Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to describe the process of translating evidence-based dietary guidelines into a tailored nutrition education program for Korean American immigrants (KAI) with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM).

Methods

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a research process involving researchers and communities to build a collaborative partnership. The study was conducted at a community-based organization. In a total of 79 KAI (intervention, n = 40; control, n = 39) with uncontrolled type 2 DM (A1C ≥7.5%), 44.3% were female and the mean age was 56. 5 ± 7.9 years. A culturally tailored nutrition education was developed by identifying community needs and evaluating research evidence. The efficacy and acceptability of the program was assessed.

Results

In translating dietary guidelines into a culturally relevant nutrition education, culturally tailored dietary recommendations and education instruments were used. While dietary guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) were used to frame nutrition recommendations, additional content was adopted from the Korean Diabetes Association (KDA) guidelines. Culturally relevant intervention materials, such as Korean food models and an individually tailored serving table, were utilized to solidify nutritional concepts as well as to facilitate meal planning. Evaluation of the education revealed significantly increased DM-specific nutrition knowledge in the intervention group. The participants' satisfaction with the education was 9.7 on a 0 to 10-point scale.

Conclusion

The systematic translation approach was useful for producing a culturally tailored nutrition education program for KAI. The program was effective in improving the participants' DM-specific nutrition knowledge and yielded a high level of satisfaction. Future research is warranted to determine the effect of a culturally tailored nutrition education on other clinical outcomes.

Health disparities, especially those involving ethnic minority communities, have become a major part of the national health care agenda. Many researchers have been actively exploring ways to reduce health disparity gaps by providing evidence-based behavioral interventions to underserved ethnic minority populations. The effectiveness of such interventions, however, relies heavily on the quality of cultural adaptation or translation of those interventions, given that most “evidence-based” interventions are developed using effectiveness data from dominant cultural groups.1,2 While there is a growing volume of literature about how to translate English instruments into the language of a target ethnic group and how to validate such an instrument, analogous scientific discussions about the translation of behavioral interventions for certain cultural groups are scarce.

This methodological gap often imposes serious barriers to translating and implementing effective interventions for diabetic patients from ethnic minority communities. For example, nutrition education is an integral part of the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). Adhering to the nutritional guidelines for people with type 2 DM, however, is an extremely difficult task for many individuals.3-6 For many ethnic minority populations in the United States, this task can be twice as challenging because of the lack of culturally relevant dietary guidelines and nutrition education.7,8 Nutritional guidelines developed by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) often do not speak to the unique dietary patterns that ethnic minority groups such as Korean American immigrants (KAI) follow, which can be characterized by a heavy reliance on traditional grains and a vegetable-based diet, combined with an acculturated diet (increased consumption of fat and sweet).9,10 Similarly, nutritional guidelines recommended by the Korean Diabetes Association (KDA) targeting Koreans in Korea do not meet the needs of KAI because of their acculturated dietary pattern and difference in food environment.10,11

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted an intervention development study for KAI with type 2 DM that focused on translating evidenced-based research findings into a culturally relevant educational program for this target group. This article describes the systematic process of translating standard dietary guidelines into a culturally tailored nutrition education program for KAI with type 2 DM. In addition, it illustrates the practical lessons learned from this translational process utilizing the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Research Design and Methods

Design and Setting

In this study, core principles of CBPR were incorporated into the translational process. CBPR is defined as a collaborative process involving researchers and community partners in the research process. The CBPR approach was employed because it is one of the most effective approaches for behavioral interventions focusing on ethnic minority populations.

Sample eligibility criteria for participants in this study were as follows: self-identified KAI, aged 30 years or older, with uncontrolled diabetes (hemoglobin A1C ≥7.5% within the past 6 months), and residing in the Baltimore-Washington area. KAI in the intervention group received two 2-hour nutrition education sessions, 1 week apart, from a bilingual dietician at a local community center, while the control group received the same education. A delayed intervention design that provided the same intervention to the control group after the program was over was used in this randomized controlled pilot trial. Detailed information about the study procedure is provided elsewhere.12

A centrally located community-based organization, The Korean Resource Center, was selected as the educational venue for this study. In this community-based setting, study participants, their family members, community health workers, and diabetes educators were able to actively engage in group education while creating synergy in achieving individual dietary goals.

Procedure

Both formative and summative approaches were used to develop and test a culturally relevant nutrition education program for KAI with type 2 DM. In the formative phase, we first conducted several focus groups composed of bilingual researchers, clinicians, and KAI participants and their family members that were designed to identify perceived barriers to, and strategies for, adopting current dietary guidelines recommended by ADA and KDA. Using input from these focus groups, we then constructed a tailored nutrition education program.

In the summative evaluation phase, the nutrition education program was implemented and tested as part of a self-help intervention program (SHIP) for KAI with type 2 DM (SHIP-DM), in partnership with the Korean Resource Center, a community-based organization. SHIP-DM was tested in a community-based randomized trial of KAI (intervention, n = 40; control, n = 39). Study participants were recruited through advertisements in ethnic newspapers, personal networks, and referrals from local doctors, and randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group by computer-automated random assignment to assure equivalence between groups.

All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins University, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Analysis

The nutrition education was empirically evaluated using the Diabetes Knowledge Test (DKT)13 and a brief satisfaction survey. The DKT consists of 2 parts: 14 general items and 9 insulin-related items. Of the 14 general items, 7 were relevant to nutrition-specific knowledge and thus were used to examine the efficacy of the nutrition education program. For example, the items included the following questions: “Which of the following is highest in carbohydrate?” “Which of the following is a free food? and “What effect does unsweetened fruit juice have on blood glucose?” Nutrition knowledge scores were calculated by totaling the number of items with correct answers, with scores ranging from 0 to 7. Internal reliability coefficient of the 7 items was 0.70 for the sample. Between-group comparisons of the level of nutrition knowledge were made using t tests. The feasibility and acceptability of the translated nutrition education program were assessed using a brief satisfaction survey, which included both Likert-type and open-ended questions. Questions included: “How satisfied are you with the program in terms of (a) content, (b) time, and (c) education facility?” “Overall, how satisfied are you with the educators?” and “Will you recommend the nutrition education program to others?”

Results

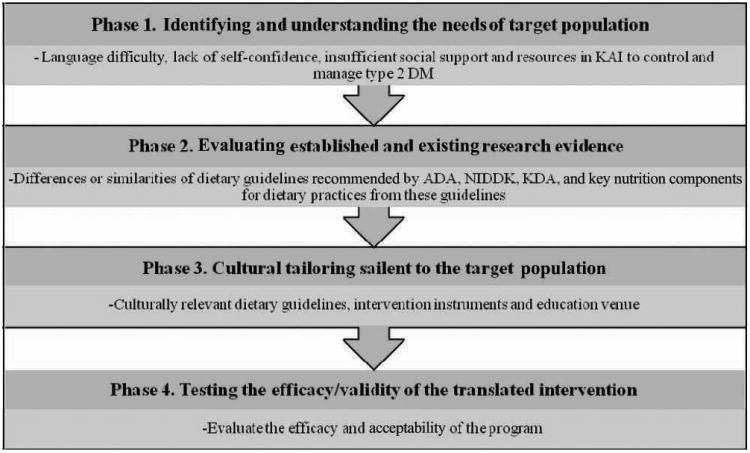

The translational process for the development of a culturally relevant nutrition education program was conducted using the following step-wise approach: identifying the community's needs, evaluating existing research evidence, developing a culturally tailored intervention, and testing the efficacy and validity of the translated intervention (Figure 1). The systematic translational procedure incorporated core principles of CBPR to address the cultural needs of the target population.

Figure 1.

Step-wise approaches to translating established research into culturally tailored practice.

Phase 1: Identifying the Needs of the Target Population

The idea of constructing a nutrition education program for KAI with type 2 DM was first conceived by Korean American health care professionals in 2004. To address the health needs of this culturally and linguistically isolated ethnic immigrant community, the Healthy Korean American Initiative, established through collaboration between academia and the Korean community, was originally established in 1997. Since then, the initiative has planned and conducted a variety of health promotion programs, including health needs assessments, efforts to address attitudes and beliefs about diabetes, and community health worker training for diabetes management.14 A wide array of methods, including focus group meetings, extensive community needs assessment based on previous epidemiological studies, and in-depth interviews with community key informants such as church leaders, community elders, and social organizations, have been used to understand the needs of the target population. Difficulties in managing and controlling type 2 DM and achieving optimal glycemic control, language difficulties, a lack of self-confidence, and insufficient social support and resources have been identified as major barriers experienced by this group.

For this study, a total of 79 study participants were included. Of the 79 participants, 44.3% were female, and the mean age at baseline was 56.4 years (SD = 7.9). A total of 87.3% were married, 70.3% were employed, 53.2% had been in the United States for more than 20 years, and all of the study participants were first-generation migrants whose dietary pattern relied heavily on traditional Korean foods.

Phase 2: Evaluating Existing Evidence

The ADA and NIDDK provide dietary guidelines for patients in the United States, and the KDA's dietary guidelines are targeted to Koreans in Korea. The first step toward translating evidence-based dietary guidelines into a culturally relevant nutrition education for KAI involved examining the existing dietary guidelines established by the ADA, NIDDK, and KDA. A comparison of the similarities and differences in these guidelines was helpful in identifying key aspects that needed to be translated so that an effective and culturally relevant nutrition education program could be developed for our target population. The key differences in these guidelines included the macronutrient distribution, the number of servings of some food groups, and recommendations for fat intake.

Dietary Guidelines of the ADA, NIDDK, and KDA

Macronutrient distribution

Based on treatment goals, the ADA recommends that 60% to 70% of total energy comes from carbohydrates and monounsaturated fat, 15% to 20% from protein, less than 10% from saturated fats, and about 10% from polyunsaturated fat.15 The KDA recommends16 that 60% of total energy comes from carbohydrates, 20% from protein, and 20% from fat. The macronutrient distribution in the KDA guideline is relatively simple and does not include separate recommendations for fat intake according to the type of fat.

Number of servings

Table 1 shows how the number of servings for iso-caloric intake differ among the ADA, NIDDK, and KDA guidelines.

Table 1. Recommended Number of Servings per Day According to Caloric Intake.

| NIDDK | KDAa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| ADA | 1200-1600 kCal | 1600-2000 kCal | 2000-2400 kCal | 1200-1600 kCal | 1600-2000 kCal | 2000-2400 kCal | |

| Carbohydrate | 6-11 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 5-8 | 8-10 | 10-12 |

| Meat (low fat) | 4-6 oz | 4-6 oz | 4-6 oz | 5-7 oz | 1-2 oz | 2 oz | 2-3 oz |

| Medium fat | meat and | meat and | meat and | 3 oz | 3 oz | 3-4 oz | |

| High fat | meat substitutes | meat substitutes | meat substitutes | ||||

| Vegetable | At least 3-5 servings | 3 servings | 4 servings | 4 servings | 7 servings | 7 servings | 7 servings |

| Fruit | 2-4 servings | 2 servings | 3 servings | 4 servings | 1 servings | 1-2 servings | 2 servings |

| Milk | 2-3 servings | 2 servings | 2 servings | 2 servings | 1 servings | 2 servings | 2 servings |

| Fat | Keep servings small | Up to 3 servings | Up to 4 servings | Up to 5 servings | 3 servings | 4 servings | 4-5 servings |

Abbreviations: ADA, American Diabetes Association; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; KDA, Korean Diabetes Association.

The KDA provides detailed number of servings according to caloric intake, in 100-calorie increments from 1200 to 2400 kCal.

Carbohydrates

The ADA guidelines provide a range of servings without specific categorization of caloric intake, while the NIDDK guidelines divide caloric intake into 3 categories and suggests the number of servings for each category. As compared to the ADA and the NIDDK, the KDA provides more detailed information about carbohydrate servings for Koreans. The KDA suggests the number of servings for each level of caloric intake, in 100-calorie increments from 1200 to 2400.

Meat

The ADA and NIDDK guidelines suggest 4 to 7 oz of meat or meat substitutes, while the KDA guidelines subcategorizes meat servings based on fat content and suggest different number of servings for meat with low and medium fat content. Also, the KDA consistently uses the concept of “servings” for meat groups, while the ADA and NIDDK use “ounce,” a more familiar metric unit for Americans.

Vegetables and fruit

The KDA guidelines recommend more servings of vegetables than the NIDDK and ADA guidelines, whereas the recommended fruit servings are higher for the ADA and NIDDK guidelines than for the KDA guidelines.

Milk

The ADA, NIDDK, and KDA guidelines all recommend a similar number of servings for dairy foods, except for individuals at the 1200 to 1600 caloric intake level. At this intake level, the KDA recommends 1 fewer serving.

Fat

The NIDDK and KDA guidelines suggest a similar number of servings of fat, while the ADA guidelines recommend keeping fat intake small, rather than providing a specific number of servings.

Although the ADA and KDA guidelines have similar recommendations for macronutrient distribution, the ADA specifies detailed guidelines for monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat intake. Regarding the number of servings for each level of caloric intake, the ADA and NIDDK guidelines provide relatively simple serving information, while the KDA guidelines provide more detailed food servings for each caloric intake level. Also, the recommended number of servings illustrate how the food sources in the 2 countries differ but still provide the same number of calories. For example, the ADA and NIDDK guidelines recommend more servings from fruits, while the KDA guidelines emphasize more servings from vegetables to address traditional food consumption patterns within similar macronutrient distributions.

Phase 3: Translating Existing Dietary Guidelines Into a Culturally Relevant Nutrition Education Program for KAI With Type 2 DM

In translating existing dietary guidelines into a culturally relevant nutrition education program, we focused on the following: (1) developing a set of culturally relevant and practicable dietary recommendations for KAI with type 2 DM; (2) utilizing culturally acceptable nutrition education instruments; and (3) delivering the nutrition education content in a culturally preferred setting that would influence not only the basic cognitive structure of the group but also our ability to acquire health information.

The nutrition education program was embedded in a 6-week, structured, in-class self-help education program (SHIP-DM) that addressed the following 6 topics: a general overview of type 2 DM, DM medication therapy, DM-related complications and long-term management, nutrition education for DM control (Part I and Part II), and stress management and mental health for individuals with diabetes. These topics were identified as essential for Korean diabetic patients to adequately manage their glucose levels and to master core concepts and skills. As part of the 6 weekly sessions, two 2-hour sessions were devoted to nutrition education (Part I and Part II).

Delivery Methods

The education sessions consisted of both structured lecture and interactive group activities. The nutrition lectures broadly addressed a variety of nutritional topics, including a fundamental food guide pyramid for KAI with type 2 DM, the effect of foods on blood glucose, several meal-planning methods, reading food labels, and healthy food selection and preparation for type 2 DM control, using examples of traditional Korean foods. Interactive group activities were conducted using various formats such as pop quizzes, experience sharing and problem solving as a group. An example of experience sharing and problem-solving involved discussing Koreanspecific food preparation methods to reduce fat and sodium intake and sharing individuals' dietetic treatments. Also, interactive role-play was used to teach nutrition-specific health literacy in the context of DM care, as a means of fostering effective communication. Frequently used nutrition terminology for DM care and control were extensively incorporated into the sessions so that participants could learn to better communicate their dietary regimens with their providers. The education classes were offered in the preferred language (Korean or English) and delivered in a culturally relevant context.

Educational Content

Table 2 summarizes how the educational content was translated from existing dietary guidelines. The content (eg, the recommended number of servings and diabetes food pyramid) was guided by the ADA's dietary guidelines and expanded by incorporating those of the KDA to include culturally familiar nutritional concepts and traditional food examples. For example, the recommended number of servings in each food group for the ADA and NIDDK did not fully reflect the vegetable-based traditional Korean diet. The concept of food exchanges (for example, 3 servings of vegetables are the equivalent of 1 serving of carbohydrate) was particularly emphasized to accommodate the traditional KAI dietary pattern, while also keeping the recommended number of servings. Also, several meal-planning methods were used. For example, a tailored food pyramid was introduced to teach basic nutritional information, while carbohydrate-counting skills were useful in interpreting nutritional information on food labels for the target group.

Table 2. Development of the Education Content of a Culturally Relevant Nutrition Education by Comparing Different Dietary Guidelines.

| Category | ADA/NIDDK | KDA | Examples of Culturally Relevant Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of servings | More servings of fruits and dairy | More servings of vegetables | To reflect the traditional vegetable-centered dietary pattern of KAI, the concept of food exchange was emphasized while maintaining the fundamental frame of the ADA guidelines (ie, 3 vegetable servings = 1 carbohydrate serving) |

| Diabetes food pyramid/food exchange table | Targeted to general US population Consists of a majority of foods frequently consumed by Americans in the United States |

Targeted to Koreans in Korea Consists of traditional Korean foods to address the dietary pattern of Koreans |

Based on the framework of the ADA's diabetes food pyramid (www.diabetes.org), adopting culturally familiar nutritional concepts and traditional Korean food examples from the KDA Considering both acculturated and traditional diets Expanding the food exchange list by including the KDA's food list (http://www.diabetes.or.kr) along with the ADA's food exchange list to consider the acculturated dietary status of KAI |

| Type of meal planning | Carbohydrate counting, plate method, food pyramid | Usually a diabetes food pyramid | Integrating meal-planning methods to introduce basic nutrition information and meet the educational needs of the target population (ie, a culturally tailored food pyramid was used for fundamental nutrition information, while carbohydrate counting skills were taught regarding interpreting nutrition facts on food labels) |

Abbreviations: ADA, American Diabetes Association; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; KDA, Korean Diabetes Association; KAI, Korean American immigrants.

Educational Tools

Individually tailored serving table

An individually tailored food-serving table was adopted from the KDA guidelines to improve individual meal planning skills and delineate dietary goals. Based on gender, height, weight, and activity level, an individual daily caloric intake was calculated for each study participant.16 Based on the individual's daily caloric intake, the recommended number of servings was also calculated to create an individually tailored food serving table. The table provided examples of what 1 serving size in each food category should look like. A printable table, measuring 11 × 9 inches, was given to each participant. Study participants were encouraged to display the table in a prominent place to help them with individual meal planning and preparation.

Daily food diary

To reinforce the effects of nutrition education and to facilitate adherence to their individual dietary goals, the study participants were given a daily food diary and advised to record their daily food consumption, including the types of food they ate, the portion size of each meal, and the meal times and frequency. Each individual's food diary was reviewed by a trained dietician either before or after the nutrition education classes as the basis for a discussion regarding the individual's dietary habits and food consumption pattern.

Culture-specific food model

Utilizing culturally relevant educational tools is a key aspect of educational effectiveness. In this intervention, 78 life-size models of frequently consumed Korean foods were used as a primary teaching tool to visually display what 1 serving size looks like. The model included not only single food items but also combination dishes. Using the food models, study participants were taught to calculate the number of servings in each meal, count servings in various combination Korean dishes, categorize the types of food into the diabetes food pyramid, and practice individual meal planning.

Phase 4: Efficacy and Acceptability of the Nutrition Program

Descriptive statistics yielded a mean nutrition knowledge score of 3.1 (SD = 1.9) in the intervention group at baseline. This score increased to 4.4 (SD = 1.9) at 30 weeks of follow-up. For the control group, the knowledge score was 3.1 (SD = 1.8) at baseline and 3.2 (SD = 1.8) at the follow-up. The between-group difference regarding DM-related nutrition knowledge was statistically significant at follow-up (P = .001). Also, in this pilot study, a total of 35 out of 40 study participants in the intervention group who attended the 6-week in-class DM education sessions completed an exit survey. Of these, 51% responded that the nutrition education was the most satisfactory of the 6 weekly education sessions. All of the study participants said that they would recommend the DM education to other people. In regard to satisfaction in educational contents, time allocation, and education facility, mean satisfaction scores were 2.7, 2.8, and 2.7 out of 3, respectively. In overall satisfaction with the educators, who were professional nurses and dieticians, the average score was 9.7 out of 10, indicating a high level of satisfaction with the program.

Discussion

This article illustrates a translational process using existing standardized dietary guidelines to develop a culturally relevant nutrition education program for an ethnic minority group—a group whose distinct dietary patterns are embedded in their bicultural practice as immigrants and differ from those of their adopted country. The essential concepts for nutrition education in this study, such as the recommended macronutrient distribution and the number of servings for KAI with type 2 DM, were based on the ADA dietary guidelines with additional content adopted from the KDA guidelines to fully address the unique dietary practices of this minority group.

Although this intervention proved to be effective, we encountered several challenges. One of the unique educational challenges for KAI with type 2 DM was to explain the concept of “serving,” a concept unfamiliar in the dietary practice of KAI and Koreans in Korea. To present this unfamiliar nutritional concept, we used the KDA's nutritional content and food examples. Another challenge for KAI was following the recommended dietary guidelines using metric units. The visual food models were effective in addressing this challenge. To incorporate the vegetable-centered Korean diet into the culturally tailored dietary guidelines, a conversion of 1 carbohydrate serving for 3 vegetable servings was suggested.

During the nutrition education presentations, several meal-planning methods, including a culturally tailored diabetes food pyramid, carbohydrate counting, and expanded food exchange list, were introduced. The culturally tailored diabetes food pyramid was effectively used to introduce overall nutritional concepts to diabetic KAI, many of whom have not been exposed to very much health information and nutrition education in the United States.17

In the development of culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minority populations, Resnicow et al18 pointed out 2 dimensions that need to be considered. The first factor is that the “surface structure” involves developing intervention materials and instruments that need to be matched and accepted in the context of the target population's culture and lifestyle, including language or place. The second factor, described as “deep structure,” refers to the cultural, social, and environmental forces that influence the health behavior of the target population. In the present study, surface structure was enhanced not only by using culturally acceptable nutritional concepts and dietary guidelines but also by adopting interventional materials and providing an educational environment that addressed key cultural aspects of the target population. For example, a tangible benefit of using culturally specific food models was to bridge the conceptual discrepancy between theoretical dietary guidelines and daily nutritional practice. Furthermore, visualizing culturally familiar food items empowered participants and maximized the effectiveness of the education. Providing a culturally tailored nutrition education program in the participants' native language was also essential for ethnic minority immigrants, since language barriers, insufficient health literacy, and cultural differences often impede the understanding of essential nutritional information.

The use of linguistically appropriate educational materials in a culturally acceptable setting is often associated with successful intervention implementation.19,20 In regard to appropriate settings for diabetes education, previous studies have supported the belief that group education in community-based settings would be most effective for KAI because of their language and cultural barriers.21 Traditional Korean culture values close familial interdependence and social relationships. Group nutrition education in a community-based setting not only encourages the active involvement of other family members but also encourages synergistic group interaction while building a supportive environment. This strategy enhanced the deep structure of the intervention by supporting the social and environmental forces that influence health behavior, ie, by encouraging family support at home and social support in the community. While most diabetes education is offered in hospital-based clinic settings using one-on-one sessions with a nurse or a dietitian, community-based nutrition education for chronic disease management is a promising approach for ethnic minority populations for the aforementioned reasons.22,23 A community-based venue provides a convenient and informal atmosphere, particularly for groupswho are recent immigrants (such as KAI), who feel stigmatized by having diabetes.22,24

In conclusion, improvements in DM-related nutritional knowledge, together with high satisfaction scores regarding the nutrition education program, indicate the efficacy and acceptability of this program. Based on the study findings, future culturally tailored nutrition education for KAI can be effectively structured by incorporating the following key points:

Provide an interactive, actively engaging education environment using a group approach.

Translate evidence-based, DM-specific dietary guidelines into culturally tailored and standardized dietary guidelines.

Utilize visual educational materials such as traditional food models to reflect the dietary patterns of the target population in a cultural context.

Help to individualize dietary goals for glycemic control and weight management. Deliver education in the preferred language and in a culturally relevant context.

Despite its success, the results of our intervention should be interpreted with some caution. The nutrition education program was very well accepted by the target population, but its efficacy still needs further examination. Although the results of the SHIP-DM partially supported the efficacy of the culturally tailored nutrition education program by producing significantly improved DM-related psychosocial variables and glycemic control in the intervention group,12 further clarification is needed in regard to how much of the improved glycemic control experienced by the study participants was solely attributable to the effect of the culturally tailored nutrition education program. Also, in the future, a community needs assessment and additional formative research should be conducted to explore the intensity and appropriate duration of the nutrition education intervention for KAI.

Despite these potential limitations, the improved health outcomes and reduction in health burden related to type 2 DM that we observed support the efficacy of a standardized and culturally tailored dietary guideline for ethnic minority immigrants. In addition, the translation procedure and education examples used in this study provide support for extending the principles used in this nutrition education program to other ethnic minority populations. As an integral component of DM self-help management skills, nutrition education guided by culturally tailored dietary guidelines is particularly important for ethnic minority immigrants who have limited availability and accessibility to health care systems.25,26 As such, well-designed and culturally tailored nutrition education programs can contribute significantly to improve DM care and management in underrepresented minority populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Deborah McClellan for editorial assistance. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R34 DK071957), LifeScan, Inc (HCC002154), the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR00052), and the National Center for Research Resources/NIH (NCT00505960).

References

- 1.Schafer RG, Bohannon B, Franz M, et al. Translation of the diabetes nutrition recommendations for health care institutions: technical review. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:43–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narayan KM, Gregg EW, Engelgau MM, et al. Translation research for chronic disease: the case of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1794–1798. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin RR, Peyrot M, Saudek CD. Differential effect of diabetes education on self-regulation and life-style behaviors. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:335–338. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haffner SM, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Patterson JK, Stern MP. Increased incidence of type II diabetes mellitus in Mexican Americans. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:102–108. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijan S, Stuart NS, Fitzgerald JT, et al. Barriers to following dietary recommendation in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulponylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wylie-Rosett J. Proceedings from the American Diabetes Association Annual Scientific Sessions. 1989 Jun 6; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samanta A, Campbell JE, Spaulding DL, et al. Eating habits in Asian diabetics. Diabet Med. 1986;3:283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Paik HY, Skinner JD, Spindler AA, Park HR. Nutrient intake of Korean Americans, Korean, and American adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SK, Sobal J, Frongillo EA., Jr Acculturation and dietary practices among Korean Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:1084–1089. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown SA, Hanis CL. A community-based, culturally sensitive education and group-support intervention for Mexican Americans with NIDDM: a pilot study of efficacy. Diabetes Educ. 1995;21:203–210. doi: 10.1177/014572179502100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MT, Han HR, Song H, Lee JE, Kim J, Kim KB. A community-based culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:986–994. doi: 10.1177/0145721709345774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald JT, Funnell MM, Hess GE, et al. The reliability and validity of a brief diabetes knowledge test. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:706–710. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han HR, Kim KB, Kim MT. Evaluation of the training of Korean community health workers for chronic disease management. Health Edu Res. 2007;9:137–146. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:148–198. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korean Diabetes Association. [Accessed September 28 2009]; Web site http://www.diabetes.or.kr.

- 17.Szczepura A. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:141–147. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.026237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, et al. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:477–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawthorne K. Asian diabetics attending a British hospital clinic: a pilot study to evaluate their case. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:243–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JA, Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and attitudes towards prevention among Korean American elders. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1993;8:17–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00973797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown JB, Harris SB, Webster-Bogaert S, Wetmore S, Faulds C, Stewart M. The role of patient, physician, and systematic factors in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract. 2002;19:344–349. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolucci A, Cavaliere D, Scorpiglione N, et al. A comprehensive assessment of the avoidability of long-term complications of diabetes: a case-control study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:927–933. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.9.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonner TD. The group as a basic asset to ethnic minority patients with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:645–655. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, Chin MH, Cagney KA. Cultural leverage: interventions utilizing culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res and Rev. 2007;64:243S–282S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured. Medical Care. 2002;40:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]