In the past decade, there has been progress in using the atomic force microscope (AFM) to probe the structural and physical properties of microbial surfaces, indicating that the instrument is taking root in the microbiological science community (15, 16). Yet, two important bottlenecks have hindered the widespread use of the technique by microbiologists: the lack of appropriate sample preparation procedures and the limited number of studies demonstrating what real benefits can be gained from this new tool. In this issue, Touhami and coworkers (30) report measurements that represent an important step in demonstrating the power of AFM in cellular microbiology. They combine AFM imaging in aqueous solution and thin-section transmission electron microscopy to investigate the changes in the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus cells as they grow and divide. A good correlation of the structural events of division is found using the two techniques, and the AFM is shown to provide new information. The major findings of this study are as follows. First, nanoscale perforations are seen around the septal annulus at the onset of division and found to merge with time to form a single larger perforation. These holes are suggested to reflect so-called murosomes, i.e., cell wall structures possessing high levels of autolytic activity and which digest peptidoglycan. This interpretation is supported by transmission electron microscopy, which reveals a midline of reactive material in the developing septum and provides evidence for peptidoglycan hydrolysis in septa. Second, after daughter cells have separated, concentric rings and a central depression are observed on the surface of the new cell wall. The ring patterns, consistent with previous electron microscopy observations, are suggested to reflect newly formed peptidoglycan. Third, the combination of AFM imaging and force-distance curves shows that the older wall is partitioned into smooth and gel-like zones with different properties that are attributed to cell wall turnover. Taken together, these results clearly show that the AFM is able to provide new information on bacterial surfaces by allowing structural changes to be revealed directly in growth medium.

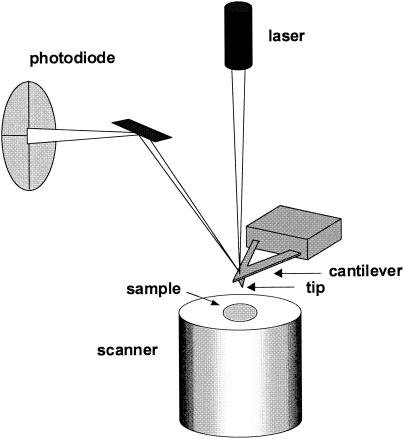

Touhami et al. take advantage of two unique features of the AFM: the ability to generate three-dimensional images of hydrated cell surfaces with nanometer resolution and the possibility to locally measure biomolecular interactions by means of force spectroscopy. AFM images are created by sensing the force between a sharp tip and the sample surface (Fig. 1). The sample is mounted on a piezoelectric scanner which ensures three-dimensional positioning with high accuracy. While the tip (or sample) is being scanned in the x,y directions, the force interacting between tip and specimen is monitored with piconewton sensitivity. This force is measured by the deflection of a soft cantilever which is detected by a laser beam focused on the free end of the cantilever and reflected into a photodiode. AFM cantilevers and tips are generally made of silicon or silicon nitride using microfabrication techniques. Besides being applied as a microscope, the AFM can also be used in the force spectroscopy mode to measure molecular interactions and physicochemical properties. Here, force-distance curves are recorded by monitoring at a given x,y location the cantilever deflection as a function of the vertical displacement of the piezoelectric scanner.

FIG. 1.

Basic elements of the AFM.

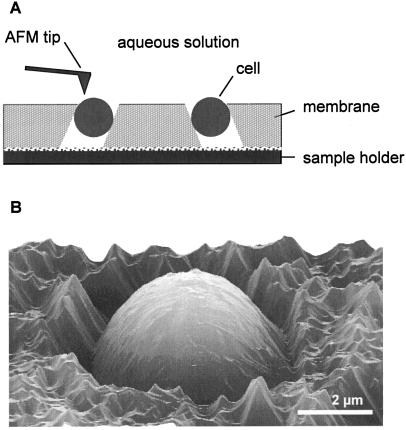

Sample preparation is a crucial step for successful biological AFM in that the sample must always be well attached to a solid support. For biomolecules, good results have been obtained using physical adsorption or chemical fixation onto flat supports such as mica (21). However, these approaches are not appropriate for large specimens such as bacteria because the cell-support contact area is very small, leading most of the time to cell detachment by the scanning tip. To solve this problem, Touhami et al. (30) trapped their cells mechanically in the pores of a polymer membrane (Fig. 2A). This approach permits the imaging of single bacterial, yeast, and fungal cells under aqueous conditions while minimizing denaturation of the specimen (13, 17) (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Imaging individual cells under physiological conditions. (A) In the porous-membrane method, a concentrated cell suspension is gently sucked through an isopore polycarbonate membrane with pore size slightly smaller than that of the cell. (B) Three-dimensional AFM height image showing a dormant spore of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae trapped in a pore.

The study by Touhami et al. (30) is an important contribution to the existing literature on the application of the AFM in microbiology. What novel information have we gained so far using this technique? In the mid-1990s, Sleytr's and Engel's groups pioneered the imaging of bacterial S-layers made of two-dimensional protein crystals with the AFM (25, 26). Since then, the exceptional signal-to-noise ratio of the instrument has enabled individual S-layer proteins to be imaged to a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1 nm and a vertical resolution of 0.1 to 0.2 nm and to monitor conformational changes in single molecules (23).

More recently, the AFM has enabled researchers to visualize the surface architecture of cells, including bacteria (9, 10, 12, 27, 33), yeasts (4), fungal spores (13, 32), diatoms (11), and viruses (20). Biofilms have also been visualized by AFM, providing data that is complementary to that obtained with conventional microscopy techniques (5, 6, 18). Because AFM works in aqueous solution, the exciting question of whether it is possible to observe dynamic processes in real-time arises. In this context, the enzyme digestion of yeast cell walls could be monitored (4) and the change of cell surface structure during germination of fungal spores could be tracked (13, 32). The Touhami et al. article (30) is the first such dynamic study performed on bacteria.

Physicochemical properties of microbial surfaces have traditionally been difficult to explore at the subcellular level because of the small size of microorganisms. Furthermore, direct information on molecular interactions was not available due to the lack of appropriate techniques. In the last years, these properties were studied using AFM force spectroscopy with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution. AFM force measurements have enabled direct, quantitative measurement of the elastic properties of isolated cell walls (34, 35) and whole cells (28). Relations were found between force-distance curve characteristics recorded on bacterial strains and macroscopic physicochemical properties (31) and cell adhesion behavior (2). Chemical functionalization of AFM tips has made it possible to map the local surface hydrophobicity and charges of individual cells (3, 14). The remarkable force sensitivity of the instrument has enabled researchers to manipulate single cell surface molecules and to measure their molecular interactions, providing new insights into the molecular bases of molecular elasticity (1, 32), protein folding (24), and protein-protein assembly (22). Interestingly, functionalizing the AFM tip with biomolecules and living cells has also enabled quantitative measurements of receptor-ligand interactions (7, 29) and cell-material interactions (8, 19).

The present brief survey, including the Touhami et al. contribution, indicates that rapid advances have occurred in applying AFM to microbiological specimens. AFM imaging and force spectroscopy promise to improve our understanding of the structure-function relationships of cell surfaces. As the technique becomes more routine, we can confidently approach previously inaccessible questions. For instance, it should soon be possible to monitor conformational changes at cell surfaces and to observe cell surface interaction with antibodies and drugs.

Acknowledgments

Y.F.D. is a Research Associate of the Belgian National Foundation for Scientific Research (FNRS).

The support of the FNRS, of the Federal Office for Scientific, Technical, and Cultural Affairs (Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Program), and of the Research Department of Communauté Française de Belgique (Concerted Research Action) is gratefully acknowledged.

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Lail, N. I., and T. A. Camesano. 2002. Elasticity of Pseudomonas putida KT2442 surface polymers probed with single-molecule force microscopy. Langmuir 18:4071-4081. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Lail, N. I., and T. A. Camesano. 2003. Role of lipopolysaccharides in the adhesion, retention, and transport of Escherichia coli JM109. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:2173-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahimou, F., F. A. Denis, A. Touhami, and Y. F. Dufrêne. 2002. Probing microbial cell surface charges by atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 18:9937-9941. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahimou, F., A. Touhami, and Y. F. Dufrêne. 2003. Real-time imaging of the surface topography of living yeast cells by atomic force microscopy. Yeast 20:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auerbach, I. D., C. Sorensen, H. G. Hansma, and P. A. Holden. 2000. Physical morphology and surface properties of unsaturated Pseudomonas putida biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 182:3809-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beech, I. B., J. R. Smith, A. A. Steele, I. Penegar, and S. A. Campbell. 2002. The use of atomic force microscopy for studying interactions of bacterial biofilms with surfaces. Coll. Surf. B Biointerfaces 23:231-247. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benoit, M., D. Gabriel, G. Gerisch, and H. E. Gaub. 2000. Discrete interactions in cell adhesion measured by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen, W. R., R. W. Lovitt, and C. J. Wright. 2001. Atomic force microscopy study of the adhesion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Coll. Interf. Sci. 237:54-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camesano, T. A., M. J. Natan, and B. E. Logan. 2000. Observation of changes in bacterial cell morphology using tapping mode atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 16:4563-4572. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chada, V. G. R., E. A. Sanstad, R. Wang, and A. Driks. 2003. Morphogenesis of Bacillus spore surfaces. J. Bacteriol. 185:6255-6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford, S. A., M. J. Higgins, P. Mulvaney, and R. Wetherbee. 2001. Nanostructure of the diatom frustule as revealed by atomic force and scanning electron microscopy. J. Phycol. 37:543-554. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doktycz, M. J., C. J. Sullivan, P. R. Hoyt, D. A. Pelletier, S. Wu, and D. P. Allison. 2003. AFM imaging of bacteria in liquid media immobilized on gelatin coated mica surfaces. Ultramicroscopy 97:209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dufrêne, Y. F., C. J. P. Boonaert, P. A. Gerin, M. Asther, and P. G. Rouxhet. 1999. Direct probing of the surface ultrastructure and molecular interactions of dormant and germinating spores of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Bacteriol. 181:5350-5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufrêne, Y. F. 2000. Direct characterization of the physicochemical properties of fungal spores using functionalized AFM probes. Biophys. J. 78:3286-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dufrêne, Y. F. 2002. Atomic force microscopy, a powerful tool in microbiology. J. Bacteriol. 184:5205-5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufrêne, Y. F. 2003. Recent progress in the application of atomic force microscopy imaging and force spectroscopy to microbiology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasas, S., and A. Ikai. 1995. A method for anchoring round shaped cells for atomic force microscope imaging. Biophys. J. 68:1678-1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolari, M., U. Schmidt, E. Kuismanen, and M. S. Salkinoja-Salonen. 2002. Firm but slippery attachment of Deinococcus geothermalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:2473-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lower, S. K., M. F. Hochella, and T. J. Beveridge. 2001. Bacterial recognition of mineral surfaces: nanoscale interactions between Shewanella and α-FeOOH. Science 292:1360-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malkin, A. J., A. McPherson, and P. D. Gershon. 2003. Structure of intracellular mature vaccinia virus visualized by in situ atomic force microscopy. J. Virol. 77:6332-6340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller, D. J., M. Amrein, and A. Engel. 1997. Adsorption of biological molecules to a solid support for scanning probe microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 119:172-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller, D. J., W. Baumeister, and A. Engel. 1999. Controlled unzipping of a bacterial surface layer with atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13170-13174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller, D. J., and A. Engel. 2002. Conformations, flexibility, and interactions observed on individual membrane proteins by atomic force microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 68:257-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oesterhelt, F., D. Oesterhelt, M. Pfeiffer, A. Engel, H. E. Gaub, and D. J. Müller. 2000. Unfolding pathways of individual bacteriorhodopsin. Science 288:143-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pum, D., and U. B. Sleytr. 1995. Monomolecular reassembly of a crystalline bacterial cell surface layer (S-layer) on untreated and modified silicon surfaces. Supramol. Sci. 2:193-197. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schabert, F. A., C. Henn, and A. Engel. 1995. Native Escherichia coli OmpF porin surfaces probed by atomic force microscopy. Science 268:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaer-Zammaretti, P., and J. Ubbink. 2003. Imaging of lactic acid bacteria with AFM: elasticity and adhesion maps and their relationship to biological and structural data. Ultramicroscopy 97:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Touhami, A., B. Nysten, and Y. F. Dufrêne. 2003. Nanoscale mapping of the elasticity of microbial cells by atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 19:4539-4543. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Touhami, A., B. Hoffmann, A. Vasella, F. A. Denis, and Y. F. Dufrêne. 2003. Aggregation of yeast cells: direct measurement of discrete lectin-carbohydrate interactions. Microbiology 149:2873-2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Touhami, A., M. H. Jericho, and T. J. Beveridge. 2004. Atomic force microscopy of cell growth and division in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:3286-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vadillo-Rodriguez, V., H. J. Busscher, W. Norde, J. de Vries, and H. C. van der Mei. 2003. On relations between microscopic and macroscopic physicochemical properties of bacterial cell surfaces: an AFM study on Streptococcus mitis strains. Langmuir 19:2372-2377. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Aa, B. C., R. M. Michel, M. Asther, M. T. Zamora, P. G. Rouxhet, and Y. F. Dufrêne. 2001. Stretching cell surface macromolecules by atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 17:3116-3119. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velegol, S. B., S. Pardi, X. Li, D. Velegol, and B. E. Logan. 2003. AFM imaging artifacts due to bacterial cell height and AFM tip geometry. Langmuir 19:851-857. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, W., P. J. Mulhern, B. L. Blackford, M. H. Jericho, M. Firtel, and T. J. Beveridge. 1996. Modeling and measuring the elastic properties of an archaeal surface, the sheath of Methanospirillum hungatei, and the implication for methane production. J. Bacteriol. 178:3106-3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao, X., M. Jericho, D. Pink, and T. Beveridge. 1999. Thickness and elasticity of gram-negative murein sacculi measured by atomic force microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 181:6865-6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]