Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effect of clinical and laboratory manifestations, and medication prescribing, on survival according to patient age at diagnosis in a large academic systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) cohort.

METHODS

We identified SLE patients with a diagnosis at age ≥ 18, seen between 1970 through 2011, and with more than 2 visits to our lupus center. Data collection included SLE manifestations, serologies, other laboratory tests, medications, dates and causes of death. We examined characteristics of those diagnosed before age 50 (adult-onset) compared to those diagnosed at or after age 50 (late-onset) using descriptive statistics. We used Kaplan Meier curves with log rank tests to estimate five- and ten-year survival in age-stratified cohorts. Predictors of ten-year survival were assessed using Cox regression models, adjusted for calendar year, race/ethnicity, sex, lupus nephritis and medication use.

RESULTS

Of 928 SLE patients, the mean age at diagnosis was 35. Among the adult-onset group, there was significantly higher prevalence of malar rashes and lupus nephritis. Glucocorticoids, azathioprine, mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide use were also more frequently in the adult-onset group compared to the late-onset group. Five-year survival rates were 99.5% and 94.9% and ten-year survival rates were 97.8% and 89.5%, among those diagnosed before and at or after age 50. In the entire cohort, increasing age at diagnosis, male sex and Black race were statistically significant predictors of reduced ten-year survival. Compared to those diagnosed before age 50, the late-onset group had a multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for ten- year risk of death of 4.96 (95% CI 1.75–14.08). The most frequent cause of known death was a lupus manifestation, followed by cardiovascular disease and infection.

CONCLUSIONS

In our cohort, several demographic features, SLE manifestations, and medication prescribing differed between those with adult-onset and late-onset SLE. Ten-year survival rates were high for both groups, but relatively lower among late-onset patients. A lupus manifestation as the cause of death was more common among adult-onset compared with late-onset patients.

Keywords: SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus), Survival Mortality, Outcomes, Age, Male

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous autoimmune disease of unknown etiology and variable clinical severity. SLE may follow a relatively benign course or a rapidly progressive and severe clinical path, leading to organ failure and death. Reports of survival rates have varied over the past 50 years and with geographic location, with improved survival reported in recent years (1–4). The nature and severity of SLE and its manifestations may vary by age. While SLE predominantly affects women in their 20s and 30s, disease severity and manifestations have been shown to differ between early-onset and late-onset disease (11–15). A few cohort studies have specifically investigated ‘late-onset SLE’, defined by diagnosis at or after age 50, and reported different demographic and clinical features in these patients compared to those of younger patients, and much poorer survival (15,19,20). Past cohort studies have also reported that Asian, Hispanic and African American groups, in general, have, higher mortality and more severe disease than whites (5–10). Male patients, in general, are thought to have more severe disease and worse prognosis than female patients (10, 16).

The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Lupus Center has maintained a detailed and updated registry containing data on all individuals seen for potential SLE since 1970. These data offer the opportunity to evaluate the characteristics of patients diagnosed before compared to at or after age 50, and to investigate variation in and predictors of survival among SLE patients. Our goals were to investigate differences in clinical manifestations, medication prescription, and survival among SLE patients according to their age at diagnosis.

Methods

Study Population

Our Lupus Center is the largest academic center for care of SLE in New England and patients seen there include primary, secondary and tertiary referrals, and are generally followed in our care. All new patients seen in the Lupus Center who have received a billing code for SLE since 1970 have had their medical records reviewed in detail for American College of Rheumatology criteria for the Classification of SLE, as well as other signs and symptoms and laboratories and the rheumatologist’s diagnosis and are added to the registry prospectively. Data collected includes these data from the time they were first seen, including SLE manifestations through that time, date of diagnosis and basic demographic information, as well as data collected from their individual medical records to obtain medication, serologic and clinical data at all time points available in our system as they were followed over time. The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Lupus Registry contains data on 1278 patients seen in our Lupus Center with SLE per treating rheumatologist and SLE expert reviewer’s opinion, and ≥ 4/11 of the 1997 ACR Criteria for Classification of SLE (17). For this study, we identified patients in our Registry who had a validated date of diagnosis between January 1, 1970 and April 30, 2011, age ≥ 18 at diagnosis, and ≥ 2 visits to our center. We included patients diagnosed as adults, as prior studies have established poorer outcomes among children with SLE and our focus was on the differences between late-onset disease and earlier onset adult disease {Amador-Patarroyo, 2012 #1261; Hersh, 2009 #1266; Tucker, 2008 #1263}. SLE patients under the age of 18 were also excluded from the study as the care of children with SLE has changed over time and, including a local shift in care from our institution to Boston Children’s Hospital.

Data Collection

Detailed data have been collected prospectively in the BWH Lupus Registry, including date of birth, date of SLE diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, SLE clinical manifestations and serologies, and the treating rheumatologist’s and the SLE expert reviewer’s diagnosis. Additionally, we supplemented and updated these data using electronic and paper medical record reviews. We queried the Partners’ Healthcare System Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR), which captures nearly five million unique patients and contains a warehouse of over one billion inpatient and outpatient observations from Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both of which are Harvard-affiliated teaching hospitals and major tertiary referral centers in the New England area. RPDR contains data as far back as 1980 and was used to identify patient demographics, laboratory tests, medications, and dates of death (via the Social Security Death Index). Data, including cause of death, were also ascertained manually from detailed medical record reviews. Data collection in sum included age at SLE diagnosis, past clinical manifestations of SLE, SLE serologies, hematologic and renal laboratories, medication prescriptions (hydroxychloroquine, systemic glucocorticoids- oral and intravenous, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and leflunomide – all ever/never), and dates and causes of death. The Partners’ Healthcare Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study.

Statistical Analyses

We divided the cohort into two groups, those diagnosed before age 50 and those diagnosed at or after age 50. Descriptive statistics including t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to evaluate clinical characteristics of patients in each group and the Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons (18).

In survival analyses, Kaplan Meier curves with log rank tests were employed to test for differences in five and ten year survival between the two SLE groups. Multivariable Cox regression models, adjusted for calendar year, sex, race/ethnicity, presence of lupus nephritis, and immunosuppressant, glucocorticoid and hydroxychloroquine use, were used to estimate relative hazards of death within five and ten years of diagnosis in the two groups. We performed sensitivity analyses, in which individuals who were lost to follow-up (no documented death within the time period, but no further visits for a period of >2 years) were censored. Logistic regression analyses were used to investigate potential predictors of mortality in each group. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (Version 9.3, Cary, NC).

Results

Our analyses included 928 patients with SLE, divided into two age groups by SLE diagnosis age: 18–49 years (n=795) and 50 years and older (n=133). The mean age of diagnosis in the adult-onset group was 31.4 and in the late-onset group was 57.7 years. Demographic characteristics of note include the percentage of male patients, which was higher (14.3% vs. 6.7%) in the older diagnosis age group. Race/ethnicity demographics were similar in the two groups. There were significantly higher proportions of subjects in the younger age at diagnosis group who had malar rash (p<0.006) and lupus nephritis (p<0.0001), than in the older age at diagnosis group (where p for significance defined as p<0.003 after Bonferroni correction). Hydroxychloroquine use was over 80% in both diagnosis age groups, and glucocorticoid use was also high at over 69% in both groups. Receipt of glucocorticoids (p<0.0004), azathioprine (p<0.0008), mycophenolate (p<0.0006) and cyclophosphamide (p<0.00001) were more frequent in the younger-onset group compared to the late-onset group.

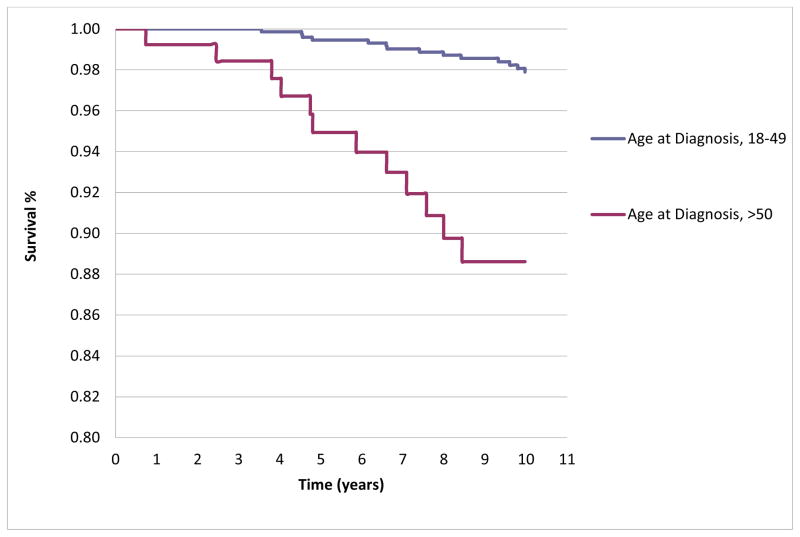

The overall mean follow-up of all patients in the cohort was 9.76 years (±6.7); the mean follow-up of patients under 50 years old at diagnosis was 9.88 years (±6.73), and 9.04 years (±6.14) for patients age 50 and over at diagnosis. The mean number of visits per patient was 19.6 (± 17.4) in those diagnosed at < 50 years of age, and 15.8 (±12.3) among those diagnosed at age 50 or older. The numbers of individuals lost to follow-up (no documented death within the time period, but no further visits for a period of >two years) for our five year survival analysis was 64 (6.9%) and for the ten year analysis was 146 (15.7%). There were ten deaths within five years of diagnosis: four in the adult-onset group and six in the late-onset group. There were 26 deaths within ten years of diagnosis in the entire cohort: 14 among the younger age at diagnosis group and 12 among the older age at diagnosis group. The five year survival rates were 99.5% and 94.9% among those diagnosed < and > age 50 (log rank p <0.0001) and the ten year survival rates were 97.8% and 89.5%, (log rank p<0.001). The Kaplan Meier curves for ten-year survival in the two age at diagnosis groups are shown in Figure 1. In sensitivity analyses censoring those lost to follow-up (assuming death, not survival), the analyses were quite similar: five year survival rates were 99.4% in the younger age at diagnosis group and 94.5% in the older age at diagnosis group, and ten year survival rates were 97.7% and 87.1%.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Curve demonstrating 10-year survival, by Age Group at Diagnosis

Compared to the younger diagnosis age group, the older diagnosis age group had a five year hazard ratio (HR) of 5.22 (95% CI 1.07, 25.36) and a ten year HR for death of 4.96 (95%CI 1.75–14.08), in multivariable Cox regression models adjusted for calendar year, sex, race/ethnicity, lupus nephritis and medication use. Again, in sensitivity analyses censoring those lost to follow-up, the analyses were quite similar: five year HR of 5.21 (95% CI 1.07, 25.36) and a ten year HR for death of 5.33 (95% CI 1.10–25.85). Predictors of reduced ten-year survival in the entire cohort, both unadjusted as well as adjusted for calendar year, race/ethnicity and medication use are shown in Table 1. They included increasing age at diagnosis (HR 1.07 per year of age), male sex and Black race. Other variables, including demographics, specific SLE manifestations (in particular lupus nephritis), and medication use were associated with neither improved nor reduced ten-year survival. There was neither improved nor reduced survival in analyses stratified by age at diagnosis (data not shown).

Table 1.

Cox Regression Models for 10-year Survival in BWH Lupus Cohort

| Unadjusted Hazard Ratio for Death (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio for Death (95% CI) a | |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing Age at Diagnosis, per year of age | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) |

| Sex | - | - |

| Female | Ref. | Ref |

| Male | 4.64 (1.98–10.874) | 5.10 (1.51–17.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref. | Ref. |

| Black | 2.65 (1.07–6.58) | 2.22 (0.75–6.63) |

| Hispanic | 6.16 (1.72–22.12) | 2.10 (0.25–17.54) |

| Asian | 2.68 (0.85–8.43) | 2.15 (0.53–8.62) |

| Lupus Nephritis | 0.82 (0.36–1.86) | 0.90 (0.29–2.82) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.95 (0.28–3.25) | 0.97 (0.25–3.70) |

| Glucocorticoids | 1.01 (0.30–3.48) | 0.67 (0.18–2.55) |

| Immunosuppressants | 1.45 (0.66–3.19) | 1.54 (0.52–4.55) |

Multivariable model including: age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, hydroxychloroquine, glucorticoid use, immunosuppressant use (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, leflunomide, methotrexate, rituximab) and calendar year

Table 2 describes the causes for 22 of the 26 deaths that occurred within ten years of diagnosis in this cohort. (Cause of death was not identified for four patients). Cause of death categories were broken into SLE-related, infection, cardiovascular disease, malignancy and other. This group of patients had severe SLE and most had other severe comorbid conditions. Overall, the causes of death among this group of patients included complications of SLE, such as end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis, pneumonitis and seizure. Infection, cardiovascular disease and malignancies were also common causes of death. Of those with a cause of death secondary to an SLE manifestation, there were higher numbers of events in the younger than older age at diagnosis groups. Although small numbers, infection and cardiovascular disease deaths were more common among older age at diagnosis patients and there were more malignancy related deaths among the younger age group.

Table 2.

Causes of Death among SLE patients who died within 10 years of diagnosis

| Age at Diagnosis | Sex | Race/Ethnicity | Age at Death | SLE Duration, years | Cause of Death and Relevant Co-morbidities a | Cause of death category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 50 at Diagnosis | ||||||

| 18.6 | F | Hispanic | 24.7 | 6.2 | Lupus nephritis with ESRD on HD, catastrophic pulmonary hemorrhage | SLE Manifestation |

| 22.5 | F | Black | 27.0 | 4.6 | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | Other |

| 28.4 | F | Black | 33.0 | 4.6 | Lupus nephritis with ESRD, APLA with CVA, complicated by endocardial abscess, sepsis | Infection |

| 29.2 | F | White | 39.2 | 10.0 | Vasculitis, Evans’ syndrome, substance abuse-> hypoxic respiratory failure thought secondary to lupus pneumonitis | SLE Manifestation |

| 29.4 | F | Other | 36.1 | 6.7 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 29.9 | F | Asian | 33.4 | 3.6 | Sickle cell, pulmonary hypertension | Other |

| 33.4 | F | Asian | 40.8 | 7.4 | LE nephritis with ESRD, Hepatitis C infection | SLE Manifestation |

| 33.6 | F | Other | 42.0 | 8.5 | LE nephritis with ESRD on HD, severe valvular disease and low ejection fraction/failure -> arrhythmia | Cardiovascular |

| 33.9 | F | White | 43.2 | 9.4 | HIV/AIDS, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Pneumocystis infection | Other |

| 35.9 | F | Hispanic | 45.5 | 9.7 | Metastatic breast cancer | Malignancy |

| 38.7 | F | Black | 48.5 | 9.8 | Pulmonary hypertension/COPD, CVA | Other |

| 41.4 | F | Asian | 49.3 | 8.0 | Metastatic cervical cancer | Malignancy |

| 41.8 | F | Black | 48.3 | 6.6 | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung transplant, SLE- related seizures leading to emesis and aspiration | SLE Manifestation |

| 42.4 | F | White | 47.2 | 4.8 | SLE recurrent seizures | SLE Manifestation |

| Age > 50 at Diagnosis | ||||||

| 50.2 | F | Asian | 57.8 | 7.6 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 52.1 | M | White | 52.8 | 0.7 | Coronary artery disease, SLE/Scleroderma overlap, mitral regurgitation, peripheral vascular | Cardiovascular |

| 52.4 | F | Black | 59.5 | 7.1 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 53.9 | F | Black | 60.5 | 6.6 | Lupus nephritis with ESRD; sepsis | Infection |

| 58.2 | M | White | 66.2 | 8.0 | Cardiomyopathy, APLA | Cardiovascular |

| 58.9 | F | White | 63.7 | 4.8 | Gastrointestinal bleeding and seizures (both SLE-related) | SLE Manifestation |

| 59.1 | M | Black | 63.1 | 4.1 | SLE with myositis, cardiomyopathy with heart failure, ESRD -> sepsis | Infection |

| 60.2 | F | Black | 68.6 | 8.5 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 61.5 | M | White | 66.3 | 4.8 | Bacterial/fungal sepsis | Infection |

| 63.5 | M | White | 67.3 | 3.8 | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Malignancy |

| 75.6 | M | White | 81.5 | 5.9 | CAD, aortic stenosis: died from complications following cardiac surgery | Cardiovascular |

| 82.3 | F | White | 84.8 | 2.5 | Hepatorenal syndrome | Other |

Abbreviations:

APLA = anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome

CAD=coronary artery disease

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CVA=cerebrovascular accident

ESRD = end-stage renal disease

HD= hemodialysis

Discussion

In this large cohort of SLE patients followed in the Northeastern U.S. since 1970, overall five and ten year survival rates were excellent (all > 89%), but higher among those patients diagnosed before age 50 compared to those diagnosed at or after age 50. Among those diagnosed at age 50 or older, there was a higher proportion of male patients compared to the under 50 diagnosis age group, confirming diminishing gender bias in SLE with age. SLE manifestations varied by age at diagnosis with malar rash and lupus nephritis being more common among those with younger age at diagnosis. Glucocorticoids, azathioprine, mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide use were also more frequently in the adult-onset group compared to the late-onset group. Despite the higher proportion of patients with lupus nephritis, survival rates for the younger age at diagnosis group were excellent and overall survival was not associated with the presence of lupus nephritis or other SLE manifestations or medication use. Among those who died within ten years of diagnosis, the most frequent known cause of death was lupus-related among younger patients and cardiovascular or infectious among older patients. Predictors of reduced ten-year survival included male sex, increasing age at diagnosis and Black race.

Past studies from other academic groups have sought to determine the differences that exist between patients who are diagnosed at younger compared to older ages with SLE. In a Chinese cohort of 158 patients, Lin et al. explored the survival rate and risk factors of mortality in patients with SLE onset after age 50(19). They reported that hematologic and renal involvement were found among this group to be the most common organ systems of involvement, while CNS involvement was relatively rare and most deaths were caused by infection. In that study, as in ours, increasing age at SLE onset was an independent risk factor for mortality. However, in the Chinese cohort, the ten year survival rate was only 56.5%. Alonso et al. also evaluated SLE with diagnosis after age 50 within a small cohort of 51 Spanish patients(15). As in our study, they reported that the proportion of women in the older onset group was lower than that in earlier-onset SLE. They found that nephritis was less common among patients with older age of diagnosis, as we have found, but also described an increased incidence of serositis that we have not observed. In our larger cohort and in contrast to Alonso et al, we found no association with anti-dsDNA antibodies in later-onset disease. Most recently, Tomic-Lucic et al evaluated 30 late-onset SLE patients in Serbia (age>50), matched to 30 SLE patients with earlier onset disease(20). They reported a lower rate of photosensitivity, and neuropsychiatric disease in the late-onset group, whereas we found no difference in these manifestations between age groups. Similar to our study, they documented a higher rate of malar rash and nephritis among younger age at diagnosis patients.

We found that predictors of reduced ten-year survival included male sex, increasing age at diagnosis and Black race. Renau and Isenberg performed a retrospective study of 484 patients (439 female, 45 male) to differentiate features of male versus female lupus among SLE patients seen at a single center in London (21). They found relatively few differences between men and women with regard to clinical and serologic features or outcomes among the patients in their group. In contrast, we have demonstrated that male sex is a significant predictor of reduced ten-year survival, in line with the findings of other groups, which have shown that rates of organ damage and disease severity are higher among male patients (10, 16). Renal disease was reported as the most important predictor of mortality within the SLE damage index by Danila et al among patients in a large multiethnic US cohort (22). We did not find nephritis, however, to be a predictor of ten-year mortality.

While survival rates are high in our cohort, the causes of death among SLE patients are similar to those reported earlier studies. In 1976, Urowitz et al described a bimodal mortality pattern of SLE. In that study, the patients who died shortly within three years of diagnosis were serologically and clinically active and their deaths were attributed to SLE manifestations (mostly nephritis) and sepsis. Patients who died later in the course of their disease had inactive lupus and several had myocardial infarctions(23). Based on a different study design of ten year survival in our cohort, causes of death within 10 years were mostly represented by an SLE manifestation directly, infection, cardiovascular disease or malignancy. Of those with a cause of death secondary to an SLE manifestation, there were higher numbers of events in the younger than older age at diagnosis groups. Although numbers were small, infection and cardiovascular disease deaths were more common among older age at diagnosis patients and there were more malignancy related deaths among the younger age group.

Alarcon et al described features and predictors of five-year mortality in the LUMINA cohort, where the majority of deaths were attributed directly to SLE and infections (24). We were able to distinguish earlier age at diagnosis patients as having more lupus-related causes of death than older patients. Also, infection and cardiovascular-disease related deaths were more common among older age at diagnosis patients when evaluating ten year survival, than in the younger age at diagnosis group.

Our five year survival rates were 99.5% and 95.5%, ten-year survival rates were 98.2% and 91%, among those diagnosed before and after age 50, representing rates similar to and even higher than those in reports from recent years. Reported five and ten year survival rates in other cohorts range from both less than 50% in 1955, to 92% and 83%, respectively, in 2003 (1–4, 25). Strengths of our study include data from a high volume Lupus Center in a large, academic medical center in New England with a diverse patient population and several decades of follow-up. There was no loss to follow-up for deaths as we captured all deaths in the U.S., using the National Social Security death index.

We limited the number of patients in our registry to those with confirmed SLE according to ACR criteria in the Registry and with ≥ two follow-up visits to insure more complete data collection. Among the resulting 928 patients, the mean follow-up time was 9.8 years, allowing an accurate assessment of the medical record during this time, with access to medication and cause of death data.

Limitations of this study include the inability to determine all co-morbidities. Given the retrospective nature of data collection, we were unable to accurately calculate SLE disease activity. We also acknowledge that there may have been changes to medications or co-morbidities outside of our hospital electronic medical record. While we have accurate data about ever/never medication exposure, it was not possible for us to accurately capture the exact dates of all medication exposures or cumulative medication doses from the medical records.

In summary, we describe differing demographic characteristics of SLE patients diagnosed at earlier vs. older age of onset: malar rash, lupus nephritis, as well as steroid, azathioprine, mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide use were more common among SLE patients diagnosed before age 50 compared to those 50 and older. Ten-year survival rates were very high for both groups, with a younger age of diagnosis associated with a slightly higher ten-year survival. Predictors of reduced survival included increasing age at diagnosis, male sex, Black race and the adjusted hazard ratio of death for patients ages 50 and older was 4.96 compared to patients diagnosed at a younger adult age with SLE. Among patients who died within ten years of diagnosis, lupus manifestations were more likely to be the cause of death in younger than older onset disease patients.

Key Messages.

In our cohort, older age at SLE diagnosis tended to be a group with relatively more male patients. Younger age at diagnosis was associated with malar rash, lupus nephritis and greater use of steroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide. The ten-year survival for both groups was high, with slightly higher rates among the younger at diagnosis group of SLE patients and a HR of 4.96 (95% CI 1.75–14.08), for risk of death in older at diagnosis compared to younger at diagnosis patients. Predictors of ten-year survival included increasing age at diagnosis (per year of age), male sex and Black race. Nephritis did not predict ten-year survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Iversen, Nicholas Nassikas, Tabatha Norton, Uzoma Oranu and Peter Tsao for their hard work in collecting and updating data, organizing and cleaning our databases. This study was supported in part by NIAMS T32AR007530 and P60AR057782.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors listed have financial disclosures relevant to this manuscript. None of the authors report any other, or relevant conflicts of interest related to this publication.

References

- 1.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Tom BD, Ibanez D, Farewell VT. Changing patterns in mortality and disease outcomes for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(11):2152–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080214. Epub 2008/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Abu-Shakra M, Farewell VT. Mortality studies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Results from a single center. III. Improved survival over 24 years. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(6):1061–5. Epub 1997/06/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Shakra M, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Gough J. Mortality studies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Results from a single center. I. Causes of death. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(7):1259–64. Epub 1995/07/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Shakra M, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Gough J. Mortality studies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Results from a single center. II. Predictor variables for mortality. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(7):1265–70. Epub 1995/07/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samanta A, Feehally J, Roy S, Nichol FE, Sheldon PJ, Walls J. High prevalence of systemic disease and mortality in Asian subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(7):490–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.7.490. Epub 1991/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bastian HM, Fessler BJ, Baethge BA, Friedman AW, et al. SLE in three ethnic groups XIII. the ‘weighted’ criteria as predictors of damage. Lupus. 2002;11(5):329–31. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu212xx. Epub 2002/07/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Petri M, Reveille JD, Ramsey-Goldman R, Kimberly RP. Baseline characteristics of a multiethnic lupus cohort: PROFILE. Lupus. 2002;11(2):95–101. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu155oa. Epub 2002/04/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastian HM, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Jr, Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Fessler BJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11(3):152–60. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu158oa. Epub 2002/05/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward MM, Studenski S. Clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Identification of racial and socioeconomic influences. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(4):849–53. Epub 1990/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petri M, Purvey S, Fang H, Magder LS. Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):4021–8. doi: 10.1002/art.34672. Epub 2012/08/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amador-Patarroyo MJ, Rodriguez-Rodriguez A, Montoya-Ortiz G. How does age at onset influence the outcome of autoimmune diseases? Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:251730. doi: 10.1155/2012/251730. Epub 2011/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernandez M, Vila LM, McGwin G, Apte M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII) Lupus. 2008;17(4):314–22. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875. Epub 2008/04/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hersh AO, von Scheven E, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Julian L, et al. Differences in long-term disease activity and treatment of adult patients with childhood- and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/art.24091. Epub 2009/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72(2):113–24. Epub 1993/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso MD, Martinez-Vazquez F, de Teran TD, Miranda-Filloy JA, Dierssen T, Blanco R, et al. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Northwestern Spain: differences with early-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and literature review. Lupus. 2012;21(10):1135–48. doi: 10.1177/0961203312450087. Epub 2012/06/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan TC, Fang H, Magder LS, Petri MA. Differences between male and female systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic population. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(4):759–69. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111061. Epub 2012/03/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. Epub 1997/10/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller RG. Simultaneous statistical inference. Springer Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin H, Wei JC, Tan CY, Liu YY, Li YH, Li FX, et al. Survival analysis of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a cohort study in China. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(12):1683–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2073-6. Epub 2012/09/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomic-Lucic A, Petrovic R, Radak-Perovic M, Milovanovic D, Milovanovic J, Zivanovic S, et al. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features, course, and prognosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2238-y. Epub 2013/03/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renau AI, Isenberg DA. Male versus female lupus: a comparison of ethnicity, clinical features, serology and outcome over a 30 year period. Lupus. 2012;21(10):1041–8. doi: 10.1177/0961203312444771. Epub 2012/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Danila MI, Zhang J, Bastian HM, et al. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on renal damage in patients with lupus nephritis: LXV, data from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(6):830–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24538. Epub 2009/05/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urowitz MB, Bookman AA, Koehler BE, Gordon DA, Smythe HA, Ogryzlo MA. The bimodal mortality pattern of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 1976;60(2):221–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90431-9. Epub 1976/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bastian HM, Roseman J, Lisse J, Fessler BJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VII [correction of VIII]. Predictors of early mortality in the LUMINA cohort. LUMINA Study Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(2):191–202. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<191::AID-ANR173>3.0.CO;2-2. Epub 2001/04/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borchers AT, Keen CL, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Surviving the butterfly and the wolf: mortality trends in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3(6):423–53. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.04.002. Epub 2004/09/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]