Abstract

Objectives

Community-acquired pneumonia is associated with a significant long-term mortality after initial recovery. It has been acknowledged that additional research is urgently needed to examine the contributors to this long-term mortality. The objective of the present study was to assess whether diabetes or newly discovered hyperglycaemia during pneumonia affects long-term mortality.

Design

A prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting

A single secondary centre in eastern Finland.

Participants

153 consecutive hospitalised patients who survived at least 30 days after mild-to-moderate community-acquired pneumonia.

Interventions

Plasma glucose levels were recorded seven times during the first day on the ward. Several possible confounders were also recorded. The surveillance status and causes of death were recorded after median of 5 years and 11 months.

Results

In multivariate Cox regression analysis, a previous diagnosis of diabetes among the whole population (adjusted HR 2.84 (1.35–5.99)) and new postprandial hyperglycaemia among the non-diabetic population (adjusted HR 2.56 (1.04–6.32)) showed independent associations with late mortality. New fasting hyperglycaemia was not an independent predictor. The mortality rates at the end of follow-up were 54%, 37% and 10% among patients with diabetes, patients without diabetes with new postprandial hyperglycaemia and patients without diabetes without postprandial hyperglycaemia, respectively (p<0.001). The underlying causes of death roughly mirrored those in the Finnish general population with a slight excess in mortality due to chronic respiratory diseases. Pneumonia was the immediate cause of death in just 8% of all late deaths.

Conclusions

A previous diagnosis of diabetes and newly discovered postprandial hyperglycaemia increase the risk of death for several years after community-acquired pneumonia. As the knowledge about patient subgroups with an increased late mortality risk is gradually gathering, more studies are needed to evaluate the possible postpneumonia interventions to reduce late mortality.

Strengths and limitations of the study.

Plasma glucose levels were carefully measured during pneumonia with seven plasma glucose measurements during the first day on ward.

The prospective nature of the study provided comprehensive collection of information about possible confounders.

The main limitation is the lack of validated pneumonia severity scoring although several pneumonia severity-related variables were collected.

The present population consists of patients with mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to all hospitalised patients with pneumonia.

Introduction

Pneumonia is the leading cause of infectious death worldwide with 3.2 million annual casualties.1 This figure, which is impressive enough per se, only contains acute mortality. Pneumonia is also associated with significant late mortality up to several years afterwards among patients who survive the initial episode. In a large population-based cohort study, the mortality rate was 53% at 5 years after an episode of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).2 Importantly, long-term mortality is substantially higher than that of either the general population or a control population hospitalised for reasons other than CAP.3–5 Given the high and rising incidence of CAP, its long-acting effect on mortality should be regarded as a major public health threat.6 7 It has been acknowledged that additional research is urgently needed to examine the contributors to this long-term mortality.8

Probably the most consistently identified contributor to late mortality after CAP is the presence of comorbid conditions, especially neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular conditions, malignancy and chronic obstructive lung disease.7 To the best of our knowledge, diabetes has not been investigated in this respect. Yende et al9 analysed two large CAP cohorts and found that diabetes increased the mortality rate within the first year after CAP with unadjusted HR of 1.4–1.9. They suggested that the higher mortality rate may be due to worsening of pre-existing cardiovascular disease or higher risk of acute kidney injury. However, the early and late deaths were not analysed separately and the follow-up time was relatively short.

Hyperglycaemia is associated with short-term mortality in several acute disorders including CAP.10–14 In pneumonia, a newly detected hyperglycaemia among patients without diabetes seems to increase the short-term mortality rate more than hyperglycaemia among patients with diabetes.13 The impact of new, pneumonia-associated hyperglycaemia on long-term mortality has not been investigated. The objective of the present study was to assess whether diabetes or newly discovered hyperglycaemia among patients without diabetes affects late mortality after CAP.

Methods

Study design and the population

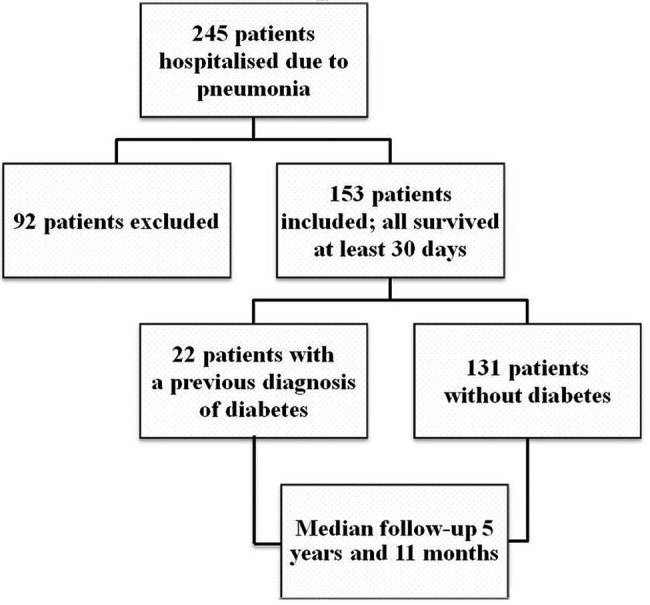

This prospective, observational cohort study was carried out at Kuopio University Hospital in Finland. From November 2006 to May 2008, all adult patients admitted to the pulmonology ward due to CAP were recruited. The patients were considered to have pneumonia if they had an acute febrile illness with a new radiographic shadowing. During that time 245 patients were hospitalised because of pneumonia (figure 1). Patients were excluded from this study if they had severe pneumonia requiring treatment in the intensive care unit, if they could not give informed consent due to confusion or if their antibiotic treatment had already been started at another institution. Altogether 92 patients were excluded and 153 patients included. All the 153 patients survived at least 30 days after admission. Among them, 22 had a previous diagnosis of diabetes (table 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion of the patients. Patients were excluded from this study if they had severe pneumonia requiring treatment in the intensive care unit, if they could not give informed consent due to confusion or if their antibiotic treatment had already been started at another institution.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patients with diabetes (N=22) | p Value* | Patients without diabetes (N=131) |

p Value† | Patients with missing data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postprandial hyperglycaemia (n=43) | No postprandial hyperglycaemia (n=88) | |||||

| Age, years | 66 (59–73) | 0.04 | 66 (60–71) | 53 (49–58) | 0.001 | 0 |

| Male gender | 68% | 0.40 | 67% | 54% | 0.16 | 0 |

| Family history of diabetes | 68% | 0.004 | 47% | 30% | 0.07 | 14 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33 (28–37) | 0.001 | 27 (25–29) | 27 (26–29) | 0.56 | 0 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 110 (102–118) | <0.001 | 100 (95–104) | 97 (94–100) | 0.27 | 18 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.83 (6.97–8.69) | <0.001 | 6.12 (5.79–6.44) | 5.64 (5.53–5.76) | <0.001 | 7 |

| Karnofsky 80% or less | 50% | 0.02 | 44% | 16% | <0.001 | 0 |

| Three or more comorbidities | 54% | <0.001 | 23% | 14% | 0.17 | 0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75 (69–81) | 0.12 | 81 (75–86) | 80 (77–84) | 0.99 | 1 |

| Heart rate, 1/min | 99 (90–109) | 0.22 | 100 (92–107) | 91 (86–95) | 0.005 | 1 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 92 (89–94) | 0.35 | 91 (89–93) | 94 (93–95) | 0.004 | 13 |

| Leucocytes, 109/L | 11.8 (9.6–13.9) | 0.46 | 12.4 (10.6–14.3) | 11.7 (10.1–13.3) | 0.10 | 0 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 6.88 (4.96–8.79) | 0.28 | 8.61 (6.41–10.8) | 4.72 (4.00–5.44) | <0.001 | 11 |

| CRP, mg/L | 164 (119–209) | 0.97 | 228 (166–289) | 146 (127–165) | <0.001 | 1 |

| Elevated NT-proBNP | 32% | 0.51 | 29% | 23% | 0.47 | 4 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 5.8 (4.6–7.1) | 0.53 | 6.6 (5.7–7.5) | 5.9 (5.2–6.6) | 0.03 | 1 |

The data are presented either as percentage of patients showing the feature or means (95% CIs).

*p Value indicates the differences between patients with and without diabetes.

†p Value indicates the differences between the patients with and without postprandial hyperglycaemia within patients without diabetes.

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C reactive protein; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c expressed as percentage of total haemoglobin; NT-proBNP, plasma N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide.

Measurements during pneumonia

During the first 24 h on the ward, the plasma glucose was determined seven times: at 3:00, before breakfast, before lunch, after lunch, before dinner, after dinner and at bedtime. In addition, family history of diabetes and the prepneumonia Karnofsky performance score were assessed. The Karnofsky score is a general measure of patient independence, which is most often utilised in patients with cancer.15 16 Height, weight, waist circumference, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, temperature and heart rate were measured. Blood tests included glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), C reactive protein, leucocytes, urea and arterial blood gas analysis.

Detailed description of the methods and the baseline results have been published.17 However, the NT-proBNP analysis will be described here for the first time. It was added to the present study since it has been shown to associate with pneumonia prognosis.18 It was measured from the blood sample collected at admission utilising a commercially available electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Elevated NT-proBNP was defined as plasma concentration above 450 ng/L for patients younger than 50 years, above 900 ng/L for patients aged 50–75 years and above 1800 ng/mL for patients older than 75 years.19

Definitions

Diabetes was defined as doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes, which had been set before the current pneumonia episode, and verified from the patient files. New hyperglycaemia was defined as hyperglycaemia during the first 24 h of pneumonia hospitalisation in a patient without a doctor's diagnosis of diabetes. Fasting hyperglycaemia was defined as hyperglycaemia detected at 3:00 or at 7:00 in the morning before breakfast. Postprandial hyperglycaemia was defined as hyperglycaemia detected during the daytime or in the evening. The cut-off values for both fasting and postprandial hyperglycaemia among the patients without diabetes were those defined by the receiver operator curves (ROC) analysis (see below). The main outcome variable was mortality from 30 days after pneumonia up to the end of follow-up. The predictor variables were diabetes, new fasting hyperglycaemia and new postprandial hyperglycaemia. A confounder was a variable that showed an association with both the plasma glucose levels during pneumonia and the late mortality. However, a potential confounder with a causal relationship to the outcome variable was not included. Furthermore, if two potential confounders were closely interrelated, the one with a closer association with the plasma glucose levels was included.

Follow-up after pneumonia

In September 2013, the survival status was obtained in all patients from the National Statistical Service of Finland. The immediate and underlying causes of death, according to the International Classification of Diseases V.10, were obtained from death certificates. The median follow-up was 5 years and 11 months.

Statistical analysis

Comparative survival curves were constructed using Kaplan-Meier methodology. The unadjusted HRs were assessed utilising univariate Cox regression analysis. Continuous data was divided to quartiles. The assumption of proportional hazard was checked by graphically comparing the hazard curves. To determinate the adjusted HRs for diabetes, new fasting hyperglycaemia and new postprandial hyperglycaemia, Cox multivariate regression analysis with backwards directed stepwise procedure was utilised. In this analysis patients with missing data were excluded.

The analysis of the effect of new hyperglycaemia was restricted to the 131 patients without diabetes. Among them, ROC curves were produced for both fasting and postprandial plasma glucose values to define the best cut-off values to predict death during the follow-up.

Frequency comparison was performed by χ2 test. Student t test and Pearson correlation coefficient were utilised when appropriate. Categorical data is expressed as percentages and continuous data as means and 95% CI. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of <0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS V.19.0 for the personal computer (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Univariate analysis and the ROC analysis

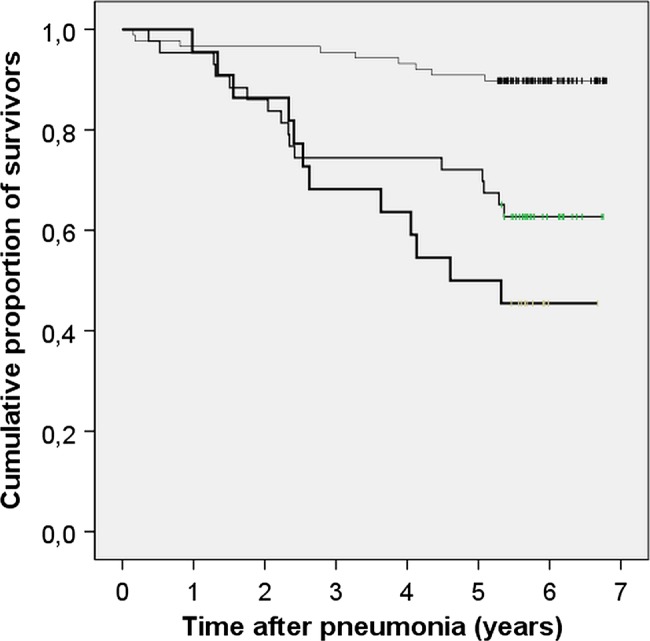

Table 1 shows the numbers of patients in each subgroup and their characteristics. The following features showed a statistically significant association with late mortality within the whole population: Presence of diabetes (HR 3.5 (1.7–6.9), figure 2), advanced age, Karnofsky score equal to or less than 80%, presence of three or more comorbidities, low diastolic blood pressure, low arterial blood oxygen saturation, high urea, NT-proBNP above predicted value,19 high HbA1c and long hospital stay (data not shown). The proportional hazards remained constant over time.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing long-term survival after community-acquired pneumonia among patients with diabetes (N=22, the bottom line), patients without diabetes with new postprandial hyperglycaemia (N=43, the middle line) and patients without diabetes without postprandial hyperglycaemia (N=88, the top line). p<0.001 between the groups.

Among the patients without diabetes, the ROC analysis of the fasting plasma glucose measurements revealed that the level of 7.05 mmol/L was the best cut-off value to predict late mortality (results not shown). A glucose level exceeding it showed an unadjusted HR of 2.7 (1.1–6.4; p=0.027). Fifty-two per cent of patients without diabetes showed a fasting glucose level exceeding 7.05 mmol/L. In one patient, no fasting glucose values were obtained. The ROC analysis of the postprandial glucose measurements revealed that the level of 10.75 mmol/L was the best cut-off value (results not shown). The corresponding unadjusted HR was 4.2 (1.9 to 9.6; p=0.001, figure 2). Thirty-three per cent of patients without diabetes showed a postprandial glucose level exceeding 10.75 mmol/L. Utilising these plasma glucose cut-off values among the 22 patients with diabetes, it could be shown that 19 of them (86%) showed fasting hyperglycaemia and 18 (82%) showed postprandial hyperglycaemia.

Multivariate analysis

The following confounders were included: Age, Karnofsky score equal to or less than 80%, elevated plasma NT-proBNP and plasma urea concentration. The results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis are shown in tables 2 and 3. It can be seen that a diagnosis of diabetes among the whole population (table 2) and new postprandial hyperglycaemia among the population without diabetes (table 3) showed independent associations with late mortality after pneumonia. New fasting hyperglycaemia was not a predictor of mortality when the confounders were taken into account (p=0.74).

Table 2.

Cox multivariate regression analysis with backward directed stepwise procedure about the effect of diabetes on the risk of late death after pneumonia

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 2.84 | 1.35 to 5.99 | 0.006 |

| Karnofsky equal or less than 80% | 4.19 | 1.86 to 9.46 | 0.001 |

| Age, years | 1.53* | 1.00 to 2.34 | 0.048 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 1.78* | 1.20 to 2.64 | 0.004 |

The included confounders were age, Karnofsky score equal or less than 80%, elevated plasma NT-proBNP, and plasma urea concentration. Only factors with at least suggestive independent association (p<0.10) with the risk of late death are presented. N=142 (1 patient with and 10 patients without diabetes were excluded due to lack of urea measurements).

*HR is expressed per quartile.

Table 3.

Cox multivariate regression analysis with backward directed stepwise procedure about the effect of new postprandial hyperglycaemia on the risk of late death after pneumonia

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New postprandial hyperglycaemia | 2.56 | 1.04 to 6.32 | 0.041 |

| Karnofsky equal or less than 80% | 3.26 | 1.12 to 9.47 | 0.030 |

| Age, years | 1.97* | 1.14 to 3.39 | 0.015 |

The included confounders were age, Karnofsky score equal to or less than 80%, elevated plasma NT-proBNP and plasma urea concentration. Only factors with at least suggestive independent association (p<0.10) with the risk of late death are presented. N=131, only the patients without diabetes were included.*HR is expressed per quartile.

The mortality rates and the causes of death

The mortality rates at the end of follow-up were 54%, 37% and 10% among patients with diabetes, patients without diabetes with new postprandial hyperglycaemia and patients without diabetes without postprandial hyperglycaemia, respectively (p<0.001). The underlying causes of death are shown in table 4. The immediate causes of death mirrored the underlying causes. Pneumonia was the immediate cause of death in just three cases (8% of all deaths).

Table 4.

The underlying causes of late death

| Group | Cancer (%) | Cardiovascular (%) | Obstructive lung diseases (%) | Miscellaneous (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No diabetes, no postprandial hyperglycaemia (9 deaths) | 2 (22) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) |

| No diabetes, with postprandial hyperglycaemia (16 deaths) | 1 (6) | 4 (25) | 7 (44) | 4 (25) |

| Diabetes (11 deaths) | 3 (27) | 6 (54) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) |

| All patients (36 deaths) | 6 (17) | 14 (39) | 7 (19) | 9 (25) |

Discussion

The present study confirms that both the pre-pneumonia health status and the severity of pneumonia are associated with the late mortality after CAP.7 In particular, the weight of low functional status was highlighted by the strong association between low Karnofsky score and late mortality. These features were taken into account in the present study. It showed that a pre-pneumonia diagnosis of diabetes is associated with a threefold increase in the risk of death up to 6 years after mild-to-moderate CAP. The study thus corroborates and extends the findings of Yende et al9, who reported of increased mortality rates in patients with diabetes up to 1 year after pneumonia. The present study also demonstrated that new postprandial hyperglycaemia among patients without diabetes shows an independent association with late mortality after pneumonia. Such an association has not been described earlier.

In acute illnesses, complex mechanisms involving hormones and cytokines lead to hyperglycaemia, which is mainly caused by excessive hepatic glucose production and manifested by high-fasting glucose values.12 This probably explains our finding that fasting hyperglycaemia was more common than postprandial hyperglycaemia among patients without diabetes. As fasting hyperglycaemia was not an independent predictor of mortality in the present study, it may be regarded as an adequate body response to infection. Postprandial hyperglycaemia, in turn, is considered as the first step in the deterioration of glucose homoeostasis.20 In the present study, the survival curves of the patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes with postprandial hyperglycaemia were almost identical up to 2.5 years. There is evidence suggesting that postprandial hyperglycaemia is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, retinopathy, renal failure and neurological complications in individuals with as well as individuals without diabetes.20 Excess late mortality after CAP can now be added to that list.

One may suspect that the hyperglycaemic patients without a previous doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes may actually have suffered from diabetes without knowing it. HbA1c reflects mean blood glucose levels during the previous 2–3 months and can be used to diagnose diabetes.21 It is true that the HbA1c values were higher in the patients without diabetes, but with new postprandial hyperglycaemia than in those without it. However, the 95% CI of their HbA1c values was below 6.5%, which is considered diagnostic for diabetes21 and also well below the HbA1c values of patients with diabetes. In addition, the patients with new postprandial hyperglycaemia did not differ from the euglycaemic patients without diabetes with respect to family history of diabetes, body mass index or waist circumference. On the contrary, the patients with a doctor's diagnosis of diabetes clearly differed from the rest of the population by showing all these typical features of type 2 diabetes.22 Therefore, most of the patients with CAP with new postprandial hyperglycaemia probably did not have an undiagnosed diabetes before pneumonia. This supports the view that stress hyperglycaemia and diabetes are two separate disorders.12 17 23

The commonly used plasma glucose cut-off values for transient hyperglycaemia during illness (stress hyperglycaemia) have been adopted from the diabetes diagnostics (fasting glucose >6.9 mmol/L or random glucose >11.1 mmol/L).12 To our knowledge, they have not been validated in stress hyperglycaemia. As mentioned, diabetes and stress hyperglycaemia are two separate disorders. The present material gave an opportunity to define plasma glucose cut-off values that best predicted late mortality among the patients without diabetes: 7.05 mmol/L for fasting glucose and 10.75 mmol/L for postprandial glucose. Our values were surprisingly close to those adopted from diabetes diagnostics and thus support their use also among patients without diabetes, but with stress hyperglycaemia. Utilising the cut-off values from the diabetes diagnostics would not have changed the results of the present study.

The present paper provides some new information on how to identify patients at increased risk of death late after CAP. However, it is not known whether the identification of such patients can influence their long-term prognosis. Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccination after CAP may be of limited value since just 8% of all late deaths were caused by pneumonia in the present study. This is in accordance with a larger study in which just 6% of short-term survivors from CAP finally died of pneumonia.5 The underlying causes of death in the present population roughly mirrored those in the Finnish general population24 with one exception: In the general population, the proportion of a chronic lung disease as the underlying cause of death is 4% but in the present population it was 19%. The aforementioned Dutch study reported exactly the same finding with much higher numbers of deaths.5 This may be due, at least partly, to patients with obstructive lung diseases being prone to catch CAP and prone to be hospitalised in case of CAP.25

If the possibilities for secondary interventions are to be established, the focus should perhaps be in the primary prevention of pneumonia. The present study suggests that Pneumococcus vaccination should be focused on patients with diabetes, aged patients and those with low performance status, among other groups previously reported to show an excessive long-term mortality after pneumonia.7 26

The main strength of the present study was the careful method used to detect hyperglycaemia during pneumonia, with seven plasma glucose measurements during the first day on ward and also the inclusion of night-time measurements. Most previous studies of the effects of hyperglycaemia on pneumonia prognosis are handicapped by the small number, usually one, of plasma glucose measurements. Plasma glucose levels vary markedly within a day during an acute illness and a single measurement can easily miss the highest values.17 23 Frequent glucose measurements explain the higher prevalence of new hyperglycaemia in the present study compared with previous ones.10 11 The prospective nature and comprehensive collection of information about possible confounders may also be considered as strengths.

The main limitation of the present study was the lack of validated pneumonia severity scoring. The management of the present patients was based on local guidelines. The Finnish pneumonia guidelines did not suggest the use of a validated severity score until autumn 2008,27 that is, after the present patient population had been collected. The lack of systematic recording of respiratory rate precludes the calculation of any validated severity scores afterwards. However, many severity-related variables like oxygen saturation, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, C reactive protein, leucocytes, urea and arterial blood gas analysis, were recorded. The population did not include patients who were confused and patients who needed treatment in intensive care unit. The present population thus consists of patients with mild-to-moderate CAP. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to all hospitalised patients with pneumonia. The relatively small number of patients and deaths may also decrease the generalisability of the results.

In conclusion, a previous diagnosis of diabetes and newly discovered postprandial hyperglycaemia may increase the risk of death for several years after CAP. As the knowledge about patient subgroups with an increased late mortality risk is gradually gathering, more studies are needed to evaluate the possible post-pneumonia interventions to reduce the late mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the nurses on the respiratory medicine ward of Unit of Medicine and Clinical Research, Kuopio University Hospital, for measuring the plasma glucose values.

Footnotes

Contributors: HOK has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. He has written the article and is the guarantor. PHS has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. She has revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. JR has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. He has revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. LN has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. He has revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The study was mainly funded by the Hospital District of Northern Savo.

Competing interests: PHS has received funding from Finnish Anti-Tuberculosis Association Foundation and Pulmonary Foundation in Kuopio Area.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed by the Research Ethic Committee, Hospital District of Northern Savo (75//2006) and it was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down on the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death 2011. Secondary The top 10 causes of death 2011 2013. http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ (access 16 May 2014).

- 2.Johnstone J, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, et al. Long-term morbidity and mortality after hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:329–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koivula I, Sten M, Makela PH. Prognosis after community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: a population-based 12-year follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1550–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan V, Clermont G, Griffin MF, et al. Pneumonia: still the old man's friend? Arch Intern Med 2003;163:317–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruns AH, Oosterheert JJ, Cucciolillo MC, et al. Cause-specific long-term mortality rates in patients recovered from community-acquired pneumonia as compared with the general Dutch population. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:763–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewig S, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia as an emergency: time for an aggressive intervention to lower mortality. Eur Respir J 2011;38:253–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo MI, Faverio P, Anzueto A. Long-term prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26:151–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortensen EM. Potential causes of increased long-term mortality after pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2011;37:1306–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yende S, van der Poll T, Lee M, et al. The influence of pre-existing diabetes mellitus on the host immune response and outcome of pneumonia: analysis of two multicentre cohort studies. Thorax 2010;65:870–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinzel T, Smith M. Hyperglycemia as a predictor for mortality in veterans with pneumonia. Exp Aging Res 1988;14:99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Blitz S, et al. The relation between hyperglycemia and outcomes in 2,471 patients admitted to the hospital with community-acquired pneumonia. Diabetes Care 2005;28:810–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 2009;373:1798–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rueda AM, Ormond M, Gore M, et al. Hyperglycemia in diabetics and non-diabetics: effect on the risk for and severity of pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect 2010;60:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepper PM, Ott S, Nuesch E, et al. Serum glucose levels for predicting death in patients admitted to hospital for community acquired pneumonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344: e3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemoterapeutic agents in cancer. In: Macleod CM, ed. Evaluation of chemoterapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press, 1949:191–205 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yates JW, Chalmer B, McKegney FP. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky performance status. Cancer 1980;45:2220–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salonen PH, Koskela HO, Niskanen L. Prevalence and determinants of hyperglycaemia in pneumonia patients. Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruger S, Papassotiriou J, Marre R, et al. Pro-atrial natriuretic peptide and pro-vasopressin to predict severity and prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia: results from the German competence network CAPNETZ. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:2069–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:330–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerich J. Pathogenesis and management of postprandial hyperglycemia: role of incretin-based therapies. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:877–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36:S11–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noble D, Mathur R, Dent T, et al. Risk models and scores for type 2 diabetes: systematic review. BMJ 2011;343:d7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskela HO, Salonen PH, Niskanen L. Hyperglycaemia during exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Respir J 2013;7:382–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Statistical Service of Finland. The causes of death 2012. https://tilastokeskus.fi/til/ksyyt/2012/ksyyt_2012_2013-12-30_tie_001_fi.html (access 16 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farr BM, Sloman AJ, Fisch MJ. Predicting death in patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:428–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blasi F, Mantero M, Santus P, et al. Understanding the burden of pneumococcal disease in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Care Guidelines Group: Treatment of pneumonia [Finnish]. Duodecim 2008;124:2030–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.