Abstract

Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin (TcsL) is distinct among large clostridial toxins (LCTs), as it is markedly reduced in its rate of intoxication at pH 8.0 yet is cytotoxic at pH 4.0. Results from the present study suggest that TcsL's slow rate of intoxication at pH 8.0 is linked to formation of a high-molecular-weight complex containing dissociable pH 4.0-sensitive polypeptides. The cytosolic delivery of TcsL's enzymatic domain by using a surrogate cell entry system resulted in cytopathic effect rates similar to those of other LCTs at pH 8.0, further indicating that rate-limiting steps occurred at the point of cell entry. Since these rate-limiting steps could be overcome at pH 4.0, TcsL was examined across a range of pH values and was found to dissociate into distinct 45- to 55-kDa polypeptides between pH 4.0 and pH 5.0. The polypeptides reassociated when shifted back to pH 8.0. At pH 8.0, this complex was resistant to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and multiple proteases; however, following dissociation, the polypeptides became protease sensitive. Dissociation of TcsL, and cytotoxicity, could be blocked by preincubation with ethylene glycol bis(sulfosuccinimidylsuccinate), resulting in cross-linking of the polypeptides. TcsL was also examined at pH 8.0 by using SDS-agarose gel electrophoresis and transmission electron microscopy and was found to exist in a higher-molecular-weight complex which resolved at a size exceeding 750 kDa and also dissociated at pH 4.0. However, this complex did not reassemble following a shift back to pH 8.0. Collectively, these data suggest that TcsL is maintained in a protease-resistant, high-molecular-weight complex, which dissociates at pH 4.0, leading to cytotoxicity.

Clostridium sordellii is a gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic pathogen which causes a variety of diseases including postpartum toxic shock syndrome, septic arthritis, neonatal omphalitis, and sudden death syndrome (1, 10, 14, 23, 24, 26, 27 and C. J. Lewis and R. Naylor, Letter, Vet. Rec. 138:262, 1996). This list of diseases has recently been expanded with the implication of C. sordellii in the deaths of intravenous drug users following injection of contaminated heroin (18). In addition, C. sordellii has been identified as a possible cause of death in recent cases of patients receiving musculoskeletal allografts (13). Indeed, C. sordellii appears to have the capacity to cause a diverse number of diseases. For example, 16 different types of disease have been reported in approximately 30 published studies of C. sordellii infections. Unfortunately, very little is known about the C. sordellii mechanism of pathogenesis, making it difficult to provide tenable explanations for this organism's multifaceted role in disease.

To date, only three putative virulence factors from C. sordellii have been studied. C. sordellii produces a lecithinase (phospholipase C), which is similar to alpha-toxin, a major virulence factor from Clostridium perfringens (12). Two C. sordellii virulence factors, lethal toxin (TcsL) and hemorrhagic toxin (TcsH), have also been studied in some detail. Toxoids of TcsL and TcsH are effective vaccines against C. sordellii spore challenge in a guinea pig model (4), indicating that these toxins may play a pivotal role in disease progression.

TcsL and TcsH are members of the family of large clostridial toxins (LCTs), which is composed of at least five toxins possessing glycosyltransferase activity (5). Members of the LCT family of toxins, in addition to TcsL and TcsH, include Clostridium difficile toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB) and Clostridium novyi alpha-toxin (Tcnα). Each LCT induces pronounced cytopathic effects (CPE) in cultured mammalian cells, and these effects are apparently a prelude to cell death. For the induction of CPE, LCTs glycosylate, and thereby inactivate, members of the Ras family of small GTPases. TcdA, TcdB, TcsH, and Tcnα preferentially inactivate Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 (3) by the transfer of sugar moieties derived from UDP-glucose or N-acetylglucosamine to reactive threonines in the effector-binding loop of target GTPases. TcsL also glycosylates small GTPases but differs from other LCTs by targeting Ras, Rac, Rap, and Ral (3).

The enzymatic domain of LCTs has been narrowed to the amino-terminal 546 residues. The difference in substrate specificity between TcsL and TcdB is due to sequence variation in the region of residues 364 to 516 within the enzymatic fragment (11). Residues important for binding UDP-glucose are found at D286 and D288, while glucosyltransferase activity requires D270 and R273 (7). Further studies have also implicated W102 in interaction with UDP-glucose by TcdB and TcsL (6). Despite these similarities, TcsL induces delayed CPE relative to induction by TcdB (8, 22), and it has been suggested that the slower cytotoxicity could be due to delays in TcsL cell entry (8). In addition, we recently reported on the enhanced cytotoxicity of TcsL following exposure to pH 4.0 conditions (22). This finding indicated that TcsL might be substantially more active at pH 4.0, and this could be due to enhanced interactions with the cell following acid-induced conformational changes.

To better understand the connection between cell entry and the activation of TcsL at pH 4.0, we analyzed the cytotoxic effects of TcsL's enzymatic domain by using a surrogate cell entry system and found that alternative mechanisms of cell entry markedly increased the rate of intoxication. In addition, direct analysis of TcsL at pH 4.0 revealed the dissociation of a high-molecular-weight complex containing polypeptides of the toxin. Findings from the present study indicate that intoxication by TcsL is limited by the need for the dissociation of a multimeric complex, which occurs optimally under acid pH conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and toxin purification.

Human epitheloid carcinoma (HeLa) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). Cells were grown at 37°C in the presence of 6% CO2 and were used between passages 10 and 20. C. sordellii ATCC 9714, C. difficile ATCC 10463, and C. novyi ATCC 19402 strains were used in this study for the purification of TcsL, TcdB, and Tcnα, respectively. TcsL, TcdB, Tcnα, protective antigen (PA), and a truncated form of lethal factor (LFn) TcdB, residues 1 to 556 (LFnTcsL1-556), were isolated as previously described (22, 25).

Construction, expression, and isolation of LFnTcsL1-556.

The region encoding the enzymatic domain of TcsL was amplified from C. sordellii ATCC 9714 genomic DNA by PCR using the forward primer 5′-GCGCGCGGATCCATGAACTTAGTTAACAAAGCCCAA-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GCGCGCGGATCCTTATTATAATATTTTTTTAGAAACATAATC-3′ to generate the tcsL gene encoding residues 1 to 1688 of (tcsL1-1668) with a 5′ and 3′ BamHI site. The gene tcsL1-1668 was then restricted with BamHI, and lfn was genetically fused to tcsL1-1668 by ligation overnight at 16°C with BamHI-restricted plasmid pABII, a derivative of pET15b containing lfn. This construct generated an in-frame fusion of lfn and tcsL1-1668, and the resulting plasmid was labeled pMQ101. The correct genetic fusion resulted in joining the 3′ end of lfn at the codon TCC encoding S254, followed by sequences within the multiple cloning site that encoded the linker region and a string of residues (PGGGGGS), with the 5′ end of tcsL1-1668 at the ATG codon encoding M1. Plasmid pMQ101 was then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α (Clontech), and candidate clones were screened by mini-prep analysis. In-frame, correctly oriented clones were identified by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing and were subsequently transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Stratagene). For protein expression, cells were grown at 37°C until an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 was reached, at which point expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiolgalactopyranoside (Denville Scientific, Inc.) at 16°C for 16 h. LFnTcsL1-556 was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). The purified protein migrated within the predicted size range (∼94 kDa) as analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and was reactive to both anti-LF and TcdB polyclonal antisera.

Glucosylation, cell viability, and quantification of CPE.

Differential glucosylation assays were performed in a similar manner to those previously described (22), except PA (300 pmol) plus LFnTcsL1-556 (300 pmol) was substituted for acid-pulsed TcsL. Ras glucosylation assays were also performed as previously described (22), with the substitution of Ras (Calbiochem) in place of cell extracts. Cell viability assays were performed by using a WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt] (Dojindo Laboratories) colorimetric assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following formula was used to determine percent cell viability: [(Atest − Abackground)/(Acontrol − Abackground) × 100], where A is the absorbance at an optical density at 450 nm, background is media alone, and control refers to cells treated with media alone. Percent CPE was calculated by counting a minimum of 100 cells in three fields for each sample. Fully rounded cells were scored positive for CPE, and the final percent CPE was calculated as follows: % rounded cellstest − % rounded cellscontrol, where control refers to cells treated with media alone. In a standard assay, cells were treated with 100 fmol of TcdB or TcsL in a volume of 100 μl. For assays with the fusion proteins, cells were treated with 30 pmol of PA and 1 pmol of either LFnTcsL1-556 or LFnTcdB1-556 in a volume of 100 μl.

Electrophoretic analysis of TcsL, TcdB, and Tcnα, and immunoblot analysis of TcsL.

Ammonium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 3.8) was added to 10 μg of TcsL, TcdB, or Tcnα in various amounts to obtain the indicated pH in each sample. Samples were incubated with this buffer for 30 min at room temperature, at which point the indicated samples were raised back to pH 8.0 by using 250 mM Tris, pH 9.0, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were then separated by using either SDS-10% PAGE or SDS-1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis (SDS-AGE) as indicated and observed by using Coomassie blue staining. Indicated TcsL samples were subjected to Western blot analysis using a C. difficile TcdB-specific primary antibody (TechLab, Inc.).

Electroelution.

Following separation via SDS-10% PAGE or SDS-1.5% AGE, the band representing TcsL or the high-molecular-weight complex was excised from the gel and subjected to electroelution in the presence of SDS by using a Centrilutor Micro-Electroeluter (Millipore). Proteins were allowed to electroelute for 2 h at room temperature. Following elution and concentration, the protein samples were again analyzed via SDS-10% PAGE to determine the content of protein complexes. Initial gels contained 15 μg of protein per lane and were visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis of TcsL.

TcsL samples at pH 8.0 were observed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a negative staining procedure. Briefly, TcsL (300 ng/μl) was placed on a copper support surface and allowed to adhere for 2 min. Following adherence, 100 μl of phosphotungstic acid (PTA) was applied to the grid for a 1-min incubation. Subsequently, the PTA was removed and the support was allowed to dry. Following drying, the protein was observed via TEM at a magnification of ×105. Additional samples were incubated at pH 4.0 for 30 min and subsequently observed by using TEM.

TcsL cross-linking with sulfo-EGS.

TcsL at pH 8.0 was cross-linked by using ethylene glycol bis(sulfosuccinimidylsuccinate) (sulfo-EGS; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.), a homobifunctional cross-linking reagent, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, TcsL (200 μg) was buffer-exchanged into 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, and subsequently incubated with sulfo-EGS in a volume of 100 μl at room temperature for 30 min. Cross-linking reactions were stopped by the addition of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, for 15 min at room temperature. A decreasing range of sulfo-EGS concentrations from 2.5 mM to 250 pM was used to account for the effects of excess sulfo-EGS. Following cross-linking, samples were analyzed via SDS-10% PAGE and observed by using Coomassie blue staining following incubation at the indicated pH. Each sample cross-linked with a different concentration of sulfo-EGS was tested in a routine HeLa cell cytotoxicity assay. Briefly, HeLa cells at 75% confluence were incubated with TcsL-sulfo-EGS (2 μg/ml) and observed for 72 h. Cell viability was determined via the WST-8 assay as described above. As a control, TcdB was subjected to the same cross-linking conditions and sulfo-EGS concentrations described above. HeLa cells were also incubated with TcdB-sulfo-EGS to determine the effects of sulfo-EGS on TcdB-induced cytotoxicity.

Protease treatments and heat treatment of TcsL.

TcsL (10 μg) was incubated with 15 μg of the following proteases in a final volume of 25 μl: proteinase K (Geno Technology, Inc.), α-chymotrypsin (Sigma-Aldrich), V8 protease (Sigma-Aldrich), and trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich). The indicated samples were placed under pH 4.0 conditions, as described above, prior to protease treatment. All incubations were performed at room temperature and 37°C for 16 h except for the incubation of proteinase K, which was incubated at 55°C for 16 h. Additionally, protease-treated TcsL samples (2 μg/ml) were incubated with HeLa cells up to 72 h and observed visually for CPE. The indicated TcsL samples were heated at 100°C for 15 min prior to electrophoretic analysis.

RESULTS

Normalized cell entry confers similar rates of CPE for TcdB and TcsL.

Under normal cell culture conditions, TcsL induces CPE at a rate substantially slower than TcdB (16). In earlier work, it was reported that providing an extracellular pH 4.0 pulse quickened TcsL's otherwise slow time course of intoxication (22). TcsL activated by pH 4.0 conditions induced CPE at a rate similar to that of TcdB, changing the time point of 50% CPE from approximately 7 h to 90 min. At pH 8.0, cells could be protected from TcsL by the extracellular addition of antiserum up to 2 h following treatment with the toxin. These data further indicated that TcsL intoxication is limited at the stage of cell entry, but this is overcome by an extracellular acid pH. Thus, in an effort to show directly that TcsL's slow rate of cytotoxicity was due to events at the point of cell entry, we designed constructs of the enzymatic domains of TcsL and TcdB, which allowed these fragments to enter cells in an identical manner.

To normalize cell entry for the enzymatic domains (residues 1 to 556) of TcdB (TcdB1-556) and TcsL (TcsL1-556), we utilized a nontoxic derivative of anthrax lethal toxin, which consists of PA plus LF. A previous study involving the cytosolic delivery of TcdB1-556 used a derivative of anthrax lethal toxin consisting of PA and LFn, which is inactive but can interact with PA and be translocated to the cytosol (25). Genetic fusions were constructed and used as a source of LFnTcdB1-556 in the earlier work, and a similar approach was used for constructing LFnTcsL1-556 in the present study. Similar to the results of a previous study of acid pH-pulsed entry of TcsL (22), the glucosylation profiles from extracts of cells treated with LFnTcsL1-556 plus PA showed that all TcsL substrates were modified by the fusion (data not shown). Thus, the fusion appeared suitable for making comparisons between the enzymatic domains of TcsL and TcdB.

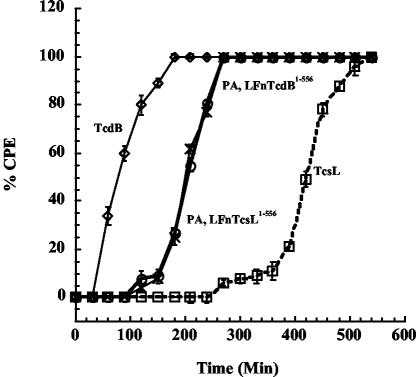

As shown in Fig. 1, LFnTcdB1-556 and LFnTcsL1-556 delivered to the cytosol with PA demonstrated similar time courses of CPE in HeLa cells. Wild-type TcdB induced 100% CPE by 3 h compared to 9 h required by TcsL for full induction of CPE. Both LFnTcdB1-556 and LFnTcsL1-556 induced 100% CPE by 4.5 h. These data further suggest that TcsL's major barrier to intoxication occurred at steps in cell entry.

FIG. 1.

Time course of CPE in TcsL- and LFnTcsL1-556-treated cells. HeLa cells were grown to confluence in a 96-well plate to ∼5 × 104 cells/well. Cells were treated with either TcdB (100 fmol), TcsL (100 fmol), LFnTcsL1-556 (1 pmol), or LFnTcdB1-556 (1 pmol) in a volume of 100 μl. PA (30 pmol) was included with the fusion proteins. Control cells were treated with media, 20 mM Tris, heat-inactivated toxin, or PA plus LFn alone. Following treatment, CPE were observed for 10 h and calculated by visualizing the number of rounded cells from a field of at least 100 cells. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean. ◊, TcdB; □, TcsL; ○, LFnTcdB1-556; ×, LFnTcsL1-556.

TcsL forms an acid pH-dissociable complex.

Under the described conditions, TcsL from C. sordellii ATCC 9714 purified as a protein doublet even after three rounds of anion-exchange chromatography. This observation is in agreement with Martinez and Wilkins, who reported a doublet in their preparation of TcsL from C. sordellii VPI 9048 (16). In addition to the doublet, we also observed the presence of ca. five smaller proteins copurifying with TcsL. These smaller proteins, ranging in size from 45 to 55 kDa, cross-reacted with antiserum that recognizes TcsL and became more prominent following long-term storage of the toxin (data not shown), suggesting these were products of TcsL.

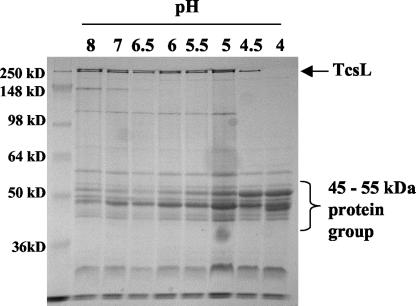

Given the observations of TcsL dissociation, we investigated whether this dissociation event might be related to TcsL's unique requirement of acid pH for activation. As shown in Fig. 2, following incubation of TcsL at pH 4.0, the toxin dissociates into a group of 45- to 55-kDa proteins. The inclusion of protease inhibitors, reducing agents, and buffers across a range of ionic strengths did not alter the dissociation profile (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Acid pH-induced dissociation of TcsL. Samples of purified TcsL (10 μg) were incubated for 30 min with various amounts of 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 3.8, to attain the indicated pH. Proteins were separated via SDS-10% PAGE and observed by using Coomassie blue staining.

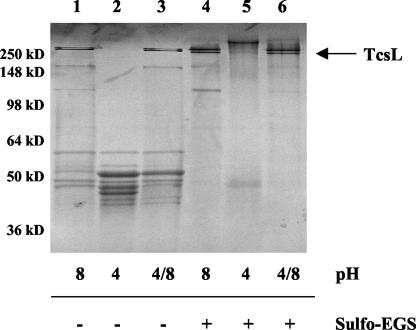

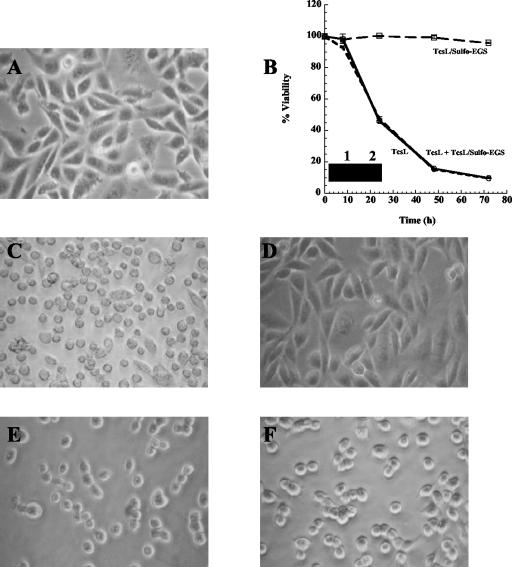

Interestingly, TcsL was able to reassemble when the sample was raised back to pH 8.0, indicating that dissociation was reversible (Fig. 3). To confirm the close association required for a complex of this kind, we cross-linked TcsL at pH 8.0 with sulfo-EGS, a homobifunctional cross-linking reagent that cross-links proteins with lysine residues within a 16-Å proximity. As shown in Fig. 3, when TcsL-sulfo-EGS was placed under pH 4.0 conditions, no dissociation was observed, indicating the close proximity of the complex components to each other. As shown in Fig. 4, TcsL-sulfo-EGS was no longer cytotoxic when incubated with HeLa cells up to 72 h and was no longer able to glucosylate Ras in vitro, while TcdB cross-linked under the same conditions retained full cytotoxicity. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4B, TcsL-sulfo-EGS did not compete with TcsL for binding in a HeLa cell cytotoxicity assay. These results further suggest that dissociation of this complex is required for interaction at the cell surface and complete cytotoxic activity.

FIG. 3.

Impact of pH shifts and cross-linking on TcsL stability. TcsL samples (10 μg) were analyzed via SDS-10% PAGE and observed by using Coomassie blue staining following incubation under various pH conditions. In lanes 3 and 6, pH 4.0 was shifted back to pH 8.0 (4/8). +, TcsL with sulfo-EGS; − TcsL without sulfo-EGS.

FIG. 4.

Toxicity, cell binding, and enzymatic activity of cross-linked TcsL. HeLa cells were incubated with TcsL, TcsL-sulfo-EGS, or TcsL plus TcsL-sulfo-EGS (2 μg/ml) for up to 72 h and observed for morphological changes associated with TcsL-induced cytotoxicity. As a comparison, HeLa cells were also incubated with TcdB or TcdB-sulfo-EGS (2 μg/ml) and observed for morphological changes. TcsL or TcsL-sulfo-EGS was also incubated in a Ras glucosylation assay as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Control untreated cells. (B) Percent viability of HeLa cells treated with TcsL, TcsL-sulfo-EGS, and TcsL plus TcsL-sulfo-EGS. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and error bars indicate the standard deviation from the mean. Inset compares glucosyltransferase activity of TcsL (lane 1) and TcsL-sulfo-EGS (lane 2). (C) TcsL-treated cells. (D) TcsL-sulfo-EGS-treated cells. (E) TcdB-treated cells. (F) TcdB-sulfo-EGS-treated cells.

Protease resistance at pH 8.0.

To determine if TcsL dissociation was specific for pH 4.0 conditions, the protein was submitted to a series of protease digestions and high-temperature incubation. As shown in Fig. 5, proteases including trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, V8 protease, and proteinase K, added in excess, were unable to induce TcsL dissociation similar to that observed at pH 4.0. However, the smaller polypeptides were sensitive to the various proteases, as these fell below the level of detection following protease treatment. As reported by Popoff (20), we confirmed that only α-chymotrypsin had any effect on TcsL activity, with CPE occurring ∼50% slower than in untreated TcsL (data not shown). TcsL was also subjected to incubation at 100°C to determine if dissociation occurs under elevated temperatures. Boiling TcsL for 15 min resulted in complete degradation of the protein, distinct from the dissociation observed in pH 4.0 samples (data not shown).

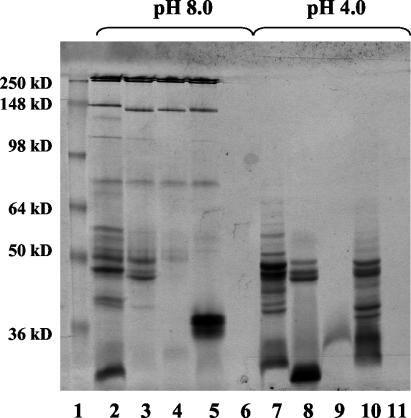

FIG. 5.

Protease treatment of TcsL. TcsL (10 μg) was incubated with an excess of each indicated protease (15 μg) overnight prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. The pH value is indicated above the gel and each pH section follows this order of protease treatment: Lanes 2 and 7, TcsL; lanes 3 and 8, TcsL plus trypsin; lanes 4 and 9, TcsL plus α-chymotrypsin; lanes 5 and 10, TcsL plus V8 protease; and lanes 6 and 11, TcsL plus proteinase K. Lane 1 shows the molecular mass markers.

TcsL forms high-molecular-weight oligomeric structures at pH 8.0.

Interestingly, the intensity of the 45- to 55-kDa proteins present in the TcsL dissociated at pH 4.0 was higher than that expected if these proteins were derived from dissociation of TcsL alone. Among the possible explanations for the incongruent association between the intensity of the smaller bands and the levels of TcsL was that some of the 45- to 55-kDa proteins were derived from a larger complex not detected by standard SDS-10% PAGE. For this reason, we analyzed samples of TcsL for high-molecular-weight complexes (>750 kDa) by using SDS-AGE. As shown in Fig. 6A, a high-molecular-weight protein was observed in TcsL samples at pH 8.0 which also dissociated under pH 4.0 conditions similar to TcsL. Although TcsL reassembled when the sample was brought back to pH 8.0, this larger protein was not detected following the pH shift.

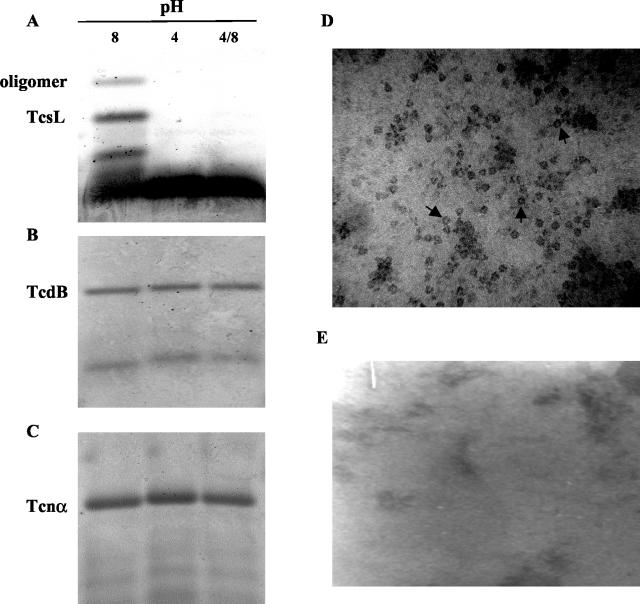

FIG. 6.

SDS-AGE analysis of TcsL, TcdB, and Tcnα and TEM analysis of TcsL. (A to C) Each respective toxin was separated by SDS-1.5% AGE following incubation under the indicated pH conditions. Each lane represents 15 μg of protein. TcsL at pH 8.0 (D) and pH 4.0 (E) was stained with PTA and subsequently analyzed by TEM at a magnification of ×105. Arrows indicate examples of oligomeric structures.

As shown in Fig. 6, high-molecular-weight proteins were not observed when two related LCTs, TcdB (Fig. 6B) and Tcnα (Fig. 6C), were subjected to the same pH conditions. Because high-molecular-weight proteins often represent the presence of oligomeric structures, TcsL was observed via TEM at pH 8.0 and pH 4.0. As shown in Fig. 6D, protein aggregates were observed in TcsL samples at pH 8.0, suggesting the formation of oligomers under these conditions. These oligomers, however, were not observed under pH 4.0 conditions (Fig. 6E), which supports the previous observations of the protein sample by SDS-PAGE.

These findings suggested that the larger protein complex might account for the protease resistance and protection to TcsL and is dissociated at pH 4.0. Based on this possibility, we predicted that TcsL would be unstable if it was not maintained in the complex. Thus, the protein mixture was resolved via SDS-PAGE, and the protein resolving at ∼280 kDa was electroeluted from the gel. In addition, the large protein complex was electroeluted following resolution by SDS-AGE. Both samples were then subsequently examined by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 7, following electroelution, TcsL spontaneously dissociated into the smaller 45- to 55-kDa proteins, similar to those observed following incubation at pH 4.0. Electroelution of the larger complex from SDS-AGE resulted in slight dissociation and the appearance of trace amounts of a protein resolving at the size of TcsL. Findings from the electroelution experiment indicate that TcsL outside of the larger complex is unstable and subject to degradation even under mild conditions. Furthermore, this analysis suggests that TcsL is part of the larger protein complex.

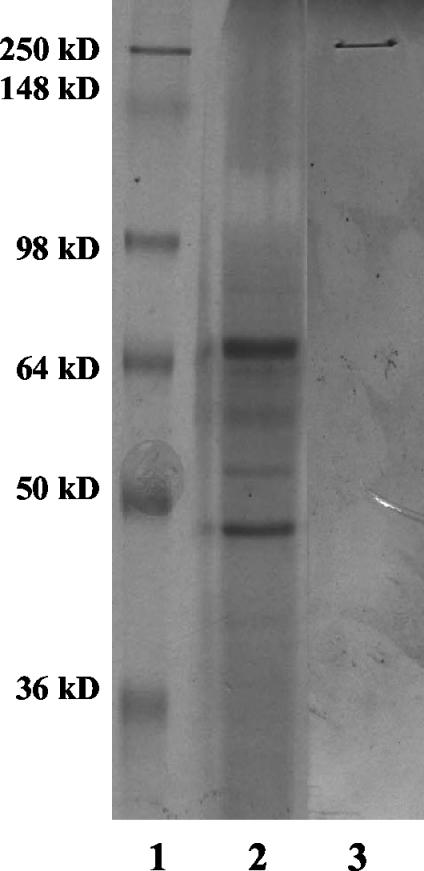

FIG. 7.

Electroelution of TcsL and TcsL complex proteins. Protein bands representing TcsL and the TcsL complex were subjected to electroelution in the presence of SDS for 2 h at room temperature. Following electroelution, proteins were separated via SDS-10% PAGE and observed by using Coomassie blue staining. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, protein electroeluted from TcsL; lane 3, protein electroeluted from the oligomer.

DISCUSSION

TcsL shares several common characteristics with other members of the LCT family of virulence factors. Among these attributes is the fact that TcsL is a notably large, single polypeptide relative to other bacterial toxins, that it acts as an intracellular toxin, and that it glycosylates small GTPases in order to alter target cell physiology. Yet, based on results from the present study, it appears that TcsL may be unique among the LCTs, as this toxin is maintained in a dissociable high-molecular-weight complex. Dissociation of this complex may be the major rate-limiting step in TcsL activity, and this barrier is overcome most effectively at acid pH. The need for dissociation of this complex prior to intoxication may explain results of a previous study (22) and the predictions of Chaves-Olarte et al. (8). Both studies suggested that TcsL's slow rate of inducing CPE was due to limitations at the point of cell entry.

Acid-induced activation is not uncommon to bacterial toxins; however, we believe the mechanism by which TcsL is activated at low pH is distinct from that described by other reports. For example, the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, listeriolysin O, produced by Listeria monocytogenes, is optimally active within the acidified endosome (21). Unlike TcsL, listeriolysin O is activated at low pH by direct conformational changes in the protein, which leads to more efficient membrane insertion, pore formation, and, possibly, protein stability. Yet, unlike TcsL, activation of listeriolysin O does not involve the dissociation of a multiprotein complex. Vacuolating cytotoxin from Helicobacter pylori is also reportedly activated by acid pH (17), but this differs in several ways from the activation of TcsL. Although vacuolating activity is enhanced at low pH, this does not apparently involve dissociation of a multimeric complex. Furthermore, unlike TcsL, the activation of vacuolating cytotoxin is not reversible, as shifting the protein sample back to pH 8.0 does not reduce activity.

In our experiments and in previous reports (20), TcsL was resistant to a wide variety of active proteases including trypsin, V8 protease, and α-chymotrypsin. Each of these proteases had little effect on TcsL activity, with only α-chymotrypsin reducing the rate of CPE. Proteinase K cleaved and inactivated TcsL, but this only occurred following extended incubations. TcsL and the 45- to 55-kDa proteins were susceptible to these proteases when not associated with the complex, further indicating that the high-molecular-weight complex provides protease resistance. In this way, TcsL is similar to botulinum toxin, which also resides in a multimeric complex. Similar to the TcsL complex, botulinum toxin exists in a high-molecular-weight aggregate that is highly resistant to multiple proteases (9). However, unlike the TcsL complex, the botulinum toxin complex does not dissociate under acidic conditions.

Recent studies by Pfeifer et al. indicate that TcdB is proteolytically processed while entering the cytosol of target cells in early endocytic vesicles (19). This was also shown to be directly related to acidification within early endosomes. Thus, TcdB processing and disassembly of the monomer are intimately linked to cell entry. Likewise, our model for TcsL indicates that the processing of the toxin may be necessary for intoxication. Yet dissociation of TcsL proceeds differently and, perhaps, at earlier stages than that found for TcdB. The present model suggests that TcsL dissociation requires extracellular low pH to enhance cytotoxicity through the breakdown of the high-molecular-weight complex. It is unclear whether this also leads to translocation of a fragment of the toxin into the cytosol as was reported for TcdB.

Investigations are under way to determine the mechanism behind multimer formation and acid pH-induced dissociation of the complex. It will be important to differentiate between the physical dissociation of the complex, proteolysis, and autocatalysis. As mentioned in Results, the inclusion of protease inhibitors does not alter the dissociation profile, suggesting this event may not result from the activation of proteases under acid pH conditions. Furthermore, spiking the sample with other proteins, such as bovine serum albumin, does not result in the degradation of these added proteins when the pH is lowered (data not shown). Thus, the present data indicate that protease activation is not a tenable explanation for dissociation of the complex. However, the sequence of the gene encoding TcsL indicates that this protein is expressed as a single polypeptide, suggesting that the protein must be proteolyzed at some point. Collectively, these data suggest two possibilities. First, the toxin copurifies with a protease that is highly specific for TcsL and is not blocked by protease inhibitors that are currently available. Alternatively, dissociation of the multimer is due to a yet undefined mechanism of autocatalysis. This would be in line with the findings on the light chain of botulinum toxin, where studies demonstrated that this polypeptide showed autocatalysis over an extended period of time at low pH (2).

The stability of the TcsL complex may influence C. sordellii disease. As one example, in a recent study of tissue from 795 donors, samples were analyzed for the presence of C. sordellii (15). Of these 795 donors, 8% were contaminated with Clostridia, and 37.7% of the organisms were found to be C. sordellii. Thus, contamination of allograft material by C. sordellii is a growing concern. Furthermore, approaches to decontaminate tissue prior to transplantation may also need to include methods to remove toxin. Indeed, TcsL's protease-resistant multimer may allow this toxin to be effective in a variety of environments and explain in part how C. sordellii is capable of causing such a broad range of diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence grant (1P20RR15564-01) and an Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology grant (HR 98-079) to J.D.B.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamkiewicz, T. V., D. Goodman, B. Burke, D. M. Lyerly, J. Goswitz, and P. Ferrieri. 1993. Neonatal Clostridium sordellii toxic omphalitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 12:253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, S. A., P. McPhie, and L. A. Smith. 2003. Autocatalytically fragmented light chain of botulinum A neurotoxin is enzymatically active. Biochemistry 42:12539-12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aktories, K., G. Schmidt, and I. Just. 2000. Rho GTPases as targets of bacterial protein toxins. Biol. Chem. 381:421-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amimoto, K., E. Oishi, H. Yasuhar, O. Sasak, S. Katayama, T. Kitajima, A. Izumida, and T. Hirahara. 2001. Protective effects of Clostridium sordellii LT and HT toxoids against challenge with spores in guinea pigs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 63:879-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boquet, P. 1999. Bacterial toxins inhibiting or activating small GTP-binding proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 886:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch, C., F. Hofmann, R. Gerhard, and K. Aktories. 2000. Involvement of a conserved tryptophan residue in the UDP-glucose binding of large clostridial cytotoxin glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13228-13234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch, C., F. Hofmann, J. Selzer, S. Munro, D. Jeckel, and K. Aktories. 1998. A common motif of eukaryotic glycosyltransferases is essential for the enzyme activity of large clostridial cytotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19566-19572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves-Olarte, E., M. Weidmann, C. Eichel-Streiber, and M. Thelestam. 1997. Toxins A and B from Clostridium difficile differ with respect to enzymatic potencies, cellular substrate specificities, and surface binding to cultured cells. J. Clin. Investig. 100:1734-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, F., G. M. Kuziemko, and R. C. Stevens. 1998. Biophysical characterization of the stability of the 150-kilodalton botulinum toxin, the nontoxic component, and the 900-kilodalton botulinum toxin complex species. Infect. Immun. 66:2420-2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gredlein, C. M., M. L. Silverman, and M. S. Downey. 2000. Polymicrobial septic arthritis due to Clostridium species: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:590-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmann, F., C. Busch, and K. Aktories. 1998. Chimeric clostridial cytotoxins: identification of the N-terminal region involved in protein substrate recognition. Infect. Immun. 66:1076-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karasawa, T., X. Wang, T. Maegawa, Y. Michiwa, H. Kita, K. Miwa, and S. Nakamura. 2003. Clostridium sordellii phospholipase C: gene cloning and comparison of enzymatic and biological activities with those of Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium bifermentans phospholipase C. Infect. Immun. 71:641-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeDell, K. H., R. Lynfield, R. N. Danila, and H. F. Hull. 2001. Unexplained deaths following knee surgery. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis, C. J., and R. D. Naylor. 1998. Sudden death in sheep associated with Clostridium sordellii. Vet. Rec. 142:417-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malinin, T. I., B. E. Buck, H. T. Temple, O. V. Martinez, and W. P. Fox. 2003. Incidence of clostridial contamination in donors' musculoskeletal tissue. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 85:1051-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez, R. D., and T. D. Wilkins. 1992. Comparison of Clostridium sordellii toxins HT and LT with toxins A and B of C. difficile. J. Med. Microbiol. 36:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClain, M. S., W. Schraw, V. Ricci, P. Boquet, and T. L. Cover. 2000. Acid activation of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) results in toxin internalization by eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 37:433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLauchlin, J., V. Mithani, F. J. Bolton, G. L. Nichols, M. A. Bellis, Q. Syed, R. P. Thomson, and J. R. Ashton. 2002. An investigation into the microflora of heroin. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:1001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeifer, G., J. Schirmer, J. Leemhuis, C. Busch, D. K. Meyer, K. Aktories, and H. Barth. 2003. Cellular uptake of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Translocation of the N-terminal catalytic domain into the cytosol of eukaryotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:44535-44541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popoff, M. R. 1987. Purification and characterization of Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin and cross-reactivity with Clostridium difficile cytotoxin. Infect. Immun. 55:35-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portnoy, D. A., V. Auerbuch, and I. J. Glomski. 2002. The cell biology of Listeria monocytogenes infection: the intersection of bacterial pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunity. J. Cell Biol. 158:409-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qa'Dan, M., L. M. Spyres, and J. D. Ballard. 2001. pH-enhanced cytopathic effects of Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin. Infect. Immun. 69:5487-5493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rorbye, C., I. S. Petersen, and L. Nilas. 2000. Postpartum Clostridium sordellii infection associated with fatal toxic shock syndrome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 79:1134-1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinave, C., G. Le Templier, D. Blouin, F. Leveille, and E. Deland. 2002. Toxic shock syndrome due to Clostridium sordellii: a dramatic postpartum and postabortion disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1441-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spyres, L. M., M. Qa'Dan, A. Meader, J. J. Tomasek, E. W. Howard, and J. D. Ballard. 2001. Cytosolic delivery and characterization of the TcdB glucosylating domain by using a heterologous protein fusion. Infect. Immun. 69:599-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vatn, S., O. V. Sjaastad, and M. J. Ulvund. 2000. Histamine in lambs with abomasal bloat, haemorrhage, and ulcers. J. Vet. Med. Ser. A 47:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vatn, S., M. A. Tranulis, and M. Hofshagen. 2000. Sarcina-like bacteria, Clostridium fallax and Clostridium sordellii in lambs with abomasal bloat, haemorrhage, and ulcers. J. Comp. Pathol. 122:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]