Abstract

Reactive oxygen species are a critical weapon in the killing of Aspergillus fumigatus by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), as demonstrated by severe aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease. In the present study, A. fumigatus-produced mycotoxins (fumagillin, gliotoxin [GT], and helvolic acid) are examined for their effects on the NADPH oxidase activity in human PMN. Of these mycotoxins, only GT significantly and stoichiometrically inhibits phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-stimulated O2− generation, while the other two toxins are ineffective. The inhibition is dependent on the disulfide bridge of GT, which interferes with oxidase activation but not catalysis of the activated oxidase. Specifically, GT inhibits PMA-stimulated events: p47phox phosphorylation, its incorporation into the cytoskeleton, and the membrane translocation of p67phox, p47phox, and p40phox, which are crucial steps in the assembly of the active NADPH oxidase. Thus, damage to p47phox phosphorylation is likely a key to inhibiting NADPH oxidase activation. GT does not inhibit the membrane translocation of Rac2. The inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation is due to the defective membrane translocation of protein kinase C (PKC) βII rather than an effect of GT on PKC βII activity, suggesting a failure of PKC βII to associate with the substrate, p47phox, on the membrane. These results suggest that A. fumigatus may confront PMN by inhibiting the assembly of the NADPH oxidase with its hyphal product, GT.

The best-known NADPH oxidase occurs in phagocytes and provides large quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to oxidatively modify microbes as a microbicidal mechanism. The phagocyte NADPH oxidase is a highly regulated multisubunit enzyme composed of p67phox, p47phox, p40phox, and Rac2 in the cytosol, as well as flavocytochrome b558, which consists of gp91phox and p22phox, in the membrane (4, 9, 15, 29, 36, 39, 57). The enzyme is dormant in resting cells, with these phox (for phagocyte oxidase) components being distributed to their cellular compartments. However, once phagocytes encounter invading microbes or soluble stimulants, such as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), cytosolic phox components and Rac2 migrate to the membrane to assemble with flavocytochrome b558, forming the active enzyme. The activated flavocytochrome b558 works as the catalytic redox center, where electrons are transferred from NADPH to molecular oxygen to generate O2−, a precursor of ROS. Recently, increasing attention has been directed toward the Nox/Duox family in nonphagocytes (33), which is composed of homologues of gp91phox. Although the rates of ROS production are quite low in nonphagocytes, their ROS are believed to play important roles in cell signaling, hypoxic response, the immune system, etc.

Over the past decade, the biochemistry of phagocyte NADPH oxidase has been intensively studied, particularly concerning the roles of Src homology 3 (SH3) domains and proline-rich regions (PRR), as well as those of other domains recently identified in the enzyme function (4, 9, 15, 29, 36, 39, 57). Molecular biology techniques have succeeded in relating their multiple interplay with not only activation (15, 36, 39, 57) but also down-regulation (21, 48) of the oxidase. However, little is known about how microbes attack the phagocyte NADPH oxidase to evade host defense, except for some recent reports regarding salmonellosis (23, 56) and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (5, 38).

In the present paper, we focus on the mechanisms of NADPH oxidase inhibition by gliotoxin (GT), a metabolite of pathogenic fungi, such as Candida and Aspergillus. Aspergillosis is a very serious opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients suffering from diseases such as cancer and AIDS (8, 16). The incidence of aspergillosis is second only to that of Candida infections, but it causes far higher mortality, with Aspergillus fumigatus being the most common isolate from these patients. Moreover, Aspergillus infection is frequent in patients with chronic granulomatous disease (11, 26, 49) who have a nonfunctional NADPH oxidase due to genetic defects in one of the phox components other than p40phox. This indicates that the extracellular ROS produced by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) is crucial for resistance to Aspergillus, since the hyphae are far larger than PMN.

It has been demonstrated in intact PMN that GT inhibits the activation of NADPH oxidase (61), but the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated. GT is a thiol-modifying toxin because of its disulfide bridge, typical of the epipolythiodioxopiperazine class of compounds (58). The importance of thiol groups for the function of phagocyte NADPH oxidase has been pointed out (4), since reagents, such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), p-chloromercuribenzoate, and phenylarsine oxide (PAO), efficiently inhibit O2− generation (1, 22, 32). NEM inhibits the catalysis of activated oxidase (1), as well as the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components (10). PAO, which reacts specifically with vicinal thiol groups in proteins, inhibits NADPH oxidase by interfering with oxidase activation rather than catalysis of the activated oxidase (32, 34). Unlike these chemical thiol modifiers, GT is a natural and biologically active metabolite that has actually been isolated from A. fumigatus-infected sites (6). In the present study, GT is shown to affect critical steps in the activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase, especially those required for assembly of the cytosolic components with the membrane-bound flavocytochrome b558.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pretreatment of PMN with mycotoxins produced by A. fumigatus.

Human PMN were isolated from either buffy coat residues or venous blood from healthy volunteers, in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at our institute, by Ficoll-Paque differential density centrifugation and 0.2% (wt/vol) methylcellulose sedimentation, as previously described (53). Unless otherwise indicated, the isolated PMN were first treated with 2 mM diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan) for 15 min on ice, washed, and finally suspended in cold Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM glucose (PBSG), pH 7.4. The PMN were then pretreated with the indicated amounts of A. fumigatus mycotoxins (fumagillin, GT, and helvolic acid, all from Sigma) for 5 to 10 min at 37°C in PBSG, washed three times, and finally resuspended in PBSG. GT and fumagillin were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and helvolic acid was dissolved in PBS by bringing the solution to pH 7 with 1 N NaOH. Matched control PMN were similarly treated with the same concentrations of DMSO or PBS-1N NaOH solvent. The order of DFP treatment (i.e., before or after GT treatment) made no difference in the inhibition of O2− generation by GT.

Subcellular fractionation of PMN.

PMN were pretreated with the desired concentrations of GT or its analogue, bis-dethio-bis(methylthio)-GT (dissolved in DMSO; Sigma) (abbreviated to dimethyl-GT below) (Fig. 1) at 0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 10 min at 37°C and washed three times with PBSG. They were then stimulated for 7 min at 37°C with 250 ng of PMA/2.5 × 106 cells/ml in PBSG containing 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM NaN3. Matched control PMN were similarly treated with the same concentrations of DMSO solvent in place of the mycotoxins and PMA, respectively. After being washed once with 5 volumes of iced PBSG, the PMN were resuspended at 5 × 107 cells/ml and disrupted by sonication on ice in buffer A {100 mM KCl, 3 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)], pH 7.3} containing 10 μM leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF. All subsequent steps to prepare the membrane and cytosol fractions were carried out as previously described (54, 55). Briefly, the sonicates were spun at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C to obtain their postnuclear supernatants. These fractions were then separated into membranes and cytosol at 200,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C (Beckman TLA-45 rotor), and the membranes were resuspended in the initial volumes of buffer A. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Lowry using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

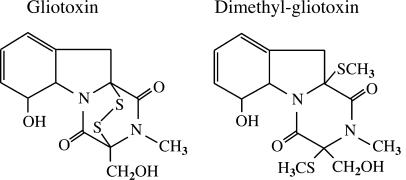

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of GT and dimethyl-GT (an S-methylated metabolite of GT).

Protein phosphorylation and immunoprecipitation.

The loading of 32PO4 was carried out essentially as previously reported (47). Isolated PMN in PBSG were washed twice with loading buffer (137 mM NaCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 5.6 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), suspended at 107 cells/ml, and then treated with 5 mM DFP for 20 min on ice. After being washed once, the cells were resuspended at 108 cells/ml in the loading buffer supplemented with 1 mCi of 32PO4/ml (DuPont-NEN, Boston, Mass.). 32PO4 loading was continued for 90 min at 25°C with intermittent brief mixing every 15 min. The loaded PMN were pelleted and aliquoted to 0.25 × 107 cells/ml in the loading buffer supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM CaCl2. After treatment with 10 μg of GT/0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 10 min at 37°C, the PMN were stimulated with 250 ng of PMA for 5 min at 37°C and spun at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, following a fivefold dilution with iced loading buffer. Cell lysis was carried out for 30 min on ice in 1.6 ml of cell lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1% [wt/vol] NP-40, and 2.5% [wt/vol] glycerol in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) (28) containing a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 125 nM okadaic acid, and 1 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate). This cell lysis buffer solubilizes the cytosolic phox components that have migrated to the membrane. The cell lysates were spun at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were divided into two aliquots (0.8 ml each) and subjected to immunoprecipitation, one with combined antibodies against p67phox and p40phox and the other with an antibody against p47phox. After immunoblot analysis, radioactive bands on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) sheets were quantified using a bio-image analyzer (Fuji BAS2000; Fuji Photofilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and expressed as photostimulative luminescence (PSL) counts.

Preparation of PMN cytoskeletal fraction.

The effect of GT on cytoskeletal localization of cytosolic phox components was evaluated using the Triton X-100 method, basically as reported previously (55). In brief, PMN treated with 5 mM DFP were pretreated with 10 μg of GT/0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 10 min at 37°C and washed twice with PBSG. The PMN were then stimulated with 1 μg of PMA/107 cells/ml in PBSG containing 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM NaN3 for 7 min at 37°C. After being washed once with 5 volumes of iced PBSG, the PMN were resuspended at 6 × 107 cells/100 μl in Triton X-100 lysis buffer (1% [wt/vol] Triton X-100 in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 5 mM EGTA, 0.25 mM leupeptin, and 1 mM DFP) and then sonicated for 10 s at 70-W output on ice. After standing for 10 min on ice, the sonicates were loaded on top of 0.3 ml of 6% (wt/vol) sucrose in the Triton X-100 lysis buffer and spun at 109,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C. The top 100 μl and the pellet, resuspended in the initial volume of 0.4 ml, were used as Triton X-100-soluble (Sol) and -insoluble (Skl) fractions, respectively.

Immunoblot analysis.

Detection of the NADPH oxidase components was performed as previously reported (37, 54, 55). Antibodies against either the C- or N-terminal polypeptides of p67phox, p47phox, p40phox, and p22phox were raised in rabbits. A goat anti-rp47phox antibody was a generous gift of H. Malech (National Institutes of Health), and a rabbit anti-Rac2 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.). A rabbit anti-protein kinase C (PKC) βII antibody was raised against the human C-terminal polypeptide (positions 661 to 673). Subcellular fractions were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the proteins were then transferred to PVDF sheets. After being blocked with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk in PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20, the separated proteins (except Rac2 and PKC βII) were probed with the respective primary antibodies and the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, both at 1:1,000 dilution, followed by development with o-dianisidine. For Rac2 detection, PVDF sheets were first blocked in the presence of skim milk, followed by probing with the primary (1:200 dilution) and secondary (1:1,000 dilution) antibodies in its absence. For PKC βII detection, after blocking with skim milk, probing was done with its primary antibody (1:500 dilution) in 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin and with the secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) in skim milk. Their immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)-plus reagents (Amersham Bioscience Corp., Piscataway, N.J.). Where indicated, the membrane translocation of PKC βII was analyzed with a 420oe scanner (Arcus II; PDI Inc., Huntington Station, N.Y.).

In vitro phosphorylation of p47phox by PKC βII.

Recombinant p47phox was purified from Sf9 cells infected with baculoviruses containing its cDNA, a generous gift from J. Lambeth (Emory University, Atlanta, Ga.), to a single band after Coomassie blue staining on SDS-PAGE. Ten picomoles of rp47phox and 0.3 U (0.106 pmol) of rPKC βII (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) were pretreated for 5 min at 37°C with either GT or PAO in 20 μl of buffer A. Phosphorylation of rp47phox was started by the addition of 10 μl of cocktail (1 mM ATP, 4 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 μg of phosphatidylserine, and 0.1 μg of diolein). The lipids were added as liposomes, prepared by dissolving them in chloroform, drying them under a stream of nitrogen, and sonicating the dried lipids for 3 min in buffer A. The 30-μl final reaction mixture was further incubated for 30 min at 37°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Radioactive bands were finally detected using a bio-image analyzer after the immunoblot analysis of rp47phox.

NADPH oxidase assay.

NADPH oxidase activity was quantified by the rate of superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable ferricytochrome c reduction by O2−, using a dual-wavelength spectrophotometer recording ΔA550-540 (Hitachi 557). The oxidase activity of intact cells was determined by the O2− generation stimulated with 100 ng of PMA/106 cells/ml; the oxidase activity of membranes was measured after adding 0.2 mM NADPH (37, 55). At maximal velocity, 200 U of SOD/ml was added to determine the net cytochrome c reduced by O2−.

RESULTS

Effects of A. fumigatus mycotoxins on O2− generation in intact PMN.

First, we screened A. fumigatus-produced mycotoxins (fumagillin, GT, and helvolic acid) for their effects on PMA-stimulated O2− generation. Of these, GT (Fig. 1) was the only mycotoxin that had a deleterious effect on O2− generation (Fig. 2A). When PMN were pretreated with GT for 7 min at 37°C, the O2− generation was dose-dependently reduced, even after the PMN were washed free of GT. GT up to ∼2 μg/ml was almost innocuous, but the O2− generation started to fall quickly from that point, and a concentration as low as 8 μg/ml was completely inhibitory in the pretreatment of 0.25 × 107 cells. Although the effects of GT on cell functions have been discussed in terms of concentration in previous reports, it became evident here that GT stoichiometrically inhibits PMA-stimulated O2− generation: the 50% inhibitory concentration rose ∼4-fold (from 2.95 to 11.0 μg/ml) for the quadrupled cell numbers (1.0 × 107 cells) (Fig. 2A). This stoichiometric inhibition was also apparent even with a 1-min treatment at 37°C, showing that GT quickly enters the cell to react with intracellular constituents. This speed was not affected so much by lowering the incubation temperature to 25 or 4°C (data not shown). The inhibition by 10 μg of GT/ml on O2− generation was not associated with PMN death under such conditions, as far as tested by trypan blue dye exclusion.

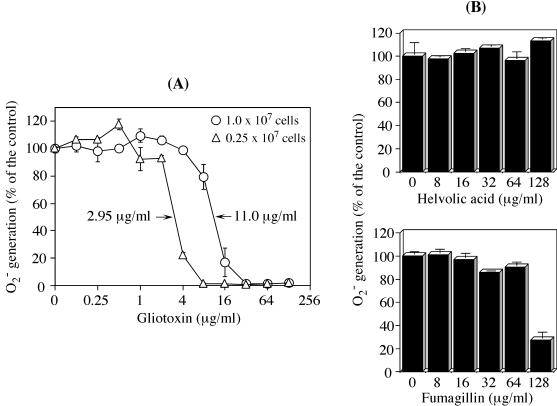

FIG. 2.

Stoichiometric GT-induced inhibition of O2− generation in PMN. (A) PMN were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of GT at either 1.0 × 107 or 0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 7 min at 37°C. After they were washed, their O2− generation was evaluated by SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction following PMA stimulation (100 ng of PMA/106 cells/ml). (B) PMN (0.05 × 107 cells/ml) were pretreated in a cuvette for 5 min at 37°C with either helvolic acid or fumagillin and directly subjected to the cytochrome c assay without being washed. The data represent the means ± standard deviations of five (A) and two (B) experiments done in duplicate and are expressed as percentages of the O2− generated by control PMN pretreated with the respective solvents.

GT at 8 μg/ml induces 100% inhibition in 0.25 × 107 cells (Fig. 2A). One-fifth of the PMN (0.05 × 107 cells) were preincubated with either helvolic acid or fumagillin in cuvettes for 5 min at 37°C and then stimulated with PMA without washing the cells (Fig. 2B). Considering the ratio of mycotoxin to cells in a volume of 1 ml, 64 μg of helvolic acid or fumagillin for 0.05 × 107 cells is equivalent to 320 μg of GT for treating 0.25 × 107 cells. Unlike GT, however, neither mycotoxin was inhibitory even at this high concentration. This conclusion was unchanged even when the differences in the molecular weights of helvolic acid (568.7), fumagillin (458.6), and GT (326.4) were considered. For fumagillin, a concentration of 128 μg/ml was inhibitory, perhaps due to a direct toxicity to PMN. Subsequent GT treatments of PMN were carried out at a concentration of 10 μg of GT/0.25 × 107 cells/ml.

GT inhibits the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components, but not Rac2, in PMA-stimulated PMN.

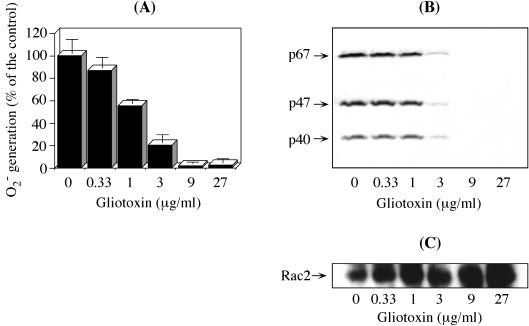

The activation of NADPH oxidase requires the assembly of membrane-integrated flavocytochrome b558 with cytosolic components (10). Therefore, to gain insight into the mechanism by which GT inhibits O2− generation, we first analyzed the effect of GT on the subcellular distribution of the oxidase components by immunoblot analysis. In resting PMN, the cytosolic phox components p67phox, p47phox, and p40phox are located only in the cytosol. In contrast, stimulation with PMA causes the membrane translocation of these phox components (10, 53, 55). The control membrane fraction from PMA-stimulated PMN retained a full set of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 3B; 0 μg of GT/ml) and was endowed with high O2−-generating activity (Fig. 3A; 100% = 15.0 ± 1.4 nmol/min/mg of protein). Pretreatment of PMN with the indicated concentrations of GT, however, caused a dose-dependent decrease in the oxidase activity recovered in membranes, with very little activity at ≥9 μg/ml. In addition, the degrees of oxidase inhibition (Fig. 3A) were highly correlated with the membrane translocation levels of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 3B). In contrast, GT did not inhibit the membrane translocation of Rac2 (Fig. 3C), which was rather increased with higher GT concentrations. Equivalent amounts of membranes in the fractions were confirmed by immunoblotting with an anti-p22phox antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Correlation between GT-induced inhibition of O2− generation and membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components. PMN (0.25 × 107 cells/ml) were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of GT for 7 min at 37°C, washed, and stimulated with 250 ng of PMA/2.5 × 106 cells/ml for 7 min at 37°C, and finally, their membranes were fractionated. (A) O2− generation was initiated by adding 0.2 mM NADPH to the membrane aliquots (0.05 × 107 cell equivalents) and determined as SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction. The data are the means ± standard deviations of four experiments done in duplicate. (B and C) Aliquots (0.05 × 107 cell equivalents) of the same membrane fractions were subjected to immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods. Reacted HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were developed with o-dianisidine (B) and ECL-plus (C). The data are representative of three (B) and four (C) experiments.

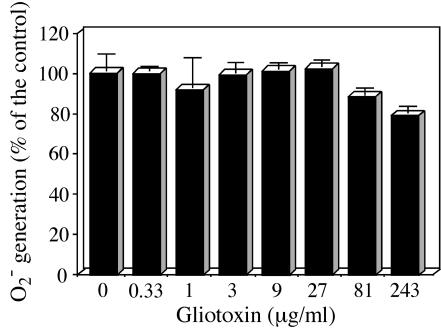

Next, we investigated whether GT directly inhibits the assembled active NADPH oxidase (Fig. 4). Aliquots of 30 μg of membrane proteins (corresponding to 0.05 × 107 cell equivalents) from PMA-stimulated PMN were individually incubated under the indicated GT concentrations for 5 min before their O2−-generating activities were measured. Since the amount of membrane corresponded to 0.05 × 107 cell equivalents, the indicated GT doses were virtually fivefold higher than those in the cell treatment experiments (0.25 × 107 cells) (Fig. 3A). GT, however, failed to show inhibition up to 27 μg/ml. A slight inhibition was induced at the extremely high concentration of 81 (88.6% ± 3.3%) or 243 (79.5% ± 3.3%) μg/ml (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Postaddition effect of GT on PMA-stimulated membranes. Membranes from PMA-stimulated PMN not treated with GT (0 μg/ml in Fig. 3) were used to examine the postaddition effect of GT. Aliquots (0.05 × 107 cell equivalents) were pretreated in cuvettes with the indicated concentrations of GT for 5 min at room temperature. The effect on O2− generation was then determined as described for Fig. 3A. The data show the means ± standard deviations of two experiments done in duplicate.

These results indicate that the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components, excluding Rac2, is involved in the inhibitory process of GT at the cellular level. Once the active oxidase is assembled, however, GT can no longer affect enzyme catalysis.

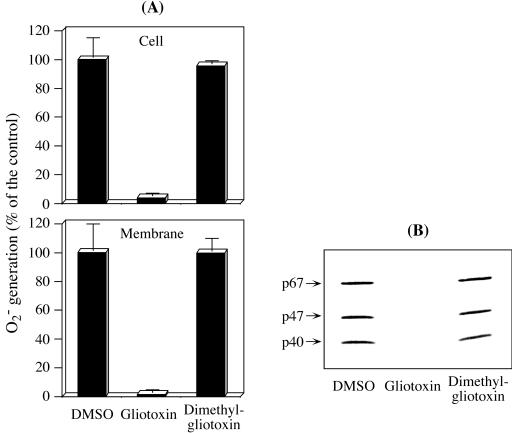

The disulfide bridge of GT is crucial to prevent the assembly of active NADPH oxidase.

To assess the importance of the disulfide bridge of GT in the loss of NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 2), we tested dimethyl-GT (Fig. 1), in which the disulfide bridge is irreversibly modified by methylation. Dimethyl-GT is a metabolite of GT present in A. fumigatus culture (2). PMN treatment with 10 μg of GT/ml impeded nearly all of the O2− generation in whole cells (3.91 ± 2.0%) and their fractionated membranes (1.5 ± 2.1%) (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, dimethyl-GT did not cause any inhibitory effect on O2− generation in either intact cells (95.5% ± 2.3%) or membranes (99.6% ± 9.1%). The values in parentheses show the percentages relative to the DMSO-treated control cells (12.8 ± 1.8 nmol/min/107 cells) and their membranes (23.0 ± 4.3 nmol/min/mg protein), respectively. The membrane translocation profiles of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 5B) correlated well with those of O2− generation. Thus, the use of dimethyl-GT clearly demonstrated that the characteristic disulfide bridge of GT is crucial for affecting the assembly of active NADPH oxidase.

FIG. 5.

Effects of the GT analogue, dimethyl-GT, on O2− generation and membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components. PMN were pretreated with either GT or its analogue, dimethyl-GT, at 10 μg/0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 10 min at 37°C. After being washed, a portion of the PMN (106 cells) were analyzed for O2− generation (A, top). The remaining PMN were subjected to subcellular fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. The O2− generation of membrane fractions (A, bottom) and membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components (B) were then evaluated in the same way as for Fig. 3. The data in panel A show the means ± standard deviations of two experiments done in duplicate. Panel B is representative of two reproducible experiments.

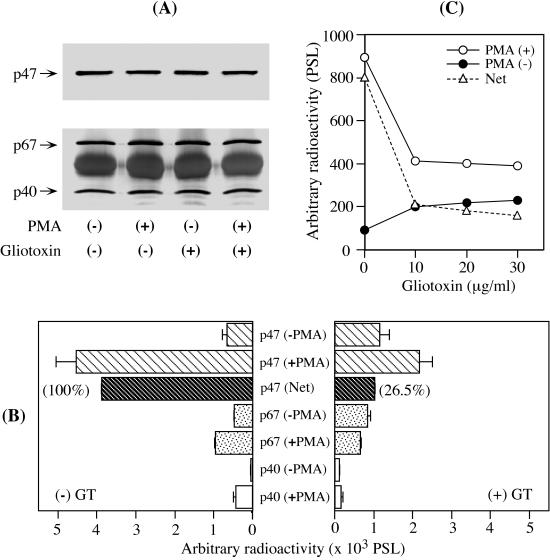

GT inhibits the PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of p47phox.

A large number of reports have demonstrated that the phosphorylation of p47phox is an essential step in the activation of NADPH oxidase (4, 9, 15, 18, 29, 36, 39, 47, 57). Here, we investigated the effects of GT on the phosphorylation of the entire population of cytosolic phox components that migrated to the membrane or remained in the cytosol. For this purpose, 32PO4-loaded PMN were stimulated with PMA, lysed in cell lysis buffer, and subsequently immunoprecipitated with the individual antibodies against p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox (see Materials and Methods). Immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitates revealed the presence of p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox in equivalent amounts in all cases, regardless of whether the cells were stimulated with PMA or pretreated with GT (Fig. 6A). Broad bands over an ∼50-kDa region (Fig. 6A, bottom) were due to the heavy chain of rabbit immunoglobulin G used for the immunoprecipitation. Because the molecular weight of p47phox falls within this region, a goat instead of a rabbit anti-p47phox antibody was used for immunoprobing (Fig. 6A, top). These immunoblotted sheets were subsequently subjected to autoradiography. P47phox from resting PMN had little 32P incorporated (Fig. 6B, left, first upper bar). In contrast, the phosphorylation of p47phox was augmented 6.9-fold by a 5-min stimulation with PMA (Fig. 6B, left, second upper bar). GT treatment at 10 μg/ml, however, caused substantial inhibition (Fig. 6B, right, second upper bar). Comparing the background PSL counts in the absence of PMA stimulation, GT by itself tended to induce phosphorylation of p47phox (Fig. 6B, left, first upper bar, versus right, first upper bar). Therefore, the effect of GT on PMA-stimulated p47phox phosphorylation was evaluated after subtracting the respective background PSL counts. The subtracted net values showed a remarkable inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation: 26.5% at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 6B, right), 22.5% at 20 μg/ml, and 20.2% at 30 μg/ml (Fig. 6C). The last two values indicate that 10 μg of GT/ml was sufficient to nearly saturate the inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation for 0.25 × 107 cells, as was the case for O2− generation and membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 2, 3, and 5). Looking at p67phox and p40phox, it seems that GT prevented their PMA-stimulated phosphorylation (Fig. 6B, compare +PMA bars on the left and right). However, since GT itself similarly increased background PSL counts (Fig. 6B, compare −PMA bars on the left and right) and the degrees of PMA-stimulated phosphorylation were far lower than that of p47phox, the effects of GT on p67phox and p40phox remain inconclusive. The results obtained here, however, unequivocally show that GT affects the step of p47phox phosphorylation, playing a central role in the assembly of catalytic NADPH oxidase. GT increases cyclic AMP levels and protein kinase A activity in cells (59). Thus, the PMA-independent phosphorylation of cytosolic phox components by GT itself (Fig. 6B) might be assigned to a protein kinase A-catalyzed route, which is known to exist in PMN (19, 31).

FIG. 6.

Effect of GT on PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of cytosolic phox components. After a 10-min pretreatment with 10 μg of GT/0.25 × 107 cells/ml at 37°C, 32PO4-loaded PMN were stimulated with 250 ng of PMA/2.5 × 106 cells/ml for 5 min at 37°C. The PMN were then lysed and immunoprecipitated with rabbit antibodies against cytosolic phox components (see Materials and Methods). (A) They were individually immunoprobed with primary antibodies produced in a goat (p47phox) and rabbits (p67phox and p40phox), followed by the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and developed with o-dianisidine. (B) The same PVDF sheets were analyzed using a bio-image analyzer. The radioactivities of the respective immunoblot bands are expressed as PSL counts. The data are the means ± standard deviations of two experiments done in duplicate. (C) 32PO4-loaded PMN were similarly pretreated with the indicated concentrations of GT and subjected to the same procedures as in panels A and B for p47phox detection. The PSL counts in p47phox bands from PMN stimulated (+) with PMA and unstimulated (−) and the net values (Net) are shown.

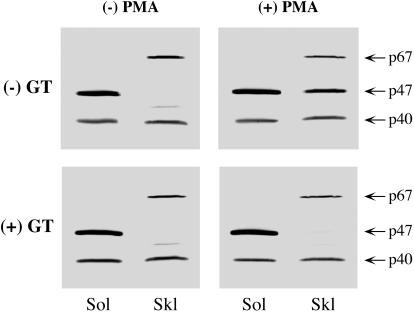

GT prevents the incorporation of p47phox in the cytoskeletal fraction.

NADPH oxidase and the cytoskeleton in PMN have a very close relationship, and the O2−-generating activity of stimulated PMN is recovered exclusively in the cytoskeletal fraction (40, 55, 60). In resting PMN, almost all p67phox associates with the cytoskeleton. In contrast, p47phox is fully separated from the cytoskeleton but is incorporated into the cytoskeletal fraction upon cell stimulation, following the phosphorylation of C-terminal serines between S303 and S379 (18).

We treated PMN with Triton X-100 to investigate the influence of GT on the distribution of cytosolic phox components between the cytoskeletal (Skl) and noncytoskeletal (Sol) fractions. A Triton X-100 insoluble fraction is generally taken as the cytoskeleton, and noncytoskeletal substances are recovered in the Triton X-100 soluble fraction. PMN not treated with GT showed results consistent with earlier reports (40, 55, 60): in resting cells, p47phox and p67phox localized exclusively in the noncytoskeletal and cytoskeletal fractions, respectively, and p40phox was almost equally distributed in both fractions (Fig. 7, upper left). Following PMA stimulation, some soluble p47phox moved to the cytoskeletal fraction (Fig. 7, upper right). A 10-min pretreatment of PMN with 10 μg of GT/ml, however, completely abolished the PMA-stimulated incorporation of p47phox into the cytoskeletal fraction (Fig. 7, lower right). This treatment affected neither p40phox nor p67phox distribution in the resting PMN, as well as in the PMA-stimulated PMN.

FIG. 7.

Effect of GT on the distribution of cytosolic phox components to Sol and Skl fractions. PMN were pretreated with 10 μg of GT/0.25 × 107 cells/ml for 10 min at 37°C. After being washed, the PMN were stimulated (+) with 1 μg of PMA/107 cells/ml for 7 min at 37°C or left unstimulated (−) and were then subjected to Sol and Skl fractionation (see Materials and Methods). Equivalent amounts (106 cell equivalents) of both fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting plus developing with o-dianisidine as described for Fig. 3. The data are representative of five reproducible experiments.

Phosphorylation in the C-terminal region during PMN stimulation imparts a conformational change to p47phox (35, 51, 57), which allows the association with p67phox in the cytoskeleton. Thus, p47phox was probably unable to be incorporated into the cytoskeletal fraction because of the inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation caused by GT.

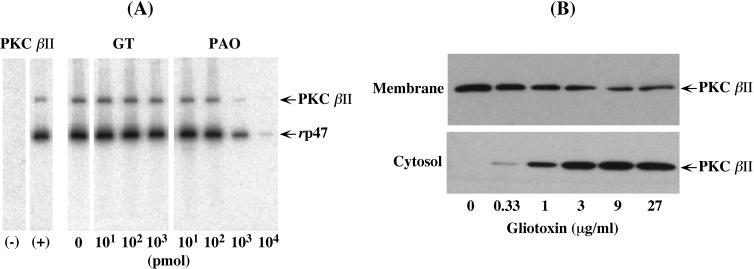

GT inhibits the membrane translocation of PKC βII, but not its activity.

Human PMN express five PKC isoforms: α, βI, βII, δ, and ζ (13, 27). Recent studies have shown that PKC β, particularly PKC βII, is preferentially involved in the PMA-stimulated activation of NADPH oxidase (14, 30). We thus investigated whether GT affects the PKC βII activity to phosphorylate p47phox in vitro. In Fig. 8A, the two left lanes show that rp47phox was phosphorylated in a PKC βII-dependent manner. The upper phosphorylated band is attributed to the autophosphorylated PKC βII (41). Contrary to our expectation, however, GT did not show direct inhibition of PKC βII activity, even at a concentration as high as 103 pmol (16.3 μg/ml) (Fig. 8A). This concentration exceeds the critical 8 to 9 μg of GT/ml which allowed the nearly complete inhibition of membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components, as well as O2− generation (Fig. 2 and 3). Thus, it could be concluded that GT has no inhibitory activity, not only on PKC βII but also on p47phox itself. In contrast, PAO, which reacts with vicinal thiol groups (50), began to affect PKC βII activity at 103 pmol (8.4 μg/ml) and showed almost complete inhibition at 104 pmol (84 μg/ml). Intriguingly, in contrast to the lack of effect on PKC βII activity, GT decreased the PMA-stimulated membrane translocation of PKC βII (Fig. 8B, top). This effect of GT was saturated at 9 μg/ml, and a concentration of 27 μg/ml did not show further inhibition (for quantitative details, see the legend to Fig. 8B). The smaller content of PKC βII in the membranes was in good agreement with the lowering of p47phox phosphorylation in Fig. 6C, showing that PKC βII may account for the majority of p47phox phosphorylation. Taken together, these results suggest that the inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation by GT in intact PMN could result from its failure to associate with PKC βII on the membrane.

FIG. 8.

Effects of GT on PKC βII activity and its membrane translocation. (A) In the two left lanes, rp47phox (10 pmol) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the absence (−) or presence (+) of rPKC βII (0.106 pmol) in a 10-μl cocktail containing 1 mM ATP (4 μCi of [γ-32P]-ATP), as described in Materials and Methods. The reactions were stopped with Laemmli sample buffer and subjected to bio-image analysis after SDS-PAGE. For the analysis of the GT or PAO effect, the mixtures of rp47phox and rPKC βII were pretreated for 5 min at 37°C with the indicated amounts of GT or PAO before the phosphorylation was started. (B) PMA-stimulated subcellular fractions were prepared from GT-treated PMN in the same way as for Fig. 3. Aliquots of membrane (106 cell equivalents) and cytosol (106 cell equivalents) fractions were subjected to immunoblotting and ECL-plus developing (for details, see Materials and Methods). The levels of membrane translocation of PKC βII decreased to 55, 46, 34, 19, and 22% of the control (0 μg of GT/ml), respectively, as the GT concentration increased. The experiments were repeated four (A) and three (B) times with similar results.

DISCUSSION

Inhibition of the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components, but not Rac2.

The hyphae of A. fumigatus release a number of low-molecular-weight toxins, especially fumagillin, GT, and helvolic acid (3). Although fumagillin and helvolic acid both cause cilioinhibitory effects on human respiratory epithelia in vitro at concentrations above 1 μg/ml and cause complete ciliostasis at 10 μg/ml (2), their effects on O2− generation were diametrically opposed here. Helvolic acid was completely ineffective in inhibiting PMA-stimulated O2− generation (0.05 × 107 cells with no washing), while fumagillin caused 72.7% inhibition only at the high concentration of 128 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). This inhibition by fumagillin may be due to a direct toxicity to PMN. In contrast, GT significantly and stoichiometrically inhibited the PMA-stimulated O2− generation, which quickly fell with the 50% inhibitory concentrations of 2.95 (0.25 × 107 cells) and 11.0 (1.0 × 107 cells) μg/ml (Fig. 2), suggesting that a threshold of intracellular GT is required to inhibit NADPH oxidase activation. Such levels of GT are attainable in vivo: a reported A. fumigatus-infected tissue containing 9.2 mg of GT/kg (6) gives >10 μg/ml in situ, a level found here to completely suppress NADPH oxidase activation.

The inhibition by GT was clearly shown to be due to the defective membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components: the degrees of oxidase inhibition in membranes were well correlated with the levels of inhibition in the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 3B). Once the NADPH oxidase was activated, however, GT was no longer effective (Fig. 4), suggesting that GT-sensitive thiol groups are masked in the activated oxidase. In contrast to GT, its metabolite, dimethyl-GT, was unable to inhibit both the O2− generation and the membrane translocation of cytosolic phox components (Fig. 5), proving that the disulfide bridge of GT is essential for its inhibitory activity.

In contrast, GT did not impede the membrane translocation of Rac2 but rather increased it (Fig. 3C). This finding probably reflects the fact that Rac2 in the cytosol translocates to the membrane simultaneously with, but independently of, the cytosolic phox components, an event that is also essential for the activation of NADPH oxidase (17, 24).

Inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation.

GT inhibited the PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of p47phox (Fig. 6). The phosphorylation of p47phox is a prominent event upon PMN stimulation that is primarily important in initiating its translocation to the membrane and in assembling the active NADPH oxidase complex (4, 9, 15, 29, 36, 39, 57). PMA is a direct stimulator of PKC, for which p47phox is an excellent substrate, rendering p47phox capable of supporting O2− generation even under cell-free activation conditions (45). In addition, a direct association of p47phox with PKC βII has recently been proven in stimulated cells (30, 46). Thus, the inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation by GT may be attributed to an effect on PKC, or on p47phox itself, since the latter effect may change its tertiary structure as a PKC substrate (see below).

Inhibition of p47phox incorporation into the cytoskeletal fraction.

Previous work has suggested a close association between NADPH oxidase and the PMN cytoskeleton (40, 55, 60). In resting cells, p47phox is entirely free from the cytoskeleton, whereas p67phox is totally associated with it. P47phox is in a closed inactive conformation: its N-terminal SH3 domain is masked via an intramolecular interaction with its C-terminal PRR (35, 51). Upon cell stimulation, p47phox is phosphorylated and incorporated into the cytoskeleton, following the association of its C-terminal PRR with the C-terminal SH3 domain of p67phox. Finally, the p47phox that is anchoring p67phox targets the PRR in the p22phox subunit of flavocytochrome b558 to become membrane associated (4, 9, 15, 29, 36, 39, 57). This association of p47phox with flavocytochrome b558 probably ensures the membrane translocation of p67phox, and p40phox as well. Thus, the multiple effects of GT on p47phox, specifically related to phosphorylation (Fig. 6), incorporation into the cytoskeletal fraction (Fig. 7), and translocation to the membrane (Fig. 3 and 5), suggest that the inhibition of p47phox phosphorylation is crucial for the subsequent steps required for oxidase activation.

Inhibition of membrane translocation of PKC βII, but not its activity.

PMN contain 5 of the 11 known isoforms of PKC (13, 27). These comprise three conventional isoforms, α, βI, and βII; one novel isoform, δ; and one atypical isoform, ζ. These PKC isoforms are able to phosphorylate p47phox and induce O2− generation in the cell-free system using recombinant cytosolic components (20). The affinity of PKC α for p47phox is, however, quite low compared to those of other isoforms, and atypical PKC ζ, which lacks a phorbol ester-binding domain, is insensitive to PMA (12). Furthermore, PKC δ is unlikely to be involved in the cytoskeletal incorporation of p47phox (43), as well as in its phosphorylation (46). Recently, PKC β was shown to be important in PMA-stimulated activation of the oxidase by using PMN from PKC β knockout mice (14). The essential role of PKC βII rather than PKC βI was further demonstrated by antisense depletion studies of PKC βII (30). Also, the major kinase capable of binding p47phox in PMA-stimulated cytosol was found to be PKC, particularly PKC βII, but not p21-activated kinase or mitogen-activated protein kinase (46).

Hence, we examined in the present study whether GT affects in vitro p47phox phosphorylation by PKC βII. Contrary to our expectation, however, GT did not affect p47phox phosphorylation (Fig. 8A). This result suggests that GT is ineffective not only in inhibiting the PKC βII activity itself but also in causing the deterioration of p47phox as a PKC βII substrate. In contrast, PAO, which specifically interacts with vicinal thiol groups, impaired p47phox phosphorylation. PAO probably inhibited the PKC βII activity by interfering with vicinal cysteines 70 and 71 in a cysteine-rich zinc finger sequence (42), the phorbol ester binding domain (44).

Although it did not affect PKC βII activity, GT did inhibit its translocation to the membrane (Fig. 8B) through a mechanism that is presently unknown. However, based on the notion that spatial regulation of signaling components is critical in the concerted assembly and activation of NADPH oxidase, the following speculation seems plausible. Three direct interactions have been reported between (i) PKC βII and F-actin (7), (ii) p47phox and actin (52), and (iii) p47phox and PKC βII (46). These interactions provide the idea that in stimulated PMN, an actin filament scaffold serves to colocalize p47phox and PKC βII in close proximity, where the PMA-activated PKC βII should then phosphorylate p47phox. The phosphorylated p47phox will bring p67phox and p40phox, and maybe also PKC βII, to the membrane through the association with flavocytochrome b558, as discussed above. GT might affect the association of PKC βII with p47phox on this actin-based scaffold. In this regard, effects of GT not only on actin but also on STCKs (substrates that interact with C kinase), which localize to interfaces between membranes and cytoskeletal structures and serve in cytoskeletal remodeling (25), may not be excluded.

For a long time, the phagocyte O2−-generating enzyme has been known to be highly sensitive to covalent thiol-modifying reagents, such as NEM, but it has not been described in terms of targeting by pathogens. GT, having a disulfide bridge, is expected to oxidize neighboring thiol groups in cellular proteins through mixed disulfide formation and thus to inactivate them if the groups are located at an active site. In the present study, we demonstrated that the inhibition of O2− generation by GT in whole PMN could be explained mainly by abrogated p47phox phosphorylation, a key step for the activation of the respiratory burst. Conversely, PMN confront pathogens by producing O2− through the one-electron reduction of oxygen by NADPH oxidase. These are battles between pathogens (GT) and hosts (ROS originating from O2−) using oxidoreducing reactions to impose oxidative stress on each other. The assessment of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase from such a point of view may provide new insights into the etiology of invasive aspergillosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and from the Human Science Research Foundation, Japan.

We are grateful to J. D. Lambeth for providing us with cDNA for rp47phox and H. L. Malech for a goat anti-rp47phox antibody.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Akard, L. P., D. English, and T. G. Gabig. 1988. Rapid deactivation of NADPH oxidase in neutrophils: continuous replacement by newly activated enzyme sustains the respiratory burst. Blood 72:322-327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amitani, R., G. Taylor, E. N. Elezis, C. Llewellyn-Jones, J. Mitchell, F. Kuze, P. J. Cole, and R. Wilson. 1995. Purification and characterization of factors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus which affect human ciliated respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 63:3266-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arruda, L. K., B. J. Mann, and M. D. Chapman. 1992. Selective expression of a major allergen and cytotoxin, Asp f I, in Aspergillus fumigatus. Implications for the immunopathogenesis of Aspergillus-related diseases. J. Immunol. 149:3354-3359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babior, B. M. 1999. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 93:1464-1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee, R., J. Anguita, D. Roos, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Cutting edge: infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by down-regulating gp91phox. J. Immunol. 164:3946-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer, J., M. Gareis, A. Bott, and B. Gedek. 1989. Isolation of a mycotoxin (gliotoxin) from a bovine udder infected with Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 27:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blobe, G. C., D. S. Stribling, D. Fabbro, S. Stabel, and Y. A. Hannun. 1996. Protein kinase C βII specifically binds to and is activated by F-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15823-15830. (Erratum, 271:30297.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodey, G. P. 1988. The emergence of fungi as major hospital pathogens. J. Hosp. Infect. 11(Suppl. A):411-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark, R. A. 1999. Activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase. J. Infect. Dis. 179:S309-S317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark, R. A., B. D. Volpp, K. G. Leidal, and W. M. Nauseef. 1990. Two cytosolic components of the human neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase translocate to the plasma membrane during cell activation. J. Clin. Investig. 85:714-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curnutte, J. T. 1992. Disorders of granulocyte function and granulopoiesis, p. 904-937. In N. Oski (ed.), Hematology of infancy and childhood, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 12.Dang, P. M., A. Fontayne, J. Hakim, J. El Benna, and A. Périanin. 2001. Protein kinase C ζ phosphorylates a subset of selective sites of the NADPH oxidase component p47phox and participates in formyl peptide-mediated neutrophil respiratory burst. J. Immunol. 166:1206-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang, P. M., J. Hakim, and A. Périanin. 1994. Immunochemical identification and translocation of protein kinase C zeta in human neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 349:338-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekker, L. V., M. Leitges, G. Altschuler, N. Mistry, A. McDermott, J. Roes, and A. W. Segal. 2000. Protein kinase C-β contributes to NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils. Biochem. J. 347:285-289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeo, F. R., and M. T. Quinn. 1996. Assembly of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: molecular interaction of oxidase proteins. J. Leukoc. Biol. 60:677-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denning, D. W., S. E. Follansbee, M. Scolaro, S. Norris, H. Edelstein, and D. A. Stevens. 1991. Pulmonary aspergillosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 324:654-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dusi, S., M. Donini, and F. Rossi. 1996. Mechanisms of NADPH oxidase activation: translocation of p40phox, Rac1 and Rac2 from the cytosol to the membranes in human neutrophils lacking p47phox or p67phox. Biochem. J. 314:409-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Benna, J., L. P. Faust, and B. M. Babior. 1994. The phosphorylation of the respiratory burst oxidase component p47phox during neutrophil activation. Phosphorylation of sites recognized by protein kinase C and by proline-directed kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 269:23431-23436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Benna, J., R. P. Faust, J. L. Johnson, and B. M. Babior. 1996. Phosphorylation of the respiratory burst oxidase subunit p47phox as determined by two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C, protein kinase A, and a mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6374-6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontayne, A., P. M. Dang, M. A. Gougerot-Pocidalo, and J. El-Benna. 2002. Phosphorylation of p47phox sites by PKC α, βII, δ, and ζ: effect on binding to p22phox and on NADPH oxidase activation. Biochemistry 41:7743-7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs, A., M. C. Dagher, J. Fauré, and P. V. Vignais. 1996. Topological organization of the cytosolic activating complex of the superoxide-generating NADPH-oxidase. Pinpointing the sites of interaction between p47phox, p67phox and p40phox using the two-hybrid system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 5:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabig, T. G., and B. A. Lefker. 1985. Activation of the human neutrophil NADPH oxidase results in coupling of electron carrier function between ubiquinone-10 and cytochrome b559. J. Biol. Chem. 260:3991-3995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallois, A., J. R. Klein, L. A. Allen, B. D. Jones, and W. M. Nauseef. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J. Immunol. 166:5741-5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyworth, P. G., B. P. Bohl, G. M. Bokoch, and J. T. Curnutte. 1994. Rac translocates independently of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase components p47phox and p67phox. Evidence for its interaction with flavocytochrome b558. J. Biol. Chem. 269:30749-30752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaken, S., and P. J. Parker. 2000. Protein kinase C binding partners. Bioessays 22:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston, R. B., Jr. 2001. Clinical aspects of chronic granulomatous disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 8:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kent, J. D., S. Sergeant, D. J. Burns, and L. C. McPhail. 1996. Identification and regulation of protein kinase C-δ in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 157:4641-4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knaus, U. G., S. Morris, H. J. Dong, J. Chernoff, and G. M. Bokoch. 1995. Regulation of human leukocyte p21-activated kinases through G protein-coupled receptors. Science 269:221-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi, T., S. Tsunawaki, and H. Seguchi. 2001. Evaluation of the process for superoxide production by NADPH oxidase in human neutrophils: evidence for cytoplasmic origin of superoxide. Redox Rep. 6:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korchak, H. M., and L. E. Kilpatrick. 2001. Roles for βII-protein kinase C and RACK1 in positive and negative signaling for superoxide anion generation in differentiated HL60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8910-8917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer, I. M., R. L. van der Bend, A. J. Verhoeven, and D. Roos. 1988. The 47-kDa protein involved in the NADPH:O2 oxidoreductase activity of human neutrophils is phosphorylated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase without induction of a respiratory burst. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 971:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutsumi, H., K. Kawai, R. B. Johnston, Jr., and K. Rokutan. 1995. Evidence for participation of vicinal dithiols in the activation sequence of the respiratory burst of human neutrophils. Blood 85:2559-2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambeth, J. D. 2002. Nox/Duox family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) oxidases. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 9:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Cabec, V., and I. Maridonneau-Parini. 1995. Complete and reversible inhibition of NADPH oxidase in human neutrophils by phenylarsine oxide at a step distal to membrane translocation of the enzyme subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270:2067-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leto, T. L., A. G. Adams, and I. de Mendez. 1994. Assembly of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: binding of Src homology 3 domains to proline-rich targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10650-10654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leusen, J. H., A. J. Verhoeven, and D. Roos. 1996. Interactions between the components of the human NADPH oxidase: intrigues in the phox family. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 128:461-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizunari, H., K. Kakinuma, K. Suzuki, H. Namiki, T. Kuratsuji, and S. Tsunawaki. 1993. Nucleoside-triphosphate binding of the two cytosolic components of the respiratory burst oxidase system: evidence for its inhibition by the 2′,3′-dialdehyde derivative of NADPH and desensitization in their translocated states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1220:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mott, J., Y. Rikihisa, and S. Tsunawaki. 2002. Effects of Anaplasma phagocytophila on NADPH oxidase components in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells. Infect. Immun. 70:1359-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nauseef, W. M. 1999. The NADPH-dependent oxidase of phagocytes. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 111:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nauseef, W. M., B. D. Volpp, S. McCormick, K. G. Leidal, and R. A. Clark. 1991. Assembly of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase. Protein kinase C promotes cytoskeletal and membrane association of cytosolic oxidase components. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5911-5917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton, A. C. 1995. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28495-28498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishizuka, Y. 1988. The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature 334:661-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nixon, J. B., and L. C. McPhail. 1999. Protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms translocate to Triton-insoluble fractions in stimulated human neutrophils: correlation of conventional PKC with activation of NADPH oxidase. J. Immunol. 163:4574-4582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ono, Y., T. Fujii, K. Igarashi, T. Kuno, C. Tanaka, U. Kikkawa, and Y. Nishizuka. 1989. Phorbol ester binding to protein kinase C requires a cysteine-rich zinc-finger-like sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4868-4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, J. W., C. R. Hoyal, J. E. L. Benna, and B. M. Babior. 1997. Kinase-dependent activation of the leukocyte NADPH oxidase in a cell-free system. Phosphorylation of membranes and p47PHOX during oxidase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11035-11043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves, E. P., L. V. Dekker, L. V. Forbes, F. B. Wientjes, A. Grogan, D. J. Pappin, and A. W. Segal. 1999. Direct interaction between p47phox and protein kinase C: evidence for targeting of protein kinase C by p47phox in neutrophils. Biochem. J. 344:859-866. (Erratum, 345:767, 2000.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rotrosen, D., and T. L. Leto. 1990. Phosphorylation of neutrophil 47-kDa cytosolic oxidase factor. Translocation to membrane is associated with distinct phosphorylation events. J. Biol. Chem. 265:19910-19915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sathyamoorthy, M., I. de Mendez, A. G. Adams, and T. L. Leto. 1997. p40phox down-regulates NADPH oxidase activity through interactions with its SH3 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9141-9146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Segal, B. H., E. S. DeCarlo, K. J. Kwon-Chung, H. L. Malech, J. I. Gallin, and S. M. Holland. 1998. Aspergillus nidulans infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine 77:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stockton, L. A., and R. H. S. Thompson. 1946. British Anti-Lewisite 1. Arsenic derivatives of thiol proteins. Biochem. J. 40:529-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sumimoto, H., Y. Kage, H. Nunoi, H. Sasaki, T. Nose, Y. Fukumaki, M. Ohno, S. Minakami, and K. Takeshige. 1994. Role of Src homology 3 domains in assembly and activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5345-5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamura, M., T. Kai, S. Tsunawaki, J. D. Lambeth, and K. Kameda. 2000. Direct interaction of actin with p47phox of neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276:1186-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsunawaki, S., H. Mizunari, H. Namiki, and T. Kuratsuji. 1994. NADPH-binding component of the respiratory burst oxidase system: studies using neutrophil membranes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease lacking the β-subunit of cytochrome b558. J. Exp. Med. 179:291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsunawaki, S., S. Kagara, K. Yoshikawa, L. S. Yoshida, T. Kuratsuji, and H. Namiki. 1996. Involvement of p40phox in activation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase through association of its carboxyl-terminal, but not its amino-terminal, with p67phox. J. Exp. Med. 184:893-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsunawaki, S., and K. Yoshikawa. 2000. Relationships of p40phox with p67phox in the activation and expression of the human respiratory burst NADPH oxidase. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 128:777-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vazquez-Torres, A., Y. Xu, J. Jones-Carson, D. W. Holden, S. M. Lucia, M. C. Dinauer, P. Mastroeni, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science 287:1655-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vignais, P. V. 2002. The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase: structural aspects and activation mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1428-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waring, P., R. D. Eichner, and A. Müllbacher. 1988. The chemistry and biology of the immunomodulating agent gliotoxin and related epipolythiodioxopiperazines. Med. Res. Rev. 8:499-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waring, P., T. Khan, and A. Sjaarda. 1997. Apoptosis induced by gliotoxin is preceded by phosphorylation of histone H3 and enhanced sensitivity of chromatin to nuclease digestion. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17929-17936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woodman, R. C., J. M. Ruedi, A. J. Jesaitis, N. Okamura, M. T. Quinn, R. M. Smith, J. T. Curnutte, and B. M. Babior. 1991. Respiratory burst oxidase and three of four oxidase-related polypeptides are associated with the cytoskeleton of human neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 87:1345-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshida, L. S., S. Abe, and S. Tsunawaki. 2000. Fungal gliotoxin targets the onset of superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268:716-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]