Abstract

We demonstrate CRISPR-Cas9–mediated correction of a Fah mutation in hepatocytes in a mouse model of the human disease hereditary tyrosinemia. Delivery of components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system by hydrodynamic injection resulted in initial expression of the wild-type Fah protein in ~1/250 liver cells. Expansion of Fah-positive hepatocytes rescued the body weight loss phenotype. Our study indicates that CRISPR-Cas9–mediated genome editing is possible in adult animals and has potential for correction of human genetic diseases.

The type II bacterial clustered, regularly interspaced, palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated (Cas) system has been engineered into a powerful genome editing tool consisting of the Cas9 nuclease and a single guide RNA (sgRNA)1–4. The sgRNA targets Cas9 to genomic regions that are complementary to the 20-nucleotide (nt) target region of the sgRNA and that contain a 5′-NGG-3′ protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM). Double-stranded DNA breaks generated by Cas9 at target loci are repaired by nonhomologous end-joining or homology-directed repair (HDR). CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has been applied to correct disease-causing mutations in mouse zygotes and human cell lines for cataract5 and cystic fibrosis6, but delivery to adult mammalian organs to correct genetic disease genes has not been reported to our knowledge.

To investigate the potential of CRISPR-Cas9–mediated in vivo genome editing in adult animals, we used a mouse model of hereditary tyrosinemia type I (HTI), a fatal genetic disease caused by mutation of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH), the last enzyme in the tyrosine catabolic pathway (Supplementary Fig. 1a)7,8. The Fah5981SB mouse model8,9 (referred to here as Fahmut/mut) of HTI harbors the same homozygous G→A point mutation of the last nucleotide of exon 8 as causes the human disease. This mutation causes skipping of exon 8 during splicing and formation of truncated, unstable FAH protein (Fig. 1a). FAH deficiency causes accumulation of toxic metabolites, such as fumarylacetoacetate, in hepatocytes, resulting in severe liver damage8. 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC), a pharmacological inhibitor of the tyrosine catabolic pathway upstream of FAH, rescues the phenotype and prevents acute liver injury8. A previous study showed that targeted integration by homologous recombination of adeno-associated virus carrying the wild-type Fah sequence could achieve stable gene repair in vivo in mice, but required multiple rounds of NTBC withdrawal and recovery8. Liver cells in which Fah has been repaired have a selective advantage and can expand and repopulate the liver8. Diseases in which positive selection of corrected cells occurs8,9 may be particularly suitable for gene repair–based therapy; indeed, repair of 1/10,000 hepatocytes was reported to rescue the phenotype of Fahmut/mut mice8.

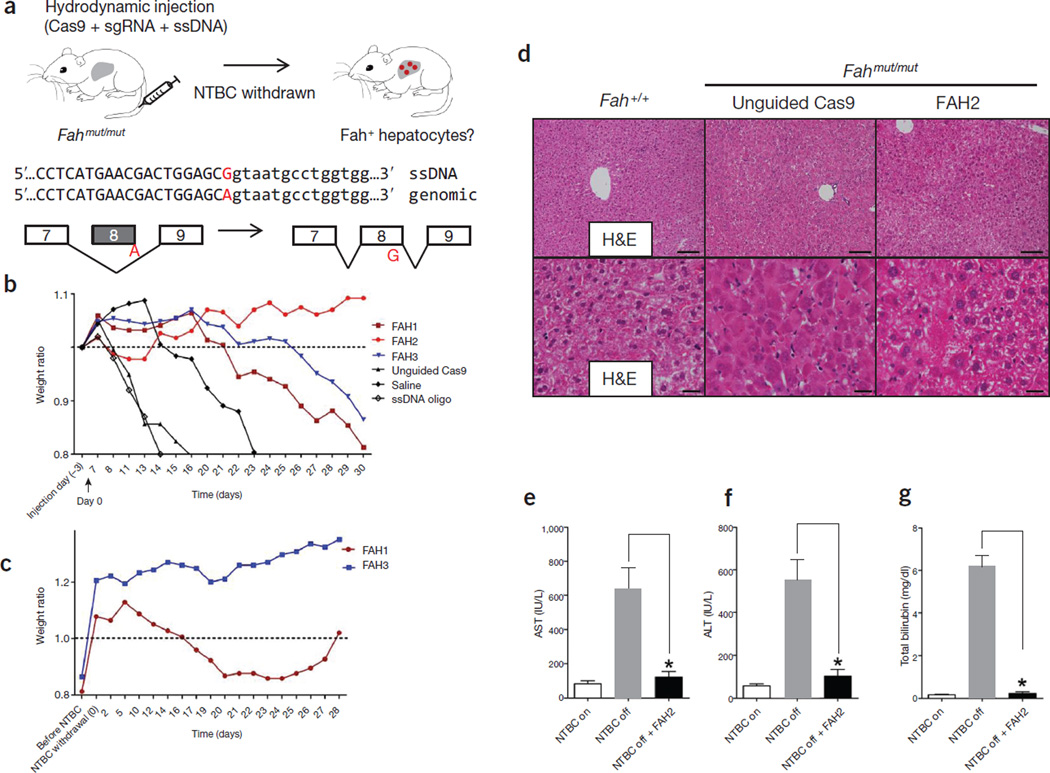

Figure 1.

Hydrodynamic injection of CRISPR components rescues lethal phenotype of Fah-deficient mice. (a) Experimental design. Fahmut/mut mice harbor a homozygous G→A point mutation at the last nucleotide of exon 8 (red), causing skipping of exon 8 during splicing. pX330 plasmids expressing Cas9 and a sgRNA targeting the Fah locus are delivered to the liver by hydrodynamic tail vein injection. A ssDNA oligo with the correct fragment of Fah sequence (i.e., the G allele) is co-injected to serve as a donor template to repair the ‘A’ mutation. Exon and intron sequences are in upper and lower cases, respectively. (b) Fahmut/mut mice were injected with saline only, ssDNA oligo only, ssDNA oligo plus pX330 (unguided Cas9), or ssDNA oligo plus pX330 expressing Cas9 and one of the three Fah sgRNAs (FAH1, FAH2 and FAH3). Body weight was monitored over time and normalized to pre-injection weight. Arrow indicates withdrawal of NTBC water (defined as day 0, which is 3 d after injection). (c) Mice injected with FAH1 or FAH3 in b were put back on NTBC water for 7 d and then again withdrawn from NTBC for 28 d. (d) H&E staining of liver sections from wild-type (Fah+/+) or Fahmut/mut mice injected with unguided Cas9 or Cas9 with the FAH2 sgRNA and kept off NTBC water. The FAH2 sample is from a mouse 30 d after NTBC withdrawal. Scale bars, 100 µm for upper panels, 20 µm for lower panels. (e–g) Liver damage markers (aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and bilirubin) were measured in peripheral blood from Fahmut/mut mice injected with saline or ssDNA oligo only or unguided Cas9 (NTBC off) or FAH2 (NTBC off + FAH2, day 30). Fahmut/mut mice on NTBC water (NTBC on) served as a control. * P < 0.01 (n = 3 mice) using one-way ANOVA. Error bars, mean ± s.e.m.

To edit the endogenous Fah locus, we individually cloned three sgRNAs targeting Fah (FAH1, FAH2 and FAH3) (Supplementary Methods) into the pX330 vector2, which co-expresses one sgRNA and Cas9 (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). To facilitate homologous recombination and correct the G→A splicing mutation, a 199-nt, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donor was synthesized harboring the wild-type G nucleotide and homology arms flanking the sgRNA target region (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Adult Fahmut/mut mice were given hydrodynamic tail vein injections10 with (i) saline, (ii) the ssDNA oligo alone, (iii) ssDNA oligo plus pX330 expressing Cas9 only (‘unguided Cas9’) or (iv) ssDNA oligo plus pX330 expressing Cas9 and one of the sgRNAs (FAH1–3). Fahmut/mut mice injected with saline, ssDNA oligo alone or unguided Cas9, and kept without NTBC-containing water, rapidly lost 20% of their body weight and had to be euthanized (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Mice receiving oligo plus pX330 expressing Cas9 plus FAH2 did not lose weight, and weight loss in FAH1- and FAH3-treated mice was <20% after 30 d without NTBC water. Mice treated with FAH1 or FAH3 were put back on NTBC water for 7 d and subjected to a second round of NTBC withdrawal for 28 d; these mice regained all the weight they had lost (Fig. 1c). Liver damage was substantially less in FAH2-treated mice at 30 d off NTBC water compared to untreated Fahmut/mut mice that were not receiving NTBC water, as indicated by liver histology (Fig. 1d) and serum markers such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and billirubin8 (Fig. 1e–g), suggesting a functional rescue of the Fah deficiency– induced liver damage.

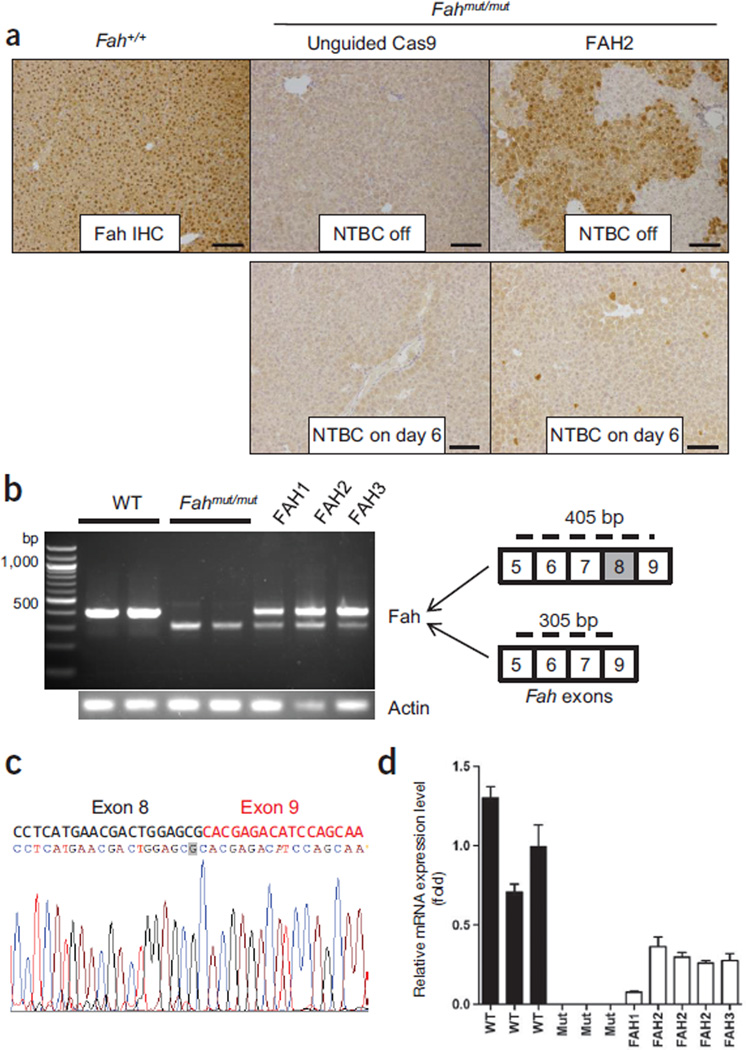

To see whether Cas9-mediated genome editing generates Fah+ hepatocytes in vivo, we examined the liver tissue of treated mice by immunohistochemical staining with an Fah-specific antibody. Thirty-three days after treatment with FAH2 and 30 d without NTBC water, sites Fahmut/mut mice had widespread patches of Fah+ hepatocytes (33.5% ± 3.3%, n = 3 mice) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). To measure the initial Fah gene repair frequency, we treated Fahmut/mut mice with FAH2 and kept them on NTBC water (to prevent positive selection of corrected cells) for 6 d before euthanizing them. As shown by immunohistochemical staining of Fah+ cells, the initial repair frequency was 0.40 ± 0.12% (n = 3 mice) for mice treated with FAH2 compared to 0.01 ± 0.02% for those with unguided Cas9 (Fig. 2a). We also performed deep sequencing to examine the initial repair rate; however, due to the error rate of sequencing, the mixture of nonparenchymal cells and polyploidy of hepatocytes, this approach could not detect low-frequency single-nucleotide polymorphisms in hepatocytes11.

Figure 2.

CRISPR-Cas9–mediated editing corrects Fah splicing mutation in the liver. (a) Fah immunohistochemistry (IHC) of Fahmut/mut mice injected with unguided Cas9 or Cas9 plus the FAH2 sgRNA. Upper panel: FAH2 mice were off NTBC water for 30 d as in Figure 1d. There are 33.5% ± 3.3% Fah+ cells (n = 3 mice). Lower panel: mice were kept on NTBC water and euthanized at day 6 to estimate initial repair rate. Fah+ cell counts were 0.40 ± 0.12% for FAH2 and 0.01 ± 0.02% for unguided Cas9. P < 0.01 (n = 3 mice) using an unpaired t-test. Fah+/+ mice are shown as a control. Scale bars, 100 µm. (b) RT-PCR in liver RNA from wild-type (Fah+/+), Fahmut/mut and Fahmut/mut mice injected with FAH1, 2 or 3, using primers spanning exons 5–9 to amplify wild-type Fah (405 bp) and mutant Fah (305 bp, lacking exon 8). FAH-treated mice were harvested at the endpoints of NTBC withdrawal. (c) Representative sequence of the 405-bp bands in FAH2-treated mice. The corrected G nucleotide is highlighted in gray. (d) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of wild-type Fah mRNA expression using primers spanning exons 8 and 9. Error bars, s.d. from three technical replicates for each individual mouse.

We also carried out RT-PCR using primers spanning Fah exons 5–9 to determine whether the Fah splicing mutation was corrected in the liver. We found that wild-type mice had a 405-bp PCR band containing exon 8, Fahmut/mut mice had a 305-bp PCR band corresponding to the truncated Fah mRNA lacking exon 8 and Fahmut/mut mice injected with FAH1, 2 or 3 had both the 305- and 405-bp PCR bands, indicating that the exon 8 to exon 9 splicing is restored in a subset of hepatocytes (Fig. 2b). Sequencing of the 405-bp bands in CRISPR-Cas9 treated mice confirmed that the corrected G nucleotide is included in the PCR product (Fig. 2c). Quantitative RT-PCR using primers spanning exons 8 to 9 on liver samples from CRISPR-Cas9–treated mice showed they had Fah mRNA at 8–36% of levels in wild-type mice at the end of NTBC water withdrawal (Fig. 2d). These levels are consistent with the proportion of Fah+ hepatocytes detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a) and the A→G correction rate (~9%, n = 2) detected by deep sequencing in FAH2-treated livers at 30 d off NTBC (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Table 3). We note that an indel rate of ~26% was also detected by sequencing of these samples (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Table 3); further work will be needed to assess the initial rate of indel formation compared to gene correction.

To examine potential off-target effects, we used a published prediction tool2 to identify potential off-target sites in the mouse genome for FAH1, 2 and 3 (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). In mouse 3T3 cells transfected with FAH 1, 2, 3 or control (unguided Cas9), the editing at the Fah locus and three or four potential off-target sites was measured using the mismatch-specific Surveyor nuclease assay1. Cleavage was detected at Fah in 3T3 cells, indicating that the one nucleotide mismatch between FAH1, 2 and 3 and the wild-type Fah gene does not prevent Cas9-mediated editing (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). Cleavage was not detected at the assayed three to four top-ranking off-target sites for each sgRNA (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). The PCR products from three off-target sites of FAH2 were sequenced, and <0.3% indels were detected (Supplementary Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 4). Wildtype FVB mice injected with Cas9 plus sgRNA showed no body weight loss, no signs of hyperplasia and extremely low Cas9 expression after 3 months (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8), suggesting that hydrodynamic injection of these components was well-tolerated.

In summary, these data demonstrate the potential to correct disease genes in vivo in adult mouse liver using a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Transient expression of Cas9, sgRNA and a co-injected ssDNA by non-viral hydrodynamic injection is sufficient to restore the weight loss of a mouse model of HTI. The strong positive selection and expansion of Fah+ hepatocytes in the Fahmut/mut liver may have contributed to the correction of the disease phenotype8, given the observed initial genetic correction rate of ~1/250 cells. We note that the initial efficiency of repair using zinc finger nucleases was also low and was substantially improved by subsequent work to correct hemophilia in mice12. We also note that hydrodynamic injection is unlikely to be used for clinical implementation. Therefore, improvements to CRISPR delivery methods and repair efficiency will be required for its broad therapeutic application (Supplementary Discussion), in particular to increase the rate of gene correction and to target other tissues. Further studies will be required to evaluate the extent of off-target effects13, particularly in vivo, and strategies to reduce off-target effects (such as Cas9 nickases14) may help. This proof-of-principle study indicates that correction of genetic disease in vivo with CRISPR-Cas9 may be possible, and we believe that recent advances in the delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics provide hope that CRISPR-Cas9–mediated correction may be translatable to humans15.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank I. Zhuang and W. Cai for technical assistance, F. Zhang for sharing pX330 CRISPR vectors, and D. Crowley and K. Cormier for histology. This work was supported in part by grants 2-PO1-CA42063 to P.A.S. and T.J. and core grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01-CA133404 and the Marie-D. & Pierre Casimir-Lambert Fund to P.A.S. T.J. is a Howard Hughes Investigator, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and a Daniel K. Ludwig Scholar. H.Y. and S.C. are supported by 5-U54-CA151884-04 NIH Centers for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence and the Harvard-MIT Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence. W.X. is supported by grant 1K99CA169512. S.C. is a Damon Runyon Fellow (DRG-2117-12). The authors acknowledge the service of the late Sean Collier to the MIT community. We thank the Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support.

Footnotes

Accession codes. BioProject: PRJNA242331.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.Y., W.X. and D.G.A. designed the study. H.Y., W.X., S.C., R.L.B. and E.B. performed experiments and analyzed data. M.G., V.K. and P.A.S. provided reagents and conceptual advice. H.Y., W.X., T.J. and D.G.A. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Cong L, et al. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu PD, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mali P, et al. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Y, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwank G, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azuma H, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:903–910. doi: 10.1038/nbt1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulk NK, et al. Hepatology. 2010;51:1200–1208. doi: 10.1002/hep.23481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aponte JL, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:641–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu F, Song Y, Liu D. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen R, Korneliussen T, Albrechtsen A, Li Y, Wang J. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, et al. Nature. 2011;475:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature10177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Y, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran FA, et al. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanasty R, Dorkin JR, Vegas A, Anderson D. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:967–977. doi: 10.1038/nmat3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.