Abstract

Objective

This paper describes the processes involved to ensure a diabetes-specific quality of life questionnaire [the “Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life” (ADDQoL)] retained the psychometric properties following cross-cultural adaptation from English to Portuguese.

Methods

One hundred patients were recruited through community pharmacies located in Lisbon through a cross-sectional study design. Patients were asked to respond to the questionnaire on one occasion in time. Data were subjected to factor analysis, and internal consistency and discriminatory power analyses were undertaken.

Results

In the Portuguese sample, 17 items loaded into one factor, with factor loadings above 0.43. The item “worries about the future” loaded weekly into this factor but if removed its internal consistency estimate increased very slightly (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89 to 0.90). A greater negative impact of diabetes on 16 of the 18 quality of life domains was detected for insulin-treated patients, together with a greater negative impact on 14 of the 18 quality of life domains for patients with diabetic complications. The domain “freedom to eat” revealed the greatest negative impact in all patient subgroups, as described in its original version, so the psychometric properties were retained.

Additionally, patients without diabetic complications reported a worse quality of life (greater negative impact) on the first overview item, present quality of life (Z=-2.25; p=0.024); whilst patients on insulin reported a greater negative impact of diabetes on their quality of life (Z=-1.94; p=0.053).

Conclusion

Generally, the Portuguese version for Portugal of the ADDQoL has shown to maintain its original psychometric properties, and could be recommended for use and further evaluation in subsequent studies.

Keywords: Diabetes, Quality of life, Validation studies, Community pharmacy services, Questionnaires, Portugal

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a chronic condition with several implications in daily life of people diagnosed with this disease. Health-care professionals have the duty to monitor diabetic control to ensure prescribed treatment is effective to its full potential. If the optimal therapy is correctly used, patients should achieve a better glycaemic control, which does not necessarily imply there will be an improvement in the patient’s quality of life. Nonetheless, any therapeutic target established should be periodically evaluated to provide guidance on how practitioners can best target their interventions for the benefit of the patient.

Physiological parameters traditionally controlled in diabetic patients include glycaemia, glicated haemoglobin, blood pressure, cholesterol and weight. When evaluating diabetes quality of life, it is most beneficial to use a diabetes-specific tool and, if comparing between different chronic conditions, a generic tool would be preferred.

Since 2001 the implementation of pharmacotherapy follow-up and pharmaceutical care programmes has been taking place in Portuguese community pharmacies.1 Currently these services are provided by many pharmacists nationwide. Demonstrating their added-value to the diabetic population, the Government started reimbursing providers in 2004.2,3 Some criticisms have been made that full implementation has not yet been achieved, and some of the reasons include a lack of multidisciplinary collaboration, particularly with the medical profession.4 In 2005, the Government has asked for an evaluation with clear benefits. Results have been presented in various fora, that show such services contribute to improved glycaemic control after 6 months of pharmacist’s follow-up.5 Whilst the philosophy of pharmaceutical care dates from the sixties, it was not until the nineties that a main objective included contribution to patients’ quality of life6, but quality of life evaluations have not been considered a priority to date, focusing mainly on clinical outcomes and available proxies, including drug-related problems. Future developments will need to include economic and humanistic outcomes so that the evaluation may be considered complete.

The implementation of a patient monitoring programme should be preceded by a thorough review of the available measurement tools. When this care is not taken, programme developers or evaluators may risk using inappropriate measures or developing previously existing ones.

In Portugal, as in most non-English speaking countries, studies evaluating quality of life are still quite scarce. However, in recent years, the growth of instruments available in Portuguese has been exponential. There are currently several studies where well adapted and validated tools for the Portuguese culture have been used, mostly in the areas of anxiety and depression7,8,9,10, but also in respiratory conditions11, amongst others.

The most widely health status measure used in several areas, including diabetes, has been the “short-form 36 (SF-36)”; having been reported as the most frequently used.12 This questionnaire is available in Portuguese, and could in theory be used for evaluating the impact of a diabetes programme; however, this is a health-status measure rather than a quality of life questionnaire and as such the outcomes assessed if used would be very different. Additionally, literature is abundant in criticisms to using unspecific scales in chronic conditions, as it is the case of diabetes.

Alternatively, a diabetes-specific questionnaire that has been validated into Portuguese was searched in literature. A literature search was undertaken using 4 databases (Medline, Embase, IPA and Biopsis Previews) with the keywords “quality of life”, “diabetes” and “Portuguese”, and identified only 3 papers. Repeating the same search in a Portuguese database (B-on Scielo) resulted in 14 hints. Among them, 8 were from Brazil, which were equally inappropriate to use in Portugal for cultural reasons. From the remaining seven papers retrieved, only 5 did not use the word “quality of life” in a theoretical way. Surprisingly, four of these manuscripts used the key-word quality of life but none of the questionnaires in fact measured this concept. The Nottingham Health Profile, as the SF-36 is a health-status measure, the Psychological General Well-being is a measure of well-being, also different from quality of life, and the Coping Responses Inventory explores coping processes developed by patients to deal with their illness which is an even more far apart concept from quality of life; the fifth one, although reporting work with diabetic patients, focused on the evaluation of depression and as such the Beck Depression Inventory was used, a scale which can be used for the overall population if the research focuses on depression. In summary, despite being used in studies with diabetes, to our knowledge, none has been reported as a valid measure for diabetes.

In 2004 a review of the measurement tools available in this area was published, where 13 quality of life questionnaires for use in diabetes were compared.13 This review was published after the ADDQoL’s validation for Portugal, and concluded that only 3 diabetes-specific quality of life questionnaires are suitable for practice research: the ADDQoL, the Appraisal of Diabetes Scale (ADS) and the Diabetes-39 (D-39). The latter has advantages when used in the elderly and in patients with low literacy levels, but also the disadvantage of comprising a considerably high number of items and a visual analogue scale, which can be difficult to read with visual impairments. Additionally, it makes no allowance for the positive impact of diabetes on quality of life, which occasionally can also occur, assuming that all impact must be negative, a pitfall overcome by the “Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life” (ADDQoL). This tool comprised 13 items at the time of publication and was available in Portuguese for Brazil. Currently it comprises 18 items and is also now available for Portugal. This tool has the unique advantage of being individualised, allowing patients to complete only those items that are relevant to them and to rate the importance of the domain being assessed for their quality of life, as well as for the impact of diabetes on the domain. Furthermore, several studies attest the good psychometric properties of the questionnaire. 14,15

A collaborative project was established between “MAPI research Institute”, the author of the original questionnaire and CEFAR, with the purpose of culturally adapting this questionnaire for Portugal. Once finalised, the produced version was to retain similar psychometric properties to the original. This paper describes the work carried out to verify the validity and reliability of the ADDQoL for Portugal, together with future work to validate and refine subsequent versions.

METHODS

A cross-sectional design was used and took place between June and July 2003. The estimated sample size of respondents for robust factor analysis is either 100 or the number of items timed by five , whichever is greater.16 Following this rule of thumb, for an 18-item questionnaire 90 individuals would be needed, in which case 100 were the target sample size.

Patient recruitment was undertaken in community pharmacies where access to ambulatory patients is high. The pharmacies were located in the Lisbon region nearby the research centre conducting the study (CEFAR).

The ADDQoL includes 2 introductory questions and 18 specific items, with the purpose of assessing, according to the patient’s perspective, how much better would his or her life be if they did not have diabetes and how important each of these 18 aspects of life are for the individual.

The scales range from -3 to 3 for quality of life perceptions and from 0 to 3 in attributed importance, both being considered in order to obtain a weighted score (ranging from -9 to 9). Apart from perceived quality of life, data on patients’ demographic characteristics, time since diabetes diagnosis, diabetes type, existing diabetic complications, and prescribed medicines were collected.

Statistical analyses were undertaken in SAS (version 8.2 1999-2001 SAS Institute, Carry NC - USA) and comprised the evaluation of construct validity by means of factor analysis using Varimax rotation and forced 1-factor analysis, and reliability analysis by means of evaluating internal consistency through standardised Cronbach’s alpha estimate. Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the variables and Mann-Whitney’s test for 2 independent samples was used to evaluate discriminatory power, i.e., ability of the questionnaire to detect differences between patients’ subgroups, namely between insulin and non-insulin treated patients and between patients with and without diabetic complications. For all tests, significance levels of 1%, 5% and 10% were used accordingly.

RESULTS

One hundred patients were recruited, 46% being male. Age ranged from 18 to 89 years, with a mean age of 61.3 (SD =12.66) and a median age of 63 years. The mean time since diabetes diagnosis was 12 years and the majority of patients reported having type-2 diabetes (73%). Less than half the patients (45%) mentioned complications from their diabetes. The average number of diabetes specific prescribed drugs was 1.7, ranging from 0 to 4 (SD=0.73), with a median and mode of 2 prescribed drugs. The majority of patients (73%) were prescribed only with oral anti-diabetics (i.e.: no insulin).

According to previous studies using the original ADDQoL, all items should load into one single factor using forced 1-factor analysis.14,15 In the Portuguese sample, 17 items loaded into one factor, with factor loading above 0.43, and only the item “worries about the future” did not load highly into this factor (factor loading=0.24). The internal consistency estimates for the 18 items was Cronbach’s alpha=0.89, considered as very good and close to reported value of the original version.15 Upon removing this item, the internal consistency estimate rose to 0.90. This item’s loading was much lower than 0.4, a cut-off point suggested elsewhere17, but the internal consistency keeping it was still good so the item was kept.

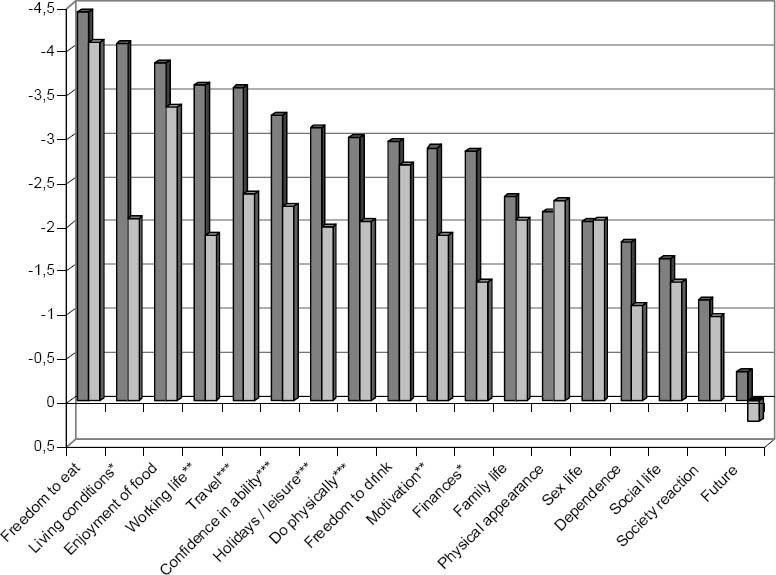

There was a greater negative impact on insulin-treated patients’ quality of life for 16 of the 18 items, and the difference was statistically significant (considering a 10% significance level) for 8 of the items (p<0.1). Similarly, there was a greater negative impact on the quality of life of patients reporting diabetic complications for 14 of the 18 items, only one being significant (p<0.1), less than reported for the UK samples. The impact of each item for these two subgroups is illustrated in table 1 and figure 1.

Table 1.

Impact of diabetes in the quality of life of insulin and non-insulin treated patients and of patients with and without complications

| Item | Insulin treated | Non-insulin treated | p | With complications | Without complications | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I- generic QoL * | 0.407 | 0.306 | 0.569 | 0.159 | 0.463 | 0.024 |

| II- impact of diabetes on QoL* | -1.963 | -1.542 | 0.053 | -1.682 | -1.648 | 0.659 |

| 1- working life | -3.611 | -1.887 | 0.015 | -2.733 | -2.024 | 0.227 |

| 2- family life | -2.333 | -2.059 | 0.801 | -1.927 | -2.340 | 0.335 |

| 3 – social life | -1.615 | -1.348 | 0.985 | -1.585 | -1.321 | 0.983 |

| 4 – sex life | -2.048 | -2.063 | 0.979 | -1.714 | -2.306 | 0.231 |

| 5 – physical appearance | -2.154 | -2.286 | 0.576 | -2.349 | -2.170 | 0.607 |

| 6 – do physically | -3.000 | -2.042 | 0.060 | -2.762 | -1.962 | 0.157 |

| 7 – holidays/ leisure | -3.111 | -1.986 | 0.060 | -2.364 | -2.294 | 0.856 |

| 8 – travel | -3.577 | -2.366 | 0.061 | -3.091 | -2.404 | 0.489 |

| 9 – confidence in ability | -3.259 | -2.214 | 0.096 | -2.953 | -2.189 | 0.092 |

| 10 - motivation | -2.889 | -1.887 | 0.047 | -2.273 | -2.075 | 0.482 |

| 11 – society reaction | -1.148 | -0.958 | 0.627 | -1.047 | -1.000 | 0.493 |

| 12- future | -0.333 | 0.236 | 0.844 | 0.582 | -0.315 | 0.214 |

| 13 – finances | -2.846 | -1.352 | 0.005 | -1.977 | -1.604 | 0.763 |

| 14 – dependence | -1.808 | -1.086 | 0.501 | -1.349 | -1.212 | 0.686 |

| 15 – living conditions | -4.074 | -2.086 | <0.001 | -2.682 | -2.615 | 0.870 |

| 16 – freedom to eat | -4.444 | -4.099 | 0.631 | -4.318 | -4.113 | 0.726 |

| 17 – enjoyment of food | -3.852 | -3.347 | 0.572 | -3.705 | -3.296 | 0.641 |

| 18 – freedom to drink | -2.963 | -2.694 | 0.952 | -2.727 | -2.741 | 0.611 |

Note: columns in light grey represent the items with greater negative impact. Rows in darker grey represent the domain with greater negative impact (freedom to eat), independently of the patient subgroup. * The first two items are rated from 3 to -3 for present quality of life and from -3 to +3 for diabetes-specific quality of life. The other item scores range from -9 to +9 where negative numbers indicate negative impact of diabetes on that aspect of life.

Figure 2.

Diabetes impact on quality of life of patients by treatment subgroup. Sig. *p<0.01, **p<0.05, ***p<0.1

The item “freedom to eat” had the greatest negative impact in all patient subgroups, as described previously.15 There were no differences between treatment subgroups in the overview items, present quality of life and diabetes-specific quality of life.

Patients with diabetic complications reported a worse quality of life (greater negative impact) on the first overview item, present quality of life (Z=-2.25; p=0.024); whilst patients on insulin reported a greater negative impact of diabetes on their quality of life (Z=-1.94; p=0.053).

DISCUSSION

In general, the Portuguese version for Portugal of the ADDQoL held similar psychometric properties to the original version. Nonetheless, some specific psychometric properties need further exploration.

Discriminatory power analyses revealed expected patterns: reduced statistical significance was partially attributable to sample size, which is less than previous studies. Regarding the item “freedom to drink” it is worth mentioning that alcohol consumption in Portugal in 2001 was above the EU-25 average, with a value of 10.5 litres per capita during this year.18 The fact that in the UK this value is around 8.5 litres per capita, may partly explain the different impact of alcoholic habits on diabetes in these two different cultures. In the Portuguese population, such habits are rooted into the country’s wine producing culture, which may influence the weighed impact found (figure 1) of -2.7, markedly negative. This issue should be further tackled by political decision makers.

The highly negative impact of diabetes on ‘living conditions’ in this Portuguese sample of insulin users differs markedly from the lesser impact reported by those not treated with insulin in Portugal or all treatment subgroups in the UK. Indeed this item scored much more negatively in Portugal (-2.7) than in the UK (-1.1) in both treatment subgroups.15 The impact of diabetes on “living conditions” may be associated with support infrastructures in each country’s health-care system. In the UK, institutions exist to provide additional support to diabetic patients in need, whilst in Portugal, the activity of such organisations is mostly centred around health promotion, stimulating self-monitoring, adoption of healthy life styles, and creating multidisciplinary teams to support the patients, but domiciliary care and even economic support available for these patients is still very limited, which may lead to insulin users needing e.g. to live with their parents much longer than they wished. Alternatively, it may be that the wording for this item needs to be refined as these results may indicate the statement is being understood differently from the way originally intended, an issue to further explore on the cognitive debriefing during the development of the ADDQoL-19

The trend to greater negative impact of diabetes on overall quality of life (item II) of insulin treated patients is consistent with previously published data.15

Data showed that the item “worries about the future” had a positive impact on the quality of life of patients with diabetic complications and those with type-2 diabetes. It is possible that the complications were present before diagnosis; a phenomenon commonly known as protopathic bias. One of the limitations of this study was a lack of access to patients’ clinical records, which meant the bias could not be explored by verifying the date of diagnosis and the complete clinical file at that time. It would be important to have this possibility in future studies as it is general knowledge that diabetes is on average diagnosed between 5 to 7 years after its onset in people with type 2 diabetes. The possibility that the translation of ‘worries about the future’ might be less than ideal should be considered. Again, special attention should be paid to the understanding of this item in the cognitive debriefing interviews held during the development of ADDQoL-19.

The fact that the sample was not randomly selected may have had an impact on presented data, patients with complications and other diabetes-related problems are probably overrepresented in this study. The possible effects are on distribution of scores but do not present any problem with the principal component analysis or the internal consistency. For feasibility issues, a convenience sample was considered to be the most realistic approach: CEFAR aims to apply scientific knowledge to practice, in a way that actively involves community pharmacists without negatively impacting their normal functioning. Such an aim sometimes affects the choice of approach. This study is a first-step to validating a tool for use in Portugal. The study has provided useful information for practitioners to include quality of life evaluation in professional practice.

Using a cross-sectional design meant that the evaluation of sensitivity to change or the evaluation of temporal stability through test-retest could not be tested. In future studies these properties could also be explored, using a longitudinal design to evaluate the delivery of pharmaceutical care or pharmacotherapeutic drug-monitoring programmes provided to diabetic patients.

Validating a measurement tool is an ongoing process and requires frequent and successive modifications in the light of up-to-date knowledge. In conclusion, the current version is ready for use, while a new version with 19 items is being developed where the item “worries about the future”, loading weaker in the current study, will be further reviewed. This will be incorporated into future study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors greatly acknowledge the contribution of Prof. Clare Bradley for her advice and constant support and for the essential input into the revision of the manuscript. We also acknowledge Brenda Madureira in pharmacists’ recruitment and in data entry; MAPI Research Institute’s team for the cultural adaptation process; Dr. Madalena Lisboa for the clinical revision of the Portuguese questionnaire, and Dr. Paula Martins in the review of the draft manuscript.

This study was entirely funded by Associação Nacional das Farmácias.

Contributor Information

Filipa Alves Costa, Institute of Health Sciences Egas Moniz (ISCSEM). Centre for Pharmacoepidemologic Research (CEFAR), National Association of Pharmacies (ANF). Lisbon (Portugal)..

José Pedro Guerreiro, Centre for Pharmacoepidemologic Research (CEFAR), National Association of Pharmacies (ANF). Lisbon (Portugal)..

Catherine Duggan, Academic Department of Pharmacy, Barts and The London NHS Trust, London (United Kingdom)..

References

- 1.Costa S, Santos C, Silveira J. Providing Patient Care in Community Pharmacies in Portugal. Ann Pharmacother. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Atendimento a diabéticos evolui para nível superior. Farmácia Portuguesa. 2003;146:24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos MR, Santos R, Costa S, Madeira A, Ferreira AP, Mendes Z, et al. Improving Patient Outcomes and Professional Performance. Achieving Political Recognition. Pharmaceutical Care, beyond the pharmacy perspective. Conference Proceedings. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AS, Hopp T, Sorensen EW, Benrimoj SI, Chen TF, Herborg H, et al. Understanding practice change in community pharmacy: a qualitative research instrument based on organisational theory. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(5):227–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1025880012757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa FA, Ferreira AP, Costa S, Santos R, Horta R, Fontes E, et al. Contributos em Saúde para os Diabéticos. Avaliação do Programa de Cuidados Farmacêuticos: Diabetes. CEFAR, ANF. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Areias ME, Kumar R, Barros H, Figueiredo E. Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(1):30–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coelho AM, Coelho R, Barros H, Rocha-Goncalves F, Reis-Lima MA. Essential arterial hypertension: psychopathology, compliance, and quality of life. Rev Port Cardiol. 1997;16(11):873–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coelho R, Martins A, Barros H. Clinical profiles relating gender and depressive symptoms among adolescents ascertained by the Beck Depression Inventory II. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):222–6. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coelho R, Ramos E, Prata J, Barros H. Psychosocial indexes and cardiovascular risk factors in a community sample. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(5):261–74. doi: 10.1159/000012405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira PL, Mendonça C, Newparth N, Mata P, Juniper EF, Mear I. Quality of life in asthma: cultural adaptation of the Juniper's AQLQ to Portuguese. Qual. Life Res. 1998;7(7):590. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchiors AC, Correr CJ, Rossignoli P, Pontarolo R, Fernandez-Llimos F. Humanistic-outcomes questionnaires in diabetes research and practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(4):354–5. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.4.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melchiors AC, Correr CJ, Rossignoli P, Pontarolo R, Fernandez-Llimos F. Medidas de avaliação da qualidade de vida em diabetes. Parte II: instrumentos específicos. Seguimiento Farmacoterapéutico. 2004;2(2):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley C, Todd C, Gorton T, Symonds E, Martin A, Plowright R. The development of an individualized questionnaire measure of perceived impact of diabetes on quality of life: the ADDQoL. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(1-2):79–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1026485130100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley C, Speight J. Patient perceptions of diabetes and diabetes therapy: assessing quality of life. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(Suppl 3):S64–S69. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kline P. London: Routledge; 1994. An Easy Guide to factor Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todd C, Bradley C. Evaluating the design and development of psychological scales. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of Psychology and Diabetes. Hove: Psychology Press; 1994. pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consumo de álcool na Europa. Eurotrials. 2005;16:2–3. [Google Scholar]