Abstract

Although RSV causes serious pediatric respiratory disease, an effective vaccine does not exist. To capture the strengths of a live virus vaccine, we have used the murine parainfluenza virus type 1 (Sendai virus [SV]) as a xenogeneic vector to deliver the G glycoprotein of RSV. It was previously shown (J. L. Hurwitz, K. F. Soike, M. Y. Sangster, A. Portner, R. E. Sealy, D. H. Dawson, and C. Coleclough, Vaccine 15:533-540, 1997) that intranasal SV protected African green monkeys from challenge with the related human parainfluenza virus type 1 (hPIV1), and SV has advanced to clinical trials as a vaccine for hPIV1 (K. S. Slobod, J. L. Shenep, J. Lujan-Zilbermann, K. Allison, B. Brown, R. A. Scroggs, A. Portner, C. Coleclough, and J. L. Hurwitz, Vaccine, in press). Recombinant SV expressing RSV G glycoprotein was prepared by using reverse genetics, and intranasal inoculation of cotton rats elicited RSV-specific antibody and elicited protection from RSV challenge. RSV G-recombinant SV is thus a promising live virus vaccine candidate for RSV.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is among the most important causes of serious respiratory disease among young children (18). RSV was estimated to be responsible for >90,000 hospitalizations in 1989 (1) and for costing approximately $300 million/year in the United States (6). Despite this epidemiologic importance, an effective vaccine is not available.

The best known RSV vaccine was a formalin-inactivated (FI) vaccine tested in the 1960s. This vaccine failed to protect and resulted in enhanced disease upon natural infection (5), likely due to aberrant T-cell priming without effective neutralizing antibody priming (3, 14). Results of the FI-RSV vaccine contrast with the successful experience with live attenuated vaccines for paramyxoviruses (e.g., measles and mumps vaccines). However, the use of attenuated RSV vaccines has also been discouraging, with observed inadequate attenuation of viruses or reversion of genetic modifications (12, 4).

To safely elicit effective immune responses to RSV target antigens, we used a naturally attenuated xenotropic virus vector to express RSV G glycoprotein. In this study we examined the murine Sendai virus (SV) as the vaccine vector. We previously showed that SV is an effective, naturally attenuated live virus vaccine for its closely related (13, 20) human cognate, human parainfluenza virus type 1 (hPIV1) (8). Based on these preclinical findings and the known host-range restriction of SV (SV causes pneumonia in mice but no disease in humans [9]), we conducted a successful initial clinical study of intranasal SV as a vaccine for hPIV1 in human adults, demonstrating good tolerability (19). In this report we describe the use of reverse genetics to modify the SV cDNA backbone to express RSV G glycoprotein and our rescue of infectious recombinant SV (rSV RSVG). RSV G glycoprotein is a target of neutralizing antibody (24) and thus is a suitable vaccine candidate.

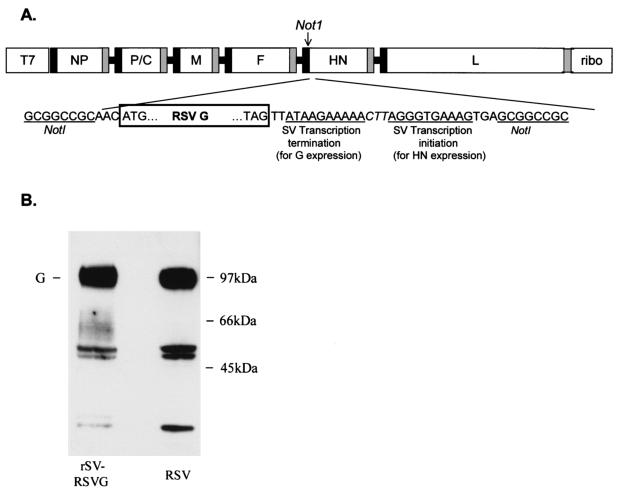

By using previously described methods (11), the full-length Z strain SV cDNA [pSeV(+)] from the nonsegmented, negative strand of SV was first modified to include a unique NotI site between the F and HN genes [pSV(+)N]. The RSV G gene was cloned from RNA extracted and amplified from RSV-infected HEp2 cells (RSV A2 strain) by using reverse transcription-PCR (Titan One Tube System; Roche). This RSV G PCR product was digested with NotI and cloned into the NotI site in pSV(+)N (Fig. 1). Successful recombinants were designated pSV(+)RSVG.

FIG. 1.

Design of pSV(+)RSVG and expression of RSV G target gene. (A) A unique NotI restriction enzyme site was created in the noncoding region of the HN gene to insert the RSV G glycoprotein gene. The NotI site was introduced into a subcloned ClaI-EcoRI fragment of pSeV(+) in pTF1 (21) by using a QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). This modified fragment was then substituted for the wild-type fragment in pSeV(+) to create pSV(+)N. RSV G gene was cloned by using a forward primer which included a NotI site and a reverse primer which included an SV transcription termination signal and another transcription initiation signal (separated by an intergenic linker sequence [CTT]), followed by the NotI site. Thus, RSV G transcription initiated from the upstream SV HN transcription initiation sequence and terminated by using the new termination sequence. SV HN transcription initiated by using the newly introduced transcription initiation sequence. T7, T7 promoter; ribo, hepatitis delta virus ribozyme sequence. Black and gray boxes represent transcription initiation and termination sequences, respectively, of the nucleoprotein (NP), polymerase (P), matrix (M), fusion (F), hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN), and large (L) protein. (B) Western blot examination of lysates of HEp-2 cells (approximately 106 cells) infected with rSV RSVG (left lane) or wild-type RSV (right lane). Cells were lysed with 0.2 ml of TNE buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM EDTA) and were clarified (15,000 × g, 10 min). Supernatants were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in nonreducing conditions, transferred to Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Danvers, Mass.), and developed with RSV G-specific monoclonal antibody (clone 63-10F; Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, Calif.). Fully glycosylated RSV G protein (both N- and O-linked glycosylation) runs at approximately 90 kDa (G). Middle band likely represents partially glycosylated G protein, and the lower band represents unglycosylated G.

Replicative, recombinant SV particles (rSV RSVG) were rescued by a reverse genetic system (modified from that described in reference 2). In brief, 293T cells (on 6-well plates) were infected with UV-inactivated, recombinant vaccinia virus vTF7.3 (for 1 h at 37°C; multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 3) which expresses T7 RNA polymerase. Cells were then cotransfected with pSV(+)RSVG (1 μg) and supporting plasmids expressing the NP, P, and L genes of SV (pTF1SVNP (1 μg), pTF1SVP (1 μg), and pTF1SVL (0.1 μg) (2, 22) in the presence of LipofectAMINE (8 μl; Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). Cells were maintained for 40 h (on Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-5% FCS) and then were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (100 μl). Lysates (freeze/thaw) were inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated eggs and allantoic fluid was harvested 72 h later. Recovered virus was cloned by plaque purification on LLC-MK2 cells to remove the vaccinia virus, and the cloned recombinant SV was amplified again in embryonated eggs to prepare a stock of rSV RSVG virus.

To confirm that the recombinant vector expressed glycosylated RSV G protein, lysates of rSV RSVG-infected HEp-2 cells (for 24 h at 34°C; MOI = 5) were examined by Western blot analysis. We observed a major band of fully glycosylated G protein as well as bands which likely represented partially glycosylated and unglycosylated G proteins (Fig. 1). Each of these bands were of the same size as bands produced by wild-type RSV. HEp-2 cells infected with SV alone were negative for RSV G expression.

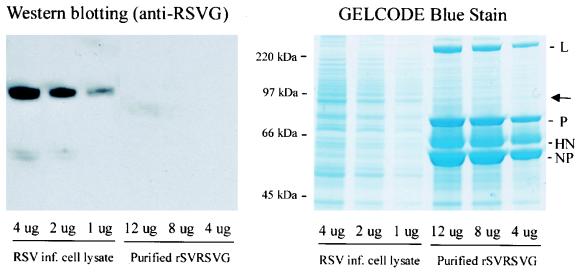

To ensure that the host-range specificity of the parent SV was not altered, recombinant SV particles were examined for the absence of incorporated RSV G; we proposed that the absence of a cytoplasmic tail domain would preclude incorporation of G into the SV particles (23). Purified rSV RSVG viral particles were subjected to Western blot analysis for RSV G, using an assay with a sensitivity of 1 pg (Fig. 2). Whereas the presence of RSV G protein was obvious in a control preparation of RSV-infected HEp2 cell lysate, RSV G protein could not be identified from purified recombinant SV particles, even when abundant virus (e.g., 12 μg of purified virus) was examined (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

rSV RSVG particles do not contain G protein. rSV RSVG viral particles were first purified from infected cell supernatant (HEp-2 cells; MOI 5; 72 h at 34°C) by sucrose gradient centrifugation and then resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). RSV-infected HEp2 cell lysates (control) were also run on SDS-PAGE. (Left) Gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet and were reacted with a monoclonal antibody directed against RSV G protein. The quantity of lysate run in each lane is indicated. RSV G detection assay (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent kit; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockland, Ill.) has a sensitivity of 1 pg. In contrast to the RSV G protein detected from all control preparations (RSV infected cell lysate), RSV G protein could not be detected from purified rSV RSVG, even with 12 μg of viral proteins. (Right) SDS-PAGE gels were also stained with GelCode Blue Stain Reagent (Pierce Biotechnology) to identify all proteins present in purified rSV RSVG particles. Arrow indicates the location of RSV G protein in the gel. SV protein abbreviations are the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 1.

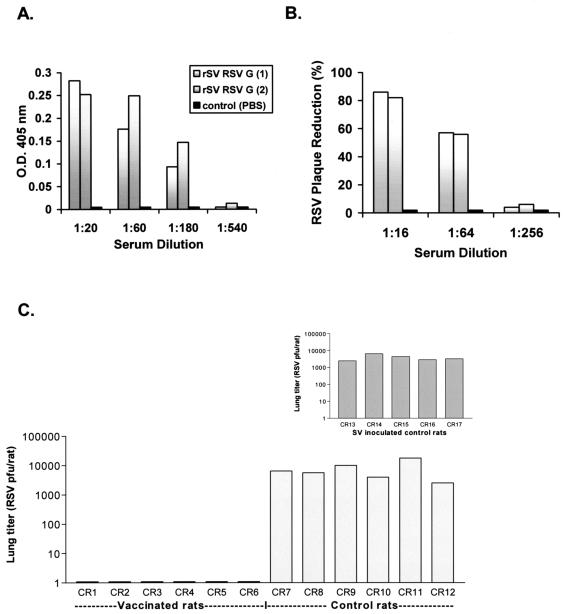

Having demonstrated effective expression of RSV G without evidence of incorporation of the foreign glycoprotein into recombinant virus particles, we next examined the capacity of rSV RSVG to elicit an immune response against the cloned gene. Cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus; Harlan, Indianapolis, Ind.) were immunized with rSV RSVG by the intranasal route (2 × 108 PFU), and blood was collected 7 weeks thereafter for antibody studies. 293T cells transfected with an RSV G expression plasmid (pCAGGS [15]) were used as a source of recombinant G protein for the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Specific anti-RSV G antibodies were detected from each of two immunized rats, in contrast to results for control animals (Fig. 3A). Examination of serum obtained from cotton rats 2 weeks following vaccination demonstrated substantial RSV neutralizing activity (>80% plaque reduction at 1:16 serum dilution; >50% plaque reduction at 1:64 serum dilution) compared to that of PBS-inoculated control animals (Fig. 3B). Results for binding and neutralizing antibody were consistent across repeated, separate immunization experiments. RSV-specific responses were not identified among control animals that received unmanipulated SV alone (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

rSV RSVG-primed cotton rats generate RSV-specific antibody. (A) Serial serum dilutions from immunized (gray bars) and control rats receiving PBS (black bars) were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. RSV G-transfected 293T cells served as the source of antigen. 293T cells grown in polylysine-coated 24-well plates were transfected with pCAGGS (0.5 μg; in LipofectAMINE) for 24 h. After transfection, wells were washed and reacted with serial dilutions of cotton rat test serum (in PBS-0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) for 30 min at room temperature (RT), washed again, and then reacted with rabbit anti-cotton rat IgG (1:3,000 in PBS-0.1% BSA; Virion Systems, Rockville, Md.) for 30 min at RT. Wells were washed and incubated with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:3,000 in PBS-0.1% BSA) for 30 min at RT. Wells were washed again and reacted with 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) substrate and measured by spectrophotometer. Results are reported as the absolute optical density at 405 nm (O.D. 405 nm) at each serum dilution. (B) RSV neutralizing activity was tested by plaque assay. Serum samples were mixed with RSV (100 to 500 PFU/well; 1 h at RT), and virus-serum mixtures were inoculated to HEp-2 cell monolayers (80 to 90% confluent) on 6-well plates, incubated for 1 h (37°C, 5% CO2), and then overlayed with medium containing methylcellulose. Plates were incubated for 7 days (37°C, 5% CO2), after which the methylcellulose was removed, the cells were fixed (formalin phosphate), and the plates were stained (hematoxylin and eosin) for plaque enumeration. Results are reported as the percent plaque reduction (y axis) observed at each serum dilution (x axis). (C) To measure protection from RSV challenge, sets of vaccinated (CR1 to CR6) and control (PBS recipients CR7 to CR12 and SV-inoculated CR13 to CR17, inset chart) were challenged with intranasal RSV (106 PFU) approximately 4 weeks after priming. Three days postchallenge animals were sacrificed, lungs were harvested, and lung tissue was cut into large fragments, mixed with PBS (1 ml), and processed with a mechanical Dounce homogenizer (PowerGen125 PCR Tissue Homogenizing kit; Fisher Scientific) over ice. Homogenates were then centrifuged and supernatants were collected and cryopreserved for virus quantitation (supernatant volume ranged between 4.0 to 6.5 ml/rat). RSV burden in lung supernatants was determined by plaque assay (see above) of serial dilutions of supernatants. Virus titers were determined by estimating the plaque number per volume plated, and the total virus burden per rat was calculated based on the total volume of supernatant obtained (reported along the y axis).

To measure protective efficacy of rSV RSVG, cotton rats were grouped to receive rSV RSVG vaccine (2 × 108 PFU of rSV RSVG, divided into two 30-μl inoculations), the same dose of unmanipulated SV, or the same volume of PBS, all by the intranasal route. Approximately 4 weeks later, all cotton rats were challenged with intranasal RSV (106 PFU/rat; Fig. 3C). Animals vaccinated with the recombinant SV construct were completely protected from challenge. In contrast, infection was consistently observed in rats primed with intranasal PBS or unmanipulated SV (lung titers were between 103 and 104 PFU/rat). Similar results were obtained in three separate challenge experiments. Given antigenic differences between the G glycoproteins of RSV subgroups A and B, additional experiments will be required to determine whether this subgroup A-based recombinant vaccine protects against challenge with the B subgroup or whether the preparation of a mixed vaccine (e.g., including G glycoproteins of both subgroups) will be required for protection.

Five days after intranasal RSV challenge, sets of vaccinated and control rats were sacrificed, lungs were harvested and perfused with formalin, and sections were prepared for histologic analysis. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained lungs were scored for inflammatory changes (bronchitis, peribronchiolitis, and alveolitis) in a blinded fashion and according to previously published criteria (16). Modest peribronchiolitis, alveolitis, and bronchitis were present in both control and vaccinated rats on the fifth day following RSV challenge (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Pulmonary histopathology following RSV challengea

| Animal group | Pathology

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchitis | Peribronchiolitis | Alveolitis | |

| Vaccinated | |||

| Expt 1 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

| Expt 2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| Control | |||

| Expt 1 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| Expt 2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 |

In two separate experiments, lungs were harvested from vaccinated (rSV RSVG) or control (inoculated with PBS [Expt 1] or SV [Expt 2]) rats on the fifth day after RSV challenge. RSV challenge was performed approximately 4 weeks after immunization or control inoculation. Mean scores and standard deviation obtained from each group (n = 5) of rats are shown. Results show that previous vaccination does not result in excess inflammation following RSV challenge compared to that of control animals.

Data presented here demonstrate that recombinant SV expressing the G glycoprotein of RSV elicits antibody responses directed against RSV and that vaccination provides protection from respiratory RSV challenge in the cotton rat model. Possibly, intranasal administration of SV vectors will also elicit local immunoglobulin A responses (19) and RSV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (7), both of which should be beneficial in protection against respiratory virus challenge (17, 10). These results illustrate the promise of recombinant SV as an intranasal vaccine vector and support the continued testing of rSV RSVG as a candidate vaccine for young children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH NCI grant P30 CA21765, the Children's Infection Defense Center (CIDC) at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

We thank Greg Prince and Ray Langley for providing the anti-cotton rat antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, L. J., R. A. Parker, and R. L. Strikas. 1990. Association between respiratory syncytial virus outbreaks and lower respiratory tract deaths of infants and young children. J. Infect. Dis. 161:640-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bousse, T., T. Matrosovich, A. Portner, A. Kato, Y. Nagai, and T. Takimoto. 2002. The long noncoding region of the human parainfluenza virus type 1 gene contributes to the read-through transcription at the M-F gene junction. J. Virol. 76:8244-8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connors, M., A. B. Kulkarni, C.-Y. Firestone, K. L. Holmes, H. C. Morse, A. V. Sotnikov, and B. R. Murphy. 1992. Pulmonary histopathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge of formalin-inactivated RSV-immunized BALB/c mice is abrogated by depletion of CD4+ T cells. J. Virol. 66:7444-7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowe, J. E., Jr., P. L. Collins, W. T. London, R. M. Chanock, and B. R. Murphy. 1993. A comparison in chimpanzees of the immunogenicity and efficacy of live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) temperature-sensitive mutant vaccines and vaccinia virus recombinants that express the surface glycoproteins of RSV. Vaccine 11:1395-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulginiti, V. A., J. J. Eller, O. F. Sieber, J. W. Joyner, M. Minamitani, and G. Meiklejohn. 1969. I. A field trial of two inactivated respiratory virus vaccines; an aqueous trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine and an alum-precipitated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Am. J. Epidemiol. 89:435-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heilman, C. A. 1990. From the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the World Health Organization. Respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 161:402-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou, S., L. Hyland, K. W. Ryan, A. Portner, and P. C. Doherty. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ T-cell memory determined by clonal burst. Nature 369:652-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurwitz, J. L., K. F. Soike, M. Y. Sangster, A. Portner, R. E. Sealy, D. H. Dawson, and C. Coleclough. 1997. Intranasal Sendai virus vaccine protects African green monkeys from infection with human parainfluenza virus-type one. Vaccine 15:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishida, N., and M. Homma. 1978. Sendai virus. Adv. Virus Res. 23:349-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kast, W. M., L. Roux, J. Curren, H. J. Blom, A. C. Voordouw, R. H. Meloen, D. Kolakofsky, and C. J. Melief. 1991. Protection against lethal Sendai virus infection by in vivo priming of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes with a free synthetic peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2283-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato, A., Y. Sakai, T. Shioda, T. Kondo, M. Nakanishi, and Y. Nagai. 1996. Initiation of Sendai virus multiplication from transfected cDNA RNA with negative or positive sense. Genes Cells 1:569-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, H. W., J. O. Arrobio, G. Pyles, C. D. Brandt, E. Camargo, R. M. Chanock, and R. H. Parrott. 1971. Clinical and immunological response of infants and children to administration of low-temperature adapted respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatrics 48:745-755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyn, D., D. S. Gill, R. A. Scroggs, and A. Portner. 1991. The nucleoproteins of human parainfluenza virus type 1 and Sendai virus share amino acid sequences and antigenic and structural determinants. J. Gen. Virol. 72:983-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy, B. R., G. A. Prince, E. E. Walsh, H. W. Kim, R. H. Parrott, V. G. Hemming, W. J. Rodriguez, and R. M. Chanock. 1986. Dissociation between serum neutralizing and glycoprotein antibody responses of infants and children who received inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. J. Clin. Microbiol. 24:197-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niwa, H., K. Yamamura, and J. Miyazaki. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prince, G. A., J. P. Prieels, M. Slaoui, and D. D. Porter. 1999. Pulmonary lesions in primary respiratory syncytial virus infection, reinfection, and vaccine-enhanced disease in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus). Lab. Investig. 79:1385-1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell, M. W., M. H. Martin, H.-Y. Wu, S. K. Hollingshead, A. Moldoveanu, and J. Mestecky. 2000. Strategies of immunization against mucosal infections. Vaccine 19:S122-S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simoes, E. A. F. 1999. Respiratory syncytial virus infection. Lancet 354:847-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slobod, K. S., J. L. Shenep, J. Lujan-Zilbermann, K. Allison, B. Brown, R. A. Scroggs, A. Portner, C. Coleclough, J. L. Hurwitz. Safety and immunogenicity of intranasal murine parainfluenza virus type 1 (Sendai virus) in healthy adults. Vaccine, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Smith, F. S., A. Portner, R. J. Leggiadro, E. V. Turner, and J. L. Hurwitz. 1994. Age-related development of human memory T-helper and B-cell responses towards parainfluenza virus-type 1. Virology 205:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi, T., K. W. Ryan, and A. Portner. 1993. A plasmid that improves the efficiency of foreign gene expression by intracellular T7 RNA polymerase. Genet. Anal. Technol. Appl. 9:91-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takimoto, T., T. Bousse, and A. Portner. 2000. Molecular cloning and expression of human parainfluenza virus type 1 L gene. Virus Res. 70:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takimoto, T., T. Bousse, E. C. Coronel, R. A. Scroggs, and A. Portner. 1998. Cytoplasmic domain of Sendai virus HN protein contains a specific sequence required for its incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 72:9747-9754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor, G., E. J. Stott, M. Bew, B. F. Fernie, P. J. Cote, A. P. Collins, M. Hughes, and J. Jebbett. 1984. Monoclonal antibodies protect against respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. Immunology 52:137-142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]