Significance

Group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 (GIVA cPLA2) is widely viewed as the primary enzyme responsible for inflammatory arachidonic acid (AA) release and with high specificity. Our results demonstrate dual, phase-specific release of AA and 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic (15-HETE) acid by GIVA cPLA2 in primary and immortalized macrophages during a receptor-mediated program required for complete inflammatory commitment. These dual actions by GIVA cPLA2 were necessary for biosynthesis of proresolving lipoxins, providing a unique, upstream example of an enzyme linked to both the initiation and resolution of inflammation. Further, our results demonstrate a single-cell mechanism of lipoxin synthesis that is more efficient than the established transcellular biosynthetic mechanisms, underscoring the importance of enzyme coupling and the possibility of proresolution therapies at the membrane level.

Keywords: lipidomics, enzyme coupling, membrane remodeling

Abstract

Initiation and resolution of inflammation are considered to be tightly connected processes. Lipoxins (LX) are proresolution lipid mediators that inhibit phlogistic neutrophil recruitment and promote wound-healing macrophage recruitment in humans via potent and specific signaling through the LXA4 receptor (ALX). One model of lipoxin biosynthesis involves sequential metabolism of arachidonic acid by two cell types expressing a combined transcellular metabolon. It is currently unclear how lipoxins are efficiently formed from precursors or if they are directly generated after receptor-mediated inflammatory commitment. Here, we provide evidence for a pathway by which lipoxins are generated in macrophages as a consequence of sequential activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a receptor for endotoxin, and P2X7, a purinergic receptor for extracellular ATP. Initial activation of TLR4 results in accumulation of the cyclooxygenase-2–derived lipoxin precursor 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) in esterified form within membrane phospholipids, which can be enhanced by aspirin (ASA) treatment. Subsequent activation of P2X7 results in efficient hydrolysis of 15-HETE from membrane phospholipids by group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2, and its conversion to bioactive lipoxins by 5-lipoxygenase. Our results demonstrate how a single immune cell can store a proresolving lipid precursor and then release it for bioactive maturation and secretion, conceptually similar to the production and inflammasome-dependent maturation of the proinflammatory IL-1 family cytokines. These findings provide evidence for receptor-specific and combinatorial control of pro- and anti-inflammatory eicosanoid biosynthesis, and potential avenues to modulate inflammatory indices without inhibiting downstream eicosanoid pathways.

A complex network of danger-sensing receptors and bioactive peptide and lipid signals, including cytokines and eicosanoids, regulates innate immunity. Toll-like receptor (TLR) priming is suggested as a precautionary step in building a significant inflammatory response by driving production of IL-1 family protokines, which remain inactive until a second stimulus drives them to bioactive maturation and secretion (1). The second step of this process has been most strongly linked to extracellular ATP and specifically to one of its purinergic receptors, P2X7 (2, 3), particularly in macrophages (4).

TLR stimulations also increase prostaglandin synthesis by activating cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) through a Ca2+-independent mechanism to release arachidonic acid (AA) from phospholipids, and by increasing expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1. P2X7 stimulation activates cPLA2 through a Ca2+-dependent mechanism that couples AA metabolism with 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX)-activating protein (FLAP), Ca2+-activated 5-LOX, and constitutive COX-1 to form leukotrienes (LTs) and prostaglandins (PGs). Short-term (∼1 h) TLR priming of Ca2+ ionophore/P2X7-activated immune cells enhances LT synthesis (5, 6), but long-term TLR priming (16–18 h) significantly suppresses LT synthesis by different cell-type–specific mechanisms (7, 8).

Whereas PGE2, PGI2, and LTC4 promote local edema from postcapillary venules, and LTB4 amplifies neutrophil recruitment to initiate pathogenic killing, subsequent “class switching” to lipoxin (LX) formation by “reprogrammed” neutrophils inhibits additional neutrophil recruitment during self-resolving inflammatory resolution (9). The direct link between inflammatory commitment and resolution mediated by eicosanoid signaling in macrophages remains unclear from short-term vs. long-term priming, but the complete temporal changes and important interconnections within the entire eicosadome are now demonstrated.

Results

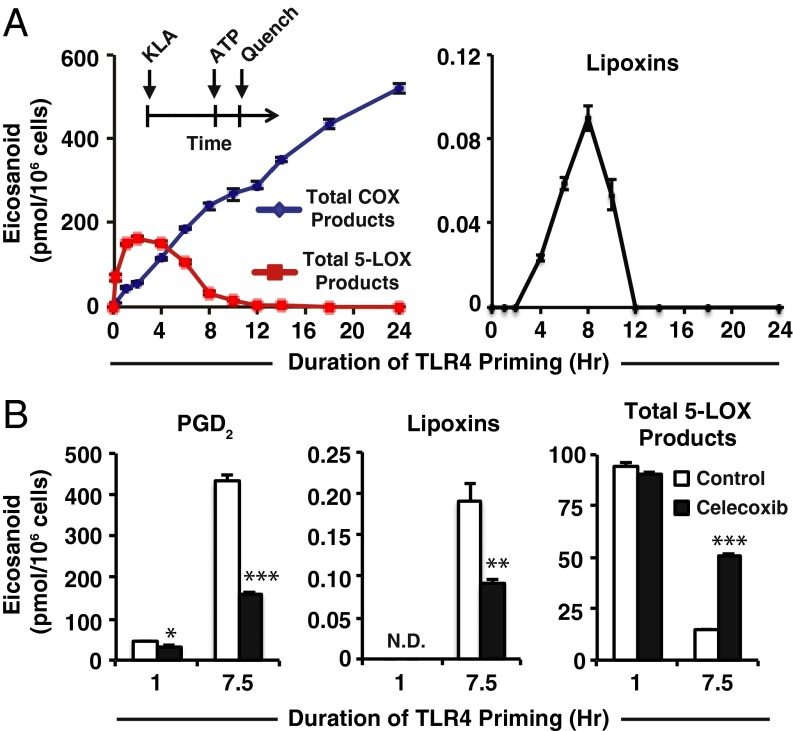

We first primed immortalized macrophage-like cells (RAW264.7) with the TLR4 agonist Kdo2 lipid A (KLA) for various times and examined the effects on subsequent purinergic stimulated COX and 5-LOX activity using targeted lipidomic monitoring (Fig. 1A). Total 5-LOX products (5-HETE, LTC4, 11-trans LTC4, LTB4, 6-trans,12-epi LTB4, 6-trans LTB4, and 12-epi LTB4) peaked at 2 h and diminished steadily at later time points; total levels from 12 to 24 h were less than 1% of maximal 2-h levels. Total COX products [PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGJ2, 15-deoxy PGD2, 15-deoxy PGJ2, 11-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (11-HETE) and 15-HETE] were lowest during short-term TLR4 priming and steadily increased with longer priming durations. AA levels in media were maximal with 2-h priming and were vastly reduced with 8-h priming and beyond (Fig. S1); AA release during major COX activity from 2 to 12 h may therefore be slower and/or coupled to COX-2.

Fig. 1.

Duration of TLR4 priming controls purinergic 5-LOX product formation and lipoxin biosynthesis. (A, Inset) Protocol for TLR4 priming (Kdo2 lipid A, KLA) starting at time = 0 followed by ATP stimulation at indicated times and subsequent reaction quench as endpoint (further details can be found in SI Materials and Methods); eicosanoid levels from RAW264.7 (RAW) cell medium after TLR4 priming with 100 ng/mL KLA for varying durations before stimulation with 2 mM ATP for the final 10 min include total COX products (PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGJ2, 15-deoxy PGD2, 15-deoxy PGJ2, 11-HETE, and 15-HETE); total 5-LOX products (5-HETE, LTC4, 11-trans LTC4, LTB4, 6-trans,12-epi LTB4, 6-trans LTB4, and 12-epi LTB4); lipoxins (LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4). (B) Levels of PGD2, lipoxins (LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4), and total 5-LOX products (as in A) from RAW medium after KLA priming for the indicated times in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of 50 nM celecoxib (∼IC50) followed by stimulation with ATP for the final 30 min; PGD2 levels were decreased with celecoxib treatment vs. control with 1-h TLR4 priming (*P < 0.01) and 7.5 h TLR4 priming (***P < 0.0001); lipoxin levels were not detected (N.D.) with 1 h priming and were decreased at 7.5 h TLR4 priming with celecoxib treatment vs. control (**P < 0.005); total 5-LOX products with 1-h priming were not significantly different with celecoxib vs. control, and at 7.5-h priming were increased with celecoxib vs. control (***P < 0.0001). Data are mean values of three separate experiments ± SEM.

The proresolution mediators lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and 15-epi–LXA4 were also detected between 4 and 10 h of TLR4 priming and peaked at 8 h (Fig. 1A). LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4 are trihydroxylated eicosanoids derived from 15(S)-HETE and 15(R)-HETE, respectively. The 15-HETE comprises ∼1–3% COX-2 metabolism in four different macrophage phenotypes, including RAW cells, after 8 h TLR4 stimulation (10). Here, lipoxins were formed between 4 and 10 h of TLR4 priming, after the initial phase when COX-2 and 5-LOX products were significantly elevated.

Celecoxib, which specifically inhibits COX-2 formation of PGH2, 11-HETE, and 15-HETE, caused a ∼50% decrease in formation of both PGD2 and lipoxins (Fig. 1B) at 50 nM [near the reported human COX-2 IC50 of 40 nM (11) and far below the COX-1 IC50 of 15 μM (11)], thus demonstrating that lipoxin biosynthesis in this system requires COX-2. Additionally, we observed a threefold increase in 5-LOX products vs. without celecoxib after 7.5 h of TLR4 priming (Fig. 1B), confirming that 5-LOX was still active and competes with COX-2 for AA. In the presence of both 1 μM PGE2 and 50 nM celecoxib, we observed no inhibition of total 5-LOX metabolism after long-term priming compared with treatment with celecoxib alone (Fig. S2), which rules out down-regulation of FLAP and reduced 5-LOX activity via PGE2-mediated IL-10 signaling that has been observed in dendritic cells (8). These results were then recapitulated in primary macrophages. Resident peritoneal macrophages (RPMs) express approximately twofold higher constitutive levels of 5-LOX and FLAP vs. RAW cells (Fig. S3) and twofold lower levels of COX-2 after TLR4 stimulation (10). RPMs produced lipoxins with long-term priming (Fig. S4 A and B), and increasing cell density increased the level (and concentration) of PGE2, but this did not limit lipoxin formation or 5-LOX metabolism of AA based on levels of LTC4 (Fig. S4 C and D). Thus, RPM and RAW macrophages both retain 5-LOX activity in the presence of exogenous or endogenous PGE2, unlike in dendritic cells (8). Ultimately, lipoxins from macrophages likely represent an additional source of the total that might be found in certain physiological environments. Lipoxins can be formed by coordinate conversion of endothelial COX-2/mucosal epithelial 15-LOX–derived 15-HETE with neutrophil 5-LOX, or neutrophil 5-LOX–derived LTA4 with platelet 12-LOX, which inhibit neutrophil extravasation (12). Macrophages initially recruit neutrophils via leukotriene and chemokine signaling in response to TLR signaling and may subsequently switch to forming lipoxins to inhibit neutrophil recruitment in response to high ATP levels.

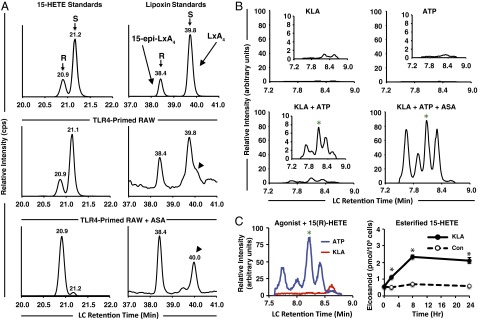

To assess the enzymatic control of lipoxin formation, chiral chromatography was used to determine the proportions of 15(R)-HETE and 15(S)-HETE in TLR4 primed/purinergic-stimulated RAW cells in the presence and absence of aspirin (ASA). Acetylation of COX-2 by ASA inhibits PG formation and enhances 15(R)-HETE formation (13). Non–ASA-treated cells produced 15(R)- and 15(S)-HETE at a ratio between 1:3 and 1:4 (R:S) (Fig. 2A), and produced both lipoxin epimers at a ratio of ∼1:2 (15-epi–LXA4:LXA4). In the presence of ASA, RAW cells produced almost exclusively 15(R)-HETE and 15-epi–LXA4. These results demonstrate that COX-2 activity with or without aspirin treatment can lead to formation of 15-epi–LXA4, which is more slowly inactivated by 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (PGDH) than LXA4 (12). Lipoxins are well known to be formed by either 12- or 15-LOX activity along with 5-LOX, although the additional contribution by COX-2 may partially explain the observance of delayed resolution caused by COX-2 inhibition or knockout in vivo (14, 15).

Fig. 2.

Chirality of lipoxins, requirement for priming, and separate effects of TLR4 and P2X7 stimulation. (A) MS monitoring was set to multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) transition 319(−) to 219(−) m/z for 15-HETE in the first period (Left column) and 351(−) to 115(−) m/z for lipoxins in the second period (Right column); intensity is expressed in counts per second, cps). Chiral separation of (Top row) 15(R)-HETE:15(S)-HETE standards at a 1:3 concentration and 15-epi–LXA4:LXA4 standards at a 1:3 concentration; (Middle row) RAW cell medium after 7.5 h KLA and final 30 min ATP; (Bottom row) RAW cell medium after 7.5 h KLA in the presence of 1 mM ASA and final 30 min ATP. Arrowheads indicate a species ∼12 s to the Right of LXA4. A total of ∼25 million cells in a T-75 tissue culture flask containing 5 mL medium was used for both conditions [this cell quantity is considerably higher than in other experiments due to decreased signal yielded in atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) mode]; n = 1. (B) RAW medium after (Upper Left) only KLA stimulation for 8 h; (Upper Right) no stimulation for 7.5 h before ATP for final 30 min; (Lower Left) 7.5 h KLA priming before ATP stimulation for final 30 min; (Lower Right) 7.5 h KLA priming in the presence of 1 mM ASA before ATP stimulation for final 30 min. Chromatogram traces represent 70-s scheduled monitoring of MRM transition 351(−) m/z to 115(−) m/z during nonchiral reverse-phase chromatographic separation on a scale of 100 arbitrary units (Insets are on a one order of magnitude lower scale); data represent one replicate of n = 3. (C, Left) Chromatograms (as in B) of RAW medium after 30 min KLA or ATP stimulation in the presence of 1 μM 15(R)-HETE; coelution with LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4 commercial standards are indicated with a green asterisk; (Right) 15-HETE levels from saponified phospholipids of RAW cells after KLA stimulation for the indicated times over a 24-h period represent mean values of three separate experiments ± SEM; 15-HETE levels were increased with KLA stimulation vs. control (*P < 0.001).

We then assessed the individual contributions of TLR4 and purinergic stimulation to macrophage lipoxin synthesis. LC-MS/MS chromatograms from incubations with only KLA for 7.5 h or ATP for 30 min contained no detectable peaks coeluting with lipoxins (Fig. 2B). Four peaks resulted from TLR4 primed, purinergic-stimulated RAW cells, with the third peak coeluting with LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4. TLR4 primed, purinergic-stimulated cells in the presence of ASA produced exponentially higher levels of four peaks observed in non–ASA-treated cells, and the third peak coeluted with LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4. ASA treatment partially inhibited COX prostanoids (Fig. S5A) and proportionally increased the levels of 15-HETE and lipoxins (Fig. S5 B and C). ASA has previously been shown to specifically increase COX-2–mediated formation of 15(R)-HETE and induce formation of aspirin-triggered lipoxins, including bioactive 15-epi–LXA4 in cocultures of endothelial cells and neutrophils (16). This same study also identified a cluster of peaks resembling those shown in Fig. 2B, which corresponded to 15-epi–LXA4, 15-epi–11-trans–LXA4, and other isomers with different double-bond geometry and C5 and C6 chirality deriving from a 15-epi–5,6-epoxytetraene intermediate (16). Importantly, low dose (75–81 mg/d) aspirin in humans has since been shown to be anti-inflammatory (17) and cardioprotective (18) via increases in 15-epi–LXA4. Our results determined that macrophages require both TLR4 priming and purinergic stimulation to synthesize lipoxins, and ASA exponentially enhances their formation. Consistent with this conclusion, RAW cells produced lipoxins in the presence of exogenous 1 μM 15(R)-HETE and ATP, but not KLA, after 30 min (Fig. 2C). Also, long-term stimulation with KLA (without adding 15-HETE) led to accumulation of 15-HETE in membrane phospholipids (Fig. 2C), and the levels in the extracellular medium increased after additional stimulation with ATP (Fig. S5B).

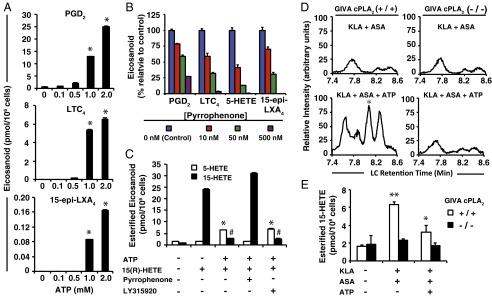

We then examined specific purinergic receptor requirements for lipoxin synthesis because most P2X and P2Y receptors can be activated by nanomolar ATP concentrations, whereas only P2X7 requires high micromolar–millimolar concentrations (19). In murine macrophages, P2X7 was previously shown to be responsible for the majority of eicosanoids generated with mM ATP (20). Lipoxin synthesis was confirmed to be dependent on P2X7 stimulation by varying the concentration of ATP in the presence of 1 μM 15(R)-HETE. PG and LT (Fig. 3A) and AA levels (Fig. S6) increased significantly only with mM ATP vs. midhigh μM ATP; 15-epi–LXA4 was only detected with mM ATP (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Millimolar ATP and cPLA2 are required for lipoxin biosynthesis in the presence of exogenous 15-HETE or TLR4 priming. (A) Extracellular eicosanoid levels from RAW cells after 30 min in the presence of 1 μM 15(R)-HETE along with the indicated concentrations of ATP (PGD2, LTC4, and lipoxin levels were higher with millimolar ATP levels vs. 0–500 μM ATP levels; *P < 0.001). (B) Extracellular eicosanoid levels from RAW cells preincubated for 30 min in the absence (control) or presence of the indicated concentrations of pyrrophenone; cells were then stimulated with ATP in the presence of 1 μM 15(R)-HETE for 30 min. (C) Eicosanoid levels in membrane phospholipids of RAW cells incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of ATP and/or 1 μM 15(R)-HETE, and absence or presence of 500 nM pyrrophenone or 5 μM LY315920 (varespladib); 5-HETE levels increased with 15(R)-HETE + ATP-treated cells in the absence/presence of LY315920 vs. untreated cells (*P < 0.0001), but not with pyrrophenone treatment or 15(R)-HETE treatment alone; 15-HETE levels decreased in cells treated with 15(R)-HETE + ATP in the presence/absence of LY315920 vs. treatment with pyrrophenone or with 15(R)-HETE treatment alone (#P < 0.0001). (D) Bone-marrow–derived macrophages generated from GIVA cPLA2 transgenic mice (Left column) (+/+) and (Right column) (−/−) were stimulated (Upper row) with 100 ng/mL KLA in the presence of 1 mM ASA for 8 h; (Lower row) with 100 ng/mL KLA in the presence of 1 mM ASA for 7.5 h before stimulation with 2 mM ATP for the final 30 min. Data are chromatograms of extracellular media generated as described in Fig. 2B and are representative of three separate experiments. Green asterisk indicates coelution with LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4 standards. (E) Levels of 15-HETE from membrane phospholipids in BMDM cells (from the same experiment as in D); 15-HETE levels in KLA + ASA vs. untreated cells (+/+) were increased (**P < 0.001); KLA + ASA + ATP vs. KLA + ASA-treated cells (+/+) were decreased (*P < 0.01); the same comparisons in (−/−) cells found no significant increases or decreases. Data are mean values of three separate experiments ± SEM.

Whereas formation of PG and 15-HETE by COX, and LT and 5-HETE by 5-LOX all require hydrolysis of esterified AA by cPLA2, it has generally been assumed that lipoxin production from 15-HETE is independent of cPLA2 action. However, we found that in the presence of 1 μM 15(R)-HETE and a potent, selective inhibitor of cPLA2 [without effect on FLAP or 5-LOX (21)], pyrrophenone, ATP-stimulated COX and 5-LOX arachidonate-derived product formation was dose dependently inhibited as expected, and yet 15-epi–LXA4 was also dose dependently inhibited (Fig. 3B).

It is known that 15-HETE supplied to neutrophils is rapidly esterified into membrane phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and other phospholipids and neutral lipids within 15 s to 20 min (22). Subsequent activation with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 is able to induce formation of LXA4 (22); however, the enzymes involved in 15-HETE liberation or hydrolysis from phospholipid precursors have not been elucidated. We found that RAW cells also rapidly incorporate exogenous 15-HETE into phospholipids, and levels decreased 10-fold in the presence of ATP with a concomitant increase in esterified 5-HETE levels (Fig. 3C). ATP-stimulated hydrolysis of esterified 15-HETE was completely abolished with pyrrophenone, but was unaffected by the group (G)IIA, V, and X sPLA2 inhibitor, LY315920 (varespladib). We additionally confirmed that a third macrophage phenotype, primary bone-marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), also produced lipoxins with TLR4 priming and 2 mM ATP (Fig. 3D). Genetic deletion of GIVA cPLA2 abolished lipoxin production (Fig. 3D), 15-HETE incorporation into phospholipids after TLR4 priming, and subsequent release of 15-HETE after ATP stimulation (Fig. 3E).

Discussion

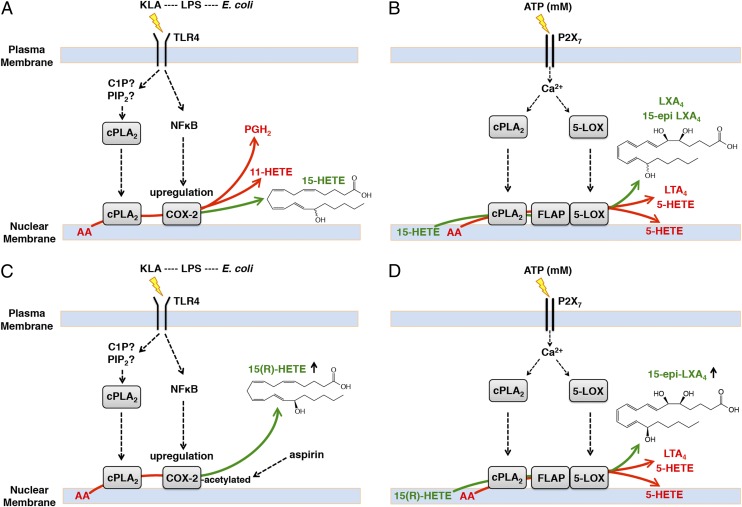

We have demonstrated here that 15-HETE generated by native and aspirin-acetylated COX-2 participates in classic membrane remodeling through which it is efficiently coupled to the cPLA2–FLAP–5-LOX pathway in parallel to AA during key inflammatory receptor stimulations (Fig. 4). Part of this mechanism elucidates the endogenous enzymatic efficiency by which lipoxin synthesis occurs in the established two-cell systems via transcellular metabolism, as well as in single-cell systems. Because FLAP and Ca2+-activated 5-LOX are primarily localized at the perinuclear membrane (23), release of AA by cPLA2 at this site is crucial for leukotriene synthesis, and 15-HETE conversion to lipoxins through FLAP and 5-LOX is under spatial and temporal constraints. The potential for cellular cPLA2 to hydrolyze 15-HETE was previously negated based on in vitro studies where activity was only observed when 15-HETE comprised 5 mol% or less in phospholipid vesicles (24). This observation is actually supportive, because 15-HETE levels measured in phospholipids after KLA stimulation (Fig. 2C) or with exogenous 15-HETE (Fig. 3C) were over 100-fold lower than AA levels we have previously measured (25), not counting the high levels of other fatty acids present in cells. Most interestingly, macrophages more efficiently convert esterified 15-HETE to lipoxins via priming vs. exogenous/transcellular routes (Fig. S7 A and B), which we propose is due to colocalization of COX-2, FLAP, and 5-LOX at the perinuclear membrane along with cPLA2. A phospholipase that is largely expressed in dendritic cells, group IID sPLA2, has also recently been found to contribute to proresolution mediator synthesis as well as the resolution of skin inflammation (26). Thus, coordination between different PLA2 isoforms may also be required to facilitate maximal proresolution mediator synthesis in physiological contexts.

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of inflammatory receptor-mediated formation of lipoxins in macrophages. (A) Macrophages expressing TLR4 (and likely other TLRs) recognize pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) species [such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from Escherechia coli, which contains the TLR4 ligand Kdo2-lipid A (KLA)] leading to activation of PLA2 hydrolysis of esterified AA and increased expression of COX-2. The majority of AA oxygenated by up-regulated COX-2 forms PGH2 (∼90–93%; via the cyclooxygenase and peroxidase active sites) and ∼4–6% is converted to 11-HETE (via the cyclooxygenase active site), and a smaller portion (∼1–3%) is converted to 15-HETE (∼30% R, ∼70% S; via the peroxidase active site). The 15-HETE is secreted from the cell, but a portion is esterified within membrane phospholipids through several possible routes putatively via fatty acyl CoA ligase. (B) Concomitantly, extracellular millimolar ATP generated by necrotized cells, PAMP recognizing cells, and recruited/activated neutrophils (reviewed in ref. 1) during a pathogenic/inflammatory assault stimulates the P2X7 receptor in macrophages. This leads to an increase in macrophage intracellular Ca2+, activating cPLA2 and 5-LOX via translocation primarily to the perinuclear membrane. LTA4 and derived metabolites, along with 5-HETE, are produced by cPLA2-mediated AA hydrolysis, assistance of FLAP, and 5-LOX metabolism. Some 5-HETE becomes esterified in cell membranes (depicted in perinuclear phospholipids but potentially in other organelles as well); the rest diffuses from the cell. Esterified 15-HETE is also hydrolyzed by cPLA2, and a portion is then converted to LXA4 and 15-epi–LXA4; hydrolysis of 15-HETE is required to enhance metabolism by 5-LOX via coupling with cPLA2 and FLAP. (C) In the presence of aspirin, acetylated COX-2 produces ∼100% 15(R)-HETE (and at significantly higher levels than with native enzyme). (D) Esterified 15(R)-HETE is subsequently released and converted to 15-epi–LXA4 at enhanced levels after P2X7 stimulation.

Increased PGE2 derived from up-regulated COX-2 during inflammation is the primary target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to treat arthritis and many other inflammatory conditions because of the strong association between PGE2 receptor EP signaling and pain, yet EP signaling also attenuates TNF-α expression and up-regulates IL-10 in macrophages (27) and can increase lipoxin production in vivo during inflammation (15). Omega-3 fatty acids and aspirin more strongly inhibit COX-1 vs. COX-2 to promote cardioprotective actions and also partly avoid the aforementioned proinflammatory effects of COX-2 inhibitors. Still, the results presented herein suggest that therapeutic strategies should also be directed to the membrane where eicosanoids can be conditionally introduced into membrane remodeling cycles that have important implications in inflammation. Although eicosanoids have been exhaustively studied as secreted mediators, we anticipate that the complete elucidation of the fates and functions of eicosanoids in membranes will uncover new strategies for controlling pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling.

Materials and Methods

Methods used for cell stimulation and quantitation (6), eicosanoid analysis (28, 29), transcript quantitation, primary macrophage isolation/ex vivo culture (10), and phospholipid extraction/saponification (25) were all described in previous papers, which also established appropriate sample sizes used in this study. RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (cat. no. TIB-71). Full protocols are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Animals.

Male, 10-wk-old, C57bl/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice exhibiting skin lesions or visible tumors were excluded from the study. All experiments were carried out according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of California, San Diego.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Student t test; P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Joseph V. Bonventre and Dr. Eileen O’Leary for graciously providing bones from GIVA cPLA2 (+/+) and (−/−) mice, and Dr. Oswald Quehenberger and Dr. Alexander Andreyev for assistance with manuscript preparation. This work was supported by the Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy Large Scale Collaborative Grant U54 GM069338 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and P.C.N. received support from the University of California, San Diego Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology (NIH Grant T32 GM007752).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1404372111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ferrari D, et al. The P2X7 receptor: A key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):3877–3883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari D, et al. Extracellular ATP triggers IL-1 beta release by activating the purinergic P2Z receptor of human macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159(3):1451–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solle M, et al. Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(1):125–132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahlenberg JM, Lundberg KC, Kertesy SB, Qu Y, Dubyak GR. Potentiation of caspase-1 activation by the P2X7 receptor is dependent on TLR signals and requires NF-kappaB-driven protein synthesis. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7611–7622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki K, et al. Lipopolysaccharide primes human alveolar macrophages for enhanced release of superoxide anion and leukotriene B4: Self-limitations of the priming response with protein synthesis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8(5):500–508. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buczynski MW, et al. TLR-4 and sustained calcium agonists synergistically produce eicosanoids independent of protein synthesis in RAW264.7 cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(31):22834–22847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey MJ, Phare SM, Peters-Golden M. Prolonged exposure to lipopolysaccharide inhibits macrophage 5-lipoxygenase metabolism via induction of nitric oxide synthesis. J Immunol. 2000;165(7):3592–3598. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harizi H, Juzan M, Moreau JF, Gualde N. Prostaglandins inhibit 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein expression and leukotriene B4 production from dendritic cells via an IL-10-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170(1):139–146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: Signals in resolution. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(7):612–619. doi: 10.1038/89759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris PC, Reichart D, Dumlao DS, Glass CK, Dennis EA. Specificity of eicosanoid production depends on the TLR-4-stimulated macrophage phenotype. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90(3):563–574. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penning TD, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of the 1,5-diarylpyrazole class of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: Identification of 4-[5-(4-methylphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl]benze nesulfonamide (SC-58635, celecoxib) J Med Chem. 1997;40(9):1347–1365. doi: 10.1021/jm960803q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory circuitry: Lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor ALX. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73(3-4):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecomte M, Laneuville O, Ji C, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. Acetylation of human prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) by aspirin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(18):13207–13215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaho VA, Mitchell WJ, Brown CR. Arthritis develops but fails to resolve during inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 in a murine model of Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1485–1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan MM, Moore AR. Resolution of inflammation in murine autoimmune arthritis is disrupted by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition and restored by prostaglandin E2-mediated lipoxin A4 production. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6418–6426. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clària J, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers previously undescribed bioactive eicosanoids by human endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(21):9475–9479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris T, et al. Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans. J Immunol. 2009;183(3):2089–2096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang N, Bermudez EA, Ridker PM, Hurwitz S, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers antiinflammatory 15-epi-lipoxin A4 and inhibits thromboxane in a randomized human trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(42):15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405445101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Virgilio F, et al. Nucleotide receptors: An emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97(3):587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balboa MA, Balsinde J, Johnson CA, Dennis EA. Regulation of arachidonic acid mobilization in lipopolysaccharide-activated P388D(1) macrophages by adenosine triphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36764–36768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flamand N, et al. Effects of pyrrophenone, an inhibitor of group IVA phospholipase A2, on eicosanoid and PAF biosynthesis in human neutrophils. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(4):385–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brezinski ME, Serhan CN. Selective incorporation of (15S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in phosphatidylinositol of human neutrophils: Agonist-induced deacylation and transformation of stored hydroxyeicosanoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(16):6248–6252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newcomer ME, Gilbert NC. Location, location, location: Compartmentalization of early events in leukotriene biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(33):25109–25114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.125880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nigam S, Schewe T. Phospholipase A(2)s and lipid peroxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488(1-2):167–181. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norris PC, Dennis EA. Omega-3 fatty acids cause dramatic changes in TLR4 and purinergic eicosanoid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(22):8517–8522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200189109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miki Y, et al. Lymphoid tissue phospholipase A2 group IID resolves contact hypersensitivity by driving antiinflammatory lipid mediators. J Exp Med. 2013;210(6):1217–1234. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinomiya S, et al. Regulation of TNFalpha and interleukin-10 production by prostaglandins I(2) and E(2): Studies with prostaglandin receptor-deficient mice and prostaglandin E-receptor subtype-selective synthetic agonists. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61(9):1153–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumlao DS, Buczynski MW, Norris PC, Harkewicz R, Dennis EA. High-throughput lipidomic analysis of fatty acid derived eicosanoids and N-acylethanolamines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811(11):724–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkewicz R, Fahy E, Andreyev A, Dennis EA. Arachidonate-derived dihomoprostaglandin production observed in endotoxin-stimulated macrophage-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(5):2899–2910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.