Introduction

Innovations in chemotherapy treatments are leading to increased survival rates among lymphoma patients. Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) is the most common hematologic malignancy and one of the most common cancers in adolescents and young adults. The incidence of NHL has increased 2-fold over the past twenty years. Chemotherapy regimens for NHL always include cyclophosphamide, which is well-known to be gonadotoxic in an age- and dose-dependant manner [1–4].

The incidence of premature ovarian failure in case of NHL is about 5 % after CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), 14 % after hyper-CVAD (cyclophosxphamide, vincristine, adriamycine, dexamethasone) and 70–100 % after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), with pregnancy rates of 50 %, 43 % and less than 5 %, respectively [5–7].

A large retrospective survey of 37 362 patients revealed that only 0.6 % of those patients conceived after autologous or allogenic stem cell transplantation [8]. In this respect, information about chemo-induced infertility in haematological malignancy needs to be given and fertility preservation options should be discussed with patients before treatment [7, 9, 10].

Ovarian cryopreservation is currently required when the risk of infertility is more than 50 % [11] and/or when chemotherapy cannot be delayed sufficiently enough for performing mature oocyte cryopreservation after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation [12].

Over the last decades, about 60 patients underwent cryopreserved ovarian tissue auto-transplantation, in the purpose to restore fertility after a gonadotoxic treatment, resulting in 24 live births [13]. Pregnancies were obtained after orthotopic transplantation and occurred either spontaneously or after IVF [13, 14]. Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) and Non Hodgkin Lymphoma are common indications of ovarian cryopreservation [10, 13, 14]. To date, fifteen auto-transplantations have been performed for HL and six for NHL respectively without any disease recurrence [13]. Nevertheless, Bittinger et al. recently showed an ovarian involvement of a stage III HL within the ovarian cortex pieces systematically assessed for the presence of tumor cells before storage [15]. We currently report the histological detection of NHL cells within the ovarian tissue removed for subsequent cryopreservation in a 24-year-old woman diagnosed with a Primary Mediastinal large B-cell Lymphoma.

Material and methods

A 24-year-old woman without significant medical history consulted for a superior cava venae syndrome. A NHL with supraclavicular and axillary location was suspected following a supraclavicular lymph node’s biopsy during the exploration of this superior cava venae syndrome. Positron Emission Tomography with 18 F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), which is presented in Fig. 1, confirmed an intense uptake of the mediastinal lymphe nodes, associated with a nodular splenic lesion. A slight uptake is also described in the left pelvic area (Fig. 1). The bone marrow examination did not show evidence of tumor involvement. The clinical stage was III with an international prognosis index of 2. Given these unfavourable features, the patient required an urgent chemotherapy regimen that included alkylating agents with the CVAD protocol (Doxorubicine 300 g/m2, Cyclophosphamide 4 800 mg/m2, Vinblastine 16 mg/m2, Bléomycine 80 mg/m2 and Prednisone) associated with the monoclonal antibody anti-CD20 (Rituximab®). Consequently, the patient was urgently referred to our fertility preservation unit in order to examine the indication of ovarian tissue harvesting. The patient was nulliparous and normally cycling. Her pre-treatment ovarian reserve was assessed through AMH levels and transvaginal ultrasonographic assessment of the antral follicle count (AFC). The serum AMH level was of 32 pmol/l and the total number of antral follicles was 24. The patient gave her informed consent regarding ovarian removal for cryopreservation under laparoscopic guidance. She also gave her informed consent to be enrolled in a follow-up of her ovarian reserve marker during and after chemotherapy by performing serial AMH and AFC measurements for 2 consecutive years according to our previously-reported protocol [16].

Fig. 1.

Slight uptake in the left pelvic area at the positron Emission Tomography with 18 F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

Results

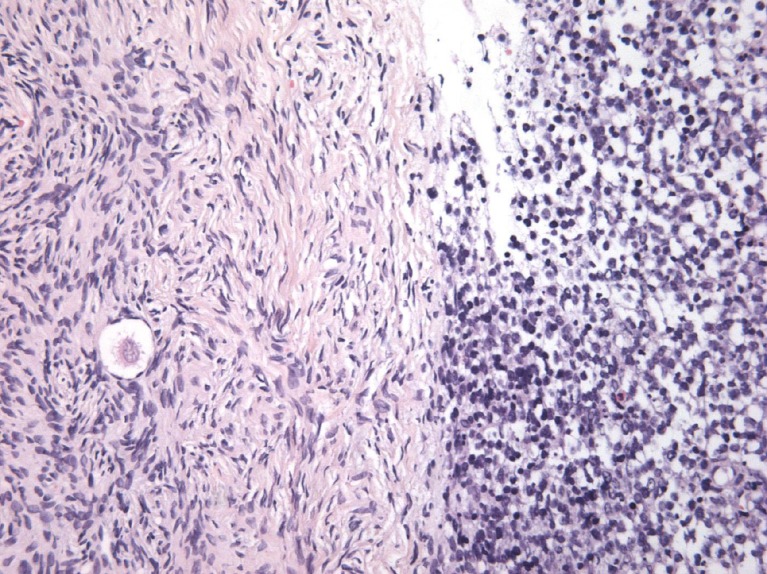

Thirty-two small pieces were excised from the removed ovary in order to be cryopreserved. Four of them were isolated for subsequent histological analysis as a routine protocol in our department. All of this collected tissue showed evidence of ovarian involvement by lymphoma cells, despite normal macroscopic aspect (Fig. 2). Final histological results of the lymph node were obtained the day after cryopreservation and were consistent with the diagnosis of Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma (PMBCL).

Fig. 2.

Massive involvement of NHL cells in the ovarian cortex

After the four R-CVAD cycles, the patient received a BEAM protocol (BCNU 300 mg/m2, etoposide 100 mg/m2, cytarabine 200 mg/m2, melphalan 140 mg/m2, procarbazine 100 mg/m2, prednisone 40 mg/m2) prior to perform a stem-cell transplantation.

Two years after the end of treatment, the patient remains in remission. She recovered only three menstrual cycles during the last two years. AMH levels remained undetectable with high FSH levels. Fortunately, despite this poor reproductive prognosis, she conceived spontaneously and delivered a healthy baby.

Discussion

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation is theoretically the most efficient way of preserving thousands of ovarian follicles at one time in term of pregnancies. This technique of fertility preservation remains the only option for prepubertal females and for those women who cannot delay their cancer treatment in order to undergo ovarian stimulation for egg retrieval. Nevertheless, despite these positive aspects and the increasing number of live births after successful ovarian tissue transplantation, ovarian cryopreservation still should be considered experimental [17]. Indeed, there is concern regarding the possible presence of malignant cells in the ovarian tissue, which could lead to recurrence of the primary disease after reimplantation [7, 10, 18, 19]. Hence, it remains difficult at present to establish the imbalance between the real chances of pregnancy this technique can offer, versus the risk of mainly reintroducing the disease and also reducing the ovarian reserve.

HL and NHL are frequent indications for ovarian tissue freezing and are commonly considered at minimal risk of ovarian involvement [18, 20, 21]. However, caution is required due to the results of two studies [22, 23]. On one hand, Shaw et al. reported that ovarian tissue collected from AKR mice with lymphoma could transfer the disease to healthy recipient animals [22]. And on the other, Kyono et al., in a study aiming to evaluate the feasibility of auto-transplantation based on the analysis of 5 571 autopsy findings of young females (but dead from malignant diseases!), showed 4.3 % and 9.8 % of ovarian involvement by HL or NHL cells, respectively [23]. Few experimental studies have tested the human ovarian tissue from both HL or NHL and failed to show evidence of ovarian involvement by lymphoma cells [18, 20, 24, 25]. To date, 15 auto-transplantations have been reported in HL patients and 6 in NHL without any disease recurrence, knowing that the follow-up after auto-transplantation in one of the HL patients is now up to 8 years [19, 26–34]. Nevertheless, a recent case-report showed an ovarian involvement in the histologic examination of ovarian cortex pieces in a stage III HL [15]. The transvaginal ultra-sonographic exam and the Positron Emission Tomography with 18 FDG performed before the surgery didn’t detect any abnormality in this case.

In the current case-report, the patient was diagnosed a rare subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, whose frequency is estimated at 2-5 % of non-Hodgkin lymphoma [35]. The epidemiological features are at an early age and a sex ratio to 2 in favor of females, with no specific identified risk factors so far. Compression of large mediastinal vessels is common in patients with PMBCL [36]. Although ovarian locations represent a rare event in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, it seems that extra nodal localisations are more frequent in PMBCL subtype. Caution is thus required before the auto-transplantation of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue in this context. In a recent publication, according to recent reports, Dolmans et al. adapted the classification of Sonmezer and Oktay [21] by recategorizing NHL from low to moderate risk of ovarian involvement [19]. Indeed, this Belgian team detected malignant cells by histologic evaluation in 2 patients from 32 (6 %) with NHL [19]. The real presence of malignant cells in the ovarian tissue is surely under-estimated because the histologic evaluation and immunophenotyping B-cells are well-recognized as not being sufficiently sensitive.

In our case report, the Positron Emission Tomography with 18 FDG highlighted a slight uptake in the pelvic area that we have not taken into account in our decision of ovarian cryopreservation. Indeed, it could have been an a-specific uptake related to a functional cyst. As we didn’t have time to harvest mature oocytes, the ovarian cryopreservation was the only option for this patient. The question is then asked as whether it would be better to perform the cryopreservation after first lines of chemotherapy in order to decrease the risk of cancer recurrence after auto-transplantation. Ovarian cryopreservation aims to preserve primordial follicles, which are presumably less damaged by chemotherapy than growing follicles [4]. Meirow et al. reported a live birth after autotransplantation of ovarian tissue that had been cryopreserved after a first line of chemotherapy [37]. But we have to keep in mind that chemotherapy regimens damage the ovaries through apoptotic effects but also through cortical fibrosis and blood microvessels injury [38]. One of the consequences of this vascular toxicity is that the duration of the restored ovarian function after auto-transplantation could be shorter (1–2 years) when patients had undergone chemotherapy before cryopreservation [38].

New developments for the reutilization of the harvested ovarian tissue, all experimental, are emerging. One approach is the re-implantation of isolated follicles from the ovarian tissue [39]. Indeed, isolated human preantral follicles can survive and grow in vitro, that represents a lot of hope for the future [40–43]. Another approach is the In Vitro Maturation (IVM) of immature oocytes [44–46]. Last, combined procedure, meaning the combination of IVM of immature oocytes and ovarian tissue cryopreservation on the same day, could be a promising strategy too [12, 44–46].

In conclusion, recent data regarding the potential ovarian involvement in HL and NHL urge caution when a reimplantation of ovarian tissue is planned. This case report stresses the need to discuss it with patients, for both the decision of ovarian removal for cryopreservation and the decision of auto-transplantation. It is crucial to make sure that women and reproductive doctors will be obviously both helped in their decision by a multidisciplinary approach [47].

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule Recent data regarding the potential ovarian involvement by lymphoma cells urge caution when a reimplantation of ovarian tissue is planed. Patients have to be rigorously informed about this risk before the decision of ovarian removal or auto-transplantation.

References

- 1.Wallace WHB, Anderson RA, Irvine DS. Fertility preservation for young patients with cancer: who is at risk and what can be offered? Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):209–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan S, Anderson RA, Gourley C, Wallace WH, Spears N. How do chemotherapeutic agents damage the ovary? Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(5):525–35. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meirow D, Nugent D. The effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7(6):535–43. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meirow D, Dor J, Kaufman B, Shrim A, Rabinovici J, Schiff E, et al. Cortical fibrosis and blood-vessels damage in human ovaries exposed to chemotherapy. Potential mechanisms of ovarian injury. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1626–33. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jadoul P, Anckaert E, Dewandeleer A, Steffens M, Dolmans M-M, Vermylen C. Clinical and biologic evaluation of ovarian function in women treated by bone marrow transplantation for various indications during childhood or adolescence. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(1):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jadoul P, Kim SS. ISFP Practice Committee. Fertility considerations in young women with hematological malignancies. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(6):479–87. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9792-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnez J, Dolmans M-M. Preservation of fertility in females with haematological malignancy. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(2):175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salooja N, Szydlo RM, Socie G, Rio B, Chatterjee R, Ljungman P, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after peripheral blood or bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9278):271–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2500–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt KT, Andersen CY. ISFP Practice Committee. Recommendations for fertility preservation in patients with lymphomas. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(6):473–7. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9787-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson RA, Wallace WHB, Baird DT. Ovarian cryopreservation for fertility preservation: indications and outcomes. Reproduction. 2008;136(6):681–9. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung K, Donnez J, Ginsburg E, Meirow D. Emergency IVF versus ovarian tissue cryopreservation: decision making in fertility preservation for female cancer patients. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1534–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnez J, Dolmans M-M, Pellicer A, Diaz-Garcia C, Sanchez Serrano M, Schmidt KT, et al. Restoration of ovarian activity and pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue: a review of 60 cases of reimplantation. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demeestere I, Simon P, Emiliani S, Delbaere A, Englert Y. Orthotopic and heterotopic ovarian tissue transplantation. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(6):649–65. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittinger SE, Nazaretian SP, Gook DA, Parmar C, Harrup RA, Stern CJ. Detection of Hodgkin lymphoma within ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):803. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decanter C, Morschhauser F, Pigny P, Lefebvre C, Gallo C, Dewailly D. Anti-Müllerian hormone follow-up in young women treated by chemotherapy for lymphoma: preliminary results. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20(2):280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(5):1214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meirow D, Hardan I, Dor J, Fridman E, Elizur S, Ra’anani H, et al. Searching for evidence of disease and malignant cell contamination in ovarian tissue stored from hematologic cancer patients. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(5):1007–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolmans M-M, Luyckx V, Donnez J, Andersen CY, Greve T. Risk of transferring malignant cells with transplanted frozen-thawed ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meirow D, Ben Yehuda D, Prus D, Poliack A, Schenker JG, Rachmilewitz EA, et al. Ovarian tissue banking in patients with Hodgkin’s disease: is it safe? Fertil Steril. 1998;69(6):996–8. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonmezer M, Oktay K. Fertility preservation in female patients. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(3):251–66. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw JM, Bowles J, Koopman P, Wood EC, Trounson AO. Fresh and cryopreserved ovarian tissue samples from donors with lymphoma transmit the cancer to graft recipients. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(8):1668–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyono K, Doshida M, Toya M, Sato Y, Akahira J, Sasano H. Potential indications for ovarian autotransplantation based on the analysis of 5,571 autopsy findings of females under the age of 40 in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2429–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seshadri T, Gook D, Lade S, Spencer A, Grigg A, Tiedemann K, et al. Lack of evidence of disease contamination in ovarian tissue harvested for cryopreservation from patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and analysis of factors predictive of oocyte yield. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(7):1007–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SS, Radford J, Harris M, Varley J, Rutherford AJ, Lieberman B, et al. Ovarian tissue harvested from lymphoma patients to preserve fertility may be safe for autotransplantation. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(10):2056–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radford JA, Lieberman BA, Brison DR, Smith AR, Critchlow JD, Russell SA, et al. Orthotopic reimplantation of cryopreserved ovarian cortical strips after high-dose chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1172–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04335-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnez J, Dolmans MM, Demylle D, Jadoul P, Pirard C, Squifflet J, et al. Livebirth after orthotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Lancet. 2004;364(9443):1405–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17222-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt KLT, Andersen CY, Loft A, Byskov AG, Ernst E, Andersen AN. Follow-up of ovarian function post-chemotherapy following ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(12):3539–46. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demeestere I, Simon P, Buxant F, Robin V, Fernandez SA, Centner J, et al. Ovarian function and spontaneous pregnancy after combined heterotopic and orthotopic cryopreserved ovarian tissue transplantation in a patient previously treated with bone marrow transplantation: case report. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(8):2010–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demeestere I, Simon P, Emiliani S, Delbaere A, Englert Y. Fertility preservation: successful transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a young patient previously treated for Hodgkin’s disease. The oncologist. 2007;12(12):1437–42. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolmans M-M, Donnez J, Camboni A, Demylle D, Amorim C, Van Langendonckt A, et al. IVF outcome in patients with orthotopically transplanted ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(11):2778–87. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt KT, Rosendahl M, Ernst E, Loft A, Andersen AN, Dueholm M, et al. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in 12 women with chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian failure: the Danish experience. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen CY, Rosendahl M, Byskov AG, Loft A, Ottosen C, Dueholm M, et al. Two successful pregnancies following autotransplantation of frozen/thawed ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(10):2266–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dittrich R, Lotz L, Keck G, Hoffmann I, Mueller A, Beckmann MW, et al. Live birth after ovarian tissue autotransplantation following overnight transportation before cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):387–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faris JE, LaCasce AS. Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol HO. 2009;7(2):125–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson PWM, Davies AJ. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Educ Program Am Soc Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;349–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Meirow D, Levron J, Eldar-Geva T, Hardan I, Fridman E, Zalel Y, et al. Pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a patient with ovarian failure after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):318–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc055237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meirow D, Biederman H, Anderson RA, Wallace WHB. Toxicity of chemotherapy and radiation on female reproduction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(4):727–39. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181f96b54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smitz J, Dolmans MM, Donnez J, Fortune JE, Hovatta O, Jewgenow K, et al. Current achievements and future research directions in ovarian tissue culture, in vitro follicle development and transplantation: implications for fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):395–414. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanacker J, Luyckx V, Amorim C, Dolmans M-M, Van Langendonckt A, Donnez J. Should we isolate human preantral follicles before or after cryopreservation of ovarian tissue? Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1363–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amorim CA, Van Langendonckt A, David A, Dolmans M-M, Donnez J. Survival of human pre-antral follicles after cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, follicular isolation and in vitro culture in a calcium alginate matrix. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(1):92–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hovatta O. Cryopreservation and culture of human ovarian cortical tissue containing early follicles. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113(Suppl 1):S50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telfer EE, McLaughlin M. In vitro development of ovarian follicles. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(1):15–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berwanger AL, Finet A, El Hachem H, le Parco S, Hesters L, Grynberg M. New trends in female fertility preservation: in vitro maturation of oocytes. Future Oncol. 2012;8(12):1567–73. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grynberg M, El Hachem H, de Bantel A, Benard J, le Parco S, Fanchin R. In vitro maturation of oocytes: uncommon indications. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chian R-C, Uzelac PS, Nargund G. In vitro maturation of human immature oocytes for fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Ziegler D, Streuli I, Vasilopoulos I, Decanter C, This P, Chapron C. Cancer and fecundity issues mandate a multidisciplinary approach. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):691–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]