Abstract

Objective

We examined the expression of IL-33 as an indicator of an innate immune response in relapsing remitting MS (RRMS) and controls. We proposed a link between the expression of IL-33 and IL-33 regulated genes to histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and in particular HDAC3, an enzyme that plays a role in the epigenetic regulation of a number genes including those which regulate inflammation.

Methods

Using TaqMan low density arrays, flow cytometry and ELIZA, expression of IL-33, and family of innate immune response genes which regulate cytokine gene expression was examined in RRMS patients and controls.

Results

Intracellular expression of IL-33 and IL-33 regulated genes are increased in patients with RRMS. In addition, following in vitro culture with TLR agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS), there is increased induction of both IL-33 and HDAC3 in RRMS patients over that seen in controls. Also, culture of PBMC with IL-33 led to the expression of genes which overlapped with that seen in RRMS patients suggesting that the gene expression signature seen in RRMS is likely to be driven by IL-33 mediated innate immune pathways. Expression of levels of IL-33 but not IL-1 (another gene regulated by TLR agonists) is completely inhibited by Trichostatin A (TSA) establishing a closer regulation of IL-33 but not IL-1 with HDAC.

Interpretation

These results demonstrate the over expression of innate immune genes in RRMS and offer a causal link between the epigenetic regulation by HDAC and the induction of IL-33.

Introduction

An inflammatory signature of the demyelinating lesions is the central feature of MS.1,2 The biochemical characteristics of the inflammatory lesion can provide a historical record of the antecedent events and thereby the genesis of the immunologic injury.2,3 In the broadest of terms, involvement of both adaptive and innate immune responses is seen in the inflammatory demyelinating lesions and is reflected in the peripheral immune system.3,4 However, studies to identify specific biochemical components which participate in immune activation in the CNS, and the agents responsible for innate immune activation in the CNS or peripheral immune system in MS have been thus far unrewarding.

In attempting to uncover the inflammatory events of CNS demyelination in relapsing-remitting MS, and determine the potential regulators of the inflammatory response, we have examined the expression and the regulation of IL-33. These studies were based on our early studies examining the gene expression profiles of MS patients which showed an increased expression of genes which participate in the innate immune response and the more recent studies showing the expression of IL-33 to be increased in MS.5–9

IL-33 is a 30KDa protein and the most recently discovered member of the IL1 cytokine gene family and involved in innate immune responses to helminthic infections.10–13 IL-33 exists as two forms, intranuclear and the secretory form in the cytosol. The N terminus of the protein has a nuclear localization signal and hence the majority of the IL-33 protein is present in the nucleus and exhibits a cellular pattern which is similar to that seen for IL-1α.14 In tissues which act as sentinels to danger such as endothelial cells and bronchial cells, IL-33 is constitutively expressed and localized to the nucleus. IL-33 has a chromatin-binding motif, which mediates the binding to histone dimers and alters the chromatic architectures suggesting that it may be involved in gene transcription and in particular, gene repression including genes which are responsible for inflammation.15,16

The active cytokine does not possess a signal peptide and, therefore, is not released through normal secretory pathways but is instead released either when the cells die or by nonconventional means and acts as an “alarmin”.17,18 Once IL-33 is released from the intracellular compartment, it binds to the heterodimeric receptor ST2/IL-1RAcp and results in the production of an innate immune response to counter the presence of danger.13,19–22

One of the key events which regulate gene activation including inflammatory genes is the architectural organization of nucleosomes that is mediated by the state of acetylation and deacetylation of lysine residues in the amino terminal tails of histones.23–25 In humans and mice, 18 histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes regulate the expression of many inflammatory and noninflammatory genes. HDAC's are grouped into four classes and HDAC3 belongs to the Class I family of HDAC's.26 Our published studies show that HDAC3 is expressed at higher levels in PBMC in MS when compared to controls.27 Also, another study has described a close relationship between the expression of HDAC3 and the induction of genes induced by activation of innate immune pathways.28 For this reason, we proposed to examine the link between the expression of IL-33, IL-33 related genes and HDAC's.

Materials and Methods

Reagents: Antibodies: CD14 PE-Cy7(clone M5E2), CD19 APC-Cy7 (clone SJ25C1) and CD3 Pacific blue (clone UCHT1) (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA); anti HDAC3 FITC (clone H-99) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti IL-1β APC (clone 8516)and anti IL-33 PE (clone 390412) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN);Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5) and Trichostatin A were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Fixation and permeabilization kits were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Human subjects

Blood and serum samples of patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) patients, healthy controls (HC), and patients with other neurological disease (OND) were recruited from the MS and general neurology clinic at Vanderbilt and from Accelerated cure project. mRNA studies on the expression of immune and cytokine genes were performed from stored blood obtained from the Accelerated Cure Project (http://www.acceleratedcure.org/about) or the MS center at Vanderbilt and stored in PAX gene tubes. The details of these samples have been reported previously.8,9,29 Flow cytometric assays were performed on freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear and serological assays on CSF and serum samples were obtained from stored samples obtained from the MS clinic. All the MS patients recruited met the criteria for clinically definite MS, who were either on treatment (MS- established), treatment naïve (MS- Naïve) or those who presented with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS).

The flow cytometric studies involving the induction of IL-33 was done on RRMS, patients, noninflammatory other neurological disease (OND) controls, and healthy volunteers. Among the 30 RRMS patients, 14 were on no treatment, 12 were receiving beta interferon, and 4 were on glatiramer acetate (Mean age, 38, M:F, 11:19). The OND group was recruited from the general neurology clinic patient population of Vanderbilt Medical center. There were 19 patients in the OND group, mean age 39.1 (M:F, 10:9), and included the following disease categories: cerebellar ataxia (2), dementia (1), seizure disorder (7), peripheral neuropathy (3), headache (3), trigeminal neuralgia(1) syringomyelia (1), and possible systemic autoimmune disease not on therapy (1). Twenty healthy volunteers were also recruited mean age 39 (M:F, 10:10). Samples for ELISA for measurement of circulating levels of IL-33 from stored samples.

mRNA transcript determination

Total RNA was purified using Qiagen's RNA isolation kits according to standard protocols and was reverse-transcribed with oligo-dT primers using Superscript III (Invitrogen). A TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA, Applied Biosystems) was designed to analyze expression levels of 24 target genes including ‘housekeeping genes’ in 300 ng cDNA. The gene probes on the TLDA plate were: ACTB, ACTR1A, APOBEC3F, ASL, B2M, CDKN1B, CSF3R, CTSS, EPHX2, EXT2, FOS, GAPDH, GATA3, GNB5, HLA-DRA, IL-11RA, LLGL2, OAS1, PGK1, PMAIP1, POU6F1, TBP, TGFBR2, and TP53. A second TLDA plate was designed to determine expression levels of genes encoding different cytokines (see text). Patient diagnosis was blinded for all experimental procedures. Relative expression levels were determined directly from the observed threshold cycle (CT). Expression levels were normalized to GAPDH according to the formula, 2(Ct test gene-Ct GAPDH).

Cultures

PBMC were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation and cultured as described in the text at 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penn/strep, and L-glutamine for 1–3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. After harvest, total RNA was purified using Tri-Reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA amounts and purity were determined by UV spectrophotometry. For the determination of expression levels of IL-33 and HDAC3, PBMC were cultured in 24-well culture plates in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL) for 16 h. The cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium containing 2 mmol glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen).

ELISA for IL-33

The levels of IL-33 in serum and CSF were measured using R&D systems DuoSet ELISA kit following the manufacturer's protocol.

Flow cytometric analysis

PBMC were collected and incubated with CD14 PE-Cy7, CD19 APC-Cy7, and CD3 Pacific blue for 30 min on ice. After washing, the cells were fixed and permeabilized according to the manufacturer's recommendation, and then were stained with HDAC3 FITC, IL-1 β APC, and IL-33 PE 30 min in the dark and analyzed on BD LSRII flow cytometer. Isotype-specific antibody was used as the negative control. Data were analyzed by BD FACSDiva software and expressed as the percentage of positive staining cells.

Statistical analysis

Prism 5 was used to present data and conduct statistical analysis. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. For correlated data sets, Pearson's rank correlation was used to assess correlation coefficients and significance. The Welch's corrected t-test not assuming equal variances was used to calculate P values in two group comparisons.

Results

Increased IL-33 mRNA expression in MS

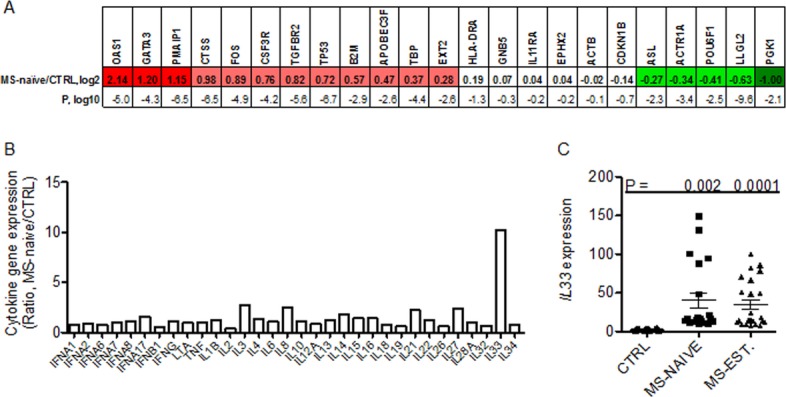

We measured transcript levels of the indicated genes in blood obtained from subjects at the initial diagnosis of RRMS prior to initiation of therapies (MS-naive). The gene probes on the TLDA plate were: OAS1, GATA3, PMAIP1, CTSS, FOS, CSF3R, TGFBR2, TP53, B2M, APOBEC3F, TBP, EXT2, HLA-DRA, GNB5, IL11RA, EPHX2, ACTB, CDKN1B, ASL, ACTR1A, POU6F1, LLGL2, PGK1. Inclusion of the specific gene targets was based upon the following criteria: (1) previous studies demonstrating differential expression among control and multiple autoimmune disease cohorts, (2) protein products possess known inflammatory functions, (3) expression levels change in response to proinflammatory stimuli (cytokines), and/or (d) protein products have known roles in cell cycle progression and/or apoptosis.5,8,30,31 Individual transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH levels and expressed as the log2 transformed [MS-naive/CTRL group] ratio. We found that the MS-naive cohort possessed a gene expression profile very different from CTRL subjects that was also very consistent among different subjects within the MS-naive cohort (Fig.1A). Of note, the P-value, log10, for OAS1 expression between the MS-naive cohort and CTRL cohort was −5.0. Similarly, expression differences in GATA3 were highly significant in the MS-naïve cohort, log10 = −4.3 and expression differences in PMAIP1 were also highly significant, log10 = −6.5. Our interpretation of these results is that each subject within the MS-naive cohort has a very similar target gene transcript profile suggesting the presence of common underlying molecular pathway(s).

Figure 1.

Gene-expression profiles in MS-naive subjects. (A) Expression levels of 23 target genes were determined by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR and normalized to expression of GAPDH. Results are expressed as the ratio of the expression level of the indicated genes in the MS-naive cohort relative to the control (CTRL) cohort, log2. Genes are identified that showed statistically significant (P < 0.05 after Bonferroni's correction for multiple testing) increased (red boxes) or decreased (green boxes) expression: CTRL, N = 100; MS-naive, N = 40. Statistical significance of the expression level of each target gene between each disease cohort and CTRL was determined using Student's t-test. P values are expressed as log10. (B) Expression levels of indicated cytokine genes were determined as in described in (A) in MS-naïve and CTRL cohorts. Results are expressed as the MS-naïve/CTRL ratio after normalization to levels of GAPDH. (C) Expression levels of IL-33 were determined in additional subjects: CTRL (N = 20), MS-naïve (N = 30) and MS-EST (N = 40). Line with error bars is the mean and S.D. P values were determined using the unpaired t-test with Welch's correction. All the MS patient materials for these experiments were obtained from the Accelerated Cure Project. The control cohort (CTRL) consisted of healthy volunteers without autoimmune disease or a family history of autoimmune disease or other chronic diseases or acute or chronic infections. The MS naïve subjects were on no immunomodulatory drugs and all the established relapsing-remitting MS patients (MS-EST) were on Glatiramer acetate. Gender distributions for all groups were 75:25 F:M and age distributions were not statistically different (Ages; CTRL: 41 ± 11, MS-naïve: 35 ± 6, MS-established: 43 ± 10)

One possible interpretation or prediction of the above results is that a cytokine or combination of cytokines drives the unique gene expression profile seen in MS-naive. Therefore, we examined expression of genes encoding different cytokines in these samples including those encoding IL-1 family member proteins, genes encoding IFN/TNF family members as well as genes encoding other cytokines. We identified a marked increase in the expression of the IL-1 family member gene, IL-33, in the MS-naive cohort (Fig.1B). Expression levels of other cytokine genes were not increased in the MS-naive cohort relative to control. Thus, among these cytokine genes, IL-33 expression was markedly increased in the MS-naïve cohort and this increase was selective for IL-33. We examined expression levels of IL-33 in additional MS-naïve subjects and in MS subjects with established disease of >1-year duration on medications, the group of clinically definite MS, (MS-EST). Levels of IL-33 were elevated in both MS-naïve and MS-EST cohorts (Fig.1C).

Intracellular expression of IL-33 protein is increased in MS

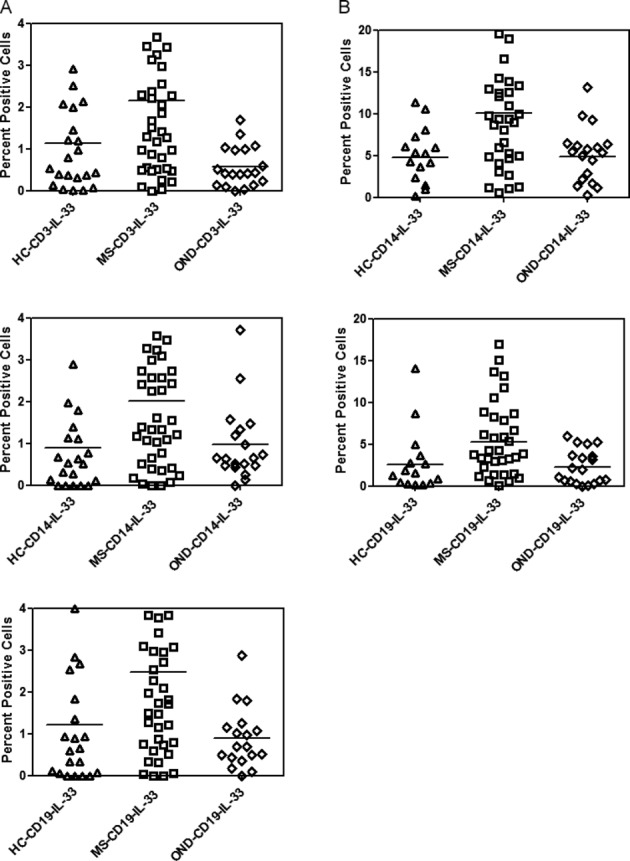

IL-33 is located mainly in the nucleus of cells and is released into extracellular spaces following either necrosis or apoptosis of cells. We, therefore, examined the constitutive levels of IL-33 in RRMS patients (N = 32) and controls (healthy controls, N = 20, OND, N = 19), in CD3, CD14 and CD19 subsets of PBMC using flow cytometry. Since corticosteroids are known to influence the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, we, therefore, did not include patients with either systemic or CNS restricted autoimmune inflammatory disease in our OND group. The amount of IL-33 expressed as a mean number of CD3+, CD14+ cells, and CD19+ cells were 2.24 ± 2.02%, 2.13 ± 1.87%, and 2.62 ± 2.17% in MS patients. All these values were significantly different (P < 0.05) when compared to IL-33 levels in controls (Fig.2A).

Figure 2.

IL-33 expression in MS. (A) Constitutive expression of IL-33 in MS, HC and OND patients in CD3+, CD14+ and CD19+ cells determined by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percent positive cells. Mean values are shown as horizontal bars, P < 0.05 between MS and controls, for all subsets examined. (B) As in (A) except PBMC were stimulated with LPS followed by intracellular cytokine staining to determine induced IL-33 expression in MS, HC and OND in CD14+ and CD19+ subsets of PBMC. Mean value are shown as horizontal bars, P < 0.05 between MS and controls, for all subsets examined. *The samples for these experiments were obtained from MS clinic at Vanderbilt.

Following stimulation of PBMC with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 16 h, there was an increase in the number of cells expressing IL-33 in the MS cohort when compared to either OND or HC cohorts. The number of IL-33 positive cells in the CD14 subset of MS patients increased from 2.13 ± 1.8% to 10.37 ± 8.24% in the CD14 subset and from 2.60 ± 2.15% in the CD19 subset of cells to 6.38 ± 5.72%. The increase in the number of IL-33 positive cells was of a lesser magnitude in the healthy controls and in the OND group and was statistically different when compared to MS patients (Fig.2B. P < 0.05 for MS versus HC and OND for CD14 and CD19 subsets). There was no difference in either the constitutive or induced level of IL-33 in patients on immunomodulatory therapy when compared to those on no therapy (Fig. S1).

Intracellular expression of IL-1β is not increased in MS

Since IL-33 belongs to the IL-1 family of cytokines we examined the constitutive and LPS-induced expression of IL-1β. Unlike IL-33, there were no differences in the constitutive expression of IL-1β among MS, HC, and OND groups (Fig.3A). We also examined the induction of IL-1β in the CD14 subset of cells between MS and controls. In the OND group, 77.7 ± 25% of CD14 cells were IL-1β positive and in the MS group the number was 79 ± 35%. These studies showed that there was no difference in the expression of IL-1β after stimulation with LPS suggesting that the increase in IL-33 was unique to the MS population.

Figure 3.

IL-1β expression in MS. (A) Constitutive expression of IL-1β in MS, HC and OND controls in CD3+, CD14+ and CD19+ cells determined by intracellular cytokine staining as in Fig.1. (B) LPS induced IL-1 β expression in CD14 and CD19 subset in MS, HC and OND controls performed as in Fig.2B. Mean values are shown as horizontal bars; there was no statistical difference in either the induced or constitutive levels of IL-1β between MS and controls.

Serum and CSF IL-33 levels are not elevated in MS patients

To determine if the intracellular level of IL-33 expression was also reflected in serum and CSF of MS patients and controls we examined the serum of I45 MS patients, 74 OND, and 23 healthy controls. The serum level of IL-33 in MS was 24 ± 85.1 pg/mL, 19 ± 47 pg/mL in OND group and 28 ± 59 pg/mL in HC. In the CSF, the level of IL-33 in MS was 14.3 ± 42 pg/mL and 5.36 ± 15.8 in OND group. There was no statistical difference in the expression of circulating IL-33 between MS and controls (Table S1).

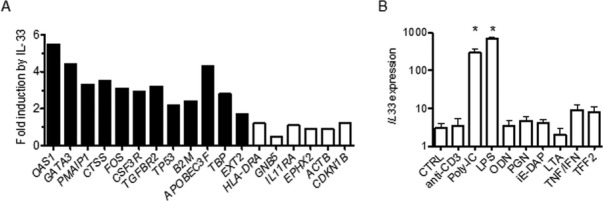

IL-33 induces a gene expression profile in PBMC similar to that in MS

To further explore the hypothesis that overexpression of IL-33 in the MS-naïve cohort was responsible for the unique gene expression profile in this cohort, we directly stimulated human PBMC (N = 4) obtained from healthy controls with IL-33 and determined changes in expression levels of MS-naïve target genes. We found that the majority of genes that were overexpressed in the MS-naïve cohort were also induced in PBMC by culture with IL-33 (Fig.4A). One known function of IL-33 is to induce increased Th2 differentiation and induction of GATA3 expression by IL-33 may explain this property of IL-33.32 Taken together, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that IL-33 overexpression, in large part, forms the unique MS-naïve expression profile but other unknown pathways may also contribute to this profile.

Figure 4.

IL-33 directly induces expression of MS related genes. (A) PBMC isolated from healthy controls were cultured with or without IL-33 (10 ng/mL) for 48 h. RNA was isolated from cultures followed by cDNA synthesis and quantitative RT-PCR to determine transcript levels of the indicated genes. Expression of individual genes was normalized to GAPDH after PBMC were cultured. Results are expressed as fold induction by IL-33 relative to untreated cultures, mean of four experiments. Filled columns; P < 0.01, open columns; P > 0.05. (B) PBMC were cultured with no stimulus or with anti-CD3, the indicated TLR agonists, lymphotoxin alpha, TNF-alpha + IFN-alpha, or TFF2 for 24–72 h. After harvest, RNA purification and cDNA synthesis, the expression level of IL-33 was determined by quantitative PCR. Results are expressed as transcript levels after normalization to GAPDH, mean of three experiments. *P < 0.01.

Next we examined the ability of different stimuli to induce IL-33 expression in human PBMC. These included anti-CD3, toll-like receptor agonists (poly-I/C, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), unmethylated CpG oligonucleotides (ODN)), the NOD1 agonists (peptidoglycan and D-gamma-Glu-mDAP dipeptide (iE-DAP)), cytokines (lymphotoxin alpha and TNF-alpha/IFN-alpha), and trefoil factor 2 (TFF2). TFF2 was included because it was one of the first factors shown to stimulate IL-33 production.32 We found that only toll-like receptor agonists, poly-I/C and LPS, but not ODN, stimulated IL-33 expression in PBMC (Fig.4B). T-cell receptor agonists, NOD1 agonists, as well as lymphotoxin alpha, TNF-alpha, and IFN-alpha did not induce IL-33 expression. TFF2 also did not stimulate IL-33 expression.

HDAC3 regulation of IL-33

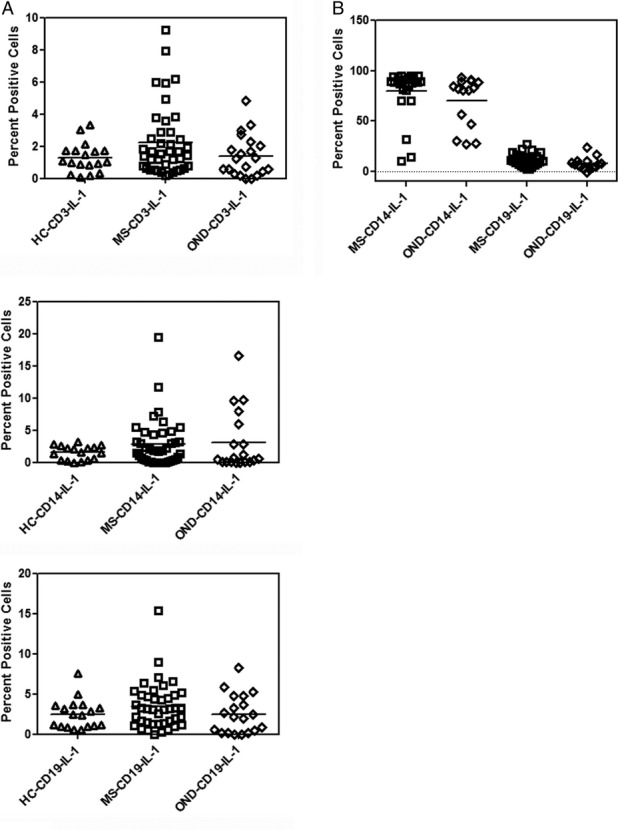

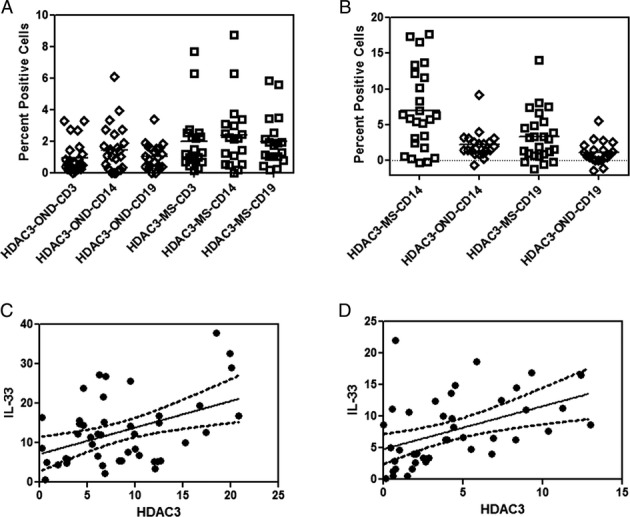

Since our previous studies showed increased expression of HDAC3 in MS patients over that seen in controls and HDAC3 expression is linked with the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, we set out to examine the relationship between the expression of HDAC3 and IL-33 in MS and compared them with other neurologic disease controls.

We found that constitutive levels of HDAC3 were elevated in MS patients when compared to controls and furthermore that these levels were increased following culture of PBMC with LPS in MS and controls. The constitutive expression of HDAC3 was statistically different between controls and MS in both the CD3 and CD19 populations. The mean percent cells expressing HDAC3 in the CD3 population was 1.97 ± 1.96% in the MS group while in the OND group it was 0.94 ± 1.00% (P = 0.02) and in CD19 subset it was 1.97 ± 1.61% in MS group as compared to 1.03 ± 0.81% in OND (Fig.5A). Although the HDAC3 expression was higher in the CD14 subset of cells in MS patients when compared to OND, it did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 5.

HDAC3 expression in MS. (A) Constitutive expression of HDAC3 in PBMC from MS, and OND controls was determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percent positive cells (P < 0.05 in MS, in CD3+ and CD19+ subsets when compared to OND). (B) Induction of HDAC3 after stimulation with LPS in RRMS and OND in CD14+ and CD19+ subset was determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percent positive cells (P < 0.05, MS CD14 and CD19 when compared to OND). Mean values are shown as horizontal bars. (C) Correlation between expression levels of IL-33 and HDAC3 after stimulation with LPS in the CD14 subset (Pearsons coefficient, r = 0.43, P < 0.01). (D) Correlation between expression levels of IL-33 and HDAC3 after stimulation with LPS in the CD19 subset (Pearsons coefficient, r = 0.40, P < 0.02).

After stimulation with LPS, there was a greater increase in the HDAC3 expressing in CD14 and CD19 subset of cells in MS, when compared to OND. The percent positive HDAC3 expressing cells were 6.53 ± 5.08% in the CD14 subset and 3.11 ± 3.18% in the CD19 subset in MS. The percent positive cells in the OND group after LPS stimulation was 2.22 ± 1.97% in the CD14 subset and 1.11 ± 1.56% in the CD19 subset (Fig.5B, P < 0.05 between MS and OND controls for CD14 and CD19 subset).

To understand the relationship between IL-33 and HDAC3, we performed a correlative analysis between induced HDAC3 expression levels in the MS cohort. We found a statistical correlation between HDAC3 expression and IL-33 in the CD14 and CD19 subset of cells (Fig.5C,D).

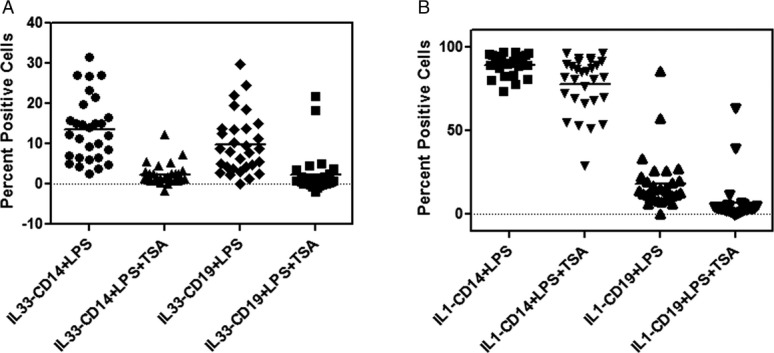

Inhibition of HDAC by TSA reduces IL-33 levels in PBMC stimulated with LPS

To determine if increased expression of IL-33 is regulated by HDAC we examined the induction of IL-33 in LPS stimulated PBMC in the presence or absence of 5 nM Trichostatin A (TSA is a known HDAC class I family of inhibitor). Preliminary studies had shown that addition of 5 nM of TSA to PBMC cultured with LPS inhibited the induction of IL-33 without impacting cell viability (Figs. S3A–C and S4). In the MS cohort there was an 84% decrease in the expression of IL-33 in CD14 subsets and 79% in CD19 subset when TSA (5 nM) was added to the culture with LPS (Fig.6A). In contrast, the inhibition of IL-1 β expression in the presence of TSA (5 nM), was reduced by 14% in CD14 cells and 22% in the CD19 subsets (Fig.6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of HDAC inhibition on IL-33 and IL-1β expression. (A) Inhibition of IL-33 expression in MS patients after addition of TSA to PBMC stimulated with LPS was determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percent positive cells [percent inhibition 84% in CD14 and 57% in CD19 cells]. (B) Inhibition of IL-1 β expression in MS patients after addition of TSA to PBMC stimulated with LPS was determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percent positive cells. Mean values are shown as horizontal bars.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate a novel relationship between IL-33 and HDAC3, a member of the HDAC class 1 family. Constitutive intracellular expression of IL-33 and HDAC3 was greater in MS when compared to controls. Also, both IL-33 and HDAC levels in PBMC were inducible following culture with LPS and these levels were also higher in MS patients when compared to controls, suggesting that PBMC from MS patients were primed to respond to TLR agonists. The complete abrogation of intracellular expression of IL-33 by TSA suggests a close and tight epigenetic regulation of IL-33 by the class I family of HDAC, a phenomenon which has hitherto been unrecognized. More importantly, the lack of inhibition of IL-1 β by TSA would suggest that a closer relationship between the expressions of IL-33 by HDAC than IL-1 β, implying that not all proinflammatory genes are equally regulated by HDAC class I family of enzymes. Interestingly, and in variance from another study increased expression of IL-33 was not seen in either the serum or CSF of MS patients when compared to controls.7 This would imply differences in the amount of IL-33 between MS patients and controls are mainly seen at intracellular level. In addition, our studies suggest that IL-33 mRNA levels are increased from the time of clinical diagnosis and the continuation of the increased level of IL-33 will require confirmation by a prospective study.

The unique pathology of the MS lesion and the undeniable role of inflammation evident in the disease has implied the existence of a pattern of inflammatory molecules, which might be specific for MS. Identification of a specific profile in MS has been difficult, in part due to the dynamic nature of the disease, the sequestration of the pathology in the CNS, and the influence of various therapies that the patients often are placed on, which cloud the interpretation of data.

Although the prevailing opinion on the pathogenesis of MS favors a central role for an adaptive T-cell response to as yet unrecognized autoantigen(s), there is evidence for a role of innate immunity in MS. Longitudinal studies have shown changes in the cytokine profile of MS patients suggesting a shift from adaptive immunity to innate immunity as a predictor of disease progression.33,34 RRMS patients who have been recently diagnosed show a gene expression pattern, which is typical of that seen following in vitro stimulation of lymphocytes with IL-33 suggesting an important role of innate immunity and in particular IL-33 in early MS as well. Since IL-33 is induced by many TLR agonists and drives the immune response in T cells toward the Th2 phenotype, it is not surprising that Th2 regulated genes are overexpressed in the gene profile of the MS patients. Although MS has been viewed as a Th1/Th17 disease, it is conceivable that the early events in MS show an overexpression of GATA3 and a prominentTh2 profile.

A general view is that activation of the innate immune system by TLR agonists leads to the induction of multiple cytokine genes and that their regulation is fairly similar. In RRMS, we find selective increased IL33 expression and in the absence of increased expression of genes that encode other cytokines involved in the innate immune response. In addition, HDAC inhibition by TSA inhibits induction of IL-33 expression by TLR agonists but does not inhibit induction of IL-1β expression to similar degrees, suggesting that distinct pathways regulate expression of these two cytokines and that HDAC inhibition may affect distinct innate immune responses. The finding that HDAC inhibitors increase susceptibility to certain bacterial and fungal infections but confer protection against toxic and septic shock supports this notion. These results also raise the possibility that IL-33 may play a critical role in these innate immune responses to bacterial and fungal infections.35

Of the many genes which are overexpressed in PBMC of RRMS and induced by IL-33 in tissue culture, elevated IL-33 in RRMS may have significant phenotypic consequences. For example, OAS1 is a prototypical IFN-response gene encoding 2′-5′oligoadenylate synthetase 1, a protein critically involved in the innate immune response to viral infection. Our results demonstrate that OAS1 is also an IL-33 response gene. The genes TP53 and PMAIP1 are also elevated in RRMS and induced by stimulation of PBMC with IL-33. Both p53 and PMAIP1 proteins cooperate to activate caspases and induce apoptosis. Thus, IL-33 may contribute to induction of apoptosis of either oligodendrocytes or cells of lymphoid/myeloid lineages by TLR agonists through induction of p53 and PMAIP1 and perhaps additional proteins that promote apoptosis.36,37

A counter regulatory role for intranuclear IL-33 has also been proposed which may be relevant to MS. Since, intracellular, but not serum levels of IL-33 expression levels are elevated in MS, it is likely that in MS, IL-33 mediates its effect at the level of gene expression rather than by IL-33/IL-33R signaling. Since IL-33, by binding to heterochromatin, has been shown to inhibit binding of NF-kB to the promotor regions of proinflammatory cytokine it appears that intranuclear IL-33 may act to put the brakes on the inflammatory response and downregulate cytokine gene expression.29

We propose that expression of HDAC and IL-33 are two overlapping mechanisms by which innate immune mediated proinflammatory signals may be regulated. HDAC's act by transcriptional repression and hence the induction of proinflammatory gene expression appears at first to be counterintuitive.38,39 Following stimulation of cells lacking HDAC3 with LPS, there is a loss of expression of over 50% of the inflammatory genes suggesting that in the normal situation, acetylation keeps inflammatory genes in a repressed state.28 More recently, HDAC3 has been shown to be necessary to activate IL-4 and loss of HDAC limits IL-4 mediated allergic disease.40 Since the loss of the inflammatory gene signature seen in macrophage cells which had not lost the expression of HDAC1 and HDAC2 or HDAC8 (HDAC class1 family), it appears that HDAC3 plays a greater role in the transcription program of proinflammatory cytokines than other members of Class I HDACs. Our studies, both published and presented here, invoke a crucial role for HDAC3 in MS. We find that the expression of HDAC3 in PBMC to be higher in MS patients when compared to controls and have suggested that overexpression of HDAC3 in MS may be linked to expression of genes that regulate inflammation and repair. In this situation, activation of HDAC3 reverses the activity of HATs and promotes release of cytokine genes from gene repression.

The relatively specific regulation of IL-33 but not IL-1β, by HDAC inhibitors is likely to offer novel therapeutic approaches to MS treatment. The assumption which is implicit in this approach is the deleterious effect of innate immune cytokines, and in particular IL-33 in inflammatory demyelinating diseases. At present, most small molecule HDAC inhibitors are directed at the larger families of HDAC enzymes and do not specifically target HDAC3. Inhibition of multiple members of the family of HDAC enzymes may result in untoward consequence.41 HDAC3 specific inhibitors, when they become available may prove useful as a therapeutic agent in inhibiting an innate immune response.

Acknowledgments

These studies were conducted from grants RG 4576A2 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and grants R42AI53948 and R01044924 from the National Institutes of Health. Also Dr. Sriram was supported by the William Weaver III and Dr. Tom West fund.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Effect of therapies on IL-33 expression levels in MS. Lack of differences in induced expression levels of IL-33 in CD14 and CD19 subsets of MS patients on therapy with those on no treatment. MS patients on therapy = 16 and on no therapy = 14.

Lack of differences in inducible expression levels of HDAC3 in CD14 and CD19 subsets between MS patients on therapy with those on no treatment.

(A–C) TSA dose-response analysis. Dose-dependent inhibition of HDAC3 (A), IL-33 (B), and IL-1β (C) by TSA, in the presence of LPS (1 µg/mL) added to PBMC cultured for 16 h and examined by flow cytometry in CD14 subset of cells. Results are pooled from experiments on three individuals.

Assessment of cell viability by Trypan blue exclusion in PBMC. Results are mean values of cell viability from three individuals maintained in culture media for 16 h. PBMCs were cultured with different concentrations of TSA for 16 h harvested for Trypan blue dye exclusion viability assay using 0.2% Trypan blue. Number of viable (unstained) and nonviable (stained) cells were counted using a hemocytometer. Viability in PBMC which did not receive TSA was 91%; addition of 1 nM and 5 nM TSA reduced viability to 80% and 81%, respectively. At higher doses of added TSA the cell viability was as follows: 10 nM = 58%, 15 nM = 51% and 50 nM=32%.

Expression levels of IL-33 in serum and CSF of MS patients, healthy controls, and patients with other neurological disease mea-sured by ELISA.

References

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann H. The architecture of inflammatory demyelinating lesion in MS: implications for studies on pathogenesis. Neuropathol Appl Neurol. 2011;37:698–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis–the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:942–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:683–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke PS, Tossberg JT, Horst SN, et al. Using gene expression data to identify certain gastro-intestinal diseases. J Clin Bioinforma. 2013;2:20. doi: 10.1186/2043-9113-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CA, Christophi GP, Gruber RC, et al. Induction of IL-33 expression and activity in central nervous system glia. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:631–643. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1207830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophi GP, Gruber RC, Panos M, et al. Interleukin-33 upregulation in peripheral leukocytes and CNS of multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Immunol. 2012;142:308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tossberg JT, Crooke PS, Henderson MA, et al. Gene-expression signatures: biomarkers toward diagnosing multiple sclerosis. Genes Immun. 2011;13:146–154. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tossberg JT, Crooke PS, Henderson MA, et al. Using biomarkers to predict progression from clinically isolated syndrome to multiple sclerosis. J Clin Bioinforma. 2013;3:18. doi: 10.1186/2043-9113-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Muto T, Kawagoe T, et al. Contribution of IL-33-activated type II innate lymphoid cells to pulmonary eosinophilia in intestinal nematode-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3451–3456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201042109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;10:103–110. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G, Gabay C. Interleukin-33 biology with potential insights into human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:321–329. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:827–840. doi: 10.1038/nrd2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere V, Roussel L, Ortega N, et al. IL-33, the IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:282–287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel L, Erard M, Cayrol C, Girard JP. Molecular mimicry between IL-33 and KSHV for attachment to chromatin through the H2A-H2B acidic pocket. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1006–1012. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzaki H, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, et al. The danger signal, extracellular ATP, is a sensor for an airborne allergen and triggers IL-33 release and innate Th2-type responses. J Immunol. 2011;186:4375–4387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchler AM, Pollheimer J, Balogh J, et al. Nuclear interleukin-33 is generally expressed in resting endothelium but rapidly lost upon angiogenic or proinflammatory activation. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1229–1242. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger KM, Sullivan BM, Locksley RM. IL-18 and IL-33 elicit Th2 cytokines from basophils via a MyD88- and p38alpha-dependent pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:769–778. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chackerian AA, Oldham ER, Murphy EE, et al. IL-1 receptor accessory protein and ST2 comprise the IL-33 receptor complex. J Immunol. 2007;179:2551–2555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HR, Milovanovic M, Allan D, et al. IL-33 attenuates EAE by suppressing IL-17 and IFN-gamma production and inducing alternatively activated macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1804–1814. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SG, Dangond F. Rationale for the use of histone deacetylase inhibitors as a dual therapeutic modality in multiple sclerosis. Epigenetics. 2006;1:67–75. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.2.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Raff M. Chromatin remodeling and histone modification in the conversion of oligodendrocyte precursors to neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2963–2972. doi: 10.1101/gad.309404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespear MR, Halili MA, Irvine KM, et al. Histone deacetylases as regulators of inflammation and immunity. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Shi Y, Wang L, Sriram S. Role of HDAC3 on p53 expression and apoptosis in T cells of patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Barozzi I, Termanini A, et al. Requirement for the histone deacetylase Hdac3 for the inflammatory gene expression program in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2865–E2874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121131109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Mohs A, Thomas M, et al. The dual function cytokine IL-33 interacts with the transcription factor NF-kappaB to dampen NF-kappaB-stimulated gene transcription. J Immunol. 2011;187:1609–1616. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas K, Chen H, Shyr Y, et al. Shared gene expression profiles in individuals with autoimmune disease and unaffected first-degree relatives of individuals with autoimmune disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1305–1314. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas K, Westfall M, Pietenpol J, et al. Reduced p53 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with loss of radiation-induced apoptosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1047–1057. doi: 10.1002/art.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills-Karp M, Rani R, Dienger K, et al. Trefoil factor 2 rapidly induces interleukin 33 to promote type 2 immunity during allergic asthma and hookworm infection. J Exp Med. 2012;209:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner HL. A shift from adaptive to innate immunity: a potential mechanism of disease progression in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-1002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Abraham M, Monsonego A, et al. Innate immunity in multiple sclerosis: myeloid dendritic cells in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis are activated and drive a proinflammatory immune response. J Immunol. 2006;177:4196–4202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger T, Lugrin J, Le Roy D, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors impair innate immune responses to Toll-like receptor agonists and to infection. Blood. 2011;117:1205–1217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Leaman DW. Involvement of Noxa in cellular apoptotic responses to interferon, double-stranded RNA, and virus infection. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15561–15568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev AG, Di Giovanni S, Wang G, et al. BOK and NOXA are essential mediators of p53-dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28367–28374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Kurdistani SK, Grunstein M. Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science. 2002;298:1412–1414. doi: 10.1126/science.1077790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Seto E. The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:206–218. doi: 10.1038/nrm2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullican SE, Gaddis CA, Alenghat T, et al. Histone deacetylase 3 is an epigenomic brake in macrophage alternative activation. Genes Dev. 2012;25:2480–2488. doi: 10.1101/gad.175950.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Chen Y, Hoang T, et al. HDAC1 and HDAC2 regulate oligodendrocyte differentiation by disrupting the beta-catenin-TCF interaction. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:829–838. doi: 10.1038/nn.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of therapies on IL-33 expression levels in MS. Lack of differences in induced expression levels of IL-33 in CD14 and CD19 subsets of MS patients on therapy with those on no treatment. MS patients on therapy = 16 and on no therapy = 14.

Lack of differences in inducible expression levels of HDAC3 in CD14 and CD19 subsets between MS patients on therapy with those on no treatment.

(A–C) TSA dose-response analysis. Dose-dependent inhibition of HDAC3 (A), IL-33 (B), and IL-1β (C) by TSA, in the presence of LPS (1 µg/mL) added to PBMC cultured for 16 h and examined by flow cytometry in CD14 subset of cells. Results are pooled from experiments on three individuals.

Assessment of cell viability by Trypan blue exclusion in PBMC. Results are mean values of cell viability from three individuals maintained in culture media for 16 h. PBMCs were cultured with different concentrations of TSA for 16 h harvested for Trypan blue dye exclusion viability assay using 0.2% Trypan blue. Number of viable (unstained) and nonviable (stained) cells were counted using a hemocytometer. Viability in PBMC which did not receive TSA was 91%; addition of 1 nM and 5 nM TSA reduced viability to 80% and 81%, respectively. At higher doses of added TSA the cell viability was as follows: 10 nM = 58%, 15 nM = 51% and 50 nM=32%.

Expression levels of IL-33 in serum and CSF of MS patients, healthy controls, and patients with other neurological disease mea-sured by ELISA.