Abstract

Children under age six years are disproportionately exposed to interpersonal trauma, including maltreatment and witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV), and may be particularly susceptible to negative sequelae. However, young children have generally been neglected from trauma research; thus, little is known about the factors influencing vulnerability to traumatic stress responses and other negative outcomes in early life. This study examined associations among interpersonal trauma exposure, sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in 200 children assessed prospectively from birth to 1st grade via home and laboratory observations, record reviews, and maternal and teacher interviews. Greater trauma exposure and sociodemographic risk and lower developmental competence predicted more severe PTSD symptoms. Developmental competence partially mediated the association between exposures and symptoms. Trauma exposure fully mediated the association between sociodemographic risk and symptoms. Neither sociodemographic risk nor developmental competence moderated trauma exposure effects on symptoms. The findings suggest that (a) exposure to maltreatment and IPV has additive effects on posttraumatic stress risk in early life, (b) associations between sociodemographic adversity and poor mental health may be attributable to increased trauma exposure in disadvantaged populations, and (c) early exposures have a negative cascade effect on developmental competence and child mental health.

Young children (< 6 years) have been largely excluded from traumatic stress studies, as the field was long dominated by the belief that young children are not affected by trauma (Scheeringa, Zeanah, Myers, & Putnam, 2005). However, evidence suggests that young children may be highly vulnerable to severe and persistent traumatic stress responses and other negative developmental sequelae and are therefore in urgent need of study (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, & Ford, 2012; Scheeringa & Zeanah, 2001; Scheeringa et al., 2005). There is a particular need for prospective research to determine the factors that influence responses to early trauma exposures. Relevant considerations include qualities of the traumatic event, the child’s developmental functioning, and contextual features. An enhanced understanding of the factors that increase vulnerability to pathological outcomes is critical for designing effective intervention and prevention efforts.

The most prevalent traumatic exposures in the first years of life include maltreatment and witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2012; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Fantuzzo & Fusco, 2007). Moreover, trauma involving the caregiver as perpetrator (maltreatment) or victim (IPV) appears especially damaging to young children’s mental health, presumably due to the central role of the caregiver in early development (Scheeringa & Zeanah, 2001). Such exposures have been linked to a range of psychopathology, with exposures in early childhood associated with more severe and enduring effects than later exposures in some studies (Edleson, 1999; Kitzmann, Gaylord, & Holt, 2003; MacMillan et al., 2001; Maughan, & Cicchetti, 2002; Scheeringa, Wright, Hunt, & Zeanah, 2006; Scheeringa & Zeanah, 1995; Yates, Dodds, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2003). A few studies have reported associations between exposures to such interpersonal traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in children as young as one year of age (Bogat, DeJonghe, Levendosky, Davidson, & von Eye, 2006). Though there is evidence that exposure to multiple types of trauma has an additive effect on PTSD risk (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007; Graham-Bermann, Castor, Miller, & Howell, 2012) and that maltreatment and exposure to IPV frequently co-occur, research has largely focused on the effects of either IPV or maltreatment on mental health outcomes (Dong et al., 2004; Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008). The limited studies that have examined the effects of exposure to one versus both types of trauma on child mental health have produced inconsistent findings, with some showing additive influences, others showing no additional impact from one versus both exposure types, and others showing interaction effects among number of exposures, child age, and symptom type (Kitzmann et al., 2003; Maughan, & Cicchetti, 2002; Sternberg, Baradaran, Abbott, Lamb, & Guterman, 2006). Thus, studies are needed to determine whether exposure to both trauma types in early life is associated with more severe PTSD symptoms than exposure to one type.

Early exposure to interpersonal trauma may also have detrimental effects on developmental competence, i.e., the effectiveness and quality of individual adaptation in the use of internal and external resources to successfully negotiate developmentally salient issues (Obradović, van Dulmen, Yates, Carlson, & Egeland, 2006). Maltreatment and exposure to IPV have been associated with developmental maladaptation in early childhood (Cicchetti & Toth, 2000; Egeland, Yates, Appleyard, & van Dulmen, 2002; Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz, & Lilly, 2010; Levendosky, Bogat, Huth-Bocks, Rosenblum, & von Eye, 2011). Because prior forms of adaptation become hierarchically integrated into later adaptational patterns, early exposures may have a lasting impact on child functioning (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2012). Maladaptation at any stage represents a departure from normal development that may initiate a pathway toward psychopathology (Egeland et al., 2002). Conversely, the presence of psychopathology may interfere with the achievement of developmental milestones (Masten & Curtis, 2000). Furthermore, developmental competence may moderate associations between trauma exposure and mental health outcomes, with diminished competence increasing vulnerability to more severe or persistent traumatic stress symptoms. Little research has examined the interrelations between PTSD and developmental competence following trauma exposure, particularly in early childhood (Milot, Éthier, St-Laurent, & Provost, 2010).

Contextual factors may also influence a child’s response to early interpersonal trauma. Child maltreatment and IPV frequently occur within a larger disrupted social environment, including low socioeconomic status (SES), young maternal age, and inadequate social support (Fantuzzo & Fusco, 2007; Holt et al., 2008; Moffitt & the E-risk Study Team, 2002; Yates et al., 2003). Adverse sociodemographic conditions may have additive effects, increasing risk for poor outcomes beyond that associated with trauma exposure (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2012; Holt et al., 2008). Sociodemographic status may also act as a moderator, with trauma exposure having more damaging effects in children living with greater adversity. Trauma exposure may also mediate links between sociodemographic risk and mental health: Associations between mental health difficulties and sociodemographic factors may be attributable, at least in part, to increased trauma exposure among disadvantaged populations (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009).

The goal of the current study was to examine prospectively associations among interpersonal trauma exposure (maltreatment, IPV), sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms in a community birth cohort followed to first grade to test the following hypotheses: (1) Sociodemographic risk moderates the impact of trauma on PTSD symptoms. (2) Developmental competence moderates the impact of trauma on PTSD symptoms. (3) Trauma mediates the association between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms. (4) Developmental competence mediates the association between trauma and PTSD symptoms. In an exploratory aim, sex differences in the patterns of associations were tested, as existing data are inconsistent in indicating how sex may moderate responses to interpersonal trauma, particularly in early life (Bogat et al., 2006; Edleson, 1999; Holt et al., 2008; Yates et al., 2003).

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 200 dyads) were from the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation (MLSRA), a prospective examination of adaptation in low-income families (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005). Primiparous women were recruited during the third trimester from the Minneapolis Department of Public Health Clinic and the Hennepin County General Hospital between 1975 and 1977. Mothers were eligible if their income was below the official poverty line. At the child’s birth, mothers were between 12 and 34 years old (M = 20.61 years, SD = 3.76; 17% < 18 years); 64% were not married (single, separated, divorced, widowed), and 39% had not completed high school (M = 11.77 years of education, SD = 1.80, range = 7 to 20 years). Children’s racial/ethnic composition was 65% White, 18% multi-racial, 12% Black, 4% Native American, 1% Hispanic, and 1% Asian; 55% were male. The University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. Mothers provided written informed consent.

Procedures and Measures

Sociodemographic risk factors

A sociodemographic risk score was calculated by assigning one point for each of the following: mother unmarried at child’s birth; mother < 18 years at child’s birth; mother not completed high school by child’s birth; SES (based on mean standardized z-scores from at least two sources: mother’s level of education, household income, revised Duncan Socioeconomic Index household score [Duncan, 1961; Stevens & Featherman, 1981]) at 42 months or 1st grade in bottom 25–30% of sample; child of racial/ethnic minority group.

Interpersonal trauma exposure

Events included maltreatment and witnessing IPV. A score was derived based on the child’s history, with possible scores of “0” (no exposure to maltreatment or IPV), “1” (exposure to either maltreatment or IPV), or “2” (exposure to both maltreatment and IPV).

Maltreatment

Maltreatment was identified prospectively through repeated home (7–10 days and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months) and videotaped laboratory observations (9, 12, 18, 24, and 42 months); repeated structured maternal interviews throughout assessment periods; and reviews of medical and child protection records at 24 and 64 months. Children were classified as maltreated if there was evidence of any of the following: (a) physical abuse, defined as parental acts resulting in physical damage (e.g., bruises, cuts, burns); (b) emotional maltreatment, defined as emotional abuse (e.g., constant harassment or berating, chronically finding fault, harsh criticism) or emotional neglect (e.g., interacting only as necessary, emotional unresponsiveness); (c) physical neglect, defined as incompetent and irresponsible management of the child’s day-to-day care, inadequate nutritional or health care, or dangerous home environment due to insufficient supervision; (d) sexual abuse, defined as genital contact between the child and a person ≥ 5 years older (all perpetrators were adolescents or adults). Using information from observations, maternal interviews, and record reviews, MLSRA staff classified participants as maltreated or not maltreated, reaching near perfect agreement. At least three raters classified each participant; any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. Validation for the identification of maltreatment cases has been previously reported (Shaffer, Huston, & Egeland, 2008; Shaffer, Yates, & Egeland, 2009).

Witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV)

Ratings of child IPV exposure were based on maternal interviews and questionnaires and interviewer observations of the families at 12, 18, 24, 30, 42, 48, 54, and 64 months. Trained coders rated the frequency and severity of physical violence toward the mother by her partner in the home as reported by the mother following comprehensive review of all data in a given time period (see Yates et al., 2003 for full scale). Inter-rater reliability was calculated at each time-point on the basis of 50 ratings (rs = .93-.99). As previously done (Ogawa, Sroufe, Weinfield, Carlson, & Egeland, 1997) and suggested by others (Kitzmann et al., 2003), children with a score indicative of severe IPV exposure (i.e., potential for serious injury, often accompanied by death threats) were classified as having been trauma-exposed. Such exposures have been hypothesized to be similar to maltreatment with regard to impact on child outcomes (Bogat et al., 2006; Kitzmann et al., 2003).

Developmental competence

Developmental competence was assessed at two time-points using validated measures informed by theory regarding the key issues for adaptation at each developmental stage (Obradović et al., 2006; Sroufe et al., 2005). The preschool competence measure was based on the conceptualization of the preschool years as a period marked by rises in self-direction, agency, self-management, and self-regulation (Sroufe et al., 2005). The school-age competence measure included ratings of emotional well-being and social (particularly peer) and cognitive functioning, domains theorized to be salient as children negotiate entrance to formal schooling (Obradović et al., 2006; Sroufe et al., 2005). On both developmental competence scales, higher scores indicate greater competence.

Preschool

At 42 months, children participated in the Barrier Box task (Harrington, Block, & Block, 1978), a videotaped procedure meant to challenge the child’s regulatory capacities. The child was presented with a locked plexiglass box full of attractive toys and easily accessible undesirable toys and told he/she could play with either set, though the box could not be opened. The child was given 10 minutes to try to open the box and/or play with the undesirable toys. The preschool competence measure was derived by summing the standardized scores from the following 5- to 7-point scales, each scored by two observers (average inter-rater reliability r = .88): (a) self-esteem—degree of interest, curiosity, enthusiasm, and ability to stay organized, constructive, involved; (b) flexibility—degree to which a range of tactics were attempted versus the same futile approaches were repeated or the child became disorganized; (c) agency—confidence, vigor, assertiveness; (d) positive affect—enthusiasm, delight, excitement; (e) negative affect (reverse scored)—distress, crying, anger, frustration, general negativity. Scores on this measure were previously shown to be significantly associated with earlier (12, 18, 24 months) and later (54 months) ratings of developmental competence in this sample, supporting its validity (Sroufe et al., 2005).

School-age

The school-age competence measure was created from several instruments administered to the participants’ teachers in Kindergarten and 1st grade. Teachers rank ordered the children in the participant’s classroom on emotional health/self-esteem and social competence. Emotional health/self-esteem referred to the child’s ability to take advantage of what the classroom offered, enjoy social and academic activities, and engage in new experiences and challenges. Social competence referred to the child’s effectiveness in the peer group, including sociability, acceptance among other children, friendship, social skills, and leadership qualities. Teachers were not informed which student was the study subject prior to completing these rankings. Additionally, a work-habits scale was created by adding the standardized scores of the following 5- to 6-point scales obtained from structured teacher interviews: enjoyment of learning, persistence, ability to work independently, ability to express self, needs teacher’s approval (reverse-scored), needs encouragement and reassurance (reverse-scored), becomes easily frustrated (reverse-scored). The correlation coefficients among the scales ranged from .64 to .80. The scales were standardized and summed to create a competence score, which has previously been shown to be associated with earlier (12, 18, 42 months) and later (11, 16 years) ratings of developmental competence in this sample, supporting its validity (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006).

Childhood PTSD symptoms

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the parent and teacher report forms of the Child Behavior Checklist, a measure of emotional and behavioral symptoms. Mothers completed the CBCL (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) when the children were 64 months old and in 1st grade. Teachers completed the CBCL: Teacher’s Report Form (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986) in April or May of Kindergarten and 1st grade. Both report forms show high test-retest reliabilities (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983, 1986). The CBCL-PTSD scale consists of 20 items chosen for overlap with DSM-III PTSD symptoms (Wolfe, Gentile, and Wolfe, 1989). The scale has demonstrated high internal consistency and significant correlations with several measures of PTSD (Wolfe, Gentile, Michienzi, Sas, & Wolfe, 1991) and has been shown to discriminate between children who were and were not sexually abused (Wolfe & Brit, 1997) and to decline between pre- and post-treatment among children treated for PTSD diagnosed using DSM-IV criteria (King et al., 2000). A modified version of the CBCL-PTSD scale tested in children ages 2 to 6 years demonstrated adequate sensitivity and specificity in identifying children diagnosed with PTSD (Dehon & Scheeringa, 2006). In the current sample, the CBCL-PTSD scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency across reports, Cronbach’s αs = .76-.81. A PTSD symptoms score was formed using the highest achieved standardized z-score among available reports.

Data Analytic Plan

Distributions of the variables were examined. Due to non-normality of some variables, sex differences were tested via Mann-Whitney U tests. Bivariate associations among the study variables were tested in Spearman’s rank order correlational analyses. Differences in sociodemographic risk, preschool and school-age developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms by interpersonal trauma exposure were tested by Mann-Whitney U tests. A series of linear regression analyses were run to test moderation hypotheses. Finally, a series of path analyses were fit, and a path model was developed in which multiple pathways of effects were tested simultaneously for each of the competence measures. The final path models were tested for sex differences by testing equality of paths across sexes via multi-group analysis in Mplus. Mediation was tested within the path models fit in Mplus, which uses the delta method to test for significance of an indirect effect (MacKinnon, 2008). Estimation for linear regression and path analyses performed was via full information maximum likelihood to account for missing data. Estimates of standardized regression coefficients (β), the path coefficient test statistic (z, equal to the estimated regression coefficient divided by the standard error), and the associated p-value are presented. Descriptive analyses and correlational and Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted in SPSS (version 19); linear regression, path analyses, and multi-group analysis were conducted in Mplus (version 5.2). For all analyses, p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Participants with data for at least one of the five main study variables were included in analyses. Of the 267 families recruited into MLSRA, 200 participants provided data for at least one variable: 163 had data for sociodemographic risk, trauma, PTSD symptoms, and at least one of the two competence variables; 15 were missing data for one, 13 for two, and 9 for three of these variables. The majority of MLSRA attrition occurred in the first two years: Of the 67 excluded families, 43 did not provide data after the pregnancy assessment, and 59 did not provide data at the 24-month assessment. There were no differences between families who were and were not included in the current study on maternal race, age, education, marital status, or SES at the child’s birth or child race/ethnicity or sex, all ps >.30.

Results

Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

Between birth and 64 months of age, 38% of participants experienced interpersonal trauma, with 28% experiencing maltreatment only, 3% witnessing IPV only, and 7% exposed to both maltreatment and IPV. Among those maltreated, 49% were physically abused, 54% emotionally maltreated, 48% neglected, and 18% sexually abused. In Mann-Whitney U tests, males and females did not differ significantly on sociodemographic risk, interpersonal trauma, preschool or school-age developmental competence, or PTSD symptoms, all ps > .05. The bivariate associations among sociodemographic risk, interpersonal trauma, preschool and school-age competence, and PTSD symptoms were all significant except the association between sociodemographic risk and preschool competence (Table 1).

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlation Coefficients among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexa | -- | ||||

| 2. Sociodemographic risk | −.01 | -- | |||

| 3. Interpersonal trauma exposure | −.07 | .34*** | -- | ||

| 4. Developmental competence, preschool | −.04 | −.05 | −.19* | -- | |

| 5. Developmental competence, school-age | .14 | −.28*** | −.40*** | .23** | -- |

| 6. PTSD symptoms | .04 | .22** | .43*** | −.31*** | −.54*** |

Male children were coded “1”; female children were coded “2.”

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Sociodemographic Risk, Developmental Competence, and PTSD Symptoms by Interpersonal Trauma Exposure

Mann-Whitney U tests compared exposure to (a) no versus any interpersonal trauma and (2) one versus both types of interpersonal trauma on sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms (Table 2).1 In Mann-Whitney U tests comparing no exposure to any exposure, exposure to any interpersonal trauma was associated with greater sociodemographic risk (Z = −4.23, p < .001), lower preschool competence (Z = −2.61, p = .009), lower school-age competence (Z = −5.20, p < .001), and greater PTSD symptoms (Z = −5.30, p < .001). In Mann-Whitney U tests comparing exposure to one versus both types, exposure to both types was associated with greater PTSD symptoms (Z = −2.07, p = .038) but not to differences in sociodemographic risk (Z = −0.85, p = .397), preschool competence (Z = −0.36, p = .720), or school-age competence (Z = −0.96, p = .338).

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations on Sociodemographic Risk, Developmental Competence, and PTSD Symptoms Scores by Interpersonal Trauma Exposure History

| Interpersonal Trauma Exposure Group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Exposed to Maltreatment or Partner Violence Against Mother | Exposed to Maltreatment or Partner Violence Against Mother | Exposed to Maltreatment and Partner Violence Against Mother | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Sociodemographic risk | 1.69 | 1.63 | 2.83 | 1.83 | 3.27 | 1.42 |

| Developmental competence | ||||||

| Preschool | 0.59 | 3.75 | −1.09 | 3.33 | −0.74 | 4.14 |

| School-age | 0.30 | 1.01 | −0.62 | 0.74 | −0.40 | 0.72 |

| PTSD symptoms | 0.54 | 0.96 | 1.28 | 0.99 | 1.96 | 0.85 |

Note. Exposure to any trauma (maltreatment, partner violence) was associated with greater sociodemographic risk, lower preschool and school-age competence, and greater PTSD symptoms than exposure to no trauma (ps < .01). Exposure to both trauma types (maltreatment and partner violence) was associated with greater PTSD symptoms than exposure to one type (p = .038).

Interpersonal Trauma Exposure, Sociodemographic Risk, and Developmental Competence Predicting PTSD Symptoms

Regression analyses testing moderation hypotheses

Three separate linear regression analyses were run to test whether the impact of interpersonal trauma on PTSD symptoms was moderated by sociodemographic risk (Hypothesis 1) or by preschool or school-age developmental competence (Hypothesis 2). In the first analysis, the interaction term and the main effect terms for interpersonal trauma and sociodemographic risk were included in the model; the interaction term was not significant, β = 0.13, z = 0.77, p = .440. In the next two analyses, the interaction term and the main effect terms for interpersonal trauma and developmental competence were included in the model; separate models were run for preschool and school-age developmental competence. Neither the preschool nor school-age interaction term was significant, β = 0.03, z = 0.33, p = .739 and β = −0.01, z = −0.07, p = .941, respectively. Therefore, there was no evidence that sociodemographic risk or developmental competence moderated the impact of interpersonal trauma on PTSD symptoms.

Path analyses testing mediation hypotheses

The mediation hypotheses were tested in stages in separate path analyses for preschool and school-age developmental competence. The first step tested whether interpersonal trauma mediated the association between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms (Hypothesis 3). There was a significant indirect effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms through trauma, β = 0.13, z = 3.54, p < .001; the direct effect of sociodemographic risk on PTSD symptoms was no longer significant, β = 0.08, z = 1.12, p = .264, indicating full mediation by interpersonal trauma. The next step evaluated whether developmental competence mediated the association between interpersonal trauma and PTSD symptoms (Hypothesis 4). There was a significant indirect effect between trauma and PTSD symptoms through preschool competence, β = 0.04, z = 2.04, p = .041, in addition to a significant direct effect, β = 0.38, z = 5.90, p < .001, indicating partial mediation by preschool competence. Similarly, there was a significant indirect effect between trauma and PTSD symptoms through school-age competence, β = 0.15, z = 4.19, p < .001, in addition to a significant direct effect, β = 0.27, z = 4.05, p < .001, indicating partial mediation by school-age competence.

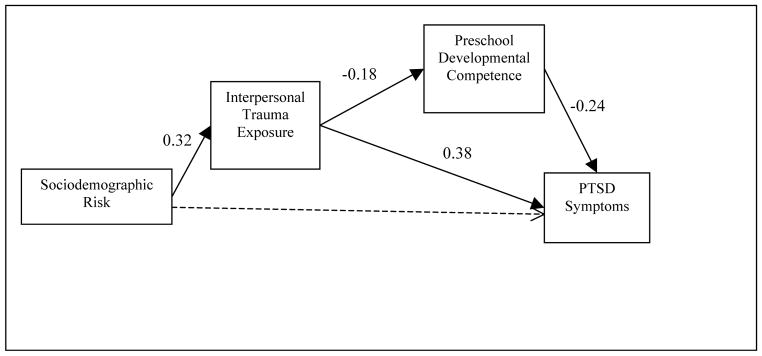

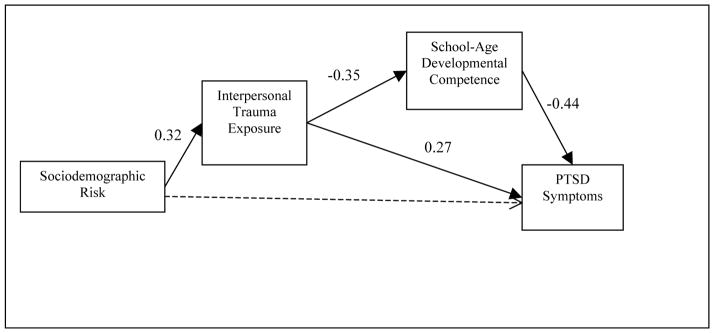

The full conceptual model was tested separately for preschool and school-age competence by combining the two mediational effects. Given the lack of a significant direct effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms once interpersonal trauma was included in the path, the full models excluded the direct path between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms. Both the model including preschool competence (Figure 1) and the model including school-age competence (Figure 2) fit the data well: chi-square = 1.30, df = 2, p = .523, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA < .0001 and chi-square = 4.27, df = 2, p = .118, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = .076, respectively. All but one path were statistically significant. When preschool competence was included in the model, the indirect effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms through trauma was significant, β = 0.12, z = 3.57, p < .001, as was the indirect effect between trauma and PTSD symptoms through competence, β = 0.04, z = 2.07, p = .039, whereas the indirect effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms through trauma and competence did not reach significance, β = 0.01, z = 1.87, p = .061. When school-age competence was included in the model, the indirect effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms through trauma was significant, β = 0.09, z = 3.00, p = .003, as was the indirect effect between trauma and PTSD symptoms through competence, β = 0.15, z = 4.18, p < .001, and the indirect effect between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms through trauma and competence, β = 0.05, z = 3.05, p = .002.

Figure 1.

Path analysis of the associations among sociodemographic risk, interpersonal trauma exposure, preschool developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms. Values are standardized betas, all significant at p < .05. Dotted line indicates non-significant path removed from final model.

Figure 2.

Path analysis of the associations among sociodemographic risk, interpersonal trauma exposure, school-age developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms. Values are standardized betas, all significant at p < .05. Dotted line indicates non-significant path removed from final model.

The final models were tested for differences by sex by testing the equality of paths by sex (exploratory aim). There was no evidence for significant sex differences when either the preschool or school-age developmental competence measure was included, ps = .82 and .76, respectively.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine associations among interpersonal trauma exposure—specifically, maltreatment and witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) against the mother—and sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and childhood PTSD symptoms in a community low-income birth cohort followed to 1st grade. Greater sociodemographic risk was associated with increased likelihood of interpersonal trauma exposure, and both of these variables were associated with more severe PTSD symptoms. These findings are consistent with research showing that a number of sociodemographic risk factors (e.g., poverty, single or adolescent parenthood, inadequate social support) are associated with greater risk for trauma exposure and with increased rates of mental health problems (Fantuzzo & Fusco, 2007; Holt et al., 2008; Moffitt & the E-risk Study Team, 2002; Sameroff, 1998; Williams et al., 1990; Yates et al., 2003). The finding that interpersonal trauma exposure fully mediated the association between sociodemographic risk and PTSD symptoms suggests that previously documented increased rates of mental health difficulties in disadvantaged populations may be due, at least in part, to increased rates of trauma exposure. Thus, mental health interventions with children living in adversity should consider assessing trauma exposure history and addressing traumatic stress symptoms.

Poor developmental competence partially mediated the association between interpersonal trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms. These findings are consistent with developmental psychopathology theories that posit intimate links between developmental competence and psychopathology (Masten & Curtis, 2000; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). Analyses did not test whether PTSD symptoms mediated associations between interpersonal trauma exposure and developmental competence, in part because there was no measure of PTSD symptoms prior to the developmental competence assessments. Other studies have indicated that the presence of traumatic stress symptoms may impair later psychosocial adjustment, though such studies have tended to define adjustment using measures of emotional and behavioral problems rather than developmental adaptation (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2012; Milot et al., 2010). Given the hierarchical organizational nature of development and the hypothesized transactional relationship between developmental competence and psychopathology, traumatic stress symptoms and developmental maladaptation likely have bidirectional influences on each other over the course of development. Thus, exposure to interpersonal trauma in early life may initiate a trajectory marked by both psychopathology and developmental maladaptation that, without intervention, cascades toward increasing dysfunction over time (Obradović, Burt, & Masten, 2010).

Exposure to both maltreatment and IPV was associated with more severe PTSD symptoms than exposure to either, suggesting that these exposures have additive effects on PTSD risk in early life. These results are consistent with findings that exposure to multiple trauma types predicts more severe traumatic stress symptoms in children than exposure to any individual trauma and that maltreatment may have particular impact (Finkelhor et al., 2007). Notably, this study’s maltreatment measure included assessment of emotional abuse and neglect. Though these forms of maltreatment have been linked to poor psychosocial functioning and traumatic stress symptoms, they have been largely ignored in the trauma literature, which has focused heavily on physical and sexual abuse (Dong et al., 2004; Milot et al., 2010; Shaffer et al., 2009). Future research should explore how frequency and timing of trauma exposures and exposure to various combinations of trauma, including different types of maltreatment, may differentially influence developmental competence and PTSD risk in young children.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to examine associations among maltreatment and IPV exposure, sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms in early life. The prospective, repeated, multi-informant, multi-dimensional assessment design differs from the many trauma studies that are cross-sectional, retrospective, and/or reliant on exposed individuals’ self-report for predictor and outcome data. Drawing from a community sample reduced the biases inherent in using clinical samples or samples drawn via child protection records or from domestic violence shelters, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the results (Holt et al., 2008).

The intensive nature of the assessments necessitated a relatively small sample size, which may have lowered the power to detect sex effects or moderating influences of sociodemographic risk or developmental competence on the association between trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms. PTSD symptoms were assessed using a general symptomatology questionnaire, not a diagnostic clinical interview, and thus were not required to have developed in response to an identifiable traumatic event. Symptoms on the CBCL-PTSD scale may have been present among children not exposed to trauma (thus reflecting more general emotional/behavioral issues) or may have been attributable to unmeasured trauma exposures (e.g., accident). Ideally, mediating variables (developmental competence) are assessed after predictor variables (trauma) and before outcome variables (PTSD symptoms). This design was not completely achievable due to the variable timing (i.e., different participants exposed at different ages) and sometimes chronic nature (i.e., participants exposed to multiple events over time) of trauma exposures. An effort was made to measure exposures from earlier periods (birth to 64 months) than developmental competence (42 and 64 months) and to measure developmental competence at earlier periods than PTSD symptoms (64+ months). The issue of timing was partially addressed by testing the meditational model using developmental competence at two different time-points, with no substantial difference in results; however, a true causal relationship among these variables cannot be completely confirmed. The results may not generalize to populations with lower sociodemographic risk who have greater access to resources that may attenuate trauma exposure effects. The hypotheses should be tested in a more contemporary sample.

Conclusion

Children under age six years are at elevated risk for exposure to maltreatment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010) and domestic violence (Fantuzzo & Fusco, 2007). The current findings suggest that exposure to such traumas in early life may contribute to the disruption of the achievement of salient developmental tasks and that such disruptions are associated with more severe PTSD symptoms in childhood. Children living in adverse sociodemographic conditions may be at especially heightened risk for early interpersonal trauma exposures. Efforts to identify at-risk children, prevent exposures, and provide effective, early treatments for those exposed may help prevent or reverse a negative cascade of effects marked by developmental maladaptation and psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants to the last author from the Maternal and Child Health Service (MCR-270416), the William T. Grant Foundation, New York, and the National Institute of Mental Health (MH-40864). During preparation of this manuscript, the authors were supported by K08MH074588 and the Program for Behavioral Science in the Department of Psychiatry at Boston Children’s Hospital (Bosquet Enlow) and R01HD054850 (Egeland). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the granting agencies. The authors thank the research staff responsible for data collection and the families and teachers whose generous donation of time made this project possible.

Footnotes

Because the CBCL-PTSD scale was not part of the original CBCL, T-scores are not available. Of the 20 PTSD items, 13 appear on the CBCL Internalizing scale. To provide context for the magnitude of symptomatology in this sample, mean Internalizing T-scores are presented by interpersonal trauma exposure group: no exposure = 61.07 (SD = 7.71); exposure to one type = 64.94 (SD = 7.86); exposure to both types = 68.00 (SD = 6.59).

Contributor Information

Michelle Bosquet Enlow, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Emily Blood, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Byron Egeland, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bogat GA, DeJonghe E, Levendosky AA, Davidson WS, von Eye A. Trauma symptoms among infants exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:109–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet M, Egeland B. The development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:517–550. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Ford JD. Parsing the effects violence exposure in early childhood: Modeling developmental pathways. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37:11–22. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsro63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child maltreatment: Facts at a glance. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/CM-DataSheet-a.pdf.

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Developmental processes in maltreated children. In: Hansen D, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Vol. 46: Child maltreatment. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehon C, Scheeringa MS. Screening for preschool posttraumatic stress disorder with the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:431–435. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thomspon TJ, Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan O. A socioeconomic index for all occupations. In: Reiss AJ Jr, editor. Occupations and social status. New York, NY: Free Press; 1961. pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Edleson JL. Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:839–870. doi: 10.1177/088626099014008004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Yates T, Appleyard K, van Dulmen M. The long-term consequences of maltreatment in the early years: A developmental pathway model to antisocial behavior. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, & Practices. 2002;5:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, Fusco RA. Children’s direct exposure to types of domestic violence crime: A population-based investigation. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:543–552. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9105-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Bermann SA, Castor LE, Miller LE, Howell KH. The impact of intimate partner violence and additional traumatic events on trauma symptoms and PTSD in preschool-aged children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:393–400. doi: 10.1002/jts.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington D, Block JH, Block J. Intolerance of ambiguity in preschool children: Psychometric considerations, behavioral manifestations, and parental correlates. Developmental Psychology. 1978;14:242–256. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.14.3.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell KH, Graham-Bermann SA, Czyz E, Lilly M. Assessing resilience in preschool children exposed to intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:150–164. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, Myerson N, Heyne D, Rollings S, Ollendick TH. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann K, Gaylord N, Holt A. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, Huth-Bocks AC, Rosenblum K, von Eye A. The effects of domestic violence on the stability of attachment from infancy to preschool. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;40:398–410. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.563460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, Beardslee WR. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan A, Cicchetti D. Impact of child maltreatment and interadult violence on children’s emotion regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1525–1542. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Curtis WJ. Integrating competence and psychopathology: Pathways toward a comprehensive science of adaptation in development. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:529–550. doi: 10.1017/s095457940000314x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milot T, Éthier LS, St-Laurent D, Provost MA. The role of trauma symptoms in the development of behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE the E-risk Study Team. Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Burt KB, Masten AS. Testing a dual cascade model linking competence and symptoms over 20 years from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:90–102. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, van Dulmen MHM, Yates TM, Carlson EA, Egeland B. Developmental assessment of competence from early childhood to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:857–889. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.004.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa JR, Sroufe LA, Weinfield NS, Carlson EA, Egeland B. Development and the fragmented self: Longitudinal study of dissociative symptomatology in a nonclinical sample. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:855–879. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Wright MJ, Hunt JP, Zeanah CH. Factors affecting the diagnosis and prediction of PTSD symptomatology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:644–651. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH. Symptom expression and trauma variables in children under 48 months of age. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1995;16:259–270. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(199524)16:4<259::AID-IMHJ2280160403>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH. A relational perspective on PTSD in early childhood. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:799–815. doi: 10.1023/A:1013002507972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW. Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:899–906. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000169013.81536.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Huston L, Egeland B. Identification of child maltreatment using prospective and self-report methodologies: A comparison of maltreatment incidence and relation to later psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Yates TM, Egeland BR. The relation of emotional maltreatment to early adolescent competence: Developmental processes in a prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BW. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA. The development of the person. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg KJ, Baradaran LP, Abbott CB, Lamb ME, Guterman E. Type of violence, age, and gender differences in the effects of family violence on children’s behavior problems: A mega-analysis. Developmental Review. 2006;26:89–112. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2005.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Featherman DL. A revised socioeconomic index of occupational status. Social Science Research. 1981;10:364–395. doi: 10.1016/0049-089X(81)90011-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe VV, Brit JA. Child sexual abuse. In: Mash EJ, Terdal LG, editors. Assessment of childhood disorders. New York, NY: Guilford; 1997. pp. 569–626. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe VV, Gentile C, Michienzi T, Sas L, Wolfe DA. The Children’s Impact of Traumatic Events Scale: A measure of post-sexual-abuse PTSD symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:359–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe VV, Gentile C, Wolfe DA. The impact of sexual abuse on children: A PTSD formulation. Behavior Therapy. 1989;20:215–228. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80070-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Dodds MF, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Exposure to partner violence and child behavior problems: A prospective study controlling for child-directed abuse and neglect, child cognitive ability, socioeconomic status, and life stress. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:199–218. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000117. doi:10.1017.S0954579403000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]