Abstract

Little is known about how neighborhood perceptions are related to diabetes outcomes among Latinos living in rural agricultural communities. Our objective was to examine the association between perceived neighborhood problems and diabetes outcomes. This is a cross-sectional survey study with medical record reviews of a random sample of 250 adult Latinos with type 2 diabetes. The predictor was a rating of patient ratings of neighborhood problems (crime, trash and litter, lighting at night, and access to exercise facilities, transportation, and supermarkets). The primary outcomes were the control of three intermediate outcomes (LDL-c <100 mg/dl, AlC < 9.0%, and blood pressure (BP) < 140/80 mmHg), and body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2. Secondary outcomes were participation in self-care activities (physical activity, healthy eating, medication adherence, foot checks, and glucose checks). We used regression analysis and adjusted for age, gender, education, income, years with diabetes, insulin use, depressive symptoms, and co-morbidities. Forty-eight percent of patients perceived at least one neighborhood problem and out of the six problem areas, crime was most commonly perceived as a problem. Perception of neighborhood problems was independently associated with not having a BP < 140/80 (Adjusted odds ratio [AOR]= 0.45; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.92), and BMI < 30 (AOR=0.43; 95% CI: 0.24, 0.77), after controlling for covariates. Receipt of recommended processes of care was not associated with perception of neighborhood. Perception of neighborhood problems among low-income rural Latinos with diabetes was independently associated with a higher BMI and BP.

Keywords: Latinos, neighborhood, health behaviors, rural, diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Neighborhood and environment are important determinants of health in addition to individual characteristics and contributions of the health care system. Individuals living in poor neighborhoods are at increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. [1–3] For the 26 million in the United States that have diabetes, [4] neighborhood plays an important role in health and health behavior. Clinical guidelines recommend that patients with diabetes eat certain foods, exercise regularly and participate in other recommended self-care activities. [5] These recommendations can be difficult to follow for individuals that have limited access to stores that sell healthy foods and places to exercise. [6–9]

For Latinos that face disparities in diabetes care, [10–14] residing in low-income areas with crime, litter, and dilapidated housing may produce complicated psycho-social perceptions of their neighborhood that discourage these healthy behaviors. In one study of managed care patients, perceived neighborhood problems were independently associated with poor health behaviors and elevated blood pressure among individuals with diabetes. [15] No other study that we are aware of has investigated the relation between perceived neighborhood problems and worse self-care behaviors and poor health-related outcomes among those with diabetes. [15–19] We know even less about how neighborhood problems might influence these outcomes in Latinos with diabetes. Among Latinos, neighborhood economic disadvantage is an important predictor of self-rated health status, [20] but paradoxically living in areas with higher numbers of Latinos may confer some protection to health. [21] Latinos from rural agricultural communities have been historically among the most disadvantaged in the United States. How the rural residential context may affect their participation in beneficial self-care behaviors has not been studied. [22–24]

In this study, we examined whether perceived neighborhood problems were independently associated with health behaviors and diabetes-related clinical outcomes among rural Latinos. We hypothesized that perceived neighborhood problems would be associated with less participation in recommended self-care behaviors and poor diabetes-related outcomes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Conceptual Framework

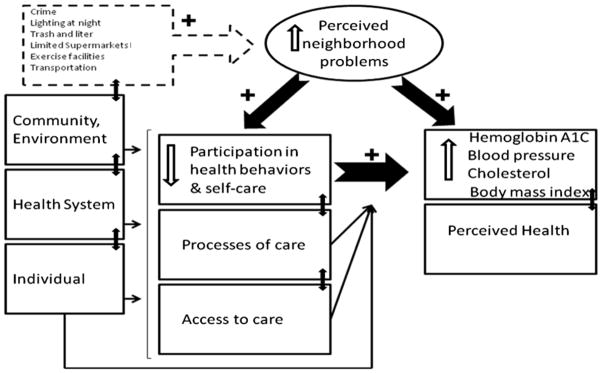

We used Brown et al.’s conceptual framework of socioeconomic position and health among persons with diabetes mellitus [25] to guide our study and explain the interplay of neighborhood with diabetes-related outcomes. The model posits that two types of factors (proximal and distal) influence the relation between socioeconomic position and health for persons with diabetes. Proximal factors include health behaviors, processes of care, and access; and distal factors include characteristics of persons with diabetes, their health care system including providers, and their communities or neighborhood. In this model, critical covariates (age, gender, and race-ethnicity) may have an independent effect on the relation between neighborhood and health. Poor persons with diabetes are more likely to experience different elements of poor neighborhoods such as higher priced foods, dilapidated housing, and high crime. [26] Figure 1 is a simplified schematic of the conceptual framework adapted for this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Source: Brown, A.F., et al., Socioeconomic position and health among persons with diabetes mellitus: a conceptual framework and review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev, 2004. 26: p. 63–77.

Setting

We used principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) that included both academic and community partners working collaboratively in all aspects of the research from study design to dissemination. [27, 28] The study was conducted in partnership with a large migrant health center that provides safety-net care in two rural counties in California’s San Joaquin Valley, an agricultural region with long-standing poverty. [29] One of these counties ranks worst in the state for obesity prevalence and in the bottom five for overweight, participation in physical activity, and consumption of fruits or vegetables. [30, 31] The region has one of the highest diabetes prevalence rates in this state [32] and patients with diabetes from this region have a high risk for poor diabetes outcomes. [33, 34]

Sample and data sources

We conducted a cross-sectional survey between July 2009 and January 2010 among 250 Latino adults with diabetes. Study inclusion criteria were: (1) self-identified as Latino; (2) spoke Spanish; (3) had a current diagnosis of diabetes type 2; (4) 18 years of age or older; and (5) at least two primary care visit for diabetes care in the last 12 months.

A list of potential participants was generated from an electronic diabetes registry (n=5,128). The registry captures health information for over 90% of diabetics in the system. Clinic staff randomly called eligible patients and asked them to participate in the survey study. The survey was administered by telephone in Spanish after verbal consent was obtained. Patients were called up to 15 times during different days and times of the week and the survey response rate was 68%. Inaccurate contact information was the primary reason for survey non-response. The medical chart of all survey participants was reviewed for the most recent blood pressure, height, and weight. The survey was pre-tested with volunteer patients and bilingual health workers to assess the skip pattern. The study was approved by the RAND (Santa Monica, CA) protection of human subjects review committee (IRB).

Main independent variables

The primary predictor variable was perceived neighborhood problems as measured with validated items that were adapted from the Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. [15, 35] Participants were asked “thinking about where you live, how much of a problem are each of the following issues: (1) Crime in area; (2) Access to exercise facilities; (3) Trash and liter; (4) Lighting at night; (5) Access to public transportation; and (6) Access to supermarkets. Response options for each item were: very serious, somewhat serious, minor, or not a problem.” Responses to this set of items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86) were summed to calculate a summary score (range: 1–24, mean 21, best = 24). Because the distribution of the summary score was skewed, patients were classified into two groups (no problems versus one or more problems). Those that responded not a problem to all six items were put into the no problem category.

Dependent variables

Dependent variables examined were hemoglobin A1C (A1C), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-c), blood pressure (BP), and body mass index (BMI). The patient medical records were reviewed 1 to 4 weeks after the interview using a published chart abstraction tool. [35] BMI was calculated using patient’s weight and height obtained from medical record and classified as normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI>30 kg/m2). A1C, LDL-c, BMI, and BP values were all collected through electronic registry and medical record reviews and dichotomized as A1C <9%, LDL-c < 100 mg/dL, BMI < 30 kg/m2, and BP < 140/80 mmHg based on recommended clinical targets. Receipt of 6 recommended diabetes processes of care [36] was ascertained by asking patients if in the last 12 months they had received: a dilated eye exam, flu vaccine, foot exam, LDL-c blood test, A1C blood test, and were taking or recommended aspirin (all dichotomous: yes or no). We used the Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities (SCDA) questionnaire to measure patient participation over the last seven days in foot care, eating a healthy diet, exercise, medication adherence, and glucose self-monitoring. [37]

Other variables

Based on Brown et al.’s conceptual model, we measured other important variables. Patients were queried about their satisfaction with their neighborhood with one global item (All things considered, which of the following best describes your neighborhood as a place to live - would you say you are very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied?). [35] The presence of depressive symptoms was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2). [38, 39] Self-reported health status was measured by asking participants, “In general, would you say your health status is: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?” and classifying responses into excellent/very good/good, fair or poor. Severity of diabetes was ascertained by determining the years with diabetes and use of insulin. Co-morbidities were captured from the medical chart (hypertension, elevated cholesterol, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, asthma, cerebrovascular disease, and emphysema [dichotomous: yes or no]). We also examined household size, housing type and the number of years a patient lived in their current location.

We examined several patient sociodemographic characteristics: age (categorized as 21–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, or ≥ 70 years), gender, marital status, birthplace (United States, Mexico, or other country), years in the U.S., and education (categorized as 0–6 years, 7–11 years, or ≥ 12 years of regular school completed). Patients were asked about utilization (number of doctor visits, and emergency visits) in the last 12 months, health insurance coverage of any kind (dichotomous: yes or no), and yearly household income (0–12,499 dollars, 12,500–17,499 dollars, 17,500–24,999 dollars or 25,000 or more dollars).

Statistical analyses

We computed distributions for our dependent and independent variables and then performed bivariate analyses of perceived neighborhood problems by patient demographic characteristics and health-related measures. Bivariate associations were assessed using 2 tests of association for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. For all analyses reported in this study, a p-value of < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Stata version 11.1 (College Station, TX) was used for these analyses.

In the regression models we controlled for age, gender, education, household income, the number of co-morbidities, use of insulin, and years with diabetes. Covariates were included if they were potential confounders based on Brown et al.’s conceptual model, [25] our review of the literature or if they were statistically significant in bivariate analysis. Logistic regression models were computed for each outcome variable (A1C < 9%, LDL-c < 100 mg/dL, BMI < 30 kg/m2, and BP < 140/80 mmHg). We performed the analysis using the summary neighborhood problems score as a continuous variable but found little difference from that reported (data not shown). We also conducted post-hoc analyses to assess whether including the number of clinic visits, number of ER visits, years in the U.S., and birthplace affected the magnitude or direction of coefficients but the results were similar to those reported (data no shown).

We conducted a series of staged linear regression models for BMI to isolate the effect of neighborhood form proximal variables (health behaviors) found to be significantly associated with BMI. In model 1, we included age, gender, education, years with diabetes, and exercising (proximal variable). In model 2, we controlled for model 1 covariates and neighborhood perception. In model 3, we controlled for model 2 covariates plus depressive symptoms.

RESULTS

Forty-eight percent of patients perceived at least one neighborhood problem. The percentage of patients that perceived each of the six different neighborhood areas as a problem ranged from 21% to 32%. Out of the six problem areas, crime was the most commonly perceived problem compared to the other areas. Table 1 describes differences in sociodemographic and health-related characteristics among participants by perceived neighborhood problems. Among patients that perceived one or more neighborhood problems, mean BMI was higher (35.8 vs. 32.4 kg/m2, p<0.01) and mean PHQ-2 scores were higher (2.0 vs. 1.6, p<0.001) than those without perceived problems. Patients that perceived one or more neighborhood problems were more likely to be dissatisfied/very dissatisfied with overall neighborhood satisfaction (p = 0.001) compared to those that did not perceive a neighborhood problem.

Table 1.

Associations between patient characteristics and perceived neighborhood problems among rural Latinos with diabetes (N=250)

| Perceived Neighborhood Problems* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No problems (n= 131) | One or more problems (n= 119) | P† | |

| Age, years, % | |||

| 18–39 | 11.6 | 10.7 | 0.50 |

| 40–49 | 26.4 | 24.8 | |

| 50–59 | 22.5 | 32.2 | |

| 60–69 | 21.7 | 19.0 | |

| ≥ 70 | 17.8 | 13.2 | |

| Female, % | 56.8 | 61.7 | 0.44 |

| Married/Living with someone, % | 78.1 | 74.8 | 0.35 |

| Education, years, % | |||

| 0–6 | 62.6 | 65.2 | 0.82 |

| 7–11 | 19.2 | 16.0 | |

| ≥ 12 | 18.1 | 18.8 | |

| Income, yearly, % | |||

| $0–12,499 | 34.9 | 27.1 | 0.68 |

| $12,500–17,499 | 22.9 | 25.9 | |

| $17,500–24,999 | 20.5 | 25.9 | |

| $25,000 or more | 21.7 | 21.2 | |

| Birthplace, % | |||

| U.S. | 18.5 | 17.7 | 0.73 |

| Mexico | 78.5 | 77.3 | |

| Other country | 3.1 | 5.0 | |

| Years in the U.S., mean (SD) | 30.7 (15.9) | 29.6 (16.3) | 0.59 |

| Years in current community, mean (SD) | 15.8 (13.6) | 13.4 (11.4) | 0.15 |

| Live in single family home or house, % | 84.0 | 79.8 | 0.40 |

| Household size, mean (SD) | 4.4 (3.3) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.54 |

| Neighborhood satisfaction‡, % | |||

| Very satisfied | 23.2 | 14.0 | 0.001 |

| Satisfied | 72.2 | 68.6 | |

| Dissatisfied/Very dissatisfied | 4.7 | 17.4 | |

| Self-assessed health status‡, % | |||

| Poor | 7.4 | 14.4 | 0.18 |

| Fair | 66.1 | 64.4 | |

| Good/Very Good/Excellent | 26.5 | 21.2 | |

| PHQ-2 score§, mean (SD) | 1.6 (.7) | 2.0 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Insurance, any, % | 59.1 | 55.5 | 0.57 |

| Years with diabetes, mean (SD) | 9.4 (8.1) | 10.3 (9.9) | 0.40 |

| Insulin use, % | 19.9 | 21.9 | 0.70 |

| Body mass index (BMI) kg/m2, mean (SD) | 32.4 (8.0) | 35.8 (10.5) | 0.004 |

| Number of ER visits, || mean (SD) | 0.57 (1.6) | 0.54 (1.5) | 0.88 |

| Number of primary care visits, || mean (SD) | 0.57 (2.3) | 3.8 (3.1) | 0.64 |

1) crime in area, 2) access to recreational or exercise facilities, 3) trash or litter, 4) lighting at night, 5) access to public transportation, and 6) access to a supermarket;

calculated using χ2 statistical test;

assessed with one global health item;

range: 1–4; best = 1; mean for the two PHQ-2 questionnaire items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.85;

mean number of visits during the last 12 months;

range 1–7; best =7, days of participation in self-care activity/behavior over the last week

SD=standard deviation

Mean systolic BP was 4.5 mm Hg higher (p = 0.06) for patients that perceived neighborhood problems compared to those without neighborhood problems. Mean A1c and LDL-c levels did not differ by neighborhood problems. Table 2 shows the unadjusted proportion of patients with control of intermediate clinical outcomes (LDL-c, A1C, BP, BMI), participation in self-care activities, and rates of receipt of recommended processes of care for participants stratified by whether they perceived one or more neighborhood problems. Those with neighborhood problems where less likely to have a BMI < 30 kg/m2 and/or a BP < 140/80 mmHg and less participation in self care (physical activity/exercise, healthful eating, and self-foot exams) compared to counterparts without perceived problems (all p< 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in receipt of processes of care by groups. Patients with perceived problems were more likely to participate less in health behaviors (physical activity and exercise, healthful eating, self-foot exams).

Table 2.

Unadjusted percentages of patients with control of measures for diabetes outcomes, care, and health behaviors by perceived neighborhood problems among Latinos with diabetes (N=250)

| Perceived Neighborhood Problems† | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No problems | One or more problem | P-value‡ | |

|

| |||

| Clinical Outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| Hemoglobin A1C <9% | 80.3 | 76.2 | 0.43 |

|

| |||

| LDL-cholesterol < 130 mg/dL | 87.9 | 84.2 | 0.41 |

|

| |||

| Blood pressure < 140/80 mmHg | 90.2 | 80.7 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2 | 41.7 | 23.3 | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Health Care (receipt of processes of care)§ | |||

|

| |||

| Aspirin, or recommended aspirin by provider | 75.2 | 77.3 | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| LDL-cholesterol test checked | 82.2 | 83.1 | 0.81 |

|

| |||

| A1C test checked | 56.8 | 54.1 | 0.65 |

|

| |||

| Foot exam | 39.7 | 42.0 | 0.71 |

|

| |||

| Flu vaccine | 43.1 | 50.4 | 0.35 |

|

| |||

| Eye exam | 58.5 | 51.3 | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| Health Behaviors | |||

|

| |||

| Participation in Self-Care Activities,* mean (SD) | |||

|

| |||

| Physical activity & exercise | 3.57 | 2.91 | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Healthful eating plan | 5.54 | 4.93 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Self-foot exams | 1.46 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Glucose checks | 4.61 | 4.87 | 0.43 |

|

| |||

| Medication adherence | 6.89 | 6.73 | 0.12 |

In the last seven days

1) crime in area, 2) access to recreational or exercise facilities, 3) trash or litter, 4) lighting at night, 5) access to public transportation, and 6) access to a nearby supermarket. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86.

calculated using chi square statistical test

during the last 12 months

Table 3 shows results from the logistic regression analysis for the 4 primary outcomes (A1C < 9%, BP < 140/80mmHg, LDL-c < 100 mg/dL, BMI < 30 kg/m2) as a function of perceived neighborhood problems controlling for demographic characteristics, years with diabetes, insulin use, exercise/physical activity, and PHQ-2 scores. Table 4 shows the linear regression results for BMI as a function of exercise/physical activity behavior. In model 2 of Table 4, the addition of perceived neighborhood problems slightly attenuated the independent effect of exercise/physical activity on BMI. The addition of depressive symptoms in model 3 did not attenuate the effect of participation in exercise/physical activity. In the final model (3), for each additional day of participation in exercise/physical activity, BMI decreased by 0.5 kg/m2. Perception of neighborhood problems was associated with a 2.9 kg/m2 increase in BMI compared to their counterparts.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of control of outcomes by perceived neighborhood problems among rural Latinos with diabetes (N=250)

| Perceived Neighborhood problems* |

BP < 140/80 mmHg AOR (95% CI) |

A1C < 9% AOR (95% CI) |

LDL-c < 100 mg/dL AOR (95% CI) |

BMI < 30 kg/m2 AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more problems | 0.45† (0.22, 0.92) | 0.71 (0.37, 1.37) | 0.89 (0.52, 1.51) | 0.43‡ (0.24, 0.77) |

| No problems | ref | ref | ref | ref |

Note: adjusted for age, gender, education, income, years with diabetes, insulin use, number of co-morbidities, and PHQ-2 mean score

1) crime in area, 2) access to recreational or exercise facilities, 3) trash or litter, 4) lighting at night, 5) access to public transportation, and 6) access to a supermarket; Cronbach’s alpha=0.86

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = confidence intervals; BP = blood pressure; BMI = body mass index; ref= reference category

Table 4.

Adjusted linear regression for BMI as a function of perceived neighborhood problems, health behaviors, and depressive symptoms, and other variables among rural Latinos with diabetes (N=250)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Health Behaviors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Exercise/physical activity | −0.58 | 0.23 | −0.47 | 0.23 | −0.49 | 0.24 |

|

| ||||||

| Perception of Neighborhood* | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No problems | --- | --- | −2.98 | 1.22 | −2.85 | 1.24 |

|

| ||||||

| One or more problem | --- | --- | ref | --- | ref | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms† | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.43 | 0.79 |

|

| ||||||

| R2 | 0.119 | 0.138 | 0.144 | |||

All models adjusted for age, gender, education, income, number of co-morbidities, years with diabetes, and insulin use

Bold = P-value < 0.05

perceived problems = 1) crime in area, 2) access to recreational or exercise facilities, 3) trash or litter, 4) lighting at night, 5) access to public transportation, and 6) access to a supermarket; Cronbach’s alpha=0.86

measured with PHQ-2

β = beta coefficient

SE=standard error

ref = reference category

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that perceived neighborhood problems were independently associated with less participation in exercise and elevated BP and BMI. Exercising did not appreciably attenuate the positive association between neighborhood perception and BMI. We also found that depressive symptoms were independently associated with perception of neighborhood problems. We did not find a significant association between perception of neighborhood problems and levels of A1C and LDL-c. as measured. Our main findings are in agreement with Brown et al.’s conceptual framework that predicts that neighborhood problems are associated with health-related outcomes for persons with diabetes.

This is the first study that we are aware of that examines the association between perceived neighborhood problems and diabetes outcomes among rural Latinos. Obesity and diabetes are serious health problems in this population. This study adds to the few existing studies of neighborhood perception among those who already have diabetes. [1, 15, 18, 19, 40, 41] Our results are in agreement with a similar study that focused on patients with diabetes in managed care that linked perception of neighborhood problems with health behaviors [15], and extend those finding to include these results for rural Latinos with diabetes. Latinos are now the largest minority group in the country and face disparities in diabetes care. [10–14] This study focuses on understudied and vulnerable patients in care at a large migrant health center and makes a unique contribution to the literature.

Our finding that neighborhood perception is independently associated with depressive symptoms is in agreement with studies of other populations. [42–44] Income and receipt of recommended processes of care [41] were not associated with perception of neighborhood. Because our sample of patients have access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care (35 year-old migrant center) [45] and represents a compressed portion of the SES gradient (rural low-income Latinos), we think that this was due to lack of variation in the sample and is therefore not surprising.

This study has limitations. The cross-sectional design does not allow for inference of casual relationships. We used self-reports which are subject to recall bias and socially desirable answers. Our results cannot be generalized to all patients with diabetes, other chronic conditions or all Latinos. We focused on one rural agricultural region and the results may also not be generalized to other farmworker communities or agricultural regions in the country. We cannot entirely discount reverse directionality of the associations observed or that poor health leads to perceived neighborhood problems. There is evidence that neighborhood environment contributes to health, [3] but the mechanism remains unclear. Perceived neighborhood problems may not reflect objective differences across neighborhoods, [46] but previous studies have found that perceived neighborhood problems correlate well with objective measures of neighborhood such as census track indices of SES disadvantage status. [15, 47–50] Subjective measures of neighborhood [51] are better suited for studying its relationship with individual behaviors such as exercising and healthy eating. [42, 52–54]

Our results have policy and research implications. Studies indicate that individual factors and health care do not explain the entire disparities gap for racial-ethnic minorities and that the context of residential place contributes significantly. [55] Addressing social determinates of health are particularly important targets for interventions in this rural population. A CBPR approach allowed us to reach this understudied population. [27, 28]

There is a need for the implementation of place-based or community-based health interventions that simultaneously address individual and system-based factors to improve health behaviors that affect health outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Moreno received support from an NIA (K23 AG042961-01) Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award, the American Federation for Aging Research, and the California Endowment. Drs. Moreno and Mangione were supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars® Program at UCLA, and by the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA grant P30AG021684, and the content does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA/NIH.

References

- 1.Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Kiefe CI. Neighborhood characteristics and components of the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(11):1976–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diez Roux AV, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig J, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes--a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1509–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank LD, Andresen MA, Schmid TL. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1761–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horowitz CR, et al. Barriers to buying healthy foods for people with diabetes: evidence of environmental disparities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(9):1549–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kipke MD, et al. Food and park environments: neighborhood-level risks for childhood obesity in east Los Angeles. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(4):325–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowie CC, et al. Disparities in incidence of diabetic end-stage renal disease according to race and type of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(16):1074–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young BA, et al. Effects of ethnicity and nephropathy on lower-extremity amputation risk among diabetic veterans. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(2):495–501. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavery LA, et al. Variation in the incidence and proportion of diabetes-related amputations in minorities. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(1):48–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris MI, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):403–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MMWR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2004. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics: selected areas, 1998–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gary TL, et al. Perception of neighborhood problems, health behaviors, and diabetes outcomes among adults with diabetes in managed care: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):273–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen DA, et al. Neighborhood physical conditions and health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):467–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auchincloss AH, et al. Association of insulin resistance with distance to wealthy areas: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(4):389–97. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabi DM, et al. Association of socio-economic status with diabetes prevalence and utilization of diabetes care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:124. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook RD, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and traffic-related air pollution. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(1):32–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815dba70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel KV, et al. Neighborhood context and self-rated health in older Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9):620–8. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eschbach K, et al. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: is there a barrio advantage? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1807–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuomilehto J, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen D, et al. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):230–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannon L, 3rd, Sawyer P, Allman RM. The influence of community and the built environment on physical activity. J Aging Health. 2012;24(3):384–406. doi: 10.1177/0898264311424430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown AF, et al. Socioeconomic position and health among persons with diabetes mellitus: a conceptual framework and review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:63–77. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liese AD, et al. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1916–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno G, et al. Eight years of building community partnerships and trust: the UCLA family medicine community-based participatory research experience. Acad Med. 2009;84(10):1426–33. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6c16a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S81–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Congressional Research Service. The Library of Congress; 2005. California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Region in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarte L, et al. The Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program: changing nutrition and physical activity environments in California’s heartland. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2124–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.203588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diabetes in California Counties: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Resources. California Diabetes Control Program, California Department of Health Services; Sacramento, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamant AL, et al. Diabetes: The Growing Epidemic. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.County Health Status Profiles. California Department of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarejo D, et al. Suffering in Silence: A Report on the Health of California’s Agricultural Workers. California Institute of Rural Studies; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study: a multicenter study of diabetes in managed care. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):386–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangione CM, et al. The association between quality of care and the intensity of diabetes disease management programs. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(2):107–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–50. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbody S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1596–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gary-Webb TL, et al. Neighborhood and weight-related health behaviors in the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:312. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billimek J, Sorkin DH. Self-reported Neighborhood Safety and Nonadherence to Treatment Regimens Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1882-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Muntaner C. When being alone might be better: neighborhood poverty, social capital, and child mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):227–37. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37(4):293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latkin CA, Curry AD. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(1):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunez de Jaimes F, et al. Implementation of language assessments for staff interpreters in community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(3):1002–9. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diez Roux AV. Invited commentary: places, people, and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(6):516–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balfour JL, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(6):507–15. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weden MM, Carpiano RM, Robert SA. Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1256–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen M, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: an analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2575–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laraia BA, et al. Place matters: neighborhood deprivation and cardiometabolic risk factors in the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(7):1082–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Echeverria SE, Diez-Roux AV, Link BG. Reliability of self-reported neighborhood characteristics. J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):682–701. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman IKLF, editor. Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “Broken windows”. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(4):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Do DP, et al. Does place explain racial health disparities? Quantifying the contribution of residential context to the Black/white health gap in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]