In this study, the crystal structure of a DsbE or DsbF homologue protein from Corynebacterium diphtheriae has been determined, which revealed a thioredoxin-like domain with a typical CXXC active site.

Keywords: Dsb family, disulfide isomerase, Gram-positive bacteria

Abstract

Disulfide-bond formation, mediated by the Dsb family of proteins, is important in the correct folding of secreted or extracellular proteins in bacteria. In Gram-negative bacteria, disulfide bonds are introduced into the folding proteins in the periplasm by DsbA. DsbE from Escherichia coli has been implicated in the reduction of disulfide bonds in the maturation of cytochrome c. The Gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes DsbE and its homologue DsbF, the structures of which have been determined. However, the two mycobacterial proteins are able to oxidatively fold a protein in vitro, unlike DsbE from E. coli. In this study, the crystal structure of a DsbE or DsbF homologue protein from Corynebacterium diphtheriae has been determined, which revealed a thioredoxin-like domain with a typical CXXC active site. Structural comparison with M. tuberculosis DsbF would help in understanding the function of the C. diphtheriae protein.

1. Introduction

The Dsb (disulfide bond) family of proteins is involved in the formation, rearrangement and cleavage of the disulfide bonds of proteins (Ireland et al., 2014 ▶; Yu & Kroll, 1999 ▶; Zhang & Donnenberg, 1996 ▶). They contain a conserved thioredoxin-like domain and share a common sequence motif (CXXC) at their active sites (Martin, 1995 ▶). These proteins are associated with virulence in many pathogens and promote the folding of a wide range of virulence proteins, such as toxins, adhesins, flagella and so forth (Heras et al., 2009 ▶; Shouldice et al., 2011 ▶; Denoncin & Collet, 2013 ▶). Thus, they have been considered as attractive molecular targets for the development of new antibiotics (Premkumar & Chaube, 2013 ▶).

The Dsb proteins have been best characterized in Escherichia coli. E. coli DsbA is a monomeric protein that catalyzes the oxidation of reduced, unfolded proteins with a reactive disulfide bond in the active-site CXXC motif (Hatahet et al., 2014 ▶). Although these proteins share the CXXC motif, they have different chemical properties such as the redox potential and pK a value. Some Dsb proteins act as reductants, while others act as oxidants. The oxidized state of DsbA is maintained in vivo by the transmembrane protein DsbB, which is in turn oxidized by ubiquinone in the electron-transport system (Hatahet et al., 2014 ▶). DsbC is a homodimeric thioredoxin-like protein and is involved in the reduction/isomerization of incorrect disulfide bonds in certain periplasmic proteins (Chen et al., 1999 ▶; McCarthy et al., 2000 ▶; Cho & Collet, 2013 ▶; Denoncin & Collet, 2013 ▶). DsbE is another well characterized Dsb protein in E. coli. DsbE is a monomeric thioredoxin-like protein that is involved in cytochrome c maturation by the reduction of thiol ether linkers to apocytochrome c (Grovc et al., 1996 ▶). DsbC and DsbE act as reductants, and the transmembrane protein DsbD maintains the proteins in the reduced state (Stewart et al., 1999 ▶; Gruber et al., 2006 ▶).

Gram-positive bacteria do not have a conventional periplasm because of the lack of the outer membrane. DsbA and DsbE homologue proteins have been found in Gram-positive bacteria, but DsbC homologues have not been identified to date. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), Mtb DsbA (Rv2969c), Mtb DsbE (Rv2878c, also known as MPT53) and its homologue Mtb DsbF (Rv1677) have been identified together with Mtb DsbD (Rv2874), which is a potential partner protein of DsbE and DsbF (Goulding et al., 2004 ▶; Chim et al., 2010 ▶; Ramamurthy et al., 2013 ▶; Wang et al., 2013 ▶). Crystal structures and biochemical studies of Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF revealed a conserved thioredoxin fold in the proteins exhibiting a disulfide-bond-introducing activity, which is rather similar to the function of E. coli DsbA (Goulding et al., 2004 ▶; Chim et al., 2010 ▶). The Mtb DsbF redox potential is more oxidizing and its reduced state is more stable than that of Mtb DsbE (Chim et al., 2010 ▶). Moreover, the expression pattern of Mtb DsbF is anticorrelated with Mtb DsbE (Goulding et al., 2004 ▶; Chim et al., 2010 ▶). These findings suggested that Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF may function under different conditions (Chim et al., 2010 ▶).

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is a Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria (Zakikhany & Efstratiou, 2012 ▶). Genomic analysis of C. diphtheriae suggested that the bacterium has putative DsbA and DsbF (or DsbE) genes. The DsbF homologue protein was predicted to be transported into the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane via a putative N-terminal signal sequence. In this study, we have determined the crystal structure of the DsbF homologue from C. diphtheriae (CdDsbF) at 2.1 Å resolution.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Construction of the expression vector for CdDsbF

A DNA fragment encoding a truncated form of CdDsbF (NP_938792.1) consisting of residues 29–185 was amplified by PCR using the genomic DNA of C. diphtheriae as a template with the 5′-primer GGTTCAGCAGGTCAGGATGCGGTTG and the 3′-primer TCATGAGAGAGAATCAATAACCTTGAT. The resulting DNA fragment was inserted into the NcoI and XhoI sites of the vector pProEX-HTA (Invitrogen) to add a hexahistidine tag at the N-terminus of the protein. The presence of the correct gene was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

2.2. Overexpression and purification of the CdDsbF protein

CdDsbF was expressed using E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) cells and purified. The cells were grown aerobically at 310 K in LB medium containing 50 µg ml− 1 ampicillin. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactoside at an A 600 of ∼1.0 and the cells were harvested 5 h after induction. The cells were harvested using high-speed centrifugation and were resuspended in 20 mM Tris buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After disruption by sonication, the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 19 000g for 0.5 h. The protein was initially purified by Ni–NTA affinity chromatography. The hexahistidine tag was then removed from the protein by overnight treatment with TEV protease in the presence of 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The CdDsbF protein was applied onto a HiLoad Superdex 16/60 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 8.0 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The purified protein was concentrated to 23 mg ml− 1 using a Centriprep (Millipore, USA) and stored frozen at 190 K until use. The protein concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm based on the molar extinction coefficient (20 065 M −1 cm−1).

2.3. Crystallization and data collection

Initial crystallization of CdDsbF was performed with commercially available screening solutions (Hampton Research, USA). Rod-shaped crystals were obtained by the vapour-diffusion technique at 287 K in sitting drops. Equal volumes (about 1 µl) of 10 mg ml−1 protein solution and reservoir solution consisting of 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 30% PEG 4K were mixed. For cryoprotection, the crystals were briefly soaked in reservoir solution supplemented with 20% MPD. X-ray diffraction data from the crystals were collected using an ADSC Q-315 detector on beamline 5C of Pohang Light Source (PLS), Republic of Korea at 100 K. The diffraction data sets were processed and scaled to 2.1 Å resolution with the HKL-2000 package (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The crystal belonged to space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 78.0, b = 36.1, c = 62.5 Å, β = 112°.

2.4. Structural determination and refinement

Initial phases were determined by the molecular-replacement program MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▶) from the CCP4 package (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) using the coordinates of a secreted thiol-disulfide isomerase from Corynebacterium glutamicum (PDB entry 3lwa; Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, unpublished work) as a search model. Model building was performed using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▶) and refinement was carried out by PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▶). Crystallographic data statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶. A random set of 5% of the reflections was excluded from the refinement for cross-validation of the refinement strategy. Water molecules were assigned automatically for peaks >2σ in the F o − F c difference maps by cycles of refinement using PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▶) and some of them were deleted by manual inspection. The quality of the model was checked using MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010 ▶). All residues were in the favoured region in the Ramachandran plot. The detailed statistics for the X-ray data collection and refinement are presented in Table 1 ▶. The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB entry 4pq1). Fgures were generated using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

Table 1. X-ray data-collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Source | 5C, PLS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97951 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 36.18–2.10 (2.17–2.10) |

| Space group | P21 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 78.0, b = 36.1, c = 62.5, β = 112 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 250 |

| No. of unique reflections | 37665 |

| Multiplicity | 3.6 (2.3) |

| R merge (%) | 9.9 (22.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.4 (86.1) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 18.31 (5.02) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 36–2.10 (2.17–2.10) |

| R factor (%) | 18.3 (28.8) |

| R free † (%) | 24.9 (34.9) |

| Average B value (Å2) | 34.0 |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 25.65 |

| R.m.s.d. for bonds (Å) | 0.008 |

| R.m.s.d. for angles (°) | 1.088 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favoured (%) | 96.82 |

| Additionally favoured (%) | 2.87 |

| Coordinate error‡ (Å) | 0.27 |

| PDB code | 4pq1 |

R free was calculated with 5% of the data set.

Maximum-likelihood estimate

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Putative DsbF-like protein of C. diphtheriae

The complete sequence of the C. diphtheriae genome has been identified (Mokrousov, 2009 ▶). To find genes that might be involved in the disulfide-formation/cleavage system in the extracellular region of C. diphtheriae, we carried out a BLAST search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.mih.gov/BLAST) and identified two genes that contain both a thioredoxin-like domain and a putative signal sequence: NP_938792.1 (annotated as an electron-transport-like protein) and YP_005126824 (annotated as a putative secreted protein). In this study, we focused on NP_938792.1 and further sequence analyses revealed that the gene shows a high sequence similarity to Mtb DsbE and DsbF. Thus, we refer to NP_938792.1 as CdDsbF in this study.

3.2. Structural determination

CdDsbF is a protein of 186 amino-acid residues with a putative N-terminal signal peptide (residues 1–26) as predicted by SignalP (Petersen et al., 2011 ▶) with high significance. The mature form of CdDsbF without the putative signal peptide was successfully crystallized using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The crystal structure of CdDsbF was determined by the molecular-replacement method using the coordinates of a secreted thiol-disulfide isomerase from C. glutamicum (PDB entry 3lwa) as a search model. The crystals of CdDsbF belonged to space group P21 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit (Table 1 ▶). The final model, refined against the 2.1 Å resolution data, contained residues 29–185. The structure was refined to a free R value of 24.9% with good stereochemistry.

3.3. Overall structure

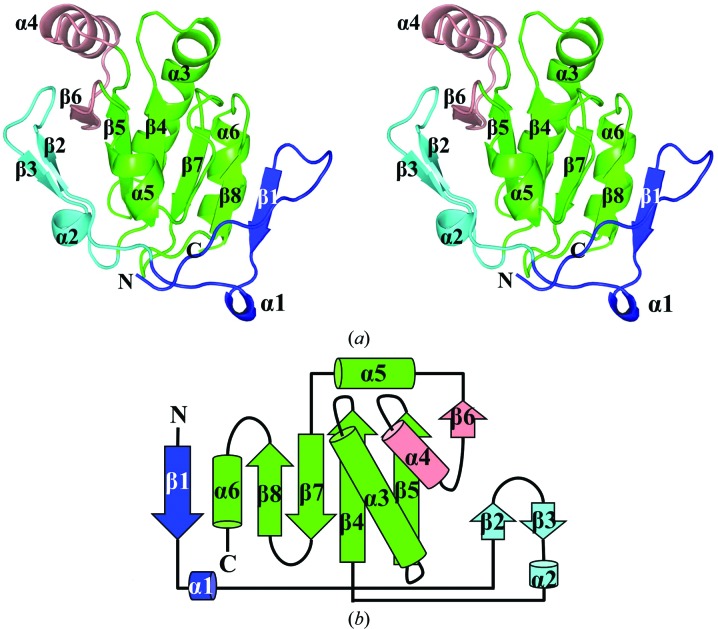

CdDsbF shows an overall single-domain structure consisting of a core region and an additional N-terminal region. The core region contains a thioredoxin-fold region and a protruding α–β region. The thioredoxin-like domain forms the core of CdDsbF and contains a four-stranded β-sheet (β4, β5, β7 and β8) and three flanking α-helices (α3, α5 and α6) (Fig. 1 ▶). Of the α-helices, α3 is long and highly curved, making a key β4–α3–β5 motif in the thioredoxin-like domain region. The protruding α–β region (α4 and β6) is inserted between β5 and α5 in the thioredoxin-like domain. The additional N-terminal region is linked to the N-terminus of the thioredoxin-like domain, which can be divided into two parts. A short 310-helix (α1) and a β-strand (β1) are in close proximity to β8 of the core region, forming a sixth β-strand in the central β-sheet in the thioredoxin-like domain. The paired β-strands and a short α-helix (β2–β3–α2) are located on the opposite face of the core region.

Figure 1.

Structure of CdDsbF. (a) Ribbon representation of CdDsbF. CdDsbF shows an overall single-domain structure consisting of a thioredoxin-fold domain and additional motifs. The thioredoxin-fold domain forms the core region of CdDsbF containing a four-stranded β-sheet (β4, β5, β7 and β8) and three flanking α-helices (α3, α5 and α6) (green). A protruding region containing α4 and β6 is located between β5 and α5 in the thioredoxin-fold domain (salmon). (b) Schematic drawing of the folding topology of CdDsbF. The colour profile and the secondary-structural element numbering are the same as in (a).

3.4. Structural features of the CdDsbF active site

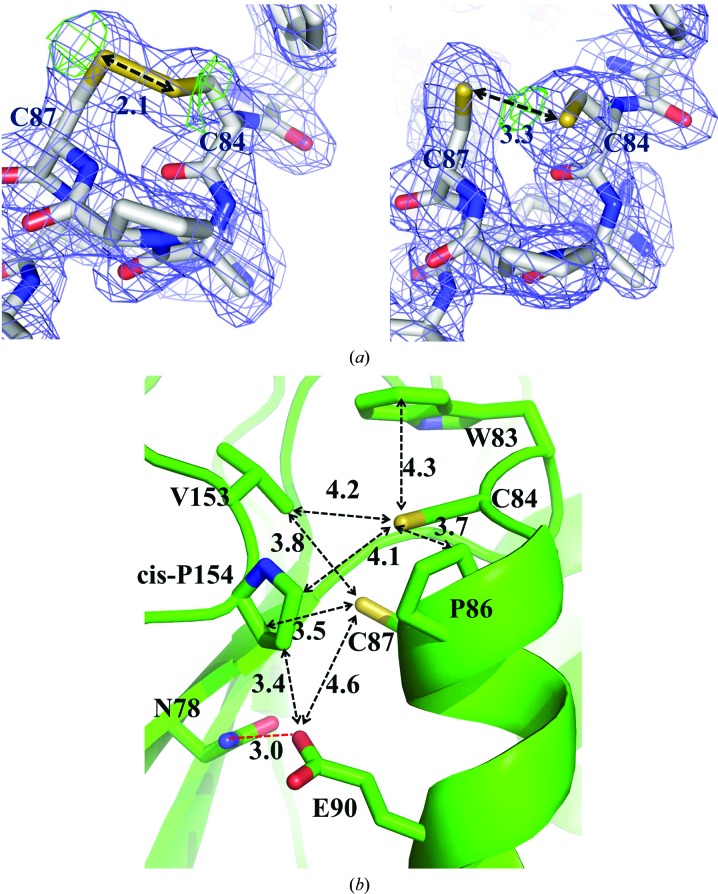

The two cysteine residues (Cys84 and Cys87) in the active-site CXXC motif adopt a right-handed hook conformation as observed in many thioredoxin-fold proteins (Atkinson & Babbitt, 2009 ▶). The electron density for the two cysteines indicated that the reduced and oxidized forms of the cysteine residues coexist with occupancies of approximately 50% (Fig. 2 ▶ a). The F o − F c density could not be removed in either state. The distances between the Sγ atoms of the cysteine residues were measured as 2.1 and 3.3 Å for the oxidized and reduced forms in the electron-density map, respectively, which are consistent with the expected distances of the reduced and oxidized forms of the CXXC motif (Crow et al., 2009 ▶).

Figure 2.

Structural features of the CdDsbF active site. (a) Electron density surrounding the active-site CXXC motif of CdDsbF where the cysteines are modelled in both the (left) oxidized and (right) reduced forms. The 2F o − F c electron-density mesh (blue) and the F o − F c negative density mesh (green) are contoured at 1.0σ and 3.0σ, respectively. Shown are stick cartoons of the active site, in which the C, O, N and S atoms are coloured white, red, blue and yellow, respectively. (b) Close-up view of the CdDsbF active site showing the CAPC motif, the residues adjacent to the catalytic motif and a hydrogen-bond interaction (red dashed line) stabilizing the reduced form.

As in other thioredoxin-fold proteins, the Sγ atom of Cys84 is exposed on the surface, while the Sγ atom of Cys87 is buried. The two thiol groups or the disulfide of the CXXC motif do not make an apparent polar interaction in the structure (Fig. 2 ▶ b). In the conformation of the reduced form of CdDsbF, the Sγ atoms of Cys84 and Cys87 show distances of 4.1 and 3.5 Å, respectively, to cis-Pro154, which is conserved in all known thioredoxin superfamily proteins (Fig. 2 ▶ b and black arrow in Fig. 3 ▶ a). Additionally, the Sγ atom of the exposed Cys84 residue forms hydrophobic interactions with Trp83, Pro86 and Val153 (4.3, 3.7 and 4.2 Å, respectively; Fig. 2 ▶ b).

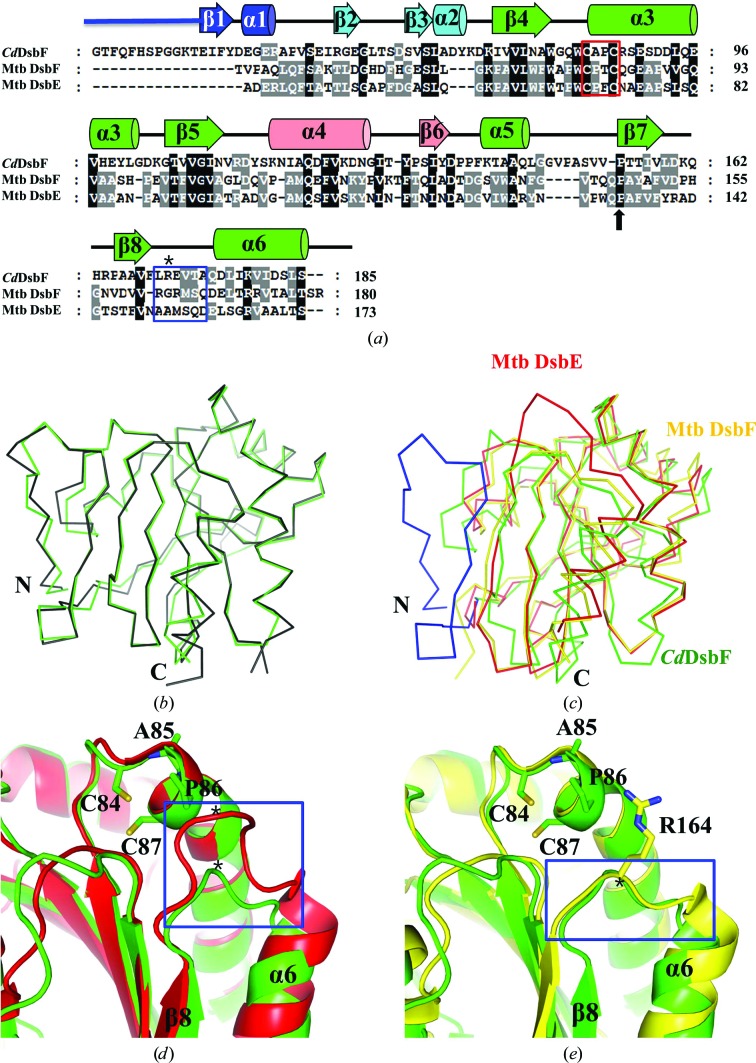

Figure 3.

Sequence and structural comparison with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF. (a) Amino-acid sequence alignment of CdDsbF with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF performed by ClustalX and modified manually based on the structure-based alignment. Secondary-structure elements are shown based on the structure of CdDsbF. The CXXC motif and cis-Pro are indicated by a red box and a black arrow, respectively. The β8–α6 loop indicated by a blue box and the residues marked with asterisks are mentioned in the main text and in (d) and (e). (b) Superimposition of the structures of CdDsbF (green) and C. glutamicum thioredoxin-like protein (PDB entry 3lwa; black). (c) Superimposition of the structures of CdDsbF (green), Mtb DsbE (red) and Mtb DsbF (yellow). CdDsbF has a longer N-terminal region (blue) compared with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF. (d) Structure superimposition of a loop region of CdDsbF (green) and Mtb DsbE (red). The loop region (blue box) connecting β8 to α6 is closer to the CXXC motif in Mtb DsbE than in CdDsbF in the three-dimensional structures. (e) Structure superimposition of a loop region of CdDsbF (green) and Mtb DsbF (yellow). The loop region (blue box) connecting β8 to α6 is at a similar distance to the CXXC motif in the three-dimensional structures.

3.5. Sequence and structural comparisons of CdDsbF with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF

To find proteins with a similar fold, we used the CdDsbF structure in a search with the DALI server (Holm & Rosenström, 2010 ▶). A thioredoxin-fold protein from C. glutamicum, which was annotated as a secreted thiol-disulfide isomerase, was found to be the top solution (PDB entry 3lwa; Cα r.m.s.d. of 0.346 Å and Z-score of 28.9 between 167 residues). The structural superposition revealed that the two proteins share a structure as well as an overall fold (Fig. 3 ▶ b), indicating that CdDsbF might be functionally related to the putative secreted thiol-disulfide isomerase. However, the function of the protein needs to be investigated since no report regarding the structure and function of this protein has been published.

To gain an insight into the function of CdDsbF, we compared CdDsbF with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF because they have a similar fold to CdDsbF and their functions have been investigated. CdDsbF shows 23.1 and 23.3% sequence identity to Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF, respectively (Fig. 3 ▶ a). Interestingly, CdDsbF has a longer N-terminal region consisting of a 12-amino-acid loop and a β-strand and a short α-helix, which is unique to CdDsbF compared with Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF (Fig. 3 ▶; coloured blue). The β-strand and α-helical region in the N-terminal extended region might be involved in the structural integrity of the protein and the N-terminal 12 residues showing a loop conformation might provide a longer tethering from the anchor to the plasma membrane.

The core residues (residues 41–185) of the CdDsbF structure were superposed on Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF (Fig. 3 ▶ c; red and yellow, respectively). The r.m.s.d. values suggested that CdDsbF more closely resembles Mtb DsbE (Cα r.m.s.d. = 1.047 Å) than Mtb DsbF (Cα r.m.s.d. 1.334 Å). However, a notable difference was observed in a loop region connecting β8 to α6 (the β8–α6 loop; Fig. 3 ▶ a; blue box), which is in close proximity to the CXXC motif in the three-dimensional structure (Figs. 3 ▶ d and 3 ▶ e). The corresponding region of Mtb DsbF exhibited a similar conformation (Fig. 3 ▶ e) but the β8–α6 loop is extended in Mtb DsbE (Fig. 3 ▶ d).

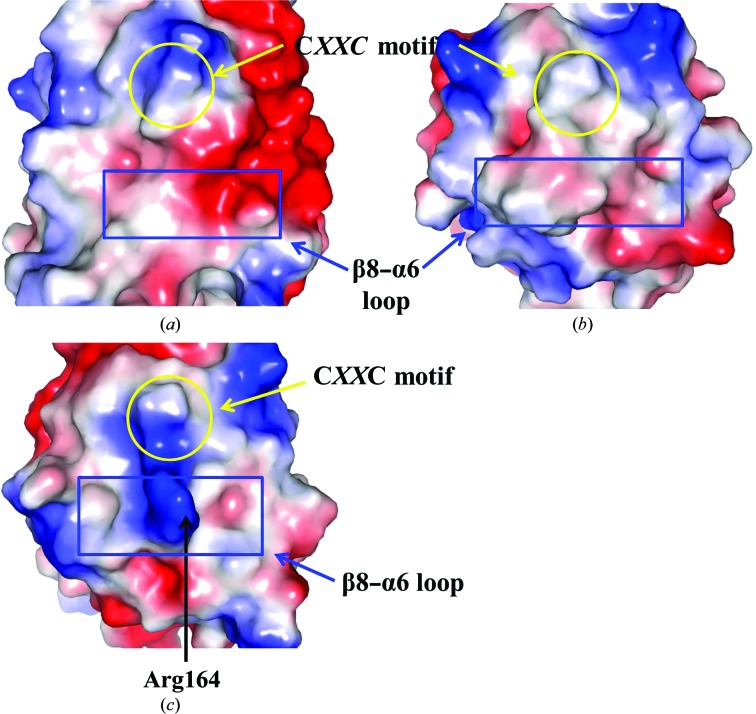

We next compared the electrostatic potential of the molecular surfaces of the proteins (Fig. 4 ▶). The most noticeable feature was found in the β8–α6 loop. The loop of CdDsbF is mostly negatively charged owing to the exposed Glu171, whereas the corresponding residues of Mtb DsbE and Mtb DsbF are replaced by methionine and arginine, respectively (Figs. 3 ▶ a, 3 ▶ d and 3 ▶ e; indicated by an asterisk). In particular, Arg164 in Mtb DsbF protrudes from the main body, exposing the positive charge on the surface (Fig. 4 ▶ c). Thus, our findings suggest that CdDsbF and Mtb DsbF might recognize a different spectrum of substrate proteins.

Figure 4.

Electrostatic potential of the molecular-surface representations of CdDsbF (a), Mtb DsbE (b) and Mtb DsbF (c). Positive and negative electrostatic potentials are displayed on the surface in blue and red, respectively. The CXXC motif (yellow circle) and the β8–α6 loop (blue box) are indicated.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we determined the crystal structure of a DsbF homologue from C. diphtheriae at 2.1 Å resolution. Structural comparisons with the DsbE and DsbF proteins from Mtb were performed, which would help to elucidate the function of the C. diphtheriae protein.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: DsbF homologue, 4pq1

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (Grant No. H12C0947) and by an NRF grant (2011-0028553) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. This study utilized beamline 5C at Pohang Accelerator Laboratory, Republic of Korea. The authors declare that there are no competing commercial interests related to this work.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Atkinson, H. J. & Babbitt, P. C. (2009). PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, J., Song, J.-L., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Cui, D.-F. & Wang, C.-C. (1999). J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19601–19605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, V. B., Arendall, W. B., Headd, J. J., Keedy, D. A., Immormino, R. M., Kapral, G. J., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chim, N., Riley, R., The, J., Im, S., Segelke, B., Lekin, T., Yu, M., Hung, L.-W., Terwilliger, T., Whitelegge, J. P. & Goulding, C. W. (2010). J. Mol. Biol. 396, 1211–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.-H. & Collet, J.-F. (2013). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1690–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crow, A., Lewin, A., Hecht, O., Carlsson Möller, M., Moore, G. R., Hederstedt, L. & Le Brun, N. E. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23719–23733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. (2002). PyMOL http://www.pymol.org.

- Denoncin, K. & Collet, J.-F. (2013). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goulding, C. W., Apostol, M. I., Gleiter, S., Parseghian, A., Bardwell, J., Gennaro, M. & Eisenberg, D. (2004). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3516–3524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grovc, J., Busby, S. & Cole, J. (1996). Mol. Gen. Genet. 252, 332–341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gruber, C. W., Cemazar, M., Heras, B., Martin, J. L. & Craik, D. J. (2006). Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hatahet, F., Boyd, D. & Beckwith, J. (2014). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1844, 1402–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heras, B., Shouldice, S. R., Totsika, M., Scanlon, M. J., Schembri, M. A. & Martin, J. L. (2009). Nature Rev. Microbiol. 7, 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holm, L. & Rosenström, P. (2010). Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ireland, P. M., McMahon, R. M., Marshall, L. E., Halili, M., Furlong, E., Tay, S., Martin, J. L. & Sarkar-Tyson, M. (2014). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 606–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martin, J. L. (1995). Structure, 3, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, A. A., Haebel, P. W., Törrönen, A., Rybin, V., Baker, E. N. & Metcalf, P. (2000). Nature Struct. Biol. 7, 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mokrousov, I. (2009). Infect. Genet. Evol. 9, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G. & Nielsen, H. (2011). Nature Methods, 8, 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Premkumar, K. V. & Chaube, S. K. (2013). J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 30, 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramamurthy, C., Sampath, K. S., Arunkumar, P., Kumar, M. S., Sujatha, V., Premkumar, K. & Thirunavukkarasu, C. (2013). Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 36, 1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shouldice, S. R., Heras, B., Walden, P. M., Totsika, M., Schembri, M. A. & Martin, J. L. (2011). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1729–1760. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stewart, E. J., Katzen, F. & Beckwith, J. (1999). EMBO J. 18, 5963–5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, L., Li, J., Wang, X., Liu, W., Zhang, X. C., Li, X. & Rao, Z. (2013). Protein Cell, 4, 628–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Yu, J. & Kroll, J. S. (1999). Microbes Infect. 1, 1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zakikhany, K. & Efstratiou, A. (2012). Future Microbiol. 7, 595–607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-Z. & Donnenberg, M. S. (1996). Mol. Microbiol. 21, 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: DsbF homologue, 4pq1