Abstract

The slow acquisition of protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria probably reflects the extensive diversity of important antigens. The variant surface antigens (VSA) that mediate parasite adhesion to a range of host molecules are regarded as important targets of acquired protective immunity, but their diversity makes them questionable vaccine candidates. We determined levels of VSA-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) in human plasma collected at four geographically distant and epidemiologically distinct localities with specificity for VSA expressed by P. falciparum isolates from three African countries. Plasma levels of VSA-specific IgG recognizing individual parasite isolates depended on the transmission intensity at the site of plasma collection but were largely independent of the geographical origin of the parasites. The total repertoire of immunologically distinct VSA thus appears to be finite and geographically conserved, most likely due to functional constraints. Furthermore, plasma samples frequently had high IgG reactivity to VSA expressed by parasites isolated more than 10 years later, showing that the repertoire is also temporally stable. Parasites from patients with severe malaria expressed VSA (VSASM) that were better recognized by plasma IgG than VSA expressed by other parasites, but importantly, VSASM-type antigens also appeared to show substantial antigenic homogeneity. Our finding that the repertoire of immunologically distinct VSA in general, and in particular that of VSASM, is geographically and temporally conserved raises hopes for the feasibility of developing VSA-based vaccines specifically designed to accelerate naturally acquired immunity, thereby enhancing protection against severe and life-threatening P. falciparum malaria.

Plasmodium falciparum expresses clonally variant surface antigens (VSA) on the membrane of infected erythrocytes (IE), including the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) molecules mediating IE adhesion to host vascular endothelium (reviewed in reference 21). Naturally acquired protective immunity against P. falciparum malaria appears to depend to a considerable extent on the acquisition of a broad repertoire of VSA-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) (24, 25), implying that VSA are under strong immune selection. Indeed, the var genes encoding PfEMP1 display high inter- and intraclonal diversity (12, 19, 22, 39) generated by frequent recombination events (37), and this may prevent the development of useful VSA-based vaccines. On the other hand, the role of VSA as receptor-specific adhesins can be expected to impose functional constraints on variation, and subfamilies of var genes with very high conservation of structure and even sequence, presumably dictated at least in part by functional requirements, have been identified (13, 23, 31-34, 40).

Several studies have shown that parasites isolated from patients with severe and complicated P. falciparum malaria express VSA (VSASM) that are serologically distinct from those expressed by parasites involved in uncomplicated disease and asymptomatic infections (VSAUM) (6, 7, 28). Thus, while most malaria-exposed individuals in a given area have significant, and often high, levels of IgG with specificity for VSASM-expressing IE from the same area, VSAUM-specific antibodies are less prevalent and the levels are generally much lower. Several hypotheses can accommodate this observation. However, the fact that VSASM-type parasites predominate among young and nonimmune patients whereas VSAUM-type parasites prevail in older, partially immune individuals (6, 28) suggests that VSASM-specific immunity is developed earlier than VSAUM-specific immunity, probably because VSASM are less antigenically diverse than VSA in general and VSAUM in particular, at least locally. However, to our knowledge, only a single study has investigated the degree of VSA conservation across large distances (2), and this was thus the aim of the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and plasma samples.

We used plasma samples obtained from healthy individuals living in four geographically distant and epidemiologically distinct study sites to type parasite VSA expression. Transmission intensity at the sites was evaluated by a combination of data on spleen rates, parasite rates, and entomological inoculation rates (1, 2, 4, 11, 18, 38). Intensities ranged from very intense, year-round transmission in Indonesia through intense but seasonal transmission in coastal Ghana and moderate intensity in the highlands of northeastern Tanzania to low and unstable transmission in eastern Sudan. The samples were collected in 1985 in Indonesia from 40 adult residents of Hiripao, Mapurujaya, and Moare villages, Irian Jaya; in 1994 from 96 Ghanaian children, aged 3 to 8 years, living in the town of Dodowa; at the end of the 1995 malaria season from 57 residents, aged 7 to 31, years living in Daraweesh village, Sudan; and in 2001 from 45 children, aged 4 to 12 years, living in Ubiri village, Tanzania. Samples from six Danish adults without history of travel to malarious areas were used as negative controls. The relevant ethical review boards had approved all studies, and all study subjects or parents had given informed signed consent to participate.

Parasite isolates and in vitro cultivation.

We used 88 P. falciparum patient isolates in the study. Of these isolates, 68 were obtained from children aged 3 to 11 years and admitted in 1998 to the Department of Child Health, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana (28). An additional eight parasite isolates were isolated from malarious residents of Daraweesh, Sudan, as part of long-term epidemiological surveillance (15). Finally, 12 isolates were obtained from children aged 3 to 10 years with asymptomatic P. falciparum parasitemia living in Mgome village of northeastern Tanzania (26). From each patient, IE were collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen as previously described (15). Cryopreserved IE were subsequently thawed and adapted to in vitro culture as previously described (14).

Typing of VSA expression by flow cytometry.

We used flow cytometry (FCM) to type the VSA expressed by each isolate (28, 35). In brief, parasite cultures were enriched to contain >75% erythrocytes infected by late-trophozoite- and schizont-stage parasites by exposure to a strong magnetic field (30, 35). Enriched aliquots (2 × 105 IE) were labeled for parasite DNA by ethidium bromide (to allow the exclusion of remaining uninfected red blood cells from FCM data analysis) and sequentially exposed to plasma (5 μl), secondary goat-anti-human IgG (0.4 μl; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), and tertiary fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit-anti-goat Ig (4 μl; Dako). FCM data from a minimum of 5,000 IE were acquired by using a FACScan instrument (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). For each sample, the mean fluorescence index (MFI) was recorded as a measure of VSA-specific IgG reactivity (35). Nonspecific labeling was evaluated by analysis of uninfected (ethidium bromide-negative) erythrocytes. All samples relating to a particular parasite isolate were processed and analyzed in a single assay. However, due to limitations in amounts of plasma available, not all parasite isolates were tested with all plasma samples (Table 1). To be able to compare VSA IgG levels between isolates and plasma samples, we subtracted the mean plus two standard deviations of log MFI values obtained with the six control samples from all test MFI values.

TABLE 1.

Number of parasite-plasma combinations used for characterization of variant surface antigen expression

| Source of plasma samples | No. of isolates fromb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana (n = 68) | Tanzania (n = 12) | Sudan (n = 8) | |

| Irian Jaya (n = 40) | ND | ND | 320 |

| Ghana (n = 96) | 6,528 | 1,152 | 768 |

| Tanzania (n = 45) | ND | 540 | 360 |

| Sudan (n = 57) | 3,705a | 684 | 456 |

Three of the Ghanaian parasite isolates were not typed with Sudanese plasma samples.

ND, not determined.

Statistical analysis.

Levels of VSA-specific IgG levels in plasma samples from different geographical areas were compared by Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks as appropriate. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Average VSA-specific IgG reactivity reflects transmission intensity.

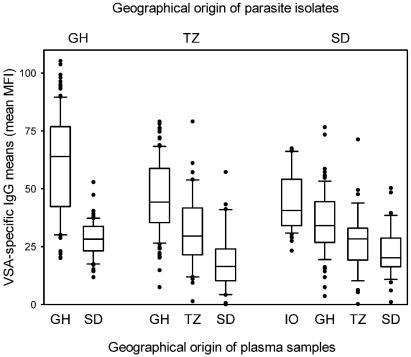

We first compared plasma levels of IgG with specificity for VSA expressed by sympatric and allopatric parasite isolates. Levels of IgG with specificity for VSA expressed by the Ghanaian, Tanzanian, and Sudanese isolates all depended significantly (P < 0.001 in all cases) on the transmission intensity in the area of the plasma samples (Indonesia > Ghana > Tanzania > Sudan) (Fig. 1). The proportion of samples from the different locations with significant VSA-specific antibody levels (i.e., greater than the mean plus two standard deviations of negative control samples) followed the same pattern (82, 80, 45, and 18%, respectively). In contrast, we did not find systematically higher IgG reactivity with specificity for sympatric parasite isolates, suggesting that the repertoires of immunodominant, antigenically distinct VSA are alike at geographically distant locations, in line with previous data from Aguiar et al. (2). Taken together, these findings show that endemicity at the site of plasma collection is the main determinant of average levels of VSA-specific IgG, whereas the geographical origin of the parasites expressing the VSA under study is of minor importance.

FIG. 1.

VSA-specific plasma IgG levels in relation to the geographical origins of the plasma sample and of the VSA-expressing parasite isolate. Each data point (Table 1) represents the mean of MFI values obtained with an individual plasma sample (IO, Indonesia; GH, Ghana; TZ, Tanzania; SD, Sudan) tested against P. falciparum isolates from Ghana (left), Tanzania (center), and Sudan (right). Centerlines indicate medians, boxes indicate the central 50% of data points, and bars indicate the central 80% of data points.

VSA that are locally well recognized by plasma IgG are globally well recognized and vice versa.

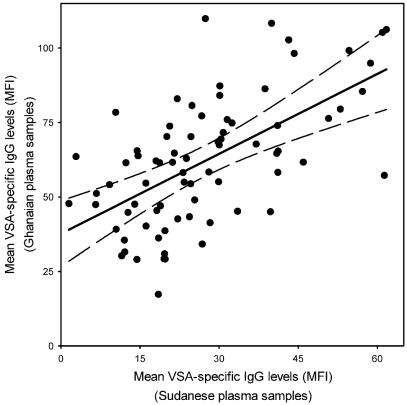

Previous studies have shown that IgG reactivity to VSA expressed by parasites from a given locality vary widely (7, 28). Thus, parasites isolated from young patients and patients with severe malaria tend to express VSASM that are commonly recognized by IgG in plasma samples from the same area. In contrast, parasites isolated from older patients and patients with uncomplicated malaria or asymptomatic infection tend to express VSAUM that are rarely and poorly recognized. To test if this pattern extends beyond geographically confined areas, we compared the geometric means of IgG with specificity for each of 76 Ghanaian, Tanzanian, and Sudanese parasite isolates in plasma samples from Ghana and Sudan. We found a highly significant linear correlation between isolate-specific levels of VSA-recognizing IgG in the Ghanaian and Sudanese plasma samples (r = 0.61) (Fig. 2). This finding shows that categorization of VSA into those of the VSASM type commonly and highly recognized by IgG and those of the VSAUM type poorly and rarely recognized did not critically depend on the marked differences in geographical location and endemicity of the plasma collection sites. This result constitutes an important extension of earlier observations on the relationship between VSA expression and disease severity (6, 28).

FIG. 2.

Geographical conservation of VSA. Data points represent the geometric mean of MFI values obtained for each of 76 individual P. falciparum isolates from Ghana, Tanzania, and Sudan tested against plasma samples from Ghana (n = 96) and Sudan (n = 57). The linear regression line and the 95% confidence interval for the regression line are indicated.

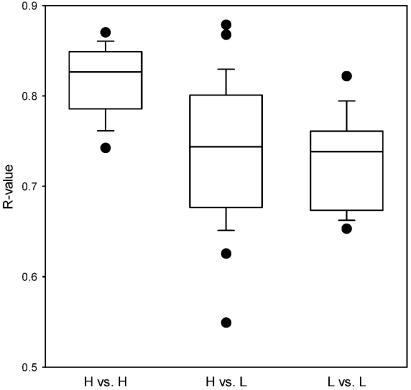

VSASM are antigenically more similar to each other than are VSAUM.

The data presented above, in conjunction with earlier findings, indicate the existence of a restricted subset of VSA that are associated with severe malaria and that this subset shows a recognizable degree of conservation of immunologically important epitopes worldwide. To compare the degree of conservation between individual VSASM-type molecules, we selected the five Ghanaian parasites that scored highest (H) (H1 to H5) in terms of average VSA-specific IgG levels in the set of 96 Ghanaian plasma samples (see reference 28 for details). These parasites were all isolated from Ghanaian patients with strictly defined severe and complicated malaria (20, 28). We next calculated the correlation coefficient of isolate-specific MFI values for each of the 10 pair-wise permutations of these isolates (r of H1 versus H2, H1 versus H3, H3 versus H5, etc.). In each case, we obtained highly significant r values that were close to 1 (Fig. 3), indicating a high degree of overlap between antigenic epitopes in the VSA expressed by these isolates. Interestingly, these r values were also significantly higher and more similar to each other than r values calculated in the same way for the five lowest-scoring isolates (L) of the VSAUM type isolated from Ghanaian patients with uncomplicated malaria (L1 to L5) (P = 0.0003) or r values obtained by the 25 pair-wise permutations of the H and L isolates (r of H1 versus L1, H2 versus L4, etc.) (P = 0.003) (Fig. 3). Analysis with Sudanese plasma samples for isolate typing yielded similar results (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that SM-type VSA constitute a subset that is antigenically distinct from UM-type VSA and that VSASM are more similar to each other than are other VSA.

FIG. 3.

Antigenic similarity of VSA in relation to serologically defined VSA type (VSASM [n = 5] or VSAUM [n = 5]; see the text for details). Each data point represents the correlation coefficient (R value) obtained from the comparison of a pair-wise permutation of the five most recognized (H1 to H5) and the five least recognized (L1 to L5) parasite isolates tested with a panel of 96 Ghanaian plasma samples (see the text for details). Permutations among well-recognized parasites only (H versus H), among poorly recognized parasites only (L versus L), and mixed permutations (pairs of one well-recognized and one poorly recognized isolate; H versus L) are shown separately. Centerlines indicate medians, boxes indicate the central 50% of data points, bars indicate the central 80% of data points, and circles indicate individual outliers.

DISCUSSION

Individuals living in areas with endemic transmission of P. falciparum parasites develop substantial protective immunity to malaria over a period of several years and after repeated disease episodes. Protective immunity developed this way is mediated mainly by IgG (10, 27). The mechanisms underlying the slow development of protective immunity are unclear, but the extensive inter- and intraclonal variation among parasite-encoded VSA on the IE surface seems to be of major importance (8, 24, 25, 28, 29).

A malaria episode involves parasites expressing VSA to which the patient has no preexisting variant-specific antibody response (8, 14, 29) but also leads to a marked IgG response with specificity for the VSA expressed by the parasites causing the malaria attack (14, 29). Recent studies have documented that VSA expressed by parasites infecting nonimmune patients, in whom they tend to cause severe and life-threatening disease, differ in terms of antibody recognition from VSA expressed by parasites infecting individuals with partially protective immunity, where the parasites tend to cause uncomplicated disease or asymptomatic infection (6, 7, 28). This finding indicates that VSA expression is regulated by acquired immunity and that immune-mediated selection against the VSASM-type parasites occurs earlier in life than it does against VSAUM-expressing parasites (6, 28). This deduction is supported by the fact that acquisition of immunity to severe disease precedes that to uncomplicated and asymptomatic infection (16). These findings raise the hope that it may be possible to develop vaccines based on VSASM-type antigens designed to protect against severe disease rather than against parasitemia per se. In pursuance of this goal, a method of in vitro selection for VSASM expression has recently been reported (36) and was used for the identification of PfEMP1-encoding genes that are upregulated following selection for VSASM expression (Jensen et al., submitted for publication). Obviously, the feasibility of this approach is highly dependent upon the level of conservation among different members of the VSASM subfamily. Parasite virulence has been linked to the expression of VSA allowing particularly efficacious sequestration of IE through simultaneous interaction with several host receptors (9, 17). This necessity for the expression of multiple adhesive domains must impose considerable constraints on the three-dimensional structure of the VSA involved, suggesting that such VSA may intrinsically be more similar to each other than VSA generally are, in line with the present findings. Although several studies have demonstrated extensive sequence diversity of VSA both between and within clones, our data suggest that such diversity does not necessarily translate into serological diversity, similar to what has been proposed with respect to the antigenic diversity of Trypanosoma brucei (3). In fact, a wealth of data are emerging supporting this scenario, at least insofar as the PfEMP1 family is concerned (13, 23, 31-34, 40). The results presented here, which were obtained by a serological rather than by a molecular biological approach, lend this scenario further support.

Apart from the above-mentioned main finding of the present study, our data also suggest that the slow acquisition of antimalarial immunity is not due to continuous generation of new variants, since we often found high levels of IgG with specificity for VSA expressed by parasites isolated more than a decade after the collection of the plasma sample. Finally, these data disfavor explanations proposing that the slow acquisition of immunity reflects the existence of local variants that are antigenically distinct from neighboring variants, in agreement with previous studies of this issue (5).

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Enhancement of Research Capacity in Developing Countries program of the Danish International Development Assistance (grants 104.Dan.8.L.306 and 104.Dan.8.L.401) and the Commission of the European Communities (grant QLK2-CT-1999-01293 [EUROMALVAC]).

Kirsten Pihl is thanked for excellent technical assistance.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afari, E. A., M. Appawu, S. Dunyo, A. Baffoe-Wilmot, and F. K. Nkrumah. 1995. Malaria infection, morbidity and transmission in two ecological zones in southern Ghana. Afr. J. Health Sci. 2:312-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguiar, J. C., G. R. Albrecht, P. Cegielski, B. M. Greenwood, J. B. Jensen, G. Lallinger, A. Martinez, I. A. McGregor, J. N. Minjas, J. Neequaye, M. E. Patarroyo, J. A. Sherwood, and R. J. Howard. 1992. Agglutination of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from East and West African isolates by human sera from distant geographic regions. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 47:621-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum, M. L., J. A. Down, A. M. Gurnett, M. Carrington, M. J. Turner, and D. C. Wiley. 1993. A structural motif in the variant surface glycoproteins of Trypanosoma brucei. Nature 362:603-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bødker, R., J. Akida, D. Shayo, W. Kisinza, H. A. Msangeni, E. M. Pedersen, and S. W. Lindsay. 2003. Relationship between altitude and intensity of malaria transmission in the Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. J. Med. Entomol. 40:706-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray, R. S., A. E. Gunders, R. W. Burgess, and J. B. Freeman. 1962. The inoculation of semi-immune Africans with sporozoites of Laverania falcipara (Plasmodium falciparum) in Liberia. Riv. Malariol. 41:199-210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull, P. C., M. Kortok, O. Kai, F. Ndungu, A. Ross, B. S. Lowe, C. I. Newbold, and K. Marsh. 2000. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes: agglutination by diverse Kenyan plasma is associated with severe disease and young host age. J. Infect. Dis. 182:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull, P. C., B. S. Lowe, M. Kortok, and K. Marsh. 1999. Antibody recognition of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte surface antigens in Kenya: evidence for rare and prevalent variants. Infect. Immun. 67:733-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bull, P. C., B. S. Lowe, M. Kortok, C. S. Molyneux, C. I. Newbold, and K. Marsh. 1998. Parasite antigens on the infected red cell are targets for naturally acquired immunity to malaria. Nat. Med. 4:358-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Q. J., A. Heddini, A. Barragan, V. Fernandez, S. F. A. Pearce, and M. Wahlgren. 2000. The semiconserved head structure of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 mediates binding to multiple independent host receptors. J. Exp. Med. 192:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen, S., I. A. McGregor, and S. Carrington. 1961. Gammaglobulin and acquired immunity to human malaria. Nature 192:733-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellman, R., C. Maxwell, R. Finch, and D. Shayo. 1998. Malaria and anaemia at different altitudes in the Muheza district of Tanzania: childhood morbidity in relation to level of exposure to infection. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 92:741-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler, E. V., J. M. Peters, M. L. Gatton, N. Chen, and Q. Cheng. 2002. Genetic diversity of the DBLα region in Plasmodium falciparum var genes among Asia-Pacific isolates. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 120:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried, M., and P. E. Duffy. 2002. Two DBLγ subtypes are commonly expressed by placental isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giha, H. A., T. Staalsoe, D. Dodoo, I. M. Elhassan, C. Roper, G. M. Satti, D. E. Arnot, T. G. Theander, and L. Hviid. 1999. Nine-year longitudinal study of antibodies to variant antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 67:4092-4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giha, H. A., T. Staalsoe, D. Dodoo, I. M. Elhassan, C. Roper, G. M. H. Satti, D. E. Arnot, L. Hviid, and T. G. Theander. 1999. Overlapping antigenic repertoires of variant antigens expressed on the surface of erythrocytes infected by Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 119:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta, S., R. W. Snow, C. A. Donnelly, K. Marsh, and C. Newbold. 1999. Immunity to non-cerebral severe malaria is acquired after one or two infections. Nat. Med. 5:340-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heddini, A., F. Pettersson, O. Kai, J. Shafi, J. Obiero, Q. Chen, A. Barragan, M. Wahlgren, and K. Marsh. 2001. Fresh isolates from children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria bind to multiple receptors. Infect. Immun. 69:5849-5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen, J. B., S. L. Hoffman, M. T. Boland, M. A. Akood, L. W. Laughlin, L. Kurniawan, and H. A. Marwoto. 1984. Comparison of immunity to malaria in Sudan and Indonesia: crisis-form versus merozoite-invasion inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:922-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchgatter, K., R. Mosbach, and H. A. Del Portillo. 2000. Plasmodium falciparum: DBL-1 var sequence analysis in field isolates from Central Brazil. Exp. Parasitol. 95:154-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtzhals, J. A., V. Adabayeri, B. Q. Goka, B. D. Akanmori, J. O. Oliver-Commey, F. K. Nkrumah, C. Behr, and L. Hviid. 1998. Low plasma concentrations of interleukin 10 in severe malarial anaemia compared with cerebral and uncomplicated malaria. Lancet 351:1768-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyes, S., P. Horrocks, and C. Newbold. 2001. Antigenic variation at the infected red cell surface in malaria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:673-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyes, S., H. Taylor, A. Craig, K. Marsh, and C. Newbold. 1997. Genomic representation of var gene sequences in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from different geographic regions. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 87:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavstsen, T., A. Salanti, A. T. R. Jensen, D. E. Arnot, and T. G. Theander. 2003. Sub-grouping of Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 var genes based on sequence analysis of coding and non-coding regions. Malar. J. 2:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh, K., and R. J. Howard. 1986. Antigens induced on erythrocytes by P. falciparum: expression of diverse and conserved determinants. Science 231:150-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsh, K., L. Otoo, R. J. Hayes, D. C. Carson, and B. M. Greenwood. 1989. Antibodies to blood stage antigens of Plasmodium falciparum in rural Gambians and their relation to protection against infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massaga, J. J., A. Y. Kitua, M. M. Lemnge, J. A. Akida, L. N. Malle, A. M. Ronn, T. G. Theander, and I. C. Bygbjerg. 2003. Effect of intermittent treatment with amodiaquine on anaemia and malarial fevers in infants in Tanzania: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 361:1853-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGregor, I. A., S. P. Carrington, and S. Cohen. 1963. Treatment of East African P. falciparum malaria with West African human γ-globulin. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57:170-175. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen, M. A., T. Staalsoe, J. A. L. Kurtzhals, B. Q. Goka, D. Dodoo, M. Alifrangis, T. G. Theander, B. D. Akanmori, and L. Hviid. 2002. Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigen expression varies between isolates causing severe and non-severe malaria and is modified by acquired immunity. J. Immunol. 168:3444-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ofori, M. F., D. Dodoo, T. Staalsoe, J. A. L. Kurtzhals, K. Koram, T. G. Theander, B. D. Akanmori, and L. Hviid. 2002. Malaria-induced acquisition of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigens. Infect. Immun. 70:2982-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul, F., S. Roath, D. Melville, D. C. Warhurst, and J. O. Osisanya. 1981. Separation of malaria-infected erythrocytes from whole blood: use of a selective high-gradient magnetic separation technique. Lancet ii:70-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson, B. A., T. L. Welch, and J. D. Smith. 2003. Widespread functional specialization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 family members to bind CD36 analysed across a parasite genome. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1265-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe, J. A., S. A. Kyes, S. J. Rogerson, H. A. Babiker, and A. Raza. 2002. Identification of a conserved Plasmodium falciparum var gene implicated in malaria in pregnancy. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1207-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salanti, A., A. T. R. Jensen, H. D. Zornig, T. Staalsoe, L. Joergensen, M. A. Nielsen, A. Khattab, D. E. Arnot, M. Q. Klinkert, L. Hviid, and T. G. Theander. 2002. A sub-family of common and highly conserved var genes expressed by CSA-adhering Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salanti, A., T. Staalsoe, T. Lavstsen, A. T. R. Jensen, M. P. K. Sowa, D. E. Arnot, L. Hviid, and T. G. Theander. 2003. Selective upregulation of a single distinctly structured var gene in CSA-adhering Plasmodium falciparum involved in pregnancy-associated malaria. Mol. Microbiol. 49:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staalsoe, T., H. A. Giha, D. Dodoo, T. G. Theander, and L. Hviid. 1999. Detection of antibodies to variant antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes by flow cytometry. Cytometry 35:329-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staalsoe, T., M. A. Nielsen, L. S. Vestergaard, A. T. R. Jensen, T. G. Theander, and L. Hviid. In vitro selection of Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 for expression of variant surface antigens associated with severe malaria in African children. Parasite Immunol. 25:421-427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Taylor, H. M., S. A. Kyes, and C. I. Newbold. 2000. Var gene diversity in Plasmodium falciparum is generated by frequent recombination events. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 110:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theander, T. G. 1998. Unstable malaria in Sudan: the influence of the dry season. Malaria in areas of unstable and seasonal transmission. Lessons from Daraweesh. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92:589-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward, C. P., G. T. Clottey, M. Dorris, D.-D. Ji, and D. E. Arnot. 1999. Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum PfEMP-1/var genes indicates that recombination rearranges constrained sequences. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 102:167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winter, G., Q. Chen, K. Flick, P. Kremsner, V. Fernandez, and M. Wahlgren. 2003. The 3D7var5.2 (varCOMMON) type var gene family is commonly expressed in non-placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 127:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]