Abstract

Intratumoral drug delivery is an inherently appealing approach for concentrating toxic chemotherapies at the site of action. This mode of administration is currently used in a number of clinical treatments such as neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and even standalone therapies when radiation and surgery are not possible. However, even when injected locally, it is difficult to achieve efficient distribution of chemotherapeutics throughout the tumor. This is primarily attributed to the high interstitial pressure which results in gradients that drive fluid away from the tumor center. The stiff extracellular matrix also limits drug penetration throughout the tumor. We have previously shown that neural stem cells can penetrate tumor interstitium, actively migrating even to hypoxic tumor cores. When used to deliver therapeutics, these migratory neural stem cells result in dramatically enhanced tumor coverage relative to conventional delivery approaches. We recently showed that neural stem cells maintain their tumor tropic properties when surface-conjugated to nanoparticles. Here we demonstrate that this hybrid delivery system can be used to improve the efficacy of docetaxel-loaded nanoparticles when administered intratumorally. This was achieved by conjugating drug-loaded nanoparticles to the surface of neural stem cells using a bond that allows the stem cells to efficiently distribute nanoparticles throughout the tumor before releasing the drug for uptake by tumor cells. The modular nature of this system suggests that it could be used to improve the efficacy of many chemotherapy drugs after intratumoral administration.

Keywords: Neural Stem Cells, Nanoparticle Distribution, Nanoparticle Retention, Tumor Tropism

Direct injection of chemotherapeutics into tumors is an obvious approach to reduce systemic toxicities while increasing the active drug concentration at the tumor site. Historically, clinical administration of intratumoral (IT) chemotherapy has been retarded by concerns that it would have minimal impact on distant metastases and that the primary tumor would be more easily removed using surgical resection. However, recent studies have shown that IT therapy can be used to generate an immune response against distant metastases; and that IT therapy prior to surgery can greatly reduce surgical morbidity by shrinking, or in many cases, completely killing the primary tumor.[1] This research has sharply increased interest in IT therapy such that it is now used in a number of clinical scenarios: 1) neoadjuvant treatments that reduce tumor burden prior to radiation and/or surgery; 2) adjuvant treatments that treat positive margin following radiation and/or surgery; and 3) standalone therapies when radiation and surgery are not possible.[2]

Ideally, IT administration would result in even drug distribution throughout the tumor and the drug would be retained long enough to act primarily at the tumor site. Unfortunately, drug distribution in the tumor is often non-uniform and quickly cleared.[3, 4] This is primarily due to poor drug penetration through the stiff tumor extracellular matrix, and poor drug retention in the presence of outward fluid-pressure gradients.[5, 6] Drug retention within the tumor can be improved by encapsulating drugs in particles or hydrogels.[7–10] Unfortunately, loading drugs into macromolecules only exacerbates their poor distribution as these larger constructs have very limited tumor penetration capabilities even when enhanced with pressure-driven flow.[11] Thus, a delivery system is needed that can enhance both retention and distribution of drugs following IT administration.

We have previously shown that HB1.F3 neural stem cells (NSCs) are tumor tropic and selectively migrate to a number of tumor types, including glioma, neuroblastoma, and metastatic breast carcinoma.[12–14] NSCs can penetrate even to hypoxic tumor regions, overcoming high interstitial pressures and stiff extracellular matrices.[15, 16] NSCs have also been modified to distribute therapeutic payloads for tumor killing[17–19]. One therapeutic approach involves an enzyme-prodrug strategy in which the NSCs are genetically engineered to produce the enzyme cytosine deaminase which locally converts the prodrug 5-flurocyosine (5-FC) into the active chemotherapeutic 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)[12]. We recently completed a first-in-human, FDA-approved, clinical trial with this NSC-mediated treatment for recurrent glioma patients.[20] In this approach, the NSCs are injected into the tumor margin after resection and then the prodrug is given systemically, such that the active drug is predominantly generated where the NSCs distribute.

Recently, we demonstrated a complementary payload strategy in which NSCs are surface-engineered with nanoparticles (NPs)[21]. After surface-coupling, the viability and tumor tropism of NSCs was unimpaired even when NPs (drug-free) were 800 nm in diameter[21]. Following IT administration, NSCs significantly enhanced the distribution of surface-conjugated NPs relative to free NPs[21]. NSCs also prolonged NP retention within the tumor[21]. This discovery is part of an emerging body of literature demonstrating that many types of tumor tropic cells can be used to improve NP delivery within tumors, including mesenchymal stem cells,[22] macrophages,[23] and T-cells.[24] For our studies, we continue to work with the HB1.F3 NSC cell line because, in bringing these NSCs to the clinic, they are well-characterized, and found to be chromosomally and functionally stable, non-tumorigenic and minimally immunogenic (HLA Class II negative).[12, 25, 26] Furthermore, NSCs do not have the pro-angiogenic or immunomodulatory properties that can favor tumor growth and are characteristic of mesenchymal stem cells.[27] In addition, for both this initial work and the work reported here, a biotin/avidin-based conjugation strategy was used to attach the NPs to the cell surface. This design was initially selected based on a manuscript describing its successful use to attach microparticles to cells.[28] The use of the biotin/avidin linking strategy was continued in the current report to allow for rapid evaluation of the potential of our NSC-NP strategy to be used for drug delivery. It is likely that for future translational work an alternative linker strategy will have to be developed to avoid potential immunogenicity concerns.[29] It was hypothesized that using larger nanaoparticles (roughly >500 nm) would allow for higher drug loading per NSC as each coupled NP would have increased loading volume. NPs of this size on their own have been safely injected into animals but often have modest tumor targeting properties[30] – a problem addressed by the coupling to the NSCs.

Here we demonstrate that NSC-NP conjugates can be used to improve the efficacy of docetaxel (DTX)-loaded NPs when administered IT in a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) mouse model. TNBC is characterized by tumors that do not express estrogen, progesterone, or HER-2 receptors, and has worse clinical outcome than other breast-cancer subtypes.[31] TNBC was selected as the tumor type for this study in part because it is so difficult to treat and there is an urgent need for new therapies. In addition, we recently characterized the relative tropism of NSCs towards a variety of breast cancer cell lines and found that NSC migration positively correlated with breast cancer invasiveness, such that NSCs were most tropic towards TNBC cell lines.[14] Finally, neoadjuvant chemotherapy for TNBC has been the standard of care for nearly a decade,[31–34] useful both for treating inoperable disease and for reducing the scope of operable surgeries so that mastectomy can be avoided and cosmetic outcomes improved. With current neoadjuvant drug delivery methods, only 22% of women achieve the complete pathological response needed for a promising (94%) 3-year survival prognosis.[35, 36] Others face a less optimistic future, with only 68% surviving past 3 years.[35, 36] Thus, enhancing the efficacy of IT chemotherapy could have a significant overall survival benefit for TNBC patients while also enhancing their quality of life by reducing the scope of surgery.

DTX is a small molecule drug that hyper-stabilizes microtubules leading to mitotic catastrophe and cell death. DTX has shown promise as a neoadjuvant treatment for TNBC, both as a standalone drug[37] and as part of a combination therapy.[38] For the proof of principle work reported here, we chose to work with DTX as a single agent. Very recently, it was shown that NSCs can internalized drug-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles and improve their delivery to brain tumors following local injection.[39] In order to deliver DTX to TNBC using NSC-NP conjugates, we designed a bi-modal drug-release strategy to help ensure that NSC-NP conjugates can be assembled and distribute throughout the tumor before the cyto-toxic drug is released. Prior to working with DTX, which is not fluorescent and thus difficult to track during in vitro experiments, initial experiments were conducted with nile red to simplify monitoring of the system during development. While DTX and nile red are different in many ways, they are both hydrophobic small molecules and thus loading and release data for nile red would be suggestive of how DTX might perform. After using nile red to demonstrate the successful loading of the NPs, the pH-dependent release of cargo, selective surface conjugation of the NPs onto NSCs through a PH-labile bond and the unimpaired behavior of the NSCs, we evaluated the system transporting its intended drug cargo, DTX. In the mildly acidic tumor environment DTX can be delivered both as free drug released from NPs on the surface of the NSCs and also as drug loaded in NPs that are cleaved from the surface and then likely internalized by cancer cells. We found that using this conjugation technique, NSC viability was unaffected after NP coupling, and that the assembled NSC-NP conjugates maintained tumor tropism. Preliminary in vivo results also show that NSC-NP conjugates can improve the efficacy of DTX-loaded NPs in an orthotopic TNBC mouse model.

pH-responsive NP fabrication

NPs composed of poly(ethylene glycol)-poly((diisopropyl amino)ethyl methacrylate (PEG-PDPAEMA) rapidly disassemble when the pH is ≤6.3 in vitro.[40] In order to adapt these particles so that they could be surface-coupled to NSCs, biotin was introduced onto their surface by assembling them from a 1:9 mixture of Biotin-PEG-PDPAEMA: PEG-PDPAEMA (Figure 2a). Following the protocol employed in the original report, the two constituent polymers were synthesized via atom-transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) (Figure 1) from initiators: 1) biotin-PEG-2-bromo-2-methylpropanoate (Supplementary Figure S1) and 2) PEG-2-bromo-2-methylpropanoate (Supplementary Figure S2). It was envisioned that retaining the PEG component of these polymers would be important not only for micelle assembly but also to retard internalization of the NPs following surface conjugation and to minimize the perturbation of the surface properties of the cells – as coupling just PDPAEMA NPs to the surface would introduce islands of cationic density.

Figure 2. pH-responsive NP characterization.

a) Schematic of drug loading and release for biotin-conjugated pH-responsive NPs. b) Scanning electron micrograph demonstrating spherical morphology of biotinylated pH-responsive NPs. Scale bar = 5 μm. c) DLS (black) and fluorometric measurement (red) of NP dissolution and nile red release, respectively, after 4 hour incubations in PBS held at different pHs. d) Representative fluorescent images of nile red-loaded pH-responsive NPs at different pHs. Scale bar = 15 μm and applied to all images in d.

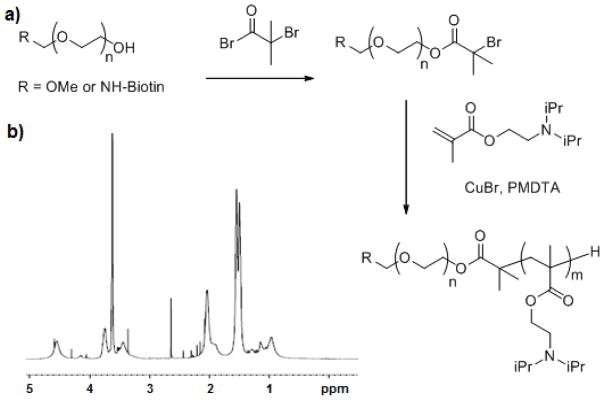

Figure 1. Polymer synthesis for NP fabrication.

a) Schematic demonstrating how a PEG polymer was converted into a macroinitiator by conjugation to α-bromoisobutyryl bromide. Then, the poly((diisopropyl amino)ethyl methacrylate component of the diblock copolymer was synthesized by ATRP. b) 1H NMR spectra of product with characteristic peaks at 0.85, 0.99, 1.55, 2.08, 2.51, 3.39, 3.65, and 4.12.

While PDPAEMA has been used as a component of pH-responsive NPs for delivering siRNA,[41] it was unknown if the biotinylated PEG-PDPAEMA would be effective in releasing a small molecule in a pH-dependent fashion. To assess this, biotinylated NPs were loaded with nile red, a fluorescently active model small (340 Da), hydrophobic drug (Figured 2a). Scanning electron micrographs were used to confirm NPs had the expected spherical morphology (Figure 2b). The pH-responsive release of nile red was investigated in aqueous solutions 4 hours after NP fabrication. Dynamic light scattering was used to monitor NP size as a proxy for disassembly and the relative decrease in 600nm fluorescent emissions were used to quantify nile red release. In agreement with the previous studies, the NPs dissembled and released nile red between pH 6.5 and 6.0 (Figure 2c). To visualize the pH-responsive release, fluorescent images of hydrogel-entrapped NPs were taken after a four hour incubation in aqueous solutions of different pH values. Representative images confirm a sharp reduction in fluorescence intensity below pH 6.5 (Figure 2d).

NSCs retain tumour tropism in vitro following surface conjugation of pH-responsive NPs

Confident that the pH-responsive NPs would retain their cargo at neutral pH and release it below pH 6.5, we proceeded to evaluate coupling the NPs to the surface of the NSCs. This was accomplished using an established protocol to introduce exogenous avidin moieties on the cell surface as depicted in Figure 3a.[28] Briefly, cell surface sialic acid moieties were oxidized to generate aldehyde groups that reacted with biotin hydrazide to form a covalent hydrazone bond. The biotinylated NSCs were then coupled to the biotinylated pH-responsive NPs using an avidin linker. Analysis of NSCs exposed to an excess of avidin demonstrated that the avidinylation process did not impair NSC viability (96 ± 2% live cells)[21], and efficiently introduced avidin onto the surface of the NSCs, as flow cytometric analysis showed that 82 ± 10% of the NSCs contained surface bound avidin (Figure 3b). NP coupling was performed simply by mixing the nile red-loaded, pH-responsive, biotinylated NPs with avidinylated NSCs. After mixing, 99% of NSCs was associated with nile red-loaded NPs as assessed by flow cytometric analysis (Figure 3b). Confocal microscopy was used to visualize NPs after coupling to NSCs (Figure 3c). The majority of NPs were bound to the surface of the NSCs but a significant number of the NPs were also internalized by the NSCs (Supplementary Figure S3). The resulting NSC-NP conjugates showed unaltered tropic efficiencies as compared to unmodified NSC controls when challenged to transmigrate across a porous membrane towards TNBC-conditioned media in Boyden chamber assays (Figure 3d). Flow cytometric analysis showed that 98% of NSC-NP conjugates retained nile-red loaded NPs after migration (Figure 3e, right panel). In contrast, when nile red-loaded, biotinylated, pH-responsive NPs were non-specifically adsorbed onto control NSCs lacking surface avidin functionalization, none of the NPs were retained after migration (Figure 3e, left panel).

Figure 3. NSC biotinylation results in efficient NP coupling.

a) Schematic depicting the biotinylated hydrazone bond incorporated onto the NSC surface that can bind biotinylated NPs when bridged with an avidin linker. b) Flow cytometric analysis of control NSCs (blue) and biotinylated NSCs after incubation with both fluorescein-conjugated avidin (green) and nile-red, biotinylated, pH responsive NPs (red). c) Confocal z-stack projection spanning the thickness of an NSC-NP conjugate stained with calcein-AM where the NPs appear red. Scale bar =10 μm. d) Relative number of transmigrating control NSCs (white), avidinylated NSCs (light gray), or NP-NSC conjugates (dark gray) seeded in the upper well of a transwell chamber after addition of TNBC conditioned media or BSA-containing negative control media into the lower chamber. e) Fluorescence histogram of control NSCs (left) or avidinylated NSCs (right) before (white, dashed) and after (white, dotted) NP coupling. NP retention after transmigration is shaded in gray.

Multiple modes of possible drug release

One design concern was that the pH-responsive NPs only rapidly dissolve and release their cargo below pH 6.5. A pH this low is likely to be rarely be experienced in the extracellular space of a tumor, which more commonly is pH 6.5 – 7.0.[42, 43] We tested two possible solutions to this problem. First, the drug may in fact still get released at pH 6.5 – 7.0 albeit more slowly. Second, the hydrazone bond conjugating the NPs to the NSC surface may also be labile in mildly acidic conditions though it is more commonly used to release drugs within endosomes[44]. If so, the NPs could eventually detach and be available for tumor uptake where the low endosomal pH could trigger rapid drug release (Figure 4a). Results demonstrate that indeed the pH-responsive NPs could release their cargo when incubated at pH 6.5 – 7.0 for 4 weeks (Figure 4b). In addition, flow cytometric analysis was used to demonstrate that the hydrazone bond does cleave in acidic conditions over a period of 1 week, releasing avidin-linked cargo from the NSC surface (Figure 4c). In contrast, when NSCs are cultured at or above pH=7.4, the bond remains intact over this time. However when exposed to pH 7.0, the bond was only stable for 1 day then progressively cleaved over the following 6 days such that only 30% of the initial cargo was still bound to the NSC surface by day 7. Thus, during IT administrations of NSC-NPs, this data suggests that drugs could be delivered both by slow release from the NPs bound to the surface of NSCs and by NPs detaching from the NSCs and being taken up by tumor cells.

Figure 4. Two modes of delayed drug release from NSC-NP conjugates.

a) Schematic depicting two modes of drug release: 1) sustained release from NPs attached to the NSC surface, and 2) burst release from detached NPs that are endocytosed by tumor cells. b) Fluorometric measurement of nile red release after a 28 day incubation in PBS held at different pHs. Loss of fluorescence indicates dye release from the NPs. c) Flow cytometric analysis of the biotinylated hydrazone bond stability as assessed by the relative retention of fluorescein-conjugated avidin on the surface of NSCs cultured for one week in media held at different pHs.

DTX-loaded pH-responsive NPs

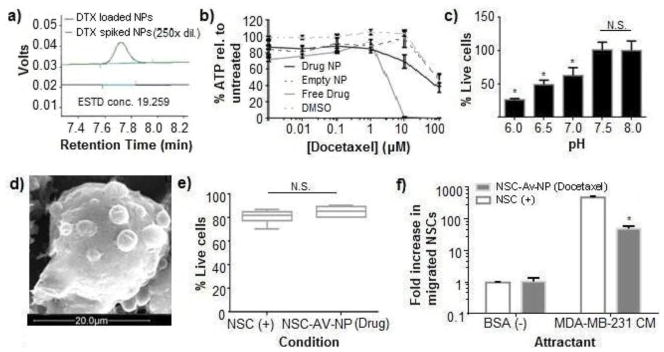

The use of nile red allowed us to readily demonstrate that biotinylated pH-responsive NPs could be prepared, loaded with a hydrophobic small molecule, conjugated to the surface of the NSCs without impairing viability or tumor tropism, and that the small molecule could be released within a mildly acidic environment like that of a tumor. Having thus characterized the NSC-NP interaction using a cytocompatible compound, it was necessary to ensure that similar behavior would be observed when the actual drug DTX was used as the cargo. DTX loading was achieved by including 2.4 wt% DTX in the polymeric component during the emulsion preparation of the NPs. Following isolation of the drug loaded NPs by centrifugation, HPLC analysis of free drug remaining in the supernatant indicated that the loading efficiency was 98% (Figure 5a). This high loading efficiency is consistent with previous studies using similar drug:polymer feed ratios upon NP preparation.[45] The tight binding of DTX by the NPs was further confirmed by comparing the cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells of DTX-loaded pH-responsive NPs at pH 7.4 as compared to equivalent concentrations of free DTX. Equal concentrations of empty NPs were also assessed as negative controls. Results demonstrate that over the 72 hour incubation period, free DTX resulted in a dramatic decrease in cellular ATP content at 10 uM, with an IC50 of ~2 μM, a value consistent with previous reports.[46] In contrast, encapsulation of DTX within the pH-responsive NPs resulted in only minimal reduction in ATP content relative to DMSO or unloaded NP controls (figure 5b). The negligible toxicity of DTX-loaded NPs to MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells was expected given that little DTX was expected to release at pH 7.4 and PEGylated NPs are poorly taken up by cells.[47] To qualitatively evaluate the efficiency of DTX release at different pHs, DTX-loaded NPs were resuspended at an effective [DTX] of 10 μM in media ranging in pH from 6–8 for 12 hours, at which point any remaining NPs were pelleted via centrifugation. The supernatant was applied to established MDA-MB-231 cultures for 72 hours before total ATP content was assessed. In contrast to the initial release at pH 6.5 seen for nile red, DTX was released beginning at pH 7.0 and that release accelerated as the pH was lowered, as indicated by the increasing cell killing as the pH decreased (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. In vitro cytotoxicity of DTX-loaded pH responsive NPs against MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells.

a) HPLC chromatograms of the supernatant collected from DTX-loaded NPs (bottom), and unloaded NPs that were spiked with free DTX after fabrication as a detection standard (top). b) Total ATP content measured in cultures of MDA-MB-231 cells after a 72 hour exposure of either DTX loaded NPs, NPs, free DTX, or DMSO. Cultures were maintained at pH 7.4 for the duration of the experiment. c) In vitro cytotoxicity profile of DTX released from NPs incubated at different pH values against MDA-MB-231 cells as measured using ViaCount flow cytometric analysis. d) SEM micrograph of NP distribution on surface of biotinylated NSC. Scale bar = 20 μm. e) Viability of control NSCs and avidinylated NSCs conjugated to DTX loaded NPs after transmigration assay as assessed using ViaCount FACS analysis. f) Relative number of transmigrating control NSCs (white) and avidinylated NSCs conjugated to DTX-loaded NPs (gray) after being seeded in the upper well of a transwell chamber and migrating to TNBC conditioned media or BSA-containing negative control media present in the lower chamber.

The overall profile of this pH-dependent drug release suggested that there would be some drug leakage in physiological conditions. It was thus essential to verify that the DTX-loaded NPs could be conjugated to the NSCs without killing them or eliminating their tumor tropism. The coupling of DTX-loaded NPs to avidinylated NSCs was performed as described for the nile red-loaded NPs. SEM imaging confirmed that the drug-loaded NPs were attached to the NSC membrane (Figure 5d). Fortunately, surface-conjugation of DTX-loaded pH-responsive NPs to NSCs did not significantly impair cell viability as assessed 12 hours after coupling, with 96 ± 2% of NSCs remaining alive (Figure 5e). This is likely a result of the fact that both only a small amount of DTX is release under these conditions and the NSCs do not divide within this time frame. Interestingly, the NSCs maintained their tropic ability toward MDA-MB-231 conditioned media (Figure 5f), but the migration was reduced relative to untreated NSCs and NSCs conjugated to nile-red loaded NPs. This is consistent with the fact that DTX can interfere with cell motility at concentrations far below that needed to induce cell death.[48, 49] Despite the reduced tumor tropism, the drug carrying NSC-NP conjugates still migrated towards tumor conditioned media nearly 100× more than towards control media, which was sufficient to move forward with preliminary in vivo investigations.

NSCs improve the in vivo efficacy of NPs injected IT

DTX-loaded NPs alone or conjugated to NSCs were administered IT into firefly luciferase (Fluc) expressing MDA-MB-231 tumors. The maximum tolerated dose for free DTX in mice is 20 mg/kg.[50] Here, we selected a DTX dose of 5 mg/kg[51] in effort to demonstrate that the modest therapeutic effect expected using free NPs could be enhanced using NSC-NP conjugates. For the free NP group, DTX loading was quantified by HPLC as described above and a 5 mg/kg DTX dose corresponded to a NP dose of 2.9 × 105 NPs/mouse. For the NSC-NP group, we coupled that same number of NPs with 2.0 × 105 NPs/mouse. At this 1:1.5 coupling ratio, nearly all NPs should be bound to at least one NSC. However, NSC-NPs must be used shortly after preparation so the exact coupling efficiency could not be measured. To ensure equivalent dosing as compared to the free NP group, the NSC-NPs were administered without purification steps to remove unbound NPs.

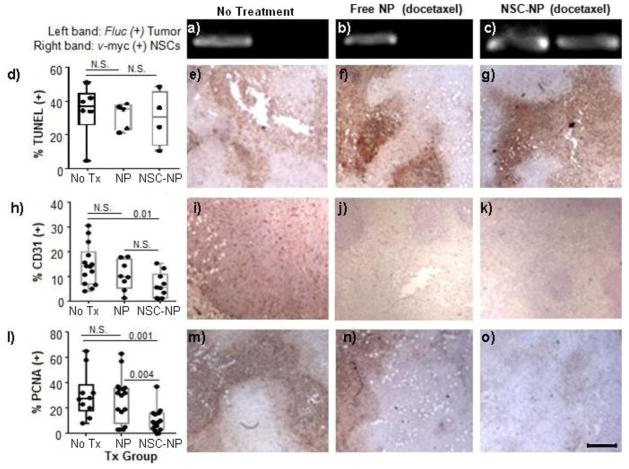

Seven days after treatment, NP–induced cytotoxicity and NSC presence were measured (Figure 6). Because free NPs can be quickly cleared from the tumor (less than 10% remaining after <24 hours)[52], we chose a one-week time point in order to assess if NSCs prolong NP associated tumor-toxicity. NSC presence was evaluated by hemi-nested PCR to confirm the presence of the v-myc gene that is uniquely present in HB1.F3 NSCs (Figure 6a). As expected, v-myc was only detected in the group treated with NSC-NPs, confirming that the NSCs were still present in the tumor 7 days after administration. NP-induced cytotoxicity should reduce tumor microvasculature, cell proliferation and induce apoptosis, so frozen tumor sections were stained for representative biomarkers of these phenomena. Representative pseudo-colored images representing CD31 (tumor microvasculature), PCNA (cell proliferation), and TUNEL (apoptosis) staining in untreated and treated mice are shown (Figure 6b). The results demonstrate that there was only a significant decrease in the area of tumor staining positive for CD31 and PCNA for the NSC-NP group as compared to the saline control, where as the modest therapeutic benefit of free NPs was not statistically significant. These results suggest that NSCs improved the efficacy of IT therapy using DTX-loaded NPs. This could be the product of improved retention and distribution of the DTX throughout the tumor. In contrast, no significant difference in the percentage of TUNEL + cells was observed in any treatment group. There was also no measureable difference in tumor volume or animal weight by day 7. These results suggest that though there was increased activity of NSC-NP conjugates relative to free NPs, the dosing regimen chosen here was insufficient for effective tumor killing. Efficacy results may be further improved in future studies by using higher doses of DTX or by administering weekly rounds (1/week) of treatments at the 5 mg/kg dose used here.

Figure 6. NSC-mediated delivery of DTX-loaded NPs in TNBC bearing mice.

MDA-MB-231.Fluc tumors were grown for two weeks in mice, then administered IT treatments of either saline, free NPs, or NSC-NP conjugates. Seven days after treatment, tumors were harvested and processed for PCR and immunohistochemistry. a–c) PCR for detection of Fluc gene in the TNBC cell line and v-myc gene in NSCs in animals treated with either saline (a), Free NPs (b), or NSC-NP conjugates (c). (Left band): Single-step PCR detection of Fluc gene in MDA-MB-231-luc primary tumor xenografts; (Right panel): Hemi-nested PCR detection of v-myc gene in NSCs injected into the primary tumor. d–o) Tumors were immunohistochemically stained brown for TUNEL (d–g), CD31 (h–k), and PCNA (l–o) then counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). d,h,l) The percentage of positively stained surface area in each treatment group was quantified using ImagePro analysis software to set positive thresholds, psuedocolor, and calculate positive area. Representative brightfield images are shown for TUNEL (e–g), CD31 (i–k), PCNA (m–o) stained tumors in each treatment group. Scale bar = 500μm and applies to all brightfield images in Figure 6.

Conclusions

Here we showed that tumor-tropic NSCs can be utilized to improve the efficacy of pH-responsive NPs loaded with DTX for the IT treatment of a TNBC mouse model. We demonstrated that drug-loaded NPs can be conjugated to NSCs without impairing NSC viability. In addition, the NSCs maintained useful levels of tumor tropism following particle conjugation. When administered IT, NSC-NP conjugates significantly decreased blood vessel density and the percentage of proliferating cells using low doses that rendered freely administered NPs ineffective. This is likely due to improved distribution and retention of the NPs within the tumor microenvironment during the time needed for DTX release from pH-responsive NPs. Intriguingly, model studies with a fluorescent dye indicated two modes of drug release, both directly from the NPs that were still conjugated to NSCs, and an indirect mode wherein the NPs were released from the NSCs and make available for uptake by tumor cells. This indirect mode opens the door to deliver therapeutics like siRNA that require intracellular delivery for activity. Overall, the current work represents a significant proof-of-principle for our long term goal of using tumor tropic NSCs to efficiently deliver chemotherapy throughout tumors. Ideally, future optimization of the coupling chemistry and particle composition will enable both IT and IV therapies[53]. Upon sufficient development, NSC-NP conjugates could be particularly useful for TBNC given its highly invasive, metastatic, and marker-negative status which renders it very difficult to eliminate using traditional therapies.

Materials and Methods

Polymer Synthesis

Synthesis of Biotin-PEG-OH

The biotinylated poly(ethylene) glycol (PEG) polymer was prepared by dissolving 1g of α-hydroxy-x-amine PEG 2000 (JenKem) in 50mM sodium biocarbonate (pH=8.2.) An equimolar amount (0.25 g) of NHS–biotin (Sigma) was then added dropwise and reacted for 2 hours at room temperature. Unreacted NHS-biotin was dialyzed away using 1,000 m.w.c.o. tubing and purified product was lyophilized. Biotinylation was confirmed using 1H NMR in deuterated chloroform with tetramethylsilane (Sigma) used as the internal reference on a Varian 500MHz 1H NMR spectrometer (Supplementary Figure S1a, b). Since the biotin was a terminal modification of the polymer, the biotin makes up 12% of the compound by mass so the splitting patterns of the biotin peaks were hard to visualize but the relevant peaks are assigned here 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.5–4.4 (m, 1H), 4.3 (m, 1H), 3.2–3.1 (m, 1H), 3.0–2.9 (m, 1H), 2.8–2.7 (m, 1H), 2.3–2.1 (m, 2H). The remaining 6 H appear from 1.5 – 1.0 but are confounded by residual grease and solvent.

Synthesis of Biotin-PEG-BR and PEG-BR macroinitiators

Macroinitiators were synthesized as previously described[54]. Briefly, either biotin-PEG-OH or mPEG-OH 2000 (Jenkem) was added to a flask and incubated for 2 hours in an 80 °C oil bath then cooled to room temperature. The polymer was dissolved in dichloromethane (Sigma) and then a 5 molar excess of TEA catalyst was added. The reaction was cooled in an ice bath, then a 5 molar excess of 2-bromoisobutryryl bromide (BIBB) was added in a drop-wise manner. After completing the addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. The resulting solution was concentrated under vacuum, redissolved in tetrahydrafuran (THF) (Sigma), and residual TEA-HBr salts removed by filtration and repeated precipitation into ice cold ether. The resulting mPEG-Br macroinitiator was dried under vacuum for 48 hours then characterized by 1H NMR (Supplementary Figure S2b). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were also recorded on an AVATAR 360 ESP FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet, USA) (Supplementary Figure S2c).

Synthesis of Biotin-PEG-b-DPAEMA and PEG-b-DPAEMA copolymer

Biotin-functionalized and naive PEG-b-DPAEMA copolymers were synthesized by atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) method as previously described[40]. Briefly, the monomer DPAEMA (5mmol) (Polysciences, Co.), N,N,N,N′,N″,N″-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDTA, Sigma) (0.1mmol), and either biotin-PEG-BR or PEG-BR macroinitiators (0.1mmol) were charged into a polymerization tube. Then a mixture of 2-propanol (Sigma) (2 mL) and dimethylformamide (DMF) (Sigma) (2mL) was added to dissolve the monomer and initiator. Oxygen was removed using three cycles of freeze-pump-thaw, then CuBr (0.1 mmol) was added to the reaction tube under nitrogen before sealing the tube in vacuo. The reaction was carried out at 40°C for 8 hours. After polymerization, the reaction mixture was diluted with 10 mL THF and passed through an Al2O3 column to remove the catalyst. The THF solvent was removed via rotoevaporation, and the residue dialyzed in distilled water before lyophilizing to obtain a white powder.

NP Fabrication

The pH-responsive NPs were prepared using a standard water-oil-water emulsion protocol as follows. 10 mg of Biotin-PEG-DPAEMA and 90 mg of PEG-DPAEMA were dissolved in 300 μL of acetone. For loaded particles, 2.4 mg DTX or 0.6 mg Nile Red was also added to the polymer solution. Next, 300 μL of filtered, pH=7.4 PBS was gently added to the surface, and the mixture was sonicated (XL-2000, Misonix Sonicators)on ice for 10 seconds to generate an emulsion. The emulsion was hardened within 6 mL of filtered, pH=7.4 PBS for 4 hours before separating NPs from the free drug contained within the supernatant (see DTX loading content and encapsulation efficiency). Separated NPs were washed 3 times in pH=7.4 1× PBS and collected via centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min.

NP Characterization

Size and Dispersity

Dynamic light scattering (DSL)

Average particle size and distribution measurements (n=5) were performed in PBS at designated pH ranges on a DSL setup equipped with a Brookhaven 90 Plus/BI_MAS digital correlator (Brookhaven Instrum. Corp, NY) at the temperature of 25 °C. The correlation functions were collected at a fixed scattering angle θ = 90° relative to the incident beam. The average hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing objects was calculated from the diffusion coefficient D and the Stokes–Einstein relationship, R = KBT = 6πηD, where KBT is the thermal energy and η is the solvent viscosity.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

NP morphology was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in the secondary electron modes using a FEI Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope. A monolayer of dry NPs was mounted onto an aluminum stab using double-sided carbon tape (TedPella, Inc). The samples were then coated with a 10 nm thick gold film using a sputter coater. Coated samples were examined using an electron acceleration voltage of 30 keV.

DTX loading content and encapsulation efficiency

A theoretical loading mass of 2.4 mg of DTX was loaded into each batch of pH-responsive NPs. To determine the drug loading content, an indirect method was employed as described previously[55]. The unloaded drug was determined by using reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatography (λmax = 230 nm) to measure the free drug found in the supernatant of the prepared drug-loaded NPs. NPs were separated from the supernatant using 3KDa m.w.c.o. spin filters (Millipore). The drug concentration present in the supernatant was assayed on a Shimadzu LC-10AD (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) HPLC system equipped with a Shimadzu UV detector and an Agilent C-18, 5 μm, 200 mm × 4.6 mm RP-HPLC analytical column. The mobile phase consists acetonitrile (spectral grade, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany)/double-distilled water (50/50, v/v) pumped at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The concentration of DTX was determined based on the peak area by reference to a calibration curve that was linear (R2 = 0.99) in the range 100–0.1ng. When DTX alone was spiked into a solution of unloaded NPs, the recovery after spin filtration was 98%. No detectable absorbance was observed when measuring unloaded NPs. The following equations were applied to calculate the drug loading content (DLC) and loading efficiency (LE) as previously described[56].

Release Profile

To monitor the release of hydrophobic small molecule cargo, Nile red was used as an easily quantifiable model drug. 5 mg of NPs were suspended in 1 mL PBS at designated pH values and placed in a water bath at 37 °C. After 4 hours, the sample is spun, the supernatant is withdrawn, and the pellet is resuspended in 300 μL of pH=7.4 1× PBS. This suspension is analyzed in triplicate by a plate reader (λex = 520 nm; λem = 600 nm). This fluorimetric method for Nile red quantification was determined to be linear (R2 = 0.99) in the range 1–700 uM.

Cell culture

All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio), 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator (Thermo Electron Corporation) containing 6% CO2. When cells reached 80% confluency, they were passaged using a 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution (Invitrogen); media was changed every 2–3 days. The Firefly-luciferase (Fluc) expressing TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231.Fluc was obtained from American Type Culture Collection. MDA-MB-231.Fluc cells were used to generate tumor cell-conditioned media by replacing culture media with serum-free media when cells were 80% confluent, followed by a 48 h incubation. Neural stem cell line: The human, v-myc immortalized, HB1.F3 NSC line was obtained from Dr. Seung Kim (University of British Columbia).

In vitro cytotoxicity studies

Intact pH-responsive NPs

Cytotoxicity of DTX-loaded NPs against MDA-MB-231.Fluc cells was assessed using CellTiterGlo ATP assay (Promega) at pH=7.4 over a range of DTX concentrations. Tumor cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 50, 000/cm2 and allowed to adhere for 24 h prior to the assay. Tumor cells were then exposed to either a dose escalation of free DTX, unloaded NPs, or DTX-loaded NPs at 37°C. After 72 h of incubation, media was replaced with 100 μL of cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA], 2 mM EDTA [Bio-Rad], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100 [Fisher Scientific] in diH2O). Manufacturer instructions were followed, and luminescence was measured on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The obtained values are expressed as a percentage of the control cells to which no drugs were added.

Disrupted pH-responsive NPs

Cytotoxicity of DTX released from pH-responsive NPs over a range of different pH values was assessed via flow cytometric analysis after staining with Viacount (GuavaCyte), a proprietary mixture that distinguishes between viable and non-viable cells based on the differential permeability of DNA-binding dyes. The fluorescence of each dye was resolved using a Guava EasyCyte Flow cytometer which outputs the percentage of live and dead cells. Tumor cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 104/cm2 and allowed to adhere for 24 h prior to the assay. In addition, pH-responsive NPs were incubated in media (5 mg NP/mL) at different pH values over night, centrifuged to pellet the NPs, and the supernatant was collected and neutralized to pH=7.4. Tumor cells were then exposed to the neutralized supernatants for 72 hours of incubation. At this time, trypsinized tumor cells were labeled with ViaCount and assessed using flow cytometry.

NSC surface modification

Avidinylation of NSCs

NSCs were avidinylated as described previously[28]. Briefly, cells were grown to 80% confluency, then culture medium was removed and cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before incubation in cold 1 mM NaIO4/PBS solution for 20 min in the dark at 4 °C. NSCs were washed with PBS at pH 6.5 at room temperature (RT). Next, NSCs were incubated in 0.5 mM biotin hydrazide (Sigma) solution in DMEM (Invitrogen) (pH 6.5) for 90 min at RT. Biotinylated NSCs were washed twice with PBS (pH=7.4), before trypsinizing, then incubated in fluorescein-conjugated avidin (10 μg/ml) for 20 min at RT in the dark. Rinsed cells were either characterized via flow cytometry or used for NP coupling.

Flow cytometric characterization

Freshly avidinylated NSCs were cultured for different times (0,1,3,7 days). NSCs were then trypsinized, rinsed, and fixed before 5 × 106 cells/mL were resuspended in staining/wash buffer (SWB) (94% PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+, 5% FBS and 0.001% w/v NaN3 (Sigma)). The retention of bound fluorescein-avidin was detected using flow cytometry. Data is normalized with respect to day 0 and plotted as mean ± SEM (3 experiments; n=10 samples).

NSC-NP coupling

Avidinylated cells were resuspended in a 5 mg/mL NP suspension in PBS (pH 7.4). For coupling, the suspension was incubated (20 min, RT) with periodic trituration. The NSC-NP mixture was then centrifuged at 1200 rpm and any uncoupled NPs remaining in the supernatant were removed. The NSCs were rinsed twice in PBS (12 mL) to encourage removal of loosely bound NPs.

NSC-NP conjugate in vitro viability and tumor tropism assessments (pH=7.4)

Viability

Freshly trypsinized cells were labeled with ViaCount software and analyzed using flow cytometry.

Tumor Tropism

Modified Boyden chamber chemotaxis assays were performed using 24-well cell culture plates with polycarbonate inserts (pore diameter, 8 μm) as described previously[14]. Conditioned media from MDA.MB.231 cells and 5% BSA/DMEM were added to the lower chamber of wells (500 μL/well). Inserts were placed into wells and suspensions of NSCs or NSC-NPs were added to the upper chamber (5×104 cells/250 μL suspended in 5% BSA/DMEM to each well). After incubation (4 h, 37°C), cells that did not migrate were removed from the inner surface of the filter. The membrane tray was then placed in a new lower chamber containing pre-warmed accutase (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 37°C. Detached cells in the buffer were then transferred to a V-bottom 96-well plate and centrifuged (1500 rpm, 5 min). The buffer was aspirated, and cells were labeled with Viacount and counted using flow cytometry. Plot showing mean ± SEM is shown (3 experiments; n=12 samples).

Imaging NSC-NP conjugates in vitro

Confocal Microscopy

A suspensions of NSC-NP conjugates (1×107 cells/mL) was labeled with Calcein-AM (Invitrogen) for 15 min, then encapsulated within 1% low melting-point agarose (Sigma) to stabilize the cells for imaging. Then 200 μL of the agarose suspension was placed on a glass slide and a coverslip was used to create a thin gel layer that polymerized upon exposure to 4°C for 10 min. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a 100x oil immersion objective. The representative image shown represents a z-stack compiled from 1 μm optical slices spanning the entire thickness of the NSC-NP conjugate.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

NP surface localization was verified with SEM after spin-coating NP-coupled NSCs on glass coverslips (CytoSpin) and then fixing cells with 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Samples were then sputter coated with gold and imaged.

Stability of NSC-associated NPs in vitro

Unmodified and avidinylated NSCs were exposed to 5 mg/mL nile-red loaded, biotinylated, pH-responsive NPs. After washing twice, NSC-NP conjugates were resuspended in PBS or challenged to migrate through a boyden chamber membrane. The increase in red fluorescence as a result of initial and retained particle binding was quantified using flow cytometry and analyzed using FlowJo Software (2 experiments; n=8 samples).

In vivo orthotopic TNBC model

NOD-SCID mice (Charles River) that were 7–8 weeks old were anesthetized with isofluorane before inoculation with 2 million MDA-MD-231.Fluc human TNBC cells into the 4th mammary fat pad. After 14 days, caliper measurements showed the tumor had reached a volume of about 20 mm3 and positive xenogen signal confirmed presence of a viable tumor. Tumor volume was calculated as L2*W, where L is the smaller dimension. At this time, mice were randomized and received IT injections of 5 mg/kg DTX delivered either as free-NPs (2.9×105 NPs) or NSC-NPs (2×105 NSCs, 2.9×105 NPs). Control animals received saline injections. Each group was comprised of 3 mice. Over the next week, tumor sizes were measured by a caliper, and body weight was monitored. All animal protocols were approved by the City of Hope Institutional Animal care and Use Committee. Mice were euthanized consistent with the recommendations of the Panel of Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association when they appeared to be in discomfort or distress as judged by independent animal care personnel. Mice were housed in an AAALAC-accredited facility and were given food and water ad libitum.

Treatment efficacy determination

Tissue harvesting and processing

Mice were euthanized 7 days post treatment by CO2 asphyxiation and the harvested tumor was further fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h before sinking in 30% sucrose for 48 h. The tissues were frozen in TissueTek OCT (Sakura inetek Europe B.V.) and sectioned (10 μm thick) using a cryostat (Leica 17–20). Sections were collected on slides, rinsed, and incubated in blocking solution (5% BSA, 3% normal horse serum, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h. Apoptosis was assessed on tumor sections using manufacturer’s recommended TUNEL protocol (Calbiochem). Other sections were incubated with primary antibodies (24 hours, 4°C) for PCNA (1:100) (Chemicon) and CD31 (1:50) (BD pharmingen), followed by an incubation (4 hours, room temp) with biotinylated goat anti-rat and anti-mouse IgGs respectively (1:400) (Vector Laboratories) which was then amplified using Vectastain ABC Elite (Vector Laboratories) and developed upon exposure to DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories). Stained sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin and sealed with CytoSeal Hard Set mounting medium before brightfield imaging.

Digital Analysis of Tissue Sections

Images of 4 sections/tumor taken a even tumor depths were obtained using equivalent exposure at 1x magnification on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope equipped with a SPOT RT Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Images were recorded and stored using SPOT Advanced and Adobe Photoshop software. To automatically calculate the percent of each section that stained positive for different antibodies, Image-Pro Plus 3.0 software (Media Cybernetics; Silver Spring, MD) was used as previously described.[57] Briefly, images were pre-processed to enhance DAB immunostaining by brightening (level=50) and flattening the image. The tumor section was then outlined and positive signal within the section defined using the following parameters which excluded larger artifacts: area (1–10,000 pxl), aspect (1–10), per area (0–1). The histogram based mode of color threshholding was used to convert pre-processed images from RGB to the HIS (Hue–Saturation–Intensity) color mode and three parameters were manually gated: Hue-250, Sat-250, Inten-170. Finally, the “count” command was used to calculate the percentage of positive stained tumor area.

PCR

Genomic DNA from tumor sections was purified using DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). Nested PCR was used to detect v-myc using 400 nM of the following primers: first-round (fwd: 5′-CCTTTGTTGATTTCGCCAAT-3′; rev: 5′-GCGAGCTTCTCCGACACCACC-3′); second-round (fwd: 5′-TCACAGCCAGATATCCAGCAGCTT-3′; rev: 5′-AGTTCTCCTCCTCCTCCTCG-3′). The size of the v-myc amplicon in second-round PCR was 198 bp. Positive-control reactions consisted of genomic DNA from HB1.F3.CD NSCs while negative controls contained genomic DNA from naïve mouse tissue. Single step PCR was used to detect Fluc using 400 nM of the following primers: fwd: 5′-TTGCCTTCACTGATGC TCAC-3′; rev: 5′-CCAATGAACAGGGCTCCTAA-3′. The size of the Fluc amplicon was 178 bp. All PCR reactions involved 40 cycles with 250 ng DNA template and Platinum PCR supermix high fidelity (Invitrogen).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed students t-test (* p <0.05).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Tim Synold for assistance with HPLC; Dr. Zhuo Li, Ricardo Zerda, and Dr. Marcia Miller for technical assistance with scanning electron microscopy (SEM funding was provided by DOD 1435-04-03GT-73134); Dr. Brian Armstrong for assistance with confocal microscopy experiments; STOP Cancer; The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation; Mary Kay Foundation; California Institute of Regenerative Medicine; the Alvarez Family Foundation; and the Accelerated Brain Cancer Cures Foundation for their generous financial support. RM was supported by a fellowship from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (grant number TG2-01150) and the Ladies Auxiliary of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CIRM or any other agency of the State of California. Research reported in this publication included work performed in the Electron Microscopy, Light Microscopy Digital Imaging and Analytical Pharmacology Cores supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary figures describing biotin-PEG-OH (Supplementary Figure S1) and macroinitiator (Supplementary Figure S2) characterization are provided.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldberg EP, Hadba AR, Almond BA, Marotta JS. Intratumoral cancer chemotherapy and immunotherapy: opportunities for nonsystemic preoperative drug delivery. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2002;54:159–180. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Good LM, Miller MD, High WA. Intralesional agents in the management of cutaneous malignancy: a review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mairs RJ, Wideman CL, Angerson WJ, Whateley TL, Reza MS, Reeves JR, Robertson LM, Neshasteh-Riz A, Rampling R, Owens J, Allan D, Graham DI. Comparison of different methods of intracerebral administration of radioiododeoxyuridine for glioma therapy using a rat model. British journal of cancer. 2000;82:74–80. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roelcke U, Hausmann O, Merlo A, Missimer J, Maguire RP, Freitag P, Radu EW, Weinreich R, Gratzl O, Leenders KL. PET imaging drug distribution after intratumoral injection: the case for (124)I-iododeoxyuridine in malignant gliomas. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43:1444–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2006;6:583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heldin CH, Rubin K, Pietras K, Ostman A. High interstitial fluid pressure - an obstacle in cancer therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2004;4:806–813. doi: 10.1038/nrc1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orenberg EK, Miller BH, Greenway HT, Koperski JA, Lowe N, Rosen T, Brown DM, Inui M, Korey AG, Luck EE. The effect of intralesional 5-fluorouracil therapeutic implant (MPI 5003) for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992;27:723–728. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70245-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almond BA, Hadba AR, Freeman ST, Cuevas BJ, York AM, Detrisac CJ, Goldberg EP. Efficacy of mitoxantrone-loaded albumin microspheres for intratumoral chemotherapy of breast cancer. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2003;91:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinehart JM, Sperling M, Phillips S, Kraus S, Gordon S, McCarty JM, Webster GF, Skinner R, Korey A, Orenberg EK. Intralesional fluorouracil/epinephrine injectable gel for treatment of condylomata acuminata. A phase 3 clinical study. Archives of dermatology. 1997;133:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller BH, Shavin JS, Cognetta A, Taylor RJ, Salasche S, Korey A, Orenberg EK. Nonsurgical treatment of basal cell carcinomas with intralesional 5-fluorouracil/epinephrine injectable gel. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997;36:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holback H, Yeo Y. Intratumoral drug delivery with nanoparticulate carriers. Pharmaceutical research. 2011;28:1819–1830. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Metz MZ, D’Apuzzo M, Gutova M, Annala AJ, Synold TW, Couture LA, Blanchard S, Moats RA, Garcia E, Aramburo S, Valenzuela VV, Frank RT, Barish ME, Brown CE, Kim SU, Badie B, Portnow J. Neural Stem Cell–Mediated Enzyme/Prodrug Therapy for Glioma: Preclinical Studies. Science translational medicine. 2013;5:184ra159. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Danks MK. Stem and progenitor cell-mediated tumor selective gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2008;15:739–752. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao D, Najbauer J, Annala AJ, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Gutova M, Polewski MD, Gilchrist M, Glackin CA, Kim SU, Aboody KS. Human neural stem cell tropism to metastatic breast cancer. Stem Cells. 2012;30:314–325. doi: 10.1002/stem.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao DH, Najbauer J, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Gutova M, Glackin CA, Kim SU, Aboody KS. Neural Stem Cell Tropism to Glioma: Critical Role of Tumor Hypoxia. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1819–1829. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu SX, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Snyder EY. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: Evidence from intracranial gliomas (vol 97, pg 12846, 2000) P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:777–777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auffinger B, Ahmed AU, Lesniak MS. Oncolytic virotherapy for malignant glioma: translating laboratory insights into clinical practice. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:32. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnarr K, Mooney R, Weng Y, Zhao D, Garcia E, Armstrong B, Annala AJ, Kim SU, Aboody KS, Berlin JM. Gold Nanoparticle-Loaded Neural Stem Cells for Photothermal Ablation of Cancer. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2013;2:976–982. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank RT, Edmiston M, Kendall SE, Najbauer J, Cheung CW, Kassa T, Metz MZ, Kim SU, Glackin CA, Wu AM, Yazaki PJ, Aboody KS. Neural stem cells as a novel platform for tumor-specific delivery of therapeutic antibodies. PloS one. 2009;4:e8314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aboody K, Capela A, Niazi N, Jeffrey Stern H, Temple S. Translating Stem Cell Studies to the Clinic for CNS Repair: Current State of the Art and the Need for a Rosetta Stone. Neuron. 2011;70:597–613. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rachael Mooney YW, Tirughana-Sambandan Revethiswari, Garcia Elizabeth, Hernandez Valerie, Aramburo Soraya, Annala Alexander, Berlin Jacob, Aboody Karen. Human Neural Stem Cell-Mediated Targeting of Nanoparticles to Brain Tumors. Future Oncology. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.217. Accepted (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Guan Y, Liu H, Hao N, Liu T, Meng X, Fu C, Li Y, Qu Q, Zhang Y, Ji S, Chen L, Chen D, Tang F. Silica nanorattle-doxorubicin-anchored mesenchymal stem cells for tumor-tropic therapy. ACS nano. 2011;5:7462–7470. doi: 10.1021/nn202399w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madsen SJ, Baek SK, Makkouk AR, Krasieva T, Hirschberg H. Macrophages as cell-based delivery systems for nanoshells in photothermal therapy. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2012;40:507–515. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0415-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephan MT, Stephan SB, Bak P, Chen J, Irvine DJ. Synapse-directed delivery of immunomodulators using T-cell-conjugated nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5776–5787. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SU. Human neural stem cells genetically modified for brain repair in neurological disorders. Neuropathology. 2004;24:159–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SU, Nakagawa E, Hatori K, Nagai A, Lee MA, Bang JH. Production of immortalized human neural crest stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;198:55–65. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-186-8:055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljujic B, Milovanovic M, Volarevic V, Murray B, Bugarski D, Przyborski S, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML, Stojkovic M. Human mesenchymal stem cells creating an immunosuppressive environment and promote breast cancer in mice. Sci Rep. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/srep02298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamachari Y, Pearce ME, Salem AK. Self-Assembly of Cell–Microparticle Hybrids. Advanced materials. 2008;20:989–993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paganelli G, Magnani P, Zito F, Villa E, Sudati F, Lopalco L, Rossetti C, Malcovati M, Chiolerio F, Seccamani E, et al. Three-step monoclonal antibody tumor targeting in carcinoembryonic antigen-positive patients. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5960–5966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohane DS. Microparticles and nanoparticles for drug delivery. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2007;96:203–209. doi: 10.1002/bit.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Minckwitz G, Martin M. Neoadjuvant treatments for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2012;23(Suppl 6):vi35–39. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estevez LG, Gradishar WJ. Evidence-based use of neoadjuvant taxane in operable and inoperable breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:3249–3261. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann M, von Minckwitz G, Smith R, Valero V, Gianni L, Eiermann W, Howell A, Costa SD, Beuzeboc P, Untch M, Blohmer J-U, Sinn H-P, Sittek R, Souchon R, Tulusan AH, Volm T, Senn H-J. International Expert Panel on the Use of Primary (Preoperative) Systemic Treatment of Operable Breast Cancer: Review and Recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2600–2608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, Andre F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:1275–1281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amat S, Bougnoux P, Penault-Llorca F, Fetissof F, Cure H, Kwiatkowski F, Achard JL, Body G, Dauplat J, Chollet P. Neoadjuvant docetaxel for operable breast cancer induces a high pathological response and breast-conservation rate. British journal of cancer. 2003;88:1339–1345. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutcheon AW, Heys SD, Sarkar TK, Aberdeen Breast G. Neoadjuvant docetaxel in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2003;79(Suppl 1):S19–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1024333725148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng Y, Morshed R, Cheng SH, Tobias A, Auffinger B, Wainwright DA, Zhang L, Yunis C, Han Y, Chen CT, Lo LW, Aboody KS, Ahmed AU, Lesniak MS. Nanoparticle-Programmed Self-Destructive Neural Stem Cells for Glioblastoma Targeting and Therapy. Small. 2013 doi: 10.1002/smll.201301111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou K, Wang Y, Huang X, Luby-Phelps K, Sumer BD, Gao J. Tunable, Ultrasensitive pH-Responsive Nanoparticles Targeting Specific Endocytic Organelles in Living Cells. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2011;50:6109–6114. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu H, Zou Y, Wang Y, Huang X, Huang G, Sumer BD, Boothman DA, Gao J. Overcoming endosomal barrier by amphotericin B-loaded dual pH-responsive PDMA-b-PDPA micelleplexes for siRNA delivery. ACS nano. 2011;5:9246–9255. doi: 10.1021/nn203503h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular pH gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Lin Y, Gillies RJ. Tumor pH and its measurement. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51:1167–1170. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patil R, Portilla-Arias J, Ding H, Konda B, Rekechenetskiy A, Inoue S, Black KL, Holler E, Ljubimova JY. Cellular Delivery of Doxorubicin via pH-Controlled Hydrazone Linkage Using Multifunctional Nano Vehicle Based on Poly(beta-L-Malic Acid) International journal of molecular sciences. 2012;13:11681–11693. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng D, Li X, Xu H, Lu X, Hu Y, Fan W. Study on docetaxel-loaded nanoparticles with high antitumor efficacy against malignant melanoma. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2009;41:578–587. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferlini C, Scambia G, Distefano M, Filippini P, Isola G, Riva A, Bombardelli E, Fattorossi A, Benedetti Panici P, Mancuso S. Synergistic antiproliferative activity of tamoxifen and docetaxel on three oestrogen receptor-negative cancer cell lines is mediated by the induction of apoptosis. British journal of cancer. 1997;75:884–891. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suresh AK, Weng Y, Li Z, Zerda R, Van Haute D, Williams JC, Berlin JM. Matrix metalloproteinase-triggered denuding of engineered gold nanoparticles for selective cell uptake. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2013;1:2341–2349. doi: 10.1039/c3tb00435j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bijman MNA, van Berkel MPA, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Boven E. Interference with actin dynamics is superior to disturbance of microtubule function in the inhibition of human ovarian cancer cell motility. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;76:707–716. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murtagh J, Lu H, Schwartz EL. Taxotere-Induced Inhibition of Human Endothelial Cell Migration Is a Result of Heat Shock Protein 90 Degradation. Cancer Research. 2006;66:8192–8199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ernsting MJ, Foltz WD, Undzys E, Tagami T, Li S-D. Tumor-targeted drug delivery using MR-contrasted docetaxel – Carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3931–3941. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Undzys E, Holwell N, Foltz WD, Li SD. Docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles that target alpha-smooth muscle actin-expressing stromal cells suppress breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4862–4871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacKay JA, Deen DF, Szoka FC., Jr Distribution in brain of liposomes after convection enhanced delivery; modulation by particle charge, particle diameter, and presence of steric coating. Brain Research. 2005;1035:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown AB, Yang W, Schmidt NO, Carroll R, Leishear KK, Rainov NG, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Aboody KS. Intravascular delivery of neural stem cell lines to target intracranial and extracranial tumors of neural and non-neural origin. Hum Gene Ther. 2003 Dec 10;14(18):1777–85. doi: 10.1089/104303403322611782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dayananda K, Kim M, Kim B, Lee D. Synthesis and characterization of MPEG-b-PDPA amphiphilic block copolymer via atom transfer radical polymerization and its pH-dependent micellar behavior. Macromol Res. 2007;15:385–391. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sebak S, Mirzaei M, Malhotra M, Kulamarva A, Prakash S. Human serum albumin nanoparticles as an efficient noscapine drug delivery system for potential use in breast cancer: preparation and in vitro analysis. International journal of nanomedicine. 2010;5:525–532. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s10443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park J, Fong PM, Lu J, Russell KS, Booth CJ, Saltzman WM, Fahmy TM. PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles for the improved delivery of doxorubicin. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2009;5:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johansson AC, Visse E, Widegren B, Sjogren HO, Siesjo P. Computerized image analysis as a tool to quantify infiltrating leukocytes: a comparison between high- and low-magnification images. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2001;49:1073–1079. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.