Abstract

Background

Recently, single-port video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has been proposed as an alternative to the conventional three-port VATS for primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP). The aim of this study is to evaluate the early outcomes of the single-port VATS for PSP.

Methods

VATS was performed for PSP in 52 patients from March 2012 to March 2013. We reviewed the medical records of these 52 patients, retrospectively. Nineteen patients underwent the conventional three-port VATS (three-port group) and 33 patients underwent the single-port VATS (single-port group). Both groups were compared according to the operation time, number of wedge resections, amount of chest tube drainage during the first 24 hours after surgery, length of chest tube drainage, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain score, and postoperative paresthesia.

Results

There was no difference in patient characteristics between the two groups. There was no difference in the number of wedge resections, operation time, or amount of drainage between the two groups. The mean lengths of chest tube drainage and hospital stay were shorter in the single-port group than in the three-port group. Further, there was less postoperative pain and paresthesia in the single-port group than in the three-port group. These differences were statistically significant. The mean size of the surgical wound was 2.10 cm (range, 1.6 to 3.0 cm) in the single-port group.

Conclusion

Single-port VATS for PSP had many advantages in terms of the lengths of chest tube drainage and hospital stay, postoperative pain, and paresthesia. Single-port VATS is a feasible technique for PSP as an alternative to the conventional three-port VATS in well-selected patients.

Keywords: Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), Pneumothorax, Postoperative pain, Paresthesia

INTRODUCTION

Recently, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has come to be considered the gold standard in the treatment for primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) [1]. Most surgeons perform VATS for PSP with three or more incisions. With the evolution of the VATS technique, single-port VATS for PSP has been attempted, and its advantages have been reported. Some authors have reported that one of the advantages of single-port VATS is less postoperative pain because only one intercostal space is involved in the procedure [2]. However, the clinical feasibility of single-port VATS for PSP is not well defined because there are only a few reports on single-port VATS. In this study, we analyzed the experiences of VATS for PSP of a single surgeon (DK Kang) to evaluate the clinical feasibility and advantages of single-port VATS for PSP.

METHODS

VATS was performed for PSP in 52 patients from March 2012 to March 2013. These patients were followed up until September 2013. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of these patients.

We defined PSP as a pneumothorax without any underlying pulmonary disease. Patients who underwent the conventional three-port VATS were defined as the three-port group, and those who underwent single-port VATS were defined as the single-port group. Both groups were compared in terms of the operation time, number of wedge resections, amount of chest tube drainage during the first 24 hours after surgery, length of chest tube drainage, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain score, and postoperative paresthesia.

All patients were managed with a chest tube placement initially to relieve symptoms. A computed tomography was performed in all patients to determine the number and location of blebs and bullae. Indications for surgery were recurrent ipsilateral pneumothorax, persistent air leak (longer than 5 days), contralateral pneumothorax, and visible bullae on a chest X-ray [1,3–5]. VATS was performed under general anesthesia with a double-lumen endotracheal tube to allow one-lung ventilation. Patients were placed in the lateral decu-bitus position.

In the three-port group, a 5-mm trocar was introduced through the seventh intercostal space on the midaxillary line for inserting a video thoracoscope. Then, two additional trocars were inserted: a 12-mm trocar in the sixth intercostal space on the anterior axillary line and a 5-mm trocar in the fifth intercostal space on the posterior axillary line.

In the single-port group, a single port was made in the fifth intercostal space on the anterior axillary line. Soft tissue and intercostal muscles were retracted with a small X-shaped wound retractor to secure the intercostal space and protect the intercostal neurovascular bundle.

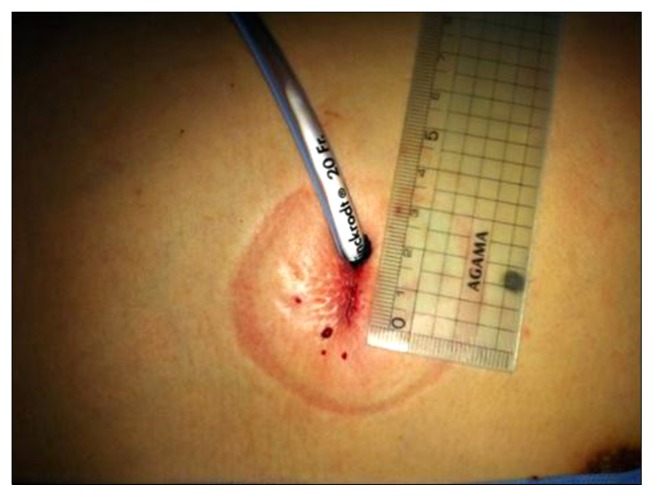

All procedures were performed with a 5-mm, 30° video thoracoscope, a 5-mm endoscopic grasper, and an endoscopic linear stapler. If there were blebs or bullae in the thoracoscopic findings, a blebectomy or bullectomy was performed. If there were no blebs or bullae, a wedge resection of the pulmonary apex was performed. A pleural abrasion was performed with sponge sticks or gauze peanuts in all patients. At the end of the procedure, a chest tube (16–20 Fr) was placed in the thoracic cavity. The chest tube was inserted through a single incision in the single-port group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Surgical wound after single-port video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax.

All patients were prescribed regular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain control after surgery. Postoperative pain was assessed by a standard visual analog pain scale (VAS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). The scores were evaluated every 24 hours until the time of discharge. We investigated the variances of the pain scores in both groups.

Differences between the two groups were assessed by means of a Student t-test. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The difference was considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using PASW SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients in both groups. There were 19 patients in the three-port group and 33 patients in the single-port group. The median follow-up duration was 15.0 months in the three-port group and 14.0 months in the single-port group. There was no difference in gender, age, affected side, and surgical indication between the two groups. There was no surgical morbidity and mortality in either of the groups. There was no conversion from single-port VATS to three-port VATS or thoracotomy.

Table 1.

The characteristics of patients in both groups

| Variable | Three-port group (n=19) | Single-port group (n=33) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.189 | ||

| Male | 18 | 27 | |

| Female | 1 | 6 | |

| Median age (yr) | 19.0 (16–30) | 18.0 (14–49) | 0.888 |

| Recurrent disease | 0.436 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 12 | |

| No | 10 | 21 | |

| Side | 0.326 | ||

| Right | 6 | 15 | |

| Left | 13 | 17 | |

| Median follow-up (mo) | 15.0 (13–18) | 14.0 (7–18) | 0.124 |

Table 2 shows the results of the surgery in both the groups. There was no difference in the number of wedge resections, operation time, and amount of drainage between the two groups. The mean length of chest tube drainage was 3.79±1.44 days in the three-port group and 2.82±0.92 days in the single-port group. The mean hospital stay was 4.47±1.35 days in the three-port group and 3.64±1.03 days in the single-port group. These differences were statistically significant. The mean VAS scores of the single-port group were lower than those of the three-port group at 24 hours after surgery and at the time of discharge. These differences were statistically significant. The VAS scores decreased progressively; however, there was no difference in the variances of the VAS scores between the two groups. Nine patients in the three-port group and three patients in the single-port group suffered from postoperative paresthesia. This was statistically significant. The mean size of the surgical wound was 2.10 cm (range, 1.8 to 3.0 cm) in the single-port group.

Table 2.

The results of surgery in both groups

| Variable | Three-port group (n=19) | Single-port group (n=33) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean no. of wedge resection | 1.58±0.61 | 1.64±0.78 | 0.784 |

| Mean operation time (min) | 41.58±9.14 | 41.21±9.10 | 0.889 |

| Mean amounts of chest tube drainage for first 24 hours after surgery (mL) | 147.89±63.30 | 119.09±9.10 | 0.137 |

| Mean length of drainage (day) | 3.79±1.44 | 2.82±0.92 | 0.004 |

| Mean hospital stay (day) | 4.47±1.35 | 3.64±1.03 | 0.015 |

| Mean visual analog scale score | |||

| At 24 hours later | 5.00±1.83 | 4.06±1.20 | 0.029 |

| At discharge | 3.21±1.48 | 1.76±0.94 | 0.001 |

| Variances | −2.05±1.31 | −2.30±1.47 | 0.541 |

| Postoperative paresthesias | 9 | 3 | 0.004 |

| Mean wound size (cm) | - | 2.10±0.28 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number.

DISCUSSION

The goals of the surgical treatment for PSP are closure of the air leak and prevention of the recurrent disease [6]. In general, most surgeons perform blebectomy/bullectomy and parietal pleurectomy/pleural abrasion. In the past, these procedures were performed through conventional thoracotomy. However, with the introduction of VATS, the treatment strategy for PSP has been changed [1]. VATS is a minimally invasive technique that has many advantages in terms of postoperative pain, recovery time, and cosmetic results. Because of its advantages, VATS is the most widely used surgical technique in patients with PSP [7]. Many authors have reported that VATS and thoracotomy yield similar results in the surgical treatment of PSP [6,8–12]. Recently, VATS represents the gold standard in the treatment for PSP [1]. Most surgeons perform VATS for PSP with three or more incisions. With the evolution of the VATS technique and the development of better thoracoscopic instruments, single-port VATS for PSP has been attempted and its advantages have been reported. Some authors have reported that one of the advantages of single-port VATS is less postoperative pain because only one intercostal space is involved in the procedure [2]. Salati et al. [13] have reported that there was less residual paresthesia in the long-term results of patients who underwent single-port VATS than in those who underwent three-port VATS.

In our study, there was no difference in the operation time and the amount of chest tube drainage. However, the mean lengths of chest tube drainage and hospital stay were shorter in the single-port group than in the three-port group. The single-port group showed more favorable results than the three-port group in terms of postoperative pain and paresthesia.

When we performed single-port VATS for PSP, the most difficult aspects were achieving the optimal lung exposure and the optimal angle for stapling blebs/bullae. Using a 30° thoracoscope and flexible staplers could be helpful in solving these problems [14]. Some surgeons performed single-port VATS without a protecting sleeve. Rocco et al. [2] reported that single-port VATS without the protecting sleeve might result in an injury to the overlying intercostal nerve and an increased need for cleaning the lens. We used a wound retractor to secure the intercostal space and protect the intercostal neurovascular bundle. The wound retractor was helpful in reducing the intercostal nerve injury by preventing direct contact between the intercostal nerve and the thoracoscopic instruments. Many trocar sleeves for single-port surgery have been introduced. Most of these trocar sleeves are for laparoscopic surgery. Because carbon dioxide has to be injected into the peritoneal space to achieve surgical vision when performing laparoscopic surgery, an airtight trocar sleeve is required. However, an airtight trocar sleeve is not required in single-port VATS, because enough space for the procedure can be secured through the one-lung ventilation. The wound retractor is available in single-port VATS as an alternative to the trocar sleeve for single-port surgery.

In our study, single-port VATS and three-port VATS yielded similar results in the surgical treatment of PSP. The single-port VATS for PSP had many advantages in terms of the lengths of chest tube drainage and hospital stay, postoperative pain, and paresthesia. Therefore, single-port VATS can be considered for PSP in well-selected patients. However, this study has certain limitations. One of the limitations was that this study was a retrospective analysis; the number of patients in each group was small and the follow-up period was short. We believe that a prospective randomized trial with a large group of patients and a long-term follow-up period is necessary to evaluate the clinical feasibility and the advantages of single-port VATS for PSP.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cardillo G, Facciolo F, Giunti R, et al. Videothoracoscopic treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a 6-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:357–61. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocco G, Martin-Ucar A, Passera E. Uniportal VATS wedge pulmonary resections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:726–8. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waller DA, Forty J, Morritt GN. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy for spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:372–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)92210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crisci R, Coloni GF. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy for recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax: a comparison of results and costs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:556–60. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(96)80424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H, Kim HK, Choi YH, Lim SH. Thoracoscopic bleb resection using two-lung ventilation anesthesia with low tidal volume for primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:880–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passlick B, Born C, Haussinger K, Thetter O. Efficiency of video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:324–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jutley RS, Khalil MW, Rocco G. Uniportal vs standard three-port VATS technique for spontaneous pneumothorax: comparison of post-operative pain and residual paraesthesia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freixinet JL, Canalis E, Julia G, Rodriguez P, Santana N, Rodriguez de Castro F. Axillary thoracotomy versus video-thoracoscopy for the treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:417–20. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayed AK, Chandrasekaran C, Sukumar M. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: clinicopathological correlation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardillo G, Carleo F, Carbone L, et al. Long-term lung function following videothoracoscopic talc poudrage for primary spontaneous recurrent pneumothorax. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:802–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikhrezai K, Thompson AI, Parkin C, Stamenkovic S, Walker WS. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery management of spontaneous pneumothorax--long-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:120–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JS, Hsu HH, Kuo SW, et al. Needlescopic versus conventional video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a comparative study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1080–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04649-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salati M, Brunelli A, Rocco G. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery for diagnosis and treatment of intrathoracic conditions. Thorac Surg Clin. 2008;18:305–10. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang DK, Min HK, Jun HJ, Hwang YH, Kang MK. Single-port video-assisted thoracic surgery for lung cancer. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;46:299–301. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2013.46.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]