Abstract

With the perspective of functional myocardial regeneration, we investigated small cardiomyocytes bordering on microdomains of fibrosis, where they are dedifferentiated re-expressing fetal genes, and determined: i) whether they are atrophied segments of the myofiber syncytium; ii) their redox state; iii) their anatomic relationship to activated myofibroblasts (myoFb), given their putative regulatory role in myocyte dedifferentiation and re-differentiation; iv) the relevance of proteolytic ligases of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a mechanistic link to their size; and v) whether they could be rescued from their dedifferentiated phenotype. Chronic aldosterone/salt treatment (ALDOST) was invoked, where hypertensive heart disease with attendant myocardial fibrosis creates the fibrillar collagen substrate for myocyte sequestration with propensity for disuse atrophy, activated myoFb and oxidative stress. To address phenotype rescue, 4 wks ALDOST was terminated followed by 4 wks neurohormonal withdrawal combined with a regimen of exogenous antioxidants, ZnSO4 and nebivolol (assisted recovery). Compared to controls, at 4 wks ALDOST we found small myocytes to be: 1) sequestered by collagen fibrils emanating from microdomains of fibrosis and representing atrophic segments of the myofiber syncytia; 2) dedifferentiated re-expressing fetal genes (β-myosin heavy chain and atrial natriuretic peptide); 3) proximal to activated myoFb expressing α-smooth muscle actin microfilaments and angiotensin-converting enzyme; 4) expressing reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide (NO) with increased tissue 8-isoprostane, coupled to ventricular diastolic and systolic dysfunction; and 5) associated with upregulated redox-sensitive, proteolytic ligases MuRF1 and atrogin-1. In a separate study, we did not find evidence of myocyte replication (BrdU labeling) or expression of stem cell antigen (c-Kit) at wks 1-4 ALDOST. Assisted recovery caused: complete disappearance of myoFb from sites of fibrosis with re-differentiation of these myocytes; loss of oxidative stress and UPS activation, with restoration of NO and improved ventricular function. Thus, small dedifferentiated myocytes bordering on microdomains of fibrosis can re-differentiate and represent a potential source of autologous cells for functional myocardial regeneration.

Keywords: cardiomyocytes, atrophy, fibrosis, aldosteronism

Introduction

Cell-based therapies aimed at myocardial regeneration have gained considerable momentum. They include: i) an endogenous pool of pluripotent cardiac stem cells (1); and ii) bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (2). Herein, we set forth the beginnings of a complementary strategy. It entails autologous cardiomyocytes bordering on microdomains of fibrosis, where they remain viable, but sequestered by tendrils of fibrillar collagen emanating from microscopic scars and perivascular fibrosis. They have dedifferentiated, re-expressing fetal genes that include β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) (3-7). Sequestered and dedifferentiated cardiomyocytes are small (<1000 μm2) (6, 8) comparable in size to atrophic cells seen with hemodynamic unloading that accompanies heterotopic transplantation, banding the thoracic segment of the inferior vena cava, or a period of mechanical circulatory support (9-11). Other interventions which reduce ventricular work to invoke cardiac atrophy include prolonged bed rest and weightlessness of zero gravity (12). Generalized cardiomyocyte atrophy also accompanies dietary caloric restriction (13) or taurine deficiency (14), dexamethasone treatment (15), sympathetic neuron ablation (16), or cachexia of malignancy (17). Localized cardiomyocyte atrophy, on the other hand, is observed at sites where fibrillar collagen normally envelops myocytes (e.g., insertion of mitral valve leaflets or emergence of chordae tendineae from papillary muscle) (4-6), or at sites of fibrosis commonly present with pressure overload (4, 5), hypertensive heart disease (6, 18-21) or following myocarditis (22). Myocytes ensnared by stiff fibrils of collagen have an imposed workload reduction and, therefore, predisposition to disuse atrophy (6, 23). Foci of scarring, which are widely scattered throughout the failing heart (24), and with attendant atrophy of neighboring myocytes inevitably contribute to diastolic and systolic ventricular dysfunction, respectively.

We sought to examine: a) whether small, dedifferentiated myocytes are, in fact, atrophied segments of the myofiber syncytium; b) the redox state of these myocytes; c) their anatomic relationship to activated myofibroblasts (myoFb), given their putative regulatory role in myocyte dedifferentiation and re-differentiation (25, 26); d) the relevance of prooxidant-based activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) with its proteolytic E3 ligases, MuRF1 and atrogin-1, in localized atrophy and which are known to account for the generalized cardiomyocyte atrophy seen with reductions in ventricular work or dexamethasone treatment or when skeletal muscle is immobilized (15, 16, 27-32); and e) whether sequestered small myocytes could be rescued from their dedifferentiated phenotype and ventricular dysfunction improved with an ultimate goal toward functional myocardial regeneration. Finally, to address whether these small dedifferentiated myocytes bordering on microdomains of fibrosis represent endogenous cardiac stem cells expressing c-Kit antigen and have a replicative potential (BrdU labeling), as has been suggested for mitotic cells found at the periphery of an infarct scar (33), we conducted a separate study at wks 1-4 ALDOST.

We hypothesized a cell-based strategy targeting microdomains of fibrosis, where resident myofibroblasts and their autocrine/paracrine signaling are eliminated while sequestered, small dedifferentiated myocytes, ensnared by collagen fibrils and subject to disuse atrophy, are rescued and re-differentiated toward regeneration of functional myocardium. Toward this end, we examined the hypertensive heart disease that accompanies 4 wks aldosterone/salt treatment (ALDOST), where a mitochondriocentric prooxidant pathway to myocyte necrosis with ensuing reparative fibrosis, or scarring, and perivascular fibrosis of intramural coronary vasculopathy create the substrate for myocyte sequestration, activated myoFb and where oxidative stress emanating from subsarcolemmal mitochondria is operative (6, 8, 34-37). To rescue the dedifferentiated myocyte phenotype, the 4-wk ALDOST regimen was discontinued and a 4-wk period of neurohormonal withdrawal was combined with a pharmacoregenerative strategy aimed at accelerating the restoration of redox equilibrium. Termed assisted recovery, it included: i) an oral Ca2+, Mg2+ and Zn2+ supplement for 4 days to restore their serum levels which had declined in response to marked urinary and fecal excretory losses, and consequent ionized hypocalcemia accounting for secondary hyperparathyroidism with parathyroid hormone-mediated myocyte and mitochondrial Ca2+ overloading and attendant oxidative stress (38, 39); ii) 4 wks of oral ZnSO4 to enhance endogenous Zn2+-based antioxidant defenses that aided in the recovery of atrophic myocytes (6, 40); and iii) 4 wks oral nebivolol, a β1 adrenergic receptor antagonist with additional properties as a β3 receptor agonist which, in turn, promotes nitric oxide (NO) generation and consequent NO-based release of inactive Zn2+ bound to metallothionein-1 and where increased cytosolic free [Zn2+]i further raises these defenses (41, 42).

METHODS

Animal Model

Eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were used throughout this series of experiments approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of our institution. As reported previously and following uninephrectomy, an osmotic minipump containing aldosterone was implanted subcutaneously to raise its circulating levels to those commonly found in human CHF and which suppress circulating renin activity and angiotensin II (38). Drinking water was fortified with 1% NaCl and with 0.4% KCl to prevent hypokalemia. Following 4 wks ALDOST, implanted pumps were removed, drinking tap water restored, and standard laboratory chow made available for 4 wks. This period of recovery included a cation supplement, ZnSO4 and nebivolol as antioxidants. The oral cation supplement consisted of CaCl2 (2.1 g/day), MgCl2 (0.42 g/day) and ZnCl2 (0.28 g/day) given for 4 days. ZnSO4 (40 mg/day by gavage) and nebivolol (10 mg/kg/day by gavage) were given for 4 wks. Unoperated, untreated age-/sex-/strain-matched rats served as controls. Each group consisted of 6 rats. Animals were killed at weeks 4 and 8 with each regimen with body weight determined thereafter. A separate study was performed to assess stem cell (c-Kit) antigen expression and potential for myocyte replication. Rats were treated with ALDOST for wks 1, 2, 3 and 4 (n=6/group/time point). For myocyte proliferation, rats received BrdU infusion (2 mg/day by implanted minipump) begun 1 wk before termination. Heart tissue was harvested for immunohistochemistry at each weekly interval.

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Measurements

Blood pressure (BP) and heart rate were measured at wk 4 ALDOST and 4 wks recovery as previously reported (6). Animals were acclimated for three days before BP was taken.

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed with 7.0 MHz pediatric transducer in anesthetized rats. Parasternal short axis 2-D and M-mode views were acquired at the level of papillary muscles. Left ventricular mass, fractional shortening and E/A ratio were calculated as previously reported (6).

Cardiac Morphology

Cardiac morphology was assessed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The presence of fibrosis was assessed by collagen-specific picrosirius red staining in coronal sections (6 μm) of the ventricles and observed by light microscopy with or without polarized light as previously reported (43).

Quantitative In Vitro Autoradiography: Cardiac Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Binding Density

The radioligand used to label ACE was [125I]351A, a tyrosyl derivative of lisinopril and potent competitive inhibitor of ACE. 351A was iodinated by the chloramine T method and separated from free 125I by SP Sephadex C25 column chromatography as previously reported (44-46). Cryostat sections (20μm) were incubated in phosphate buffer containing [125I]351A [0.3 μCi/mL (~300 pM)] for 1 h at 20°C. Following incubation, sections were washed, dried, placed in X-ray cassettes, and exposed to Kodak NMB-6 film for 3 days.

Flow Cytometry

Rat cardiomyocytes were obtained by retrograde collagenase perfusion (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Flow cytometry was used to detect cardiomyocytes producing NO or reactive oxygen species (ROS) using DAF-FM diacetate or CellROX®, respectively (Life Technologies). Live cardiomyocytes were positively identified with a rabbit antibody to β1 adrenergic receptor (Abcam Biochemicals, Cambridge, MA) followed by APC-goat anti-rabbit IgG and exclusion of propidium iodide (PI) as previously reported (6). Flow cytometry gating in histograms was in the following order: PI negative, β1 adrenergic receptor-positive, and ROS- or NO-positive. Labeled cells were analyzed in the UTHSC Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Laboratory with a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Cardiac 8-Isoprostane

Cardiac tissue total 8-isoprostane (free and esterified) was measured using a competitive enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) as reported previously (47).

Western Blotting

For immunoblotting, cardiac myocytes were lysed with SDS-urea buffer (40 mM Hepes, 4 M urea, 1% SDS, pH 7.4). Protein content was measured with bicinchoninic acid assay method (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) as previously reported (6).

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

For immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining, 6 μm thick frozen sections were fixed in 10% formalin, blocked with 3% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies against α-smooth muscle actin, β-MHC, ANP, BrdU or c-Kit, followed by secondary antibody incubation as previously reported (6).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons between groups were performed with one-way ANOVA using Scheffé's post-hoc analysis. Frequency distributions in cell size were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Systemic Responses

Young adult, 8-wk-old male Sprague-Dawley rats given 4 wks ALDOST gradually developed anorexia associated with cachexia, expressed as impaired gain in body weight (p<0.05), as contrasted to age-/sex-matched, untreated controls (see Figure 1, upper left panel). Following 4 wks of assisted recovery, body weight returned to levels comparable to controls.

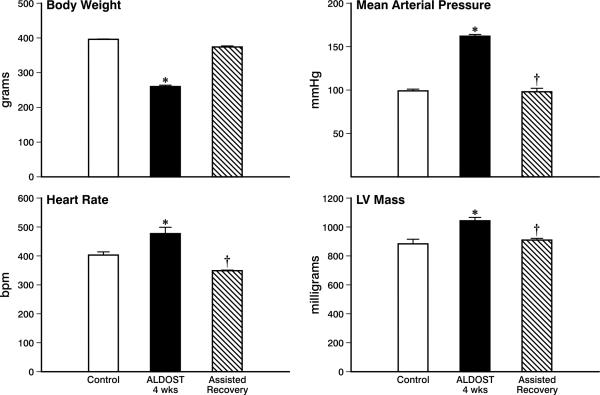

Figure 1.

Systemic responses to 4 wks aldosterone/salt treatment (ALDOST), followed by 4 wks of assisted recovery which consisted of the withdrawal of ALDOST coupled with a Ca2+, Mg2+ and Zn2+ supplement for 4 days and ZnSO4 and nebivolol cotreatment for 4 wks. *p<0.05 ALDOST vs. control; †p<0.05 assisted recovery vs. ALDOST. See text for details. LV, left ventricle.

Over the course of weeks, arterial pressure rose to hypertensive levels during ALDOST. As seen in the upper right panel, Figure 1, at 4 wks mean arterial pressure was significantly (p<0.05) increased above that found in untreated controls and was restored to control levels after 4 wks ALDOST withdrawal and assisted recovery.

Heart rate rose significantly (p<0.05) during 4 wks ALDOST (see Figure 1, lower left panel). During assisted recovery and which included nebivolol treatment, heart rate fell below control values (p<0.05) as has been previously reported for the dose used (42).

Cardiac Pathology

Left ventricular (LV) mass rose significantly (p<0.05) during 4 wks ALDOST (see Figure 1, lower right panel) in keeping with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in response to left ventricular pressure overload that accompanies arterial hypertension. Thereafter, and coupled with the return in arterial pressure to control levels, there was a regression in LV mass and which at 4 wks recovery was comparable to levels found in controls.

Light microscopic examination of the myocardium at 4 wks ALDOST confirmed the presence of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Moreover, there were widely scattered foci of fibrosis throughout the right and left heart morphologically expressed as microscopic scars and perivascular fibrosis of intramural coronary arteries (see Figure 2). Using fibrillar collagen-specific histochemical staining with picrosirius red, an area of myocardial scarring is seen at the top center of panel A while a site of perivascular fibrosis is at its center. Arrowheads identify small myocytes of variable size sequestered at these sites of fibrosis. These small and smaller myocytes bordering on the scar are not a series of cellular islands, or archipelago, located in an expanse of fibrous tissue. Instead, they are atrophied segments of myofiber syncytia. As seen in panel B, arrowheads identify atrophied segments of the myofiber and small arrows identify cells in close proximity to these atrophic myocytes. In panel C, polarized light imaging of picrosirius red-stained tissue identifies the fibrillar collagen meshwork and collagen fibrils that ensnare atrophic myocytes which have lost their cross-striations (arrowheads). Normal-sized myofibers, free of entrapment, retain their size and cross-striations. Panel D is a schematic representation of normal and atrophied myocytes of the myofiber syncytium, where atrophied cells are ensnared by fibrillar collagen of scar tissue and where a myofibroblast is in close proximity to such a smaller myocyte.

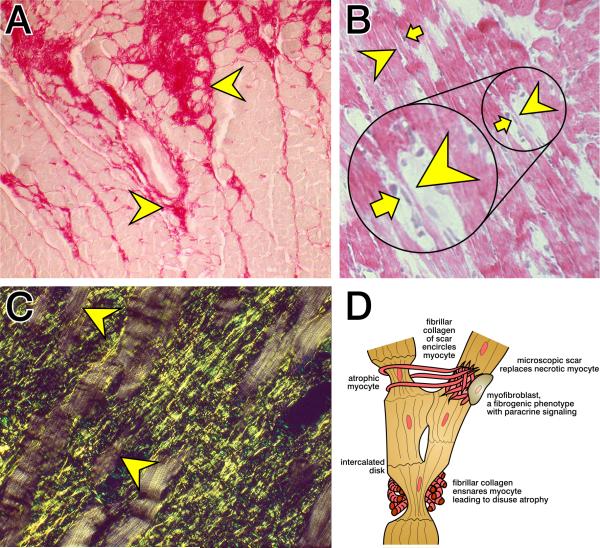

Figure 2.

Cardiac histopathology at 4 wks ALDOST. A) Picrosirius red staining of fibrillar collagen found in a coronal section of left ventricle (×200). Illustrated are the fibrillar collagen composition of a microscopic scar (top center) and perivascular fibrosis of intramural coronary artery (middle center). Arrowheads indicate small cardiomyocytes of variable size surrounded by fibrillar collagen at these respective sites. B) Longitudinal perspective of myofiber syncytia. Arrowheads indicate atrophied cells of variable size of this myofiber syncytia while arrows identify cells juxtaposed to these atrophied myocytes. H&E stain (×200). C) Picrosirius red stain plus polarized light (×400). The yellow-green fibrillar collagen meshwork of microscopic scars is seen as they ensnare atrophied segments of myofibers (arrowheads) which have lost their cross-striations. See text. D) A schematic representation of normal and atrophic myocytes of the myofiber syncytium and where collagen fibrils emanating from a microscopic scar encircle myocytes. Ensnared myocytes are smaller and subject to disuse atrophy. An activated myofibroblast with a fibrogenic phenotype is seen in proximity to an atrophied myocyte. See text for details.

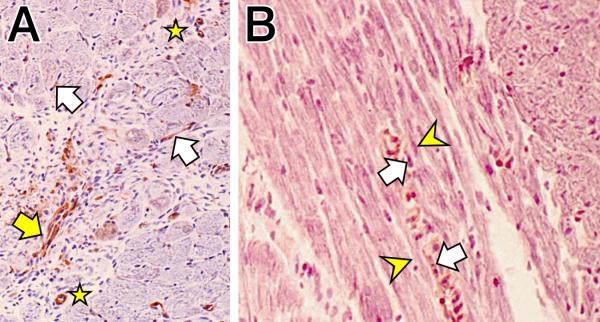

Activated fibroblast-like cells, responsible for fibrous tissue formation following tissue injury, express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and accordingly have been termed myofibroblasts. By immunohistochemistry and as seen in panel A, Figure 3, these myoFb are present at a site of tissue repair (yellow arrow); they also are in close proximity to myocytes (white arrows). In panel B, Figure 3, these α-SMA-positive cells (white arrows) are juxtaposed with atrophied myocytes (yellow arrowheads). This juxtaposition of myoFb with atrophied myocytes raises the prospect of heterocellular signaling between these cells, as well as their heterocellular coupling by gap junctions. These issues will be addressed in future studies.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry. A) Alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive cells of small coronary arterioles (stars) and myofibroblasts (white arrows) adjacent to cardiomyocytes at 4 wks ALDOST (×200). The yellow arrow identifies a cluster of myofibroblasts seen at a site of tissue repair. B) White arrows point to α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts juxtaposed to atrophied segments of myofibers (yellow arrowheads) (×400).

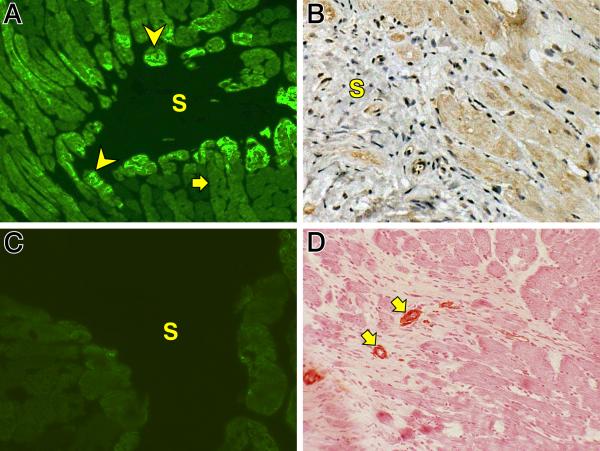

Atrophic myocytes re-express fetal genes, including β-MHC and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) (see Figure 4). As seen in panel A, myocytes bordering on a microscopic scar(s) re-express β-MHC (arrowheads) as contrasted to its low level expression in myocytes distant to the scar (arrow). In panel B myocytes bordering on a scar (S) are seen to re-express ANP. We found no evidence of myocyte replication by BrdU labeling or expression of c-Kit stem cell antigen during wks 1, 2, 3 and 4 ALDOST. Following the 4-wk period of assisted recovery, the re-expression of these fetal genes at sites of fibrosis returned to control levels in keeping with a rescued phenotype as seen in panel C for β-MHC gene expression at a microscopic scar (S). Furthermore, α-SMA-positive myoFb were no longer present at sites of fibrosis after 4 wks assisted recovery, where only vascular smooth cells of intramural coronary arteries were so labeled (arrows) (see panel D). The complete disappearance of myoFb is coincident with the re-differentiation of myocytes and loss of fetal gene expression. This further suggests a potential crosstalk between these cells.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry. A) Re-expression of β-myosin heavy chain in cells (arrowheads) bordering on a microscopic scar (S) seen at 4 wks ALDOST. The arrow identifies low level expression of this contractile protein in cells remote to the scar. B) Re-expression of atrial natriuretic peptide by myocytes adjacent to a scar (S) (×200). C) Return to low level expression of β-myosin heavy chain is seen at site of microscopic scar (S) at 4 wks of assisted recovery. D. α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts are no longer seen at site of scar at 4 wks of assisted recovery. Only vascular smooth muscle cells of small arterioles (arrows) are positively labeled (×200).

In Vitro Quantitative Autoradiography

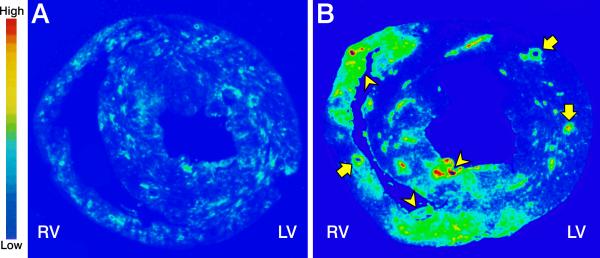

Compared to low-density ACE binding seen in a coronal section of control heart tissue (panel A, Figure 5), high-density ACE binding appears at 4 wks ALDOST and is anatomically coincident with foci of scarring (arrowheads) and perivascular fibrosis (arrows) as shown in panel B, Figure 5. Alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive myoFb are responsible for collagen fibrillogenesis at these fibrous tissue sites and they account for ACE expression.

Figure 5.

Autoradiographic low binding density for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) as seen on a coronal section for control heart tissue (panel A) and high-density binding at 4 wks ALDOST (panel B). Widely scattered microscopic scars (arrowheads pointing at green-yellow and red foci) and perivascular fibrosis of intramural coronary arteries (arrows pointing at circular vessels on cross-section) can be seen involving the right (RV) and left (LV) ventricular free walls and interventricular septum.

Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide

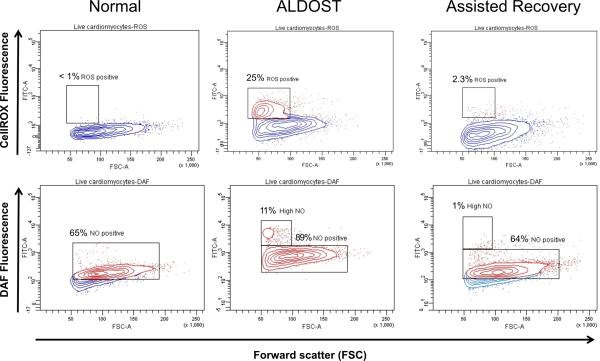

Biomarkers of ROS and NO were used, together with flow cytometry, to examine the redox state of cardiomyocytes harvested from control hearts, after 4 wks ALDOST and 4 wks assisted recovery. The top three panels of Figure 6 present ROS expression for these 3 groups. In control hearts shown in the top left panel, ROS expression was quite low at <1%, but increased substantially to 25% at 4 wks ALDOST and was primarily confined to smaller myocytes (red signals demarcated by the box seen in top middle panel). After 4 wks of assisted recovery, ROS expression returned essentially to control levels (top right panel), including that found in small myocytes.

Figure 6.

Flow cytometry. Intensity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) expression is shown in the top three panels while that of nitric oxide (NO) expression is shown in the bottom three panels. Top and bottom left panels are cardiomyocytes from normal untreated control rats (C), middle top and bottom panels at 4 wks ALDOST, and top and bottom right panels at 4 wks assisted recovery (AR). The contour plots present live cardiomyocytes in blue with ROS- and NO-positive cells in red. Y-axes are ROS- or NO-induced fluorescence (FITC). The X-axes are forward scatter (FCS). The percentages in the right and left plots are the percentages of ROS- or NO-positive cells. Percentages in the middle panels are the respective gated subpopulations. All of the cardiomyocytes in the ALDOST group expressed NO. See text for details.

Expression of NO for the 3 experimental groups are presented in the bottom three panels of Figure 6. NO expression was high in 65% of myocytes harvested from control hearts (red signals in lower left panel). After 4 wks of ALDOST, overall tissue NO expression was increased further to 89% of myocytes (lower middle panel) and markedly increased (11%) in smaller myocytes. These responses are likely due to the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase over the steady-state NO level present in control cardiomyocytes (48). Assisted recovery led to reversal in NO expression with 64% of cardiomyocytes (red signals in lower right panel) and 1% of small myocytes retaining high-level expression.

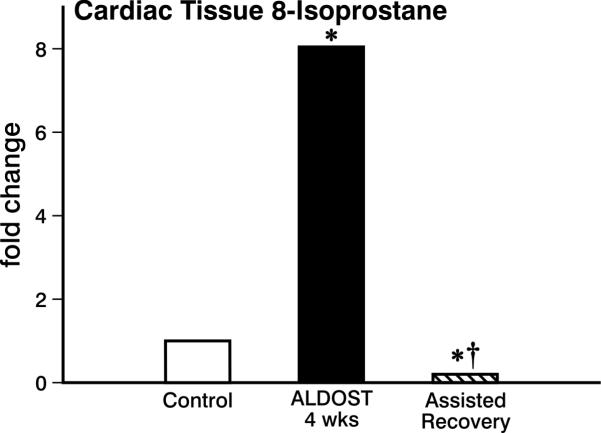

Compared to untreated controls, a significant rise in tissue 8-isoprostane, a biomarker of lipid peroxidation, was seen at 4 wks ALDOST (see Figure 7), which was not only abrogated but also diminished below control levels after the 4-wk regimen of assisted recovery that included exogenous antioxidants, ZnSO4 and nebivolol.

Figure 7.

Cardiac tissue 8-isoprostane expression, a marker of lipid peroxidation. Shown for controls and where it is markedly increased at 4 wks ALDOST (p<0.05) and completely attenuated by assisted recovery (†p<0.05), where it returned below controls (*p<0.05). See text for details.

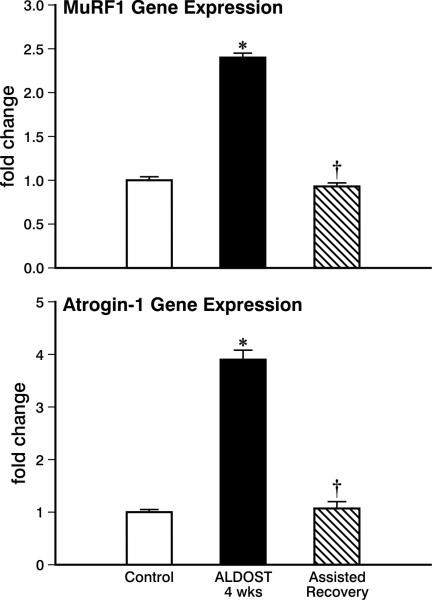

Expression of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Redox-sensitive proteolytic ligases, MuRF1 and atrogin-1, contribute to protein degradation. Their gene expression was markedly increased at 4 wks ALDOST, while returning to control levels at 4 wks assisted recovery (see Figure 8). These findings are in keeping with the appearance of myocyte atrophy and subsequent revitalization of these cells.

Figure 8.

Cardiac tissue expression of ubiquitin-proteasome system proteolytic ligases, MuRF1 and atrogin-1. In control hearts and where it is markedly increased at 4 wks ALDOST (*p<0.05), and returned to control levels (†p<0.05) at 4 wks of assisted recovery. See text for details.

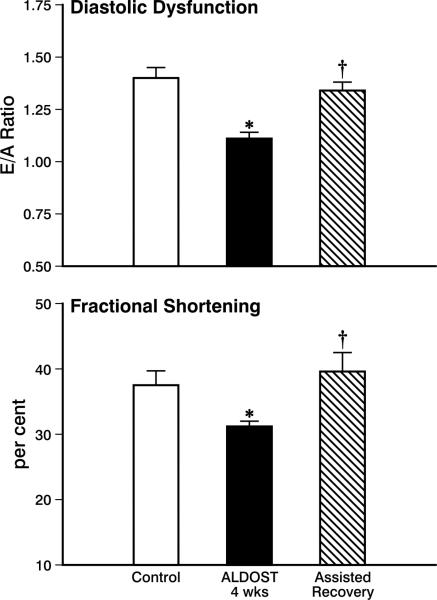

Ventricular Function

Echocardiographic interrogation of diastolic function was assessed by the E/A ratio. As seen in the top panel of Figure 9, this ratio was reduced (p<0.05) at 4 wks ALDOST. The fall in E, coupled to a rise in A, is in keeping with a stiffer-appearing left ventricle. These responses were reversed (p<0.05) and returned to control levels by the 4 wks period of assisted recovery. Systolic function, measured by echocardiography-based fractional shortening, was reduced (p<0.05) at 4 wks ALDOST returning to control levels at 4 wks of recovery (p<0.05) (see lower panel, Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular diastolic and systolic function using the E/A ratio to assess diastolic function and percent (or fractional) shortening as a measure of systolic function, respectively. Shown are values for controls, at 4 wks ALDOST, and upon 4 wks assisted recovery. *p<0.05 ALDOST vs. control; †p<0.05 assisted recovery vs. ALDOST. See text for details.

These reversible responses in ventricular diastolic and systolic function are concordant with the detrimental presence of oxidative stress at 4 wks ALDOST and favorable return in redox equilibrium with the upgrade in antioxidant defenses provided during assisted recovery.

DISCUSSION

Our study led to several major findings. First, in our model of chronic aldosteronism we found small cardiomyocytes bordering on microdomains of cardiac fibrosis, where they were sequestered by collagen fibrils, to represent atrophic segments of myofiber syncytia. Each myofiber consists of an anatomic syncytium, or in-series continuum of myocytes that abut one another and whose conjoint ends are forged together by intercalated disks (49). Within these disks are gap junctions (e.g., connexin 43) which facilitate electromechanical coupling between myocytes to create a functional syncytium. The presence of widely scattered sites of fibrosis throughout the right and left heart with their attendant atrophied myocytes compromises the heart's collective syncytium leading to reduced fractional shortening and longitudinal strain. Our flow cytometric findings suggest 10% of all harvested myocytes at 4 wks ALDOST are in the atrophic range, raising the prospect that these autologous myocytes represent a substantial source of cells toward myocardial regeneration and capable of improving systolic function.

Atrophied myocytes at sites of fibrosis are dedifferentiated re-expressing β-MHC. This fetal phenotype redirects metabolism toward a slower, less energy-demanding contractile protein further contributing to systolic dysfunction (50, 51). Dedifferentiated myocytes also re-express atrial natriuretic peptide with its negative inotropic properties . Others have reported on the re-expression of myocyte enhancer factor-2, a stress-responsive transcription activator and negative inotrope, at sites of fibrosis (50, 52-54). Hence, the pathologic structural remodeling of myocardium, coupled to the dedifferentiated cardiomyocyte phenotype, collectively contribute to the heart's failure as a muscular pump (vide infra).

In close proximity to atrophic myocytes at sites of fibrosis are activated, α-SMA microfilament-containing myoFb expressing high-density ACE binding. The function of these myoFb and their secretory phenotype includes self-regulated expression of fibrogenic cytokine TGF-β1 and transcription of type I and III fibrillar collagens that will form scar tissue. The myoFb secretome includes angiotensin II in which this peptide regulates collagen synthesis in an autocrine manner via AT1 receptor binding and Ca2+ - mediated signaling (45, 46). This topic has recently been reviewed (55). Beyond myoFb autocrine signaling with collagen fibrillogenesis, there is the potential for heterocellular paracrine signaling. MyoFb de novo production of angiotensin II with attendant AT1 receptor binding to cardiomyocytes may account for NADPH oxidase-derived cytosolic Ca2+-mediated reactive oxygen species-driven myocyte protein turnover (56, 57). Activated AT1 receptors contribute to NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative stress and aberrant cardiomyocyte metabolism . In co-culture cardiac fibroblasts regulate cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and myocyte size and prevent re-differentiation (25, 26). An oxidative microenvironment within microdomains of fibrosis orchestrates a propensity to activate signaling cascades that modulate myocyte phenotype and behavior. The putative role of tissue angiotensin II, derived from the myoFb secretome, in paracrine regulation of oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte protein turnover will be examined in future studies. Elevations in circulating angiotensin II induce skeletal muscle protein degradation via redox-sensitive UPS ligases with consequent myocyte atrophy (58, 59).

Our second major finding relates to the molecular signaling associated with altered redox state and myocyte atrophy seen with chronic aldosteronism. We cautiously suggest small dedifferentiated myocytes ensnared by collagen fibrils are atrophied, unable to replicate, and are not cardiac stem cells. At 4 wks ALDOST small cardiomyocytes were found to express reactive oxygen species at a markedly high rate while evidence of lipid peroxidation with increased 8-isoprostane and activated redox-sensitive MuRF1 and atrogin-1 was demonstrated in cardiac tissue. Collectively, these findings suggest redox-sensitive, UPS-mediated protein degradation accounting for localized cardiomyocyte atrophy bordering on microdomains of fibrosis. An analogous pathophysiologic scenario involving UPS ligases relates to the generalized atrophy of myocardium seen in response to dexamethasone treatment and with the regression in hypertrophy that follows debanding the previously constricted aorta (15). Cardiac-specific expression of constitutively active FoxO3 transgene, the primary regulator of the UPS and autophagy/lysosomal pathway, leads to reduced heart weight and smaller cardiomyocytes, together with re-expression of β-MHC and ANP (28, 29). Contrariwise, myocyte atrophy is attenuated in MuRF1 null mice and these rodents are resistant to dexamethasone-induced cardiomyocyte atrophy (15). Their counterparts overexpressing MuRF1, on the other hand, develop a thinning of the left ventricular free wall with reduced shortening (15, 60). The functional consequences of the adverse structural and biochemical remodeling of myocardium found at 4 wks ALDOST includes delayed relaxation and stiffer ventricle with reduced E/A ratio and less efficient muscular pump with reduced fractional shortening and suspected decline in longitudinal strain.

Our third finding is the reverse remodeling and rescue of the atrophic dedifferentiated myocyte and its phenotype seen with the 4-wk regimen of assisted recovery. This included: disappearance of myoFb with myocyte re-differentiation and loss of fetal gene expression; reversal of myocyte and tissue oxidative stress with concordant improvement in diastolic and systolic function; and the return from compensatory, albeit failed, impact of NO upregulation to overcome oxidative stress. The regimen of assisted recovery with ZnSO4 and nebivolol provided a more prompt reversal toward recovery of these variables than found with natural recovery, or 4 wks ALDOST withdrawal alone (8).

Nebivolol, used as a cardioreparative strategy in our regimen of assisted recovery, enhances NO formation from endothelium-derived nitric oxide synthase and this contributes to its unique antioxidant properties (41, 42). NO donors, nitroglycerin and nitroprusside, when given via intracoronary infusion, were accompanied by an acute and marked decline in elevated left ventricular filling pressure including patients with severe aortic stenosis having concentric hypertrophy (61, 62). NO-stimulated production of cGMP (3’,5’-cyclic guanosine monophosphate) is thought responsible for this rapid improvement in diastolic distensibility (63). Nebivolol improves diastolic dysfunction in both transgenic mRen2 rats and Zucker obese rats by also reducing oxidative stress (64, 65).

Notwithstanding our major findings, this study has several limitations. We did not investigate for: the presence of connexin 43 and its potential role in heterocellular coupling, which has been reported when myoFb and myocytes are studied in co-culture (25, 66, 67); and the paracrine role of myoFb-derived de novo angiotensin II in regulating myocyte oxidative stress and protein turnover via upregulated AT1 receptors (56, 58). These issues will be explored and addressed in future studies.

In summary, the hypertensive heart disease which accompanies chronic aldosteronism features an increment in left ventricular mass, together with widely scattered foci of microscopic fibrosis. Emanating from these microdomains of fibrosis are collagen fibrils which ensnare and sequester myocytes predisposing them to disuse atrophy, and thereby disrupt the in-series alignment of myocytes and functional myofiber syncytium. Small myocytes entrapped in a microenvironment of myoFb and reactive oxygen species favors their dedifferentiation to a fetal phenotype and upregulated proteolytic UPS ligases, mechanistically linked to localized myocyte atrophy. Collectively, this pathologic remodeling of myocardium contributes to ventricular diastolic and systolic dysfunction. Assisted recovery with the antioxidants ZnSO4 and nebivolol, together with neurohormonal withdrawal, is shown to: promote myoFb disappearance from sites of fibrosis with rescue from the fetal myocyte phenotype; abrogate oxidative stress, proteolytic ligases and improve ventricular function; and restore NO. Therefore, the potential of these dedifferentiated atrophied myocytes to be rescued and revitalized with a goal toward regenerating functional myocardium offers a promising complementary strategy to ongoing efforts invested in cell-based therapies.

Acknowledgement

We wish to express our gratitude to Forest Research Institute for a research grant and study drug, and Richard A. Parkinson, MEd, for editorial assistance and scientific illustrations.

Grants

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants R01HL090867 and R01HL096813 (KTW). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Anversa P, Leri A. Innate regeneration in the aging heart: healing from within. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawn B, Bolli R. Adult bone marrow-derived cells: regenerative potential, plasticity, and tissue commitment. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100:494–503. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandya K, Kim HS, Smithies O. Fibrosis, not cell size, delineates β-myosin heavy chain reexpression during cardiac hypertrophy and normal aging in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16864–16869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607700103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandya K, Cowhig J, Brackhan J, Kim HS, Hagaman J, Rojas M, Carter CW, Jr., Mao L, Rockman HA, Maeda N, Smithies O. Discordant on/off switching of gene expression in myocytes during cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13063–13068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805120105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López JE, Myagmar BE, Swigart PM, Montgomery MD, Haynam S, Bigos M, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. β-myosin heavy chain is induced by pressure overload in a minor subpopulation of smaller mouse cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:629–638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamalov G, Zhao W, Zhao T, Sun Y, Ahokas RA, Marion TN, Al Darazi F, Gerling IC, Bhattacharya SK, Weber KT. Atrophic cardiomyocyte signaling in hypertensive heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62:497–506. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiaffino S, Samuel JL, Sassoon D, Lompré AM, Garner I, Marotte F, Buckingham M, Rappaport L, Schwartz K. Nonsynchronous accumulation of α-skeletal actin and β-myosin heavy chain mRNAs during early stages of pressure-overload--induced cardiac hypertrophy demonstrated by in situ hybridization. Circ Res. 1989;64:937–948. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheema Y, Zhao W, Zhao T, Khan MU, Green KD, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, Bhattacharya SK, Weber KT. Reverse remodeling and recovery from cachexia in rats with aldosteronism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H486–495. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00192.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell SE, Korecky B, Rakusan K. Remodeling of myocyte dimensions in hypertrophic and atrophic rat hearts. Circ Res. 1991;68:984–996. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razeghi P, Baskin KK, Sharma S, Young ME, Stepkowski S, Essop MF, Taegtmeyer H. Atrophy, hypertrophy, and hypoxemia induce transcriptional regulators of the ubiquitin proteasome system in the rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lisy O, Redfield MM, Jovanovic S, Jougasaki M, Jovanovic A, Leskinen H, Terzic A, Burnett JC., Jr. Mechanical unloading versus neurohumoral stimulation on myocardial structure and endocrine function In vivo. Circulation. 2000;102:338–343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG, Zerwekh JE, Peshock RM, Weatherall PT, Levine BD. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and spaceflight. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;91:645–653. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruber C, Nink N, Nikam S, Magdowski G, Kripp G, Voswinckel R, Mühlfeld C. Myocardial remodelling in left ventricular atrophy induced by caloric restriction. J Anat. 2012;220:179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pansani MC, Azevedo PS, Rafacho BP, Minicucci MF, Chiuso-Minicucci F, Zorzella-Pezavento SG, Marchini JS, Padovan GJ, Fernandes AA, Matsubara BB, Matsubara LS, Zornoff LA, Paiva SA. Atrophic cardiac remodeling induced by taurine deficiency in Wistar rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis MS, Rojas M, Li L, Selzman CH, Tang RH, Stansfield WE, Rodriguez JE, Glass DJ, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1 mediates cardiac atrophy in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H997–H1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00660.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaglia T, Milan G, Franzoso M, Bertaggia E, Pianca N, Piasentini E, Voltarelli VA, Chiavegato D, Brum PC, Glass DJ, Schiaffino S, Sandri M, Mongillo M. Cardiac sympathetic neurons provide trophic signal to the heart via β2-adrenoceptor-dependent regulation of proteolysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97:240–250. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wysong A, Couch M, Shadfar S, Li L, Rodriguez JE, Asher S, Yin X, Gore M, Baldwin A, Patterson C, Willis MS. NF-κB inhibition protects against tumor-induced cardiac atrophy in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearlman ES, Weber KT, Janicki JS, Pietra GG, Fishman AP. Muscle fiber orientation and connective tissue content in the hypertrophied human heart. Lab Invest. 1982;46:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huysman JAN, Vliegen HW, Van der Laarse A, Eulderink F. Changes in nonmyocyte tissue composition associated with pressure overload of hypertrophic human hearts. Pathol Res Pract. 1989;184:577–581. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(89)80162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossi MA. Pathologic fibrosis and connective tissue matrix in left ventricular hypertrophy due to chronic arterial hypertension in humans. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1031–1041. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Díez J. Mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis in hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:546–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novaes RD, Penitente AR, Gonçalves RV, Talvani A, Peluzio MC, Neves CA, Natali AJ, Maldonado IR. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces morphological reorganization of the myocardium parenchyma and stroma, and modifies the mechanical properties of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes in rats. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jalil JE, Doering CW, Janicki JS, Pick R, Shroff SG, Weber KT. Fibrillar collagen and myocardial stiffness in the intact hypertrophied rat left ventricle. Circ Res. 1989;64:1041–1050. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beltrami CA, Finato N, Rocco M, Feruglio GA, Puricelli C, Cigola E, Quaini F, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Structural basis of end-stage failure in ischemic cardiomyopathy in humans. Circulation. 1994;89:151–163. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rücker-Martin C, Pecker F, Godreau D, Hatem SN. Dedifferentiation of atrial myocytes during atrial fibrillation: role of fibroblast proliferation in vitro. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:38–52. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fredj S, Bescond J, Louault C, Potreau D. Interactions between cardiac cells enhance cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and increase fibroblast proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:891–899. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferdous A, Battiprolu PK, Ni YG, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. FoxO, autophagy, and cardiac remodeling. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9200-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schips TG, Wietelmann A, Höhn K, Schimanski S, Walther P, Braun T, Wirth T, Maier HJ. FoxO3 induces reversible cardiac atrophy and autophagy in a transgenic mouse model. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:587–597. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao DJ, Jiang N, Blagg A, Johnstone JL, Gondalia R, Oh M, Luo X, Yang KC, Shelton JM, Rothermel BA, Gillette TG, Dorn GW, Hill JA. Mechanical unloading activates FoxO3 to trigger Bnip3-dependent cardiomyocyte atrophy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter RB, Mitchell-Felton H, Essig DA, Kandarian SC. Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins during skeletal muscle disuse atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1285–1290. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min K, Smuder AJ, Kwon OS, Kavazis AN, Szeto HH, Powers SK. Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants protect skeletal muscle against immobilization-induced muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1459–1466. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00591.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellegrino MA, Desaphy JF, Brocca L, Pierno S, Camerino DC, Bottinelli R. Redox homeostasis, oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Physiol. 2011;589:2147–2160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.203232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rota M, Padin-Iruegas ME, Misao Y, De Angelis A, Maestroni S, Ferreira-Martins J, Fiumana E, Rastaldo R, Arcarese ML, Mitchell TS, Boni A, Bolli R, Urbanek K, Hosoda T, Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J. Local activation or implantation of cardiac progenitor cells rescues scarred infarcted myocardium improving cardiac function. Circ Res. 2008;103:107–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamalov G, Ahokas RA, Zhao W, Johnson PL, Shahbaz AU, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Temporal responses to intrinsically coupled calcium and zinc dyshomeostasis in cardiac myocytes and mitochondria during aldosteronism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H385–H394. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00593.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahbaz AU, Kamalov G, Zhao W, Zhao T, Johnson PL, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Mitochondria-targeted cardioprotection in aldosteronism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:37–43. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181fe1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawyer DB. Oxidative stress in heart failure: what are we missing? Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:120–124. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182249fcd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gladden JD, Ahmed MI, Litovsky SH, Schiros CG, Lloyd SG, Gupta H, Denney TS, Jr., Darley-Usmar V, McGiffin DC, Dell'Italia LJ. Oxidative stress and myocardial remodeling in chronic mitral regurgitation. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:114–119. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318224ab93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chhokar VS, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Myers LK, Xing Z, Smith RA, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Hyperparathyroidism and the calcium paradox of aldosteronism. Circulation. 2005;111:871–878. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155621.10213.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidal A, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Calcium paradox of aldosteronism and the role of the parathyroid glands. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H286–H294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00535.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamalov G, Ahokas RA, Zhao W, Zhao T, Shahbaz AU, Johnson PL, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Uncoupling the coupled calcium and zinc dyshomeostasis in cardiac myocytes and mitochondria seen in aldosteronism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;55:248–254. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181cf0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheema Y, Sherrod JN, Zhao W, Zhao T, Ahokas RA, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Bhattacharya SK, Weber KT. Mitochondriocentric pathway to cardiomyocyte necrosis in aldosteronism: cardioprotective responses to carvedilol and nebivolol. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:80–86. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821cd83c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan MU, Zhao W, Zhao T, Al Darazi F, Ahokas RA, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Nebivolol: a multifaceted antioxidant and cardioprotectant in hypertensive heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62:445–451. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182a0b5ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Y, Zhang J, Lu L, Chen SS, Quinn MT, Weber KT. Aldosterone-induced inflammation in the rat heart. Role of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1773–1781. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada H, Fabris B, Allen AM, Jackson B, Johnston CI, Mendelsohn FAO. Localization of angiotensin converting enzyme in rat heart. Circ Res. 1991;68:141–149. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramires FJA, Sun Y, Weber KT. Myocardial fibrosis associated with aldosterone or angiotensin II administration: attenuation by calcium channel blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:475–483. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Y, Zhang J, Lu L, Bedigian MP, Robinson AD, Weber KT. Tissue angiotensin II in the regulation of inflammatory and fibrogenic components of repair in the rat heart. J Lab Clin Med. 2004;143:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamalov G, Deshmukh PA, Baburyan NY, Gandhi MS, Johnson PL, Ahokas RA, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Coupled calcium and zinc dyshomeostasis and oxidative stress in cardiac myocytes and mitochondria of rats with chronic aldosteronism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;53:414–423. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181a15e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luss H, Watkins SC, Freeswick PD, Imro AK, Nussler AK, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, del Nido PJ, McGowan FX., Jr. Characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in endotoxemic rat cardiac myocytes in vivo and following cytokine exposure in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:2015–2029. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geisler SB, Green KJ, Isom LL, Meshinchi S, Martens JR, Delmar M, Russell MW. Ordered assembly of the adhesive and electrochemical connections within newly formed intercalated disks in primary cultures of adult rat cardiomyocytes. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:624719. doi: 10.1155/2010/624719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Razeghi P, Young ME, Alcorn JL, Moravec CS, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Metabolic gene expression in fetal and failing human heart. Circulation. 2001;104:2923–2931. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.100526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swynghedauw B. Molecular Cardiology for the Cardiologist. Kluwer; Boston: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardner DG, Deschepper CF, Ganong WF, Hane S, Fiddes J, Baxter JD, Lewicki J. Extra-atrial expression of the gene for atrial natriuretic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:6697–6701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vikstrom KL, Bohlmeyer T, Factor SM, Leinwand LA. Hypertrophy, pathology, and molecular markers of cardiac pathogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;82:773–778. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.7.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Konno T, Chen D, Wang L, Wakimoto H, Teekakirikul P, Nayor M, Kawana M, Eminaga S, Gorham JM, Pandya K, Smithies O, Naya FJ, Olson EN, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Heterogeneous myocyte enhancer factor-2 (Mef2) activation in myocytes predicts focal scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18097–18102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012826107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weber KT, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC. Myofibroblast-mediated mechanisms of pathological remodelling of the heart. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:15–26. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leri A, Liu Y, Li B, Fiordaliso F, Malhotra A, Latini R, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Up-regulation of AT1 and AT2 receptors in postinfarcted hypertrophied myocytes and stretch-mediated apoptotic cell death. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1663–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65037-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gul R, Shawl AI, Kim SH, Kim UH. Cooperative interaction between reactive oxygen species and Ca2+ signals contributes to angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H901–909. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00250.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sukhanov S, Semprun-Prieto L, Yoshida T, Michael Tabony A, Higashi Y, Galvez S, Delafontaine P. Angiotensin II, oxidative stress and skeletal muscle wasting. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:143–147. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318222e620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cabello-Verrugio C, Córdova G, Salas JD. Angiotensin II: role in skeletal muscle atrophy. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2012;13:560–569. doi: 10.2174/138920312803582933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willis MS, Schisler JC, Li L, Rodríguez JE, Hilliard EG, Charles PC, Patterson C. Cardiac muscle ring finger-1 increases susceptibility to heart failure in vivo. Circ Res. 2009;105:80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matter CM, Mandinov L, Kaufmann PA, Vassalli G, Jiang Z, Hess OM. Effect of NO donors on LV diastolic function in patients with severe pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation. 1999;99:2396–2401. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulus WJ, Vantrimpont PJ, Shah AM. Acute effects of nitric oxide on left ventricular relaxation and diastolic distensibility in humans. Assessment by bicoronary sodium nitroprusside infusion. Circulation. 1994;89:2070–2078. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hare JM, Colucci WS. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of myocardial function. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995;38:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(05)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma L, Gul R, Habibi J, Yang M, Pulakat L, Whaley-Connell A, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR. Nebivolol improves diastolic dysfunction and myocardial remodeling through reductions in oxidative stress in the transgenic (mRen2) rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2341–2351. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01126.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou X, Ma L, Habibi J, Whaley-Connell A, Hayden MR, Tilmon RD, Brown AN, Kim JA, Demarco VG, Sowers JR. Nebivolol improves diastolic dysfunction and myocardial remodeling through reductions in oxidative stress in the Zucker obese rat. Hypertension. 2010;55:880–888. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chilton L, Giles WR, Smith GL. Evidence of intercellular coupling between co-cultured adult rabbit ventricular myocytes and myofibroblasts. J Physiol. 2007;583:225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thompson SA, Copeland CR, Reich DH, Tung L. Mechanical coupling between myofibroblasts and cardiomyocytes slows electric conduction in fibrotic cell monolayers. Circulation. 2011;123:2083–2093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]