Abstract

Danggui Buxue Tang (DBT), a herbal decoction containing Astragali Radix (AR) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (ASR), has been used in treating menopausal irregularity in women for more than 800 years in China. Pharmacological results showed that DBT exhibited significant estrogenic properties in vitro, which therefore suggested that DBT could activate the nuclear estrogen receptors. Here, we assessed the estrogenic properties of DBT in an ovariectomized in vivo rat model: DBT was applied to the ovariectomized rats for 3 days. The application of DBT did not alter the weight of uterus and liver, as well as the transcript expression of the proliferation markers including the estrogen receptors α and β. However, DBT stimulated the transcript expression of the estrogen responsive genes. In addition, the inductive role of DBT on the expression of members of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor family in uterus and liver of ovariectomized rats was confirmed. These responses of DBT however were clearly distinct from the response pattern detectable here for 17β-estradiol. Therefore, DBT exhibited weak, but significant, estrogenic properties in vivo; however, some of its activities were independent of the estrogen receptor. Thus, DBT could be an exciting Chinese herbal decoction for an alternative treatment of hormone replacement therapy for women in menopause without subsequent estrogenic side effects.

1. Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) have been used as medicines or health food supplements in China for over thousand years. Historically, TCMs are prepared as decoctions by a unique methodology with specific combinations of different herbs as a formula. Among thousands of herbal formulae, Danggui Buxue Tang (DBT) is a simple herbal decoction that is composed of two herbs. DBT was first described in Neiwaishang Bianhuo Lun by Li Dongyuan in China in AD 1247. Li described that the DBT formula should include 10 qian of Astragali Radix (AR), roots of Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge or Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bungevar. mongholicus (Bunge) P.K. Hsiao, and two qian of Angelicae Sinensis Radix (ASR), roots of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. One qian equals about 3 grams. DBT is prescribed for women in China as a remedy for menopausal symptoms, which improves their health by raising the “Qi” (vital energy) and nourishing the “blood” (body circulation).

Women in menopause suffer from hot flushes, sweating, anxiety, and mood swings, as well as from an increased risk for many health problems, such as loss of bone density mass (osteoporosis) and cardiovascular disease. These problems are largely due to the deficiency of ovarian hormones, especially estrogens [1]. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had been used to alleviate menopausal symptoms for many years, but this treatment was associated with side effects, that is, an increased risk of breast cancer, heart attacks, and strokes [2]. In view of these clinical risks, extensive efforts have been devoted to searching or developing new drugs that would yield the benefits of hormone therapy but with minimal risk [3]. TCM, containing thousands of medicinal herbs, is a promising resource that could provide a perfect solution [4]. Indeed, some of the herbal products showed a pronounced efficacy for menopausal symptoms and as a consequence were widely used by women to relieve their menopausal symptoms, for example, DBT [5–8]. In vitro experiments with mammary gland [6] and bone [9] derived cells suggested that at least some of the effectiveness of DBT is mediated through estrogen receptor- (ER-) dependent mechanisms. In order to support these observations in vivo, DBT was tested in the ovariectomized Wistar rat model for potential estrogenic properties. Since DBT is a decoction that traditionally is consumed as a tea, animals were supplemented by DBT through the drinking water. Taking this approach, we performed a three-day uterotrophic assay for revealing responses relevant to contribute to the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of action of DBT, including organ weights and regulation of gene expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and DBT Preparation

Three-year-old AR deriving from the roots of A. membranaceus var. mongholicus was collected from Shanxi province [10], and 2-year-old ASR of A. sinensis was from Minxian in Gansu province [11]. These plant materials had been morphologically authenticated by Dr. Tina Dong, during the field collection. The corresponding vouchers as forms of whole plants, voucher # 02-9-1 for ASR and voucher # 02-10-4 for AR, were deposited in the Center for Chinese Medicine, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. 17β-Estradiol (E2) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany). 250 g of sliced AR and 50 g of sliced ASR were mixed (the ratio is 5 : 1) and then boiled in 2,400 mL (w : v = 1 : 8) of water for 2 hours, and then the decoction was filtered. The residues were boiled in 1,800 mL (w : v = 1 : 6) water for 1 hour. The combined extracts were dried under vacuum and stored at −20°C. This extraction, following the ancient preparation, was shown to be the best extracting condition [12]. Two chemical markers in AR (calycosin and formononetin) and two others in ASR (ferulic acid and ligustilide) were used to standardize the chemical property of DBT. The standardized DBT should contain no less than 0.186 mg calycosin, 0.155 mg formononetin, 0.351 mg ferulic acid, and 0.204 mg ligustilide per one g dried weight of DBT, as reported previously [5, 6, 8].

2.2. Animals

Juvenile female Wistar rats (130 ± 15 g) were obtained from Harlan Winkelmann (Borchen, Germany) and were maintained under controlled conditions of temperature (20°C ± 1, relative humidity 50–80%) and illumination (12 hours light, 12 hours dark). All rats had free access to standard rat diet (SSniff R10-Diet, SSniff GmbH, Soest, Germany) and water. All animal husbandry and handling conditions were according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines in Germany.

2.3. Uterotrophic Assay

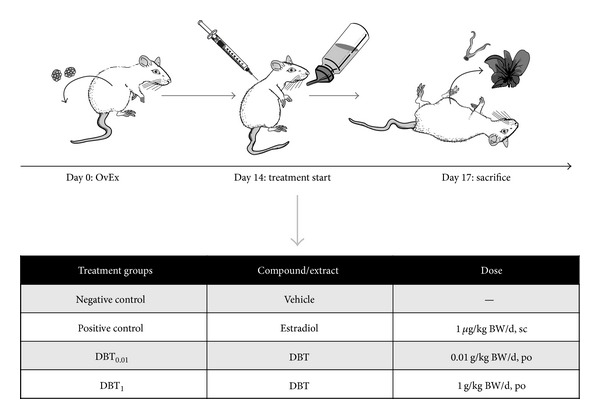

The estrogenicity was tested in the 3-day assay in ovariectomized rats according to the OECD guideline 440 [13]. The experimental procedures are schematically summarized in Figure 1. Briefly, following ovariectomy and 14 days of endogenous hormonal decline, the animals were treated for 3 days. The animals were randomly allocated to the treatment with herbal extracts, positive control, or vehicle groups (n = 6). DBT was administered orally at the doses of 0.01 g/kg BW/d or 1 g/kg BW/d BW and E2 (1 μg/kg BW/d; subcutaneous injection), which served as a positive control. Animals were sacrificed by decapitation after light anaesthesia with CO2 inhalation. The wet weights of uterus and livers were determined. Uteri and livers were frozen in liquid nitrogen for the RNA preparation.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. The figure summarizes the experimental design of the study. It schematically shows the workflow, as well as the summary of the treatment groups included. bw: body weight; DBT: Danggui Buxue Tang; DBT01 and DBT1: DBT at 0.01 and 1 g/kg bw/d.

2.4. Total RNA Preparation and Reverse Transcription

The total cytoplasmic RNA was extracted from the rat uteri by the standard TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). DNA residues were enzymatically eliminated by digestion (Deoxyribonuclease I, Ambion, Foster City, CA), and the removal was checked by PCR. Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and Oligo (dT) 12–18 were used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out by Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using the iCycler thermal cycler with iQ real-time detection system. The reactions were run three times in triplicate. After vortexing, 50 μL aliquots of the mix were pipetted in each well of the 96-well thin-wall PCR plate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). PCR reactions consisted of a first denaturing cycle at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 50 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 15 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Fluorescence was quantified at the end of the 60°C annealing step and product identity was confirmed by a melting curve analysis (60–95°C). Primer sequences and amplicon sizes are summarized in the Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/438531. The relative mRNA amounts of target genes were calculated after normalization to an endogenous reference gene (cytochrome C oxidase subunit 1, COX1). Results were expressed as relative amounts of mRNA compared to the vehicle control animals using the 2−ΔΔCT formula [14].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data in this work was performed using two-way analysis of variance followed by pairwise comparison of selected means using the Student's t-test. The criterion for significance was set to *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 as compared to the control.

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight and Organ Wet Weights

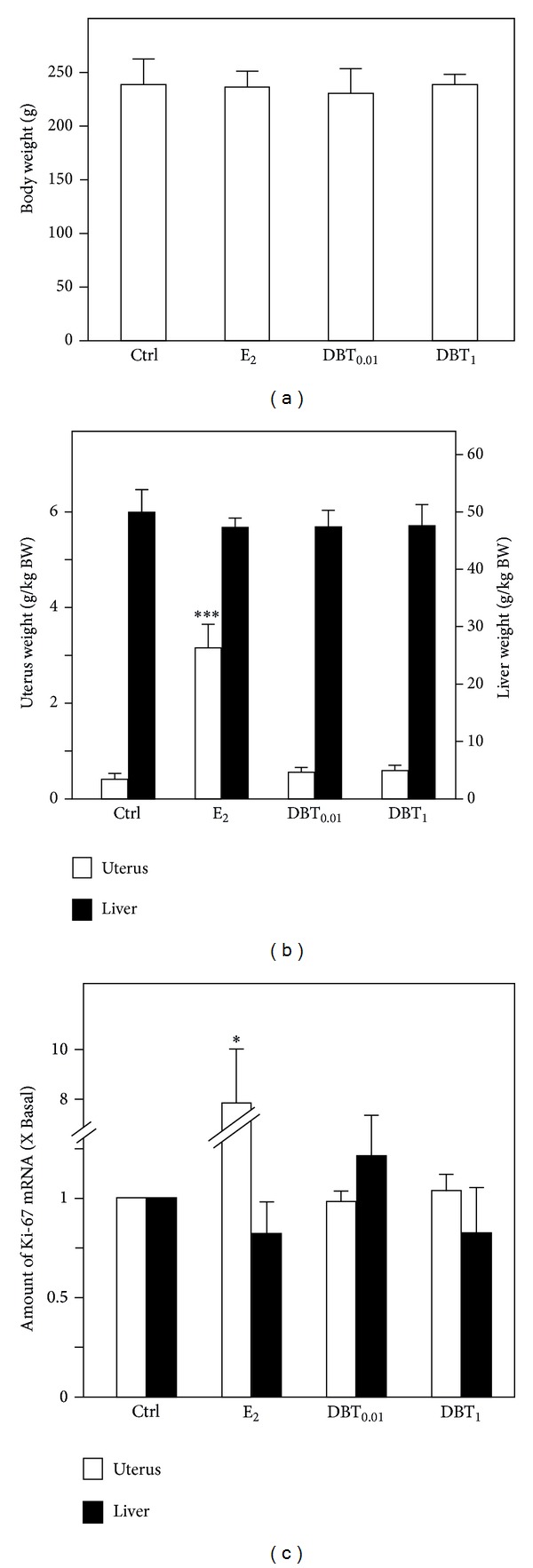

The uterotrophic response in ovariectomized rats was measured after 3 days of the drug treatment. DBT was applied at two doses of 0.01 (DBT0.01) and 1 (DBT1) g/kg BW/d. E2 was used as positive control at 1 μg/kg BW/d, and the carrier castor oil was used as a negative control. These treatments could not impact on the body weight of animals (Figure 2(a)). Regarding the wet weights, E2 treatment for 3 days caused a significant increase in uterine wet weight of more than 5-fold but did not affect the liver weight (Figure 2(b)). The treatment with DBT, for both concentrations of DBT0.01 and DBT1, had no effect on the weight of uterus and liver (Figure 2(b)). This observation was in line with the expression of the mRNA of Ki-67, a sensitive proliferation marker in uterus, which however was unchanged after the DBT treatment (Figure 2(c)). The expression of Ki-67 mRNA is highly stimulated in response to the treatment with E2 (Figure 2(c)). In liver, none of the treatments resulted in a statistically significant impact on the expression of Ki-67 (Figure 2(c)).

Figure 2.

The effect of E2 or DBT on animal body and organ weight. (a) The ovariectomized animals were treated by E2 (at 1 μg/kg BW/d; subcutaneous) or DBT (at 0.01 g/kg/d BW and 1 g/kg/d BW, orally) for three days; untreated ovariectomized animals served as a control group (Ctrl.). The body weight of rats before sacrifice was determined. The wet organs including uteri and livers were weighed. (c) The regulation of mRNA expression of the proliferation markers Ki-67 in uteri and livers was analyzed by semiquantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

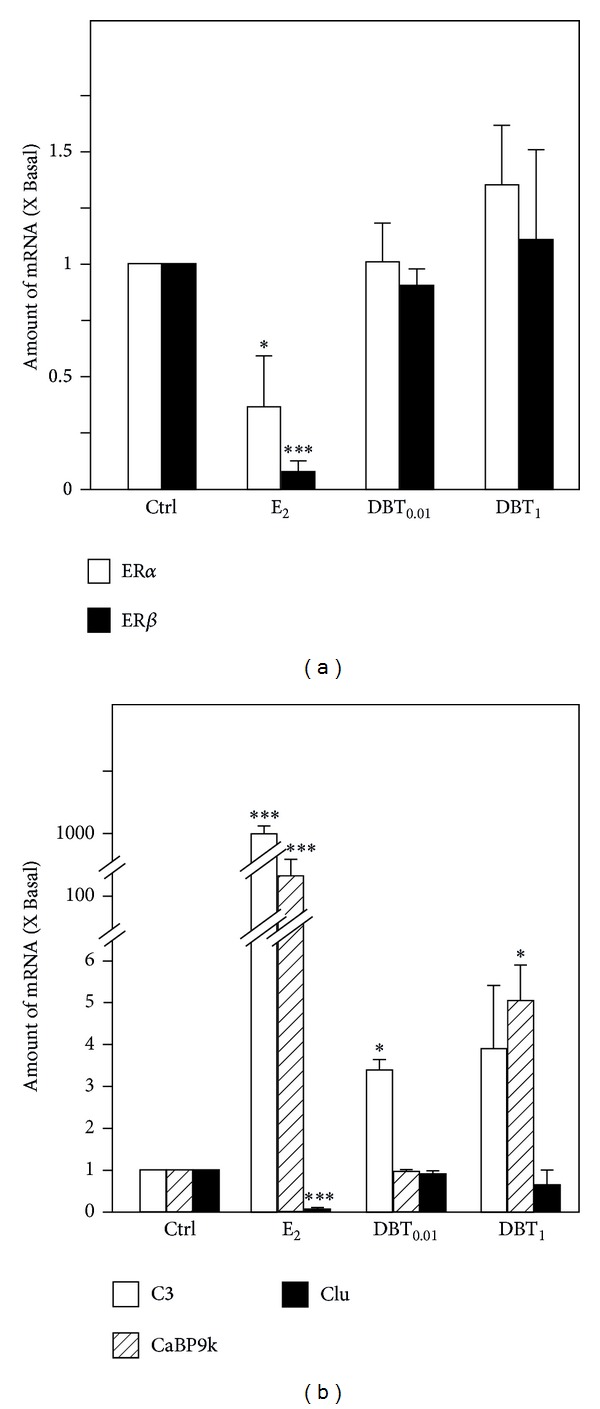

3.2. Estrogen-Associated Gene Expression in Uterus and Liver

The mRNA expression of ERα and ERβ had been detected in the rat uterus under all treatment conditions. After the treatment with E2, the ERα and ERβ mRNAs showed the expected significant downregulation, as compared to the control animals, while DBT application could not affect the mRNA expression of ERα and ERβ (Figure 3(a)). For ER action in the uterus, some very sensitive marker genes are known to monitor the estrogenic responses, that is, complement C3 (C3), calcium-binding protein 9 kDa (CaBP9k), and clusterin (Clu). In uterus, E2 treatment resulted in several hundredfold significant upregulation of the mRNA encoding C3 and CaBP9k, accompanied by a significant downregulation of Clu mRNA expression (Figure 3(b)). Apparently, DBT was capable of triggering very mild upregulation (not exceeding 5-fold) of the ER-dependent regulated genes C3 and CaBP9k. The higher dose of DBT caused a downregulation of Clu mRNA expression, which did not reach levels of statistical significance because of the high standard deviation of the mean value (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

Regulation of expression of estrogen receptors and estrogen response genes in the uteri. (a) The mRNA expression of ERα and ERβ in uteri and (b) the mRNA expression of estrogen response genes including C3, CaBP9k, and Clu were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

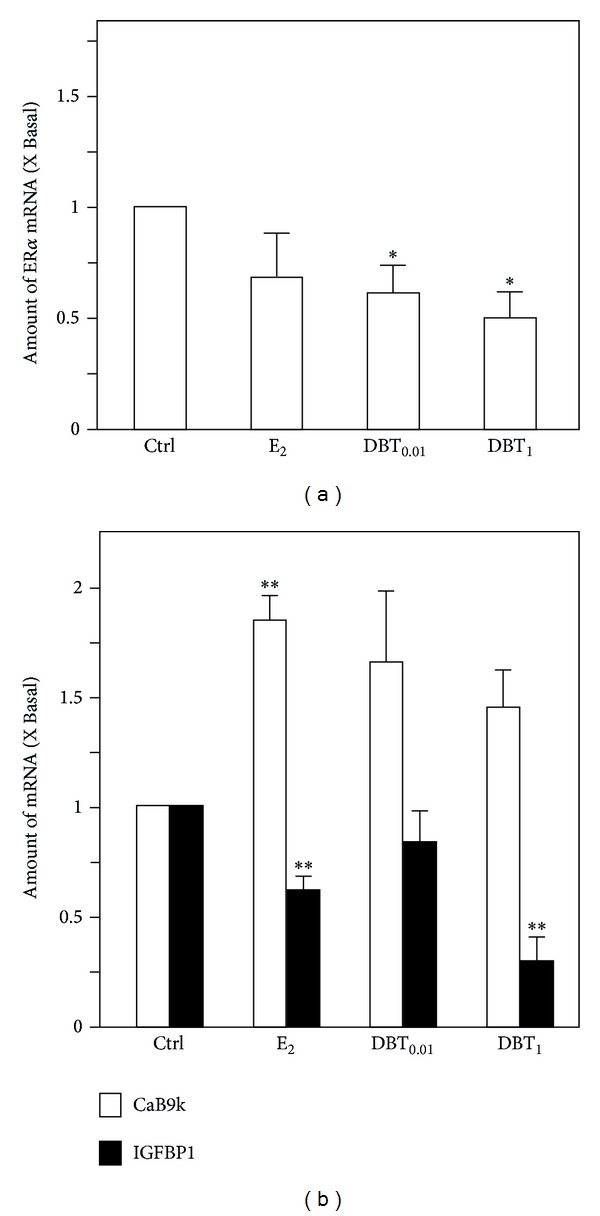

The mRNA expression of ERα had been detected in the rat liver under all treatment conditions. The autoregulatory response of downregulation of ERα by E2 did not reach the level of statistical significance, whereas both DBT concentrations downregulated steady state mRNA levels of ERα in a statistically significant manner (Figure 4(a)). To assess the expression of ERα-dependent response genes in liver, the expression levels of suitable liver-specific ER response genes, that is, CaBP9k and insulin-like growth factor binding protein I (IGFBP1), were determined. The E2 treatment resulted in an upregulation of CaBP9k mRNA expression and in the downregulation of 1GFBP1 mRNA expression in the liver (Figure 4(b)). The treatment with high dose of DBT (DBT1) significantly reduced the expression of IGFBP1. The increased expression of CaB9k was revealed after DBT treatment at both concentrations but in both cases did not reach the level of statistical significance because of the variation (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

Regulation of expression of estrogen receptors and estrogen response genes in livers. The mRNA expression of ERα in livers (a) and the mRNA expression of the estrogen response genes including CaBP9k and IGFBP1 in livers (b) were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

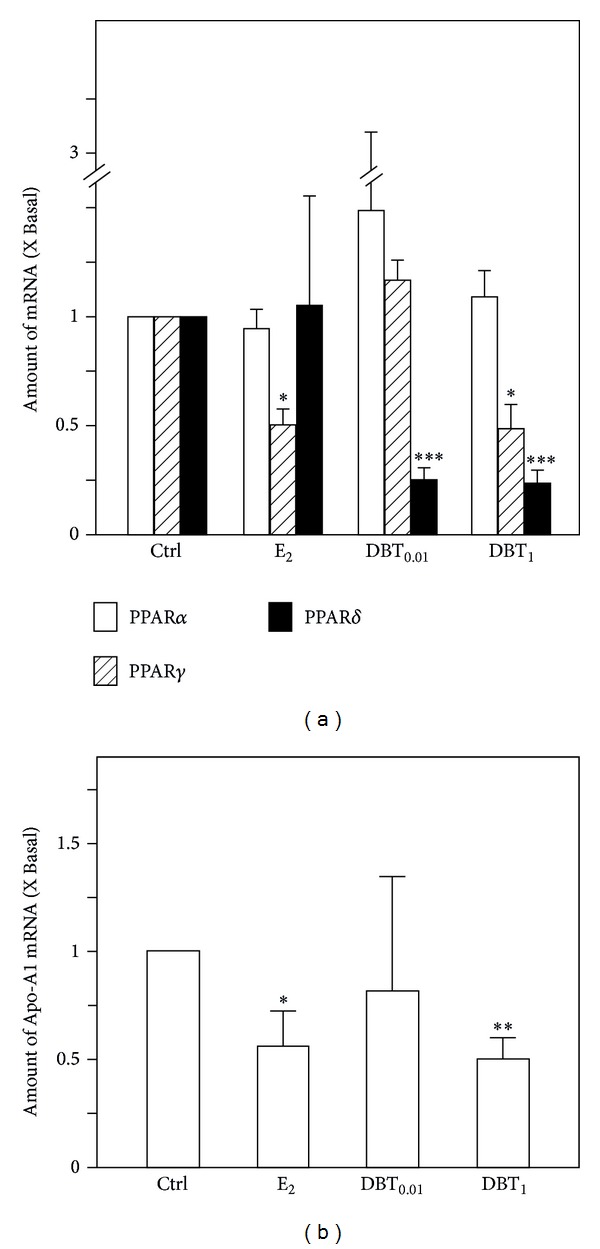

3.3. Lipid Metabolism-Associated Gene Expression in Liver

Because DBT is believed to increase “Qi” we investigated the expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism. Being the major site for lipid metabolism, liver function is linked to obesity, which in turn is a risk factor for the diseases in hormone-dependent organs, like breast cancer. We therefore investigated the expression of Apolipoprotein A-I (Apo-A1) as the major component of HDL-cholesterol and of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR), which represent lipid sensors and are in various ways involved in the regulation of energy metabolism. The upregulation of PPARα by DBT did not reach the level of statistical significance. Regarding PPARγ, DBT at a concentration of 1 g/kg BW/d downregulated the expression of its mRNA (Figure 5(a)). This downregulation was similar to that induced by E2. On the contrary, an effect which was clearly independent of potential estrogenic properties of DBT was the pronounced downregulation of PPARδ mRNA expression by both doses of DBT (Figure 5(a)). These results clearly point to the fact that DBT could regulate the expression of receptors intimately involved in the regulation of the availability and consumption of energy from fat through the modulation of expression of the receptors of the PPAR family. As a potential link to complications of the metabolic syndrome, regulation of cholesterol metabolism is of interest. We therefore assessed the regulation of expression of Apo-A1 mRNA. The expression pattern is indicative of an estrogen-like property of DBT in the concentration of 1 g/kg BW/d, which like E2 downregulated Apo-A1 mRNA expression.

Figure 5.

The gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and Apo-A1 in livers. (a) The mRNA expression of PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ in livers was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. (b) The mRNA expression of Apo-A1 in livers was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

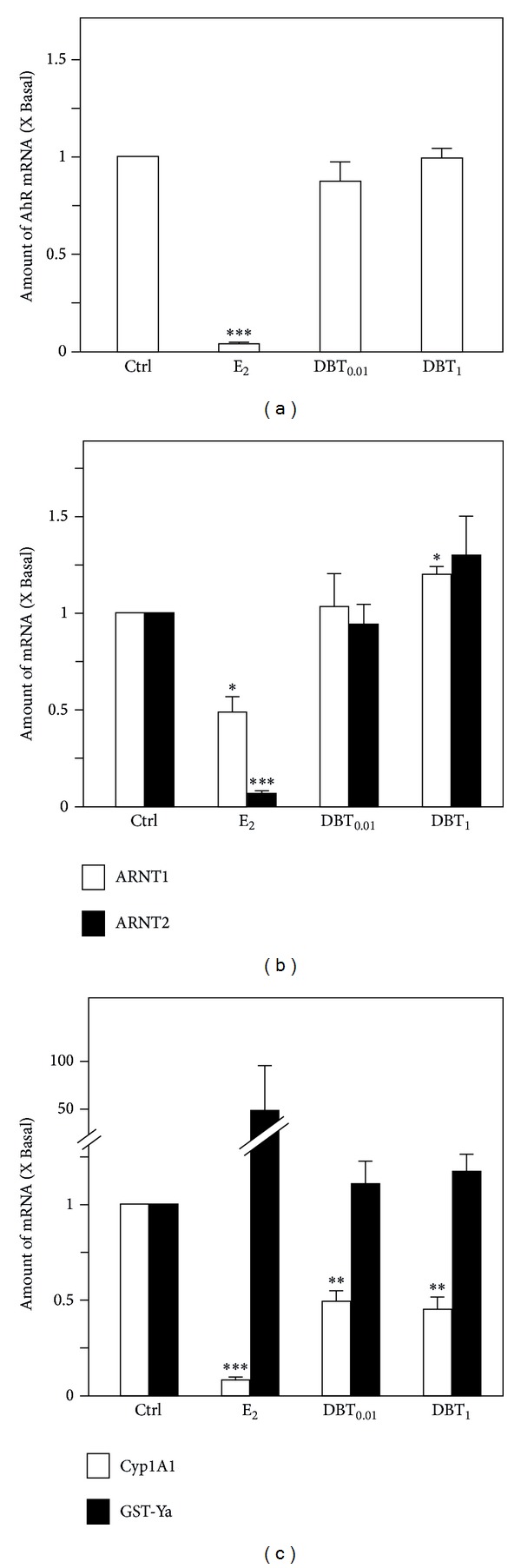

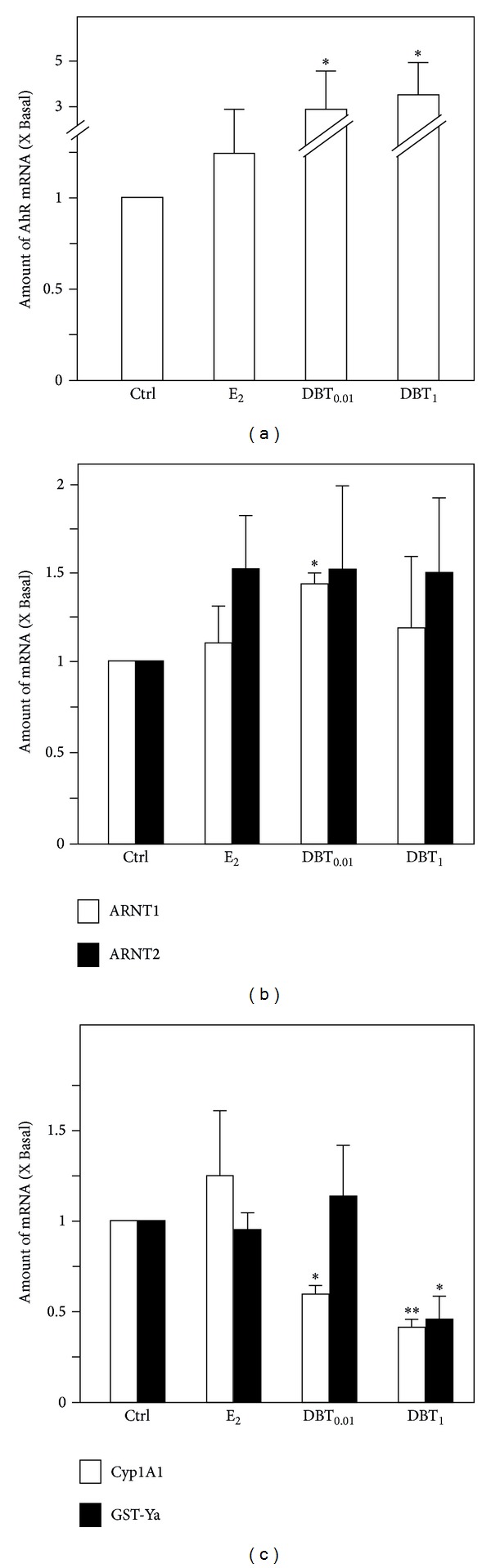

3.4. The Regulation of DBT on Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Pathway in Uterus and Liver

Efficient detoxification is also crucial for health. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is known to trigger the expression of metabolizing/detoxifying enzymes in liver and other tissues, which is acting in a coordinated fashion with the battery of Nrf2-regulated enzymes. Here, we investigated the expression of AhR, AhR family members, and AhR responsive genes in uterus and liver by DBT in comparison to E2. Overall, we detected a tissue specific regulation of expression of AhR, AhR family members, and response genes following treatment with DBT.

In uterus, AhR mRNA expression was strongly downregulated in response to E2, whereas no alteration was apparent in response to DBT (Figure 6(a)). The expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 1 (ARNT 1) mRNA, the coregulator of AHR, was downregulated by E2, whereas DBT at the high dose leads to an upregulation of ARNT1 mRNA levels in this organ. Regarding ARNT2, a strong downregulation of mRNA expression resulted in the uterus in response to E2 treatment, an effect not detectable in response to DBT (Figure 6(b)). Cytochrome P450 (family 1) A1 (Cyp1A1) and Glutathione-S-transferases Ya (GST-Ya) are regarded as very sensitive response genes for AhR function. Cyp1A1 mRNA levels in the uterus were strongly downregulated by E2, an effect also detectable in response to both doses of DBT, but at a lower degree (Figure 6(c)). GST-Ya mRNA expression was only found to be upregulated in response to E2. DBT treatment in both doses did not affect GST-Ya mRNA expression in the uterus (Figure 6(c)).

Figure 6.

Regulation of expression of AhR-related genes in uteri. (a) The mRNA expression of AhR in uteri, (b) the mRNA expression of ARNT1 and ARNT2 in uteri, and (c) the mRNA expression of Cyp1A1 and GST-Ya in uteri were analyzed by semiquantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

In liver, a mild, statistically not significant upregulation of AhR mRNA was detectable in response to E2 treatment, whereas DBT strongly induced AhR mRNA expression to over 3-fold (Figure 7(a)). The mRNA level of ARNT1 could only be induced by the low dose of DBT, but not for E2, and high dose of DBT. Furthermore, all three treatments appeared to upregulate ARNT2 mRNA expression; however, none of the values could reach the level of statistical significance (Figure 7(b)). E2 treatment resulted in a mild but not significant upregulation of Cyp1A1 mRNA levels, whereas DBT downregulates Cyp1A1 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner. On the contrary, E2 treatment did not result in an alteration of mRNA expression of GST-Ya, whereas DBT in high dose downregulated GST-Ya mRNA expression in a statistically significant, dose dependent manner (Figure 7(c)).

Figure 7.

Regulation of expression of AhR-related genes in livers. (a) The mRNA expression of AhR in livers, (b) the mRNA expression of ARNT1 and ARNT2 in livers, and (c) the mRNA expression of Cyp1A1 and GST-Ya in livers were analyzed by semiquantitative real-time PCR analysis. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from the respective controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Though DBT exhibited potential estrogenic effects in vitro [5, 6, 8], the information on potential hormonal activities of DBT in vivo is limited. It is well known that proliferation of endometrial cells is under the control of estrogens and that the risk of endometrial carcinoma increases with estrogen replacement therapy [15]. In addition, since natural compounds with estrogen-like activities often exhibit organ selective properties in vivo, we evaluated the uterotrophic experiment performed in an organ dependent manner. We assessed potential effects of DBT in the uterus, as an organ of reproductive tract representing a classical target organ of estrogen action, and in the liver as the major metabolic site being one of the organs expressing the ERα predominantly. Therefore, to study the influence of DBT in the absence of endogenous estrogen, we used ovariectomized female rats to evaluate the ER selectivity of DBT in uterus and liver.

The results showed that DBT did not alter uterine and liver wet weight or the level of expression of proliferation markers and ERs at any of the investigated doses. For ER action in the uterus, some very sensitive marker genes are known which pick up estrogenic responses, that is, the upregulation of C3 and CaBP9k and the downregulation of Clu. C3 and CaBP9k could be upregulated by E2, whereas Clu was downregulated by response to E2 treatment in the uterus. DBT did very mildly mimic estrogenic responses for C3 and CaBP9k, but not for Clu. This is interesting as upregulation of C3 and CaBP9k involves ERE-response elements [16, 17] whereas the precise mechanism of ER mediated downregulation of Clu is not known. However, reflecting the transcription factor binding sites contained in Clu promoter involvement of SP1- and AP-mediated processes is likely [18]. In parallel, the liver changes of expression of CaBP9k and IGFBP1 had been established as estrogenic response markers, although the overall response was by far lower than the one detectable for CaBP9k or C3 in the uterus. In the liver, DBT again exerted weak estrogenic properties in the 3-day uterotrophic assay. Effects were only detectable using the most sensitive gene expression markers of estrogen action.

Liver in addition is a major site for lipid metabolism which is linked to obesity and which in turn is a risk factor for the diseases in hormone dependent organs like breast cancer. We therefore investigated the expression of Apo-A1 as the major component of HDL-cholesterol [19] and of PPAR receptors which are in various ways involved in the regulation of energy metabolism. They are also known targets for natural compounds and binding to them improves, for example, glucose uptake [20]. Our results clearly point to the fact that DBT through modulation of expression of the receptors of the PPAR family may contribute to the regulation of the availability and utilization of energy from fat. Numerous reviews summarize the regulation of metabolic pathways following activation of PPARs [21, 22], a topic which is out of focus of this paper. However, two features of our results regarding PPAR deserve discussion. A strong downregulation of PPARδ in response to DBT was observed. In this connection it is important to mention that PPARδ responded to DBT treatment apparently in an estrogen/ER independent manner. The functional consequences of downregulation of PPARδ expression by DBT need to remain open at this point; however, it is not due to an autoregulatory downregulation of PPARδ following binding of constituents of DBT, because DBT neither stimulated PPARδ nor PPARγ-dependent reporter gene activation in a transient transfection assay (data not shown). However, activation of a PPARδ dependent signaling cascade by DBT would be interesting, as PPARδ is the major regulator for mobilization of fat and energy expenditure from fat [22] and because of this phenotype potentially linked to obesity and its prevention.

In contrast, PPARγ at least at a high dose of DBT responded in an estrogen-like manner by being downregulated. One important feature in addition to its insulin-sensitizing properties of PPARγ is that it determines stem cell fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Skeletal effects of PPARγ are well established in the meantime. It activates adipogenic differentiation, thereby inhibiting osteogenic differentiation [23, 24]. This situation would be disadvantageous for menopausal women and this is why downregulation of PPARγ by DBT may point to a beneficial effect.

It is long known that the AhR pathway triggers the expression of metabolizing enzymes in the liver and in other tissues mostly in a coordinated fashion with the battery of Nrf2 regulated enzymes [25], thereby contributing to the detoxification process. We recently showed that there exists a link between estrogen function and regulation of AhR and members AhR signaling cascade in the uterus [26, 27]. Therefore, we comparatively investigated the regulation of expression of AhR, AhR family members, and AhR response genes in uterus and liver by DBT in comparison to estradiol. First, we confirmed the estrogenic response pattern of the AhR gene battery members [26]. For DBT treatment we overall detected a tissue specific regulation of expression of AhR, AhR family members, and response genes following treatment with DBT. Cyp1A1 and GST-Ya, in addition to being members of first (Cyp1A1) and second pass (GST-Ya) metabolic enzymes, are regarded as very sensitive response genes regarding crosstalk mechanisms of involving AhR and ER pathways [26] and here were tested too. As an interesting observation DBT treatment exhibited an estrogen-like response pattern for regulation of Cyp1A1 expression, but not for GST-Ya, indicative of the fact that DBT function in the liver is associated with both estrogen-like and estrogen-independent properties. The same holds presumably for AhR triggered responses. For the future it will be interesting to see whether DBT and/or its constituents will trigger AhR-mediated reporter gene activities.

In addition, although weakly, we found ARNT molecules to be upregulated by DBT in the liver. This is interesting as some of the authors involved in this paper recently described the upregulation of HIF1α by DBT ultimately leading to upregulation of erythropoietin [8]. ARNT1 is also called HIF1β and represents the heterodimeric dimerization partner of HIF1α in mediation of its nuclear responses [28]. In other words, we show here that DBT upregulates not only HIF1α but also HIF1β/ARNT1 thereby potentially supporting the effect of HIF1α on erythropoiesis.

In summary, we showed for the first time that DBT regulates the mRNA levels of members of the AhR signaling cascade, thereby exhibiting both estrogen-like and estrogen receptor independent activities, presumably leading to a distinct pattern of detoxification mechanisms. The final major result was that effects of DBT appear to be organ selective, influencing functions relevant to menopausal health. On the safety side there was no indication for estrogen dependent stimulation of proliferation within organs of the reproductive tract. Regarding efficacy DBT exhibits weak estrogenic properties and regulates the expression of functionally interconnected lipid sensors comprising amongst others the PPAR and AhR families of molecules [29, 30], the latter establishing a link to detoxification and energy metabolism. We hypothesize that DBT therefore may have properties which directly and indirectly impact on menopausal health.

Supplementary Material

Gene expression analysis was performed in RNA preparations from tissue samples of uterus and liver. Information on analyzed genes, primer sequences used as well as amplicon sizes is given in Supplementary Table 1.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants from Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (HKUST 6419/06 M and N_HKUST629/07, 662608), Croucher Foundation (CAS-CF07/08.SC03) to Karl W. K. Tsim, and German Research Foundation (DFG Vo410/6-5) and German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD 50023165) to Günter Vollmer. Contributors of TU-Dresden acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the TU-Dresden.

Abbreviations

- TCM:

Traditional Chinese medicine

- DBT:

Danggui Buxue Tang

- ASR:

Angelicae Sinensis Radix

- AR:

Astragali Radix

- AhR:

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- Apo-A1:

Apolipoprotein A-1

- E2:

17β-Estradiol

- ER:

Estrogen receptor

- ERE:

Estrogen response element

- HRT:

Hormone replacement therapy

- PPAR:

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Harlow BL, Signorello LB. Factors associated with early menopause. Maturitas. 2000;35(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brzezinski A, Debi A. Phytoestrogens: the “natural” selective estrogen receptor modulators? European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1999;85:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glazier MG, Bowman MA. A review of the evidence for the use of phytoestrogens as a replacement for traditional estrogen replacement therapy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(9):1161–1172. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong TTX, Zhao KJ, Gao QT, et al. Chemical and biological assessment of a Chinese herbal decoction containing Radix Astragali and Radix Angelicae Sinensis: determination of drug ratio in having optimized properties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(7):2767–2774. doi: 10.1021/jf053163l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao QT, Choi RCY, Cheung AWH, et al. Danggui buxue tang—a Chinese herbal decoction activates the phosphorylations of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and estrogen receptor α in cultured MCF-7 cells. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(2):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CC, Cheng KF, Lo WM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multiple-dose escalation study of a Chinese herbal medicine preparation (Dang Gui Buxue Tang) for moderate to severe menopausal symptoms and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2013;20(2):223–231. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318267f64e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng KYZ, Choi RCY, Xie HQH, et al. The expression of erythropoietin triggered by Danggui Buxue Tang, a Chinese herbal decoction prepared from Radix Astragali and Radix Angelicae Sinensis, is mediated by the hypoxia-inducible factor in cultured HEK293T cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;132(1):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi RCY, Gao QT, Cheung AWH, et al. A Chinese herbal decoction, danggui buxue tang, stimulates proliferation, differentiation and gene expression of cultured osteosarcoma cells: genomic approach to reveal specific gene activation. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:13 pages. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen085.307548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma XQ, Shi Q, Duan JA, Dong TTX, Tsim KWK. Chemical analysis of Radix Astragali (Huangqi) in China: a comparison with its adulterants and seasonal variations. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(17):4861–4866. doi: 10.1021/jf0202279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao KJ, Dong TTX, Tu PF, Song ZH, Lo CK, Tsim KWK. Molecular genetic and chemical assessment of radix Angelica (Danggui) in China. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(9):2576–2583. doi: 10.1021/jf026178h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song ZH, Ji ZN, Lo CK, et al. Chemical and biological assessment of a traditional Chinese herbal decoction prepared from radix astragali and radix angelicae sinensis: orthogonal array design to optimize the extraction of chemical constituents. Planta Medica. 2004;70(12):1222–1227. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-835855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanno J, Onyon L, Peddada S, Ashby J, Jacob E, Owens JW. The OECD program to validate the rat uterotrophic bioassay. Phase 2: dose-response studies. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111(12):1530–1549. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winer J, Jung CKS, Shackel I, Williams PM. Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Analytical Biochemistry. 1999;270(1):41–49. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K. Hormone replacement therapy and cancers: the biological roles of estrogen and progestin in tumorigenesis are different between the endometrium and breast. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;212(1):1–12. doi: 10.1620/tjem.212.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris JD, Fan D, Wagner BL, McDonnell DP. Identification of the sequences within the human complement 3 promoter required for estrogen responsiveness provides insight into the mechanism of tamoxifen mixed agonist activity. Molecular Endocrinology. 1996;10(12):1605–1616. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee G-S, Choi K-C, Han H-J, Jeung E-B. The classical and a non-classical pathways associated with NF-κB are involved in estrogen-medicated regulation of Calbindin-D9k gene in rat pituitary cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007;277(1-2):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong P, Taillefer D, Lakins J, Pineault J, Chader G, Tenniswood M. Molecular characterization of human TRPM-2/clusterin, a gene associated with sperm maturation, apoptosis and neurodegeneration. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1994;221(3):917–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geis R, Diel P, Degen GH, Vollmer G. Effects of genistein on the expression of hepatic genes in two rat strains (Sprague-Dawley and Wistar) Toxicology Letters. 2005;157(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kühn C, Arapogianni NE, Halabalaki M, et al. Constituents from cistus salvifolius (Cistaceae) activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ but not -δ And stimulate glucose uptake by adipocytes. Planta Medica. 2011;77(4):346–353. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Be fit or be sick: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are down the road. Molecular Endocrinology. 2004;18(6):1321–1332. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yessoufou A, Wahli W. Multifaceted roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) at the cellular and whole organism levels. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2010;40 doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13071.w13071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grün F, Blumberg B. Perturbed nuclear receptor signaling by environmental obesogens as emerging factors in the obesity crisis. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 2007;8(2):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai M, Sousa KM, MacDougald OA, Rosen CJ. The many facets of PPARγ: vovel insights for the skeleton. The American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;299(1):E3–E9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00157.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köhle C, Bock KW. Coordinate regulation of Phase I and II xenobiotic metabolisms by the Ah receptor and Nrf2. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2007;73(12):1853–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kretzschmar G, Papke A, Zierau O, et al. Estradiol regulates aryl hydrocarbon receptor expression in the rat uterus. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2010;321(2):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rataj F, Möller FJ, Jähne M, et al. Regulation of uterine AHR battery gene expression by 17β-Estradiol is predominantly mediated by estrogen receptor α. Archives of Toxicology. 2012;86(10):1603–1612. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0870-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaelin WG. Proline hydroxylation and gene expression. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005;74:115–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beaven SW, Tontonoz P. Nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism: targeting the heart of dyslipidemia. Annual Review of Medicine. 2006;57:313–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods CG, Heuvel JPV, Rusyn I. Genomic profiling in nuclear receptor-mediated toxicity. Toxicologic Pathology. 2007;35(4):474–494. doi: 10.1080/01926230701311351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gene expression analysis was performed in RNA preparations from tissue samples of uterus and liver. Information on analyzed genes, primer sequences used as well as amplicon sizes is given in Supplementary Table 1.