Abstract

Objective

The importance of the built environment for physical activity has been recognized in recent decades, resulting in new research. This study aims to understand the current structure of physical activity and built environment (PABE) research and identify gaps to address as the field continues to rapidly develop.

Methods

Key PABE articles were nominated by top scholars and a snowball sample of 2,764 articles was collected in 2013 using citation network links. Article abstracts were examined to determine research focus and network analysis was used to examine the evolution of scholarship.

Results

The network included 318 PABE articles. Of these, 191 were discovery-focused, examining the relationship between physical activity and built environment; 79 were reviews summarizing previous PABE work; 38 focused on theory and methods for studying PABE; six were delivery-focused, examining PABE interventions; and four addressed other topics.

Conclusions

Network composition suggested PABE is in the discovery phase, although may be transitioning given the large number and central position of review documents that summarize existing literature. The small amount of delivery research was not well integrated into the field. PABE delivery researchers may wish to make explicit connections to the discovery literature in order to better integrate the field.

Keywords: physical activity, built environment, network analysis

Introduction

Ecological approaches to behavioral science and public health have been proposed throughout the last decades and have focused on the interaction between individuals and their physical and socio-cultural context (McLeroy, et al, 1988, Stokols, 1992). More recent work from Sallis et al. has emphasized the inclusion of an additional layer that includes the physical environment in which people live, an important determinant of active and healthy living (Sallis, et al, 2006). Given the rising levels of non-communicable chronic diseases worldwide such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and some types of cancer, attention has turned to investigate relevant and modifiable risk factors including physical inactivity (Eyre, et al, 2008, Thompson, 2003, Knowler, et al, 2002, Laaksonen, et al, 2002, Sallis, et al, 2012).

Factors associated with physical inactivity include global economic transitions, urbanization patterns, and technological changes that create and perpetuate obesogenic physical (built) and social environments (Brownson, et al, 2005, Hill and Peters, 1998). The built environment (e.g., freeways and sidewalks, access to healthy foods and parks) is one of the most commonly cited barriers to physical activity at the population level. Improving opportunities for active lifestyles through built environment is recognized as a promising intervention (Heath, et al, 2006, Wang, et al, 2004) and has been advocated by internationally recognized health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Institute of Medicine, and the World Health Organization (National Research Council Committee on Physical Activity, et al, 2005, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013, Edwards and Tsouros, 2006).

Over the past decade researchers have explored the association between built environment and active lifestyles (Sallis, et al, 2006, Frank, et al, 2003, Owen, et al, 2004, Saelens, et al, 2003, Ferdinand, et al, 2012, Van Holle, et al, 2012). Objective and perceived environment characteristics have been found to be associated with the likelihood of physical activity in high-income countries (Hoehner, et al, 2005, Baker, et al, 2008, Bedimo-Rung, et al, 2005, Roux, et al, 2007, Kramer, et al, 2013). Recent evidence identifying a relationship between physical activity and the built environment has also emerged from low and middle-income countries, suggesting widespread importance (Hallal, et al, 2012, Gomez, et al, 2010, Parra, et al, 2010, Parra, et al, 2011).

This study aims to understand the development and current state of physical activity and built environment (PABE) research to identify gaps and structures that PABE researchers may wish to address or develop as the field continues to evolve. The status and progress of PABE research is tied directly to public health practices and policies and can influence current and future research and practice.

Methods

We applied a citation network approach to understand the development and composition of PABE research from 1986 to 2013. Citation network approaches are useful for characterizing the structure of a research area through examination of the relationships among articles, books, and other documents comprising the field (Hummon and Doreian, 1989).

Data collection

Citation Network Analyzer (CNA), a citation network data collection tool developed in 2007, was designed to efficiently collect an inclusive sample of documents comprising a field of study (Lecy and Moreda, 2011). CNA overcomes bias in traditional literature reviews that identify articles based upon keywords since terminology varies within and across fields. CNA instead builds a network of documents representing a field by identifying seed articles deemed influential in the domain, then capturing a network of documents stemming from these seeds by following citations forward in time (identifying articles that cite the seeds) for a set number of levels (distance from the seed) using a specified sampling rate (percentage of articles collected at each level).

Seed articles were identified by 21 top PABE scholars that were invited to nominate prominent publications in the field. The 21 PABE scholars were active researchers selected on the basis of recognition and prominence in the field. For example, they are commonly keynote speakers at conferences focused on physical activity and built environment topics. To nominate key articles, the scholars were emailed the following: “we are hoping to identify about 10-15 of the earliest key publications in BE & PA research…. [please identify articles] you feel are the top 3 to 5 seminal or key articles on BE & PA research.” Fourteen responded identifying 67 unique articles. From this list we selected the 25 most highly cited articles with the earliest publication dates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Twenty-five seeds used for data collection.

| Title | Type | First Author | Journal | Year | # Cited By |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease | article | Roux | NEJM | 2001 | 850 |

| The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity | article | Kahn | AJPM | 2002 | 771 |

| Travel and the built environment: a synthesis | article | Ewing | Transportation Research Record | 2001 | 688 |

| Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity | article | Sallis | AJPM | 1998 | 618 |

| Travel by design the influence of urban form on travel | book | Boarnet | 2001 | 431 | |

| Impacts of mixed use and density on utilization of three modes of travel: single-occupant vehicle, transit, and walking | article | Frank | Transportation research record | 1994 | 395 |

| Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample | article | Sallis | PM | 1986 | 375 |

| The influence of urban form on travel: an interpretive review | article | Crane | Journal of Planning Literature | 2000 | 348 |

| Predictors of adoption and maintenance of vigorous physical activity in men and women | article | Sallis | PM | 1992 | 288 |

| Assessing perceived physical environmental variables that may influence physical activity | article | Sallis | Research Q for Exercise & Sport | 1997 | 265 |

| Distance between homes and exercise facilities related to frequency of exercise among San Diego residents | article | Sallis | Public Health Reports | 1990 | 238 |

| Physical activity preferences, preferred sources of assistance, and perceived barriers to increased activity among physically inactive Australians | article | Booth | PM | 1997 | 222 |

| Travel choices in pedestrian versus automobile oriented neighborhoods | article | Cervero | Transport Policy | 1996 | 216 |

| Urban form and pedestrian choices: study of Austin neighborhoods | article | Handy | Transportation Research Record | 1996 | 187 |

| Understanding the link between urban form and nonwork travel behavior | article | Handy | J of Planning Educ & Research | 1996 | 186 |

| Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through physical activity: issues and opportunities | article | King | Health Education & Behavior | 1995 | 164 |

| Policy as intervention: environmental and policy approaches to the prevention of cardiovascular disease | article | Schmid | AJPH | 1995 | 132 |

| Geographic information systems and public health: mapping the future | article | Richards | PHR | 1999 | 131 |

| Residential density and travel patterns: review of the literature | article | Steiner | Transportation Research Record | 1994 | 104 |

| Associations of location and perceived environmental attributes with walking in neighborhoods | article | Humpel | AJPH | 2004 | 103 |

| Can the physical environment determine physical activity levels? | article | Ewing | Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews | 2005 | 99 |

| Measuring the determinants of physical activity in the community: current and future directions | article | Baker | Research Q for Exercise & Sport | 2000 | 71 |

| Indicators of activity-friendly communities | article | Ramirez | AJPM | 2006 | 50 |

| Community design and transportation policies | article | Killingsworth | Physician and Sports Medicine | 2001 | 28 |

We collected two levels of data (articles that cite seeds, and articles that cite those articles). We constrained the sample to only include the top 5% of highly cited articles at each level. The 5% rate is justified by research showing constrained snowball samples reduce the size of the database by up to 99% while identifying over 80% of the most highly-cited articles in the literature (Lecy and Beatty, 2012). The resulting network included 2,764 documents including all 67 of the articles initially identified as key to the field by the 14 scholars.

Abstract Coding

Based on abstracts, we coded each document as discovery, delivery, theory and methods, review, other PABE topics, or non-PABE. Following Harris and colleagues (2009), discovery was defined as empirical studies with the purpose of discovery or confirmation of association between built environment and physical activity; delivery was defined as empirical studies of implementation or evaluation of an intervention to increase physical activity through the built environment. Theory and methods documents included development of new theory or methods to study physical activity and the built environment. Review documents summarized previous empirical work on PABE. Documents coded as other were about PABE, but did not fit one of the categories. A document was coded as non if it was not PABE.

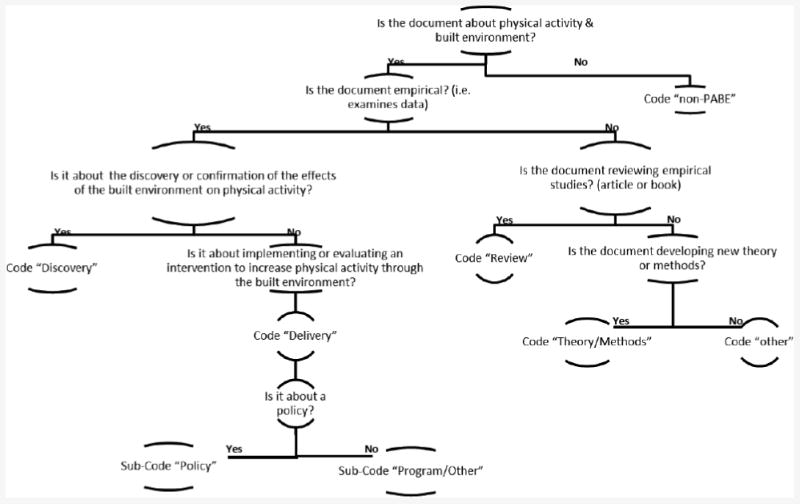

Four coders coded 25 randomly selected abstracts to establish reliability (see Figure 1 for decision rules). The resulting kappa of .83 is considered nearly perfect by Landis and Koch (Landis and Koch, 1977); articles were then divided among coders and coded independently.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for coding articles comprising or connected to the field of physical activity and built environment research.

Analysis

The citation networks were analyzed using (1) descriptive network analysis; and (2) main path analysis.

Descriptive network analysis: key journals, articles, and authors

Descriptive measures were used to identify prominent articles, authors, and journals. Citation networks are directed; links among articles represent the direction of information flow in the network. So, if article B cites article A, the information flows from A to B and is shown A→B in the network. Descriptive network measures included: (1) in-degree: how many articles each article cites in the network, and (2) out-degree: how many times an article was cited within the network.

Main path analysis

The main path is a set of connected articles and the links among them considered the backbone of the network. The main path is identified by calculating traversal weights for all nodes and links in the network. These weights represent the proportion of all paths through the network that contain a specific node or link (De Nooy, et al, 2011), so a traversal weight of .1 would indicate an article is on 10% of the citation paths through the network.

Results

The network included 2,764 unique documents published between 1986 and 2013 and connected by 5,043 citation links. There were 2,511 journal articles (90.8%), 224 books or chapters (8.1%), and 29 documents of other types (1.1%). Because most documents in the network were articles, the term article will be used to represent any document in the network for the remainder of this manuscript.

There were 1,909 unique lead authors contributing an average of 1.4 articles (s.d.=1.3) to the network. Most lead authors (n=1,503) contributed one article. The seven authors contributing 10 or more articles were: James F. Sallis (n=22); Lawrence D. Frank (n=15); Ross C. Brownson (n=11); Bess H. Marcus (n=11); Adam Drewnowski (n=10); Reid Ewing (n=10); Michael D. Marmot (n=10). Those contributing the highest number of PABE articles were: Frank (n=11); Sallis (n=8); Billie Giles-Corti (n=7); Susan L. Handy (n=6); John Pucher (n=6); Brownson (n=5), and Brian E. Saelens (n=5).

There were 617 journals contributing an average of 4.1 articles (s.d.=10.11); 369 journals contributed a single article to the network. The top ten most common journals were: American Journal of Preventive Medicine (AJPM; n=131); Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (n=92); American Journal of Public Health (AJPH; n=87); Preventive Medicine (PM; n=80); Social Science & Medicine (n=56); Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA; n=50); Circulation (n=49); Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (n=38); Annual Review of Public Health (ARPH; n=37); and Pediatrics (n=36).For PABE articles only, the most common journals were AJPM (n=50); PM (n=22); AJPH (n=16); American Journal of Health Promotion (n=13); Health and Place (n=13); Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (n=13); and International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (n=10). Articles in the sample were cited between zero and 7,633 times overall on Google Scholar (median=133). Within the network, each article was cited zero to 322 times. Table 2 shows the top 10 cited articles in the network. Note that three of these were professional publications by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Overall, each article in the network cited between zero and 43 other articles in the network (m=1.8; s.d.=2.6).

Table 2.

Ten most highly cited articles within the citation network.

| First author | Year | Title | Journal | Cited (in Scholar) | Cited (in network) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pate | 1995 | Physical activity and public health: A Recommendation From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine | JAMA | 6388 | 322 |

| Haskell | 2007 | Physical activity and public health. Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association | Circulation | 3443 | 176 |

| Nelson | 2007 | Physical activity and public health in older adults. Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association | Circulation | 1402 | 70 |

| Marmot | 2004 | Status syndrome | Significance | 1388 | 69 |

| Kahn | 2002 | The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity | AJPM | 1230 | 62 |

| French | 2001 | Environmental influences on eating and physical activity | ARPH | 1123 | 56 |

| Cervero | 1997 | Travel demand and the 3Ds: density, diversity, and design | Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment | 1005 | 50 |

| Humpel | 2002 | Environmental factors associated with adults' participation in physical activity: A review | AJPM | 976 | 49 |

| Saelens | 2003 | Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures | Annals of behavioral medicine | 950 | 47 |

| Bandura | 1998 | Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory | Psychology and Health | 875 | 47 |

Many articles in the sample focused solely on physical activity or obesity and related health problems or discussed methods for measuring and analyzing physical activity or obesity and related issues (n=2,446; 88.5%). However, 318 articles focused specifically on PABE. Of these, 191 (60.1%) were discovery-focused; 79 (24.8%) were review; 38 (11.9%) were theory and methods; six (1.9%) were delivery-focused examining policies (n=5) or programs (n=1); and four addressed other PABE topics.

Citation patterns (Table 3) revealed 70.8% of citations in the network were citing non-PABE articles. With 88.5% of articles in the network identified as non-PABE, this indicates that a disproportionate number of ties in the network are going to the small proportion of articles that focus on PABE (29.2%). Specifically, PABE review articles were cited 479 times (9.5% of citations), but comprise just 2.9% of the network; PABE discovery articles were cited 776 times (15.4%), but comprise 6.9% of the network. No articles in the network cited the six delivery articles, although these articles had an average of 83.7 citations on Google Scholar and were published as early as 2004. The delivery articles cited 11 network members, seven non, three discovery, and one review.

Table 3.

Patterns of citation links by article type in the citation network examining the field of physical activity and built environment.

| Cited | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Non | Delivery | Discovery | Other | Review | Theory | Total | ||

| Cited by | |||||||||

| Non | 2446 | 2836 | 7 | 257 | 5 | 167 | 69 | 3341 | |

| Delivery | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Discovery | 191 | 350 | 3 | 311 | 2 | 189 | 64 | 919 | |

| Other | 4 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 | |

| Review | 79 | 144 | 1 | 298 | 2 | 87 | 51 | 583 | |

| Theory | 38 | 60 | 0 | 64 | 1 | 35 | 11 | 171 | |

| Total | 2764 | 3572 | 11 | 776 | 10 | 479 | 195 | 5043 | |

Main path analysis

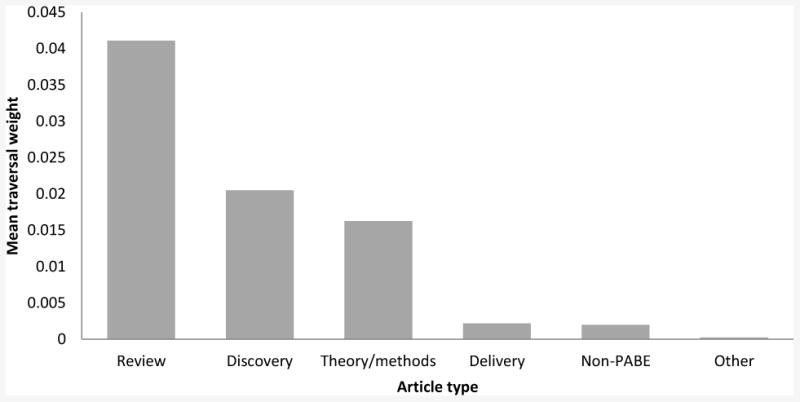

To identify the key articles in the development of this research area, we calculated the traversal weight for each article in the network. Based on patterns in the descriptive network analysis, we hypothesized that (1) PABE articles would have significantly higher average traversal weight than non-PABE articles, (2) review articles would have significantly higher average traversal weight than other types of articles in the network, and (3) delivery articles would have significantly lower traversal weights than all other types of articles in the network. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) identified a significant difference in the mean traversal weight across the six types of articles (F(5,2758)=36.0; p<.001). Planned comparisons testing the three hypotheses found that: (1) PABE articles do have significantly higher average traversal weights than non-PABE articles (t=3.7; p<.001); review articles have significantly higher average traversal weights than other article types (t=4.4; p<.001); and delivery articles have significantly lower traversal weights than other article types (t=4.8; p<.001). Figure 2 shows the average traversal weights for the six article types.

Figure 2.

Average transversal weights by article type in the citation network.

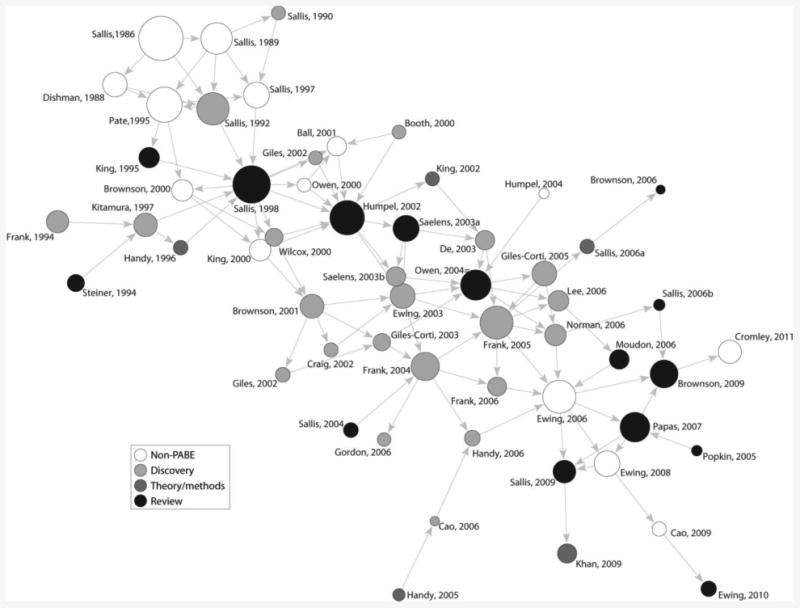

The main path, which is the set of connected articles with the highest traversal weights, included 57 articles by 28 first authors in 28 journals and 4 books between 1986 and 2011. The path was comprised of 40.4% discovery articles, 26.3% reviews, 8.8% theory and methods, and 24.6% non-PABE articles. No delivery or other PABE topic articles were in the main path.

The main path included nine of the 25 seeds and articles from both search levels. On average, main path articles were cited 24.9 times (s.d.=41.7), which is significantly higher than the 1.8 times (s.d.=9.2) articles in the overall network were cited (t=4.3; p < .001). AJPM contributed 10 main path articles (17.5%), while Preventive Medicine contributed six (10.5%) articles; no other journal contributed more than four articles to the main path. Sallis contributed the most main path articles (17.5%), while Brownson, Ewing, Frank, and Giles-Corti each contributed four (7.0%). Figure 2 shows the main path with nodes sized by traversal weight and color showing article type. A list of main path articles is included as Appendix A.

Discussion

In the 1990s physical activity researchers turned to the built environment as a key facilitator of, and barrier to, physical activity. Early built environment studies focused on the convenience of recreation facilities and progressed to focus on transportation, city planning, and land use (Sallis, 2009). While there have been reviews conducted summarizing trends and findings across the last 20 years of PABE research, this is the first to map citation patterns demonstrating development of the field. We found that PABE review articles were most prominent across the network by virtue of being the most highly cited and having significantly higher traversal weights than other types of articles. The high traversal weights show that these reviews are key in holding the network together. Discovery-focused articles were also prominent, second only to reviews in terms of being highly cited and having high traversal weights. Delivery articles were scarce (n=6) and were not cited within the network. These findings suggest three important features of current PABE research that may aid in strategic planning for the field: (1) The composition of the network suggests PABE research is still largely in the discovery phase, although may be transitioning given the prominent network location of review documents; (2) the small amount of delivery research that currently exists is not well integrated into the field; and (3) summary documents, such as guidelines and systematic reviews, are occupying prominent positions in this network of research.

The progression from scientific discovery to delivery of interventions is fundamental in public health (Harris, et al, 2009). Not surprisingly given its youth, a majority of PABE articles were discovery-focused with only a few delivery-focused studies connected to the field at the time of data collection. The structure of the main path suggests early PABE and related research took place beginning in the late-1980s and early 1990s and was synthesized by several review articles in the early 2000s. This first 10-15 years of PABE work was then followed by a second generation of discovery articles in the early 2000s and subsequent reviews in the late 2000s. While only six articles in the network fit the operational definition of delivery, it may be worth noting that none of these articles were connected to the main path. The exclusion from the main path may be explained by a lack of connection between discovery and delivery research, a pattern also seen in secondhand smoke research (Harris, et al, 2009). In the case of the PABE network, there were no articles in the network citing the delivery studies, even though half were published five years or more prior to data collection. The six delivery studies (Buehler and Pucher, 2011, Buehler and Pucher, 2012, Giles-Corti, et al, 2008, Pucher, et al, 2011, Schwanen, et al, 2004, Economos, et al, 2007) cited an average of 1.8 articles in the network (Table 3). Connections between discovery and delivery research can aid in ensuring that public health researchers and practitioners doing delivery work are incorporating existing evidence about relationships between physical activity and built environment. Likewise, discovery researchers can build on delivery research to focus on new areas of discovery and continue to grow the field.

As this number of delivery studies grows, delivery researchers and practitioners who seek to apply findings in real world settings are likely to benefit from the growing field of dissemination and implementation science (Brownson, et al, 2012). Research from this field has provided key lessons: 1) dissemination generally does not occur spontaneously and naturally (Glasgow, et al, 2004b), 2) passive dissemination approaches are largely ineffective (Bero, et al, 1998, Lehoux, et al, 2005), 3) single-source prevention messages are generally less effective than comprehensive approaches (Richard, et al, 2011, Zaza, et al, 2005), 4) stakeholder involvement in the research or evaluation process is likely to enhance dissemination (Green, 2008, Greene, 1987, Glasgow, et al, 2004a, Mendel, et al, 2008, Wandersman, et al, 2008, Minkler and Salvatore, 2012), 5) theory and frameworks for dissemination are beneficial (Tabak, et al, 2012, Wilson, et al, 2010), and 6) the process of dissemination should to be tailored to specific audiences (Lomas, 2006).

Many of the highly cited documents in the network and in the main path were scientific review articles and guidelines about physical activity behavior and interventions. This focus on summary documents is not unique to PABE research; a citation network analysis of secondhand smoke research found the Surgeon General Reports, Environmental Protection Agency guidelines, and other summary documents were cited by both delivery and discovery researchers, filling a gap between the two (Harris, et al, 2009). While summary documents are useful for quickly understanding an area, they take time to compile and sometimes do not include the most recent research, which can limit progress in a field.

Limitations to this study include data collection. First, CNA moves forward in time to collect the sample of articles; because the earliest seed article was from 1986, earlier research is not included. The sampling technique is designed to identify a representative, not exhaustive, sample; it is possible that some relevant articles were missed. Finally, the sample includes non-PABE research. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to examine the structure of PABE research development.

Conclusions

As PABE research progresses into the delivery phase, we have three primary recommendations for researchers working in this area: (1) look beyond summary documents to find the most current evidence on which to build from, (2) actively seek out, and make explicit connections with, existing evidence from discovery-focused articles, and (3) broaden research agendas to include dissemination and implementation research of discovery-related interventions.

Figure 3.

The main path of articles forming the field of physical activity and built environment research.

Highlights.

We examined the development of research on physical activity and the built environment

Citation network analysis provided insight into the composition and structure of the field

The network demonstrated that physical activity and built environment research is currently focused on discovery work to understand relationships between physical activity and the built environment

Few studies on physical activity and built environment have evaluated interventions

New connections between intervention research and discovery research may strengthen the field

Appendix A: Articles in the Main Path

- Ball K, Bauman A, Leslie E, Owen N. Perceived environmental aesthetics and convenience and company are associated with walking for exercise among Australian adults. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(5):434–440. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth ML, Owen N, Bauman A, Clavisi O, Leslie E. Social-cognitive and perceived environment influences associated with physical activity in older Australians. Prev Med. 2000;31(1):15–22. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Baker EA, Housemann RA, Brennan LK, Bacak SJ. Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1995–2003. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Eyler AA, King AC, Brown DR, Shyu YL, Sallis JF. Patterns and correlates of physical activity among US women 40 years and older. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):264–270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: a review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:341–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(4 Suppl):S99. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Handy SL, Mokhtarian PL. The influences of the built environment and residential self-selection on pedestrian behavior: evidence from Austin, TX. Transportation. 2006;33(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Mokhtarian PL, Handy SL. Examining the impacts of residential self-selection on travel behaviour: a focus on empirical findings. Transport Reviews. 2009;29(3):359–395. [Google Scholar]

- Craig CL, Brownson RC, Cragg SE, Dunn AL. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity: a study examining walking to work. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(2):36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromley EK, McLafferty SL. GIS and public health. Guilford Publication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Environmental correlates of physical activity in a sample of Belgian adults. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;18(1):83–92. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK. Exercise adherence: Its impact on public health. Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Brownson RC, Berrigan D. Relationship between urban sprawl and weight of United States youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(6):464–474. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Cervero R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association. 2010;76(3):265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Schmid T, Killingsworth R, Zlot A, Raudenbush S. Relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;18(1):47–57. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing RH, Anderson G. Growing cooler: the evidence on urban development and climate change. ULI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Andresen MA, Schmid TL. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Pivo G. Impacts of mixed use and density on utilization of three modes of travel: single-occupant vehicle, transit, and walking. Transportation research record. 1994:44–44. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Chapman JE, Saelens BE, Bachman W. Many pathways from land use to health: associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. Journal of the American Planning Association. 2006;72(1):75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Schmid TL, Sallis JF, Chapman J, Saelens BE. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: findings from SMARTRAQ. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(2):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, Broomhall MH, Knuiman M, Collins C, Douglas K, Ng K, Donovan RJ. Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(2 Suppl 2):169. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine. 2002a;54(12):1793–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Socioeconomic status differences in recreational physical activity levels and real and perceived access to a supportive physical environment. Preventive Medicine. 2002b;35(6):601–611. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Relative influences of individual, social environmental, and physical environmental correlates of walking. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9) doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy S. Critical assessment of the literature on the relationships among transportation, land use, and physical activity Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California, Davis. Prepared for the Committee on Physical Activity, Health, Transportation, and Land Use. Washington: Transportation Research Board; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Handy S, Cao X, Mokhtarian PL. Self-selection in the relationship between the built environment and walking: Empirical evidence from Northern California. Journal of the American Planning Association. 2006;72(1):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Handy SL. Understanding the link between urban form and nonwork travel behavior. Journal of planning education and research. 1996;15(3):183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Iverson D, Owen N, Leslie E, Bauman A. Perceived environment attributes, residential location and walking for particular purposes. Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences-Papers. 2004:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults' participation in physical activity. American journal of preventive medicine. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Kakietek J, Zaro S. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. US Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of US middle-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychology. 2000;19(4):354–364. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Jeffery RW, Fridinger F, Dusenbury L, Provence S, Hedlund SA, Spangler K. Environmental and policy approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention through physical activity: issues and opportunities. Health Education & Behavior. 1995;22(4):499–511. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Stokols D, Talen E, Brassington GS, Killingsworth R. Theoretical approaches to the promotion of physical activity: forging a transdisciplinary paradigm. American journal of preventive medicine. 2002;23(2):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura R, Mokhtarian PL, Laidet L. A micro-analysis of land use and travel in five neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area. Transportation. 1997;24(2):125–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Moudon AV. Correlates of walking for transportation or recreation purposes. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3:S77. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Lee C, Cheadle AD, Garvin C, Johnson D, Schmid TL, Lin L. Operational definitions of walkable neighborhood: theoretical and empirical insights. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3:S99. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Nutter SK, Ryan S, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Patrick K. Community design and access to recreational facilities as correlates of adolescent physical activity and body-mass index. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3:S118. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Leslie E, Salmon J, Fotheringham MJ. Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2000;28(4):153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29(1):129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Wilmore JH. Physical activity and public health. JAMA. 1995;273(5):402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Duffey K, Gordon-Larsen P. Environmental influences on food choice, physical activity and energy balance. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;86(5):603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93(9):1552–1558. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003b;25(2):80–91. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006a;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Kraft MK. Active transportation and physical activity: opportunities for collaboration on transportation and public health research. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2004;38(4):249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. The role of built environments in physical activity, eating, and obesity in childhood. The Future of Children. 2006b;16(1):89–108. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP, Vranizan KM, Taylor CB, Solomon DS. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Preventive Medicine. 1986;15(4):331–341. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, Elder JP, Hackley M, Caspersen CJ, Powell KE. Distance between homes and exercise facilities related to frequency of exercise among San Diego residents. Public Health Reports. 1990;105(2):179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of vigorous physical activity in men and women. Preventive Medicine. 199;21(2):237–251. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90022-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Johnson MF, Calfas KJ, Caparosa S, Nichols JF. Assessing perceived physical environmental variables that may influence physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1997;68(4):345–351. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Hofstetter CR, Faucher P, Elder JP, Blanchard J, Caspersen CJ, Christenson GM. A multivariate study of determinants of vigorous exercise in a community sample. Preventive Medicine. 1989;18(1):20–34. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15(4):379–397. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner RL. Residential density and travel patterns: review of the literature. Transportation Research Record. 1994;1466 [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Castro C, King AC, Housemann R, Brownson RC. Determinants of leisure time physical activity in rural compared with urban older and ethnically diverse women in the United States. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54(9):667–672. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.9.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baker E, Schootman M, Kelly C, Barnidge E. Do recreational resources contribute to physical activity? Journal of physical activity & health. 2008;5:252. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedimo-Rung AL, Mowen AJ, Cohen DA. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: a conceptual model. AmJPrevMed. 2005;28:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317:465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Boehmer TK, Luke DA. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? AnnuRevPublic Health. 2005;26:421–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler R, Pucher J. Cycling to work in 90 large American cities: new evidence on the role of bike paths and lanes. Transportation. 2012;39:409–432. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler R, Pucher J. Sustainable transport in Freiburg: lessons from Germany's environmental capital. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 2011;5:43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity and built environment: communities putting prevention to work (CPPW) 2013 2013 [Google Scholar]

- De Nooy W, Mrvar A, Batagelj V. Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Economos C, Hyatt R, Goldberg J, Must A, Naumova E, Collins J, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity. 2007;15:1325. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P, Tsouros A. Promoting physical activity and active living in urban environments: the role of local governments, the solid facts. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre H, Kahn R, Robertson RM, Clark NG, Doyle C, Gansler T, et al. Preventing Cancer, Cardiovascular Disease, and Diabetes: A Common Agenda for the American Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2008;54:190–207. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Engelke P, Schmid T. Health and community design: The impact of the built environment on physical activity. Island Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, Knuiman M, Timperio A, Van Niel K, Pikora TJ, Bull FCL, et al. Evaluation of the implementation of a state government community design policy aimed at increasing local walking: design issues and baseline results from RESIDE, Perth Western Australia. Prev Med. 2008;46:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Goldstein MG, Ockene JK, Pronk NP. Translating what we have learned into practice. Principles and hypotheses for interventions addressing multiple behaviors in primary care. AmJPrevMed. 2004a;27 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Marcus AC, Bull SS, Wilson KM. Disseminating effective cancer screening interventions. Cancer. 2004b;101:1239–1250. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LF, Sarmiento OL, Parra DC, Schmid TL, Pratt M, Jacoby E, et al. Characteristics of the built environment associated with leisure-time physical activity among adults in Bogota, Colombia: A Multilevel Study. Journal of physical activity & health. 2010;7:196. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? FamPract. 2008;25:i20–i24. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JC. Stakeholder participation in evaluation design: Is it worth the effort? EvalProgram Plann. 1987;10:379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. The Lancet. 2012;380:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JK, Luke DA, Zuckerman RB, Shelton SC. Forty years of secondhand smoke research: the gap between discovery and delivery. AmJPrevMed. 2009;36:538–548. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath GW, Brownson RC, Kruger J, Miles R, Powell KE, Ramsey LT. The Effectiveness of Urban Design and Land Use and Transport Policies and Practices to Increase Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3:S55–S76. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science. 1998;280:1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehner CM, Brennan Ramirez LK, Elliott MB, Handy SL, Brownson RC. Perceived and objective environmental measures and physical activity among urban adults. AmJPrevMed. 2005;28:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummon N, Doreian P. Connectivity in a citation network - the development of DNA theory. Social networks. 1989;11:39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D, Maas J, Wingen M, Kunst AE, Nelson R, Horowitz J, et al. Neighbourhood safety and leisure-time physical activity among Dutch adults: a multilevel perspective. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2013;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, Salonen JT, Niskanen LK, Rauramaa R, Lakka TA. Low levels of leisure-time physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness predict development of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1612–1618. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecy J, Moreda D. cna: Citation Network Analyzer R package version 0.2.0 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Lecy JD, Beatty KE. Representative Literature Reviews Using Constrained Snowball Sampling and Citation Network Analysis 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux P, Denis JL, Tailliez S, Hivon M. Dissemination of health technology assessments: identifying the visions guiding an evolving policy innovation in Canada. JHealth PolitPolicy Law. 2005;30:603–642. doi: 10.1215/03616878-30-4-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: who should do what? AnnNYAcadSci. 2006;703:226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:21–37. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Salvatore AL. 10 Participatory Approaches for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. 2012;192 [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US). Committee on Physical Activity, Land Use, Institute of Medicine (US) Does the Built Environment Influence Physical Activity?: Examining The Evidence. Transportation Research Board National Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand A, Sen B, Rahurkar S, Engler S, Menachemi N. The relationship between built environments and physical activity: a systematic review. AmJPublic Health. 2012;102:e7–e13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking. AmJPrevMed. 2004;27:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra DC, Gomez LF, Sarmiento OL, Buchner D, Brownson R, Schimd T, et al. Perceived and objective neighborhood environment attributes and health related quality of life among the elderly in Bogotá, Colombia. SocSciMed. 2010;70:1070–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra DC, Hoehner CM, Hallal PC, Ribeiro IC, Reis R, Brownson RC, et al. Perceived environmental correlates of physical activity for leisure and transportation in Curitiba. BrazilPrevMed. 2011;52:234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucher J, Buehler R, Seinen M. Bicycling renaissance in North America? An update and re-appraisal of cycling trends and policies. Transportation research part A: policy and practice. 2011;45:451–475. [Google Scholar]

- Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. AnnuRevPublic Health. 2011;32 doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AVD, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, Brown DG, Moore L, Brines S, et al. Availability of recreational resources and physical activity in adults. AmJPublic Health. 2007;97 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. AmJPublic Health. 2003;93 doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF. Measuring physical activity environments: a brief history. AmJPrevMed. 2009;36:S86–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Floyd MF, Rodrguez DA, Saelens BE. Recent Advances in Preventive Cardiology and Lifestyle Medicine. Circulation. 2012;125:729–737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. AnnuRevPublic Health. 2006;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen T, Dijst M, Dieleman FM. Policies for urban form and their impact on travel: the Netherlands experience. Urban Stud. 2004;41:579–603. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. AmPsychol. 1992;47:6–22. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. AmJPrevMed. 2012;43:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PD. Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol. 2003;23:1319–1321. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000087143.33998.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Holle V, Deforche B, Van Cauwenberg J, Goubert L, Maes L, Van de Weghe N, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and different domains of physical activity in European adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:807. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. AmJCommunity Psychol. 2008;41:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Macera CA, Scudder-Soucie B, Schmid T, Pratt M, Buchner D, et al. Cost analysis of the built environment: the case of bike and pedestrian trials in Lincoln, Neb. AmJPublic Health. 2004;94:549. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I. Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks. Implementation Science. 2010;5:91. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW. The guide to community preventive services: What works to promote health? Oxford University Press; USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]