Abstract

Objectives

To examine the handling system for patient complaints and to identify existing barriers that are associated with effective management of patient complaints in China.

Setting

Key stakeholders of the handling system for patient complaints at the national, Shanghai municipal and hospital levels in China.

Participants

35 key informants including policymakers, hospital managers, healthcare providers, users and other stakeholders in Shanghai.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Semistructured interviews were conducted to understand the process of handling patient complaints and factors affecting the process and outcomes of patient complaint management.

Results

The Chinese handling system for patient complaints was established in the past decade. Hospitals shoulder the most responsibility of patient complaint handling. Barriers to effective management of patient complaints included service users’ low awareness of the systems in the initial stage of the process; poor capacity and skills of healthcare providers, incompetence and powerlessness of complaint handlers and non-transparent exchange of information during the process of complaint handling; conflicts between relevant actors and regulations and unjustifiable complaints by patients during solution settlements; and weak enforcement of regulations, deficient information for managing patient complaints and unwillingness of the hospitals to effectively handle complaints in the postcomplaint stage.

Conclusions

Barriers to the effective management of patient complaints vary at the different stages of complaint handling and perspectives on these barriers differ between the service users and providers. Information, procedure design, human resources, system arrangement, unified legal system and regulations and factors shaping the social context all play important roles in effective patient complaint management.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores the handling system for patient complaints in China and the views of key stakeholders on the barriers to effective complaint management. These findings are essential to improve the complaints system.

Our study provides a new dimension of understanding the complaint management system in China, an emerging market country.

We explore the barriers through in-depth interviews with almost all stakeholders, not only health professionals. What we found will help develop procedures for more effective complaint management and to further improve the quality of care in China and other developing countries.

The selection of participants may introduce some bias to our studies. Owing to our focus on the hospital, there may be an under-representation of certain types of respondents.

Background

In recent years, patient complaints around the world have garnered mounting concern among policymakers, academics and the general public.1–3 As China prospers, making advances in medicine and social welfare, expectations of better quality of care continue to grow. People's knowledge of the law and their rights have increased as a result of better education and understanding of the law. Patients are able to express their discontent by lodging complaints such that the number of complaints occurring internationally are on the rise.4 5 A ‘complaint’ is defined as the behaviour of a patient or his/her representative(s) that signifies dissatisfaction towards medical services, nursing services, as well as treatment conditions through letters, calls or visits to the hospital where the purpose of these actions is to criticise the hospital and/or claim compensation.6 In addition, the growth in dollars paid on malpractice claims is evident.7 China's current situation reveals growing concerns surrounding hospital accountability and clinical governance; in particular, the efficacy of the redress system. Grave consequences affecting both social and political stability are likely if the healthcare system fails to meet expectations and to achieve patient satisfaction. Indeed, the issue at hand is one of paramount importance, requiring urgent attention and immediate action at the highest level.

In countries such as Australia and Britain, the states have sought to monitor complaints and complaint handling to improve and regulate the practice of health professionals.8 A feedback system of this sort has proven instrumental in improving the quality of care. In Britain, the National Health Service (NHS) has not only provided clear and transparent guidelines for healthcare providers and patients but has also publicised information regarding the routine reporting of patient complaints.9 In Australia, a large study was conducted before Guide to Complaint Handling in Health Care Services was formulated and subsequently updated.10 Annually, statistics are compiled and published, detailing complaint trends, complaint management and reasons for complaints. Effective handling of complaints has been known to reduce friction between providers and consumers, with the even greater benefit of improving quality of care. As a supplement to peer reviews and administration, patient complaints can provide important feedback concerning the delivery of healthcare services and can be a useful tool in the improvement of healthcare quality.1–3 11–14

With no official statistics of patient complaints available in Chinese records, we estimated that the number of complaints and disputes rose, from 10 249 to 13 875 claims, based on the number of first trials for medical malpractice cases between 2002 and 2008.15 Mounting dissatisfaction has been felt across the country, manifesting in increasingly hostile and violent behaviour towards providers from patients and their families.16 An investigation carried out by the Chinese Hospital Management Association in 2005 suggested that of 270 hospitals surveyed, 73% experienced abuse in the form of threats and assaults targeting doctors and management.17 These incidents are only indicative of rising expectations, burgeoning patient discontent with services and dissatisfaction towards the way in which matters are resolved.18 Public outcry only exacerbates the need for more effective handling of individual cases under the overarching agenda of public hospital reform in China.19

Notwithstanding the alarming extent of these issues, few attempts have been made to formally examine how hospital complaints are addressed in developing countries. It is only recently that a handful of studies in China have sought to provide some understanding of the issue by trying to ascertain the number of complaints in the studied hospitals or garnering patient feedback via questionnaires and interviews.20–22 A fuller understanding of the complaints system—the available channels for seeking redress, how the system operates and the barriers to conflict resolution—will be crucial to ameliorating the often fraught relationships between healthcare providers and consumers. The purpose of this study has been to examine the handling system for patient complaints in China, and to subsequently identify and analyse the various hospital-specific factors preventing grievances from being effectively addressed. The authors of this paper hope that such an undertaking will reduce malpractice and, above all, improve health service outcomes.

This study is one of the cases from the ‘Health System Stewardship and Regulation in Vietnam, India and China’ (HESVIC) research project. It was conducted by a consortium of six partners in Asia and Europe from 2009 to 2012, with the aim of supporting policy decisions in the application and extension of accessibility, affordability, equity and quality of coverage of maternal healthcare in the three countries.

Methods

Study design

The project uses a multidisciplinary approach, drawing on multiple case studies to examine the impact of regulation on improving equitable access to quality healthcare in Vietnam, India and China. In each country, three cases were selected and studied. This paper shows the findings from the case study, examining the regulation on Grievance Redressal in Shanghai, China. Here, regulation encompasses the formation of rules and practices, as well as their interpretation and implementation, such as the health policy processes covered in the HEPVIC project.23

Phase 1: Literature review

First, we conducted a literature review. The relevant sources, which included regulation documents related to the handling of patient complaints at both the national and Shanghai municipal levels, were used to collect legal approaches and mechanisms used in managing patient complaints. These regulations were mainly stipulated from 2002 to 2011. To understand the application of different complaint approaches, a search of scientific literature published between 2000 and 2011 was conducted. Databases MEDLINE-PubMed and WANFANG Data were consulted. A search strategy was established based on the following keywords: grievance redressal, patient complaint, health care complaint and hospital complaint, and China. Special focus was placed on patient complaint management in hospitals, as we found that the vast majority of complaints were handled and resolved within the hospitals.22

Phase 2: Pilot study—interviews

Based on our understanding of the current patient complaint handling system, we performed semistructured interviews with key stakeholders—policymakers from the national level, administrators from the Shanghai municipal level, hospital managers, healthcare providers, users and other related parties. We used the snowball sampling method to identify key stakeholders and to collect important feedback from key informants from various disciplines.24 25

In phase 2 (October–December 2010), one key actor from each of the three administrative levels was selected and interviewed: a policymaker at the national level, a municipal administrator and a hospital manager. A pilot study was conducted to test the topic guidelines developed. These allowed us to gain a preliminary understanding of the complaint management process in the hospital setting, and to refine the data collection tools. These interviews served as the basis for the design of phase 3 interviews, where some of those being interviewed in the third phase were respondents recommended by phase 2 interviewees.

Phase 3: Main data collection

Interviews in phase 3 were conducted from August to December of 2011. Key stakeholders were interviewed in the selected hospitals based on location, level and type. Our sample represented both urban and suburban areas in Shanghai. General and specialist hospitals were selected. Phase 3 began with interviews of hospital managers and healthcare providers proposed in phase 2. We asked interviewees from phase 2 to invite patients and other relevant stakeholders to contribute their views. Those invited patients used different channels for lodging their complaints; however, they all shared one thing in common: all patients had first complained to the hospital. We then proceeded to interview the administrators and finally a high-level policymaker. We continued to interview respondents, collecting and analysing their comments and feedback until no new themes emerged, that is, saturation had been reached. The number of participants involved in the different types of interviewees is depicted in table 1.

Table 1.

Number of interviewees by administrative level and facility

| Types of interviewees | Level | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Policymakers | National | |

| Ministry of Health | 1 | |

| A university | 1 | |

| Administrators | Shanghai municipal | 4 |

| Hospital managers | ||

| General hospital | Tertiary | 3 |

| General hospital | Secondary | 3 |

| Specialised hospital | Tertiary | 1 |

| Specialised hospital | Secondary | 1 |

| Private hospital | Secondary | 2 |

| Healthcare providers | 6 | |

| Users | 6 | |

| Other actors | ||

| Municipal Health Inspection Institute | 2 | |

| Lawyers for medical disputes | 2 | |

| The centre that processes medical liability insurance | 1 | |

| The People's Mediation Committee for Medical Disputes | 1 | |

| The Complaint Letters and Visits System | 1 | |

| Total | 35 | |

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 35 respondents face-to-face, except one via telephone. The interviews took place at private locations, for example, at the institution where the interviewee or interviewer worked, and were conducted by two of the authors of this paper. Each interview lasted for 1–2 h and was audiotaped with permission, apart from two which were not recorded but typewritten on the respondents’ request.

The topic guidelines for carrying out the interviews included questions on the participant's experience in complaint management in the hospitals. Using probes and follow-up questions, attention was directed to factors that the interviewees perceived as barriers to effective complaint management, and interviewees were asked to explain their reasoning. From the existing literature, we identified a list of factors required for effective complaint management and successful resolution of disputes. Participants were asked to provide suggestions and feedback regarding how complaints could be more effectively dealt with given the barriers they had identified.

Data analysis

Audiotapes recorded during the interviews were transcribed and were compared with the field notes to check for accuracy. We analysed data through a process of rigorous and structured analysis.26 The analysis was executed in several stages to (1) become familiar with the data; (2) identify emerging topics; (3) develop a topic index; (4) use the index to code the data; (5) consolidate the topics into themes; (6) further consolidate these themes into analytical categories/clusters and (7) translate the analysis obtained into a narrative. Written consent was obtained from each interviewee before undertaking the interviews.

We performed the above tasks using the qualitative research software NVivo V.9.0. The raw data were coded by two independent reviewers (YJ and QZ). If discrepancies emerged, a third reviewer (XY) participated in the group discussion until the group arrived at a consensus. There were some models for analysing complaint management2 13; for example, the Managerial-Operational-Technical model was developed by Hsieh SY to explore complaint management in hospitals.2 In our study, we collected data according to the complaint management process. To analyse the data most efficiently and directly, we used the stages of the process, which included receiving, handling and resolving complaints.27 As quality improvement following complaints is crucial, we added the stage of “institutional changes for quality improvement using complaints data.”2 12

Access to data was restricted to approved members of the research team who signed a confidential agreement with the principal investigator. Data were stored in secure electronic locations. Data processing was kept anonymous so as to protect the identity of interviewees. The names of the respondents have been deleted from the quotations.

Findings

This section first presents a number of approaches developed and implemented in Shanghai to handle patient complaints and their relationships. It then focuses on the approach of negotiation between hospitals and complainants, identifies its barriers and proceeds to examine and analyse these barriers.

Approaches and mechanisms used in managing patient complaints

The study identifies both formal (table 2) and informal approaches and mechanisms used in handling patient complaints.

Negotiation between hospitals and complainants

Table 2.

The characteristics of the formal approaches

| Negotiation between Hospitals and Complainants | Administrative Mediation | Civil Lawsuits | Complaint Letters and Visits System | People's Mediation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible institution | Complaint Reception Office in hospitals | Health Inspection Institute | People's Court | Complaint Letters and Visits Office in health administrative departments | People's Mediation Committee for Medical Disputes |

| Responsibility | Receive and handle patients’ complaints; compensate some complainants | Receive and mediate medical malpractices | Receive and settle medical litigations | Receive, transfer and supervise patients’ complaints | Receive and mediate patients’ complaints |

| Handling method | Negotiation | Mediation | Mediation; trial | Supervise matters | Mediation |

| Processing duration | Indefinite | Only once | 6 months | 2 months | 1 month |

| Legal level of resolution | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Administrative level of resolution | Low | High | High | High | Low |

The complaint handling department within the hospital is responsible for dealing with patient complaints and was first established on 20 February 2002, in accordance with the Regulation on the Handling of Medical Malpractices.28 Since November 2009, these departments have been regulated by Measures for the Handling of Patient Complaints in Hospitals (for Trial Implementation).6 These acts require that a medical institution establish a department specifically for the purpose of handling and resolving medical disputes. The department is primarily responsible for receiving patient complaints via calls, letters, visits and/or cases referred from other departments and institutions. Their role also includes counselling and communicating with patients, verifying and documenting disputes as well as resolving disputes.

Administrative mediation and civil lawsuits

If the hospital is unable to resolve certain conflicts through negotiation, the cases may be referred to an external body such as the health administrative department or they may be settled in court by means of litigation. The Tort Law of the People’s Republic of China, adopted at the 12th session of the Standing Committee of the Eleventh National People’s Congress on 26 December 2009, provided a new legal definition of liability for medical malpractice, liability presumption and exemption.29

Complaint Letters and Visits System

In February 2007, Measures for the Complaint Letters and Visits System for Healthcare was established.30 Its purpose is to protect the legal rights and interests of citizens, legal entities and other organisations, and to regulate behaviour and maintain order within the Complaint Letters and Visits System. It requires health administrative departments to set up Complaint Letters and Visits offices at different levels. These offices are responsible for receiving, assigning and transferring matters as appropriate, as well as supervising the handling of various issues and complaints.

People's Mediation—a form of Third-Party Facilitated Mediation

In July 2008, the Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau issued Opinions on Regulating People’s Mediation Organizations to Participate in Medical Dispute Mediation, to establish the People's Mediation Committees for Medical Disputes.31 Committee members, mainly retired judges and doctors, served to mediate disputes through reporting, explaining and analysing cases under the supervision of the local judiciary. In January 2010, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Health and the China Insurance Regulatory Commission jointly issued Opinions on Strengthening People’s Mediation for Medical Disputes to bolster the role of mediation in resolving medical disputes.32 Its intent is to settle medical disputes in an effective way and to maintain order within hospitals, all with a view to ensuring harmony and social stability. In July 2011, the Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau introduced Measures on People's Mediation for Medical Disputes in Shanghai to replace Opinions on Regulating People’s Mediation Organizations to Participate in Medical Dispute Mediation.31 33

In addition to the aforementioned channels of complaint, patients have also been found to express their discontent by “Yi Nao”—exhibiting disruptive behaviour within the hospital by targeting doctors and nurses or hospital managers by way of abuse, assault and other forms of violence. Much of this has garnered media attention, resulting in bad publicity for the hospital and damaging the reputation of doctors and staff.

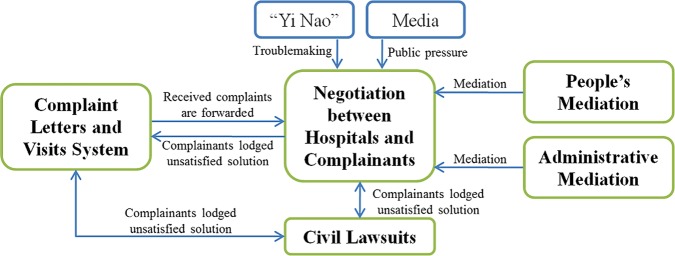

The application of different complaint approaches

The complexity of relationships between different approaches can be seen where many actors are involved. The responsible institutions of all approaches can receive complaints. Generally speaking, patients first lodge complaints to hospitals. If complainants or hospitals are unwilling or fail to negotiate, they may file applications to other approaches. Approaches that can resolve medical disputes are mainly negotiations and civil lawsuits, while other approaches play a part in forwarding cases, such as Complaint Letters and Visits System, or easing conflicts, such as mediation. None of the approaches are considered the ultimate arbiter. For example, patients can continue to lodge complaints through the Complaint Letters and Visits System even if a decision has been finalised after a second trial in court or after negotiations with hospitals.

In the aforementioned approaches, the hospital is the main handler for patient complaints. First of all, it can handle patient complaints completely independently, from reception to solution, while the other approaches, such as the Complaint Letters and Visits System and mediation, must engage hospitals in complaint handling. Second, since the hospital is principally responsible for compensation, the complainant is more inclined to directly negotiate with the hospital. Findings from the literature show that the majority of medical disputes are resolved by negotiation between hospitals and complainants.22 Third, if hospitals handle complaints improperly, conflicts will become more volatile, resulting in serious incidents, such as “Yi Nao”.34 Therefore, hospitals have become the most common receiver, handler and resolver of disputes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The structure of managing patient complaints in china.

Barriers to the effective management of patient complaints and their underlying causes at different stages

Our interviews revealed that different hospitals often use different complaint systems. For example, some hospitals operate a centralised complaints office that may or may not be independent of the Medical Affairs (Administration) Department. Other hospitals have several complaints offices, each of which is responsive to different kinds of complaints. A hospital's deputy director, who also heads hospital complaint management, generally manages complaint departments. Barriers to effective complaint management vary at different stages of the complaint process, both from the sides of the user and provider.

A. Barriers to receiving the complaints

Low awareness of users about the handling system for patient complaints: Although hospital staff claimed that the complaints office was accessible to those with grievances, patients did not always feel this was the case. One user looked up the hospital telephone number on the internet and said the complaint handling process was ‘very easy’ while others did not concur. Almost all the patients interviewed found that signs and directions (to the complaints office) failed to catch the eye. In some cases none could be seen at all:

I wanted to lodge a complaint, but did not know how to find [the complaints office]…Because the hospital was so big, I did not know which department [was responsible for handling complaints]…I simply did not know who to turn to. You see, the complaints department was in another building [rather than in the one in which I was treated i.e. the clinical department] (Female, Users-1, 01-09-2011)

Barriers to handling the complaints

Poor capacity and skills of healthcare providers: The capacity and skills of healthcare providers in managing patient complaints is critically important in problem solving. Our study found that the reasons patients complained lay mainly in poor communication and factors such as the provider's attitude, use of language, unprofessional behaviour, as well as dissatisfaction towards service procedures.

The Medical Doctors Association carried out a survey on the nature of medical disputes. 50 per cent of cases were results of inappropriate attitudes about health care delivery, 25 per cent were caused by technology misuse and the rest were related to management. (Female, Policy makers-1, 16-12-2010)

The majority of complaints can be resolved by an explanation issued by the hospital and/or a verbal apology by the offending party.5 35 36 However, practitioners are often too preoccupied with their clinical duties to be able to respond to patient complaints.

Doctors are not able to devote much time to handling disputes, because clinical work is highly demanding. [They need to attend to] many patients every day. If they spend more time communicating with patients, they would lose time needed to carry out [clinical work]. That is to say, [doctors should be given] less [clinical] work, and more time to explain their work to patients. Our workload is very heavy, like a battle. (Female, Health care providers-1, 01-09-2011)

Incompetence and powerlessness of complaints handlers: In comparison to healthcare providers, complaint handlers played a more important role in cooperation and coordination. Although complaint departments were specifically set up in hospitals for receiving and handling complaints, the responsible persons in the department were mainly part-time medical staff. In some cases those handling staff were found to be inadequate due to lack of training. Many of them had studied handling techniques on their own and had not acquired sufficient professional skills to appropriately analyse, assess and solve complaints.

Complaint handlers in the hospitals cannot solve everything because the disciplines involved in complaints are highly specialised. I am only familiar with general surgery and issues that require common sense, but [I am not familiar] with professional problems in other disciplines. (Male, Hospital managers-5, 08-09-2011)

It is difficult to recruit staff for our Medical Dispute Handling Office. No one wants to come. A boy recruited in 2007 could not stand the demands of the job [complicated disputes and violence] and so resigned. (Female, Hospital managers-3, 31-08-2011)

We have little time to do things other than receiving complaints. We lack staff members. We are responsible for receiving and processing complaints, and expected—on top of this—to deal with other things, hence why we are exhausted. (Male, Health care providers-2, 16-09-2011)

Given that most complaints are handled and resolved in the hospital, it appeared that every complaint handler interviewed felt the same way: tired and stressed. Complaint handlers were insufficiently empowered to handle complaints. It was hard for them to coordinate between different departments, investigate cases, organise mediation, find solutions and then draw on patients’ feedback to improve quality of care.

Recently, a fierce medical dispute occurred because of a possible misunderstanding between administrative departments. [Abusive] words erupted. As a consequence, staff members involved in this incident were distraught—to the extent that they wanted to resign. Hence, we need understanding and support among colleagues…Sometimes the clinical department at hand refused to cooperate when investigated. He [the clinical department] is not very serious about cooperating with the investigation. (Female, Hospital managers-3, 31-08-2011)

Communication between administrative departments and clinical departments is not very effective sometimes. I am not satisfied with this. (Female, Hospital managers-2, 25-08-2011)

Non-transparent exchange of information: In addition, the complaint handling process was not truly open to the complainant, and information exchange was largely limited to hospital staff. In fact, it was found that the staff at the complaints office was generally evasive towards patients who arrived wishing to be updated with the specifics of their complaint. Complainants had no opportunity to directly engage in the handling of their complaints or to meaningfully participate in the process. In addition, hospitals tended to oversimplify cases, assuming that the complainant's only desire was to report their complaint and ask for compensation. This implies that the entire handling process is disclosed only among hospital staff. Therefore, the process becomes a ‘black box’ to patients. It is easy for the hospital to manipulate a complainant by providing limited information to gain advantage in negotiations, that is, reduce loss from compensating patients.

Sometimes you have to circumvent something and use negotiating skills. Mistakes in medical services do not necessarily harm patients’ health, but they can be very serious for the provider [...] for example, someone may not be very careful when writing a medical record and alter it by accident. But you are likely to lose a lawsuit on the grounds of having tampered with records. Incidents such as these cloud the matter, making transparency difficult. (Female, Hospital managers-2, 25-08-2011)

If the incident is urgent or presents itself as a recurring problem, it might be shared to educate healthcare providers but disclosure to complainants themselves remains limited. Only outcomes deemed to be of direct interest to patients, including compensation amounts and medical service privileges, were provided. However, other results, including penalties imposed on physicians and departments or improvements made to hospital services, were largely withheld from patients if they did not ask.

In individual cases, what are the outcomes of their complaints? How might a physician be punished/penalised/disciplined? Such information is requested by patients only occasionally. (Male, Health care providers-2, 16-09-2011)

I want to know how to better educate the concerned health care providers. But I have not been told. (Female, Users-3, 20-09-2011)

Barriers to resolving the complaints

Conflicts between relevant actors and regulations: Within the complaints system, conflicts or inconsistencies can arise between the legal system for handling complaints and the solutions determined by the hospital. As the structure of managing patient complaints is shown in figure 1, different regulations stipulate different approaches. Unified laws or guidelines do not exist to clearly illustrate the relationships between different approaches, which results in problems such as a lack of authority or ultimate approach, uncertainty about how to apply different regulations to one case, and no clear definitions or classifications with regard to patient complaints.

The current state of complaint management is disorderly. There are too many channels. For example, many departments are involved, including but not limited to Complaint Letters and Visits, online complaints, etc. The Health Bureau has two departments [for complaint management], and each district has a mediation office, a district government website or a mayor-mail [to receive complaints], and a Complaint Letters and Visits office…Far too many heads of departments within the health sector; it is chaos. (Male, Health care providers-2, 16-09-2011)

Hospitals are required to report complaints to a lot of sectors, all of which wish to understand the issue from different angles. Conflicts between regulations do not necessarily exist, but different elements are emphasised. Hospitals are tired of these kinds of bureaucracy…Each sector carries out their designated duties where resources are not shared. The information possessed by each sector is fragmented. You know yours, I know mine. (Male, Administrators-2, 18-08-2011)

Medical malpractice is defined clearly in the Regulation on Handling Medical Malpractice. There are several benchmarks determining the amount of compensation issued. After the Tort Liability Law of the People’s Republic of China was promulgated, [medical damage] was compensated for more in accordance with the Tort Liability Law because it stipulates compensation for personal injury. (Female, Hospital managers-2, 25-08-2011)

Unjustifiable complaints by patients: In some cases, the patient experiences inconvenience when receiving medical services not because of poor conduct in attitude or behaviour on the part of healthcare providers, but possibly because of long wait times, too little time spent with the doctor and/or imperfect resource allocation. These are health system issues rather than problems caused by hospitals or individual physicians. And so, to a certain extent, physicians and hospitals have become scapegoats of the entire health system.

At times it is not us physicians who make patients angry. Certain factors are rooted in the fabric of health care systems, but we physicians [end up] taking the blame. (Male, Health care providers-3, 16-09-2011)

For example, should a doctor need to see sixty patients in half a day, or indeed one hundred, you cannot demand that he puts on a smile for each one. A lot of patients complain about doctors with a straight face, but I think it is understandable. I have a very good relationship with our young doctors. They operate on a tight schedule. This week someone worked at the outpatient facility. He was friendly with patients in the first month but struggled to sustain that sort of demeanour. He is not in the mood to smile at patients or engage in long conversations when he only has time to attend to their illnesses. (Male, Hospital managers-1, 15-12-2010)

For example, dissatisfaction voiced in the hospital may be related to health insurance policy rather than staff behaviour. Hospitals need to follow the policies made by the Health Insurance Department. The purpose of those policies was to improve rational use of medicines and control healthcare costs, while the patients covered by health insurance may demand more medicines.

Chinese doctors have many rules to obey [this is to curb poor conduct]. The pressures for them to perform are relatively large. For example, doctors cannot prescribe too much medicine for a patient who has only [basic state-financed] medical insurance, but patients always want more. A while ago, the Medical Insurance Bureau issued the following statement in a newspaper: “The Medical Insurance Bureau never limits the volume of drugs prescribed, rather it is the doing of hospitals who wish to increase workload [in order to produce more statistics].” I think this is really unreasonable. The Bureau does not control the quantity of drugs prescribed in any given week, but there is a total quantity limit over a year. Doctors try their best not to prescribe drugs which must be self-financed, i.e. not covered by basic medical insurance. They must also explain very clearly before prescribing self-financed drugs, otherwise, patients will lodge complaints once they find out. (Male, Hospital managers-1, 15-12-2010)

Complaints occur when the patient wants more drugs but the doctor refuses to satisfy his or her demands. Why? The health insurance institution sets a limit on drug expenditure for each hospital; in turn, the hospital sets a limit for each doctor. So if a doctor has too many patients drawing from their health insurance scheme in any one month, he or she may very possibly have exceeded his/her limit. (Male, Health care providers-3, 16-09-2011)

[A patient who has] basic state-financed medical coverage is entitled to blood and other auxiliary examinations. If the number of health checks prescribed exceeds a certain threshold, the doctor is viewed as exploiting basic medical insurance. The doctor is consequently punished. I was deducted more than seven hundred yuan (RMB) because of a case like this. I feel this is simply absurd—it is [unexpectedly] doctors who are to blame. Nothing seems to be wrong with the patient…The hospital cannot do anything about medical insurance. I think this kind of thing is not the problem at the hospital level. The complaints about medical insurance define, without a doubt, problems underlying the state and society. (Male, Health care providers-4, 16-09-2011)

In addition, the safety of healthcare providers is under threat in China today. Chinese medical workers are often victims of violence. As a consequence, some healthcare providers have decided to not treat patients deemed likely to assault staff, exhibit disruptive behaviour or otherwise prove to be difficult. Prescribing redundant check-ups and drugs are alternatives to properly seeing to patients.

In our interviews, 15 interviewees mentioned “Chao” 55 times. “Chao” in Chinese means to argue with hospitals for patients’ rights and interests, while the other meaning is to wrangle fiercely in hospitals or with senior management. Most of the hospital staff interviewed suggested that some complainants were indeed unreasonable and impulsive with the sole purpose of claiming.

If the case goes to court, the patient gathers a lot of people to go to the court, insulting and threatening concerned health care providers and their lawyers. That is not what we want to see. We want to talk about the truth, by thoroughly publicizing the truth. We cannot always be too specific with terminology [for fear of revealing too much]. When completely refuted, patients lose their temper. (Male, Other actors-2, 15-09-2011)

I feel that the widespread situation in China today is that you can do nothing if you run into the unreasonable. The legitimate way of going about this is to propose a fair decision once I receive your complaint. If complainants are not willing to settle for this, we then transfer their case to other departments. However, complainants may not even agree to that, causing trouble and even threatening the safety of health care providers. (Female, Hospital managers-2, 25-08-2011)

The claim a complainant demands goes beyond the actual problem [but for the money] and he does not wish to resolve it the legal way…Nowadays “Yi Nao” has brought about serious social effects, and has escalated the tension between service users and providers. Complainants are unwilling to resolve things the legal way, rather, just pestering and hassling you [health care providers or complaint handlers] all day. (Male, Hospital managers-6, 01-11-2011)

Barriers to institutional changes for quality improvement using complaints data

Weak enforcement of the regulation: The regulation for managing patient complaints is merely a guideline that contains no mandatory requirements such as assessment mechanisms. Because it takes into account the difference in local conditions throughout China, specific contents were not stipulated. The regulation is to be interpreted according to local circumstances and conditions. Therefore, in the absence of strong public scrutiny, there is little accountability for how best to manage patient complaints.

There are no penalties attached to (failure to follow) regulation. For example, there is no administrative aspect to the regulatory guidelines. We wanted to write a penalty provision, but it was not based on the top legislation. The purpose of the regulation is to emphasise self-discipline and to serve as guidance for the hospital. [The penalty was not enforceable,] so we decided to remove the penalty. It is indeed difficult and contradictory. (Female, Administrators-4, 30-11-2011)

Besides the legal system, the reporting system also has its problems. Some statistics about patient complaints and medical malpractice were utilised as a part of assessments of hospital performance, healthcare quality, and so on. This meant that the more cases that were reported, the worse the evaluations received by the hospitals so that hospitals were inclined to report selectively or report fewer cases.

There are certainly no statistics for the number of patient complaints. There is only the data on the number of medical malpractice cases per year from the Bureau of Health, and an approximate amount of compensation issued by insurance companies. In some cases, if complaints were solved just between the hospital and the complainant, we have no data. (Male, Administrators-2, 18-08-2011)

These days, the information regarding the management of patient complaints in hospitals is difficult to access. Hospitals are unwilling to provide that sort of information – it is considered confidential. We only have some profiles or the information from select hospitals. (Female, Policy makers-1, 16-12-2010)

Thus, the adoption of the incentive and sanction mechanism was contradictory for managing patient complaints. From one side, the administrative department wanted hospitals to report patient complaints because it is important for informing and improving the quality of care. From the other side, the more complaints that are registered, the worse it would appear a hospital is doing. In addition to this, managing patient complaints remains low on the health reform agenda. The force for inspecting complaint management in hospitals from senior management and administrative departments remains weak.

[Having a statistic for patient complaints] is definitely necessary from the aspect of effective management. If this statistic is disposable, I think nothing of it. If the statistic is routine, in fact, it will cost [all sorts of resources]. (Male, Policy makers-2, 22-12-2011)

Hospitals doubt that the purpose of administration is for information management – to help them better handle and solve disputes. However, if you want me to report incidents but meanwhile punish me for that, then I have no incentive to report anything. This contradiction stands [in the way of effective reporting]. (Female, Administrators-4, 30-11-2011)

Deficient information system for managing patient complaints: Although the regulations in place require collecting and analysing information, there exists no clear classification, definitions or unified coding system. Most hospitals have established their own systems for recording complaints and analysing cases, but no accurate or comparable data are available.

In fact a lot of cases should be recorded and analysed, [but] we do not even take into account so-called major cases of medical malpractice, mass disturbance or medical malpractice. We cannot distinguish between these concepts…Relatively speaking, it is more feasible to publicize the data on public security, e.g. the number of police records and people arrested, and the number of crimes committed. Those definitions are more explicit, whereas those concerning complaints management are not. Because all statistics are calculated in the hospital, we find that where standards are slack, the resulting statistic is large and where standards are strict, the statistic is small. Hence, there is great variability in our results. (Male, Policy makers-2, 22-12-2011)

Identical forms are sent to two hospitals at a similar level and the reported data can be quite different…Some hospitals only reported cases resulting in compensation and some hospitals record all persons who voice a concern, while others only report cases identified as medical malpractice. But it is impossible for me to verify [the reported data] in each hospital. (Male, Administrators-2, 18-08-2011)

Hospitals have not publicised complaints; neither have health administration departments. The Shanghai Bureau of Health launched a pilot project in 2005 to publicise the complaints reported by all hospitals in Shanghai. The project was welcomed by the public but discontinued soon after its launch due to mounting pressure from the hospitals.

We already publicize complaints [medical malpractice] on our intranet for hospital staff. It is unnecessary to share this information on external sites. (Female, Hospital managers-4, 06-09-2011)

To my knowledge, such information was published once on the Xinmin Evening News in 2005. The newspaper named hospitals that had won awards and gave details of the number of medical malpractice cases happening in each, as well as feedback regarding patient satisfaction. [We felt] the pressure was very, very high. It [publishing those] resulted in public outrage [from hospitals]. (Female, Administrators-4, 30-11-2011)

Unwillingness of hospitals to effectively handle complaints: Most hospitals did not devote much effort into managing complaints. There was no clear mechanism to utilise patient complaints to improve quality of care unless serious medical malpractice had occurred or complaints were found to recur.

Hospitals just handle complaints when complaints happen…We are basically perfunctory, including hospitals, department directors and doctors. The best-case scenario for me: do not approach me for these things [complaints]. Deal with complaints quickly and efficiently; in other words, spend money to buy peace. The impact of managing and addressing complaints is negligible, with very little effect on improving medical procedures and quality. (Male, Administrators-2, 18-08-2011)

Hospital directors were the key actors of complaint management in hospitals. The incentive and sanction mechanisms in hospitals depended on how much attention directors pay to complaint management. In the 1980s the government reduced subsidies for public hospitals under the context of transforming the planned economy to a so-called socialist market in order to reduce inefficiencies in healthcare provision. Hospitals had to increase service charges to recoup the operational costs and to increase the income level of health workers. Complaint management occupied nothing but a small part of quality healthcare, so in most hospitals it failed to draw attention from senior management. Most complaints were solved on a case-by-case basis, without sufficient concern for the overall improvement of healthcare services.

In practice, the head of department influences implementation. If he/she regards this as important, then subordinates work harder of course. Now the problem is that some heads of department do not pay attention to it [complaint management]. (Male, Health care providers-2, 16-09-2011)

It is of course medical services that are the core of hospital work. Things such as [complaint management] are boring for the hospital. To a hospital, the fewer the complaints, the better. (Male, Administrators-2, 18-08-2011)

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the handling system for patient complaints in China and aired the views of key stakeholders on the barriers to effective complaint management. Our study provided a new dimension for understanding the complaint management system in China, an emerging market country. Hospitals are the most important handler and manager of patient complaints in China and similarly for other developing countries, such as India and Vietnam.22 We explored the barriers through in-depth interviews with almost all stakeholders, not only health professionals. We hope that our findings will help develop procedures for more effective complaint management and further improve the quality of care in China and other developing countries.

To reduce the heavy burden placed on hospitals, the government has tried to seek help from other approaches aside from negotiation with hospitals. Initially, those other approaches were frequently welcomed and praised, but they seemed to be ineffective and inefficient. The effectiveness and efficiency of those other approaches needs further research. The selection of participants may introduce some bias to our studies. Owing to our focus on the hospital, there may be an under-representation of certain types of respondents. Since there are no unified classifications for complaints, we did not include patients with different types of complaints. Moreover, we planned to recruit the same number of participants in multiple settings, but the number of participants from each was imbalanced because of information saturation.

We found that the three main project elements adopted from Hickson et al13 were relevant and useful for the discussion of our results: (A) organisational supports, (B) commitment from key people and (C) learning systems.

Organisational supports

Our findings showed that there are no standardised systems and procedures dealing with patient complaints in China due to conflicts between relevant actors and regulations. Having experienced rapid economic growth in the past 30 years, China is undergoing a socioeconomic transition. Like other developing countries, policies lag behind the country's economic transition.37 38 The Ministry of Health has tried to guide healthcare providers by issuing special regulations, but health administrations do not apply strict regulations to complaint management. There lacks clear relationships between patient complaints and clinical outcomes or the quality of care.

The patient complaints in many Chinese hospitals are not well managed and handled. Most hospitals manage patient complaints on only a case-by-case basis. They lack clear mechanisms linking patient complaints with improving the quality of care. Complaints are underutilised for organisational strategic planning or for changing an individual's behaviour and attitude. This implies that legislation should not only stipulate the principles and regulations of patient complaint management, but also the responsibilities of sectors at different levels.39

Commitment from people

The hospital leader is the key determinant for complaint handling inside the hospital. However, no apparent incentives exist to push hospital leaders to prioritise complaint handling. The power of complaint handling departments depends on how much the hospital leaders pay attention to it. Under current conditions, hospital leaders lack political will to manage complaints effectively, leading to inadequate human resources in complaint handling departments. The departments also lack the power to coordinate with clinical departments.

To alleviate patient complaints-related violence, civil groups, including service users and the hospital sector, should approve the guideline. In developed countries, patient complaint management provides guidelines not only for healthcare providers, but also clear guidelines for patients. This not only makes it more convenient for patients, but also plays a positive role in helping patients initiate the complaint process via legitimate means. This is crucial for society to view patient complaint in a rational way.

Learning systems

If patient complaints can be better managed and rectified, the instances of failure would be reduced and quality would be improved.40 41 Greater emphasis should be placed on quality improvement after patients complain. Strategies to improve quality following patient complaints should be developed through a learning process.42 To promote the learning process, appropriate mechanisms should be developed and implemented to assess not only the number of patient complaints occurring in hospitals, but also how these hospitals have handled the complaints. For example, reporting more patient complaints should not be necessarily punished, while effective handling of the patient complaints should be appreciated.

Our final conclusion is that barriers to the effective management of patient complaints vary at the different stages of complaint handling, from the user and provider side, as well as systemic issues. Information, procedure design, human resources, system arrangement, a unified legal system and regulations and factors shaping the social context all play important roles in effective patient complaint management. Appropriate mechanisms should be developed to link patient complaints with improving the quality of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The consortium would like to thank all the study respondents and participants for their willingness to take part in the research, as well as the members of the Country Research Advisory Groups for their support at every stage of the HESVIC project. The authors of the paper very much appreciate constructive comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the paper from Shenglan Tang from Duke Global Health Institute, USA. The authors are also grateful to Ms Kaori Sato for language editing.

Footnotes

Collaborators: HESVIC team authorship.

Contributors: YJ contributed substantially to conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article and revising it; and final approval of the version to be published. XY contributed substantially to conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article; and final approval of the version to be published. QZ contributed substantially to acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article; and final approval of the version to be published. SRT contributed substantially to analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article; and final approval of the version to be published. SK and MM contributed substantially to conception and design, and analysis and interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. XQ contributed substantially to conception and design, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. HESVIC team authorship.

Funding: This study was supported by the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (HEALTH-F2-2009-222970).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board (IRB), School of Public Health, Fudan University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sage WM. Putting the patient in patient safety: linking patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA 2002;287:3003–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh SY. A system for using patient complaints as a trigger to improve quality. Qual Manag Health Care 2011;20:343–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wofford MM, Wofford JL, Bothra J, et al. Patient complaints about physician behaviors: a qualitative study. Acad Med 2004;79:134–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beecham L. Patients’ complaints: GMC could do better. BMJ 1999;319:1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson K, Allan D, Finucane P. A 30-month study of patient complaints at a major Australian hospital. J Qual Clin Pract 2001;21:109–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health. Measures for the handling of patient complaints in hospitals (for trial implementation). Beijing: Ministry of Health, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medical Malpractice Law in the United States. http://www.kff.org/insurance/upload/Medical-Malpractice-Law-in-the-United-States-Report.pdf (accessed 31 Aug 2012).

- 8.Hsieh SY. Healthcare complaints handling systems: a comparison between Britain, Australia and Taiwan. Health Serv Manage Res 2011;24:91–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health, United Kingdom. Complaints procedure. http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/contact-dh/complaints/ (accessed 31 Aug 2012).

- 10.Cornwall A, Romios P. Turning wrongs into rights. Health Issues 2004;79:13–18 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA 2002;287:2951–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pichert JW, Hickson GB, Moore IN. Using patient complaints to promote patient safety. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, eds. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches (vol. 2: culture and redesign). Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008:421–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hickson GB, Moore IN, Pichert JW, et al. Balancing systems and individual accountability in a safety culture. In: Berman S, eds. From front office to front line: essential issues for health care leaders. 2nd edn. Oakbrook Terrace: Joint Commission Resources, 2012:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent C, Davis R. Patients and families as safety experts. CMAJ 2012;184:15–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xi X. Understanding and application of provisions in the Tort Liability Law. Beijing: Press of the People's Court, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Lancet. Chinese doctors are under threat. Lancet 2010;376:657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng XQ, Wei LY, Zhang BZ, et al. Domestic survey of medical disputes and foreign medical dispute handling. Chin Hosp 2007;7:2–4 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stafford C. Moral ambivalence in modern China. Lancet 2012;9818:793 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Communicating concern: complaints against doctors. Lancet 2013;382:1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuang Y, Zhong C, Liu J, et al. A survey and analysis of complaint management in five tertiary hospitals. Chin J Hosp Adm 2006;22:45–8 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan N, Yu T, Chen W, et al. Analysis of differences in cognition between doctors and patients and causes of medical disputes. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ (Med Sci) 2008;28:1035–7 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J, Cao W, Xu Y, et al. Survey analysis of consultation settlement for medical disputes in 30 medical institutions of Shanghai. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ (Med Sci) 2010;30:960–3 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green A, Gerein N, Mirzoev T, et al. Health policy processes in maternal health: a comparison of Vietnam, India and China. Health Policy 2011;100:167–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadler GR, Lee HC, Lim RS, et al. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci 2010;12:369–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacey A, Luff D. Qualitative research analysis. The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health, NSW. Complaint management guidelines. North Sydney, NSW: Guidelines, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.State Council. Regulation on the handling of medical malpractices. Beijing: Decree of the State Council, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Standing Committee of the Eleventh National People's Congress. Tort Law of the People's Republic of China. Beijing: Presidential Decree, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health. Measures for the complaint letters and visits system for healthcare. Beijing: Ministry of Health, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau. Opinions on regulating people's mediation organizations to participate in medical dispute mediation. Shanghai: Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Health, and China Insurance Regulatory Commission. Opinions on strengthening people's mediation for medical disputes. Beijing: Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Health, and China Insurance Regulatory Commission, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau. Measures on people's mediation for medical disputes in Shanghai. Shanghai: Shanghai Justice Bureau and Health Bureau, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan X. Correctly receive medical complaints and establish harmonious doctor-patient relationship. Mod Hosp Manag 2008;6:24–5 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manouchehri MJ, Ibrahimipour H, Sari AA, et al. Study of patient complaints reported over 30 months at a large heart centre in Tehran. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siyambalapitiya S, Caunt J, Harrison N, et al. A 22 month study of patient complaints at a National Health Service hospital. Int J Nurs Pract 2007;13:107–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grundy J, Khut QY, Oum S, et al. Health system strengthening in Cambodia—a case study of health policy response to social transition. Health Policy 2009;92:107–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luong DH, Tang S, Zhang T, et al. Vietnam during economic transition: a tracer study of health service access and affordability. Int J Health Serv 2007;37:573–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw K, Cassel CK, Black C, et al. Shared medical regulation in a time of increasing calls for accountability and transparency: comparison of recertification in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. JAMA 2009;302:2008–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winkler F. Complaints by patients. BMJ 1993;306:472–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker R. Learning from complaints about general practitioners. BMJ 1999;318:1567–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mintzberg H. The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harv Bus Rev 1994:107–14 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.