Abstract

Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen responsible for hospital-acquired infections. Most C albicans infections are associated with the implantation of medical devices that act as points of entry for the pathogen and as substrates for the growth of fungal biofilms that are notoriously difficult to eliminate by systemic administration of conventional antifungal agents. In this study, we report a fill-and-purge approach to the layer-by-layer fabrication of biocompatible, nanoscale ‘polyelectrolyte multilayers’ (PEMs) on the luminal surfaces of flexible catheters, and an investigation of this platform for the localized, intraluminal release of a cationic β-peptide-based antifungal agent. We demonstrate that polyethylene catheter tubes with luminal surfaces coated with multilayers ~700 nm thick fabricated from poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA) and poly-L-lysine (PLL) can be loaded, post-fabrication, by infusion with β-peptide, and that this approach promotes extended intraluminal release of this agent (over ~4 months) when incubated in physiological media. The β-peptide remained potent against intraluminal inoculation of the catheters with C albicans and substantially reduced the formation of C albicans biofilms on the inner surfaces of film-coated catheters. Finally, we report that these β-peptide-loaded coatings exhibit antifungal activity under conditions that simulate intermittent catheter use and microbial challenge for at least three weeks. We conclude that β-peptide-loaded PEMs offer a novel and promising approach to kill C albicans and prevent fungal biofilm formation on surfaces, with the potential to substantially reduce the incidence of device-associated infections in indwelling catheters. β-Peptides comprise a promising new class of antifungal agents that could help address problems associated with the use of conventional antifungal agents. The versatility of the layer-by-layer approach used here thus suggests additional opportunities to exploit these new agents in other biomedical and personal care applications in which fungal infections are endemic.

Keywords: Antifungal, Biofilms, Catheters, Controlled Release, Polymer Multilayers, Surfaces

Introduction

Candida albicans is the pathogen most responsible for hospital-acquired fungal infections in humans.1 This opportunistic pathogen causes systemic and often fatal infections, especially in immunocompromised patients including those afflicted with AIDS, undergoing chemotherapy, or receiving organ transplants.2–4 It is estimated that about 400,000 cases of candidemia (the presence of C. albicans in the bloodstream) occur annually, and the mortality rate associated with this condition ranges from 30 to 60%.3–5 Apart from the human suffering this causes, the annual economic burden of fungal infections is in the billions of dollars in the U.S. alone.6

It has been estimated that over half of all hospital-acquired infections are associated with the insertion of a medical device.7,8 Indwelling medical devices, and catheters in particular, are major risk factors for systemic C. albicans infections4,7,9 because they act as both a point of entry for the pathogen and a substrate for the subsequent growth of fungal biofilms10,11 that exhibit resistance to antifungal drugs and provide protection against host defenses.8,12–14 Current methods for the prevention and treatment of catheter-associated C. albicans infections involve periodic replacement of catheters combined with treatments using systemically-administered antifungal drugs.9,15 These measures are far from optimal because catheter removal may require surgery and replacement is both expensive and can cause discomfort or other complications.16–18 Moreover, the indiscriminate use of systemic antifungal drugs can facilitate the development of evolved resistance.8,19 In view of these and other practical and clinical considerations, there is a critical need for the development of both new antifungal agents and new strategies to deliver these agents to sites either experiencing or at high risk for device-associated fungal infections. The work reported here was motivated by these two important challenges.

Most conventional antifungal agents used to combat candidemia act by inhibiting specific enzymes or cell wall or membrane components in C. albicans. As noted above, this pathogen can, and in some cases has, evolved mechanisms of resistance than can render agents that act through these mechanisms ineffective.8,20,21 Additionally, several existing antifungal drugs (including amphotericin B, the current gold standard for the clinical treatment of C. albicans infections) are not particularly selective toward fungi and, thus, also exhibit high levels of toxicity in human cells (e.g., nephrotoxicity in the case of amphotericin B).22,23 Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and their analogues derived from or modeled upon components of the innate and adaptive immune systems of various host organisms have also been investigated broadly as antimicrobial agents, in part because these agents achieve their potency through membrane-disrupting processes that are less likely to lead to evolved resistance.24–27 Unfortunately, while AMPs are promising in this latter context, these peptide-based agents often exhibit low stabilities and activities in physiological environments, such as in the presence of proteases or at physiologic ionic strength.25,27 To address these two issues and advance the design of AMPs that are active and selective against fungal pathogens, our groups and others have designed new AMP structures based on more stable β-peptide scaffolds that mimic many of the important structural features of antimicrobial α-peptides.28–32 Of particular relevance to the work reported here, we have demonstrated that 14-helical β-peptides can be designed to kill C. albicans efficiently and selectively (e.g., at concentrations that exhibit low toxicity to human red blood cells).28,29 These antifungal β-peptide structures can also inhibit the formation of fungal biofilms when administered in bulk solution to populations of planktonic C. albicans or when released slowly from polymer coatings containing embedded β-peptide.28,29,33

In this study, we developed an approach to localize the delivery of antifungal β-peptides from the surfaces of indwelling medical devices; such approaches have the potential to prevent device-associated infection more effectively, and with fewer patient side effects, than approaches based on systemic drug administration. Past studies on surface-based strategies for the prevention or treatment of device-associated microbial infections generally fall into one of two broad categories: (i) the design of surfaces that either prevent microbial adhesion or kill adherent microbes on contact, or (ii) the design of surfaces that passively release agents that possess antimicrobial properties (controlled release approaches).34–41 Examples of release-based approaches include coatings and surface treatments that slowly elute metal ions such as silver or copper,42–44 antibiotics and antiseptics,45–47 antimicrobial compounds,48–50 nitric oxide,51,52 or inhibitors of bacterial quorum sensing.53,54 The majority of past studies in this area have focused on the inhibition of bacterial biofilms;35,39,40,42,47,48,54 studies on the localized, surface-mediated release of agents that prevent fungal biofilm growth are fewer and more recent.33,48,50

Here, we report new approaches to the post-fabrication loading and sustained release of a potent antifungal β-peptide from thin “polyelectrolyte multilayer” (PEM) films55–58 fabricated on the inner surfaces of flexible catheter tubes. We demonstrate that incorporated β-peptide remains potent against planktonic C. albicans upon both short- and long-term incubation, and that these methods prevent or substantially reduce the formation of C. albicans biofilms on the inner surfaces of film-coated catheter tubes in in vitro assays. Finally, we show that these coatings remain potent and exhibit antifungal activity under conditions that simulate intermittent catheter use and microbial challenge for at least three weeks. Overall, our results suggest that β-peptide-loaded PEMs offer a novel and useful approach to kill C. albicans and prevent fungal biofilm formation on surfaces, with the potential to help prevent device-associated infections in indwelling catheters. The versatility of this approach also suggests potential utility in a range of other biomedical and personal care applications in which fungal infections are problematic.

Materials and Methods

General Considerations

Measurements of the fluorescence of solutions used to characterize the release of fluorescently labeled β-peptide from multilayered films were made using a NanoDrop3300 (Thermo Scientific). Fluorescence microscopy was performed using an Olympus IX71 microscope and images were obtained using the MetaMorph Advanced version 7.7.8.0 software package (Universal Imaging Corporation). Images were processed using NIH Image J software and Microsoft Powerpoint 2010. In all catheter tube-based experiments where the ends of the tubes were reversibly sealed, this was performed by plugging the ends of the tube with custom made metal stoppers. C. albicans colonies on agar plates were counted manually. Coumarin-linker-(ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide was synthesized by solid phase synthesis in a CEM discover microwave reactor using methods reported previously.28,33 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a LEO SEM microscope. Critical point drying of SEM samples was performed in Critical Point Dryer (Tousimis Samdri-815). Absorbance measurements used in XTT assays were acquired at 490 nm using a plate reader (EL800 Universal Microplate Reader, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc). Sonication of tubes for biofilm inhibition assays was performed using a sonication bath (Branson 2510R-MT).

Materials

Polyethylene tubing (PE-100 [inner diameter, 0.034 in.]) was purchased from Intramedic, Becton Dickinson and Company. Poly-L-lysine hydrobromide (PLL, MW = 15,000–30,000), poly-L-lysine-FITC labeled (FITC-PLL, MW = 15,000–30,000), poly-L-glutamic acid sodium salt (PGA, MW = 50,000–100,000), and polyethylenimine, branched (BPEI, MW = 25,000) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All polyelectrolytes were used as received without any further purification. RPMI 1640 powder (with L-glutamine and phenol red, without HEPES and sodium bicarbonate) and 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) were purchased from Invitrogen. 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), Tris-base, and NaCl were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) liquid concentrate (10×) was purchased from OmniPur. Menadione, glutaraldehyde, and formaldehyde were purchased from Sigma. Tween-20 was purchased from Acros. Osmium tetroxide (4%) was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences.

Fabrication of Multilayered Films

Solutions of BPEI, PLL, and PGA used for the fabrication of multilayered films were prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL using a NaCl (0.15 M) solution in deionized water. All films were deposited on the inner surfaces of polyethylene catheter tubes pre-coated with a single layer of BPEI by infusing a solution of BPEI into the tube and allowing it to incubate in the tube for 10 min. The tubes were then rinsed by infusing a solution of NaCl (0.15 M) in water into the tube for 1 min followed by a second rinse for 1 min. PEM films were then deposited using a ‘fill-and-purge’ approach and the following general method: (i) a solution of PGA was infused into the tube and allowed to incubate for 3 min, (ii) tubes were rinsed by infusing a rinse solution of NaCl solution in water (0.15 M) for 1 min followed by a second rinse for 1 min, (iii) tubes were infused with a solution of PLL for 3 min, and (iv) tubes were rinsed again in the manner described in step (ii). This cycle was repeated until the desired number of PGA/PLL bilayers (typically 19.5) had been deposited. Films fabricated in this manner are denoted using the notation (PGA/PLL)x, where x is the number of ‘bilayers’ (or PGA/PLL layer pairs) deposited. For experiments designed to characterize film growth, PEMs consisting of PGA/FITC-PLL were fabricated using the general procedure described above. Film growth was monitored using fluorescence microscopy to characterize fluorescence at intermittent stages during layer-by-layer fabrication (see text).

Post-Fabrication Loading of β-Peptide in Film-Coated Catheters

Tubes with inner surfaces coated with PGA/PLL multilayers were infused with a 10 mg/mL solution of coumarin-linker-(ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 in 0.15 M NaCl and the peptide solution was allowed to incubate in the tubes for 24 hours at room temperature. The ends of the tube were reversibly sealed during this procedure to prevent any leakage or evaporation of the peptide solution during incubation. After 24 hours, the peptide solution was removed from the tubes and the tubes were rinsed in the following manner: (i) a solution of PBS was infused into the tubes and allowed to incubate for 5 min, (ii) a solution of Tris-buffered saline Tween (TBST; 10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 % Tween-20) was incubated in the tube for 1 hour, and (iii) a PBS rinse was performed in the manner described in step (i). Tubes fabricated using this procedure were either used immediately or stored in a dried state at room temperature until use. Bare, uncoated tubes to be used as controls were treated with peptide in the manner described above. Film-coated tubes to be used as no-peptide controls were fabricated in the manner described in the previous section but were not loaded with peptide. For SEM studies, an additional control consisting of film-coated tubes incubated with buffer prior to analysis was treated as described above, with the exception that buffer free of β-peptide was used in place of the peptide incubation step.

Characterization of Intraluminal β-peptide Release Profiles

Experiments designed to characterize the release of incorporated β-peptide into the luminal spaces of film-coated catheter tubes were performed in the following manner. PBS solution (10 μL) was infused to completely fill a segment (2 cm in length) of β-peptide-treated tubes, the ends of the tubes were reversibly sealed, and the filled tubes were incubated at 37 °C. The tubes were removed from the incubator at predetermined intervals for characterization of solution fluorescence at an excitation of 336 nm and an emission of 402 nm, corresponding to the excitation and emission maxima of the coumarin label on the β-peptide. Fluorescence measurements resulting from these experiments were converted to β-peptide concentrations using a calibration curve generated using known concentrations of β-peptide. After each measurement, the tubes were infused with an aliquot of fresh PBS and returned to the incubator. The plot shown in Figure 3E was made by cumulatively adding the concentration of β-peptide released into solution at each of the time points.

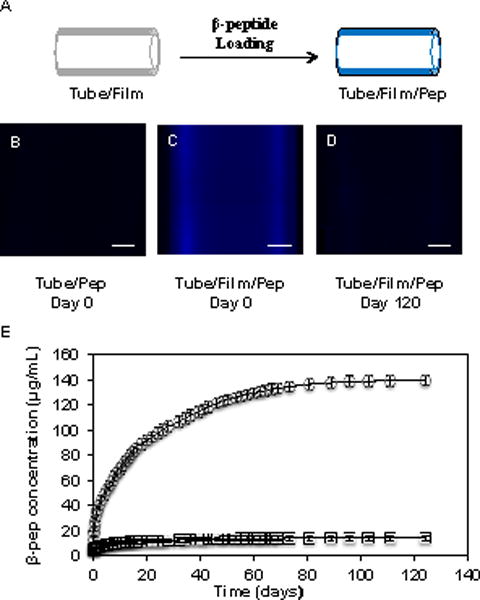

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic illustration depicting the post-fabrication loading of film-coated catheter tubes with β-peptide. (B–D) Representative fluorescence micrographs of (B) an uncoated catheter and (C) a catheter coated with a PGA/PLL film 19.5 bilayers thick after incubation in a solution of β-peptide for 24 hours. (D) Fluorescence micrograph of a film-coated, β-peptide-loaded catheter after incubation in PBS for 120 days; scale bars = 250 μm. (E) Plot showing the release of β-peptide into the lumen of a film-coated, β-peptide-loaded catheter (circles) and a no-film control catheter incubated with β-peptide (squares) incubated in PBS at 37 °C. Data points are the average of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviation.

Characterization of Antifungal Activity

C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown overnight at 30 °C in liquid yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium. Cells were washed with PBS and re-suspended in RPMI 1640 medium buffered with MOPS (pH 7.0). The cell density was adjusted to 106 cfu/mL with RPMI 1640. Catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films (and catheters used as no-peptide, and no-film/no-peptide controls) were cut into 3 cm segments, 15 μL of C. albicans cell suspensions were infused into the tubes to fill the tube segment entirely, the ends of the tubes were reversibly sealed as described above, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C. Tubes were removed from the incubator 6 hours post-incubation. The C. albicans inoculum was removed from the tubes and a 100-fold dilution of the inoculum was plated on YPD plates. The YPD plates were incubated at 37 °C for ~ 24 hours and the number of colonies formed was then counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated on at least three different days. To evaluate antifungal activity of the tubes at later times (see text), segments of the catheters were pre-incubated with PBS at 37 °C for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 16, or 21 days, after which antifungal activity was evaluated by performing experiments as described above. At the end of the 6-hour C. albicans inoculum incubation, solutions were placed in individual wells of a 96-well plate and, 24 hours later, an XTT assay was performed to assess the number of metabolically active cells in the inoculum removed from the tubes. Background absorbance from wells containing media and XTT was subtracted from all readings and data was plotted relative to the absorbance value from wells containing samples of solution from no-film/no-peptide control tubes.

Biofilm Inhibition Assays

C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown overnight at 30 °C in liquid YPD medium. Cells were washed with PBS and re-suspended in RPMI 1640 medium buffered with MOPS (pH 7.0) and supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (RPMI + 5 % FBS) to stimulate biofilm formation. The cell density was adjusted to 106 cfu/mL with RPMI + 5 % FBS. 15 μL of a C. albicans cell suspension was then infused into 3 cm segments of catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films (and catheters used as no-peptide and no-film/no-peptide controls) and the tubes were placed in separate wells of a 6-well plate containing 2 mL of RPMI + 5 % FBS per well. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours. After 48 hours, biofilm growth in the tubes was characterized using either (i) a metabolic XTT assay or (ii) by visualizing the biofilm formed by SEM.

For the metabolic XTT assay, each tube was placed in an individual microcentrifuge tube and sonicated for 15 min to dislodge any strongly adherent biofilm. The inoculum was then removed from inside the tubes and placed in separate wells of a 96 well plate. The tubes were washed twice with PBS (40 μL per wash) and the wash solutions were added to respective wells of the 96 well plate. The microcentrifuge tubes were centrifuged and the recovered solution was also added to respective wells of the 96 well plate. XTT solution (40 μL; 0.5g/L in PBS, pH 7.4, containing 3 µM menadione in acetone) was added to each well containing biofilm solution and to wells containing only RPMI + 5 % FBS to serve as negative controls. After incubating the solution at 37 °C for 2 h, 75 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the absorbance of the solution at 490 nm was measured to determine the relative metabolic activity of biofilms formed in the different tubes. Background absorbance from wells containing media and XTT was subtracted from all readings and data was plotted relative to the absorbance value from wells containing samples of solution from no-film/no-peptide control tubes.

For analysis by SEM, catheter tube segments were placed in fixative [1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (v/v) formaldehyde] overnight at 4 °C. The samples were rinsed in PBS (0.1 M) for 10 min and then placed in osmium tetroxide (1%) for 30 min, followed by 10 min in phosphate buffer (0.1 M). The samples were subsequently dehydrated in a series of ethanol washes (30%, 50%, 70%, 85%, 95% and 100% for 10 min each). Final desiccation was accomplished by critical-point drying. Specimens were mounted on aluminum stubs and sliced open to reveal the inside of the catheter, then sputter coated with gold-palladium. Samples were characterized by SEM in high-vacuum mode at 5 kV.

Results and Discussion

We investigated the release of antifungal β-peptides from thin PEMs fabricated using PGA and PLL in this study because PGA/PLL multilayers have been used in past studies as a biocompatible platform for the release of a wide variety of active agents, including antibacterial and antifungal AMPs, both in vitro and in vivo49,50,59 We demonstrated recently that cationic β-peptides could be incorporated into PGA/PLL multilayers using conventional dipping-based processes to deposit them directly (e.g., as multiple ‘layers’) during each iterative cycle of the PEM fabrication process.33 The results of that study also demonstrated that β-peptide-loaded films fabricated on model planar substrates (e.g., glass slides) could be used to kill planktonic C. albicans in vitro. While the results of that proof-of-concept study were promising, dipping-based approaches to layer-by-layer assembly are not well suited for the selective deposition of coatings on the inner surfaces of small-gauge tubing, including the insides of catheter tubes, and the resulting films released β-peptide over relatively short times (~17 days) in physiological media. In this current study, we sought to (i) develop practical approaches to the fabrication of PGA/PLL multilayers on the inner surfaces of flexible, microscale catheter tubes, and (ii) develop approaches to post-fabrication loading that permit the sustained and extended release of β-peptide into the lumen of a catheter to (iii) kill planktonic C. albicans and (iv) prevent or reduce the formation of fungal biofilms.

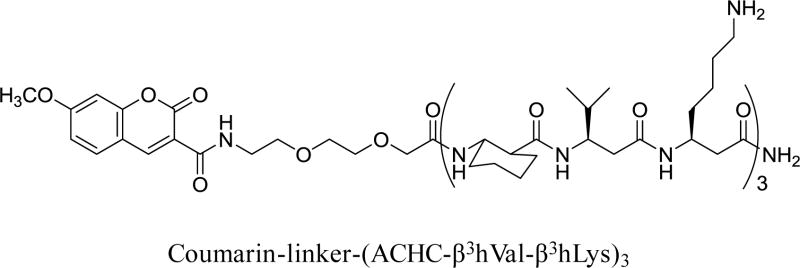

The antifungal β-peptide used in all of the experiments described here is shown in Scheme 1. This 14-helical β-peptide has a charge of +3, adopts a globally helical amphiphilic conformation, and has been demonstrated to exhibit high antifungal activity against C. albicans (MIC = 8 μg/mL, Figure S1) as well as selectivity (e.g., low hemolytic activity) at MIC.28 This β-peptide contains a fluorescent coumarin label attached at the N-terminus to facilitate detection and quantification of the peptide on surfaces and in solution. The addition of this fluorescent probe does not significantly alter antifungal activity toward C. albicans or hemolytic activity relative to that of unlabeled analogs.28

Scheme 1.

Structure of the coumarin-labeled, 14-helical β-peptide used in this study.

Fabrication of PEMs on the Inner Surfaces of Catheter Tubes: A Fill-and-Purge Approach

PGA/PLL multilayers were fabricated on the inner surfaces of polyethylene catheter tubes (~860 μm in diameter) using a ‘fill-and-purge’ approach by iteratively filling each tube with solutions of PGA or PLL manually via pipette (e.g., see Figure 1A). Each treatment with PGA or PLL was followed by purging the catheter with polymer-free wash buffer to flush out remaining polymer solution and remove loosely bound polymer (see Materials and Methods for additional details). For all experiments reported below, this iterative process was repeated 19.5 times to produce multilayer coatings having the nominal structure (PGA/PLL)19(PGA).

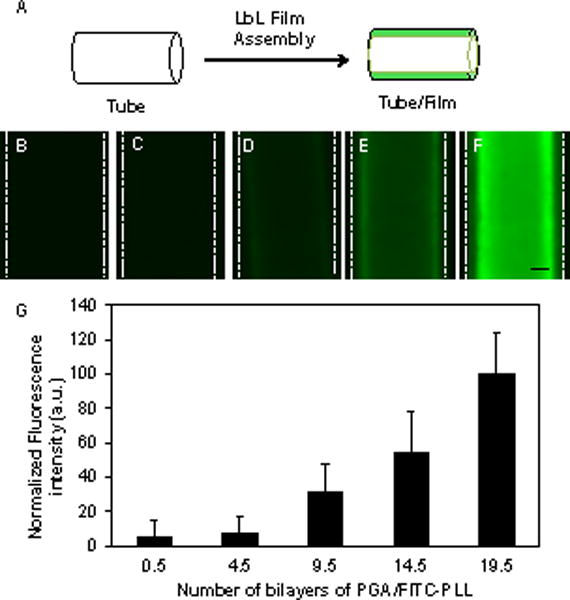

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration depicting fabrication of PEM films on the luminal surfaces of polyethylene catheter tubes. (B–F) Representative fluorescence micrographs of catheters coated with (PGA/FITC-PLL)x PEMs with increasing bilayers; x = 0.5 (B), 4.5 (C), 9.5 (D), 14.5 (E), and 19.5 (F). Scale bar = 250 μm. (G) Plot of the average fluorescence intensity as a function of the number of bilayers of PGA/PLL deposited. Data points are the average of measurements in three regions of two independent experiments, normalized to the fluorescence intensity of (PGA/FITC-PLL)19.5 films; error bars represent standard deviation.

Past studies have established that PGA/PLL-based multilayers increase in thickness in a supra-linear manner when fabricated using conventional dipping-based fabrication procedures.60,61 The dimensions and confined geometry of the tubing used here prevented characterization of layer-by-layer film growth using methods such as ellipsometry or QCM reported in past studies. To characterize the growth of PEMs on the inner surfaces of the tubes, we fabricated films using fluorescently labeled PLL and monitored the fluorescence intensity of the films on the tubing using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis after the deposition of every five PGA/PLL bilayers. The fluorescence intensity of the films increased as the number of bilayers deposited increased (Figure 1B–F). A plot of average fluorescence intensity as a function of the number of bilayers deposited is also shown in Figure 1G. When combined, these results demonstrate that PEMs can be deposited uniformly on the inner surfaces of these catheters and that the fill-and-purge fabrication protocol used here also leads to supra-linear film growth observed previously in PGA/PLL PEMs using conventional dipping-based methods on planar substrates.33,59,61

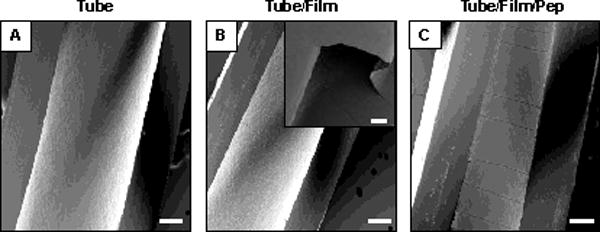

Characterization of the inner surfaces of longitudinally-sliced, film-coated catheters by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed the presence of uniform and relatively defect-free films that did not crack, peel, or delaminate substantially from the underlying substrate in response to manual bending or physical forces associated with handling and cutting the catheter tubes (Figure 2A–B). On the basis of additional SEM characterization of cross-sections of these films (Figure S2A), we estimate the average thicknesses of the 19.5-bilayer PGA/PLL films fabricated using this fill-and-purge approach to be 711 ± 45 nm.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy images of longitudinally-sliced catheter tubes: (A) bare tube (no film/no peptide), (B) a tube coated with a PGA/PLL film 19.5 bilayers thick, (C) a film with a PGA/PLL 19.5 bilayers thick post-loaded with β-peptide; scale bars = 200 μm. The inset in (B) shows a region where a portion of the sliced films lifted off the surface of the tube, which was useful in measuring the cross sectional thicknesses of the films (see text and Figure S2). Inset scale bar = 25 μm.

Post-Fabrication Loading and Release of β-Peptide from Film-Coated Catheters

We loaded catheters coated with PGA/PLL multilayers with antifungal β-peptide by filling film-coated catheters with aqueous solutions of β-peptide and allowing the peptide to diffuse into the film (Figure 3A). This post-loading approach permits control over the amount of β-peptide loaded into the film by control over the time that a film is exposed to the β-peptide, and differs from past approaches that incorporated β-peptide directly into a film (e.g., as multiple ‘layers’) during layer-by-layer assembly.33 Characterization of film-coated tubes after infusion of a β-peptide solution for 24 hours (followed by washing with a surfactant solution to remove surface-bound β-peptide) by fluorescence microscopy revealed β-peptide to be distributed uniformly across the tube surface (Figure 3C). Figure 3B also shows an image of a bare control catheter that was incubated with coumarin-labeled β-peptide. Taken together, these images demonstrate that the multilayer film enhances localization of the peptide on the inner surface of the catheter.

Characterization of β-peptide-loaded films by SEM (Figure S2C) revealed the average thickness to be 993 ± 49 nm, significantly higher (p < 0.0001) than the average thickness of these films prior to loading (~711 ± 45 nm). The average thickness of control films incubated in otherwise identical buffer lacking β-peptide was measured to be 690 ± 22 nm (Figure S2B), a value that is similar (p < 0.001) to that of the as-fabricated films prior to loading. These results demonstrate that exposure to β-peptide induced a substantial increase in film thickness, and are consistent with the absorption and infiltration of β-peptide into the multilayers rather than simple adsorption of a monolayer of this cationic peptide on the surface of the films. The results of additional β-peptide release experiments described below provide additional support for this proposition. Figure 2C shows a top-down SEM image of a β-peptide-loaded film. The straight-line cracking evident in this image is representative but was not observed in all samples; our experience suggests that these defects are likely related to processes associated with the preparation of these peptide-loaded films for SEM analysis rather than morphological changes that arise during fabrication or physical manipulation during film loading.

Many past studies demonstrate that PGA/PLL multilayers do not dissolve or erode substantially when incubated in physiologically relevant media, but that embedded small molecules can diffuse out passively at rates that are controlled by the size and charge of the agent, the thickness of the films, and many other factors.33,49,50,59,62,63 To characterize the impact of post-loading procedures on the intraluminal release profiles of our film-coated catheters, segments of β-peptide-loaded, film-coated tubes were filled with PBS and incubated at 37 °C. Figure 3E shows a representative release profile for β-peptide-loaded catheters, characterized by fluorometry, along with the release profile of bare control catheters soaked in a solution of β-peptide as described above. Inspection of these data reveals that β-peptide was released gradually from the film-coated catheters over a period of 120 days (~4 months). By the end of this period, the films had released ~1.6 μg of β-peptide, and characterization of film-coated catheters by fluorescence microscopy revealed negligible levels of remaining coumarin-associated fluorescence in the PEM films by visual inspection (Fig 2D). On the basis of these results and the dimensions of the catheters used here, we calculate the loading of β-peptide to be ~3 μg/cm2.

The 120-day β-peptide release profile shown in Figure 3E is substantially longer than the ~17 day release profile reported in a past study in which this same coumarin-labeled β-peptide was incorporated into PGA/PLL multilayers directly during layer-by-layer assembly.33 Both of these release profiles could be useful in the context of indwelling catheters, where larger initial doses followed by slower, sustained release could help eliminate microorganisms introduced during implantation and then subsequently prevent longer-term colonization. We note, however, that the loading of the films in that past study, in which β-peptide was incorporated iteratively during each step of film fabrication rather than infused into the films after assembly, was also substantially higher (e.g., ~83 ug/cm2 versus ~3 ug/cm2) than of the films designed in this current study. We did not attempt to identify the maximum loading of β-peptide that can be achieved using our current post-loading approach, but it is likely that loading can be increased substantially by modifying the conditions used to infuse the films or by using thicker films. In view of the dimensions of the catheters used here, we note that a loading of ~3 μg/cm2 is sufficient to generate an intraluminal β-peptide concentration ~17 times the MIC of this agent, and this loading was sufficient to inhibit C. albicans growth and biofilm formation in subsequent in vitro experiments. In addition, this post-loading approach permits the fabrication of β-peptide-loaded coatings using substantially smaller volumes of β-peptide solution and requires fewer overall fabrication steps than would be required if β-peptide were deposited during each iterative cycle of the fill-and-purge fabrication protocol used here. Finally, we mention that the β-peptide release studies reported in Figure 3E were performed using film-coated catheters filled with PBS buffer, and that while PGA/PLL films are stable in PBS, rates of release of β-peptide could vary significantly in the presence of more complex media. We return to a discussion of this possibility again in the sections below.

Antifungal Activity of Catheters Coated with β-Peptide-Loaded Films

The results above reveal that catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films released >20 μg of peptide per mL of catheter lumen volume during the first 6 hours of incubation in PBS, resulting in an intraluminal concentration 2.5 times the MIC of this agent (8 μg/mL, Figure S1). To evaluate the antifungal activities of catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films at short times after inoculation, we incubated a suspension of C albicans (106 cfu/mL) inside tube segments for 6 hours. After 6 hours, the yeast solutions were removed from the tubes, plated on agar, and then colonies were counted after 24 hours. We observed striking differences in the number of viable cells drawn from catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films as compared to controls. Whereas inocula drawn from bare tubes (no-film/no-peptide controls) and from film-coated tubes that did not contain β-peptide (no-peptide controls) resulted in numerous C albicans colonies, inocula drawn from tubes coated with β-peptide-loaded films contained virtually no viable C albicans cells, as indicated by the lack of colonies on agar plates (Figure S3). Quantitative characterization of this reduction in cells, shown in Figure 4, revealed an ~10,000-fold reduction in number of viable C albicans cells in samples incubated in catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films. We conclude from these results that released β-peptide remained potent against planktonic C albicans over short periods following inoculation.

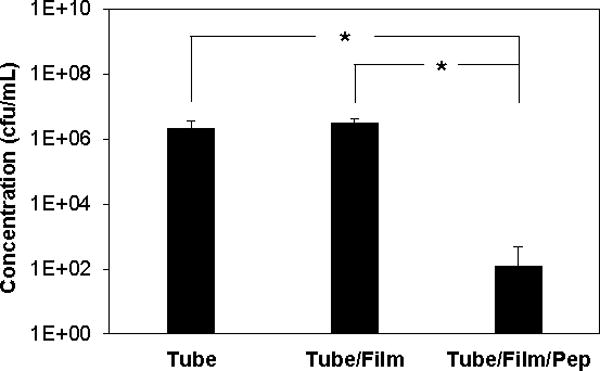

Figure 4.

Antifungal activity of untreated catheters (tube), catheters coated with PGA/PLL films (tube/film), and catheters coated with PGA/PLL films and loaded with β-peptide (tube/film/pep). C. albicans inoculum (106 cfu/mL) was incubated in the tubes for 6 hours at 37 °C. 100-Fold dilutions of the inocula from tubes were plated on solid YPD and colonies were counted after 24 hours. Data points are averages of measurements from three independent experiments of three replicates each and error bars denote standard deviation; (* indicates p < 0.005 by a two-tailed T-test).

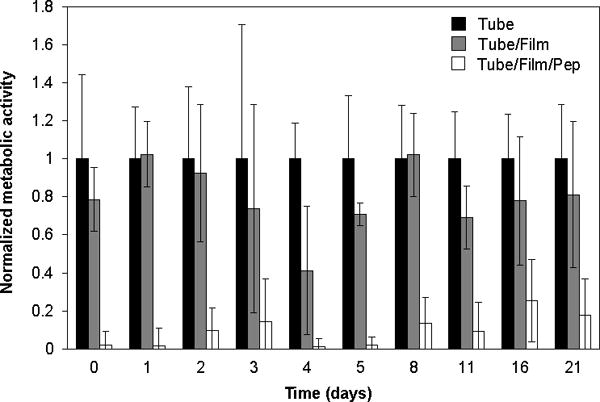

A series of additional experiments demonstrated that catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films retained substantial antifungal activity when incubated in physiologically relevant media for up to three weeks. These longer-term experiments were designed to approximate conditions wherein a catheter would experience a C albicans challenge at some point after implantation and after the initial release and elimination of substantial amounts of β-peptide (e.g., as would occur upon periodic infusion of fluid to a previously installed catheter). These experiments were performed by preparing a series of otherwise identical tubes coated with β-peptide-loaded films and incubating them with PBS for defined and progressively longer periods of time (up to 3 weeks) prior to the introduction of C albicans. β-peptide released into solution during these pre-incubation periods was then purged from the tubes prior to the introduction of yeast, so that any remaining antifungal activity could be determined to result from residual β-peptide remaining in the films. Six hours after the introduction of yeast, antifungal activity was quantified using a quantitative XTT assay to measure differences in cell metabolism.

The normalized metabolic activity of the inoculum recovered from each tube is shown in Figure 5. For all the pre-incubation time points tested there was a substantial and statistically significant (p < 0.05) reduction in metabolically active cells in inoculum retrieved from tubes coated with β-peptide-loaded films as compared to no-film/no-peptide and no-peptide controls. These results are interesting in view of the release profile shown in Figure 3E, which reveals that, after the first six hours of release in PBS, these films did not release incremental concentrations of β-peptide that rose above the MIC of this β-peptide over any subsequent 6-hour period (see also Table S1). Although the reasons for this are not entirely clear, we note that the data in Figure 4 demonstrate that the PGA/PLL films themselves did not exhibit significant antifungal activity. We note again, however, that the experiments performed to generate the β-peptide release profile in Figure 3E were performed in PBS, whereas the tubes used in these antifungal experiments were incubated in the presence of culture medium containing yeast cells. We speculate that the longer-term potency of the β-peptide-containing films evaluated in Figure 5 results from more rapid release of β-peptide (e.g., upon exposure to components of culture medium, by contact with cells, or resulting from the action of cell-associated proteases). More rapid release would result in overall release profiles that are shorter than the 4-month profile shown in Figure 3E. However, our current results demonstrate that these coated catheters remain potent and exhibit antifungal activity under conditions that simulate intermittent use and microbial challenge for at least three weeks.

Figure 5.

Antifungal activity of β-peptide-loaded PEMs following pre-incubation. Untreated catheters (tube; black bars), catheters coated with PGA/PLL films (tube/film; gray bars), and catheters coated with PGA/PLL films and loaded with β-peptide (tube/film/pep; white bars) were pre-incubated with PBS for the indicated time periods. Each tube was then flushed with fresh buffer before inoculation and incubation with C. albicans for 6 hours at 37 °C. XTT was then used to measure differences in cell metabolic activity. Data points are averages of measurements from two independent experiments of three replicates each normalized to the metabolic activity of the tube for each data point Error bars denote standard deviation. For all pre-incubation conditions, reductions in metabolic activity for β-peptide-loaded films (tube/film/pep) were statistically different (p < 0.05 by two-tailed T-test) from untreated controls (tube) under the same conditions.

Catheters Coated with β-Peptide-Loaded Films Inhibit C. albicans Biofilm Formation

Biofilms are distinct from planktonic cells and consist of a dense community of yeast and hyphal cells encased in an extracellular matrix.14 A number of environmental factors, including temperature, nutrient and oxygen availability, the presence of serum or host conditioning layers, etc., can promote biofilm formation.12,14,64,65 In environments and conditions suitable for biofilm formation, the presence of even just a few C albicans cells can lead to dense biofilms that ultimately necessitate device removal.8,12–14,65 We therefore also evaluated the extent to which catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films could inhibit formation of C albicans biofilms in vitro.

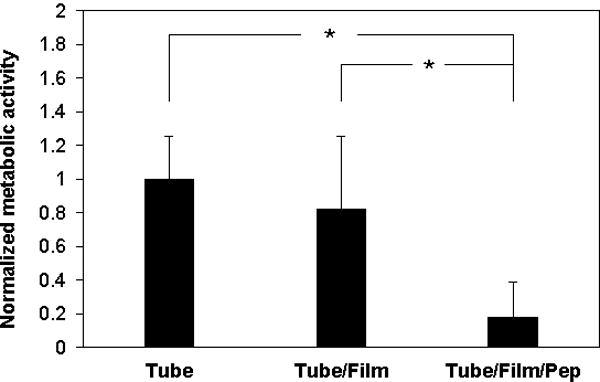

For these experiments, we incubated segments of catheter tubes with an inoculum of 106 cfu/mL of C albicans in the presence of 5% FBS at 37 °C using conditions that lead to robust biofilm growth on film-coated (no-peptide) catheter segments (see Materials and Methods for additional details). After 48 hours, the amount of biofilm formed was evaluated (i) qualitatively by inspection of longitudinally-sliced tubes using phase contrast microscopy and (ii) quantitatively using an XTT assay. Visual inspection revealed that catheters coated with β-peptide-loaded films inhibited biofilm formation significantly compared to no-film and no-peptide controls (Figure S4). Inspection of the results shown in Figure 6 reveals an ~83% decrease in biofilm in tubes coated with β-peptide-loaded films as compared to no-film/no-peptide controls. Further inspection of these results reveals that significant amounts of biofilm also formed in tubes coated with film but not loaded with β-peptide (no-peptide controls), consistent with the view that the release of β-peptide is necessary to inhibit biofilm formation.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of C. albicans by PEMs loaded with β-peptide. Untreated catheters (tube), catheters coated with PGA/PLL films (tube/film), and catheters coated with PGA/PLL films and loaded with β-peptide (tube/film/pep) were incubated with a C. albicans inoculum (106 cfu/mL) in RPMI containing 5% FBS at 37 °C. After 48 hours, XTT was used to quantify differences in biofilm metabolic activity. Data points are averages of measurements from three independent experiments of three replicates each and error bars denote standard deviation; (* indicates p < 0.005 by two-tailed T-test).

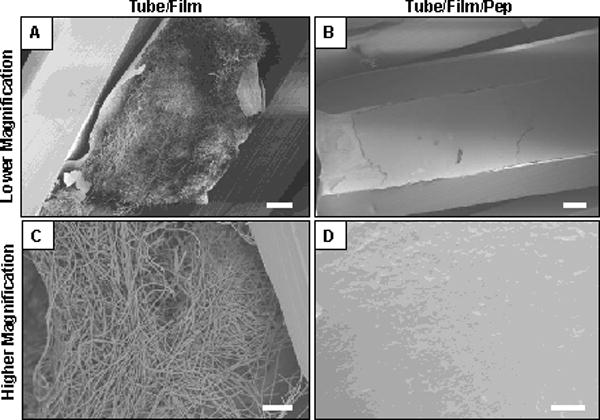

We also used SEM to characterize the morphology of the biofilms formed in these experiments (Figure 7). The images in Figure 7A and 7C show representative views of the morphologies of biofilms formed in a tube that was coated with PGA/PLL films but not loaded with β-peptide. These images reveal the presence of a dense biofilm comprised primarily of hyphal cells. The images in Figures 7B and 7D show representative views of the inner surfaces of tubes coated with β-peptide-loaded films; these images reveal the absence of biofilm. When combined, the results in Figures 6 and 7 support the conclusion that these β-peptide-loaded coatings can be used to prevent the formation of C. albicans biofilms in vitro for at least two days after inoculation.

Figure 7.

Low (A–B) and high magnification (C–D) scanning electron microscopy images showing the inner surfaces of catheter tubes after incubation with C. albicans in biofilm assays (the catheter tubes were longitudinally-sliced prior to imaging; see text for additional details of these experiments). (A,C) Images of a tube coated with a PGA/PLL film 19.5 layers thick (tube/film; no β-peptide) incubated with C. albicans for 24 hours. (B,D) Images of an otherwise identical film-coated tube loaded with β-peptide (tube/film/pep) incubated with C. albicans for 24 hours. Scale bars = 100 μm (A), 200 μm (B), 30 μm (C), 20 μm (D).

Summary and Conclusions

We have demonstrated an approach to the layer-by-layer assembly of antifungal PEMs on the inner surfaces of small-gauge catheter tubes. PGA/PLL multilayers fabricated on the insides of flexible polyethylene tubes sustained the intraluminal release of a cationic, antifungal β-peptide over a period of ~4 months when incubated in physiologically relevant media. Our results reveal the released β-peptide to remain potent against intraluminal inoculation of the catheters with planktonic C. albicans, and that this approach can substantially reduce the formation of C. albicans biofilms in film-coated catheters in vitro. Our results also demonstrate that these sustained release coatings exhibit antifungal activity under conditions that simulate intermittent catheter use and microbial challenge for at least three weeks. We conclude that β-peptide-loaded PEMs offer a novel and useful approach to kill C. albicans and prevent fungal biofilm formation on surfaces, with the potential to help prevent or substantially reduce the occurrence of device-associated infections in indwelling catheters. The focus of this study was on developing coatings useful for preventing fungal infections on the insides of small-gauge catheters. However, this general approach should also be useful for the design of β-peptide-loaded multilayers that prevent or reduce the occurrence of fungal infections on the outer surfaces of catheters or other indwelling devices. The versatility and modular nature of the layer-by-layer approach used here also suggests opportunities to exploit antifungal β-peptides (or combinations of β-peptides and other active agents or antifungal film components) in a variety of biomedical and personal care applications in which fungal infections are problematic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (1R01 AI092225). The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of facilities and instrumentation supported by the National Science Foundation through the University of Wisconsin Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-1121288). We thank Joseph Heintz and Richard Noll at the Biological & Biomaterials Preparation, Imaging, and Characterization Laboratory (BBPIC) and the Material Science Center at UW-Madison for training and help with SEM sample preparation and imaging, and Prof. Samuel H. Gellman for many helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information Available. Supporting information including evaluation of β-peptide MIC values, characterization of PEM thickness, and results of antifungal assays can be found online at doi:

References

- 1.Azie N, Neofytos D, Pfaller M, Meier-Kriesche HU, Quan SP, Horn D. The PATH (Prospective Antifungal Therapy) Alliance® registry and invasive fungal infections: update 2012. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gullo A. Invsasive Fungal Infections: The Challenge Continues. Drugs. 2009;69:65–73. doi: 10.2165/11315530-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NaR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenzel RP. Nosocomial Candidemia : Risk Factors and Attributable Mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1531–1534. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderone Ra, Fonzi Wa. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–35. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson LS, Reyes CM, Stolpman M, Speckman J, Allen K, Beney J. The direct cost and incidence of systemic fungal infections. Value Health. 2002;5:26–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojic EM, Darouiche RO. Candida Infections of Medical Devices. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:255–267. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.255-267.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramage G, Ghannoum MA, López ribot JL, Ramage Fungal Biofilms – Agents of Disease and Drug Resistance – Molecular Principles of Fungal Pathogenesis. Mol Princ Fungal Pathog. 2006:177–185. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cauda R. Candidaemia in patients with an inserted medical device. Drugs. 2009;69:33–8. doi: 10.2165/11315520-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramage G, Martínez JP, López-Ribot JL. Candida biofilms on implanted biomaterials: a clinically significant problem. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:979–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habash M, Reid G. Microbial Biofilms : Their Development and significance for medical device-related infections. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39:887–898. doi: 10.1177/00912709922008506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra J, Kuhn DM, Mukherjee PK, Hoyer LL, Mccormick T, Mahmoud A. Biofilm Formation by the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans : Development, Architecture, and Drug Resistance. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5385–5394. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5385-5394.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramage G, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Lopez-Ribot J. Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2009;35:340–55. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramage G, Saville SP, Thomas DP, López-ribot JL, Lo L. Candida Biofilms : an Update. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:633–638. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.4.633-638.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spellberg BJ, Filler SG, Edwards JE. Current treatment strategies for disseminated candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:244–51. doi: 10.1086/499057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viale P, Stefani S. Vascular catheter associated infections-A microbiological and therapeutic update. J Chemother. 2006;18:235–249. doi: 10.1179/joc.2006.18.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorrell TC. Optimizing Therapy for Candida Infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:678–688. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spellberg BJ, Filler SG, Edwards JE. Current treatment strategies for disseminated candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:244–51. doi: 10.1086/499057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghannoum Ma, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:501–17. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawser SP, Douglas LJ. Resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2128–31. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanglard D, Odds FC. Resistance of Candida species to antifungal agents : molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill RJ. Amphotericin B formulations: a comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs. 2013;73:919–34. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen BE. Amphotericin B toxicity and lethality: a tale of two channels. Int J Pharm. 1998;162:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van ’t Hof W, Veerman EC, Helmerhorst EJ, Amerongen aV. Antimicrobial peptides: properties applicability. Biol Chem. 2001;382:597–619. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancock REW, Chapple DS. Peptide Antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1317–1323. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hancock REW, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlsson AJ, Pomerantz WC, Neilsen KJ, Gellman SH, Palecek SP. Effect of Sequence and Structural Properties on 14-Helical -Peptide Activity against Candida albicans Planktonic Cells and Biofilms. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:567–579. doi: 10.1021/cb900093r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson AJ, Pomerantz WC, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, Palecek SP. Antifungal activity from 14-helical beta-peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12630–1. doi: 10.1021/ja064630y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter Ea, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. Mimicry of host-defense peptides by unnatural oligomers: antimicrobial beta-peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7324–30. doi: 10.1021/ja0260871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raguse TL, Porter Ea, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. Structure-activity studies of 14-helical antimicrobial beta-peptides: probing the relationship between conformational stability and antimicrobial potency. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12774–85. doi: 10.1021/ja0270423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter EA, Wang X, Lee H, Weisblum B. Non-haemolytic beta-amino-acid oligomers. Nature. 2000;404:565. doi: 10.1038/35007145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson AJ, Flessner RM, Gellman SH, Lynn DM, Palecek SP. Polyelectrolyte multilayers fabricated from antifungal β-peptides: design of surfaces that exhibit antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:2321–8. doi: 10.1021/bm100424s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu P, Grainger DW. Drug/device combinations for local drug therapies and infection prophylaxis. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2450–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hetrick EM, Schoenfisch MH. Reducing implant-related infections: active release strategies. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:780–9. doi: 10.1039/b515219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, Subbiahdoss G, Jutte PC, van den Dungen JJaM, Zaat SaJ, Schultz MJ, Grainger DW. Biomaterial-associated infection: locating the finish line in the race for the surface. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:153rv10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Eiff C, Jansen B, Kohnen W, Becker K. Infections associated with medical devices: pathogenesis, management and prophylaxis. Drugs. 2005;65:179–214. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Page K, Wilson M, Parkin IP. Antimicrobial surfaces and their potential in reducing the role of the inanimate environment in the incidence of hospital-acquired infections. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:3819. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasilev K, Cook J, Griesser HJ. Antibacterial surfaces for biomedical devices. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:553–67. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lichter Ja, Van Vliet KJ, Rubner MF. Design of Antibacterial Surfaces and Interfaces: Polyelectrolyte Multilayers as a Multifunctional Platform. Macromolecules. 2009;42:8573–8586. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campoccia D, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. A review of the biomaterials technologies for infection-resistant surfaces. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8533–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marsich E, Travan a, Donati I, Turco G, Kulkova J, Moritz N, Aro HT, Crosera M, Paoletti S. Biological responses of silver-coated thermosets: an in vitro and in vivo study. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:5088–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar R, Münstedt H. Silver ion release from antimicrobial polyamide/silver composites. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2081–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neel EaA, Ahmed I, Pratten J, Nazhat SN, Knowles JC. Characterisation of antibacterial copper releasing degradable phosphate glass fibres. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaonkar TA, Sampath LA, Modak SM. Evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of urinary catheters impregnated with antiseptics in an in vitro urinary tract model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;24:506–513. doi: 10.1086/502241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sampath LA, Tambe SM, Modak SM. In Vitro and In Vivo Efficacy of Catheters Impregnated With Antiseptics or Antibiotics: Evaluation of the Risk of Bacterial Resistance to the Antimicrobials in the Catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:640–646. doi: 10.1086/501836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shukla A, Fang JC, Puranam S, Hammond PT. Release of vancomycin from multilayer coated absorbent gelatin sponges. J Control Release. 2012;157:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cado G, et al. Self-Defensive Biomaterial Coating Against Bacteria and Yeasts: Polysaccharide Multilayer Film with Embedded Antimicrobial Peptide. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:4801–4809. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Etienne O, Picart C, Taddei C, Haikel Y, Dimarcq JL, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Ogier JA, Egles C. Multilayer Polyelectrolyte Films Functionalized by Insertion of Defensin : a New Approach to Protection of Implants from Bacterial Colonization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3662–3669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3662-3669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etienne O, Gasnier C, Taddei C, Voegel JC, Aunis D, Schaaf P, Metz-Boutigue MH, Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Egles C. Antifungal coating by biofunctionalized polyelectrolyte multilayered films. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6704–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carpenter AW, Worley BV, Slomberg DL, Schoenfisch MH. Dual action antimicrobials: nitric oxide release from quaternary ammonium-functionalized silica nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:3334–42. doi: 10.1021/bm301108x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hetrick EM, Shin JH, Stasko NA, Johnson BC, Wespe DA, Holmuhanedov E, Schoenfisch MH. Bactericidal efficacy of nitric oxide-releasing silica nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2008;2:235–246. doi: 10.1021/nn700191f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christensen LD, van Gennip M, Jakobsen TH, Alhede M, Hougen HP, Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M. Synergistic antibacterial efficacy of early combination treatment with tobramycin and quorum-sensing inhibitors against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an intraperitoneal foreign-body infection mouse model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1198–206. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Broderick AH, Stacy DM, Tal-Gan Y, Kratochvil MJ, Blackwell HE, Lynn DM. Surface coatings that promote rapid release of peptide-based AgrC inhibitors for attenuation of quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3:97–105. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lichter Ja, Van Vliet KJ, Rubner MF. Design of Antibacterial Surfaces and Interfaces: Polyelectrolyte Multilayers as a Multifunctional Platform. Macromolecules. 2009;42:8573–8586. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Decher G. Fuzzy Nanoassemblies: Toward Layered Polymeric Multicomposites. Science. 1997;277:1232–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammond PT. Engineering Materials Layer-by-Layer : Assembly. AIChE J. 2011;57:2928–2940. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jewell CM, Lynn DM. Multilayered polyelectrolyte assemblies as platforms for the delivery of DNA and other nucleic acid-based therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:979–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schultz P, Vautier D, Richert L, Jessel N, Haikel Y, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Ogier J, Debry C. Polyelectrolyte multilayers functionalized by a synthetic analogue of an anti-inflammatory peptide, alpha-MSH, for coating a tracheal prosthesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2621–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lavalle P, Gergely C, Cuisinier FJG, Decher G, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Picart C. Comparison of the Structure of Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Films Exhibiting a Linear and an Exponential Growth Regime: An in Situ Atomic Force Microscopy Study. Macromolecules. 2002;35:4458–4465. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richert L, Arntz Y, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Picart C. pH dependent growth of poly(L-lysine)/poly(L-glutamic) acid multilayer films and their cell adhesion properties. Surf Sci. 2004;570:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Facca S, Cortez C, Mendoza-Palomares C, Messadeq N, Dierich a, Johnston aPR, Mainard D, Voegel JC, Caruso F, Benkirane-Jessel N. Active multilayered capsules for in vivo bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3406–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jessel N, Atalar F, Lavalle P, Mutterer J, Decher G, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Ogier J. Bioactive Coatings Based on a Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Architecture Functionalized by Embedded Proteins. Adv Mater. 2003;15:692–695. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumamoto Ca. Candida biofilms. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:608–11. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumamoto Ca, Vinces MD. Alternative Candida albicans lifestyles: growth on surfaces. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:113–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.