Abstract

Introduction

High levels of oxidative stress can have considerable impact on the outcomes of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Recent studies have reported that melatonin, a neurohormone secreted from the pineal gland in response to darkness, has significant antioxidative capabilities which may protect against the oxidative stress of infertility treatment on gametes and embryos. Early studies of oral melatonin (3–4 mg/day) in IVF have suggested favourable outcomes. However, most trials were poorly designed and none have addressed the optimum dose of melatonin. We present a proposal for a pilot double-blind randomised placebo-controlled dose–response trial aimed to determine whether oral melatonin supplementation during ovarian stimulation can improve the outcomes of assisted reproductive technology.

Methods and analyses

We will recruit 160 infertile women into one of four groups: placebo (n=40); melatonin 2 mg twice per day (n=40); melatonin 4 mg twice per day (n=40) and melatonin 8 mg twice per day (n=40). The primary outcome will be clinical pregnancy rate. Secondary clinical outcomes include oocyte number/quality, embryo number/quality and fertilisation rate. We will also measure serum melatonin and the oxidative stress marker, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine at baseline and after treatment and levels of these in follicular fluid at egg pick-up. We will investigate follicular blood flow with Doppler ultrasound, patient sleepiness scores and pregnancy complications, comparing outcomes between groups. This protocol has been designed in accordance with the SPIRIT 2013 Guidelines.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from Monash Health HREC (Ref: 13402B), Monash University HREC (Ref: CF14/523-2014000181) and Monash Surgical Private Hospital HREC (Ref: 14107). Data analysis, interpretation and conclusions will be presented at national and international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12613001317785.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This trial is a well-designed pilot study to achieve biochemically and clinically relevant outcomes.

Significant preliminary research has been performed in order to appropriately design the study to fill gaps in current knowledge.

This is the first randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial of melatonin in the field of infertility worldwide and if successful, has the potential to provide a foundation for future large RCTs.

A cross-over design will be used as this is known to improve recruitment rates.

Introduction

Humans are aerobic organisms and when oxygen is utilised in metabolic processes, free oxygen radicals are created as a consequence. These radicals are oxidants and contain ‘free’ valence electrons, making them highly unstable and therefore reactive, capable of causing injury to cells. This occurs by accepting electrons from another molecule (a reductant) in order to reach stability. In doing so, the chemical structure of the reductant is changed, and may no longer be able to perform its designated function. In fact, often the reductant can then produce or sometimes even become an oxidant having the potential to cause oxidative stress in its own right.1 Antioxidative agents are present endogenously and can also be administered exogenously. They are designed to reduce free radicals by donating electrons to stabilise the free radical.2 The term ‘reactive oxygen species’ (ROS) not only includes free radicals but also molecularly stable non-radical molecules which contain oxygen and are capable of causing oxidative stress, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).3 While ROS are necessary for essential physiological processes, an overabundance can result in cellular and tissue damage and this is commonly referred to as ‘oxidative stress’.4 Oxidative stress can be measured in bodily fluids by markers including 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdg).5

Over recent years, the potential role of oxidative stress in the outcomes of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has been gaining increasing attention, in particular with regard to in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). This is perhaps not surprising given that ART exposes both oocytes and embryos to high levels of superoxide-free radicals during gamete and embryo culture.6 In addition to the culture conditions, in vitro the oocytes are not afforded the normal protection of the antioxidant-rich follicular fluid or surrounding cumulus cells, leaving them more susceptible to oxidative damage.7 8 Reproductive processes such as chromosome segregation (resulting in euploid oocytes), polar body extrusion (necessary for haploid oocytes), fertilisation and early cleavage (to avoid arrested embryos) require energy. As the average age of women seeking fertility treatment rises, the level of ROS and subsequent oxidative stress increases, resulting in mitochondrial DNA mutations which in turn affect ATP production in the oocyte. Without the necessary ATP, required cellular processes cannot occur correctly, having a direct effect on the quality of the oocyte, embryo and the final outcome of the IVF procedure.9 10

It has been shown that oocyte quality begins to deteriorate immediately following ovulation. This has been thought to be an inflammatory-driven oxidative stress process11 whereby the production of cytokines and proteases is associated with an increase in ROS which in turn impair oocyte maturation.12–14 Evidence of oxidative damage in in vitro oocytes has been shown to exist as early as 8 h after ovulation.15 Nor surprisingly it has been shown that high levels of the oxidative stress in the follicular fluid of infertile women are associated with poor oocyte maturation and embryo quality, and that inducers of oxidative stress can be used to inhibit oocyte maturation.5 12 Together, these observations highlight the importance of oxidative stress in the developing follicle and in the future success of fertilisation, whether in vivo or in vitro.

Recently, it has been shown that melatonin, a neurohormone secreted from the pineal gland, has important oxygen-scavenging properties which naturally mitigate oxidative stress by both neutralising ROS in human tissues and by inducing endogenous antioxidant enzymes.16–18 Melatonin has been shown to be beneficial as an adjuvant therapy in the management of many medical conditions in which oxidative stress has been implicated, including diabetes, glaucoma, irritable bowel syndrome and fertility.19–22

The effects of melatonin supplementation on culture media,12 21 23–27 gametes,5 15 28 embryos15 29 30 and luteal function31–35 have been identified as useful areas for investigation. Human clinical studies have begun recently, with emphasis on oral supplementation of melatonin during the stimulation cycle and its effects on oocyte and embryo quality.12 36–39

Importantly, melatonin has a remarkably benign safety profile in animal and human studies. A mouse study investigating dose-related effects of melatonin on ovarian grafts found that doses at 200 mg/kg/day have immunosuppressant effects, leading to prolongation of graft survival, however, also resulted in a reduction in healthy follicles. They concluded that doses of greater than 20 mg/kg/day resulted in a reduction in healthy follicles and ovarian size.40 The maternal lowest observed adverse effect level, the lowest level at which an adverse event was observed, appears to be around 200 mg/kg/day, equivalent to over 1 g/day for humans. Furthermore, in rodent studies, no significant adverse effects on either the embryo or fetus have been reported for up to doses of 200 mg/kg/day.41 There have been several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) addressing high doses of melatonin in human adults and children,42–46 and reports have established that toxicity levels in humans are not reached until a daily dose of at least 5 mg/kg.47

Rationale

In the USA, in 2011, only 1 in 4 of all IVF cycles resulted in clinical pregnancy with less than 1 in 5 cycles resulting in live birth.48 That is, 4 out of 5 IVF cycles do not result in a live baby. Clearly there is much room for further improvement, if only to meet societal expectations and reduce healthcare costs. Continued research into novel adjuvant therapies designed to improve IVF outcomes is therefore merited. Several human and animal studies support the use of melatonin in the treatment of infertility, with beneficial actions being largely attributed to its antioxidant properties. Furthermore, melatonin receptors are found on granulosa cells, oocytes and embryos,49 with intrafollicular melatonin concentrations being significantly higher than those found in serum, again suggesting a physiological role in reproduction.39 50 51 The human studies addressing the use of melatonin in infertility treatment undertaken to date have been small and not placebo-controlled. None have attempted to identify an optimal dose.36–38 52 Furthermore, interpretation of any outcomes has been hampered by the within-patient comparison design, where patients act as their own controls.12 39 53

We have designed this study to be the first randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-finding clinical trial to investigate the effect(s), if any, of oral melatonin on the clinical pregnancy rate following IVF/ICSI treatment.

Aims

The overall aim of this trial is to determine whether oral melatonin administration can improve the outcomes of IVF/ICSI. In order to address this, we will determine whether melatonin administration has a dose–response effect in women undergoing IVF/ICSI on:

Biochemical markers of follicle and oocyte health (melatonin, 8-OHdg, progesterone, oestradiol);

Sonographic markers of follicle health;

Patient sleepiness;

Pregnancy rate following IVF/ICSI.

Methods and analyses

This protocol has been designed in accordance with the SPIRIT 2013 Guidelines.54 Recruitment will start in July 2014. This will occur over 2 years. Analysis and dissemination will occur after this period of time. The study is expected to be completed by February 2017.

Study design

Pilot phase II cross-over double-blinded randomised placebo-controlled dose–response trial.

Participants

We plan to recruit a total of 160 infertile women undergoing IVF/ICSI.

Study setting

Patients will be recruited from Monash IVF infertility clinics in Melbourne, Australia over a period of 2 years.

Interventions to be measured

This trial will have four arms. All capsules will be indistinguishable from each other.

Placebo capsule taken twice per day;

2 mg melatonin capsule twice per day (4 mg/day total);

4 mg melatonin capsule twice per day (8 mg/day total);

8 mg melatonin capsule twice per day (16 mg/day total).

Primary outcome

Clinical pregnancy rate,55 defined as the presence of a live pregnancy in the uterine cavity at a transvaginal ultrasound at 6–8 weeks’ gestation.

Secondary outcomes

See table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Clinical secondary outcomes

| Clinical outcomes | Definition |

|---|---|

| Live birth rate | Birth of a live baby after 24 weeks gestation |

| Miscarriage rate | Loss of a diagnosed clinical pregnancy before 20 weeks gestation |

| Sleepiness score | Based on Karolinska56 sleepiness scale during trial medication administration |

| Pregnancy complication and adverse events rates | Including OHSS, multiple pregnancy, congenital or chromosomal abnormalities, stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, delivery before 34 weeks, delivery between 34 and 37 weeks, placenta praevia, gestational diabetes, low birth weight |

| Embryological outcomes | |

| Total number of oocytes collected | |

| Oocyte maturity | |

| Total number of embryos | |

| Embryo quality | |

| Fertilisation rate | The proportion of oocytes that become fertilised |

| Utilisation rate | Proportion of zygotes undergoing embryo transfer or cryopreservation to oocytes fertilised |

| Biochemical outcomes | |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | Presence of serum hCG level of >25 IU/L on day 16 after embryo transfer |

| Melatonin levels in serum | At baseline and prior to oocyte collection |

| Melatonin levels in follicular fluid | Taken from leading follicle from each ovary at time of oocyte collection |

| 8-OHdg levels in serum | At baseline and prior to oocyte collection |

| 8-OHdg levels in follicular fluid | Taken from leading follicle from each ovary at time of oocyte collection |

| Oestradiol and progesterone levels in serum | Taken at baseline, during treatment and at the time of oocyte collection |

| Sonographic outcomes | |

| Follicular blood flow | Measured on last transvaginal ultrasound with power Doppler prior to oocyte collection |

| Uterine artery blood flow | Measured on last transvaginal ultrasound with power Doppler prior to oocyte collection |

hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; 8-OHdg, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine.

Sample size

As this is a pilot dose-finding study, without precedence on which to base accurate power calculations, a power calculation has not been performed. Part of our aim is to provide clarification allowing for larger randomised trials to be designed in the future. We hypothesise that melatonin will have a positive dose–response effect on clinical pregnancy rates after IVF/ICSI. We have chosen a convenience sample of 160 participants, 40 in each of the four groups, in order to assess plausible morphological, biochemical and sonographic surrogate markers for oocyte quality, as well as to provide an indication of the effect size for each dose for our primary outcome, clinical pregnancy rate. Conservatively estimating that, in total, 50% of patients (n=80) do not get pregnant after their first cycle, we may assume that 60 patients will participate in the cross-over arm (allowing for drop-outs) in their second cycle and be allocated to a different treatment group.

Inclusion criteria

Undergoing first cycle of IVF or ICSI;

Age between 18 and 45;

Body mass index between 18 and 35;

Undergoing a gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist cycle (without oral contraceptive pill (OCP) scheduling).

Exclusion criteria

Current untreated pelvic pathology—moderate-to-severe endometriosis, submucosal uterine fibroids/polyps assessed by the treating specialist to affect fertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine malformations, Asherman’s syndrome and hydrosalpinx.

Currently enrolled in another interventional clinical trial.

Concurrent use of other adjuvant therapies (e.g. Chinese herbs, acupuncture).

Current pregnancy.

Malignancy or other contraindication to IVF.

Autoimmune disorders.

Undergoing preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

Hypersensitivity to melatonin or its metabolites.

- Concurrent use of any of the following medications:

- Fluvoxamine (e.g. luvox, movox, voxam);

- Cimetidine (e.g. magicul, tagamet);

- Quinolones and other CYP1A2 inhibitors (ciprofloxacin, avalox);

- Carbamazepine (e.g. tegretol), rifampicin (e.g. rifadin) and other CYP1A2 inducers;

- Zolpidem (e.g. stilnox), zopiclone (e.g. imovane) and other non-benzodiazepine hypnotics.

Inability to comply with trial protocol.

Concomitant care

Aside from trial protocol and inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above, standard concomitant care, such as folic acid supplements, is permitted.

Participant enrolment

This trial will begin recruitment at the level of the infertility specialist. Once identified as requiring IVF/ICSI, and satisfying inclusion and exclusion criteria, the patient will be provided with detailed written information about the trial protocol. After approximately 1 week, the patient will be approached and written informed consent will be obtained by the principle investigator at the first visit with the infertility clinic nurse. Baseline blood tests will be taken and basic demographic information including aetiology of infertility will be recorded. The patient will then be randomised by the principle investigator (see below) to one of the study arms and provided with the trial medication. The participant will start taking the trial medication on the day that ovarian stimulation injections begin (days 2–3 of menses) at 08:00 and 22:00 each day, with the last capsule being taken at 22:00 the night before oocyte collection.

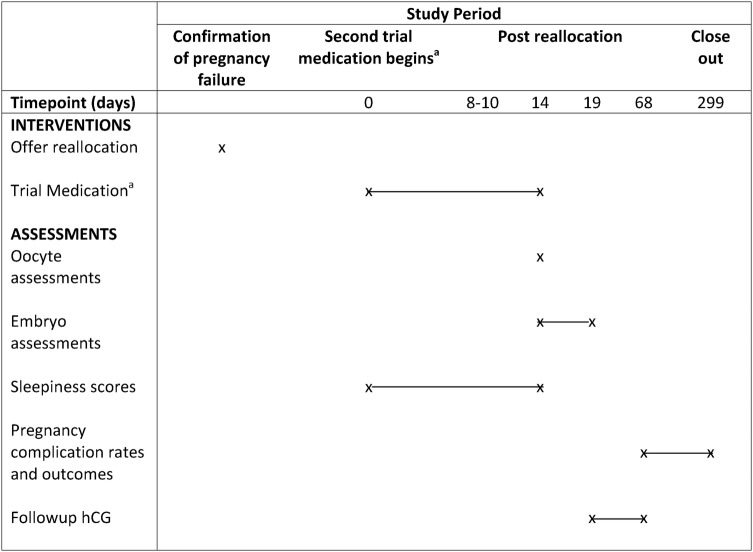

For a summarised participant timeline, see figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Participant timeline schematic—first cycle. aPlacebo, melatonin 2 mg twice daily, melatonin 4 mg twice daily, melatonin 8 mg twice daily. Note: patients who are not pregnant after their first cycle will be offered a second cycle with a different trial medication (figure 2). hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; 8-OHdg, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine.

Figure 2.

Participant timeline schematic—second cycle in those not pregnant after their first cycle. aFor participants who do not become pregnant in their first cycle, each will be offered allocation to the next treatment arm for their second cycle (i.e. A will be allocated to B, B to C, C to D and D to A). ET, embryo transfer; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

Allocation concealment, blinding and randomisation

Association of particular treatment effects (e.g. sleepiness) with certain randomisation codes may become apparent during the trial, and to prevent further allocation bias, proper concealment of treatment allocation is necessary. Each treatment arm will be randomly allocated a letter (A, B, C or D) by way of opaque sealed envelope. Randomisation will be computerised and patients will be randomised at a ratio of 1:1:1:1 to one of the groups, A–D, using the minimisation method, a method of randomisation accounting for factors known to affect the outcome used in small trials to prevent selection bias.57

With a cross-over design, improved patient recruitment is very likely because all non-pregnant participants will be guaranteed at least one cycle with one of the doses of melatonin.58 59 After completing the first study cycle, those participants who are not pregnant will be recruited for the cross-over cycle in which they will be assigned the next treatment arm. For example, if a participant were allocated to treatment group A in their first cycle and did not become pregnant, they would be offered allocation to group B in their second cycle and so on. The half life of melatonin is short, being completely eliminated from the body shortly after 24 h.60 Once patients have had their first stimulated cycle of treatment, a second stimulated cycle will routinely not start until at least 4 weeks after the negative pregnancy test (approximately 6 weeks after last melatonin dose), much longer than the elimination time for melatonin. This will be a sufficient washout period prior to inclusion in a second cycle.

Participants will be blinded by receiving identical-appearing unmarked capsules. All trial researchers will be blinded to treatment allocation group until after analyses are performed at the completion of the trial. A Data Safety Monitoring Committee (see Adverse events and data safety and monitoring section for details) and dispensing pharmacy will be aware of allocation to allow identification of any unbalanced or multiple serious adverse events that may necessitate emergency unblinding of researchers and participants.

Adherence and retention

In order to ensure the integrity of study data, participant adherence to trial protocol will be assessed on a medication administration record updated daily by the participant. At oocyte collection, participants will return medication bottles and compliance will be confirmed by counting remaining tablets. This will be recorded on individual patient compliance forms and patient record forms. Every reasonable effort will be made from the time of enrolment until the end of follow-up to maintain contact with and maintain participant's participation in the trial.

Analysis plan

SPSS V.22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) will be used for data analysis. Primary analysis will occur by the intention-to-treat principle. A secondary analysis will be performed for ‘actual treatment received’. We also intend to perform a separate subanalysis on the data from the first cycle only. Statistical analyses will be performed using χ2 tests for dichotomous categorical outcome variables. Clinical and demographic data will be analysed with parametric tests if they are normally distributed (analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni adjustment), otherwise appropriate non-parametric tests will be implemented (Kruskal-Wallis for between group analyses). Within patient changes (paired data), e.g. when comparing serum levels of melatonin at baseline and after treatment, will be compared using repeated measures ANOVA or Wilcoxon signed-rank test depending on normality of data. A p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant. Where statistically sound, adjusted ORs will be calculated to account for confounders or effect modifiers. To account for missing data, two analyses will be run, with the first excluding missing values and the second by imputation of missing values to determine how conclusions are affected. The SPSS multiple imputation routine (MCMC algorithm known as Fully Conditional Specification) will be used to handle missing data.

Adverse events and data safety and monitoring

An independent Data Safety and Monitoring Committee (DSMC) has been established at Monash Health in order to monitor occurrences of adverse events. The principle investigator will be available by telephone at all times during the trial and participants will be provided with contact details in case of any adverse events. Participants will also be interviewed at the time of their ultrasound and the day of oocyte collection to ascertain the occurrence of any adverse events. Serious adverse events will be recorded separately and followed up until resolution. Such events will be reported to the Monash Health, Monash University, Monash Surgical Private Hospital and Epworth HealthCare Human Research Ethics Committees, the Monash Health DSMC, the Monash Health Therapeutics Committee and, if directed by HREC, to the Australian Therapeutics and Goods Administration.

Trial modification and discontinuation

In the absence of adverse events, the medication regimen will not be modified once started. If other protocol changes are deemed necessary by the investigating team, ethics approval will be sought from all approving Human Research Ethics Committees. Once approved, protocol amendments will be notified to all investigators, administrators (e.g. dispensing pharmacy) and trial participants via telephone.

Patients are permitted to discontinue their inclusion in the trial at any point in time at their request or following an unexpected serious adverse event as described above. The DSMC will perform an interim analysis specifically assessing adverse events after 50% of participants have been recruited. Otherwise, the trial will cease follow-up once patients have given birth from a trial treatment cycle.

Data collection, informed consent forms and confidentiality

Data will be recorded in hardcopy and electronic form. Hardcopies will be stored in a secured filing cabinet at the administering institution. Electronic copies will be stored in encrypted files on a password protected computer. All data will be kept for 15 years; following this time, hardcopies will be destroyed by shredding or burning and electronic copies will be deleted by formatting. Organic samples will be stored until analysis in a secured locked temperature-controlled freezer at the Monash Institute of Medical Research that can only be accessed by authorised staff. Samples and participant records will not contain any directly identifiable information. No additional biological samples will be kept for use in ancillary studies.

For access to data collection forms, including sleep diaries, medication compliance and informed consent forms, please contact the principle investigator.

Ethics and dissemination

Data analysis, interpretation and conclusions will be presented at national and international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. De-identified summary results will also be made publically available on the Monash IVF website.

Discussion

The Melatonin in ART (MIART) trial has the potential to improve IVF treatment protocols, with both immediate and translational benefit to patients. If melatonin is found to improve outcomes after IVF/ICSI, it may become a routine part of management of the infertile couple. We aim to set precedence and a framework by which others may structure further investigation into melatonin and other adjuvant therapies in the future. The intention of this study is as a pilot trial, primarily designed to provide unbiased data as a foundation for further research into this area. It is anticipated that the effect size observed in this trial will be useful to more appropriately power subsequent RCTs with the most effective dose of melatonin. In summary, MIART will be the first trial designed to determine a dose–response relationship of melatonin on biochemical and physiological markers of follicle health and also clinical pregnancy rates.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The idea for the trial was conceived by SF, LR and EW. SF was involved in research design and primary writing of study protocol and manuscript. TO was involved in the design and writing of the manuscript. LR and EW were involved in the trial design, writing, editing and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported both financially and in-kind by the Monash IVF Research and Education Foundation who peer reviewed this study prior to the approval of funding. In-kind and financial support was also afforded by The Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Monash University and The Ritchie Centre, MIMR-PHI.

Competing interests: SF is supported by an NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship. BV and LR are minority shareholders in Monash IVF. LR has received unconditional research and educational grants from MSD and Merck Serono.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval has been obtained from Monash Health HREC (Ref:13402B), Monash University HREC (Ref: CF14/523-2014000181) and Monash Surgical Private Hospital HREC (Ref: 14107).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kojo S. Vitamin C: basic metabolism and its function as an index of oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem 2004;11:1041–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman K. Studies on free radicals, antioxidants, and co-factors. Clin Interv Aging 2007;2:219–36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouayed J, Bohn T. Exogenous antioxidants—double-edged swords in cellular redox state: health beneficial effects at physiologic doses versus deleterious effects at high doses. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2010;3:228–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, et al. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39:44–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamura H, Takasaki A, Taketani T, et al. The role of melatonin as an antioxidant in the follicle. J Ovarian Res 2012;5:5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerin P, El Mouatassim S, Menezo Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7:175–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida M, Ishigati K, Nagai T, et al. Glutathione concentration during maturation and after fertilization in pig oocytes: relevance to the ability of oocytes to form male pronucleus. Biol Reprod 1993;49:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fatehi A, Roelen B, Colenbrander B, et al. Presence of cumulus cells during in vitro fertilization protects the bovine oocyte against oxidative stress and improves first cleavage but does not affect further development. Zygote 2005;13:177–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng H, Ren Z, Yeung W, et al. Low mitochondrial DNA and ATP contents contribute to the absence of birefringent spindle imaged with PolScope in in vitro matured human oocytes. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1681–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Lee J. ATP content of human oocytes and developmental potential and outcome after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 1995;10:415–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espey L. Current status of the hypothesis that mammalian ovulation is comparable to an inflammatory reaction. Biol Reprod 1994;50:233–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura H, Takasaki A, Miwa I, et al. Oxidative stress impairs oocyte quality and melatonin protects oocytes from free radical damage and improves fertilization rate. J Pineal Res 2008;44:280–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura H, Taketani T, Takasaki A, et al. Influence of oxidative stress on oocyte quality and protective role of melatonin as an antioxidant. In: 20th World Congress on Fertility and Sterility, IFFS 2010. vol 7 Munich, Germany: Society for the Study of Reproduction, Inc. Journal fur Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie, 2010:366 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter R, Rosales-Corral S, Manchester L, et al. Peripheral reproductive organ health and melatonin: ready for prime time. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:7231–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lord T, Nixon B, Jones KT, et al. Melatonin prevents postovulatory oocyte aging in the mouse and extends the window for optimal fertilization in vitro. Biol Reprod 2013;88:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood S, Quinn A, Troupe S, et al. Seasonal variation in assisted conception cycles and the influence of photoperiodism on outcome in in vitro fertilization cycles. Hum Fertil 2006;9:223–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2005;3:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivasan V, Spence W, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Melatonin and human reproduction: shedding light on the darkness hormone. Gynecol Endocrinol 2009;25:779–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dholpuria S, Vyas S, Purohit GN, et al. Sonographic monitoring of early follicle growth induced by melatonin implants in camels and the subsequent fertility. J Ultrasound 2012;15:135–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abecia JA, Palacin I, Forcada F, et al. The effect of melatonin treatment on the ovarian response of ewes to the ram effect. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2006;31:52–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Osorio N, Kim I, Wang H, et al. Melatonin increases cleavage rate of porcine preimplantation embryos in vitro. J Pineal Res 2007;43:283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Barcelo EJ, Mediavilla MD, Tan DX, et al. Clinical uses of melatonin: evaluation of human trials. Curr Med Chem 2010;17:2070–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishizuka B, Kuribayashi Y, Murai K, et al. The effect of melatonin on in vitro fertilization and embryo development in mice. J Pineal Res 2000;28:48–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi J, Park S, Lee E, et al. Anti-apoptotic effect of melatonin on preimplantation development of porcine parthenogenetic embryos. Mol Reprod Dev 2008;75:1127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J, Koo O, Kwon D, et al. Effects of melatonin on in vitro maturation of porcine oocyte and expression of melatonin receptor RNA in cumulus and granulosa cells. J Pineal Res 2009;46:22–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei D, Zhang C, Xie J, et al. Supplementation with low concentrations of melatonin improves nuclear maturation of human oocytes in vitro. J Assist Reprod Genet 2013;30:933–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim M, Park E, Kim H, et al. Does supplementation of in-vitro culture medium with melatonin improve IVF outcome in PCOS? Reprod Biomed Online 2013;26:22–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapen M, Zusterzeel P, Peters W, et al. Glutathione and glutathione-related enzymes in reproduction: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;82:171–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eryilmaz O, Devran A, Sarikaya E, et al. Melatonin improves the oocyte and the embryo in IVF patients with sleep disturbances, but does not improve the sleeping problems. J Assist Reprod Genet 2011;28:815–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batıoğlu A, Şahin U, Gürlek B, et al. The efficacy of melatonin administration on oocyte quality. Gynecol Endocrinol 2012;28:91–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taketani T, Tamura H, Takasaki A, et al. Protective role of melatonin in progesterone production by human luteal cells. J Pineal Res 2011;51:207–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0405. Manca ME, Manunta ML, Spezzigu A, et al. Melatonin deprival modifies follicular and corpus luteal growth dynamics in a sheep model. Reproduction 2014;147:885–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baratta M, Tamanini C. Effect of melatonin on the in vitro secretion of progesterone and estradiol 17 beta by ovine granulosa cells. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1992;127:366–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace J, Robinson J, Wigzell S, et al. Effect of melatonin on the peripheral concentrations of LH and progesterone after oestrus, and on conception rate in ewes. J Endocrinol 1988;119:523–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Chai M, Tian X, et al. Effects of melatonin on superovulation and transgenic embryo transplantation in small-tailed han sheep (Ovis aries). Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2013;34:294–301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizzo P, Raffone E, Benedetto V, et al. Effect of the treatment with myo-inositol plus folic acid plus melatonin in comparison with a treatment with myo-inositol plus folic acid on oocyte quality and pregnancy outcome in IVF cycles. A prospective, clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nazzaro A, Salerno A, Marino S, et al. The addiction of melatonin to myo-inositol plus folic acid improve oocyte quality and pregnancy outcome in IVF cycle. A prospective clinical trial. Hum Reprod 2011;26:i227. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pacchiarotti A, Carlomagno G, Unfer V, et al. Role of myo-inositol and melatonin supplementation in follicular fluid of IVF patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. ClinicalTrialsgov 2013; registration number: NCT01540747. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unfer V, Raffone E, Rizzo P, et al. Effect of a supplementation with myo-inositol plus melatonin on oocyte quality in women who failed to conceive in previous in vitro fertilization cycles for poor oocyte quality: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011;27:857–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hemadi M, Shokri S, Pourmatroud E, et al. Follicular dynamic and immunoreactions of the vitrified ovarian graft after host treatment with variable regimens of melatonin. Am J Reprod Immunol 2012;67:401–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jahnke G, Marr M, Myers C, et al. Maternal and developmental toxicity evaluation of melatonin administered orally to pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Sci 1999;50:271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonciarz M, Gonciarz Z, Bielanski W, et al. The effects of long-term melatonin treatment on plasma liver enzymes levels and plasma concentrations of lipids and melatonin in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. J Physiol Pharmacol 2012;63:35–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Lourdes V, Seabra M, Bignotto M, et al. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial, controlled with placebo, of the toxicology of chronic melatonin treatment. J Pineal Res 2000;29:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg-Stern H, Oren H, Peled N, et al. Effect of melatonin on seizure frequency in intractable epilepsy: a pilot study. J Child Neurol 2012;27:1524–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Del Fabbro E, Dev R, Hui D, et al. Effects of melatonin on appetite and other symptoms in patients with advanced cancer and cachexia: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:1271–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voordouw B, Euser R, Verdonk R, et al. Melatonin and melatonin-progestin combinations alter pituitary-ovarian function in women and can inhibit ovulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;74:108–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver D. Reproductive safety of melatonin: a “wonder drug” to wonder about. J Biol Rhythms 1997;12:682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2011 Assisted reproductive technology fertility clinic success rates report. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sampaio R, Conceição S, Miranda M, et al. MT3 melatonin binding site, MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are present in oocyte, but only MT1 is present in bovine blastocyst produced in vitro. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012;10:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-4-865. Brzezinski A, Seibel MM, Lynch HJ, et al. Melatonin in human preovulatory follicular fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987;64:865–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-2-493. Ronnberg L, Kauppila A, Leppaluoto J, et al. Circadian and seasonal variation in human preovulatory follicular fluid melatonin concentration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990;71:492–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciotta L, Stracquadanio M, Pagano I, et al. Effects of myo-inositol supplementation on oocyte's quality in PCOS patients: a double blind trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2011;15:509–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishihara T, Hashimoto S, Ito K, et al. Oral melatonin supplementation improves oocyte and embryo quality in women undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Gynecol Endocrinol 2014;30:359–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan A, Tetzlaff J, Gøtzsche P, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke JF, van Rumste MM, Farquhar CM, et al. Measuring outcomes in fertility trials: can we rely on clinical pregnancy rates? Fertil Steril 2010;94:1647–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reyner L, Horne J. Falling asleep whilst driving: are drivers aware of prior sleepiness? Int J Legal Med 1998;111:120–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altman D, Bland J. Treatment allocation by minimisation. BMJ 2005;330:843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mills E, Chan A, Wu P, et al. Design, analysis, and presentation of crossover trials. Trials 2009;10;27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piantadosi S. Clinical trials: a methodologic perspective. Wiley series in probability and statistics. 2nd edn John Wiley & Sons, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waldhauser F, Waldhauser M, Lieberman H, et al. Bioavailability of oral melatonin in humans. Neuroendocrinology 1984;39:307–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.