaxel against drug-resistant cell lines overexpressing class III β-tubulin.39 Following up recent molecular modeling studies of paclitaxel and IDN5390 in human class I and III β-tubulin,63, 64 we employed molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to predict the binding conformation of C-seco-taxoids in class I and III β-tubulins. A cryo-EM crystal structure of bovine brain tubulin (1JFF)65 was used as the template to create 3-D class I and III β-tubulin models, TubB1 and TubB3, respectively. Overlay of paclitaxel, IDN5390 and SB-CST-10202 is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Snapshots of SB-CST-10202 in TBB1 (yellow) and TBB3 (cyan). Adapted from reference 39.

This study has demonstrated that the meta-substitution of the C2-benzoate moiety of C-seco-taxoids with appropriate groups can substantially increase the interaction of C-seco-taxoids with the class III β-tubulin to overcome paclitaxel-resistance, due to the over-expression of this particular subclass of β-tubulin.39 SB-CST-10202 was identified as the most promising drug lead, exhibiting all-round high potencies across different drug-resistant cell lines. Molecular modeling study on the tubulin-bound conformations of paclitaxel, IDN5390 and SB-CST-10202 in TubB1 and TubB3 showed considerable difference in their conformations between the two β-tubulin subclasses. This study strongly supported the importance of hydrophobic interaction between the C2-benzoyl moiety and His227.39

2.1.4. Fluorescence-labeled Taxoids and Their use in Chemical Biology

In order to study the interaction of paclitaxel with tubulin/microtubule system and visualize the microtubule dynamics in the presence of paclitaxel, various spectroscopic methods have been applied. One of the most useful techniques to explore such interactions is fluorescence spectroscopy, in which various probes derived from paclitaxel or its derivatives with a fluorophore tag are used.66 Most of taxane-based fluorescent probes are prepared from paclitaxel, by introducing a fluorophore at C-7 position through proper linkage.

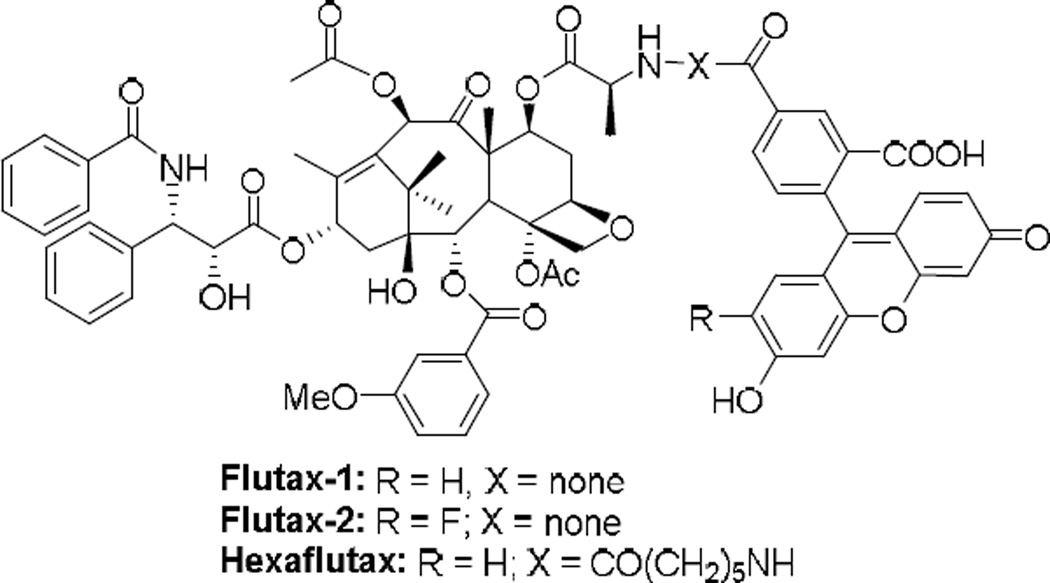

Three fluorescent probes, Flutax-1, Flutax-2 and Hexaflutax, have been developed through conjugation of the fluorescein group to the 7-OH of paclitaxel, which possess very high affinity to microtubules (Figure 11). These probes exhibited potent tubulin assembly promotion and tumor cell killing activities, thus have been proven to be useful as tools for the determination of thermodynamic parameters and exploration of ligand–microtubule interactions.66, 67

Figure 11.

Fluorescence probes of paclitaxel

Fluorescence-labeled SB-T-1214 (SB-T-1214-fluorescein) has been successfully used for monitoring tumor-targeting, receptor-mediated endocytosis, linker cleavage, drug release, and drug binding to the target protein (i.e., microtubules) of a tumor-targeting drug conjugate, BLT.68 BLT-fluorescein consists of biotin (tumor-targeting module), a self-immolative linker, and SB-T-1214 (warhead) as shown in Figure 12. SB-T-1214-fluorescein has also been used as a control probe for evaluating the cancer cell specificity of BLT-fluorescein against a biotin-overexpressing cell line (L1210FR) and normal human lung fibroblast cell line (WI38).68 The confocal fluorescence microscopy (CFM) images are shown in Figure 13. SB-T-1214-fluorescein unit has also been successfully employed for monitoring the efficacy of a “Trojan Horse” tumor-targeting nano-drug conjugate using single-walled carbon nanotubes as the vehicle.69

Figure 12.

Fluorescence probes of SB-T-1214 and its tumor-targeing conjugate, BLT.

Figure 13.

(A) CFM image of L1210FR cells after incubation with BLT-fluorescein. (B) CFM image of L1210FR cells that were initially incubated with BLT-fluorescein, followed by treatment with GSH-OEt to release SB-T-1214-fluorescein. Then, the microtubule network in the cells was fluorescently labeled and visualized. Adapted with permission from reference 68.

2.2. Bioactive conformations of paclitaxel and taxoids in microtubules

The polar and nonpolar conformations of paclitaxel were first proposed based on the structural analysis in solution and in the solid state using NMR and X-ray crystallography.70–74 Organic and medicinal chemists designed a series of structurally restrained taxoids to mimic these two conformations, but all of the synthesized taxoids were substantially less active than paclitaxel.75–77 The structural biology study of paclitaxel did not start until the first cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of paclitaxel-bound Zn2+-stabilized α,β-tubulin dimer was reported in 1998 at 3.7 Å resolution (1TUB structure),78 which used the docetaxel crystal structure for display. The 1TUB structure was later refined to 3.5 Å resolution with a paclitaxel molecule (1JFF structure) in 2001.79 However, the resolution of these cryo-EM structures was not high enough to solve the binding conformation of paclitaxel. Thus, a computational study of the electron-density map was performed, which led to the proposal of the “T-Taxol” conformation.80 To prove the validity of the “T-Taxol” structure, rigidified paclitaxel congeners were designed, synthesized and assayed for their tubulin polymerization ability and cytotoxicity.75, 81–84 Among those “T-Taxol” mimics, C4-C3’–linked macrocyclic taxoids showed higher activities than paclitaxel in the cytotoxicity and tubulin-polymerization assays.81, 83

In the mean time, two 13C-19F intramolecular distances of the microtubule-bound 2-(4-fluorobenzoyl)paclitaxel were experimentally obtained by means of the REDOR NMR study in 2000.85 On the basis of the REDOR distances, MD analysis of paclitaxel conformers, photoaffinity labeling86 and molecular modeling studies using the 1TUB coordinate78, we proposed the “REDOR-Taxol” as a valid microtubule-bound paclitaxel structure in 2005.87, 88 We have further refined the “REDOR-Taxol” using the 1JFF coordinate and found that the “REDOR-Taxol” is not only fully consistent with the new REDOR-experiments, 89 but also accommodates highly active macrocyclic paclitaxel analogs designed based on the “T-Taxol” structure.88 The critical difference between these two structures is the orientation of the C2’-OH group. In the “REDOR-Taxol”, the C2’-OH group interacts with His227 as the hydrogen bond donor,87 while the H-bonding is between the C2’-OH and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Arg369 in the “T-Taxol”. 80 Accordingly, we designed novel macrocyclic taxoids by linking the C14 and C3’BzN groups (Fig. 14), which mimic the “REDOR-Taxol” structure to examine whether these conformationally restricted taxoids exhibit the same level of biological activity as that of paclitaxel.90

Figure 14.

Macrocyclic taxoids mimicking the microtubule binding structure of paclitaxel

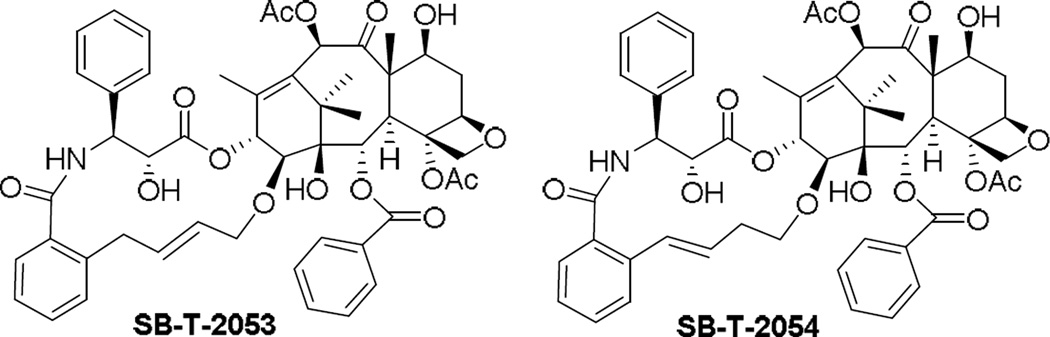

We synthesized SB-T-2053, a C14-C3’N-linked macrocyclic taxoid using ring-closing metathesis in the key step.90, 91 Molecular modeling anticipates decreased conformational flexibility for the C13 side chain of SB-T-2053 while still allowing the adoption of either REDOR-taxol or T-taxol conformation. The macrocyclic taxoid SB-T-2053 possesses significant potency against human breast cancer cell lines comparable to that of paclitaxel. Moreover, SB- T-2053 induces tubulin polymerization in vitro at least as well as paclitaxel, which directly validates our design process. SB-T-2054 was synthesized through a novel Ru-catalyzed intramolecular coupling of two ethenyl moieties, which gave 15-membered macrocyclic taxoid instead of designed 14-membered macrocycle.90 SB-T-2054 exhibits higher potency than SB-T-2053 against several human breast, ovary and colon cancer cell lines. It is noteworthy that SB-T-2054 exhibits virtually the same potency as that of paclitaxel in the cytotoxicity and tubulin-polymerization assays as well as morphology analysis of microtubules by electron microscopy, which may indicate that the SB-T-2054 structure almost perfectly mimics the bioactive conformation of paclitaxel.90

The microtubule-bound structure of SB-T-2054 was energy minimized in the 1JFF coordinate and overlaid with the “REDOR-Taxol” structure in the 1JFF β-tubulin, as shown in Figure 15.90 We also performed the Monte Carlo conformational analysis of SB-T-2054. We started from the “REDOR-Taxol” conformation as well as the “T-Taxol” conformation, but both converged to the same distribution of conformers. The results indicate that the X-ray crystal structure of SB-T-2054 is just one of the preferred conformations in a crystalline state. Also, the dihedral angle of C13-C1″-C2″-O2″ of SB-T-2054 does not match those of the “REDOR-Taxol” and the “T-Taxol”, which may suggest that both proposed bioactive conformations of paclitaxel need further refinements.88, 90

Figure 15.

Overlays of REDOR-Taxol (green) with SB-T-2054 (purple). Adapted with permission from reference 90.

3. FtsZ and Antibacterial Agents

3. 1. FtsZ – Filamentous Temperature Sensitive Protein Z

Unlike drugs designed for eukaryotic cells, cytokinesis remains largely unexploited for the development of novel bacterial therapeutics. Filamentous temperature-sensitive protein Z (FtsZ), a tubulin homolog, is the most abundant bacterial cell division protein. In the presence of GTP, FtsZ polymerizes bi-directionally at the center of the cell on the inner membrane to form a highly dynamic helical structure known as the “Z-ring”.12–16 The recruitment of several other cell division proteins leads to Z-ring contraction, resulting in septum formation and eventually cell division (Fig. 16).92

Figure 16.

Graphic presentation of Z-ring formation and cell division. (A) Bacterial cell before the beginning of cell division with FtsZ protofilaments scattered in the cell and undergoing continuous nucleotide exchange between GTP-bound FtsZ and GDP-bound FtsZ with rapid equilibrium, favoring GTP-bound FtsZ (B) Cell elongation and chromosome segregation, localization of FtsZ protofilaments at the mid cell. (C) Formation of Z-ring: the ‘steady-state turnover’- GTP hydrolysis competes continuously with protofilament growth during polymerization. (D) Formation of septum and subsequent constriction of the Z-ring followed by membrane fluctuation to bring about cell division.

3.1.1. Biological Role of FtsZ

FtsZ is the most essential and highly conserved cytoplasmic protein in prokaryotes.93, 94 In the presence of GTP, at a critical concentration of 0.5–1 µM of FtsZ,95–97 FtsZ subunits are believed to display cooperative assembly to form single stranded protofilaments. They stack in a head to tail fashion, with GTP sandwiched between two FtsZ subunits.95, 98, 99 Extensive lateral interaction between these overlapping protofilaments leads to the formation of a highly dynamic ring structure known as the “Z-ring”.95 Although the structure of the Z-ring formed in vivo is not well understood, it has been suggested that its architecture might consist of a large number of short, overlapping protofilaments rather than a continuous ring.100

While many of the proteins involved in chromosomal segregation and cell division are conserved across the taxa, others appear limited to Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria. Analysis of the Mtb genome sequence revealed that many of the genes that encode proteins involved in regulation of septum formation and cell division are not annotated.101 Much of what is known is derived from the studies in model organisms like E. coli, B. subtilis.102, 103 It has been shown that an essential requirement for the formation of the Z-ring is the anchoring of FtsZ to the cell membrane through either FtsA or ZipA (accessory proteins), both of which are known to bind to the conserved C-terminal domain of FtsZ.102, 103 However, it has been revealed that only one of them is required for Z-ring formation but both ZipA and FtsA are necessary for proper cytokinesis.103 Since the requirement of ZipA can be bypassed by a mutation in FtsA and given that FtsA is widely conserved compared to ZipA, FtsA is believed to be the crucial factor responsible for maintaining the Z-ring integrity.93, 104

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) along with other studies have revealed that the Z ring is very dynamic and continuously exchanging the subunits from a pool of cytoplasmic FtsZ before and during constriction. The rate of the steady-state turnover depends on the GTPase activity of the FtsZ polymer.105, 106 Rapid turnover with no effect on the integrity of the Z-ring further suggests that it consists of short filaments of FtsZ interacting laterally with each other, presumably held together by FtsA/ZipA.92, 107

The relation between FtsZ polymerization and GTP hydrolysis to GDP is crucial for the integrity of the Z-ring (Fig. 17). It has been shown that GTP-bound FtsZ polymerizes into straight polymers, which triggers the GTPase activity of FtsZ, because the catalytic site is formed at the interface of two adjacent FtsZ monomers.108, 109 Upon GTP hydrolysis, polymers bound to GDP were thought to favor curved conformation as opposed to straight polymers.110 It has been proposed that the GTP hydrolysis generates a force during septation where nucleotide-dependent transitions from straight to a curved polymer can transmit mechanical work to the membrane leading to the constriction of the Z-ring.100, 110 However, the physiological role of this force remains controversial as accounted by several experiments where FtsZ mutants with undetectable GTPase activity could still divide suggesting that FtsZ’s GTPase activity is not the source of power during constriction of the septum but is important for symmetrical invagination.111, 112

Figure 17.

Polymerization-depolymerization dynamics of FtsZ. (A) Nucleotide exchange between GTP-bound FtsZ and GDP-bound FtsZ with rapid equilibrium, favoring GTP-bound FtsZ (B) Polymerization begins and long-straight protofilaments starts to form after a critical concentration of GTP-bound FtsZ is achieved. (C) The ‘steady-state turnover’ - GTP hydrolysis competes continuously with protofilament growth during polymerization. (D) After bacterial cell division occurs, distorted GDP-bound FtsZ protofilaments depolymerize to yields FtsZ monomers.

Recent experiments with liposomes (tubular membrane) and observation of curved and straight protofilaments in vivo demonstrated that the protofilament bending is more likely to be a plausible mechanism for producing the constriction force.100, 113 However it is believed that the curved conformation of the protofilaments itself cannot pull the membrane to complete scission.92 It has been suggested that the final step of scission can be completed by membrane fluctuations.92 The remodeling of the cell wall, which starts from the membrane invagination, may become a positive force pushing the septum toward closure, leading to final scission.92, 114, 115

3.1.2. FtsZ and Tubulin: Structural and functional homology

The fact that FtsZ is a homologue of tubulin was first realized via the identification of a short amino acid sequence, GGGTGTG, from the crystal structure of Methanococcus jannaschii FtsZ (Mj-FtsZ; PDB: 1W5A), that is virtually identical to the tubulin signature motif, (G/A)GGTGSG, found in all α-, β- and γ-tubulins.13 Despite limited (10–18%) sequence similarity,116 FtsZ and tubulin share a common fold, comprised of two domains linked by an α-helix.117 The residues involved in the nucleotide binding domain and a region involved in protofilament formation in tubulin are found to be conserved.117 Like tubulin, FtsZ polymerizes in the presence of GTP into 5 nm wide protofilaments while depolymerizing upon GTP hydrolysis.14 In spite of their similarity, these two proteins differ in several ways.14 Unlike FtsZ, where identical subunits form protofilaments (Fig. 18),14 microtubules are formed from different subunits, α- and β-tubulin.14 Because of the structural and functional homology, compounds that are known to affect the assembly of tubulin into microtubules, can act as a lead for targeting FtsZ assembly. The limited sequence homology at protein level provides the opportunity to discover FtsZ-specific compounds with limited cytotoxicity to eukaryotic cells.

Figure 18.

Crystal structure of homo-dimer Mtb-FtsZ bound to GTPγS (PDB:1RLU) at 2.08 Å resolution. Adapted from Reference 14.

3.2. FtsZ-A novel target for anti-TB drug discovery

As described above, FtsZ, an essential bacterial cytokinesis protein, has emerged as a highly promising new target for the discovery of novel antibacterial agents. It was hypothesized that inhibition of proper FtsZ assembly would prevent septum formation, giving way to continued cell filamentation, ultimately leading to cell death.101, 118 As FtsZ is essential and highly conserved in prokaryotes, in addition to being pathogen specific, FtsZ inhibitors may be developed as broad-spectrum antibacterial agents to which acquiring resistance by mutations in the protein may be demanding for bacteria.94, 119 Recently, Haydon et. al. have isolated staphylococcal strains resistant to anti-FtsZ compounds with relatively low frequency, reiterating the difficulty in developing resistance.120 This suggests that resistance mechanisms against compounds developed for FtsZ inhibition may not be widespread in nature. Accordingly, FtsZ is a very promising target to develop new generation antibacterial drugs. A good number of compounds have already been identified to target FtsZ.121–123 As FtsZ and tubulin have close functional homology,124–126 compounds that are known to inhibit or stabilize tubulin/microtubules can serve as a good starting point for the discovery and development of novel antibacterial agents.122, 123, 127–129 After modifications, these tubulin inhibitors can be made specific to target FtsZ with no appreciable cytotoxicity to eukaryotic cells. Although drug development in this field is still in an early stage, several classes of compounds have been found effective against Mtb FtsZ and a number of compounds have been identified as promising leads. These compounds are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mtb-FtsZ Inhibitors

| Compound | Mode of action |

|---|---|

| SRI-3072, SRI-7614, 2-carbamoyl-pteridine 130, 131 Pyridopyrazine analogue of SRI-3072132 | Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization and GTPase activity |

| Taxanes127 | FtsZ polymer stabilization |

| Benzimidazoles129 | Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization; GTPase activity enhancement |

| 6-Chloro-N-(4-propoxyphenyl)quinolin-4-amine133 | Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization |

| Zantrins 134 | Inhibits GTPase activity |

3.2.1. Taxanes

Paclitaxel (Taxol®), a microtubule-stabilizing anticancer agent, exhibits modest antibacterial activity against drug-sensitive and drug-resistant Mtb strains (MIC 40 µM), although its cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines (a benchmark for activity against human host cells) is three orders of magnitude more potent (IC50 0.019–0.028 µM). Following the hypothesis that compounds that affect tubulin/microtubule would serve as leads for developing FtsZ inhibitors, a library of taxanes was screened for antibacterial activity against Mtb cells.127 Real time PCR-based assay was employed to screen cytotoxic taxanes that stabilize microtubules135–137 as well as non-cytotoxic taxane-multidrug resistance reversal agents (TRAs)138–144 that inhibit the efflux pumps of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp).

Of the 120 taxanes screened, SB-RA-2001 was found to exhibit significant anti-TB activity, but with moderate cytotoxicity.127 It has been shown that novel anti-angiogenic taxoid, IDN5390,145, 146 bearing a C-seco-baccatin moiety possesses substantially less cytotoxicity than paclitaxel. Therefore, C-seco analogs of SB-RA-2001 were designed, synthesized and evaluated. These novel C-seco-taxanes, SB-RA-5001 and its congeners (Fig 19), were found to exhibit promising anti-TB activity (MIC99 1.25–2.5 µM) against drug-sensitive strain H37Rv as well as drug-resistant Mtb strain IMCJ946.K2 (resistant to isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, kanamycin, p-aminosalicilic acid, cycloserine and enviomycin) without appreciable cytotoxicity (IC50 > 80 µM).127 Thus, the specificity of these novel taxanes to microtubules as compared to FtsZ was completely reversed.

Figure 19.

Mtb FtsZ inhibitors: Taxanes

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Mtb cells treated with SB-RA-20018 and SB-RA-5001 clearly show substantial elongation and filamentation, a phenotypic response to FtsZ inactivation (Fig. 20).127 In addition, SB-RA-5001 has been shown to stabilize Mtb-FtsZ polymers and this effect was visualized by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 21). Mtb FtsZ (5 µM) was polymerized in the presence of GTP (25 µM) at 37 °C for 30 min. The polymerized FtsZ was diluted 20 folds which resulted in depolymerization/disassembly of the polymers/aggregates since the protein concentration dropped below the threshold value. On the other hand, Mtb-FtsZ treated with SB-RA-5001 was not susceptible to dilution-induced depolymerization as the compound stabilizes the polymers. These preliminary results give an insight into the mode of action of this series of compounds, which is similar to the effect of taxane-based compounds on tubulin/microtubule.

Figure 20.

Electron micrograph of Mtb cells: (A) Control, (B) SB-RA-20018 and (C) SB-RA-5001. Adapted with permission from reference 127.

Figure 21.

TEM Images of FtsZ. FtsZ (5 µM) was polymerized by GTP (25 µM) in the absence (A) and presence of SB-RA-5001 (160 µM) (C). After 30 min, the polymerized FtsZ was diluted 20 folds with buffer. TEM images display the dilution-induced depolymerization of the untreated FtsZ protein (B) since the FtsZ concentration drops below the threshold value. The SB-RA-5001 treated FtsZ (D) does not depolymerize upon dilution because the compound stabilizes the FtsZ polymer. Images are at 68,000× magnification (scale bar 100 nm).

3.2.2 Benzimidazoles

3.2.1.1. Antitubercular activities of trisubstituted benzimidazoles

Albendazole and thiabendazole are known inhibitors of tubulin polymerization. It has been shown that thiabendazole caused cell elongation in E. coli and cyanobacteria, which suggests that these tubulin inhibitors may act in a similar manner on the ftsz gene product as they do on tubulin.147 Based on the similarity of the benzimidazole moiety to the pyridopyrazine131 and pteridine130 pharmacophores in the FtsZ inhibitors identified by researchers at the Southern Research Institute, it was hypothesized that the benzimidazole framework might be a promising starting point for the development of novel FtsZ inhibitors. Several solid- or solution-phase synthetic methods for mono- or disubstituted benzimidazoles were reported, but few dealt with the synthesis of trisubstituted benzimidazoles. Furthermore, based on thorough literature search, there were very few trisubstituted benzimidazoles known in literature and they were not investigated for their antibacterial activity. Consequently, 2,5,6- and 2,5,7-trisubstituted benzimidazoles, were selected as the basic scaffold for the synthesis of novel benzimidazole libraries using systematic and rational design.129

The libraries of 2,5,6- and 2,5,7-trisubstituted benzimidazoles (~1,100 compounds) were synthesized and screened using the “Microplate Alamar Blue assay (MABA)”148 in a 96-well format (single point assay in triplicates).129 Of these, 204 compounds were identified to inhibit the growth of Mtb H37Rv with MIC values ≤5 µg/mL. Furthermore, among the 204 hits, 56 selected compounds were resynthesized, which showed MIC values of 0.06–6.1 µg/mL. The structures of 12 most potent compounds are shown in Table 4.129, 149

Table 4.

Antitubercular activities of lead benzimidazoles

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | MIC99 (µg/mL) H37Rv |

| SB-P3G2 | 0.63 | ||

| SB-P8B2 | 0.39 | ||

| SB-P17G-C2 | 0.06 | ||

| SB-P17G-C4 | 0.16 | ||

| SB-P20G3 | 0.16 | ||

| SB-P17G-A20 |  |

0.16 | |

| SB-P21G4 | 0.31 | ||

| SB-P21G7 | 0.31 | ||

| SB-P17G-C8 | 0.31 | ||

| SB-P17C-A28 | 0.31 | ||

| SB-P17G-C12 | 0.63 | ||

| SB-P26D2 |  |

0.63 | |

Preliminary SAR studies indicates that cyclohexyl at the 2-position and dimethylamino, diethylamino and pyrrolidine groups at the 6-positions are critically important for antibacterial activity of 2,5,6-trisubstituted benzimidazoles. Additionally, an ether or a thioether linkage at the 6-position are also tolerated. A carbamate group is better than an amide group at the 5-position for anti-tubercular activity. Five lead compounds, SB-P3G2, SB-P8B2, SB-P17G-C2, SB-P20G3 and SB-P17G-A20, were tested against clinical isolates of Mtb strains W210 (drug-sensitive), NHN382 (isoniazide-resistant; Kat G S315t mutation) and TN587 (isoniazide-resistant; KatG 3315T mutation). As anticipated, they showed no difference in potency between the drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains exhibiting excellent MIC values in the range of 0.06–1.25 µg/mL (Table 5).129, 149

Table 5.

Antitubercular activities of lead benzimidazoles against drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant Mtb strains

| Compound | MIC99 (µg/mL) Mtb strains |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv | NHN382 | TN587 | W210 | |

| SB-P3G2 | 0.63 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| SB-P8B2 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.63 |

| SB-P17G-C2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| SB-P20G3 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| SB-P17G-A20 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

3.2.2.2. Biological evaluations of lead benzimidazoles

FtsZ polymerization assay150 was carried out to confirm that these lead compounds exhibit antibacterial activity by interacting with FtsZ. Two most active benzimidazoles, SB-P3G2 and SB-P17G-C2, were selected and evaluated for their ability to inhibit the polymerization of the wild-type FtsZ. The assays confirmed that the compounds inhibited polymerization of FtsZ in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 22).129, 149 In the case of SB-P3G2, 50 % inhibition was observed at 10–20 µM concentration and the polymerization was completely inhibited at 40 µM concentration.129 Similar result was observed for compound SB-P17G-C2.149

Figure 22.

Inhibition of FtsZ Polymerization by SB-P3G2 and SB-P17G-C2

Also SB-P3G2 has been shown to enhance the GTPase activity of Mtb-FtsZ.129 Enhancement in the GTPase activity together with the fact that these compounds inhibit polymerization of Mtb-FtsZ, has led us to conclude that the increased GTPase activity causes the instability of Mtb-FtsZ polymer. As a result of the instability, Mtb-FtsZ is unable to polymerize normally, leading to the efficient inhibition of the formation of sizable Mtb-FtsZ polymers and filaments.

To further investigate the effect of the hit compounds on polymerization of FtsZ protein, TEM imaging of Mtb-FtsZ protein was carried out. Mtb-FtsZ protein treated with 80 µM of SB-P3G2 and SB-P17G-C2 were visualized (Fig. 23).129, 149 The formation of protofilaments was drastically reduced and only numerous tiny aggregates were formed. In addition to inhibiting the assembly of Mtb-FtsZ in the presence of GTP, SB-P17G-C2 was also able to disrupt the formed FtsZ polymers and aggregates as shown by image E.149 Mtb-FtsZ (5 µM) was polymerized by adding GTP (25 µM) and then treated with 80 µM of SB-P17G-C2. The polymerized protein was depolymerized (and disassembled) after the addition of compound. The results clearly highlight the efficient inhibition of Mtb-FtsZ assembly by lead benzimidazoles, which also exhibit their ability to induce depolymerization of FtsZ protofilaments.

Figure 23.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Images of FtsZ. FtsZ (5 µM) was polymerized by GTP (25 µM) in the absence (A, D) and presence of 80 µM of SB-P3G2 (B) and SB-P17G-C2 (C). Image E displays the effect of SB-P17G-C2 (80 µM) on preformed polymers, wherein FtsZ polymers formed after addition of GTP were treated with compound. Images are at 49,000× magnification (scale bar 500 nm).

In addition to in vitro studies against Mtb-FtsZ, SB-P3G2 and SB-P8B2, two representative compounds, were tested in cell based assays and found to be bactericidal. They were active against non-replicating Mtb grown under low oxygen conditions: 71% and 59% growth inhibition, respectively, at 4 µg/mL dose.149 The latter result is particularly exciting since it indicates that these compounds have potential to be effective against latent TB infection.

Furthermore, SB-P3G2 and SB-P17G-A20 exhibited efficacy in vivo in the standard acute infection model using immune incompetent GKO mice, i.e., SB-P3G2 reduced the bacterial load by 0.71 log10 CFU in the lungs and 0.41 log10 CFU in spleen.151 SB-P17G-A20 reduced the bacterial load in the lung and spleen by 1.73 ± 0.24 log10 CFU and 2.68 ± 0.48 log10 CFU, respectively (>0.28 log10 CFU reduction is considered significant).152

3.3. FtsZ inhibitors for other bacterial strains

Drug discovery efforts on FtsZ as the target have also been made against pathogens other than Mtb, especially MRSA and VRE. Novel compounds targeting virulent bacterial strains such as MRSA, VRE, MSSA, VRE and VSA are summarized in Tables 6. At present, PC190723 is a promising lead compound for MRSA although it possesses suboptimal absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties.153 PC190723 showed efficacy via a single administration (IP or SC), but no efficacy was observed via oral administration.153 A few natural products such as chrysophaentins A154, dichamanetin155 etc. have also been identified to inhibit S. aureus FtsZ. Recently, a series of heteroyclic analogues of sanguinarine and berberine have been synthesized and studied, including benzo[c]phenanthridines, dibenzo[a,g]quinoliziniums, and guanidinomethyl compounds, which inhibited MRSA- and VRE-FtsZ.156–161

Table 6.

FtsZ inhibitors for bacteria other than M. tuberculosis

| Compound | Mode of action |

|---|---|

| Viriditoxin162 | Inhibits GTPase activity and FtsZ polymerization |

| GAL Analogues163 | Inhibits GTPase activity |

| (±)-Dichamanetin155 and (±)-2’’’-Hydroxy-5’’-benzylisouvarinol-B155 | Inhibits GTPase activity |

| PC190723120, 153 PC58538 and PC170942164 | Inhibition of GTPase activity, mislocalization of Z-ring. |

| Chrysophaentins A154 | Inhibition of GTPase activity |

| {1-((4′-(tert-butyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)methyl)guanidine}156 | Enhancement of FtsZ polymerization |

| 5-methylbenzo[c]phenanthridinium derivatives159 and similar compounds157–161 | Inhibition of GTPase activity and FtsZ polymer stabilizers |

4. Conclusion

Cell division or cytokinesis has proven to be an excellent target for drug discovery and development for both anticancer agents and antibacterial agents, as described above. Microtubule/tubulin has been a highly significant molecular target for anticancer agents, including microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs) such as taxanes, epothilones, discodermolide, laulimalide, and zampanolide, as well as microtubule-destabilizing agents such as vinca alkaolids. However, various resistances to those drugs and drug candidates, caused by MDR, point mutations, and overexpression of tubulin subtypes, present serious issues in chemotherapy.

We have been developing new-generation taxoids, which successfully obviate drug resistances common to the first-generation taxane drugs, i.e., paclitaxel and docetaxel. These new-generation taxoids promote instantaneous rapid polymerization of tubulin, forming very short and numerous microtubules, which makes a sharp contrast to paclitaxel. Also, the marked tendency of new-generation taxoids to induce polymerization of tubulin into sheets and other aberrant microtubule-like forms suggests that the novel taxanes induce conformational changes in tubulin that differ significantly from the conformational changes induced by paclitaxel. These differences in their interactions with tubulin and microtubules may play a direct role in their enhanced cytotoxic potency and antitumor efficacy.

The elucidation and analysis of the bioactive structures of MSAs has spurred significant interests for structural and computational biology research in the hope of paving the way for rational drug design of novel and potent MSAs with simplified structures.88 However, this has been quite challenging, mainly due to insufficient resolution in the drug-bound microtubule structures determined by cryo-EM.65, 78, 88 Nevertheless, recent breakthrough in elucidating X-ray crystal structure of drug-bound microtubules would revive this approach.4 In addition, a common pharmacophore approach165 to the drug design for hybrids and novel MSAs has also been revived166 based on the accurate structural information acquired by NMR analysis of drug-bound microtubules in solution phase.167 Accordingly, microtubule/tubulin will continue to be a significant molecular target for next-generation anticancer agents, targeting cell division.

Emergence of drug resistance to existing antibacterial drugs is a serious threat to human health worldwide. The vast majority of currently used antibacterial drugs target cell wall biosynthesis, nucleic acid synthesis and protein synthesis. There is an urgent need to identify a novel drug target that is essential for the bacterial survival to circumvent such drug resistance. In the last decade, FtsZ, an essential bacterial cytokinesis protein and a homologue of tubulin, has emerged as a highly promising new molecular target for the discovery of novel antibacterial agents. Although drug development based on this new target is still in an early stage, FtsZ has already been proven an excellent target for drug discovery. Several classes of compounds have been found effective against various pathogens, including Mtb, MRSA and VRE. FtsZ is a highly conserved and ubiquitous bacterial protein, playing a vital role in bacterial cytokinesis. Thus, the inhibition of proper FtsZ assembly causes the disruption of septum formation and bacterial cell division, leading to cell death. Thus, FtsZ inhibitors are actively investigated for broad-spectrum or pathogen-specific antibacterial drug discovery. Impressive amounts of findings have been accumulated for FtsZ structures and functions based on structural biology as well as cell and microbiology research, which can be translated into structure-based or fragment-based drug discovery.

We correctly envisioned that (i) the disruption of Z-ring formation, either by stabilizing or destabilizing FtsZ polymers would lead to bacterial cell death and (ii) since FtsZ is a totally new target for antibacterial agents, the FtsZ-interacting agents should not have any resistance to the drug-resistant strains for clinically used antibacterial drugs at present. Since it is critical to identify a novel drug target that is essential for the bacterial survival to circumvent drug-resistance, especially to common antitubercular drugs, the selection of Mtb-FtsZ as the novel molecular target was quite significant. We have found that certain taxanes inhibit Z-ring formation by stabilizing FtsZ polymers. C-seco-taxanes exhibit excellent specificity to Mtb-FtsZ and are non-cytotoxic. These novel taxanes are highly effective against MDR-Mtb strains with the same as or even better MIC than that for drug sensitive H37Rv strain. We also have found that novel 2,5,6- and 2,5,7-trisubstituted benzimidazoles inhibit the nucleation/aggregation/polymerization of Mtb-FtsZ quite effectively in a dose-dependent manner, by enhancing the GTPase activity of Mtb-FtsZ. Several lead compounds have been identified, which show highly promising efficacy in the acute animal models as well as ADME profiles in the preclinical drug development.

Judging from the fact that this field of research is experiencing increasing interest and rapid advancement, it is likely that a good number of clinical candidates targeting FtsZ, as next-generation antibacterial agents, will emerge in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the grant support from the National Institutes of Health (GM42798 and CA103314 to I.O. for their work on microtubules and AI078251 to I.O. for their work on FtsZ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Altmann KH. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:424. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ojima I, Vite GD, Altmann K-H. Anticancer Agents: Frontiers in Cancer Chemotherapy, ACS Symp. Series 796. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller JH, Singh AJ, Northcote PT. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:1059. doi: 10.3390/md8041059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prota1 AE, Bargsten K, D Z, Field JJ, Díaz JF, K-H A, Steinmetz MO. Science. 2013;339:587. doi: 10.1126/science.1230582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ojima I, Slater JC, Michaud E, Kuduk SD, Bounaud P-Y, Vrignaud P, Bissery MC, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:3889. doi: 10.1021/jm9604080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ojima I, Slater JC, Kuduk SD, Takeuchi CS, Gimi RH, Sun CM, Park YH, Pera P, Veith JM, Bernacki RJ. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:267. doi: 10.1021/jm960563e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojima I, Wang T, Miller ML, Lin S, Borella C, Geng X, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:3423. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojima I, Chen J, Sun L, Borella CP, Wang W, Miller ML, Lin S, Geng X, Kuznetsova L, Qu C, Gallager D, Zhao X, Zanardi I, Xia S, Horwitz SB, Mallen-St. Clair J, Guerriero JL, Bar-Sagi D, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:3203. doi: 10.1021/jm800086e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojima I, Das M. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:554. doi: 10.1021/np8006556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuznetsova LV, Pepe A, Ungureanu IM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ, Ojima I. J. Fluor. Chem. 2008;129:817. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuznetsova LV, Sun L, Chen J, Zhao X, Seitz J, Das M, Li Y, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ, Xia S, Horwitz SB, Ojima I. J. Fluor. Chem. 2012;143:177. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R. Cell (Cambridge, MA, United States) 2002;109:257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goehring NW, Beckwith J. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:R514. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung AKW, White EL, Ross LJ, Reynolds RC, DeVito JA, Borhani DW. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:953. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moller-Jensen J, Loewe J. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanedar S, Margolin W. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowinsky EK. Ann. Rev. Med. 1997;48:353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suffness M. Taxol: Science and Applications. New York: CRC Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Nature. 1979;277:665. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiff PB, Horwitz SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1980;77:1561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojima I, Duclos O, Kuduk SD, Sun C-M, Slater JC, Lavelle F, Veith JM, Bernacki RJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:2631. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojima I, Duclos O, Zucco M, Bissery M-C, Combeau C, Vrignaud P, Riou JF, Lavelle F. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2602. doi: 10.1021/jm00042a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ojima I, Fenoglio I, Park YH, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:1571. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolaou KC, Yang Z, Liu JJ, Ueno H, Nantermet PG, Guy RK, Claiborne CF, Renaud J, Couladouros EA, Paulvannan K, Sorensen EJ. Nature. 1994;367:630. doi: 10.1038/367630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datta A, Aubé J, Georg GI, Mitscher LA, Jayasinghe LR. BioMed. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:1831. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georg GI, Cheruvallath ZS, Himes RH, Mejillano MR, Burke CT. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:4230. doi: 10.1021/jm00100a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georg GI, Cheruvallath ZS, Himes RH, Mejillano MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992;2:1751. doi: 10.1021/jm00100a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ojima I, Lin S, Wang T. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingston DGI, Chaudhary AG, Chordia MD, Gharpure M, Gunatilaka AAL, Higgs PI, Rimoldi JM, Samala L, Jagtap PG, Jiang YQ, Lin CM, Hamel E, Long BH, Fairchild CR, Johnston KA. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3715. doi: 10.1021/jm980229d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojima I, Slater JC, Michaud E, Kuduk SD, Bounaud P-Y, Vrignaud P, Bissery M-C, Veith J, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:3889. doi: 10.1021/jm9604080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojima I, Slater JS, Kuduk SD, Takeuchi CS, Gimi RH, Sun C-M, Park YH, Pera P, Veith JM, Bernacki RJ. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:267. doi: 10.1021/jm960563e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beer M, Lenaz L, Amadori D. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1066. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ojima I, Slater JC, Pera P, Veith JM, Abouabdellah A, Bégué J-P, Bernacki RJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997;7:209. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojima I, Slater JC. Chirality. 1997;9:487. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1997)9:5/6<487::AID-CHIR15>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojima I, Inoue T, Chakravarty S. J. Fluorine Chem. 1999;97:3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojima I, Lin S, Slater JC, Wang T, Pera P, Bernacki RJ, Ferlini C, G S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000;8:1576. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ojima I. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2004;5:628. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuznetsova LV, Ungureanu IM, Pepe A, Zanardi I, Wu X, Ojima I. J. Fluor. Chem. 2004;125:487. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pepe A, Sun L, Zanardi I, Wu X, Ferlini C, Fontana G, Bombardelli E, Ojima I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:3300. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunasekera SP, Gunasekera M, Longley RE, Schulte GK. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4912. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunasekera SP, Gunasekera M, Longley RE, Schulte GK. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:1346. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ter Haar E, Kowalski RJ, Hamel E, Lin CM, Longley RE, Gunasekera SP, Rosenkranz HS, Day BW. Biochemistry. 1996;35:243. doi: 10.1021/bi9515127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein LE, Freeze BS, Smith III AB, Horwitz SB. Cell Cycle. 2005;41:501. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicoletti MI, Colombo T, Rossi C, Monardo C, Stura S, Zucchetti M, Riva A, Morazzoni P, Donati MB, Bombardelli E, D'Incalici M, Giavazzi R. Cancer Res. 2000;60:842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vredenburg MR, Ojima I, Veith J, Pera P, Kee K, Cabral F, Sharma A, Kanter P, Bernacki RJ. J. Nat'l. Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1234. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.16.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan MA, Ojima I, Rosas F, Distefano M, Wilson L, Scambia G, Ferlini G. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vobořilová J, Němcová-Fürstová V, Neubauerová J, Ojima I, Zanardi I, Gut I, Kovář J. Invest. New Drugs. 2012;30:991. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:48. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dumontet C, Sikic BI. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:1061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cabral F, Wible L, Brenner S, Brinkley BR. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schibler MJ, Cabral F. J. Cell Biol. 1986;102:1522. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu Q, Luduena RF. Cell Struct. Funct. 1993;18:173. doi: 10.1247/csf.18.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haber M, Burkhart CA, Regl DL, Madafiglio J, Norris MD, Horwitz SB. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:31269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giannakakou P, Sackett DL, Kang Y-K, Zhan Z, Buters JTM, Fojo T, Poruchynsky MS. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kavallaris M, Kuo D-S, Burkhart CA, Regl DL, Norris MD, Haber M, Horwitz SB. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1282. doi: 10.1172/JCI119642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banerjee A, Roach MC, Trcka P, Luduena RF. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:5625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Panda D, Miller HP, Banerjee A, Luduena RF, Wilson L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sullivan KF. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1988;4:687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banerjee A, Luduena RF. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma J, Luduena RF. J. Prot. Chem. 1994;13:165. doi: 10.1007/BF01891975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwarz PM, Liggins JR, Luduena RF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4687. doi: 10.1021/bi972763d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derry WB, Wilson S, Khan IA, Luduena RF, Jordan MA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3554. doi: 10.1021/bi962724m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferlini C, Raspaglio G, Mozzetti S, Cicchillitti L, Filippetti F, Gallo D, Fattorusso C, Campiani G, Scambia G. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2397. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Magnani M, Ortuso F, Soro S, Alcaro S, Tramontano A, Botta M. FEBS J. 2006;273:3301. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Löwe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:1045. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Barasoain I, Matesanz R, Diaz JF, Fang W-S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:751. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barasoain I, Garcıa-Carril AM, Matesanz R, Maccari G, Trigili C, Mori M, Shi J-Z, Fang W-S, Andreu JM, Botta M, Dıaz JF. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:243. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen S, Zhao X, Chen J, Chen J, Kuznetsova L, Wong SS, Ojima I. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:979. doi: 10.1021/bc9005656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J, Chen S, Zhao X, Kuznetsova LV, Wong SS, Ojima I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16778. doi: 10.1021/ja805570f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dubois J, Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Guedira N, Potier P, Gillet B, Beloeil JC. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:6533. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams HJ, Scott AI, Dieden RA, Swindell CS, Chirlian LE, Francl MM, Heerding JM, Krauss NE. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:6545. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vander Velde DG, Georg GI, Grunewald GL, Gunn CW, Mitscher LA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:11650. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mastropaolo D, Camerman A, Luo Y, Brayer GD, Camerman N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ojima I, Kuduk SD, Chakravarty S, Ourevitch M, Begue J-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5519. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kingston DGI, Bane S, Snyder JP. Cell cycle. 2005;4:279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ojima I, Lin S, Inoue T, Miller ML, Borella CP, Geng X, Walsh JJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5343. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geng X, Miller ML, Lin S, Ojima I. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3733. doi: 10.1021/ol0354627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Nature. 1998;391:199. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lowe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. J. Mol. Bol. 2001;313:1045. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Snyder JP, Nettles JH, Cornett B, Downing KH, Nogales E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051309398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ganesh T, Guza RC, Bane S, Ravindra R, Shanker N, Lakdawala AS, Snyder JP, Kingston DGI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403459101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Querolle ODJ, Thoret S, Roussi F, Gueritte F, Guénard D. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5937. doi: 10.1021/jm0497996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ganesh T, Yang C, Norris A, Glass T, Bane S, Ravindra R, Banerjee A, Metaferia B, Thomas SL, Giannakakou P, Alcaraz AA, Lakdawala AS, Snyder JP, Kingston DGI. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:713. doi: 10.1021/jm061071x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Larroque A-L, Dubois J, Thoret S, Aubert G, Chiaroni A, Gueritte F, Guenard D. Bioorg. Med.Chem. 2007;15:563. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li Y, Poliks B, Cegelski L, Poliks M, Cryczynski A, Piszcek G, Jagtap PG, Studelska DR, Kingston DGI, Schaefer J, Bane S. Biochemistry. 2000;39:281. doi: 10.1021/bi991936r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rao S, He L, Chakravarty S, Ojima I, Orr GA, Horwitz SB. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Geney R, Sun L, Pera P, Bernacki Ralph J, Xia S, Horwitz Susan B, Simmerling Carlos L, Ojima I. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:339. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun L, Simmerling C, Ojima I. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:719. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Paik Y, Yang C, Metaferia B, Tang S, Bane S, Ravindra R, Shanker N, Alcaraz AA, Johnson SA, Schaefer J, O'Connor RD, Cegelski L, Snyder JP, Kingston DGI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:361. doi: 10.1021/ja0656604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun L, Geng X, Geney R, Li Y, Li Z, Lauher JW, Xia S, Howtizs SB, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernackic RJ, Ojima I. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:9584. doi: 10.1021/jo801713q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Geney R, Sun L, Pera P, Bernacki RJ, Xia S, Horwitz SB, Simmerling CL, Ojima I. Chem. & Biol. 2005;12:339. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Erickson Harold P, Anderson David E, Osawa M. Microbiol Molecul. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:504. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adams DW, Errington J. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:642. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Margolin W. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000;24:531. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen Y, Bjornson K, Redick SD, Erickson HP. Biophys. J. 2005;88:505. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dajkovic A, Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:2513. doi: 10.1128/JB.01612-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. Embo J. 1998;17:462. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Caplan MR, Erickson HP. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:13784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]