Abstract

Caloric restriction (CR) has been shown to cause tumor regression in models of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), and the regression is augmented when coupled with ionizing radiation (IR). In this study, we sought to determine if the molecular interaction between CR and IR could be mediated by microRNA (miR). miR arrays revealed 3 miRs in the miR-17~92 cluster as most significantly down regulated when CR is combined with IR. In vivo, CR and IR down regulated miR-17/20 in 2 TNBC models. To elucidate the mechanism by which this cluster regulates the response to CR, cDNA arrays were performed and the top 5 statistically significant gene ontology terms with high fold changes were all associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) and metastases. In silico analysis revealed 4 potential targets of the miR-17~92 cluster related to ECM: collagen 4 alpha 3, laminin alpha 3, and metallopeptidase inhibitors 2 and 3, which were confirmed by luciferase assays. The overexpression or silencing of miR-17/20a demonstrated that those miRs directly affected the ECM proteins. Furthermore, we found that CR-mediated inhibition of miR-17/20a can regulate the expression of ECM proteins. Functionally, we demonstrate that CR decreases the metastatic potential of cells which further demonstrates the importance of the ECM. In conclusion, CR can be used as a potential treatment for cancer because it may alter many molecular targets concurrently and decrease metastatic potential for TNBC.

Keywords: Caloric restriction, Triple-negative breast cancer, microRNA, miR-17~92 cluster, Radiation

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) account for almost 20 % of breast malignancies and are defined by a lack of hormone receptors, an aggressive nature, and poor prognosis, including high recurrence rates with short intervals to recurrence [1, 2]. Several anticancer agents including ionizing radiation (IR) are routinely used to treat TNBC patients, but the reported benefits from this therapeutic modality are inconsistent and incompletely defined [3]. Although many of these patients respond well to the standard therapies, the subset that do not respond have early recurrences or may not respond to initial treatment at all [4, 5]. Therefore, the molecular underpinnings of TNBC are currently being evaluated to identify novel therapeutic targets that may increase response to treatment to ultimately improve the tumor response and the overall outcomes of our current standard treatments [6, 7]. Increasing and improving the treatment response in TNBC might be achieved by augmenting the standard treatment protocols with novel therapies [8–10]. In this context, several recent studies have shown that combining two inhibitors against the same molecular target may be beneficial [11, 12]. However, further studies may be limited by overlapping toxicity profiles of the agents. Hence, employing a more global process that may significantly decrease the activity of multiple parts of critical signaling pathways might be an alternative approach. Caloric restriction (CR) in the form of reducing food intake by nearly 20–30 % is one such method to achieve this. CR has already been shown to induce changes in multiple parts of molecular pathways without toxicity, making it an attractive modality to explore [13–16].

We have previously demonstrated that CR in combination with IR causes an additive tumor regression in two in vivo models of TNBC [17]. In the current work, we sought to determine if the molecular interaction between CR and IR could be mediated by microRNAs (miRs). Using miR profiling, we found the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster to be decreased with CR and IR, and it was even further down regulated by the combination. In turn, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins were noted to be upregulated; and functionally we observed decreased metastatic potential when the miR-17~92 cluster was down regulated. Taken together, this suggests that the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster could be used as a target for the treatment of TNBC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and ionizing radiation

Human TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells and mouse TNBC 4T1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA) at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 in humidified air. To mimic CR, DMEM with 4.5 g/L glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate was mixed with either 35 % or 70 % of DMEM without glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (cata-log#10-013 and 17-027-cv, Corning, NY). A PanTak 320 kVp X-RAD (Pantak, CT) was used for IR treatment. We used a 6 Gy dose to irradiate cancer cells in vitro and an 8 Gy dose for mouse tumors.

Orthotopic mammary transplant and tumorigenesis assays

Forty female Balb/c mice (ages 11–13 weeks) were obtained according to our protocol approved by the Thomas Jefferson University IACUC. To evaluate the effect of caloric restriction on metastatic growth, we randomized mice into 4 treatment groups: (1) controls with an ad libitum diet (AL), (2) radiation to the primary tumor (8 Gy dose IR), (3) 30 % reduction in caloric intake (CR), or (4) a combination of CR and IR. Before randomization, all mice were injected with 50,000 4T1 cells into the #4 mammary fat pad [17]. Once the tumor was palpable (5–7 mm), 10 mice were treated in each group. Ad libitum fed (AL) animals were given unrestricted access to standard NIH-31 mouse diet throughout the duration of the experiment. Average daily food intake per animal was determined for all groups by weighing food 2–3 times per week. Intake baseline was established at least 2 weeks prior to implantation and/or altering feeding protocol. A 30 % reduction in calories from their baseline intake was chosen because CR is defined as a reduction in overall calories between 20 and 40 % [17]. Each mouse in the CR groups received a 30 % reduction of their total NIH-31 diet which was supplemented with a soluble multivitamin (Trixie Vitamin Drops for Rabbits and Small Rodents, Trixie Pet Products, Inc. Fort Worth, TX) that was placed in their daily drinking water. Tumor volume was measured with calipers every 3 days. Mice were sacrificed when the tumors reached 1.8 cm3 or for humane endpoints. Tissue was collected and stored in RNAlater (Ambion, CA) or was snap frozen for future use.

miRNA microarray analysis

MicroRNAs microarray profiling was performed using total RNA extracted from three tumors from each of the four treatment groups: AL, CR, AL+IR, and CR+IR. miR microarray analysis was then done by LC Sciences (Houston, TX) as described by the manufacturer. Data were corrected by subtracting the background and normalized to the statistical median of all detectable transcripts. All differentially expressed transcripts with p value <0.05, were presented in log2 scale with a positive log2 value indicating an upregulation and a negative log2 indicating a down regulation.

Target analysis

An in silico search for potential miRNA targets was performed using targets that were evident in both of the following miRNA target prediction algorithms: TargetScan (release 6.2, http://www.targetscan.org) and miRNADA (http://www.mirorna.org).

3′UTR constructs, transfection, and Luciferase assay

As targets for miRs, we focused on the 3′ untranslated regions of mRNAs. Specifically, for 3′ untranslated region wild-type reporters for the ECM target proteins, we PCR-amplified the conserved DNA sequences of the predominant ECM genes from human genomic DNA and cloned into a destabilized firefly luciferase p-MIR-report vector (Ambion, CA) to generate reporter constructs. The following PCR primer sets to test the ECM targets were used: COL4A1 WT sense 5′-GCACTAGTTCAATAGTGGCATACCAAATG-3′, COL4A1 WT antisense 5′-GCAAGCTTACCTTGATCTGCCTAATTGCTGAC-3′; collagen 4 alpha 3 (COL4A3) WT sense 5′-GCACTAGTGTCAGTTCTGTGATCTGGGTCT-3′, COL4A 3-2 WT antisense 5′-GCAAGCTTTAGTACAGTGCCTGGGACATGCTT-3′; LAMA3 WT sense 5′-GCACTAGTCCCAAGCCTATTTCACAG-3′, LAMA3 WT antisense 5′-GCAAGCTTAAGGACTACACTGCA-3′; and TIMP2-3 WT sense 5′-GCACTAGTAATGCTTCCAAAGCCACCTTAGCC-3′, TIMP2 WT antisense 5′-GCAAGCTTTAAAGGCCACACCTTTCAGACCGA-3′. For ECM-3’UTR MUT reporters, the 55-bp conserved elements with different seed sequences to simulate mutants, such as TIMP2 MUT sense 5′-CTAGTCCTTGGTAGGTATTAGACTTGCGCGTGTTTAAAAAAAGGTTTCTA-3′ and TIMP2 MUT antisense 5′-A GCTTAGAAACCTTTTTTTAAACACGCGCAAGTCTA-ATA CCTACCAAGGA-3′, were cloned into a destabilized firefly luciferase p-MIR-report vector. The mutated nucleotides were underlined. For all sense and antisense primers, the Spe restriction site (ACTAGT) and HindIII restriction site (AAGCTT) were added, respectively. We transfected HEK293 cells with 20 ng of each of the reporter constructs, and 10 ng of Renilla luciferase internal control vector, along with pre-miR-17, pre-miR-20a, or negative control (NC) oligomers using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA) in 96-well plates. After 48 h, Dual-Glo reporter assays were performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, CA). To generate ectopic expression or silencing of miR-17 or miR-20a, 50 nM of precursor miRNA or antisense oligomers (Ambion, CA) were transiently transfected into 4T1 or MDA-MB-231 cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h, total RNA and protein lysates were collected for use, respectively, in qPCR or Western blotting assays.

Western blot analysis

Total protein lysates were generated from TNBC cells using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % NP40, 0.25 % sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF), 1 tablet of mini protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and 1x phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated on 4–12 % Bis–Tris precast gels (Invitrogen, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Heathcare, Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were blocked using 5 % nonfat dry milk, probed with the appropriate primary antibody and either rabbit anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Santa Cruz, CA). Protein detection was done using ECL solution (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) (TIMP2; ab1828, TIMP3; ab39184) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO) (Tubulin; T8328). The ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov) was used to quantify the western blot data.

Scratch wound healing assay and transwell cell invasion assay

4T1 cells were cultured as monolayers in either full DMEM or CR medium (70 and 35 %) or transfected with NC or anti-sense-miR-17/20a oligomers using 6-well plates. A single stripe (150 µm wide) was scraped on a cell-coated surface with a 200-µL disposable plastic pipette tip. The scrape wound was allowed to heal for 24 h at 37 °C. The average extent of wound closure was evaluated by measuring the width of the wound. Cell migration and cell invasion assays were done using transwell plates with or without Matrigel (BD Scientific, CA) pre-coating. 4T1 cells were either pre-incubated in CR medium or transfected with NC or miR-17 anti-oligomers for 24 h. Prior to plating cells in the upper chamber, the underside of each transwell was coated with fibronectin. 50,000 cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and plated onto the upper chamber of the transwell; 10 % serum-containing medium was added to the lower chamber. In cell invasion assays, the upper surface was also coated with Matrigel. At 48 h after incubation, cells that had migrated through the membrane were counted by 0.1 % crystal violet staining. The ratio of migrated cells to total cells was plotted.

RNA Purification and qRT-PCR

Total RNA, including small RNAs, was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Applied Biosystems, CA). RNA was evaluated for quality and quantified by absorbance spectra on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

qRT-PCR analysis of mature miRs was performed using the TaqMan kits with 10 ng total RNA to evaluate miR-17, 18a, 19a, 19b, and miR-20a according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, CA). The reverse transcriptase reaction was done by incubating samples at 16 °C for 30 min, 42 °C for 50 min, and 85 °C for 5 min. The PCR reaction (20 µL) contained 1.3 µL of reverse transcriptase product, 10 µL of TaqMan 2X Universal PCR Master Mix, and 1 µL of the appropriate TaqMan Micr-oRNA Assay (×20) containing primers and probes for the miR of interest. The PCR mixtures were incubated at 95 °C for 10 min and then put through 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. PCR was done in triplicate using an ABI 7500 Fast real-time PCR system.

To detect the level of ECM mRNAs, cDNA was prepared from 500 ng of total RNA using the High Capacity Synthesis System (Applied Biosystems, CA). The PCR reaction contained 1.3 µL of reverse transcriptase product, 10 µL of SYBR green 2× Universal PCR Master Mix, and 1 µL of the appropriate sense and antisense primers of interest. The following primer sequences were used for ECM and Actin amplification: Human LAMA3 sense 5′-AGC ACT TGC TGT GGA AAT CTG-3′, antisense 5′-ACA CCG TCC GGT ATA CAA GCC-3′; human COL4A1 sense 5′-TCG CCG GGT TCT GTA GGA TTG-3′, antisense 5′-GCC TGC TTG TCC TTT GTC ACC-3′; human COL4A3 sense 5′-CTG CAG CGA TTT ACC ACA ATG C-3′, antisense 5′-AGC TGG TGT TGA CAG CCA GTA T-3′; human TIMP2 sense 5′-AGG CTT AGT GTT CCC TCC CTC-3′, antisense 5′-TGA GTG TGT CAC CAA AGC CAC-3′; and human TIMP3 sense 5′-TCC TGC TAC TAC CTG CCT TGC-3′, antisense 5′-AGC CAG GGT AAC CGA AAT TGG-3′. The expression of miR-17-92 or ECM mRNA was based on the AACT method, using U6, sno202, or GAPDH as an internal control. The relative expression was generated using the equation 2−ΔΔCT

Statistical analyses

The ANOVA analysis was used to compare 4 groups: AL, AL+IR, CR, and CR+IR in miR array data. The cDNA array data were analyzed by GO-Elite [18]. The GO-Elite ranked each analyzed term according to a Z score. The z score was calculated using the expected value and standard deviation of the number of genes meeting the criterion on a pathway under a hypergeometric distribution along with 2,000 permutation. False discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P values are calculated using a Benjamini–Hochberg correction [19]. Fold change calculated by pairwise comparisons of the average of mean array value between AL and AL+IR, and CR and CR+IR. Results of RT-PCR, Lucif-erase assays, and scratch test are expressed as the mean ± SEM of biological replicates performed in three independent experiments. For comparisons between two groups, the two-tailed paired or unpaired t test was used. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

CR alters the expression of miR-17~92 cluster

In two in vivo models of TNBC, we have previously shown [17] that CR, administered concurrently with radiation, represses tumor growth in a more than additive manner. To determine if microRNAs (miRs) might be involved as regulators of this physiologic response, we assayed tissue from the different test conditions for expression of various microRNAs.

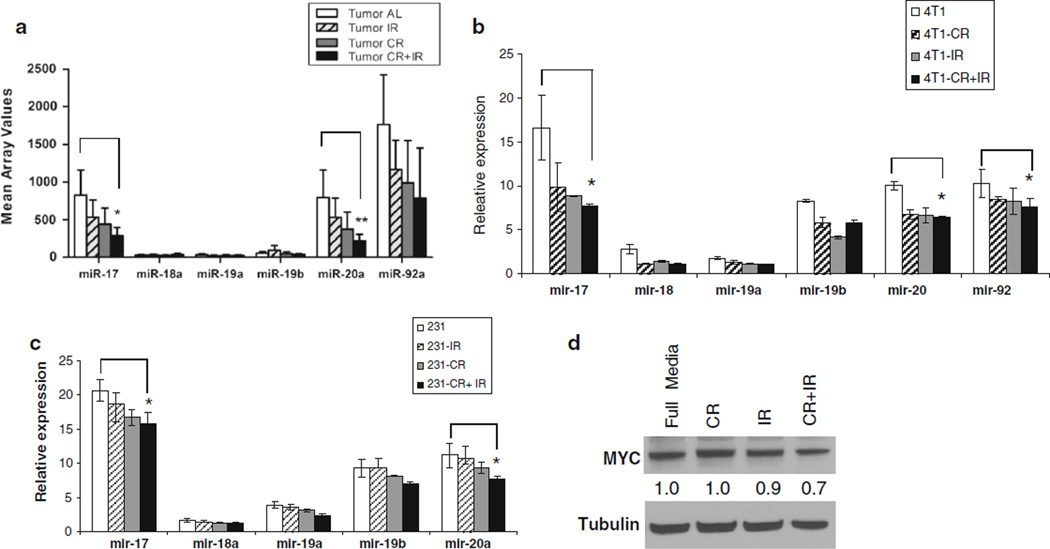

Results from this study revealed significantly decreased expression levels of both miR-17 and miR-20a when CR was combined with IR (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) compared with the control. The miR array mean values of all miRs in the miR-17~92 cluster are shown in Fig. 1a. Since this oncomiR cluster is noted to play an important role in defining TNBC [20], we sought to further characterize this cluster in the setting of CR. By modifying cell culture media with reduced glucose to mimic CR, cells were treated with four different conditions (control, IR, CR, and CR+IR) and revealed that CR caused a significant decrease in both miR-17 and miR-20a expression in 2 TNBC cell lines using qRT-PCR; 4T1 (Fig. 1b) and MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1c). This was even further reduced with the combination of CR and IR, which was consistent with our in vivo results. Since MYC is noted to regulate the expression of the miR-17~92 cluster [21], we sought to confirm this in our model; and western blots revealed that CR was able to decrease MYC expression as shown in Fig. 1d.

Table 1.

Microarray analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs in TNBC in vivo model with different treatments

| IR/ Control |

CR/ Control |

CR + IR/ Control |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mmu-miR-100 | 0.975657 | 0.522801 | 0.208314 | 0.0005 |

| mmu-miR-125b-5p | 0.946517 | 0.630466 | 0.436416 | 0.0146 |

| mmu-let-7i | 0.885899 | 0.522112 | 0.352236 | 0.0034 |

| mmu-miR-151-5p | 0.870721 | 0.431653 | 0.644348 | 0.0322 |

| mmu-miR-24 | 0.838282 | 0.634438 | 0.464685 | 0.0222 |

| mmu-miR-25 | 0.681604 | 0.544782 | 0.478387 | 0.03 |

| mmu-miR-20a | 0.666345 | 0.468864 | 0.277192 | 0.0063 |

| mmu-miR-17 | 0.644952 | 0.53243 | 0.350263 | 0.0034 |

| mmu-miR-99b | 0.601461 | 0.415815 | 0.606936 | 0.0293 |

| mmu-miR-709 | 0.588638 | 0.593461 | 0.513855 | 0.001 |

| mmu-miR-191 | 0.544377 | 0.365457 | 0.386146 | 0.0181 |

| mmu-miR-222 | 0.48094 | 0.542626 | 0.719579 | 0.0154 |

| mmu-miR-132 | 0.31291 | 0.260862 | 0.151206 | 0.0109 |

| mmu-miR-133b-3p | 0.166999 | 0.196337 | 0.21391 | 0.002 |

| mmu-miR-341-3p | 0.157701 | 0.193672 | 0.19551 | 0.0085 |

The ANOVA analysis was used to compare 4 groups; AL, AL+IR, CR, and CR+IR

Fig. 1.

CR reduces the expression of the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster in TNBC cell lines, a Tumors were generated in vivo using 4T1 cells and were treated with 4 different conditions: ad libitum feeding (AL), radiation (IR), caloric restriction (CR), and IR+CR. Three tumors from each condition were sent for miR arrays and mean array values for members of the miR-17~92 cluster are plotted with miR-17 and miR-20a having significantly changed values. To confirm the down regulation seen in vivo, in vitro studies were done with b 4T1 cells and c MDA-MB231 cells, which were cultured using four different conditions: (1) control (normal glucose), (2) IR, (3) CR (glucose reduced to 70 %), and (4) CR+IR. After 24 h, total RNA was extracted and qPCR revealed significantly decreased expression of miR-17 and miR-20a, which is consistent with array results from the in vivo tumor samples, d Since this cluster is known to be regulated by c-Myc protein, Western blots for c-Myc protein were done for all in vitro conditions. The results showed that c-Myc levels were reduced in CR+IR compared to the other conditions, just as the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster levels were. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

miR-17-92 targets ECM molecules

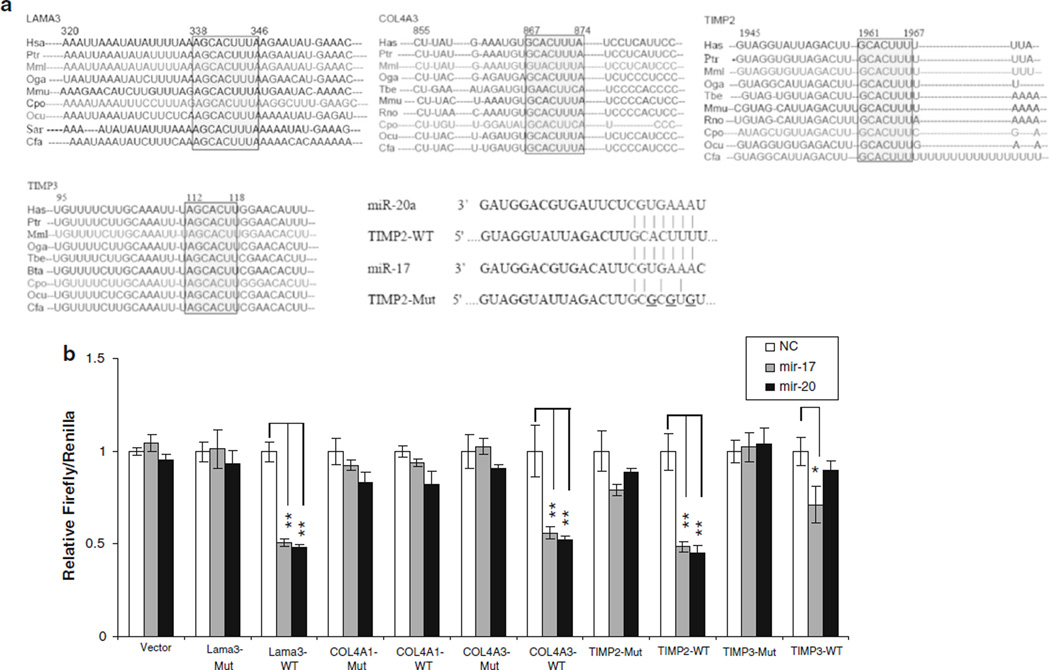

To determine the possible mechanisms by which the combination of CR and IR might be working in concert to induce tumor regression, cDNA arrays were performed. Gene ontology (GO) terms that were significantly over represented (permuted p value <0.01) were associated with ECM and metastases. Adjusted FDR P value of Collagen (GO: 0005581), Extracellular matrix structural constituent (GO: 0005201), and Basement membrane (GO: 0005604) are less than 0.25 (Table 2). Therefore, an in silico analysis was performed to find potential targets of the miR-17 family that could explain altered expression of ECM components. These were noted to include collagen 4 alpha 1 (COL4A1), COL4A3, laminin alpha 3 (LAMA3), and metallopeptidase inhibitors 2 and 3 (TIMP2 and TIMP3). Computer algorithms predicted that the 3′UTR of COL4A3, LAMA3, TIMP2, and TIMP3 contained regions matching the seed sequences of miR-17 and miR-20a, which were conserved across many species including humans, mice, rats, rabbits, and dogs (Fig. 2a).

Table 2.

Gene MAP pathway profile analyzed by GO-Elite

| AL vs CR+IR | GO name (GOID) | Z scorea | AVG-log fold changeb |

Permuted P value |

Adjusted permuted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen (GO:0005581) | 5.3 | 1.92 | < 0.001 | 0.114 | |

| Extracellular matrix structural constituent (GO:0005201) | 5.2 | 1.84 | < 0.001 | 0.114 | |

| Collagen biosynthetic process (GO:0032964) | 3.2 | 1.66 | 0.0095 | 0.724 | |

| Basement membrane (GO:0005604) | 3.3 | 1.64 | 0.0015 | 0.241 |

The Z score compares related Ontology terms based on their relative over representation Z score, which is an indicator of degree of over representation

Fold change calculated by pairwise comparisons of the average of mean array value between AL and CR + IR

Fig. 2.

miR-17 and miR-20a target ECM proteins. In silico analysis a of the miR-17 target sites revealed that LAMA3, COL4A3, TIMP2, and TIMP3 3’-UTRs are highly conserved among many species. To confirm that these proteins were in fact targets, b part of their 3′ UTRs containing the putative binding sites for miR-17 and 20a were cloned into luciferase reporters. Co-transfection assays with pTh-Renilla into HEK293 cells show that miR-17 and 20a can inhibit translation of a reporter gene containing a partial 3′ UTR of LAMA3, COL4A3, TIMP2; and miR-17 can regulate TIMP3. Mutants with altered binding sites were also used and did not show the same regulation, supporting the idea that miR-17 and 20a directly inhibit translation through interaction with elements in the 3′ UTRs of LAMA3, COL4A3, TIMP2; and miR-17 of TIMP3. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

To verify that mRNAs for these ECM proteins were targets of the miR-17 cluster, we generated the 3′UTR wild-type or mutant luciferase reporter constructs and analyzed their luciferase activity when tested against miR-17 and miR-20a. The 3′UTR luciferase reporter activities of LAMA3, COL4A3, TIMP2, and TIMP3 were each inhibited by miR-17 and miR-20a, but COL4A1 did not have this relationship (Fig. 2b) revealing that all the mRNAs except COL4A1 were indeed targets of miR-17 and miR-20a. The mutation of the miR-17 binding site in ECM 3′UTR abrogated this repression, supporting the idea that the effect of miR-17 or miR-20a is exerted through direct binding with the mRNA targets.

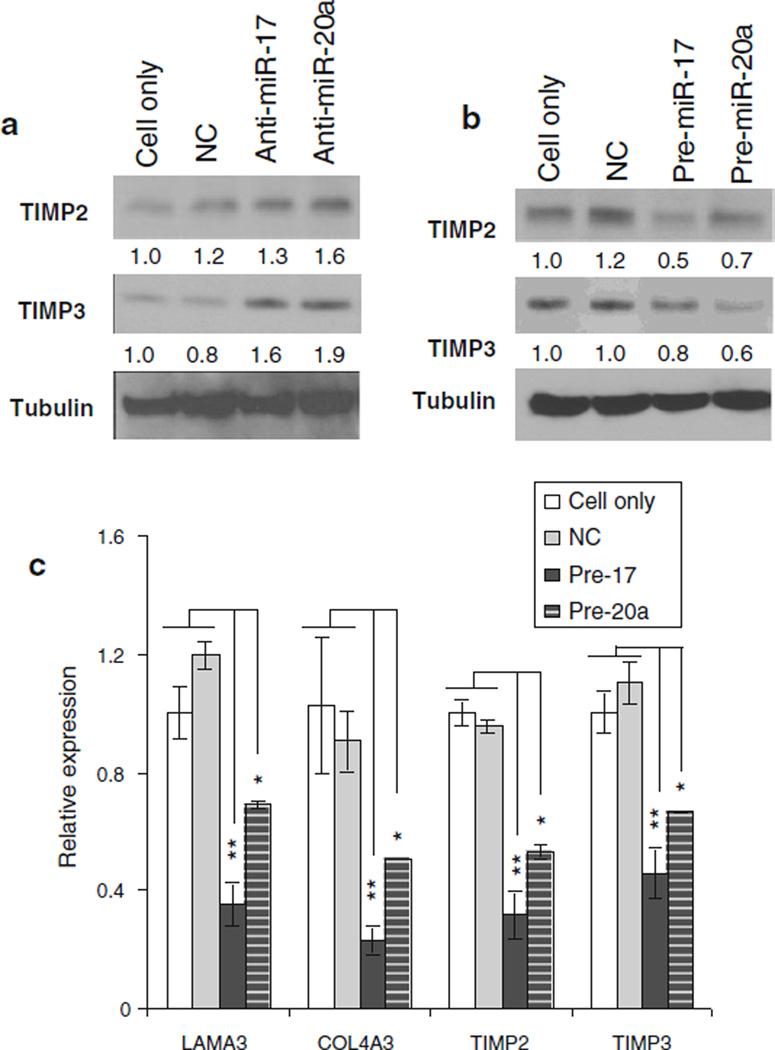

miR-17 or 20a suppresses the expression of ECM proteins

To further evaluate the relationship between miR-17 or miR-20a and the endogenous expression of ECM proteins, we evaluated the ECM protein levels after inducing ectopic expression of miR-17/20a with precursor oligomers and after inhibition with antisense oligomers. To evaluate the transfection efficiency of the precursor and antisense, the expression of miR-17 or miR-20a was evaluated (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3a, silencing miR-17/20a enhanced endogenous LAMA3, COL4A3, TIMP2, and TIMP3 expression, while miR-17/20a overexpression inhibited their expression (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3.

miR-17 regulates endogenous expression of ECM proteins. Inhibition of miR-17 and 20a using transient transfection of a anti-sense oligomers, and b overexpression with miR precursors and negative controls (NC) were measured. The results demonstrated the control of the miRs on TIMP expression at the protein level. In addition, c qPCR revealed decreased expression of the ECM genes in RNA extracted from transfected cells. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

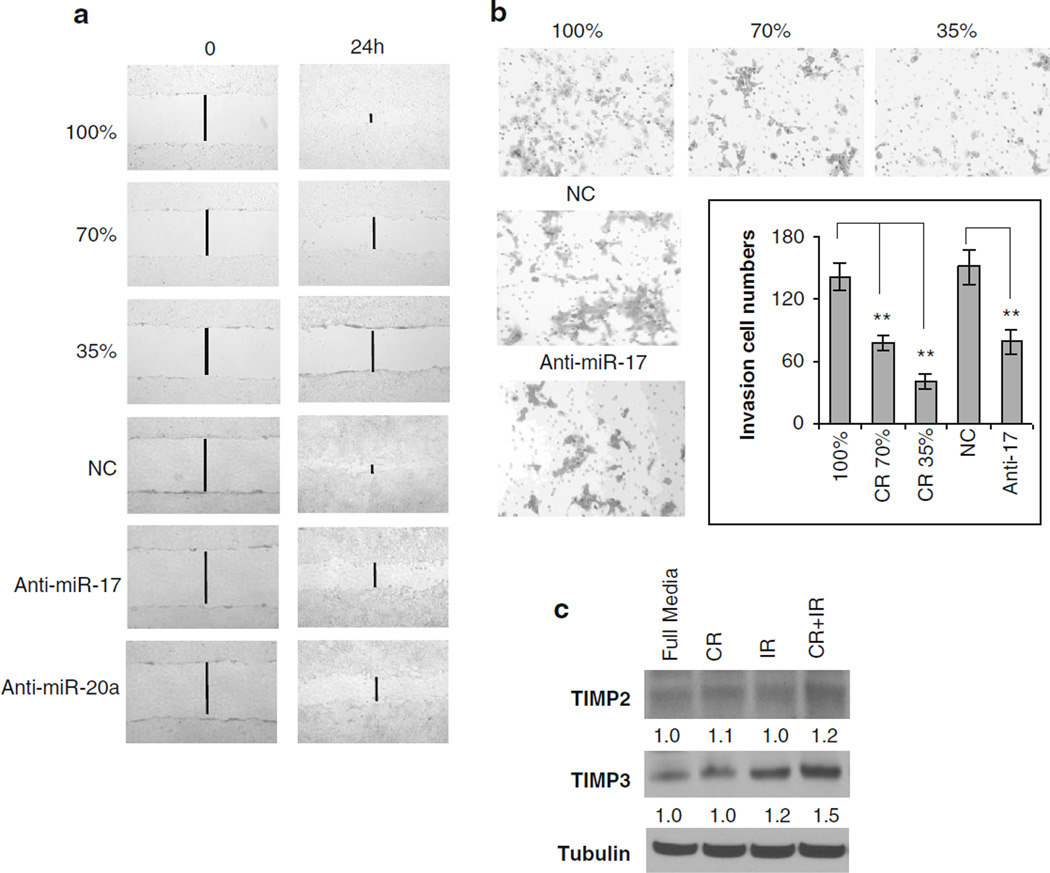

CR reduces migration and invasion by regulating TIMP2 and TIMP3

To determine if CR-mediated inhibition of miR-17/20a could decrease tumor metastases by restoring the expression of ECM proteins, transwell and scratch wound healing assays were employed. In both assays, migration was significantly reduced in CR treatment conditions compared with the full media (Fig. 4a, b, top panel). Transient transfection of the cells with an anti-sense-miR-17 or antisense-miR-20a oligomer demonstrated a decrease in migration and invasion potential that is similar to that of the CR condition (Fig. 4a, b, bottom panel). Since miR-17/ 20a regulates the expression of TIMP2 and TIMP3, we sought to determine if CR-mediated inhibition of miR-17/ 20a could regulate the expression of ECM proteins. TIMP2 and TIMP3 were in fact upregulated by CR with an even further increase with CR and IR (Fig. 4c). Taken together, these finding are consistent with the idea that CR can impact on the metastatic process.

Fig. 4.

CR decreases migration and invasion by regulating ECM. After exposing 4T1 cells to media with decreasing concentrations of glucose or transfection with anti-sense-miR-17/20a or NC oligomers, scratch wound tests were performed (a), which revealed fewer cells migrating into the wound at 24 h with dose-dependent CR conditioned media compared with control media, suggesting that CR decreases the migratory potential of TNBC cells. The same result was noted in anti-sense-miR-17/20a. To assess properties of invasion after exposure to CR and IR. b Matrigel-precoated transwells were used. Representative images demonstrated fewer invasive cells upon exposure to decreasing levels of glucose. Transient transfection of the cells with an anti-sense-miR-17 oligomer caused a decrease in invasion potential that is similar to that seen upon CR. By contrast, treatment with a negative control (NC) antisense oligomer had no effect. Representative images are shown. The graph illustrates comparable results by cell number. ** P ≤ 0.01. c After the cells had 24 h of exposure to (1) normal glucose medium, (2) 6 Gy IR, (3) CR, and (4) CR+IR, Western blots were performed, displaying the greatest increase in expression of TIMP2 and TIMP3 with the CR+IR condition

Discussion

Our prior in vivo study demonstrated that radiation, combined with the dietary modification of caloric restriction, can induce tumor regression and increase survival in models of TNBC [17]. Therefore, we sought to determine if miRs were responsible for the augmented response noted when CR is combined with radiation.

Arrays that looked at the relative abundance of different miRs demonstrated three miRs in the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster to be in the top ten of miRs that were significantly down regulated with the combination treatment: miR-17, 20a, and 92. This finding is consistent with the finding that the upregulation of the miR-17 ~ 92 oncomir cluster, including miR-17, miR-18a, miR-20a, and miR-92a, plays an important role in breast tumorigenesis and cell invasion [20, 22–24]. The oncogenic nature of this cluster is supported by the identification of miR-17-92 targets such as E2F1, p21, and BCL2L11/Bim, which have key roles in cell-cycle control and cell death [25–27]. Patients who develop metastasis are noted to have increased expression of miR-17 ~ 92 [20]. In addition, deep sequencing has demonstrated that increased expression of this cluster may in fact be characteristic of triple-negative breast cancer [22]. Since TNBC is the most aggressive breast cancer subtype with the shortest time to metastases and the worst prognosis, novel treatments and therapeutics are needed and might involve targeting of this cluster [28]. This cluster might also be useful in cancer treatment, given the finding that down regulation of miR-17 ~ 92 cluster occurred after both single-dose and fractionated radiation in prostate cancer cells [29].

Interestingly, in contrast to our findings about other miR members of this cluster, our dataset did not reveal a significant change in abundance of miR-19 with our treatments of CR or IR. This is consistent with a prior finding that relative abundance of miR-19 tends to vary independent of the rest of the cluster [30].

cDNA array analysis of our samples using GO-Elite revealed that the five most markedly changed GO terms with high fold increases were all associated with ECM. Consistent with this observation, other groups have reported that upregulation of the miR-17 ~ 92 cluster contributes to the promotion of metastases by targeting TGF-p signaling [31]. The TGF-p signaling pathway regulates the ECM and modulates cell invasion via the primary tumor microenvironment [32]. The invasiveness of cancer cells depends on the balance between deposition and proteolytic degradation of tumor ECM and the basement membrane [33]. We were able to demonstrate that CR increased the expression of important components of the ECM including TIMP2 and TIMP3, with an even further increase when CR was combined with IR. The upregulation of ECM by reduction of miR-17/20a could maintain the tissue homeostasis to prevent metastasis in TNBC with CR and IR. Our finding indicated that CR-mediated reduction of miR-17 ~ 92 cluster may play a key role in the inhibition of metastasis by regulating TGF-p signaling and remodeling ECM. In addition, at the functional level, we were able to demonstrate that CR decreases the metastatic potential of cells with both transwell and scratch wound healing assays. Therefore, CR could be an excellent adjuvant therapy for TNBC.

Therapeutic options for patients with TNBC have been limited, in part, due to the heterogeneity of molecular alterations in TNBC. This is particularly concerning for patients who are resistant to the conventional therapies [34]. However, one recent study reported successful inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in TNBC xenograft models using a triple-combination therapy involving an EGFR inhibitor, a PARP inhibitor, and chemotherapy [12]. While this approach is promising, combination therapy may lead to increased toxicity for patients due to the overlapping toxicity profiles of some of these therapies. Instead of targeting a few selected molecules, we have shown that CR can decrease the expression of many proteins simultaneously to inhibit cancer growth in an in vivo model of TNBC. Furthermore, our results now suggest that CR-mediated reduction of the miR-17~92 cluster may prevent metastasis by controlling the expression of ECM through a Myc-related pathway.

Our study has limitations, however, that should be considered. First, components of diet alone could impact miR expression. Although we believe that most changes are due to the overall stress of reducing calories, it could be that the nutrient density of the diet was not completely accounted for. Mice in the CR groups were supplemented with a soluble multivitamin but this would not be a complete match to account for the total nutrient density. Second, implementing a caloric restriction diet in cancer patients may be difficult due to the overall health status of the patient. Although we would expect early stage patients to be able to tolerate a continual 30 % reduction in calories during their radiation treatment, patients with advanced or metastatic disease may find this difficult to tolerate. One solution may be to achieve the same dietary-induced molecular changes with short-term fasting. Some reports have shown that exposure to a short-term starvation or fasting can protect normal cells from toxic effect of oxidative and chemotherapy drugs without causing chronic weight loss and can sensitize cancer cells by increasing DNA damage and apoptosis [35–38]. This suggests that short-term starvation or diet modification has the potential to enhance standard cancer therapies and may be implemented in the clinic as an overnight fast before receiving radiation therapy in the morning. Also, given that we were able to observe similar inhibition of an in vitro model of metastases with an anti-miR-17 oligomer, our results suggest that anti-miR-17 oligomers may prove useful in TNBC therapy.

Findings from this study suggest that the miR-17~92 cluster contributes to the response of TNBC to caloric restriction used in combination with radiation. Consequently, this cluster is worth investigating as a target or the basis of a therapeutic strategy for decreasing the metastatic potential of TNBC.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30-CA56036 for the Kimmel Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- CR

Caloric restriction

- IR

Radiation

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- miR

microRNA

- COL4A3

Collagen 4 alpha 3

- LAMA3

Laminin alpha 3

- TIMP2 and 3

Metallopeptidase inhibitors 2 and 3

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lianjin Jin, Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Meng Lim, Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Shuping Zhao, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Yuri Sano, Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Brittany A. Simone, Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA

Jason E. Savage, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Eric Wickstrom, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Thomas, Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Kevin Camphausen, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Richard G. Pestell, Department of Cancer Biology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA

Nicole L. Simone, Email: nicole.simone@jeffersonhospital.org, Department of Radiation Oncology, Thomas Jefferson University, Phiadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

References

- 1.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15):4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Aya LF, Chavez-MacGregor M, Lei X, Meric-Bern-stam F, Buchholz TA, Hsu L, Sahin AA, Do K-A, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Nodal status and clinical outcomes in a large cohort of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2628–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0388-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montagna E, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Cancello G, Iorfida M, Balduzzi A, Galimberti V, Veronesi P, Luini A, Pruneri G, Bottiglieri L, Mastropasqua MG, Goldhirsch A, Viale G, Colleoni M. Heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer: histologic subtyping to inform the outcome. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita T, Mizukami T, Okawara T, Inoue K, Fujimori M. Identification of a novel inhibitor of triple-negative breast cancer cell growth by screening of a small-molecule library. Breast Cancer. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger-Filho O, Tutt A, de Azambuja E, Saini KS, Viale G, Loi S, Bradbury I, Bliss JM, Azim HA, Ellis P, Di Leo A, Baselga J, Sotiriou C, Piccart-Gebhart M. Dissecting the heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1879–1887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan James S, Whittle Martin C, Nakamura K, Abell Amy N, Midland Alicia A, ZawistowskiJon S, Johnson Nancy L, Granger Deborah A, Jordan Nicole V, Darr David B, Usary J, Kuan P-F, Smalley David M, Major B, He X, Hoadley Katherine A, Zhou B, Sharpless Norman E, Perou Charles M, Kim William Y, Gomez Shawn M, Chen X, Jin J, Frye Stephen V, Earp HS, Graves Lee M, Johnson Gary L. Dynamic reprogramming of the ki-nome in response to targeted mek inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. 2012;149(2):307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yunokawa M, Koizumi F, Kitamura Y, Katanasaka Y, Okamoto N, Kodaira M, Yonemori K, Shimizu C, Ando M, Masutomi K, Yoshida T, Fujiwara Y, Tamura K. Efficacy of everolimus, a novel mTOR inhibitor, against basal-like triple-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(9):1665–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H, Hedayati M, Hobbs RF, Shao C, Bruchertseifer F, Morgenstern A, DeWeese TL, Sgouros G. Targeting aberrant DNA double strand break repair in triple negative breast cancer with alpha particle emitter radiolabeled anti-EGFR antibody. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim YH, Garcia-Garcia C, Serra V, He L, Torres-Lockhart K, Prat A, Anton P, Cozar P, Guzman M, Grueso J, Rodriguez O, Calvo MT, Aura C, Diez O, Rubio IT, Perez J, Rodon J, Cortes J, Ellisen LW, Scaltriti M, Baselga J. PI3 K Inhibition Impairs BRCA1/2 Expression And Sensitizes BRCA-proficient triple-negative breast cancer to PARP inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(11):1036–1047. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ejeh F, Shi W, Miranda M, Simpson PT, Vargas AC, Song S, Wiegmans AP, Swarbrick A, Welm AL, Brown MP, Chenevix-Trench G, Lakhani SR, Khanna KK. Treatment of triple-negative breast cancer using anti-EGFR-directed radioimmuno-therapy combined with radiosensitizing chemotherapy and PARP inhibitor. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(6):913–921. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.111534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lorenzo MS, Baljinnyam E, Vatner DE, Abarzua P, Vatner SF, Rabson AB. Caloric restriction reduces growth of mammary tumors and metastases. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(9):1381–1387. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phoenix K, Vumbaca F, Fox M, Evans R, Claffey K. Dietary energy availability affects primary and metastatic breast cancer and metformin efficacy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(2):333–344. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0647-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2009;325(5937):201–204. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blagosklonny MV. Calorie restriction: decelerating mTOR-driven aging from cells to organisms (including humans) Cell Cycle. 2010;9(4):683–688. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saleh AD, Simone BA, Palazzo J, Savage JE, Sano Y, Dan T, Jin L, Champ CE, Zhao S, Lim M, Sotgia F, Camphausen K, Pestell RG, Mitchell JB, Lisanti MP, Simone NL. Caloric restriction augments radiation efficacy in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(12):8. doi: 10.4161/cc.25016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambon AC, Gaj S, Ho I, Hanspers K, Vranizan K, Evelo CT, Conklin BR, Pico AR, Salomonis N. GO-Elite: a flexible solution for pathway and ontology over-representation. Bioin-formatics. 2012;28(16):2209–2210. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiner A, Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Identifying differentially expressed genes using false discovery rate controlling procedures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(3):368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farazi TA, Horlings HM, ten Hoeve JJ, Mihailovic A, Halfwerk H, Morozov P, Brown M, Hafner M, Reyal F, van Kouwenhove M, Kreike B, Sie D, Hovestadt V, Wessels LFA, van de Vijver MJ, Tuschl T. MicroRNA sequence and expression analysis in breast tumors by deep sequencing. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4443–4453. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, Furth EE, Lee WM, Enders GH, Mendell JT, Thomas-Tik-honenko A. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38(9):1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v38/n9/suppinfo/ng1855_S1.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volinia S, Galasso M, Sana ME, Wise TF, Palatini J, Huebner K, Croce CM. Breast cancer signatures for invasiveness and prognosis defined by deep sequencing of microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(8):3024–3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu C-G, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(7):2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendell JT. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell. 2008;133(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435(7043):839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v435/n7043/suppinfo/nature03677_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivanovska I, Ball AS, Diaz RL, Magnus JF, Kibukawa M, Schelter JM, Kobayashi SV, Lim L, Burchard J, Jackson AL, Linsley PS, Cleary MA. MicroRNAs in the miR-106b family regulate p21/CDKN1A and promote cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(7):2167–2174. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01977-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molitoris JK, McColl KS, Distelhorst CW. Glucocorticoid-mediated repression of the oncogenic microRNA cluster miR-17-92 contributes to the induction of bim and initiation of apoptosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(3):409–420. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cascione L, Gasparini P, Lovat F, Carasi S, Pulvirenti A, Ferro A, Alder H, He G, Vecchione A, Croce CM, Shapiro CL, Huebner K. Integrated MicroRNA and mRNA signatures associated with survival in triple negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John-Aryankalayil M, Palayoor ST, Makinde AY, Cerna D, Si-mone CB, 2nd, Falduto MT, Magnuson SR, Coleman CN. Fractionated radiation alters oncomir and tumor suppressor miR-NAs in human prostate cancer cells. Radiat Res. 2012;178(3):105–117. doi: 10.1667/rr2703.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Yu H, Lou JR, Zheng J, Zhu H, Popescu N-I, Lupu F, Lind SE, Ding W-Q. MicroRNA-19 (miR-19) regulates tissue factor expression in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(2):1429–1435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dews M, Fox JL, Hultine S, Sundaram P, Wang W, Liu YY, Furth E, Enders GH, El-Deiry W, Schelter JM, Cleary MA, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. The myc-miR-17-92 axis blunts TGFβ signaling and production of multiple TGFβ-dependent antiangiogenic factors. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):8233–8246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curran CS, Keely PJ. Breast tumor and stromal cell responses to TGF-β and hypoxia in matrix deposition. Matrix Biol. 2013;32(2):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeClerck YA, Mercurio AM, Stack MS, Chapman HA, Zutter MM, Muschel RJ, Raz A, Matrisian LM, Sloane BF, Noel A, Hendrix MJ, Coussens L, Padarathsingh M. Proteases, extracellular matrix, and cancer: a workshop of the path B study section. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(4):1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, Cameron D, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(12):683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.154. http://www.nature.com/nrclinonc/journal/v7/n12/suppinfo/nrclinonc.2010.154_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C, Raffaghello L, Brandhorst S, Safdie FM, Bianchi G, Martin-Montalvo A, Pistoia V, Wei M, Hwang S, Merlino A, Emionite L, de Cabo R, Longo VD. Fasting cycles retard growth of tumors and sensitize a range of cancer cell types to chemotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(124):124ra127. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C, Safdie FM, Raffaghello L, Wei M, Madia F, Parrella E, Hwang D, Cohen P, Bianchi G, Longo VD. Reduced levels of IGF-I mediate differential protection of normal and cancer cells in response to fasting and improve chemotherapeutic index. Cancer Res. 2010;70(4):1564–1572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longo VD, Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE, Valentine JS, Gralla EB. Human Bcl-2 reverses survival defects in yeast lacking superoxide dismutase and delays death of wild-type yeast. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(7):1581–1588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei M, Fabrizio P, Hu J, Ge H, Cheng C, Li L, Longo VD. Life span extension by calorie restriction depends on Rim15 and transcription factors downstream of Ras/PKA, Tor, and Sch9. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(1):e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]