Abstract

Background and Purpose

Occlusive radiation vasculopathy (ORV) predisposes head-and-neck cancer survivors to ischemic strokes.

Methods

We analyzed the digital subtraction angiography acquired in 96 patients who had first-ever transient ischemic attack or ischemic strokes attributed to ORV. Another age-matched 115 patients who had no radiotherapy but symptomatic high-grade (>70%) carotid stenoses were enrolled as referent subjects. Digital subtraction angiography was performed within 2 months from stroke onset and delineated carotid and vertebrobasilar circulations from aortic arch up to intracranial branches. Two reviewers blinded to group assignment recorded all vascular lesions, collateral status, and infarct pattern.

Results

ORV patients had less atherosclerotic risk factors at presentation. In referent patients, high-grade stenoses were mostly focal at the proximal internal carotid artery. In contrast, high-grade ORV lesions diffusely involved the common carotid artery and internal carotid artery and were more frequently bilateral (54% versus 22%), tandem (23% versus 10%), associated with complete occlusion in one or both carotid arteries (30% versus 9%), vertebral artery (VA) steno-occlusions (28% versus 16%), and external carotid artery stenosis (19% versus 5%) (all P<0.05). With comparable rates of vascular anomaly, ORV patients showed more established collateral circulations through leptomeningeal arteries, anterior communicating artery, posterior communicating artery, suboccipital/costocervical artery, and retrograde flow in ophthalmic artery. In terms of infarct topography, the frequencies of cortical or subcortical watershed infarcts were similar in both groups.

Conclusions

ORV angiographic features and corresponding collaterals are distinct from atherosclerotic patterns at initial stroke presentation. Clinical decompensation, despite more extensive collateralization, may precipitate stroke in ORV.

Keywords: head-and-neck cancer, ischemic stroke, occlusive radiation vasculopathy

Definitive radiotherapy (RT) is a standard treatment for all subsites of primary head and neck cancers and accounts for a dramatic improvement in the cure rates of patients.1 However, survivors are susceptible to an increased risk of stroke in the long term attributed to occlusive radiation vas-culopathy (ORV).2 In head-and-neck cancer cohorts, stroke risks in patients exceeded risks in comparable healthy populations by 2 to 9 times.3,4 A population-based study of patients aged >65 years revealed an excess risk of cerebrovascular disease after definitive RT of head-and-neck region when compared with patients receiving surgery alone.5

In the acute phase, ORV is characterized by detachment of endothelium, splitting of basement membranes, and subinti-mal foam cell formation. Atherosclerotic-like changes of the medial layer and progressive adventitia fibrosis then follow, leading ultimately to steno-occlusion of irradiated arteries years after the initial RT.6,7 Yet, the stroke pathophysiology and treatment of ORV remained uncertain.

We previously showed that carotid ORV lesions were typically diffuse with intraplaque hypoechoic foci on ultrasonography.8 Our group found greater intima-medial thickness9 and a higher incidence of carotid stenosis in survivors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma that predicted stroke occurrence.10,11 By color velocity imaging technique, we correlated ischemic symptoms of ORV patients with a low cerebral blood flow, suggesting that cerebral hypoperfusion could be an important stroke mechanism.12

Nevertheless, previous ultrasonography-based studies did not evaluate cephalad intracranial tributaries or proximal trunks of carotid and vertebrobasilar arteries. So far, no study has examined the collateral circulation and infarct topography in ORV stroke patients. Understanding the angiographic features, infarct pattern and the resultant alteration in cerebral hemodynamics of ORV may give insight to the stroke mechanism and formulation of rational treatment. We aimed to use digital subtraction angiography to delineate the morphological distinctions and collateral flow patterns of ORV stroke patients.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved the study and each participant provided an informed consent. From September 2005 to July 2012, we approached consecutive adult patients who presented with first-ever transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke attributed to ORV. Each ORV patient had definitive RT for a primary head-and-neck cancer before the stroke onset. Stroke neurologists determined the stroke etiology and relevance to ORV by clinical syndrome and concurrent cardiovascular risks. We excluded patients with atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, autoimmune vasculitis, Takayasu disease, hereditary thrombophilia, active malignancy, prior angioplasty, or surgery that might have injured craniocer-vical arteries (eg, radical neck dissection).

In the referent group, we enrolled age-matched patients who had first-ever transient ischemic attack or ischemic strokes associated with spontaneous atheromatous carotid disease, that is, no prior RT but >70% symptomatic carotid stenosis by ultrasonography. To avoid overstating the sequels of RT, we excluded stroke-related small vessel disease.

We recorded the demographics and risk factors (hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus) of all patients. Each patient underwent computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline. Digital subtraction angiography was performed within 2 months from the qualifying stroke. We obtained the angio-grams by injecting contrast (10 mL of iopamiro 300 diluted in 1:1 with normal saline) at each proximal part of common carotid arteries (CCAs), internal carotid arteries (ICAs), external carotid arteries (ECAs), and subclavian arteries from anteroposterior, lateral, and bilateral oblique views in a biplane, high-resolution angiography system (Philips BV 5000; Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Carotid and vertebrobasilar circulations were imaged from aortic arch up to distal intracranial branches. Each angiographic run captured a complete series of images from arterial phase to late venous phase for collateral evaluation. Additional views were sought to depict the lesions in profile if necessary.

Evaluation of Infarct Pattern, Vascular Lesions, and Collateral Status

A stroke neurologist and a neuroradiologist blind to group assignment reviewed the computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging and cerebral angiograms. The infarct topography and the distribution of stenotic, aneurysmal, ulcerative, and dissecting lesions were recorded. In case of disagreements, the opinion of a third neuroradiologist was sought.

Cerebral infarcts were classified as13 (1) territorial: ≥2 subdivisions of the middle cerebral artery, (2) cortical watershed: cortical border zone between middle cerebral artery and anterior cerebral artery or middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery, (3) other cortical: nonwatershed nonterritorial cortical infarct, (4) deep watershed infarct: rosary-like, confluent, striated, or solitary located in the su-praventricular or paraventricular areas (corona radiata or centrum se-miovale), excluding immediately subcortical lesions, and (5) other deep: large striatocapsular lesions (>15 mm), single perforator (<15 mm). The purpose of distinguishing territorial infarcts from smaller cortical or subcortical infarcts was to evaluate whether collateralization had any effect on the infarct size or topography.

Stenoses were measured by NASCET criteria.14 Disease was bilateral if >50% stenoses were found on both sides of the neck. Lesions were tandem if two or more >50% stenoses were revealed on one side. An ulcer was invagination of contrast beyond the vascular lumen. Diffuse lesions were arteriopathy >15 mm in length. Dissection was an intimal flap extending into the vessel lumen.

For assessment of collateralization, we first identified the potential ischemic regions that were distal to high-grade steno-occlusions. In anterior circulation, these regions were anterior cerebral artery and middle cerebral artery territories ipsilateral to a >70% CCA or ICA stenosis. In posterior circulation, these regions were cerebellum and posterior cerebral artery territories distal to an occluded VA (ie, a singular VA) or bilateral VA were stenosed >50%. We evaluated collateral flow both symptomatic and asymptomatic ischemic regions. All possible sources of collaterals to these potentially ischemic regions were then recorded, which included leptomeningeal arteries, anterior communicating arteries, posterior communicating arteries, and anastomotic regions between extracranial arteries and ICA/VA, ie, orbit, cavernous sinus, middle ear, upper cervical area, costocervical regions, and foramen magnum.

We graded the collateral circulation for each potential ischemic region based on the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology Collateral Flow Grading System.15 This angiographic scale assigned patients to grades 0 (no collaterals visible to the ischemic site), 1 (slow collaterals to the periphery of the ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect), 2 (rapid collaterals to the periphery of ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect and to only a portion of the ischemic territory), 3 (collaterals with slow but complete angiographic blood flow of the ischemic bed by the late venous phase), and 4 (complete and rapid collateral blood flow to the vascular bed in the entire ischemic territory by retrograde perfusion). Anatomic variants that might preclude or mimic collateral flow (eg, incompetence of circle of Willis or persistent trigeminal artery) were documented.16

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed by independent t test and expressed as mean±interquartile range/SD. Categorical variables were analyzed by χ2 test. Inter-rater reliability was measured by Kappa and interclass correlation coefficient for categorical and continuous variables.

Results

From September 2005 to July 2012, a total of 139 patients with prior craniocervical RT were admitted for acute ischemic stroke. Excluding 29 patients for stroke recurrence (n=18), atrial fibrillation (n=3), nonORV stroke etiology (n=5), and prior carotid stenting (n=3), 96 out of the remaining 110 patients consented to digital subtraction angiography. They all received definitive RT by hyperfractionation or accelerated fractionation. Mean radiation dose was 54 Gy (range, 50–60 Gy). The primary sites of malignancy were nasopharynx (n=85), larynx (n=7), and tongue (n=4). No patient received adjuvant thoracic RT. The mean interval between RT and stroke was 15.0 years (interquartile range, 9.8 years).

In the same recruitment period, we enrolled 115 age-matched patients who had no RT but first-ever ischemic strokes associated with >70% carotid stenosis as referent subjects. The carotid stenosis was presumably due to atheromatous disease.

Table 1 summarized the patients’ demographics. ORV patients had less cardiovascular risks in terms of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scales were comparable in both groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients in Case and Referent Groups

| ORV (N=96), % | Reference (N=115), % | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean±SD) | 61.9±10.3 | 63.9±7.0 | 0.119 |

| Men | 77 (80.2) | 87 (75.7) | 0.428 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 48 (50.0) | 97 (84.3) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (56.2) | 89 (77.4) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (12.5) | 46 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| Ever smoking | 51 (53.1) | 58 (50.4) | 0.697 |

| NIHSS (median, IQR) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.098 |

IQR indicates interquartile range; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; and ORV, occlusive radiation vasculopathy.

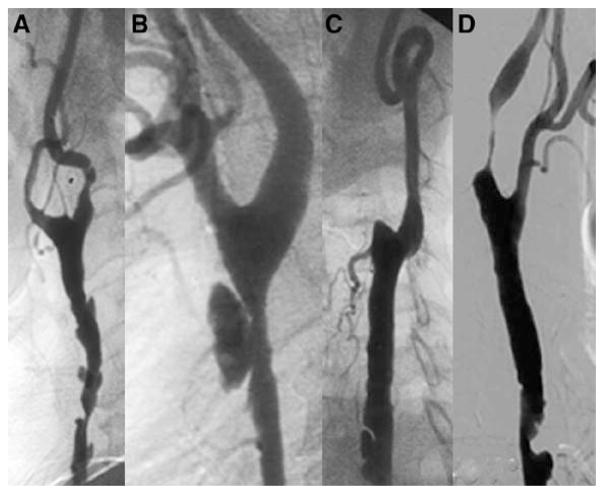

Inter-rater reliability on lesion identification and collateral grading was moderate to excellent (κ/interclass correlation coefficient=0.4–1). Table 2 shows the lesion distribution. In referent patients, high-grade stenoses (>70%) were mostly focal at proximal ICA (122 of 135; 90.4%). In contrast, high-grade ORV lesions diffusely distributed over CCA (72 of 182; 39.6%) and ICA (66 of 182; 36.3%). ORV stenoses were more frequently bilateral (54% versus 22%), tandem (23% versus 9%), associated with complete occlusion of one or bilateral CCA/ICA (30% versus 9%), VA steno-occlusion (27% versus 14%), and ECA steno-occlusion (19% versus 0.9%) (Table 3). ORV patients also had more dissecting and ulcerative lesions (Figure 1), but significantly less intracranial stenosis (1/96 versus 16/115; P<0.001; not shown in table). No aneurysm or moyamoya syndrome patterns were recorded.

Table 2.

Distribution of Stenoses in Extracranial Arteries

| ORV (% of Total Lesions)

|

Reference (% of Total Lesions)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA | ECA | ICA | VA | SubA | Total | CCA | ECA | ICA | VA | SubA | Total | |

| Stenotic severity | ||||||||||||

| 50% to 69% | 34 | 3 | 20 | 8 | 2 | 67 (26.9) | 1 | 2 | 23 | 8 | 4 | 38 (22.0) |

| 70% to 99% | 60 | 6 | 48 | 6 | 4 | 124 (49.8)* | 1 | 0 | 112 | 4 | 3 | 120 (69.4) |

| Complete occlusion | 12 | 13 | 18 | 13 | 2 | 58 (23.3)* | 0 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 15 (8.6) |

| 106 (42.6)* | 22 (8.8)* | 84 (34.5)* | 27 (10.9) | 8 (3.2) | 249 (100)* | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.7) | 145 (83.8) | 16 (9.2) | 7 (4.0) | 173 (100) | |

CCA indicates common carotid artery; ECA, external carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; ORV, occlusive radiation vasculopathy; SubA, subclavian artery; and VA, vertebral artery.

P<0·05.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Lesions and Infarct Pattern

| ORV (N=96) | Reference (N=115) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Patient no., % | |||

| Ulcers | 66 (69.8) | 30 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Dissections | 19 (19.8) | 3 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Bilateral >50% CCA/ICA stenoses | 52 (54.2) | 25 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Bilateral 70% to 99% CCA/ICA stenoses | 17 (17.7) | 7 (6.0) | 0.008 |

| Total occlusion in one or both CCA/ICA | 29 (30.2) | 10 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Tandem stenoses in CCA/ICA | 22 (22.9) | 10 (8.7) | 0.004 |

| Diffuse lesions (>15 mm) | 85 (88.5) | 57 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Intracranial stenosis (>50%) | 3 (3.1) | 24 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| VA steno-occlusion (>50%) | 26 (27.1) | 16 (13.9) | 0.017 |

| ECA steno-occlusion (>70%) | 18 (18.8) | 1 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| No. of patients with infarcts in CT/MRI | 85 | 109 | |

| Total no. of infarcts identified | 118 | 168 | |

| Supratentorial infarct (% of total infarcts) | 98 (83.1) | 141 (83.9) | 0.844 |

| Territorial infarcts | 5 (4.2) | 19 (11.3) | 0.034 |

| Cortical watershed infarcts | 14 (11.9) | 21 (12.5) | 0.872 |

| Other cortical infarcts | 11 (9.3) | 11 (6.5) | 0.386 |

| Deep watershed infarcts | 29 (24.6) | 39 (23.2) | 0.790 |

| Other deep infarcts | 39 (33.1) | 51 (30.4) | 0.629 |

| Infratentorial infarct (% of total infarcts) | 20 (16.9) | 27 (16.1) | 0.844 |

| Brain stem | 15 (12.7) | 19 (11.3) | 0.718 |

| Cerebellum | 5 (4.2) | 8 (4.8) | 0.834 |

| Cortical | 4 | 5 | |

| Subcortical | 1 | 3 | |

CCA indicates common carotid artery; CT, computed tomography; ECA, external carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ORV, occlusive radiation vasculopathy; and VA, vertebral artery.

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics of occlusive radiation vasculopathy. A, Diffuse lesion in common carotid artery; B, ulcerative stenosis with a thin ruptured cap; C, occluded external carotid artery and a dissecting flap in common carotid artery; and D, tandem stenoses.

In terms of infarct pattern, ORV patients have less territorial infarcts (4% versus 11%). Yet, we could not find any association between collateralization and infarct size/topography when we compared the collateral pattern in patients with territorial infarcts versus small cortical or subcortical infarcts. The frequencies of cortical or subcortical watershed infarcts were similar in both groups (Table 3).

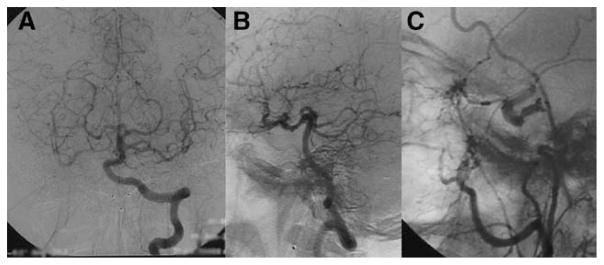

The rates of vascular anomaly at the circle of Willis were comparable in both groups (Table 4). We identified 141 potential ischemic regions in ORV group (anterior circula-tion=128; posterior circulation=13) and 134 in the referent group (anterior circulation=128; posterior circulation=6). We observed 6 major collateral pathways to these potential ischemic regions (Table 4); and among them, ORV patients showed significantly more collateral circulations through (1) anterior communicating artery to contralateral anterior cerebral artery/middle cerebral artery territory, (2) leptomeningeal arteries from posterior cerebral artery to ipsilateral middle cerebral artery territory, (3) posterior communicating artery from ICA to ipsilateral posterior cerebral artery territory, (4) costocervical and suboccipital branches to ipsilateral VA, and (5) ophthalmic artery from ECA to ipsilateral ICA tributaries (Figure 2). The majority of collaterals (70%) in ORV patients were grade 2 or above.

Table 4.

Collateral Statuses of Study Patients

| ORV (N=96) | Reference (N=115) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Patient no. (%) | |||

| Vascular anomaly | |||

| Absent ACom artery* | 19 (19.8) | 36 (31.3) | 0.058 |

| Absent ACA A1 segment* | 9 (9.4) | 21 (18.3) | 0.066 |

| Absent PCom artery* | |||

| One side | 39 (40.6) | 58 (50.4) | 0.155 |

| Both sides | 27 (28.1) | 22 (19.1) | 0.123 |

| Persistent trigeminal artery (fetal origin of PCA) | 21 (21.9) | 21 (18.3) | 0.513 |

| Major sources of collaterals to ischemic territories | |||

| Through ACom artery to contralateral ACA/MCA territory | 77 (80.2) | 76 (66.1) | 0.022 |

| Through leptomeningeal artery from PCA to ipsilateral MCA territory | 48 (50.0) | 30 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Through PCom artery from PCA to ipsilateral MCA territory | 56 (58.3) | 66 (57.4) | 0.890 |

| Through PCom artery from ICA to ipsilateral PCA territory | 10 (10.4) | 4 (3.5) | 0.044 |

| Retrograde flow in ophthalmic artery | 43 (44.3) | 22 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| Suboccipital and costocervical trunks to ipsilateral VA territory | 47 (49.0) | 39 (33.9) | 0.027 |

| Collateral grading of ischemic territories | N=141, % | N=134, % | |

| 0 | 12 (8.5) | 13 (9.7) | |

| 1 | 30 (21.3) | 42 (31.3) | |

| 2 | 57 (40.4) | 52 (38.8) | |

| 3 | 24 (17.0) | 18 (13.5) | |

| 4 | 18 (12.8) | 9 (6.7) | |

ACA indicates anterior cerebral artery; ACom artery, anterior communicating artery; CCA, common carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ORV, occlusive radiation vasculopathy; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; PCom artery, posterior communicating artery; and VA, vertebral artery.

Diagnosis by absence in angiograms.

Figure 2.

Collateralization in a patient with both internal carotid arteries occluded. In left vertebral artery angiogram, robust collaterals to both cerebral hemispheres were evident through posterior communicating arteries (A [frontal] and B [lateral] views). Retrograde flow in ophthalmic artery outlined the carotid siphon in external carotid artery angiogram (C).

Discussion

In this hospital-based case-referent study, we found two major angiographic distinctions between ORV and spontaneous atheromatous carotid disease. First, ORV patients had more tandem, bilateral steno-occlusions involving the CCA and ICA that were associated with VA and ECA stenosis. Second, ORV patients showed significantly more extensive collateral circulation at their first stroke presentation. In terms of infarct topography, ORV patients have less territorial infarcts. However, the frequencies of subcortical or watershed infarcts were similar in both groups.

Definitive RT for carcinomas of pharynx, larynx, and oral cavity typically covered both sides of the neck for probable local regional disease. The spatial distribution of ORV corresponded to the radiation field. Apparently, the differential involvement of carotid versus vertebrobasilar circulation was less obvious than proposed.17 Instead, steno-occlusion of VA ostium was common. Interestingly, no moyamoya disease-like vasculopathy18 was found in arteries adjacent to temporal lobes where radiation-induced necrosis was frequent.

ORV was once coined accelerated atherosclerosis, but we found a lower prevalence of atherosclerotic risks in ORV group. Concordantly, intracranial stenosis, a common manifestation of atherosclerosis in Asians, was also rare in the ORV group. These findings suggest that pathology other than atherosclerosis might prevail; and in fact, some histological features, such as thickening of endothelium, vasa vasorum occlusion, and periadventitial fibrosis, were unique for ORV and absent in atherosclerotic plaque.2 Involvement of the vasa vasorum may predispose to the diffuse pattern of proximal arterial disease noted in our analyses.

We found more established collaterals in ORV patients; and the majority of these collaterals (70%) were grade 2 or above. Anatomic variants were unlikely to explain the disparity, as the rates of circle of Willis incompetence and persistent trigeminal artery were comparable in both groups. The relative paucity of collaterals in referent patients suggested that some collateral circulations in ORV patients might have developed before stroke and had a protective role in delaying the onset of stroke symptoms. The mature collaterals on the side of asymptomatic ORV stenosis supported this notion. It is plausible that dormant anastomoses assumed a greater hemodynamic role in the early phase of ORV to compensate for a restriction of flow. Despite more robust collateralization, subsequent compromise of these collaterals at a later time point may occur when steno-occlusions have extensively involved the proximal trunks of the CCA and VA. Moreover, tandem stenoses impeded blood flow more than a single stenosis of comparable luminal narrowing.19 Diffuse patterns of ORV, possibly because of vasa vasorum occlusion, may result in longer stenoses that cause a greater decrement in downstream blood flow. Although collaterals may initially compensate for such hypoperfusion, more advanced or later stages of ORV may lead to stroke owing to collateral decompensation.20 This hypothesis is consistent with our previous finding that ischemic symptoms of ORV correlated with a low cerebral blood flow measured by color velocity imaging technique.11 Interestingly, although ECA stenosis was common, ORV patients frequently derived collateral flow from ECA through ophthalmic artery. This might suggest the potential benefit of ECA angioplasty in patients with total ICA occlusion(s) or retinal ischemic symptoms. However, such a procedure may pose a risk of embolization to the eye if the flow in ophthalmic artery is retrograde.

In terms of infarct pattern, ORV patients have less territorial infarcts compared with referent patients (P=0.034). However, in further analysis among ORV patients, we could not find any association between collateralization and infarct size, possibly related to a small number of patients with territorial infarcts (n=5). The comparable frequencies of cortical or subcortical watershed infarcts in both groups reinforced the view that infarctions at borderzone might not pinpoint a specific etiology and could result from hemodynamic, embolic, or other stroke mechanisms.21,22 Indeed, identification of stroke patho-physiology based on topography of vascular territory lesions alone could be difficult when individual arterial territories could not be recognized in vivo.23

The relatively favorable prognosis in head-and-neck cancer makes late complications of RT an important concern in regions where these tumors are endemic.24 However, no study so far has described the collateral or infarct pattern of ORV. Current major stroke guidelines offer no recommendation on strokes attributed to ORV.25,26 It is controversial if treatment of ORV should follow other stroke subtypes. One concern, for instance, is precipitation of ischemic symptoms on blood pressure lowering in patients with marginal cerebral perfusion. In fact, if ORV is primarily not an atherosclerotic disorder, risk factor modification and control would unlikely halt progression. Alternatively, strategies that can augment collateral perfusion or improve steno-occlusions may play a role in preventing ORV strokes.

Our study had a few limitations. First, although ORV patients had less cardiovascular risks, atherosclerosis might still confound the arteriopathy. Second, the relatively homogeneous cancer types and mode of RT may limit the interpretation of our study because portal field and radiation dose may differ in treatment of other head-and-neck cancers. Third, referent patients were physically fit for intervention because digital subtraction angiography was regarded as a preopera-tive evaluation. The exclusion of unfit patients, though was ethically sound, might generate a selection bias. Finally, a longitudinal study is needed to delineate progression of ORV and clarify whether patients devoid of functional collateral channels may develop stroke earlier.

Conclusions

ORV patients had more steno-occlusions over carotid and vertebral arteries amid mature collateral circulation at initial stroke presentation. Decompensation of collateral flows may precipitate stroke in ORV.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

The study was supported by S.H. Ho Foundation, Vascular and Interventional Radiology Foundation, and Research Grant Council, Hong Kong (Ref 470411).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Cognetti DM, Weber RS, Lai SY. Head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1911–1932. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plummer C, Henderson RD, O’Sullivan JD, Read SJ. Ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack after head and neck radiotherapy: a review. Stroke. 2011;42:2410–2418. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.615203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes JC, Machtay M, Weber RS, Weinstein GS, Chalian AA, Rosenthal DI. Relative risk of stroke in head and neck carcinoma patients treated with external cervical irradiation. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1883–1887. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200210000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorresteijn LD, Kappelle AC, Boogerd W, Klokman WJ, Balm AJ, Keus RB, et al. Increased risk of ischemic stroke after radiotherapy on the neck in patients younger than 60 years. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:282–288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GL, Smith BD, Buchholz TA, Giordano SH, Garden AS, Woodward WA, et al. Cerebrovascular disease risk in older head and neck cancer patients after radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5119–5125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halak M, Fajer S, Ben-Meir H, Loberman Z, Weller B, Karmeli R. Neck irradiation: a risk factor for occlusive carotid artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:299–302. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murros KE, Toole JF. The effect of radiation on carotid arteries. A review article. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:449–455. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520400109029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam WW, Liu KH, Leung SF, Wong KS, So NM, Yuen HY, et al. Sonographic characterisation of radiation-induced carotid artery stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:168–173. doi: 10.1159/000047771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.So NM, Lam WW, Chook P, Woo KS, Liu KH, Leung SF, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in patients with head and neck irradiation for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:600–603. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuen HY, Wong KS, Liu KH, Metreweli C. Incidence of Carotid stenosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2001;23:780–784. doi: 10.1002/hed.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam WW, Leung SF, So NM, Wong KS, Liu KH, Ku PK, et al. Incidence of carotid stenosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients after radiother-apy. Cancer. 2001;92:2357–2363. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2357::aid-cncr1583>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam WW, Ho SS, Leung SF, Wong KS, Metreweli C. Cerebral blood flow measurement by color velocity imaging in radiation-induced carotid stenosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:1055–1060. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.10.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momjian-Mayor I, Baron JC. The pathophysiology of watershed infarction in internal carotid artery disease: review of cerebral perfusion studies. Stroke. 2005;36:567–577. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155727.82242.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with highgrade carotid stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, Tomsick T, Connors B, Barr J, et al. Technology Assessment Committee of the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology; Technology Assessment Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:e109–e137. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Raamt AF, Mali WP, van Laar PJ, van der Graaf Y. The fetal variant of the circle of Willis and its influence on the cerebral collateral circulation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:217–224. doi: 10.1159/000094007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omura M, Aida N, Sekido K, Kakehi M, Matsubara S. Large intracranial vessel occlusive vasculopathy after radiation therapy in children: clinical features and usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)82497-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullrich NJ, Robertson R, Kinnamon DD, Scott RM, Kieran MW, Turner CD, et al. Moyamoya following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors in children. Neurology. 2007;68:932–938. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257095.33125.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guppy KH, Charbel FT, Loth F, Ausman JI. Hemodynamics of in-tandem stenosis of the internal carotid artery: when is carotid endarterec-tomy indicated? Surg Neurol. 2000;54:145–52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00292-5. discussion 152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caplan LR, Wong KS, Gao S, Hennerici MG. Is hypoperfusion an important cause of strokes? If so, how? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:145–153. doi: 10.1159/000090791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moustafa RR, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Jones PS, Graves MJ, Fryer TD, Gillard JH, et al. Watershed infarcts in transient ischemic attack/minor stroke with > or = 50% carotid stenosis: hemodynamic or embolic? Stroke. 2010;41:1410–1416. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung TW, Yip SF, Lam CW, Chan TL, Lam WW, Siu DY, et al. Genetic predisposition of white matter infarction with protein S deficiency and R355C mutation. Neurology. 2010;75:2185–2189. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennerici M, Daffertshofer M, Jakobs L. Failure to identify cerebral infarct mechanisms from topography of vascular territory lesions. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1067–1074. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu MC, Yuan JM. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x02000858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, Albers GW, Bush RL, Fagan SC, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Stroke Organization (ESO) Executive Committee, ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for stroke management. updated January 2009. http://www.eso-stroke.org/pdf/ESO%20Guidelines_update_Jan_2009.pdf.