Abstract

The purpose of this study was to characterize the prevalence of taper damage in modular TKA components. 198 modular components were revised after 3.9±4.2y (range: 0.0–17.5y). Modular components were evaluated for fretting corrosion using a semi-quantitative 4-point scoring system. Flexural rigidity, stem diameter, alloy coupling, patient weight, age and implantation time were assessed as predictors of fretting corrosion damage. Mild-to-severe fretting corrosion (score≥2) was observed in 94/101 of the tapers on the modular femoral components and 90/97 of the modular tibial components. Mixed alloy pairs (p=0.03), taper design (p<0.001), and component type (p=0.02) were associated with taper corrosion. The results from this study supported the hypothesis that there is taper corrosion in TKA. However the clinical implications of fretting and corrosion in TKA remain unclear.

Keywords: TKA, Corrosion, Modular

Introduction

Over the past three decades, fretting and corrosion of modular taper connections has been studied in the context of total hip arthroplasty (THA)[1]. While a considerable amount of research has been conducted to determine the prevalence and associated factors of fretting corrosion for modular junctions in THA [1–8], comparatively little is known about the risk of fretting corrosion in components for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [9]. In the cases of instability or revision TKA, contemporary designs may include one or more modular connections. Modularity affords the surgeon greater flexibility to restore knee function and stability for the patient. Thus, modularity is employed in TKA, although to a lesser extent than in THA.

In TKA, most of the literature pertaining to metal release involved failed implants (wear through of the polyethylene, improper fixation, etc.) and corrosion not associated with mechanically assisted crevice corrosion at the taper interface [9–15]. This release can have different adverse effects depending on metal type and quantity [12]. However, alloys that are commonly used in TKA have been studied and noted to have adverse and toxic effects [10–15]. More specifically cobalt, chromium and nickel have been studied to determine effects of ion release [14, 15]. In one study involving a CoCr TKA, slightly increased ions in serum and urine were noted after 6–120 weeks. Two patients with loose implants had a substantial increase of Co ions after 7 weeks[14]. Jacobs et al. observed titanium ion release in cementless TKA and linked this observation with osteolysis, cutaneous allergic reactions and remote site accumulations of ions. The large release of Ti was attributed to implant damage either involving improper fixation, wearing through the polyethylene insert, or damage from a carbon fiber reinforced polymer insert [10]. Breen et al. observed metal ion debris subsequent to implant damage in 3 patients that resulted in tumors containing metal ions[11]. A separate study involving cemented TKA implants noted metal ion release through observation of urine samples. [16]. Only recently has metal release in TKA been associated taper junction corrosion. McMaster et al. reported a case study of adverse local tissue reaction (ALTR) in TKA that was attributed to severe corrosion of a mixed metal Morse taper junction [9]. Mixed metal combinations have been shown to increase fretting corrosion, which is thought to be due to the gradients present in the synovial fluid and across the different metals [6, 9]. This study of adverse local tissue reactions around a modular connection in TKA prompted us to review our knee retrieval collection for evidence of taper corrosion and metal release into the surrounding tissues.

During this study, we asked the question: What is the incidence of fretting corrosion and taper damage in modular TKA components? We hypothesized that modular taper connections in TKA would be exhibit taper fretting and corrosion, similar to the modular connections in THA. Additionally we asked: What patient and implant factors influence the extent and severity of fretting and corrosion damage in modular TKAs? In order to answer these questions we performed a retrieval analysis of 198 modular TKA components was conducted on the modular surfaces in tibial and femoral junctions.

Methods

Implant and Clinical Information

Modular total knee replacement systems were consecutively retrieved at 144 revision surgeries between 2000 and 2013 as part of an IRB-approved, multi-institutional implant retrieval program which included 6 clinical revision centers in collaboration with two university-based biomedical engineering departments. The 198 components from these revision surgeries were implanted for 3.8±4.2 years (range: 0 to 17.5 years). The collection included the designs from 5 major manufacturers: Biomet (Warsaw, Indiana; n=11/198), Depuy (Warsaw, Indiana; n=47/198), Stryker (Mahwah, New Jersey; n= 49/198), Smith and Nephew (Memphis, Tennessee; n= 16/198), Zimmer (Warsaw, Indiana; n= 69/198), as well as other manufacturers (n=6/198). One hundred one (101) of the components were femoral components and 97 were tibial components. Ninety (90) of the components had a threaded taper junction and 108 of the components had a conical taper junction.

Clinical information, including age, gender, revision reason, and implantation time was obtained for each implant. Additionally intraoperative notes were reviewed for each revision surgery. The most prevalent reasons for revision were infection (n=86/198), loosening (n=45/198), instability (n= 27/198) and stiffness (n=6/218). Five of the cemented systems had an intraoperative report of metallosis; however these systems were not revised for reactions to the debris. In all 5 cases, the polyethylene bearing was intact and not worn through. Additional factors that were observed were cemented components (n=195/198) and mixed metal couplings (n=93/198). Cemented components were indicated in the operative notes and by inspection of the device and radiographs.

Fretting and Corrosion Evaluation

The modular components were disassembled and photographed in their received condition. Components were then cleaned by two 20-minute soaks in a 1: 10 ratio of detergent (Discide®; AliMed, Dedham, Massachusetts) to water. Components were placed in an ultrasonication for two consecutive 30-minute periods in de-ionized water. After cleaning, the tapers were inspected using a stereomicroscope for evidence of fretting and corrosion damage.

Damage at the interior of the modular junctions was characterized using a modified semi-quantitative method adapted from the work of Goldberg [5]. The scoring criterion was separated into four groups describing minimal, mild, moderate and severe damage (Figure 1). The score of 1 was assigned for minimal damage, in which fretting occurred on less than 10% of the surface area with no visible corrosion damage. The score of 2 was assigned for mild damage in which fretting occurred on more than 10% of the surface and corrosion attack to one or more small areas. A score of 3 was associated with moderate damage in which fretting occurred on more than 30% of the surface area with an aggressive local corrosion attack with corrosive debris. A score of 4 was associated with severe damage in which fretting occurred on more than 50% of the surface area with severe corrosion attack and an abundance of corrosive debris. Each component was scored by three independent investigators (C.A., M.T, and D.W.M.) Any discrepancies among the users were resolved in a conference between the investigators, resulting in one final score.

Figure 1.

Example femoral condyle stereomicrographs illustrating the scoring system used to evaluate fretting corrosion in modular TKA (A). Example femoral stem stereomicrographs illustrating the scoring system used to evaluate fretting corrosion in modular TKA (B).

Decreased flexural rigidity has been associated with increased fretting corrosion in THA[4, 5, 17]. Thus, flexural rigidity was calculated for each taper junction. The stem diameter was measured where the male taper exited its mating surface. The metallurgical composition of each component was determined using X-ray fluorescence (Niton XL3t GOLDD+; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). Flexural rigidity was calculated by multiplying the elastic modulus and the 2nd moment of area [5].

Statistical Analysis

Non-parametric statistical tests were performed due to the nonparametric nature of the data using commercial statistical software (JMP 10.0, Cary, NC). We investigated several factors that had previously been found to be associated with fretting corrosion in THA including: metal alloy coupling, component type (femoral vs. tibial), taper design (conical vs. threaded), flexural rigidity, and patient factors. For categorical variables, differences in corrosion scores were assessed using the Wilcoxon test. To determine if fretting corrosion scores correlated with continuous variables, we relied on the Spearman Rank Correlation Test. The level of significance was p < 0.05.

Results

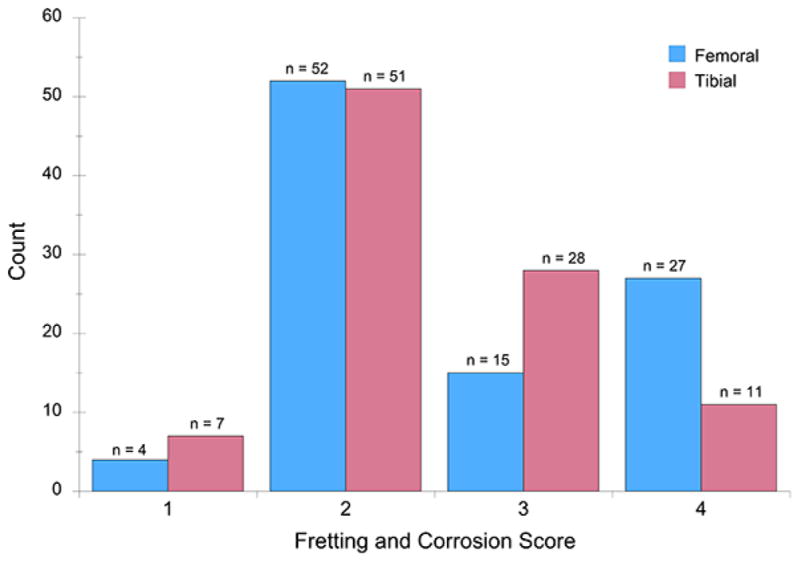

Evidence of taper damage was a common finding in the modular interfaces. Mild to severe damage (score >= 2) was observed in 94 of the 101 (93%) femoral implants and 90 of the 97 (93%) tibial implants (Figure 2). Severe damage (score = 4; Figure 3) was observed in 27 femoral implants and 11 of the tibial implants. Although examples of severe corrosion were observed in both conical and threaded taper designs, overall, conical tapers exhibited significantly higher fretting and corrosion scores than the threaded taper junctions (mean difference = 1.0 and 1.0; p<0.001 for both male and female taper junctions, respectively; Figure 4). Thus, for the remainder of the analysis, these cohorts were treated separately.

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing the prevalence of fretting and corrosion, through a semi quantitative scoring method, in TKA separated by anatomical location.

Figure 3.

Case study of a modular femoral implant with mismatched alloy coupling with a male taper (A) and female taper (B) fretting and corrosion score of 4. It was implanted for 7.75 years.

Figure 4.

Box plot depicting differences between conical and threaded taper junctions with respect to fretting and corrosion score. The male and female tapers were depicted separately.

For the conical tapers it was noted that alloy coupling, anatomical location and flexural rigidity were associated factors. For male conical tapers, mixed alloy couples had higher fretting corrosion scores than the matched alloy couples (mean difference = 0.4; p = 0.03). One case (Figure 3) had a severe fretting and corrosion (score of 4) after being implanted for 7.75 years implants. The anatomical location (i.e. tibial component vs. femoral component) was also a significant factor for fretting corrosion. Specifically, for the male tapers, the femoral components had higher corrosion scores that the tibial components (p=0.02). The flexural rigidity of the female tibial conical tapers was negatively correlated with fretting corrosion scores (Spearman’s Rho = −0.33; p=0.04). However, patient factors (implantation time, patient weight, age) and stem diameter were not associated factors (p>0.05).

Decreased flexural rigidity and stem diameter were associated factors for the threaded taper connections. Flexural rigidity was negatively correlated with fretting corrosion of the tibial components (Spearman’s Rho ≤ −0.36, p < 0.02). Similarly, the stem diameter of tibial components was negatively correlated with corrosion scores (Spearman’s Rho < −0.31, p ≤ 0.03). Patient weight was positively correlated with tibial corrosion scores (Spearman’s Rho > 0.35, p ≤ 0.03). Anatomical location, alloy coupling, implantation time, and patient age were all unassociated with fretting corrosion scores (p > 0.05).

Discussion

This retrieval study observed the prevalence of fretting and corrosion in TKA modular knee implants. Although taper damage was observed in the late 20th century in THA [1, 6, 8], to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first large-scale retrieval study investigating fretting and corrosion damage in modular TKA. The results of this study support the hypothesis that modular taper connections in TKA exhibit taper fretting and corrosion mechanisms, similar to the modular connections in THA.

There were several limitations to this study. First, we used a semi-quantitative method to evaluate the damage at the taper interfaces. Inter-observer variability of the scoring process was addressed by involving three investigators, including an investigator with experience evaluating retrieved modular connections in THA (DWM). Although taper damage scoring technique cannot be used to infer metal debris release from the taper, the benefit of using damage scores is that it permits comparison with previous retrieval studies of taper corrosion in the THA literature [4, 5]. Despite the limitation of using damage scores, we found it to be a useful technique to classify the severity of fretting and corrosion and the first step in assessing our retrieval collection for future, quantitative analysis. Another limitation for this study was its basis on retrieved knee components, none of which were revised for adverse reactions to metal debris. Thus, we were studying clinically failed devices and not well functioning devices. However, the extent of corrosion was not correlated with the reasons for revision. Third, we based our assessment of metal release and ALTRs on a retrospective review of the operative records. We cannot rule out that low grade ALTRs were misidentified as infection or unexplained pain, as has been suggested by previous authors in the case of THA[18]. Fourth, the study was limited to TKA designs involving a modular taper, and thus our results are not applicable to the majority of primary TKAs implanted in the US which to not include a modular connection. On the other hand, our finding of nearly ubiquitous taper fretting and corrosion in modular TKAs, typically employed for revision knee patients, calls attention to the potential role of metal release for the most vulnerable population of TKA recipients.

The prevalence of fretting and corrosion damage has been widely discussed in the literature regarding THA [1–6, 8, 19]. However, this topic has not been studied in detail in TKA, making comparison of our study to the literature difficult. One case study on modular TKA described an instance of ALTR subsequent to taper corrosion. The implant was a mixed metal conical taper combination. The main finding at the site was “black encrustations” of the proximal stem and the femoral component[9]. In this study, severe corrosion (Score = 4) was observed in 25/56 (45%) femoral implants having conical taper connections and 11/52 (21%) of the tibial implants with conical taper connections. In contrast with the case study, none of the knee revisions in our series of retrieved components was revised due to metal release or ALTRs.

The reported factors that correlated with increased fretting and corrosion scores in modular TKA shares similarities to previous findings from retrieved modular THAs. Mixed alloys and decreased flexural rigidity were linked with the increase in fretting corrosion scores. The decreased elastic modulus of Ti-Al-V may allow for more micromotion, which can damage the passivation layer coating implants leading to galvanic corrosion. This is also expressed as a result of fretting where the passive layer is damaged and left in an aqueous environment [2, 5, 8]. Because it is more flexible it is more susceptible to being damaged by fretting which is a precursor to a corrosive attacks [5]. In this study, we observed that the conical taper designed modular junction was associated with higher corrosion scores as compared to the threaded junctions. It is hypothesized that this is due to the threaded connection enabling less micromotion between the surfaces than the conical tapers. One factor that was associated with increased fretting corrosion was the anatomical location. Femoral implants had a higher fretting and corrosion scores compared to tibial trays. This could be in part due to the nature of femoral condyles being composed of CoCr. Thus, a majority of the femoral components in this study were mixed alloy combinations. Additionally the biomechanics at the taper interface may be different in the femur as opposed to the tibia. However, this was outside the scope of the current study. Further investigation of these factors is warranted.

In summary, the results of the current study show that fretting and corrosion is prevalent in modular TKA. As observed in modular THAs, implant factors such as mismatched metals, location and flexural rigidity are factors contributing to high fretting and corrosion scores. Additionally the taper design and stem diameter were also linked factors in the prevalence of severe fretting and corrosion score. The clinical implications of fretting and corrosion for TKA remain unclear, because modularity in TKA is typically reserved for unstable or revised knees. The majority of TKAs were cemented, which may also limit the diffusion of corrosion products. Based on our findings of the prevalence of fretting corrosion, additional research should be conducted to elucidate additional factors and clinical implications of mechanically assisted crevice corrosion in modular TKA.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH R01 AR47904.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAMS) R01 AR47904. Institutional support has been received from Stryker, Zimmer, Invibio, and Formae.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that the institution where the work was performed approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Implant Research Center at Drexel University.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacobs JJ, Gilbert JL, Urban RM. Current Concepts Review-Corrosion of Metal Orthopaedic Implants. The journal of bone & joint surgery. 1998;80(2):268. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199802000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer H, Mueller T, Goldau G, Ruetschi M, Lohmann CH. Corrosion at the cone/taper interface leads to failure of large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2012;470(11):3101. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2502-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kretzer JP, Jakubowitz E, Krachler M, Thomsen M, Heisel C. Metal release and corrosion effects of modular neck total hip arthroplasty. International orthopaedics. 2009;33(6):1531. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0729-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgs GB, Hanzlik JA, Macdonald DW, Gilbert JL, Rimnac CM, Kurtz SM the Implant Research Center Writing C. Is Increased Modularity Associated With Increased Fretting and Corrosion Damage in Metal-On-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty Devices?: A Retrieval Study. J Arthroplasty. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg JR, Gilbert JL, Jacobs JJ, Bauer TW, Paprosky W, Leurgans S. A multicenter retrieval study of the taper interfaces of modular hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat R. 2002;401:149. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert JL, Buckley CA, Jacobs JJ. In vivo corrosion of modular hip prosthesis components in mixed and similar metal combinations. The effect of crevice, stress, motion, and alloy coupling. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(12):1533. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garbuz DS, Tanzer M, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP. The John Charnley Award: Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing versus large-diameter head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2010;468(2):318. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1029-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collier JP, Surprenant VA, Jensen RE, Mayor MB. Corrosion at the interface of cobalt-alloy heads on titanium-alloy stems. Clin Orthop Relat R. 1991;271:305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMaster WC, Patel J. Adverse Local Tissue Response Lesion of the Knee Associated With Morse Taper Corrosion. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2013;28(2):375.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JJ, Silverton C, Hallab NJ, Skipor AK, Patterson L, Black J, Galante JO. Metal release and excretion from cementless titanium alloy total knee replacements. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1999;358:173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breen D, Stoker D. Titanium lines: a manifestation of metallosis and tissue response to titanium alloy megaprostheses at the knee. Clinical radiology. 1993;47(4):274. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wapner KL. Implications of metallic corrosion in total knee arthroplasty. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1991;271:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stulberg B, Watson J, Shull S, Merritt K, Crowe T, Stulberg S, Guidry C. Metal ion release after porous total knee arthroplasty: A prospective controlled assessment. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1987;33:314. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunderman FW, Hopfer SM, Swift T, Rezuke WN, Ziebka L, Highman P, Edwards B, Folcik M, Gossling HR. Cobalt, chromium, and nickel concentrations in body fluids of patients with porous-coated knee or hip prostheses. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1989;7(3):307. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergschmidt P, Bader R, Mittelmeier W. Metal hypersensitivity in total knee arthroplasty: Revision surgery using a ceramic femoral component—A case report. The Knee. 2012;19(2):144. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazzaglia UE, Minoia C, Gualtieri G, Gualtieri I, Riccardi C, Ceciliani L. Metal ions in body fluids after arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 1986;57(5):415. doi: 10.3109/17453678609014760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz SM, Kocagoz SB, Hanzlik JA, Underwood RJ, Gilbert JL, Macdonald DW, Lee GC, Mont MA, Kraay MJ, Klein GR, Parvizi J, Rimnac CM. Do Ceramic Femoral Heads Reduce Taper Fretting Corrosion in Hip Arthroplasty? A Retrieval Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meneghini RM, Hallab NJ, Jacobs JJ. Evaluation and treatment of painful total hip arthroplasties with modular metal taper junctions. Orthopedics. 2012;35(5):386. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120426-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langton D, Jameson S, Joyce T, Gandhi J, Sidaginamale R, Mereddy P, Lord J, Nargol A. Accelerating failure rate of the ASR total hip replacement. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2011;93(8):1011. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.26040. British Volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]