Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the dual effects of superovulation on the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring in mice

Method

The mice were superovaluted. The relative uterine weight, ERα protein expression, and endocrine activity of female offspring (F1 generation and F2 generation) were measured. Furthermore, proliferative lesion of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring (F1 generation and F2 generation) was assessed by histopathologic examinations.

Results

There were no significant differences in relative uterine weight, ERα protein expression, incidence of proliferative lesion in mammary glands, and incidence of atypical hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, and squamous metaplasia in uterine among the offspring (F1 generation and F2 generation) in each group. Likewise, there were no significant intergroup differences in the serum levels of sex related hormones.

Conclusions

No significant alterations were found in the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring in mice produced by superovaluted oocytes compared with those of naturally conceived offspring.

Keywords: Superovulation, Female, Offspring, Endocrine activity, Carcinogenesis

Introduction

The use of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) for the treatment of human subfertility/infertility contributes 2-4 % of all children born in developed countries [1]. However, the safety of these technologies has yet to be fully evaluated. Accumulating evidence indicates that ART children are at increased risk for intrauterine growth retardation, premature birth, low birth weight, early adulthood clinical depression, binge drinking, and genomic imprinting disorders [2–4].

Superovulation, or ovarian stimulation, is an ART procedure that enables increased oocyte production. It has been common practice to treat infertility in humans. Gonadotrophins are commonly used for superovulation in animals and in humans, for example to increase the number of oocytes that can be retrieved for in vitro fertilization, thus improving the overall chance for successful fertilization and pregnancy. The use of high dose of gonadotrophins has recently caused much debate surrounding their effects on oocyte maturation [5, 6]. Because imprint acquisition has been shown to occur relatively late in oogenesis, the establishment of these imprints may be susceptible to exogenous hormone treatments [7–10].

It is becoming increasingly obvious that the period of time during fetal development is an important factor in the life-long health of the individual [11]. An adverse in utero environment may profoundly influence an individual’s susceptibility to disease late in childhood, adolescence and adult life [12]. Data suggest xenoestrogen exposure during pregnancy alters hormone programming so that the uterus responds abnormally to estrogen later in life [13]. It was reported that prenatal or developmental exposure to bisphenol A delayed the development of the male mammary gland and increased susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis [14, 15]. Females exposure in utero to the synthetic estrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), commonly referred to as “DES daughters”, have increased risks of vaginal cancer after puberty [16, 17]. Furthermore, neonatal exposure to DES in rats has been reported to affect mammary carcinogenesis [18]. Whether in utero exposure to estrogen excess induced by superovulation exerts long-term effects even transgenerational effects on the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring or not? Since the first IVF-conceived baby was born in 1978, it is difficult to carry out large longitudinal studies, we therefore employ animal model to preliminarily testify the postulation.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice at 8–9 wk of age were used for ovarian stimulation. Male C57BL/6 mice at 30 wk of age were used for mating. Mice were kept under pathogen-free condition with a 30-60 % humidity, a temperature ranging from 21 to 24 °C, a light cycle of 12 h light: 12 h darkness, and were given free access to sterile food and water. The Animal Care Committee of Shandong University approved all the experimental procedures carried out in the study.

Ovarian stimulation

The protocol was carried out as described previously [19]. The female mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 50 per group): controlled group and ovarian stimulation group (stimulation with 10 IU Pregnant Mare’s Serum Gonadotropin, Intervet Canada). Administered of Pregnant Mare’s Serum Gonadotropin was followed by the same dose of Human Serum Chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, Intervet Canada) 40–44 h later. Female were mated with males, and pregnancy was determined by the presence of a vaginal plug the following morning. The offspring of F0 generation were F1 generation, and the offspring of F1 generation were F2 generation. Female F1 generation and F2 generation produced by superovaluted oocytes as well as the naturally conceived female offspring were used for following studies. The experiments were performed when the offspring were 10 months old; therefore, the animals are referred to as adult.

Immunohistochemistry

Female offspring (n = 30 per group) was euthanized on estrus by CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation, and body and uterine weights were determined. The relative uterine weight (uterine weight/body weight) was calculated. Uterines (with fluid) were fixed in formaldehyde in PBS (10 %), dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in Paraplast. To perform the immunohistochemistry for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα - 6 F11:sc-56836, Santa Cruz, 1:1000), biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:100) and normal horse serum were used.

Uterine transverse sections (6 μm) were dewaxed using toluene and hydrated using decreasing concentrations of ethanol, followed by antigen recovery with citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0 - microwave, 650 watt, high temperature, 3 min × 5 min) [20]. After PBS wash, the slides were incubated for 10 min with blocking solution to avoid unspecific reactions. Then, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody.

The sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with appropriate secondary biotinylated antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Then, slides were incubated with ABC solution (1:400) for 1 h at room temperature (VECTASTAIN ABC KIT, PK 4000, Vector laboratories, Inc.) to evidence the immunocomplex formed by secondary antibody linked to the primary antibody.

Peroxidase activity was revealed using diaminobenzidine solution (DAB) (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 10 min at room temperature. The sections were washed and counterstained with toluidine blue, dehydrated by applying increasing concentrations of ethanol, cleared by xylene and coverslipped with Permount. For the steroid receptors, sections were analyzed under light microscope and the evaluation was performed by semi-quantitative scale, according to intensity of staining at luminal and glandular epithelium, stroma and myometrium.

The result of immunohistochemical staining for ERα was evaluated semiquantitatively based on Guerra et al. [21]: overstained (diffusion of the reaction product and/or non-specific background), strong (black or dark brown), light (medium brown), very light staining (usually restricted to a smaller number of stained cells) or no visible staining.

Histopathologic assessment of proliferative lesions in the uterus and mammary glands

The organs (n = 30 per group) were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin. Tissues were routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopatologic examination. Preneoplastic lesions were classified into three degrees of atypical hyperplasia (slight, moderate, or severe) and adenocarcinomas according to a previous study [22]. Slight/moderate endometrial hyperplasias refers increased numbers of glands with slightly/moderately atypical cells in focal and/or diffuse areas of the endometrium. Severe hyperplasias were composed of irregular proliferation of atypical glands, which were characterized by crowding, stratification, and irregularity of cells with back-to-back disposition. Lesions composed of glandular-structured epithelial cells with atypia showing invasive proliferation to the muscle layer or serosa were diagnosed as endometrial adenocarcinomas. Histological slides were observed blindly, under a light microscope, by two independent veterinary pathologists.

Hormone assays

Serum samples (n = 30 per group) obtained after decapitation were stored at −80 °C until assay. The serum concentration of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), inhibin, estradiol-17β (E2), progesterone (P4), and prolactin (PRL) were determined using double-antibody radioimmunoassay and 125I-labeled radio-ligands. National Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) radioimmunoassay kits were used for rat FSH, LH, and PRL (NIAMDD, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) with anti-rat LH-S-11, anti-rat FSH-S-11 and anti-rat PRL-S-9 sera, as described previously [23]. P4 and E2 were measured using the anti-sera against P4 (GDN 337) and E2 (GDN 244) as described by Takahashi et al. [24]. Iodinated 32-kDa bovine inhibin and a rabbit antibody againstbovine inbibin (TNDH-1) were used for measurement of immunoreactive serum inhibin, as described previously [25].

Statistical analysis

The proliferative lesions of uterus and mammary glands in each group were compared using chi-square test analysis. The mean relative uterine weight and the serum levels of sex related hormones were analyzed first using Bartlett’s test (significance level: 1 %) to examine homogeneous of variance. If the variance was determined to be homogeneous, a Dennett’s test (significance level: 5 %, indices are shown at both P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, two tailed test) was conducted. However, if the variance was heterogeneous, a Dennett’s multiple comparison test (significance level: 5 %, indices are shown at both P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, two = tailed) was applied. Values were considered significant when P < 0.05. SAS version 8.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Uterus weight and ERα protein expression

No significant differences were found in the mean relative uterine weight and ERα protein expression of F1 generation between ovarian stimulation group and naturally conceived group (P > 0.05). Likewise, there were no significant differences in the mean relative uterine weight and ERα protein expression of F2 generation between ovarian stimulation group and naturally conceived group (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The relative uterine weight (uterine weight/body weight), ERα protein expression, and histopathologic findings of the uterus observed in mice

| F1 generation of control group | F1 generation of superovulation group | F2 generation of control group | F2 generation of superovulation group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| The relative uterine weight (%) | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.86 ± 0.08 |

| ERα intensity | 134.6 ± 18.9 | 132.8 ± 16.4 | 136.4 ± 14.2 | 138.3 ± 15.2 |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 12 (24 %) | 15 (30 %) | 14 (28 %) | 16 (32 %) |

| Slight | 9 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Moderate | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Severe | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cystic endometrial hyperplasia | 8 (16 %) | 10 (20 %) | 9 (18 %) | 12 (24 %) |

| adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Squamous metaplasia | 4 (8 %) | 5 (10 %) | 3 (6 %) | 4 (8 %) |

| Adenomysis | 5 (8 %) | 2 (4 %)* | 6 (12 %) | 4 (8 %) |

| Disappearance of lumina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*: Significantly different from F1 generation of control group

Histopathologic assessment of proliferative lesions in the uterus and mammary glands

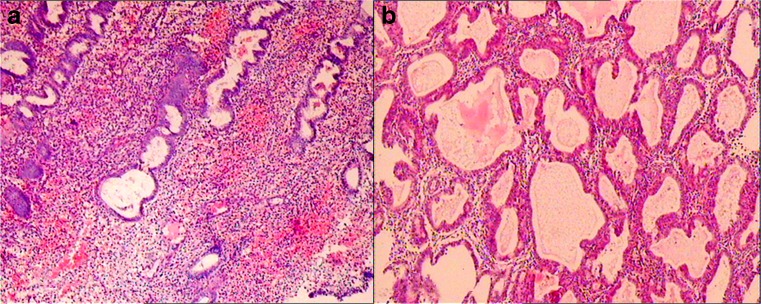

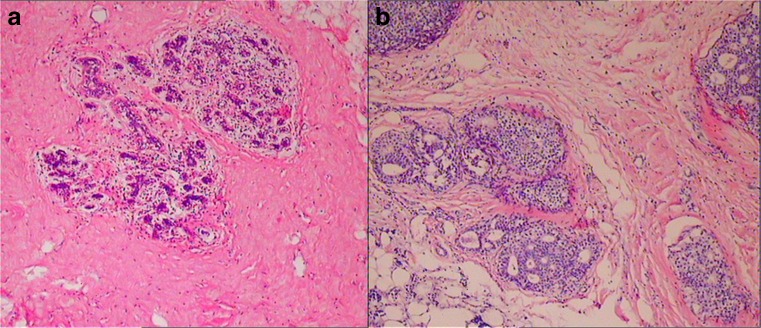

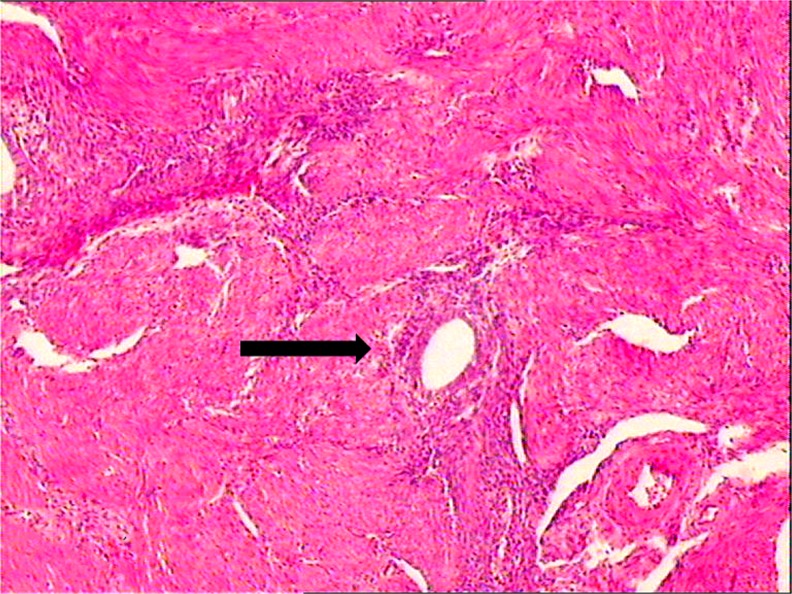

No significant differences were observed in the incidence of uterine atypical hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, and squamous metaplasia of F1 generation between control group and superovulation group (P > 0.05). There was a significant decrease in the incidence of adenomysis of F1 generation produced by superovaluted oocytes (P < 0.05).

There were no significant differences in the incidence of uterine atypical hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, squamous metaplasia, and adenomysis of F2 generation in control group in comparison to those in superovulation group (P > 0.05). In the mammary glands, although increased milk secretion was frequently observed in F1 generation produced by superovulated oocytes, the incidence and severity were similar among the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2) (Figs. 1-2 and 3).

Table 2.

Histopathologic findings of the mammary glands observed in mice

| F1 generation of control group | F1 generation of superovulation group | F2 generation of control group | F2 generation of superovulation group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Increased milk secretion | 14 (28 %) | 20 (40 %)* | 13 (26 %) | 15 (30 %) |

| Slight | 12 | 14 | 10 | 12 |

| Moderate | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Severe | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 2 (4 %) | 3 (6 %) | 1 (2 %) | 2 (4 %) |

| Lobular hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | 1 (2 %) | 0 |

| Ductal hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2 %) |

| Adenoma | 0 | 1 (2 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Fibroadenoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxyphilic cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*: Significantly different from F1 generation of control group

Fig. 1.

A Normal morphologic endometrial. B Endometrial hyperplasias were composed of irregular proliferation of atypical glands, which were characterized by crowding, stratification, and irregularity of cells with back-to-back disposition (magnification × 200)

Fig. 2.

A Normal morphologic mammary glands. B: Breast ductal hyperplasias were composed of irregular proliferation of atypical glands, which were characterized by crowding, stratification, and irregularity of cells with back-to-back disposition (magnification × 200)

Fig. 3.

Endometrial in the uterine muscle (→) (magnification × 200)

Hormone assays

There were no significant intergroup differences in the serum levels of sex related hormones of the F1 generation in control group in comparison to that in superovulation group (P > 0.05). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the serum levels of sex related hormones of F2 generation between control group and superovulation group (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Serum level of sex-related hormones at 10 months of age

| F1 generation of control group | F1 generation of superovulation group | F2 generation of control group | F2 generation of superovulation group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 75.8 ± 5.8 | 73.1 ± 6.1 | 72.9 ± 5.3 | 75.4 ± 4.9 |

| P4 (ng/ml) | 15.6 ± 0.9 | 17.1 ± 1.1 | 16.8 ± 1.1 | 16.3 ± 1.4 |

| FSH (ng/ml) | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| LH (pg/ml) | 38.6 ± 2.1 | 37.4 ± 2.6 | 40.1 ± 3.9 | 41.8 ± 3.1 |

| PRL (ng/ml) | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Inhibin (ng/ml) | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

Discussion

A mismatch between the early life environments may lead to inappropriate early life-course epigenomic changes that manifest in late life as increased vulnerability to disease [26]. There are now increasing data that these responses are, at least partially, underpinned by epigenetic mechanisms. Data from mouse experiments and the in vitro production of livestock provide strong evidence that imprint establishment in late oocyte stages and reprogramming of germline genomes for somatic development after fertilization are vulnerable to environmental cues [4]. For example, individuals who were conceived during a famine period showed methylation changes in the imprinted growth factor IGF2 and other medically relevant genes more than 60 years late [27]. At the same time, these individuals suffered from increased risks for obesity, coronary artery disease, accelerated cognitive aging, and schizophrenia [28]. Prenatal exposure to androgen excess can lead to, as adults, disrupted ovarian cycles and abnormalities of early follicle development that mimic those observed in women with polycystic ovary syndrome [29]. Bosquiazzo et al. reported that perinatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol altered the functional differentiation of the adult rat uterus [30]. Moreover, neonatal exposure to estrogen might be a risk factor for uterine carcinogenesis [24].

In this study, there were no significant differences in relative uterine weight and ERα protein expression among the offspring in each group. Likewise, no statistical differences were noted in the incidence of uterine atypical hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, and squamous metaplasia among the groups. It is worth mentioning that there was a significant decrease in the incidence of adenomysis of F1 generation produced by superovaluted oocytes. In the mammary glands, although increased milk secretion was frequently observed in F1 generation produced by superovulated oocytes, the incidence and severity were similar among the groups. Therefore, we concluded that superovulation did not increase tendency toward severity of proliferative lesion in uterine and mammary glands of offspring produced by superovaluted oocytes in mice.

Endocrine activity is regarded as a very useful indicator of delayed adverse effects on the female reproductive tract [24]. The results of this study indicated that there were no significant intergroup differences in the serum levels of sex related hormones.

Transgenerational effects results from a mother’s exposure and are inherited through successive generations in the absence of direct exposure of the offspring. Such environmental factors can affect spermatogenesis at the level of germ and stertoli cells and the composition of seminal fluid [31], in some cases lasting dozens of generations [32]. The results of this study preliminarily proved that superovulation does not exert transgenerational effects on the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring in mice. Nevertheless, Sato et al. found that individual human oocytes from women undergoing multiple hormone stimulations possessed aberrant imprinting at both the PEG1 and H19 loci [33]. Market-Velker et al. reported that superovulation alone affected genomic imprinting in blastocyst-stage embryos at four imprinted genes (Snrpn, Kcnq1ot1, Peg3, and H19) in a hormone dosage-dependent manner [19]. So, we suggest large-scale, multi-center follow-up studies of the long-term effect of superovulation on the human offspring be performed.

In summary, the data of this animal experiment preliminarily prove that no significant alterations were found in the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of uterine and mammary glands of female offspring in mice produced by superovaluted oocytes compared with those of naturally conceived offspring.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mei Wang for the valuable comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule

Effects of superovulation on the endocrine activity and susceptibility to carcinogenesis of offspring

References

- 1.Blyth E. Below population replacement fertility rates: Can assisted reproductive technology (ART) help reverse the trend? Asian Pacific J Reprod. 2013;2:151–8. doi: 10.1016/S2305-0500(13)60137-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart R, Norman RJ. The longer-term health outcomes for children born as a result of IVF treatment. Part II–Mental health and development outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:244–55. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle P, Beral V, Maconochie N. Preterm delivery, low birthweight and small-for-gestational-age in live-born singleton babies resulting from in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:425–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anckaert E, Rycke MD, Smitz J. Culture of oocytes and risk of imprinting defects. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:52–66. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Auwera I D,Hooghe T. Superovulation of female mice delays embryonic and fetal development. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1237–43 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Krisher RL. The effect of oocyte quality on development. J Anim Sci. 2004;82 (E-Suppl):E14–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lucifero D, Mann MR, Bartolomei MS, Trasler JM. Gene-specific timing and epigenetic memory in oocyte imprinting. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:839–49. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiura H, Obata Y, Komiyama J, Shirai M, Kono T. Oocyte growth-dependent progression of maternal imprinting in mice. Genes Cells. 2006;11:353–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anckaert E, Adriaenssens T, Romero S, Dremier S, Smitz J. Unaltered imprinting establishment of key imprinted genes in mouse oocytes after in vitro follicles culture under variable follicle-stimulating hormone exposure. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:541–8. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082619ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denomme MM, Zhang L, Mann MR. Embryonic imprinting perturbations do not originate from superovulation-induced defects in DNA methylation acquisition. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:734–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suter MA, Aaqaard K. What changes in DNA methylation take place in individuals exposed to maternal smoking in utero? Epigenomic. 2012;4:115–8. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newbold RR, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Haseman J. Developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) alters uterine response to estrogens in prepubescent mice: low versus high dose effects. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass L, Durando M, Altamirano GA, et al. Prenatal Bisphenol A exposure delays the development of the male rat mammary gland. Reprod Toxicol. 2004 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ho SM, Tang WY, de Frausto JB, Prins GS. Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5624–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbst AL, Anderson D. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix secondary to intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Semin Surg Oncol. 1990;6:343–6. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980060609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swan SH. Intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol: long-term effects in humans. APMIS. 2000;108:793–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2000.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi H, Umekita Y, Souda M, Gejima K, Kawashima H, et al. Effects of neonatally administered high-dose diethylstilbestrol on the induction of mammary tumors induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz [a] anthracene in female rats. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:142–50. doi: 10.1354/vp.46-1-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Market-Velker BA, Zhang L, Magri LS, Bonvissuto AC, Mann MR. Dual effects of superovulation: loss of maternal and paternal imprinted methylation in a dose-dependent manner. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:36–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaton AJ, Ochando F, Painchaud MH. Use of microwaves of enhancing or restoring antigens before immunohistochemical staining. Ann Pathol. 1993;13:188–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerra MT, Sanabria M, Grossman G, Petrusz P, Kempinas WG. Excess androgen during perinatal life alters steroid receptor expression, apoptosis, and cell proliferation in the uteri of the offspring. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;40:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida M, Takahashi M, Inoue K, Hayashi S, Maekawa A, et al. Delayed adverse effects of neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol and their dose dependency in female rats. Toxicol Pathol. 2011;39:823–34. doi: 10.1177/0192623311413785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taya K, Mizokawa T, Matsui T, Sasamoto S. Induction of superovulation in prepubertal female rats by anterior pituitary transplants. J Reprod Fertil. 1983;69:265–70. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0690265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi M, Inoue K, Morikawa T, Matsuo S, Hayashi S, et al. Delayed effects of neonatal exposure to 17alpha-ethynylestradiol on the estrous cycle and uterine carcinogenesis in Wistar Hannover GALAS rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;40:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamada T, Watanabe G, Kokuho T, Taya K, Sasamoto S, et al. Radioimmunoassay of inhibin in various mammals. J Endocrinol. 1989;122:697–704. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1220697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low FM, Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental plasticity and epigenetic mechanisms underpinning metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Epigenomics. 2011;3:279–94. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De rooij SR, Wouters H, Yonker Jf, Painyer RC, Roseboom J. Prenatal undernutrition and cognitive function in late adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16881–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Franks S. Animal models and the developmental origins of polycystic ovary syndrome: increasing evidence for the role of androgens in programming reproductive and metabolic dysfunction. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2536–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosquiazzo VL, Vigezzi L, Muñoz-de-Toro M, Luque EH. Preinatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol alters the functional differentiation of the adult rat uterus. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, et al. Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals. Cell. 2010;143:1084–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato A, Otsu E, Negishi H, Utsunomiya T, Arima T. Aberrant DNA methylation of imprintedloci in superovulated oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:26–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]