Abstract

The emergence of high efficacy synthetic cannabinoids as drugs of abuse in readily available K2/”Spice” smoking blends has exposed users to much more potent and effective substances than the phytocannabinoids present in cannabis. Increasing reports of adverse reactions, including dependence and withdrawal, are appearing in the clinical literature. Here we investigated whether the effects of one such synthetic cannabinoid, 1-pentyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole (JWH-018), would be altered by a prior history of Δ9-THC exposure, in assays of conditioned taste aversion (CTA) and conditioned place preference (CPP.) In the CTA procedure, JWH-018 induced dramatic and persistent aversive effects in mice with no previous cannabinoid history, but the magnitude and duration of these aversive effects were significantly blunted in mice previously treated with an ascending dose regimen of Δ9-THC. Similarly, in the CPP procedure, JWH-018 also induced dose-dependent aversive effects in mice with no previous drug history, but mice exposed to Δ9-THC prior to place conditioning exhibited reduced aversions at the high JWH-018 dose, and apparent rewarding effects at the low dose of JWH-018. These findings suggest that a history of Δ9-THC exposure “protects” against aversive effects and “unmasks” appetitive effects of the high efficacy synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 in mice. This pattern of results implies that cannabinoid-naïve individuals administering K2/”Spice” products for the first-time may be at increased risk for adverse reactions, while those with a history of marijuana use may be particularly sensitive to the reinforcing effects of high efficacy cannabinoids present in these commercial smoking blends.

Keywords: cannabinoid, conditioned place preference, conditioned taste aversion, abuse liability, mouse

Introduction

Smoking blends containing high efficacy synthetic cannabinoids (often marketed as “K2” and “Spice”) have recently emerged as popular substitutes for cannabis. Commercial preparations of these products are readily available, heavily marketed toward young people, perceived as safe, and not easily detected in drug screens (Vardakou et al., 2010). Like Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the primary psychoactive constituent of marijuana, the synthetic compounds in these smoking products are presumed to elicit their psychoactive effects by activating CB1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1Rs) in the CNS, although many of these compounds possess much higher efficacy than Δ9-THC (Atwood et al., 2010; Brents et al., 2011). Importantly, the majority of young people using synthetic cannabinoids also abuse marijuana (Hu et al., 2011; Vandrey et al., 2012).

Preclinical data suggest that a history of Δ9-THC exposure alters the motivational properties of subsequent Δ9-THC. For example, Δ9-THC tends to elicit conditioned place aversion (CPA) in drug-naïve subjects, but will induce conditioned place preference (CPP) if subjects are first “primed” with pre-exposure to the drug (Tzschentke, 2007; Valjent and Maldonado, 2000). Similarly, a history of Δ9-THC blunts conditioned taste aversion (CTA) to a novel flavor paired with subsequent Δ9-THC administration (Fischer and Vail, 1980; Switzman et al., 1981). These findings suggest that the motivational effects of emerging high efficacy synthetic cannabinoids in those with a history of Δ9-THC use may dramatically differ from those observed in Δ9-THC-naïve users.

In these studies, we assessed aversive effects (using a CTA procedure) and appetitive effects (using CPP) of the high-efficacy aminoalkylindole synthetic cannabinoid 1-pentyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole (JWH-018) in mice, and determined how these effects were modulated by prior exposure to Δ9-THC. The major hypothesis tested in these studies was that prior exposure to Δ9-THC may render mice less sensitive to the aversive effects of JWH-018, but more sensitive to the appetitive / “rewarding” effects of this compound.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult (8 week old) male NIH Swiss mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were received at 20-23 g and housed 3 animals per Plexiglas cage (15.24×25.40×12.70 cm) in a temperature-controlled room maintained on a 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 07.00h.) Animals were fed Lab Diet rodent chow (Laboratory Rodent Diet #5001, PMI Feeds, Inc., St. Louis, MO) as needed to maintain weights within 28-30 g during experiments, and water was freely available in home cages. All studies were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health. Groups of 6 mice per condition were used in CTA and CPP experiments, and each subject was exposed to only one experimental treatment.

Δ9-THC pre-exposure

An escalating-dose regimen of Δ9-THC was used to establish a cannabinoid history in some subjects prior to behavioral testing, while control subjects were administered a similar repeated regimen of drug vehicle (see below). Injections were administered i.p. in the colony room, and escalated through 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 mg/kg Δ9-THC. This dose regimen was previously used to elicit tolerance to rate-decreasing effects in mice (unpublished observations.) Drug (or vehicle) was injected every other day, and saline was administered on intervening days, for 5 total drug (or vehicle) injections. The first pairing for CTA studies or the CPP initial preference session occurred 2 days after the final Δ9-THC (or vehicle) injection.

Conditioned taste aversion

Experiments were conducted in operant chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) enclosed within light- and sound-attenuating boxes. Two lighted nose-poke apertures were located on the front panel of the chamber with a reinforcement aperture centered between them. Head entries into either nose-poke aperture broke a photobeam and registered a response. Reinforced responses allowed mice a 5-s access period to a 0.01 ml dipper of evaporated milk (Kroger, Cincinnati, OH) diluted 50% with water, immediately followed by a 10-s timeout. Training sessions ended after either 60 minutes or after 60 milk presentations, whichever occurred first. Initial training sessions used a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement (FR1), and every 20th reinforcer earned incremented the FR by 1. Mice were shaped to a terminal FR5 across sessions, and CTA trials began when response rates varied no more than 20% for 3 consecutive training sessions. During CTA trials, a novel flavored solution was used to reinforce responding, consisting of 1 ml strawberry syrup (Kroger, Cincinnati, OH) per 8 ml of the milk reinforcer. Immediately after the first and second sessions where the flavored milk was available, mice were removed from the chamber, injected (IP) with 3.0 mg/kg JWH-018 (a dose which elicits dramatic unconditioned effects in the cannabinoid tetrad [Brents et al., 2011; 2013]), then returned to the home cage in the colony room. Thus, the flavored milk reinforcer was paired with JWH-018 administration only twice. Three “recovery” sessions where unflavored milk reinforced responding were interposed between each CTA trial. An additional group of mice (an “unpaired” control group) were identically trained to respond for unflavored milk presentations and tested with flavored milk. These animals were also injected with 3.0 mg/kg JWH-018 after the first two flavored milk sessions, but these injections occurred at least 10 h after the sessions ended, and were administered in the colony room.

Place conditioning

Place conditioning was accomplished using Panlab 3-compartment spatial discrimination chambers (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) consisting of a box with two equally-sized conditioning compartments connected by a corridor. The compartments were differentiated by visual pattern on the walls, color, floor texture, and shape, providing multiple contextual dimensions across sensory modalities. An initial pre-conditioning preference test was first conducted, in which mice were allowed to explore the apparatus for 30 min, and the last 15 min of behavior was recorded and scored. Over the next two days, mice were housed in the colony room and assigned to receive drug on their non-preferred side and saline in their preferred compartment. The conditioning phase began with mice receiving a saline injection and being confined to their preferred compartment for 30 min. After the saline conditioning trial, mice were removed and returned to their home cage. Mice were injected with 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg JWH-018, or with 3.0 mg/kg of the psychostimulant SR(±)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, as a non-cannabinoid positive control) 4h later, and confined to their non-preferred compartment for 30-min. Thus, mice were conditioned with both saline and drug each day, for 4 total trials with each injection condition. A 15-min post-conditioning preference test occurred the day after the final conditioning trial. The entire test was recorded and scored, but was otherwise conducted in a manner identical to the pre-conditioning preference test previously described.

Drugs

JWH-018 was synthesized by Thomas Prisinzano, Ph.D. (University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS) and provided as a generous gift to the investigators. Δ9-THC and SR(±)-MDMA were supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, Bethesda, MD). MDMA was dissolved in physiological saline, while both cannabinoids were dissolved in a vehicle consisting of absolute ethanol : emulphor : physiological saline at a ratio of 1 : 1 : 18. All drug solutions were stored at 4°C until used, and all injections were administered i.p. at a constant volume of 0.01 ml/g.

Data Analysis

Because inter-subject variability in response rates was relatively high in CTA experiments, response rates during aversion trials were transformed to percent of unflavored milk control, by dividing each individual trial rate by that subject’s mean rate on the previous 3 “milk recovery” days, then multiplying by 100. Rates for each trial were compared using a oneway repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s HSD test for all possible pairwise comparisons. For CPP studies, a preference (or aversion) score was calculated by subtracting the pre-conditioning test time spent in the compartment which was subsequently paired with drug administration from time spent in that same compartment during the postconditioning test. Preference/aversion scores were not normally distributed, so comparisons across groups were accomplished using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks, followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Statistical significance was judged at p < 0.05.

Results

Conditioned taste aversion

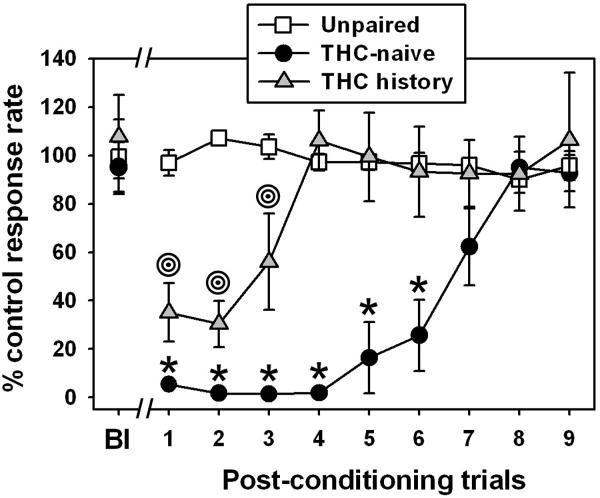

During the first (pre-pairing baseline) session in which the flavored milk reinforcer was available, mice in all groups responded at high rates, which were not different from control rates observed in sessions where the unflavored milk was available (Figure 1, “Bl” points). For the group in which the flavored milk reinforcer was not paired with JWH-018 administration (Figure 1, open squares), response rates across trials did not significantly differ from the baseline observation (p>0.05 for all comparisons.) The range of mean rates for this group varied from a low of 90.04 ± 5.48 % to a high of 107.16 ± 2.88 % across all trials. In contrast, mice pre-exposed to the cannabinoid vehicle only (Figure 1, filled circles) exhibited dramatically reduced response rates for the flavored milk reinforcer paired with JWH-018 administration during the first 6 aversion trials (q=10.95, 11.36, 11.41, 11.35, 9.71 and 8.66, respectively, and p<0.001 for all comparisons), but recovered completely by the 8th trial (q=0.80, p>0.05). Interestingly, mice pre-exposed to the escalating Δ9-THC regimen (Figure 1, grey triangles) displayed a blunted taste aversion to the flavored milk reinforcer paired with JWH-018 administration. For these animals, response rates were significantly reduced during only the first 3 aversion trials (q=8.32, 8.81 and 6.00, respectively, and p<0.001 for all comparisons), and completely recovered by the 4th trial (q=0.60, p>0.05). Furthermore, the degree of response rate suppression was significantly less in Δ9-THC-treated mice than observed in vehicle-treated mice on trials 1-3 (q=3.33, 3.250 and 6.10, respectively, p < 0.05 for all comparisons.)

Figure 1.

Conditioned taste aversion elicited by two administrations of 3.0 mg/kg JWH-018 in mice previously exposed to an escalating dose regimen of Δ9-THC, or in THC-naïve animals. Horizontal axis: Post-conditioning trials where the JWH-018-paired flavor was contingently available. “Bl” indicates the first (baseline) presentation of this novel flavor, prior to pairing with JWH-018. The first JWH-018 administration occurred immediately after this baseline session, and the final JWH-018 injection occurred immediately after post-conditioning trial 1. Vertical axis: Mean (±SEM) response rate maintained by the JWH-018-paired flavor, expressed as percent of the control response rate maintained by the unflavored milk reinforcer. Absence of error bars indicates that the variability is contained within the data point. Bullseyes indicate significant differences from the THC history Bl condition, while asterisks indicate significant differences from the THC-naïve Bl condition and from the THC history group, as determined by one-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

Place conditioning

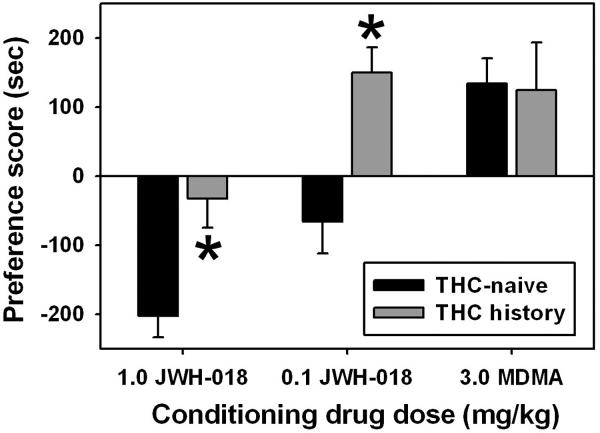

Administration of JWH-018 elicited dose-dependent effects on place conditioning. The high JWH-018 unit dose (1.0 mg/kg/inj) resulted in a negative preference score in mice previously exposed to the drug vehicle only (Figure 2, filled bars), indicative of a conditioned place aversion. These apparent aversive effects were blunted in mice previously treated with the escalating Δ9-THC regimen (Figure 2, open bars), and the between-group difference was significant at this high JWH-018 unit dose (q=3.60, p<0.05.) The low JWH-018 unit dose (0.1 mg/kg/inj) also produced a negative preference score in mice previously exposed to the drug vehicle only (Figure 2, filled bars), but elicited a positive preference score, indicative of a conditioned place preference, in mice previously treated with the escalating Δ9-THC regimen (Figure 2, open bars). The between-group difference was also significant at this low JWH-018 unit dose (q=4.10, p<0.05.) Importantly, the escalating Δ9-THC regimen did not alter the apparent appetitive effects of a 3.0 mg/kg/inj unit dose of MDMA (p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Place conditioning effects of 4 administrations of 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg JWH-018, or 3.0 mg/kg MDMA, in mice previously exposed to an escalating dose regimen of Δ9-THC, or in THC-naïve animals. Horizontal axis: Drug and unit dose used in afternoon place conditioning sessions, in mg/kg. Vertical axis: Mean (±SEM) preference score, calculated as the difference between time spent in the drug-paired compartment during the post-conditioning test and time spent in that compartment during the pre-conditioning test, in seconds. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the THC-naïve and THC history groups, as determined by Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on ranks and Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies demonstrating aversive effects of cannabinoids in cannabinoid-naïve subjects (Fischer and Vail, 1980; Switzman et al., 1981), the present CTA studies also demonstrate profound aversive effects after only a single pairing of 3.0 mg/kg JWH-018 and a novel flavor (‘post-conditioning trial 1’) in mice with no prior cannabinoid history. These aversive effects were persistent, as responding for the JWH-018-paired flavor did not return to baseline levels until post-conditioning trial 7 or 8, although a “floor effect” may certainly be involved in the prolonged recovery observed in these animals. In contrast, mice previously treated with the escalating Δ9-THC dose regimen exhibited significantly blunted taste aversion, where response rates in these subjects were no lower than 30% of control, and returned to baseline levels faster than the Δ9-THC-naïve group.

Previous reports also show that Δ9-THC pre-exposure is required to unveil apparent rewarding effects of Δ9-THC in the CPP assay in mice (Valjent and Maldonado, 2000; Valjent et al., 2002; Castañe et al., 2003), and our present CPP results extend this observation to the high efficacy synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018, but not to the non-cannabinoid drug of abuse MDMA.

Presumably, the learned association between a novel context and the interoceptive stimulus properties of the paired drug interacts with pharmacological history to dictate both the magnitude and directionality of the place conditioning effect. Interestingly, mice conditioned with JWH-018 without a prior Δ9-THC history avoided the drug-paired compartment in a dose-dependent manner during post-conditioning tests – a result generally thought to indicate that the drug has aversive stimulus properties (Bardo and Bevins, 2000).

The major finding of the present research is thus that a history of Δ9-THC “protects” against aversive effects and “unmasks” apparent rewarding effects of the high efficacy synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 in mice. In contrast, JWH-018 elicited dramatic and persistent aversive effects in Δ9-THC-naïve animals in the CTA procedure, and induced only conditioned place aversion in the CPP procedure. These results suggest that cannabinoid-naïve individuals using K2/”Spice” products may be at increased risk for adverse reactions, perhaps requiring medical intervention (e.g., Muller et al., 2010; Vearrier and Osterhoudt 2010; Schneir et al., 2010). On the other hand, those with a history of marijuana use may be particularly sensitive to the appetitive effects of high efficacy cannabinoids present in these commercial smoking blends, perhaps leading to escalated use and dependence (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2009; Nacca et al., 2013). These suppositions are supported by a recent case series documenting no adverse reactions to K2/”Spice” use in three regular marijuana smokers meeting DSM-IV-TR cannabis dependence criteria (Gunderson et al., 2012).

Among the cannabinoids, tolerance to numerous in vivo effects is readily induced across species (reviewed in Adams and Martin, 1996), so cross-tolerance between Δ9-THC and JWH-018 could be at least partially responsible for the presently observed attenuation of apparent aversive effects. Indeed, cross-tolerance between Δ9-THC and high efficacy synthetic cannabinoids has been reported in humans (Gunderson et al., 2012), nonhuman primates (Hruba et al., 2012), and mice (Fantegrossi et al., 2013). It has been proposed that the “hedonic effects” of a drug are determined by a relative balance between appetitive and aversive effects (Riley, 2011); thus, tolerance to aversive effects would be expected to alter this balance in favor of appetitive effects, perhaps explaining the “unmasking” of apparent rewarding effects of JWH-018 in the present CPP experiments. Alternatively, Δ9-THC-induced changes in learning (c.f. Davis and Riley, 2010) or reward sensitization (c.f. Robinson and Berridge, 2008) could also account for the effects presently reported.

As states and municipalities within the US consider normalizing recreational marijuana use, it is important to emphasize that the synthetic cannabinoids present in K2/“Spice” products are often much more potent and efficacious drugs than the phytocannabinoids present in the marijuana plant. Our present results also suggest that high efficacy synthetic cannabinoids are likely to elicit aversive effects in drug-naïve individuals, but these aversive effects may be attenuated in those with a history of cannabis use, allowing some apparent rewarding effects to be “unmasked.” This has implications not only for drug abuse and dependence, but also for the ongoing debate regarding deregulation of marijuana use and control of emerging synthetic cannabinoids present in readily-available smoking blends.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute [Grant RR029884] and by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Center for Translational Neuroscience [Grant RR020146]. WSH received a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) from the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics to conduct this research, and received a SURF travel award to present portions of this work at the 2012 Experimental Biology conference in San Diego, CA.

References

- Adams IB, Martin BR. Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction. 1996;91(11):1585–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood BK, Huffman J, Straiker A, Mackie K. JWH018, a common constituent of ‘Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB receptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:585–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology. 2000;153(1):31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Reichard EE, Zimmerman SM, Moran JH, Fantegrossi WE, Prather PL. Phase I hydroxylated metabolites of the K2 synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 retain in vitro and in vivo cannabinoid 1 receptor affinity and activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:c21917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Zimmerman SM, Saffell AR, Prather PL, Fantegrossi WE. Differential drug-drug interactions of the synthetic Cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073: implications for drug abuse liability and pain therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346(3):350–61. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.206003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañé A, Robledo P, Matifas A, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome is reduced in double mu and delta opioid receptor knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17(1):155–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CM, Riley AL. Conditioned taste aversion learning: implications for animal models of drug abuse. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1187:247–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Franks LN, Vasiljevik T, Prather PL. Tolerance and cross-tolerance among high-efficacy synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073 and low-efficacy phytocannabinoid Δ9-THC. FASEB J. 2013;27:1097–1. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer GJ, Vail BJ. Preexposure to delta-9-THC blocks THC-induced conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Neural Biol. 1980;30(2):191–6. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)91065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EW, Haughey HM, Ait-Daoud N, Joshi AS, Hart CL. “Spice” and “K2” herbal highs: a case series and systematic review of the clinical effects and biopsychosocial implications of synthetic cannabinoid use in humans. Am J Addict. 2012;21:320–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruba L, Ginsburg BC, McMahon LR. Apparent inverse relationship between cannabinoid agonist efficacy and tolerance/cross-tolerance produced by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol treatment in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342(3):843–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Primack BA, Barnett TE, Cook RL. College students and use of K2: an emerging drug of abuse in young persons. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller H, Huttner HB, Köhrmann M, Wielopolski JE, Kornhuber J, Sperling W. Panic attack after Spice abuse in a patient with ADHD. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2010;43:152–153. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacca N, Vatti D, Sullivan R, Sud P, Su M, Marraffa J. The synthetic cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome. J Addict Med. 2013;7:296–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31828e1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL. The paradox of drug taking: the role of the aversive effects of drugs. Physiol Behav. 2011;103(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Review. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1507):3137–46. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneir AB, Cullen J, Ly BT. “Spice” girls: Synthetic cannabinoid intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:296–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Switzman L, Fishman B, Amit Z. Pre-exposure effects of morphine, diazepam and delta 9-THC on the formation of conditioned taste aversions. Psychopharmacology. 1981;74(2):149–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00432682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Maldonado R. A behavioural model to reveal place preference to delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2000;147:436–8. doi: 10.1007/s002130050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Mitchell JM, Besson MJ, Caboche J, Maldonado R. Behavioural and biochemical evidence for interactions between Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and nicotine. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135(2):564–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R, Dunn KE, Fry JA, Girling ER. A survey study to characterize use of Spice products (synthetic cannabinoids) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:238–241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardakou I, Pistos C, Spiliopoulou C. Spice drugs as a new trend: mode of action, identification and legislation. Toxicol Lett. 2010;197:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vearrier D, Osterhoudt KC. A teenager with agitation: Higher than she should have climbed. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:462–465. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e4f416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann US, Winkelmann PR, Pilhatsch M, Nees JA, Spanagel R, Schulz K. Withdrawal phenomena and dependence syndrome after the consumption of “Spice Gold.”. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:464–467. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]