Abstract

The isolation of plasmid-protein relaxation complexes from bacteria is indicative of the plasmid nicking-closing equilibrium in vivo that serves to ready the plasmids for conjugal transfer. In pC221 and pC223, the components required for in vivo site- and strand-specific nicking at oriT are MobC and MobA. In order to investigate the minimal requirements for nicking in the absence of host-encoded factors, the reactions were reconstituted in vitro. Purified MobA and MobC, in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+, were found to nick at oriT with a concomitant phosphorylation-resistant modification at the 5′ end of nic. The position of nic is consistent with that determined in vivo. MobA, MobC, and Mg2+ or Mn2+ therefore represent the minimal requirements for nicking activity. Cross-complementation analyses showed that the MobC proteins possess binding specificity for oriT DNA of either plasmid and are able to complement each other in the nicking reaction. Conversely, nicking by the MobA proteins is plasmid specific. This suggests the MobA proteins may encode the nicking specificity determinant.

The transfer of plasmids between bacterial cells by conjugation is the result of two processes: mating-pair formation between the donor and recipient, and DNA processing reactions, which prepare the plasmid for transfer (38). In keeping with the generalized models of DNA processing based on gram-negative systems, conjugation can proceed only after a site- and strand-specific cleavage at a unique nick site (nic) within an origin of transfer (oriT). The transesterification reaction is catalyzed by a relaxase (transesterase) within a nucleoprotein complex, the relaxosome, in the presence or absence of accessory proteins. A single strand is unwound by a host or plasmid-encoded helicase and transferred with a 5′-to-3′ polarity to the recipient cell (15).

The DNA processing components of several gram-negative conjugative and mobilizable plasmids, e.g., RP4, pTiC58, F, R388, and R1162/RSF1010 have been genetically and biochemically characterized in vitro. This facilitates the determination of the minimal components and confirms roles and specificities of factors otherwise identified in vivo (15, 38). In contrast, conjugative and mobilizable plasmids of gram-positive bacteria are comparatively under-represented (8).

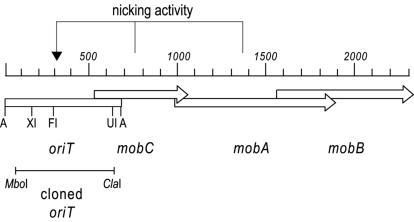

Plasmids pC221 and pC223 are small (4.6 kb), low-copy-number chloramphenicol resistance plasmids and are mobilizable members of the rolling-circle replicating small staphylococcal plasmid family. They contain four genetic loci involved in their mobilization: the cis-acting locus origin of transfer (oriT) and the overlapping trans-acting loci mobC, mobA, and mobB (Fig. 1) (33). An oriT region, functional in mobilization assays, has been broadly defined on an intergenic 692-bp AluI fragment (28, 36).

FIG. 1.

Functional organization of the mobilization region of pC221 consisting of oriT, mobC (nicking accessory protein), mobA (DNA relaxase), and mobB (mobilization accessory protein). The target of the mobC and mobA gene products is indicated. Restriction enzyme sites are indicated as follows: A, AluI; XI, BstXI; FI, BsrFI; and UI, BstUI.

Site- and strand-specific nicking of pC221 and pC223 in vivo requires mobA, mobC, and superhelical oriT, the positions of which have been determined (33). The nic regions share significant similarity with relaxase family 1 consensus nic regions, which (like the corresponding relaxase alignments) include those of RP4 and the pTiC58 right-border sequence, representing the strong link between relaxase families and nic site groupings (25). In addition, the oriT regions of pC221 and pC223 have been exchanged in vivo. This results in a loss of nicking activity (33). The precise determinant of oriT specificity has yet to be determined; it may be the gene products of mobC, mobA, an unknown host-encoded factor, or a combination of these. Similar complementation experiments have been performed between IncPα plasmids RP4 and R751. RP4 relaxosome components do not form at R751 oriT in vitro (22), however heterologous relaxosome components of R751 were able to produce relaxation complexes at RP4 oriT in vivo if the RP4 traJ gene was present, indicating that TraJ is involved in substrate specificity (5).

In several systems, additional host-encoded factors are required for stabilization or regulation. In F, the DNA structural change due to integration host factor (IHF) binding is required in addition to the plasmid encoded accessory protein TraYp to mediate cleavage by TraI (10). In R388, IHF inhibits cleavage in vivo; thus, it acts as a regulator with its removal stimulating the nicking process (17).

MobA of pC221 and pC223 have previously been classified into the family 1: VirD2-related relaxases, which include TraI of RP4 and VirD2 of pTiC58 (23, 11, 12). In contrast to relaxase alignments, the various accessory proteins align poorly between the plasmid groups and yet are often found encoded adjacent to the relaxase in plasmid mobilization regions in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. A potential conserved motif within a number of MobC homologues from gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria has been identified (L/FxxxG/SxNxNQxAxxxN), although no function has yet been assigned (1).

Accessory proteins such as MobC of R1162 have been proposed to act as “molecular wedges,” denaturing oriT strands up to and including the nic site, thus providing a single-stranded substrate for the relaxase (39). RP4 encodes three accessory proteins, one of which, TraJ, is believed to act as a recognition signal for nucleosome assembly at oriT (41), which has also been proposed as the function of VirD1 of pTiC58 (30); a second accessory protein, TraK, acts as a stimulatory enhancer of nicking by binding downstream of the nic site potentially resulting in increased single-stranded character of strands at the nic site (42). Others, such as TrwA of R388 (17) and TraYp of F (18), act as stimulatory enhancers of cleavage by their relaxases.

pC221 and pC223 provide simple systems embodying the initial events in DNA processing reactions and are also the first examples of mobilizable plasmids subjected to genetic and biochemical characterization in staphylococci. In addition, genetic and biochemical characterization of mobilizable plasmids specifically in gram-positive bacteria currently extend only to the RCR plasmid pMV158 (7). To date, in vitro reconstitution of relaxosomes in the mobilizable pC221 family has not been shown. We report here the purification of the MobA and MobC proteins of pC221 and pC223 from overproducing strains of Escherichia coli. We provide data, with pC221 as a prototype, on the initial characterization of the MobA relaxase and MobC accessory proteins. Finally, we demonstrate functional reconstitution and properties of the pC221 and pC223 relaxosomes with site- and strand-specific nicking of oriT in vitro and provide observations of substitution and specificity in Mob protein cross-complementation experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and DNA manipulations. Standard methods were used for DNA isolation and modification (29). The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pC221cop903 contains deletions in the copy number control region and was used in preference to wild-type pC221 due to its high copy number. The mobilization region sequence is identical to that of pC221. Plasmid constructs were prepared in E. coli DH5α; plasmids used for protein expression were transformed into E. coli B834 (λDE3, pLysS).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Strains | ||

| B834 | F−, ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm met (λDE3); pLysS (Cmr) | Novagen |

| DH5α | F−, φ80dlacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, λ− | Novagen |

| S. aureus RN4220 | Attenuated, mecA, TSSE−, restriction-deficient, modification-proficient derivative of strain +8325-4; pC221cop903/pC223 host | 13 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pC221cop903 | 4,168 bp: Cmr; inc4, repD, mobCAB, (Δ806-1185; copy no. mutation) | 27 |

| pC223 | 4,608 bp: Cmr, inc10, repJ, mobCAB | 20 |

| pET15b | 5,708 bp: Apr, ColE1ori, PRT7lac | Novagen |

| pET23a | 3,666 bp: Apr, oriFI oriColE1, PRT7 | Novagen |

| pET22b | 5,493 bp: Apr, oriFI oriColE1, PRT7lac, pelB | Novagen |

| pET-H6MobC-221 | 6,084 bp: pET15b with pC221 cop903 His6-mobC | This work |

| pET-H6MobC-223 | 6,181 bp: pET15b with pC223 His6-mobC | This work |

| pET-MobAH6-221 | 4,535 bp: pET23a with pC221 mobA-His6 | This work |

| pET-MobAH6-223 | 6,357 bp: pET22b with pC223 mobA-His6 | This work |

| pCER19 | 3,063 bp: pUC19: Apr; ColE1ori, lacZ, cer dimer resolution sequence | C. D. Thomas |

| pCER21T | 3,575 bp: pCER19 containing pC221 cop903 oriT | This work |

| pCER23T | 3,584 bp: pCER19 containing pC223 oriT | This work |

Abbreviations: Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Novagen, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

PCR amplification of insert material was performed by using Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene) and reaction buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 2. Plasmids pET-H6MobC-221 and pET-H6MobC-223 were created by inserting mobC PCR products from pC221 and pC223, respectively, into the expression vector pET15b (Novagen) via NdeI/BamHI, creating a fusion to an N-terminal His6 tag. Plasmids pET-MobAH6-221 and pET-MobAH6-223 were created by inserting mobA PCR products from pC221 and pC223 into the expression vectors pET23a and pET22b via NdeI/XhoI, creating a fusion to a C-terminal His6 tag. All constructs were verified by DNA sequence analysis.

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Restriction enzyme (strand orientation) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21NforMOBC | GGAATTCATATGAGTGAATATGATAATAATTTGG | NdeI (+) | Cloning of pC221 mobC |

| 21BrevMOBC | CGGGATCCCTAATTTAGTTGTTGCCATATTTC | BamHI (−) | Cloning of pC221 mobC |

| 23NforMOBC | GGAATTCCATATGAGTGAACATGATAATAATTTGG | NdeI (+) | Cloning of pC223 mobC |

| 23BrevMOBC | CGGGATCCTCTATATCACAATTCAAAG | BamHI (−) | Cloning of pC223 mobC |

| 21NforMOBA | GGAATTCCATATGGCAACAACTAAATTAG | NdeI (+) | Cloning of pC221 mobA |

| 21XrevMOBA | GGGCTCGAGTCTCGAAAGTCCTTCGTCGCC | XhoI (−) | Cloning of pC221 mobA |

| 23NforMOBA | GGAATTCCATATGGCAACAACTAAAATAAGC | NdeI (+) | Cloning of pC223 mobA |

| 23XrevMOBA | GGGCTCGAGTTCAAGCTCCAGCTTCGGAG | XhoI (−) | Cloning of pC223 mobA |

| 21BforORIT | CGGGATCCCGCAAGTGATCATAAAATTTATG | BamHI (+) | Cloning of pC221 oriT |

| 21PrevORIT | GGGCTGCAGAATCGATTGTCGCGTTTC | PstI (−) | Cloning of pC221 oriT |

| 23BforORIT | CGGGATCCCTTCATAAACTTAAGTAATCATG | BamHI (+) | Cloning of pC223 oriT |

| 23PrevORIT | GGGCTGCAGAATCGATTGTCGCGTCTC | PstI (−) | Cloning of pC223 oriT |

| HPA+150 | CACTCATTCAATCCCACC | (+) | Primer extension expts |

| HPA−130 | GAACGTATAGCAACCAC | (−) | Primer extension expts |

Nucleotides that are underlined denote engineered restriction endonuclease tags.

Primers were designed to amplify the oriT regions of both pC221cop903 and pC223 between the MboI restriction site located nearest to the end of the CAT gene in each plasmid and the ClaI restriction site in the respective mobC genes (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 9). PCR fragments were inserted via BamHI/PstI into pCER19 (a derivative of pUC19 carrying the cer site of ColE1 inserted as a 377-bp HpaII fragment via the NarI site of pUC19) (Table 1). Substrate plasmid DNA for nicking experiments was purified by using CsCl-ethidium bromide density centrifugation.

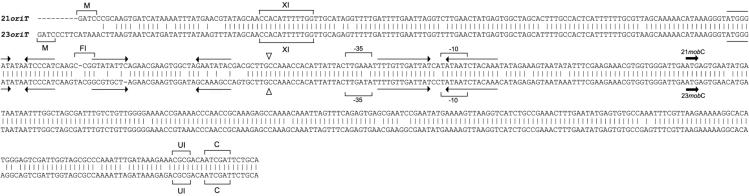

FIG. 9.

Alignment of the pC221 and pC223 oriT sequences. The upper sequence, 21oriT, is the ClaI/MboI fragment of pC221 cloned into pCER. The lower sequence, 23oriT, is from the corresponding region of pC223. Sequences were aligned by using CLUSTAL X (37). Vertical lines indicate sequence identity. The “▿” symbol indicates the nic site. The predicted −10 and −35 promoter sequences are indicated by brackets. Arrows represent inverted repeats. Heavy arrows indicate the mobC start codon. The restriction enzyme sites—M, MboI; XI, BstXI; FI, BsrFI; UI, BstUI; and C, ClaI—correspond to those in Fig. 1. Sequences are as defined previously (33).

Overexpression and purification of recombinant Mob proteins.

Cells harboring the expression vectors were grown overnight in 5 ml of 2YT broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml), and 1% (vol/vol) glucose at 37°C. A 1/1,000 dilution of overnight culture was inoculated into fresh 2YT broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 and then grown aerobically at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6. IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to final concentrations of 0.15 mM for induction of H6MobC or 0.4 mM for MobAH6, and expression was continued for 4 h. Cells were harvested at 9,700 × g for 10 min, and dried pellets were stored at −20°C for 1 h.

Cells were resuspended in one-tenth the original culture volume of buffer A: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.5 M KCl or 0.6 M KCl for H6MobC or MobAH6, respectively. Lysis was completed by sonication with a MSE Soni-Prep 150 (Sanyo), and the soluble fraction, after centrifugation at 21,800 × g for 30 min, was retained. His6-tagged proteins were purified by using Chelating Sepharose Fast-Flow (Pharmacia) charged with 100 mM NiSO4 and equilibrated with 8% buffer B (buffer A plus 400 mM imidazole [pH 8.0]). H6MobC and MobAH6 elution was achieved with a gradient of 8 to 100% buffer B over 25 to 30 column volumes. Protein elution was monitored at A280 by spectroscopy. Peak elution fractions were analyzed by electrophoresis on 12.5% or 15% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels followed by Coomassie blue staining to assess homogeneity of purified protein. Fractions containing pure protein were extensively dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-10% glycerol-1 mM EDTA containing 0.2 M or 0.5 M KCl for storage of H6MobC and MobAH6, respectively, by using a 15-ml, 3,000 molecular-weight-cutoff Slide-A-Lyzer cassette (Pierce) and then stored in 1-ml aliquots at −20°C. When necessary, proteins were concentrated by using 50- or 5-ml stirred ultrafiltration pressure cells (Amicon) with presoaked YM10 membranes and a cell pressure of 45 lb of N2/in2 (3.2 kg/cm2). H6MobC and MobAH6 concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at a λmax of 276 nm based on their predicted molar extinction coefficients (6).

Terminal peptide sequencing of Mob proteins.

N-terminal and C-terminal protein sequencing was provided by the University of Leeds Biomolecular Analysis Facility.

Analytical ultracentrifugation.

Sedimentation velocity experiments and equilibrium sedimentation experiments were performed at a temperature of 10°C in an Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.).

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments on H6MobC221 and MobAH6221 were performed by using 1.2-cm-pathlength six-sector cells loaded with 125-μl samples in Beckman four-place An-60 Ti and 8-place An-50 analytical rotors, respectively. The data for H6MobC221 were collected at speeds of 15,000 and 18,000 rpm. The data for MobAH6221 were collected at 10,000 rpm for 66 h, then at 11,000 rpm for a further 23 h, and finally at 12,000 rpm for a further 18 h. Radial absorbance scans at a wavelength of 275 nm (10 replicates, radial step size = 0.001 cm) were performed at 6-h intervals. Scans were judged to be at equilibrium after 55 h at 10,000 rpm by the absence of movement between scans made at 6-h intervals. Centrifugation was extended for a further 8 h at 45,000 rpm, and the resulting absorbance at the meniscus was used as a fixed baseline-offset correcting for nonsedimenting absorbance due to low-molecular-weight material and optical defects in the system. The data were analyzed by least-squares nonlinear regression by using XL-A/XL-I Data Analysis Software Version 4.0 by Beckman based on the program Origin (Microcal Software, Inc., Northampton, Mass.). The partial specific volumes of H6MobC221 (0.715 ml/g) and MobAH6221 (0.714 ml/g) and the buffer densities and viscosities were calculated by using the freeware program SEDNTERP (Thomas Laue, Department of Biochemistry, University of New Hampshire, Durham).

Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out using 1.2-cm pathlength 2-sector aluminum centerpiece cells loaded with 420 μl of sample in one sector and a reference solution of dialysis buffer in the other. The data were collected at a speed of 55,000 rpm, and changes in solute concentration were detected by 212 Rayleigh interference scans and 188 absorbance scans at 275 nm. Sedimentation data were analyzed by g(s*) analysis (34) to provide the apparent distribution of sedimentation coefficients with the program DCDT+ v1.13 (26). Sedimentation and diffusion coefficients were allowed to float during the fit. Whole boundary analysis was performed by using the program Sedfit v8.0 (32). Axial ratios of the proteins were estimated by the Teller method (35), as implemented by SEDNTERP.

Specific interaction of pC221cop903 and pC223 MobC with oriT.

pCER21T (containing pC221 oriT) and pCER23T (containing pC223 oriT) DNA was digested with BstXI and HindIII restriction endonucleases to yield fragments of 2,789 bp, 494 bp (containing oriT), and 292 bp. Purified, digested DNA (0.4 μg) was incubated with either H6MobC221 or H6MobC223 at various concentrations, in total volumes of 30 μl containing 100 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 5 mM MgCl2. After incubation at 30°C for 45 min, reaction mixtures were loaded on 0.8% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE)-agarose gels. After electrophoresis at 5 V/cm for 100 min, gels were stained with ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) for 30 min and then destained for 20 min in 1× TBE. Gel images were captured digitally using a GDS-8000 gel documentation system (UVP).

In vitro reconstitution of relaxosomes. Reaction mixtures of MobAH6 (11.7 pmol), H6MobC (3 pmol), and 0.18 pmol of supercoiled (FI) plasmid DNA were incubated in a total volume of 30 μl containing 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 5 mM MgCl2 for 60 min at 30°C. Relaxed intermediates were captured by the addition of EDTA (25 mM), SDS (0.3% [vol/vol]), and Bacillus griseus protease (pronase) (100 μg/μl), followed by incubation at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction products were analyzed electrophoretically on 0.8% TAE-agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml). Gel images were captured digitally, and band intensities were quantified with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). The yield of nicked open-circular (FII) DNA, expressed as %FII, was calculated after correction for the relative fluorescence of FII to FI DNA (1.5:1 for pC221 and 1.57:1 for pCER19 and derivatives).

Polynucleotide kinase reactions.

pC221cop903 DNA (1 pmol), either FII or FI, was digested with the enzymes BstXI and BstUI. The resulting fragments were cleaned by using a Nucleotide Cleanup Column (Qiagen), heat denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and immediately chilled on ice. Then, 75 fmol of DNA was treated with 12.5 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen) in a phosphate exchange reaction for 14 min at 37°C in the presence of [γ-33P]ATP (15 μCi) in a final volume of 7 μl. Reactions were stopped by incubation at 65°C for 10 min and the addition of 3.5 μl of formamide loading dye (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.02% Xylene Cyanole FF). Samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min prior to electrophoresis through a 6% (vol/vol) polyacrylamide-8 M urea-1× TBE sequencing gel by using 1× TBE as running buffer. Gels were exposed to a PhosphorImager plate and scanned by using a BAS1000 Bio-Imaging Analyzer (Fujix; Fuji).

Mapping of the nick site.

Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (33) with the use of [α-35S] dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) (ICN Biomedicals) as a label, BsrFI-digested FI pC221cop903 as a terminal transferase control, and 7-deaza-dGTP in place of dGTP being the only modifications. Products were separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis as described above.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of Mob proteins.

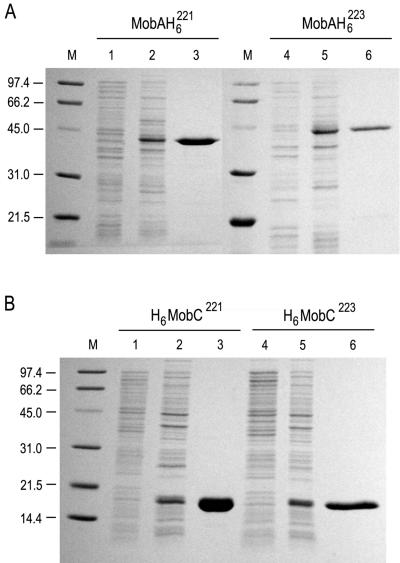

The genes coding for the MobA and MobC proteins of both pC221 and pC223 were amplified by PCR and cloned into pET expression vectors. To facilitate purification, these genes were expressed as His6-tagged fusion proteins. These fusions add 20 amino acids (aa) to the N terminus of MobC: the products are designated H6MobC221 (147 aa; 16.8-kDa predicted molecular mass) and H6MobC223 (152 aa; 17.4 kDa) for proteins derived from pC221 and pC223, respectively. The C-terminal fusions add 8 aa to the MobA proteins: the products are MobAH6221 (323 aa; 37.5 kDa) and MobAH6223 (338 aa; 39.9 kDa). All proteins were purified to >95% homogeneity after metal ion chelating chromatography (Fig. 2), yielding 8 to 9 mg of purified protein per liter of induced culture. Although ≥50% of the overexpressed MobAH6 was present in an insoluble form, sufficient soluble material was present to achieve the stated yields of active protein. Both the purity and biological activity of H6MobC and MobAH6 were monitored at each step of purification by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and double-stranded DNA nicking assays. The molecular masses of the expressed recombinant proteins were comparable to those predicted.

FIG. 2.

Polyacrylamide gel analysis of pC221 and pC223 Mob proteins. Samples were electrophoresed on 12.5% (MobA) and 15% (MobC) (wt/vol) polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels containing 0.1% SDS. Protein bands were stained with Coomassie blue R-250. (A) MobA purification; (B) MobC purification. Lanes 1 and 4, uninduced cells; lanes 2 and 5, induced cells; lanes 3 and 6, purified protein. M, Molecular mass marker (Bio-Rad Low Range). Masses are indicated in kilodaltons.

Physicochemical properties of the Mob proteins.

The identity of the two overproduced MobA proteins was verified by N-terminal sequencing. The sequences were Ala-Thr-Thr-Lys-Leu-Gly-Asp and Ala-Thr-Thr-Lys-Ile-Ser-Ser for MobAH6221 and MobAH6223, respectively, indicating the loss of the N-terminal methionine in each case. The C-terminal 5 aa residues of H6MobC221 and H6MobC223 were confirmed as Trp-Gln-Gln-Leu-Asn-COOH and Trp-Gln-Gln-Leu-Lys-COOH, respectively. Both MobA and MobC proteins favored high-salt buffers for storage, possibly reflecting the relatively high in vivo physiological ionic strength of S. aureus (3). Removal of the His6 tags from MobC proteins by thrombin cleavage did not alter the physical or biological properties of the proteins (data not shown).

Analytical ultracentrifugation was used to determine oligomerization state and predominant oligomeric forms. H6MobC221 has low absorbance in UV light due to a low percentage of aromatic residues; sedimentation velocity and equilibrium experiments performed at the protein concentration used in the nicking assay yielded poor quality data when the absorbance values at 220 and 275 nm were measured. Experiments were therefore performed on 50 μM solutions of the protein. Sedimentation velocity experiments indicated that the dominant species was dimeric with an S (20*,w) value of 2.41 S and a corresponding mass of 28.23 kDa. The frictional ratio ƒ/ƒo of 1.53 and axial ratio of ∼5.5, with a hydration expansion of 16.51%, can be modeled to an anisometric prolate ellipsoid. Sedimentation equilibrium was used to confirm the oligomerization state of H6MobC221. The apparent molecular mass of 33.7 kDa was consistent with a dimer of 16.8 kDa. The data was best fitted to a two-species model for a dimer-tetramer interconversion with a weak self-association to the tetrameric form (Kd = 708 μM).

Sedimentation velocity and equilibrium experiments of MobAH6221 were performed with protein concentrations of 400 nM to 24 μM and at speeds of 10,000 to 12,000 rpm. The data indicated a high degree of polydispersity, which at best was indicative of monomer, tetramer, and hexamer oligomers that were stable and non-self-associative. The nature of this distribution dispersity made analysis for potential self-associations insecure.

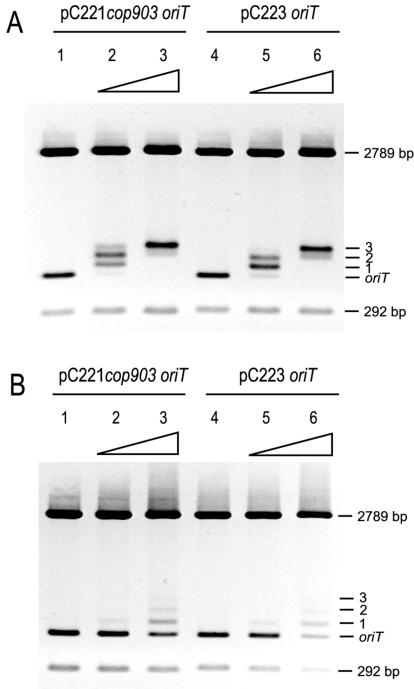

MobC specifically binds oriT DNA sequences.

Accessory proteins in a number of transfer systems have been shown to bind specifically to oriT containing DNA, e.g., TraJ of RP4 (41) and TraYp of F plasmid (10). The MobC proteins, like many DNA-binding proteins, are basic (calculated pI = 9.11 to 9.78) and exist as dimers in solution. DNA-specific binding properties were assessed by agarose gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

To facilitate the study of the oriT regions of pC221cop903 and pC223, these regions were cloned via MboI/ClaI into a pUC19 derivative (see Materials and Methods). These plasmids were subsequently digested with BstXI/HindIII releasing oriT within a 494-bp fragment containing 8 bp derived from the vector and two fragments (2,789 and 292 bp) that acted as competitor DNAs. Purified H6MobC221 or H6MobC223 were assayed against both their respective cognate and noncognate oriT substrates. The electrophoretic mobilities of both oriT fragments decreased in the presence of either MobC protein (Fig. 3). There was no nonspecific retardation of the competitor DNAs indicating that MobC specifically recognizes oriT DNA. Three isoforms of MobC-oriT complex were observed with increasing concentrations of protein, suggesting multiple binding sites or more complex modes of binding. At higher concentrations, no further stable isoforms were observed; only nonspecific binding to all three fragments (data not shown). At comparable concentrations, H6MobC223 resulted in a lower proportion of bound species of either oriT than the H6MobC221, indicating lower affinity for the DNA. However, this interpretation assumes that our H6MobC223 is fully active.

FIG. 3.

EMSA to assess complex formation between oriT DNA and MobC protein. oriT fragments of pC221 and pC223 were released from pCER21T and pCER23T by digestion with BstXI and HindIII as 494-bp fragments with two competitor fragments of 2,789 and 292 bp. (A) EMSA in the presence of pC221 MobC protein. Lanes 1 and 4, DNA alone; lanes 2 and 5, 175 nM MobC; lanes 3 and 6, 350 nM MobC. (B) EMSA in the presence of pC223 MobC protein. Lanes 1 and 4, DNA alone; lanes 2 and 5, 300 nM MobC; lanes 3 and 6, 2 μM MobC. Negative images of the ethidium bromide-stained gels are shown. All protein concentrations are given with respect to the monomer.

Reconstitution of the pC221 and pC223 relaxosomes.

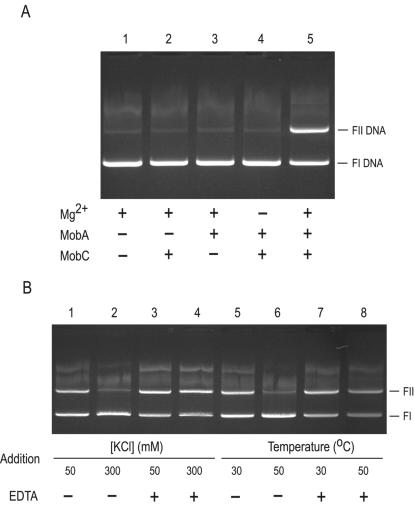

To confirm whether the mobA and mobC gene products induce the site- and strand-specific nic observed in vivo, purified components MobAH6 and H6MobC were combined with supercoiled plasmid DNA containing a cognate oriT sequence in vitro, with a buffer containing Mg2+ ions. After incubation, nicked forms were captured by the addition of EDTA and incubation with pronase and SDS. In the absence of either protein component or divalent cation, no nicking activity was observed (Fig. 4A). These constituents therefore represent the minimal requirements for nicking activity in vitro. The in vitro nicking reactions typically yielded 40 to 55% nicked, open circular (or FII) DNA, comparable to that observed in vivo (20, 28, 33) and those observed with TraI-TraJ of RP4 (22), MobM of pMV158 (9), and TrwC of R388 (16).

FIG. 4.

In vitro reconstitution of the nicking reaction. (A) Reactions were constructed in the absence of each of the required constituents in turn and finally with all reaction constituents. Reactions were prepared and terminated as described in Materials and Methods and electrophoresed in a 0.8% 1.0× TBE agarose gel at 7 V/cm. Lanes 1 to 5, pC221cop903 as substrate. H6MobC221 (0.1 μM) was present in lanes 2, 4, and 5. MobAH6221 (0.39 μM) was present in lanes 3, 4, and 5. MgCl2 (5 mM) was present in lanes 1, 2, 3, and 5. (B) Salt- and temperature-dependent activity. Standard reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 min before the addition of KCl (lanes 2 and 4) or the temperature was increased (lanes 6 and 8), followed by incubation for an additional 90 min. Duplicate reactions were performed with EDTA (25 mM) added immediately prior to increasing the salt concentration (lanes 3 and 4) or temperature (lanes 7 and 8).

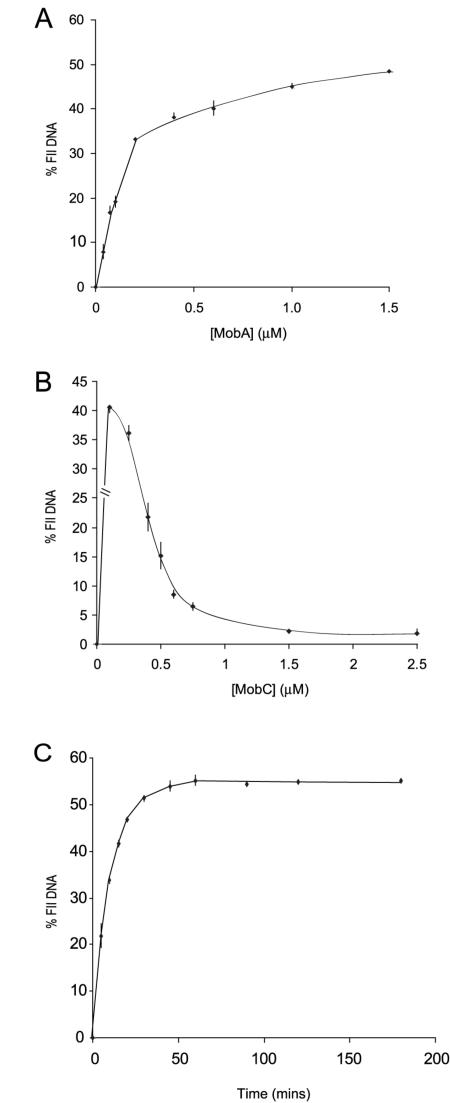

The amount of FII DNA obtained was dependent on the concentration of both MobA and MobC proteins. Titration with MobA (Fig. 5A) resulted in an increase in %FII material approaching an equilibrium distribution of FII DNA. Higher concentrations did not significantly alter this distribution. Titration against MobC protein (Fig. 5B) indicated maximal activity at lower concentrations, with a significant inhibitory effect at higher concentrations. At optimal concentrations of MobA and MobC (see Materials and Methods), a typical nicking-closing distribution of 55% was achieved within 1 h, with no observable increase in FII as the reaction was prolonged, reflecting the establishment of equilibrium between FI and FII DNA (Fig. 5C). Varying the pH between 7.0 and 9.0 did not significantly affect the observed nicking activity; the optimal temperature was 30°C, with reactions yielding less FII nicked product at 10 to 20°C or 37 to 42°C, and no nicked products at all were observed after incubation at 0 or 50°C (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Variation in % FII DNA resulting from altered reaction conditions. (A) Nicking reactions containing 0.1 μM of H6MobC221 and 5 mM MgCl2 were titrated with increasing amounts of MobAH6221; (B) nicking reactions containing 0.39 μM MobAH6221 and 5 mM MgCl2 were titrated with increasing amounts of H6MobC221; (C) nicking reactions were terminated at the time points indicated. Error bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate experiments. All protein concentrations are given with respect to monomer.

Nicking activity was dependent on the presence of Mg2+, although substitution with Mn2+ also resulted in comparable yield of FII material. Ca2+ could also be substituted, but with a 40% reduction of nicked product. No nicking activity was observed with the alternative divalent cations Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, or Ba2+ (data not shown).

The nicking reaction was sensitive to ionic strength and did not proceed in the presence of more than 200 mM KCl. Indeed, the subsequent addition of salt to 300 mM KCl (or an increase in temperature to 50°C) resulted in complete reversal of the equilibrium in favor of FI material. However, such reversal was not observed if Mg2+ ions were first chelated by EDTA, indicating an Mg2+-dependent religation activity as observed with MobA, MobB, and MobC of RSF1010 (31) (Fig. 4B).

The nicking reaction crucially had an absolute requirement for superhelical substrate DNA. No nicking activity was observed when the pC221cop903 substrate DNA was either linearized with HindIII or relaxed with staphylococcal topoisomerase IV prior to the addition of MobA and MobC (data not shown).

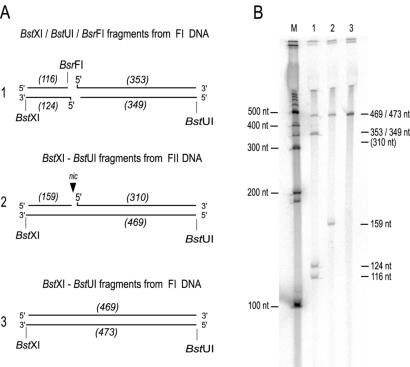

The 5′ end at nic is resistant to phosphorylation.

With the exception of TraI of CloDF13 (21), all relaxase-mediated transesterification reactions characterized to date result in a blocked 5′ end at nic that is resistant to phosphorylation (15). To determine whether our MobA was covalently attached to the 5′ end of nic, FII pC221cop903 produced in the nicking reaction was cleaved with BstXI and BstUI. The resulting nicked and digested DNA was used as a substrate 5′ end for labeling with [γ-33P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Fig. 6A). A control sample of FI DNA, digested with the same enzymes, presents four possible 5′ ends as substrates for phosphorylation, resulting from two fragments of 3,699 and 469 bp (Fig. 6A). Electrophoresis of nicked, digested DNA resulted in the expected bands at 3,699 and 469 bp but also yielded a band of 159 bp corresponding to the distance between the BstXI cleavage and nic (Fig. 6B). The absence of a band corresponding to the 310-bp fragment of the nicked strand between nic and BstUI indicated that the 5′ end is indeed blocked after SDS capture of nicked FII DNA and is resistant to phosphorylation.

FIG. 6.

The pC221cop903 nic 5′ end is resistant to phosphorylation. (A) Overview of expected BstXI/BstUI fragment of pC221cop903 after cleavage with BsrFI or nicking by MobA subsequently 5′ end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase; (B) autoradiograph of fragments after separation on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. M, 100-bp ladder. Lane 1, pC221cop903 cut with BsrFI before BstXI/BstUI digestion; lane 2, nicked FII material cut with BstXI/BstUI; lane 3, FI DNA cut with BstXI/BstUI.

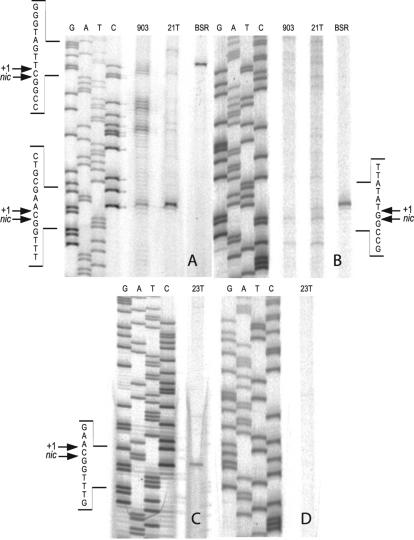

MobA and MobC catalyze a site- and strand-specific cleavage in vitro.

The location of the strand discontinuity introduced by MobA was determined by using T7 Sequenase polymerase in a primer extension reaction with primers designed to anneal 150 bp upstream or 130 bp downstream from the BsrFI restriction site (Table 1). Negatively supercoiled pC221cop903 digested at this site was also used as a control for terminal transferase activity of the polymerase; this was found to result in primer extension products 1 nucleotide longer (+1) than predicted for the site of cleavage within the template strand. If this is taken into account, the results are consistent with a nic in the sense strand of oriT, with respect to the Mob open reading frames, but not at the corresponding position in the complementary strand. The determined nic sites for the cloned pC221cop903 and pC223 oriTs nicked with their cognate MobA and MobC proteins were 3147CTTG/CCAA3154, and 1866CTTG/CCAA1873, respectively (Fig. 7). These strand discontinuities exactly match the site and strand characteristics determined for nic in vivo.

FIG. 7.

Mapping of the 5′ end of the single-stranded nick at oriT in vitro. Gels A and B show primer extension products on pC221 oriT plus and minus strands, respectively. Lanes: 903, primer extension with nicked pC221cop903 as a template; 21T, nicked pCER21T as a template; BSR, BsrFI-cleaved pCER21T as a template. Gels C and D show the result from primer extension assays on pC223 oriT plus and minus strands, respectively. Lane 23T, nicked pCER23T as a template. Sequencing ladders (G, A, T, and C) used the same primer and negatively supercoiled plasmid for of the adjacent DNA as a template. “+1” indicates the primer extension product against the sequence in the opposing strand: the actual site of cleavage is one nucleotide further along.

Specificity and cross-complementation of Mob proteins.

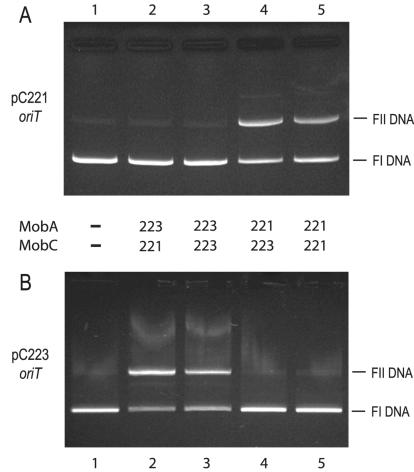

The individual DNA sequence specificities of MobA and MobC proteins were investigated by cross-complementation analysis with pC221cop903 and pC223 oriT substrates with all possible combinations of cognate and/or noncognate MobA and MobC (Fig. 8). Both MobAH6223 and MobAH6221 were found to nick their respective cognate oriT sequences in the presence of either cognate or noncognate MobC proteins (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 and 5, and B, lanes 2 and 3) but were unable to nick noncognate oriT sequences irrespective of the source of MobC protein (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 3, and B, lanes 4 and 5). The pC223 oriT was nicked to a greater degree by its cognate relaxase than the pC221 oriT.

FIG. 8.

Cross-complementation of Mob proteins on cognate and noncognate substrates. Nicking reactions containing equal concentrations of the respective cognate and noncognate proteins were prepared and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cross-complementation with pC221 oriT as a substrate; (B) cross-complementation with pC223 oriT as a substrate. 221 and 223 denote proteins from pC221 and pC223, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have shown that the MobC and MobA proteins of plasmids pC221 and pC223 are sufficient to form a nicked relaxation complex in vitro at the oriT of these plasmids, in the presence of divalent metal ions such as Mg2+. The location of the nick site, and demonstration of plasmid specificity conferred by the MobA component, are in agreement with observations made in vivo (33). Thus, we offer the relaxosome of pC221 as a model system for the in vitro study of the DNA processing steps that precede the mobilization of small staphylococcal plasmids.

The features of the complex parallel observations made with other systems. The assignment of MobA as a relaxase has been made previously, based upon the amino acid sequence motifs conserved in such proteins (23). The catalytic requirement for Mg2+ has been previously noted as a requirement in both DNA cleavage and rejoining mechanisms in all relaxases (25). Substitution with Mn2+ has been noted for the relaxases of RP4 (24), pMV158 (9), pIP501 (14), and R388 (16). Both MobA (11, 12, 23) and the sequence at the nick site (33) are related to the family 1 relaxases. The product of the nicking reaction is blocked against 5′ phosphorylation, indicating residual covalent attachment of protein via a phosphodiester bond as documented in almost all systems studied so far (38), and the cleavage reaction may be reversed by the addition of salt as observed in plasmid RSF1010 (31) and R100 (4). Although the cleavage of single-stranded DNA substrates by MobA has yet to be demonstrated, pC221 resembles the IncP-related relaxosome in that the relaxase alone is unable to nick double-stranded negatively supercoiled DNA in vitro; an accessory protein, MobC, must also be supplied for this to occur (22).

The pC221 MobC protein shares physical properties with other accessory proteins: it is small in size (14.6 kDa) with a basic pI of 9.11. The hydrodynamic studies indicate that it is a prolate ellipsoid that is predominantly dimeric at the concentrations required to form the relaxosome. Like the dimeric RP4 accessory protein TraJ (41), it binds to its related oriT sequence in an EMSA in the absence of the corresponding relaxase (5). However, whereas TraJ is able to distinguish between its cognate oriT and that of the closely related IncP plasmid R751 (5), we note that the closely related MobC proteins are unable to distinguish between the related, but nonidentical, oriT fragments of pC221 and pC223 (Fig. 9). This finding comes as a surprise, since the pC221 and pC223 relaxosomes have been shown to form in a plasmid-specific manner in vivo (33), and the MobA protein alone does not show any DNA binding under such conditions (data not shown). Although the staphylococcal MobC proteins show distant sequence homology to other accessory proteins (1), their sequences do not reveal any conserved DNA-binding motifs, such as the ribbon-helix-helix motif found in the unrelated TraY of the IncF plasmids (19), compared to online databases such as PROSITE (2). The same is also true of TraJ of RP4 (41).

The two MobC proteins of pC221 and pC223 are interchangeable with regard to oriT specificity in the nicking assay, although it should be noted that the latter protein does show reduced affinity for DNA in the mobility shift assay. However, the three distinct bands that result from this assay indicate that both proteins bind to the DNA in a similar manner, potentially in a cooperative fashion utilizing multiple binding sites within oriT. Given the juxtaposition of oriT and the MobC reading frame (the distance from the nic site to initiation codon is only 92 nucleotides) (Fig. 9), such higher-order complexes may also be involved in the autoregulation of transcription through mobCAB, a strategy observed previously in TraYp of F, TraJ and TraK of IncPα plasmid RK2 (15), TrwA of IncW plasmid R388 (17), and MobA, MobB, and MobC of R1162 (40). Since relaxosome formation is inhibited at high concentrations of MobC, it is likely that these higher-order complexes prevent entry of MobA into the relaxosome complex. A similar observation was made with excess binding of TraK to the RP4 oriT in vitro (42) and to an extent with TraI, TraY, and IHF on linear F plasmid oriT (18).

MobA may contribute the specificity required to discriminate between pC221 and pC223. However, as stated above, MobA alone fails to demonstrate sequence-specific DNA binding, nor does it possess recognizable DNA-binding signatures beyond the conserved motifs of the relaxase. However, whereas the two MobC proteins exhibit high sequence identity throughout their length, the two MobA proteins diverge significantly beyond the first 122 aa encompassing the relaxase motifs. Thus, the C-terminal sequence of the proteins may provide a sequence discriminatory function and possibly also an interface for the very dissimilar MobB proteins encoded by the two plasmids, which although unnecessary for relaxosome formation are essential for mobilization (28, 33).

Also unlike MobC, an increased concentration of the relaxase increases the relative yield of FII DNA in the nicking assay; the dispersed nature of MobA in hydrodynamic studies precludes assignment of such yields to any given multimeric state. It has not yet been possible to demonstrate a direct interaction between MobA and MobC proteins by gel filtration or formaldehyde cross-linking in the absence of DNA (data not shown); the interchangeability of MobC components demonstrates that MobA does not discriminate between accessory proteins to the same extent that it does with oriT. Thus, it is not yet known how MobC facilitates the entry (and activity) of MobA to the relaxosome. Precedents include localized strand denaturation, which may serve to present an accessible cleavage target as observed with MobC of R1162 (39); a DNA bending/allosteric alteration, suggested for TraYp/IHF in F plasmid (18); and presentation of a combined protein-DNA docking interface for recruitment of the relaxase, as proposed for TraJ of RP4 (41). The latter is an attractive model for pC221, since the reversal of nicking activity may result from a weaker affinity of MobC for oriT (and hence dissociation) at higher salt concentrations.

Thus, the pC221 relaxosome provides a counterpart for the study of multicomponent gram-positive DNA processing reactions in vitro. The mechanisms by which both MobA and MobC recognize the origin of transfer remain uncharacterized. However, continued study should yield a greater understanding of the assembly and structure of this relaxosome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Ashworth for nucleotide sequencing, Emma Stanley for oligonucleotide synthesis, Jeff Keen for peptide sequencing, and Andy Baron for assistance with analytical ultracentrifugation.

J.A.C. and M.C.A.S. were supported by postgraduate studentships from the BBSRC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apisiridej, S., A. Leelaporn, C. D. Scaramuzzi, R. A. Skurray, and N. Firth. 1997. Molecular analysis of a mobilizable theta-mode trimethoprim resistance plasmid from coagulase-negative staphylococci. Plasmid 38:13-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bairoch, A. 1992. PROSITE: a dictionary of sites and patterns in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:2013-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian, J. H. B., and J. H. Waltho. 1962. Solute concentrations within cells of halophilic and non-halophilic bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 65:506-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda, H., and E. Ohtsubo. 1995. Large scale purification and characterization of TraI endonuclease encoded by sex factor plasmid R100. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21319-21325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furste, J. P., W. Pansegrau, G. Ziegelin, M. Kroger, and E. Lanka. 1989. Conjugative transfer of promiscuous IncP plasmids: interaction of plasmid-encoded products with the transfer origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1771-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill, S. C., and P. H. von Hippel. 1989. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grohmann, E., L. M. Guzman, and M. Espinosa. 1999. Mobilisation of the streptococcal plasmid pMV158: interactions of MobM protein with its cognate oriT DNA region. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:707-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grohmann, E., G. Muth, and M. Espinosa. 2003. Conjugative plasmid transfer in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:277-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman, L. M., and M. Espinosa. 1997. The mobilization protein, MobM, of the streptococcal plasmid pMV158 specifically cleaves supercoiled DNA at the plasmid oriT. J. Mol. Biol. 266:688-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard, M. T., W. C. Nelson, and S. W. Matson. 1995. Stepwise assembly of a relaxosome at the F plasmid origin of transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28381-28386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilyina, T. V., and E. V. Koonin. 1992. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes, and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3279-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koonin, E. V., and T. V. Ilyina. 1993. Computer-assisted dissection of rolling circle DNA replication. Biosystems 30:241-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurenbach, B., D. Grothe, M. E. Farias, U. Szewzyk, and E. Grohmann. 2002. The tra region of the conjugative plasmid pIP501 is organized in an operon with the first gene encoding the relaxase. J. Bacteriol. 184:1801-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanka, E., and B. M. Wilkins. 1995. DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:141-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llosa, M., G. Grandoso, and F. de la Cruz. 1995. Nicking activity of TrwC directed against the origin of transfer of the IncW plasmid R388. J. Mol. Biol. 246:54-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moncalián, G., M. Valle, J. M. Valpuesta, and F. de la Cruz. 1999. IHF protein inhibits cleavage but not assembly of plasmid R388 relaxosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1643-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson, W. C., M. T. Howard, J. A. Sherman, and S. W. Matson. 1995. The traY gene product and integration host factor stimulate Escherichia coli DNA helicase I-catalyzed nicking at the F plasmid oriT. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28374-28380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson, W. C., and S. W. Matson. 1996. The F plasmid traY gene product binds DNA as a monomer or a dimer: structural and functional implications. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1179-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novick, R. 1976. Plasmid-protein relaxation complexes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 127:1177-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuñez, B., and F. de la Cruz. 2001. Two atypical mobilization proteins are involved in plasmid CloDF13 relaxation. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1088-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pansegrau, W., D. Balzer, V. Kruft, R. Lurz, and E. Lanka. 1990. In vitro assembly of relaxosomes at the transfer origin of plasmid RP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6555-6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pansegrau, W., and E. Lanka. 1991. Common sequence motifs in DNA relaxases and nick regions from a variety of DNA transfer systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pansegrau, W., W. Schroder, and E. Lanka. 1993. Relaxase (TraI) of IncP alpha plasmid RP4 catalyzes a site-specific cleaving-joining reaction of single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:2925-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pansegrau, W., and E. Lanka. 1996. Enzymology of DNA transfer by conjugative mechanisms. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 54:197-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philo, J. S. 2000. A method for directly fitting the time derivative of sedimentation velocity data and an alternative algorithm for calculating sedimentation coefficient distribution functions. Anal. Biochem. 279:151-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Projan, S. J., J. Kornblum, S. L. Moghazeh, I. Edelman, M. L. Gennaro, and R. P. Novick. 1985. Comparative sequence and functional analysis of pT181 and pC221, cognate plasmid replicons from Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 199:452-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Projan, S. J., and G. L. Archer. 1989. Mobilization of the relaxable Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pC221 by the conjugative plasmid pGO1 involves three pC221 loci. J. Bacteriol. 171:1841-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Scheiffele, P., W. Pansegrau, and E. Lanka. 1995. Initiation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA processing. Purified proteins VirD1 and VirD2 catalyze site- and strand-specific cleavage of superhelical T-border DNA in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 270:1269-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherzinger, E., R. Lurz, S. Otto, and B. Dobrinski. 1992. In vitro cleavage of double- and single-stranded DNA by plasmid RSF1010-encoded mobilisation proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:41-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuck, P. 2000. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 78:1606-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, M. C. A., and C. D. Thomas. 2004. An accessory protein is required for relaxosome formation by small staphylococcal plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 186:3363-3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stafford, W. F., III. 1992. Boundary analysis in sedimentation transport experiments: a procedure for obtaining sedimentation coefficient distributions using the time derivative of the concentration profile. Anal. Biochem. 203:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teller, D. C. 1973. Characterization of proteins by sedimentation equilibrium in the analytical ultracentrifuge. Methods Enzymol. 27:346-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas, W. D., Jr., and G. L. Archer. 1992. Mobilization of recombinant plasmids from Staphylococcus aureus into coagulase negative Staphylococcus species. Plasmid 27:164-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zechner, E. L., F. de la Cruz, R. Eisenbrandt, A. M. Grahn, G. Koraimann, E. Lanka, G. Muth, W. Pansegrau, C. M. Thomas, B. M. Wilkins, and M. Zatyka. 2000. Conjugative-DNA transfer processes, p. 87-174. In C. M. Thomas (ed.), The horizontal gene pool: bacterial plasmids and gene spread. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 39.Zhang, S., and R. Meyer. 1997. The relaxosome protein MobC promotes conjugal plasmid mobilization by extending DNA strand separation to the nick site at the origin of transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 25:509-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, X., S. Zhang, and R. Meyer. 2003. Molecular handcuffing of the relaxosome at the origin of conjugative transfer of the plasmid R1162. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:4762-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziegelin, G., J. P. Furste, and E. Lanka. 1989. TraJ protein of plasmid RP4 binds to a 19-base pair invert sequence repetition within the transfer origin. J. Biol. Chem. 264:11989-11994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziegelin, G., W. Pansegrau, R. Lurz, and E. Lanka. 1992. TraK protein of conjugative plasmid RP4 forms a specialized nucleoprotein complex with the transfer origin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17279-17286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]