Abstract

Objectives

To study the association between markers of cardiomyocyte injury in ambulatory subjects and sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Background

The pathophysiology of SCD is complex but is believed to be associated with an abnormal cardiac substrate in most cases. The association between biomarkers of cardiomyocyte injury in ambulatory subjects and SCD has not been investigated.

Methods

Levels of cardiac Troponin T, a biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury, were measured by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT) in 4431 ambulatory participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study, a longitudinal community-based prospective cohort study. Serial measures were obtained in 3089 subjects. All deaths, including SCD, were adjudicated by a central events committee.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 13.1 years, 246 participants had SCD. Baseline levels of hsTnT were significantly associated with SCD [Hazard ratio (HR) for +1Log(hsTnT) 2.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.78–2.34]. This association persisted in covariate-adjusted Cox analyses accounting for baseline risk factors (HR 1.30, 95%CI 1.05–1.62), as well as for incident heart failure and myocardial infarction (HR 1.26, 95%CI 1.01–1.57). The population was also categorized into 3 groups based on baseline hsTnT levels and SCD risk [Fully-adjusted HRs 1.89 vs. 1.55 vs. 1 (reference group) for hsTnT≥12.10 vs. 5.01–12.09 vs. ≤5.00 pg/mL, respectively; Ptrend=0.005]. On serial measurements, change in hsTnT levels was also associated with SCD risk (Fully-adjusted HR for +1pg/ml per year increase from baseline 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.06).

Conclusions

The findings suggest an association between cardiomyocyte injury in ambulatory subjects and SCD risk beyond that of traditional risk factors.

Keywords: death, sudden, myocytes, general population

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a major public health problem. (1, 2) Over the past few decades, improvements in primary and secondary prevention measures have led to significant declines in cardiovascular mortality from coronary heart disease. (3, 4) However, the rates of SCD have declined to a lesser extent (5–8) which emphasizes the need for a better understanding of SCD epidemiology and risk factors.

The pathophysiology of SCD is complex, but it is generally believed that an abnormal cardiac substrate underlies most cases. (2, 9–11) The association of cardiomyocyte injury and SCD risk in the general population has not been studied to date. Such investigation could have been limited by the inability of conventional assays to detect very low levels of circulating troponins that would reflect subclinical cardiomyocyte damage.

A recently developed highly sensitive cardiac troponin T assay (12) has allowed detection of very low levels of circulating troponin, even in ambulatory asymptomatic subjects. (12, 13) This biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury has been found to be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including heart failure and cardiovascular mortality. (14–17)

We hypothesized that cardiomyocyte injury, assessed by measures of cardiac troponin T levels by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT), is associated with SCD risk beyond traditional risk factors. The study hypothesis was tested in a large prospectively followed community-based population.

Methods

Study population

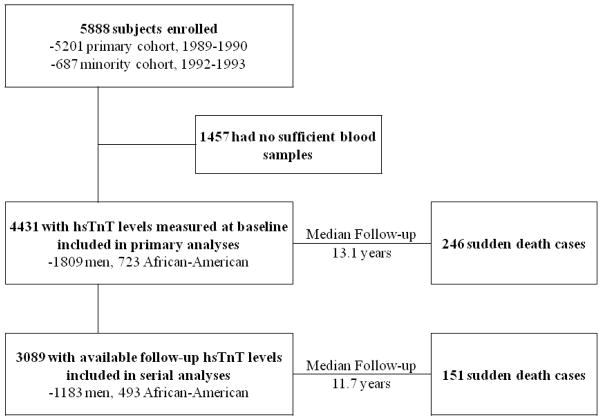

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a longitudinal study of adults aged 65 years or older at recruitment. The rationale, design and methods of CHS, including information on data collection and definition of comorbid conditions have been previously published. (18, 19) Briefly, the CHS population consisted of 5888 men and women recruited from Medicare files from 4 communities in the United States (Forsyth County, NC; Sacramento County, CA; Washington County, MD; and Pittsburgh, PA). The original cohort of participants included 5201 subjects who were enrolled from 1989 to 1990. A minority cohort was enrolled between 1992 and 1993, which included 687 African Americans. The cohort for current analysis included 4431 participants who had baseline levels of hsTnT from sera collected at enrollment. Of them, 3089 participants had follow-up measures (2–3 years after the original assay) and were included in analyses of the association between change in hsTnT levels and SCD risk (Figure 1). The CHS was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA) and participating sites. All subjects gave written informed consent at time of enrollment.

Figure 1. Enrollment and analysis flow of the study population.

hsTnT: Troponin T levels by highly sensitive assay.

Initial assessment, follow-up and cardiovascular events

At enrollment, study participants were assessed by a standardized questionnaire which addressed variable health and behavioral risk factors, in addition to a physical examination. (19–20) For each cardiovascular condition, self-reports were confirmed by components of the baseline examination or, if necessary, by a validation protocol that included either the review of medical records or surveys of treating physicians. (19) For instance, in addition to patient interview, the baseline examination sought to identify major Q waves or the combination of minor Q waves and ST-T-wave changes on electrocardiograms to confirm self-reported myocardial infarction (MI). Self-reported heart failure was confirmed by symptoms, physical signs and the use of both diuretics and either digitalis or a vasodilator. Further confirmation of MI or heart failure, was sought from treating physicians by questionnaire or from hospitals by discharge summaries, as well as by review of medical records. (19) Coronary heart disease was defined as a history of angina, coronary revascularization, or previous MI. After the initial assessment, enrolled subjects were contacted every 6 months for follow-up, alternating between telephone interviews and clinic visits through 1998–1999 and by telephone interviews only thereafter. All participants had resting 12-lead electrocardiograms obtained at baseline and these were repeated annually through the last clinic visit. Echocardiograms were obtained at baseline for the original cohort and at the study visit in 1994–1995 for both cohorts. In addition, discharge diagnoses for all hospitalizations were collected. New cardiovascular events, reported during a clinical visit, a telephone encounter or from a hospital stay were confirmed by obtaining medical records and adjudicated by a centralized events committee. (20) The details on ascertainment and adjudication of death and cardiovascular events, including incident heart failure and myocardial infarction, in CHS have been previously published. (20) Incident heart failure was confirmed by documentation in the medical record of a constellation of symptoms and physical signs with supporting clinical findings or a record of medical therapy for heart failure. Incident MI was confirmed by electrocardiographic criteria and measures of cardiac enzymes. (20) Information on death was obtained from reviews of medical records, death certificates, autopsy reports and coroners’ reports and ascertainment of death was 100%. Causes of death were assessed by additional review of inpatient, nursing home or hospice records, physician questionnaires and by interviews with next-of-kin. Autopsy reports were also reviewed when available. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as mortality related to atherosclerotic heart disease, mortality following cerebrovascular disease, or mortality from other atherosclerotic and cardiovascular diseases including heart failure. (20)

To identify SCD cases for the present study, all cases of fatal cardiovascular death were reviewed and adjudicated by physicians. SCD was defined as a sudden instantaneous pulseless condition, presumed to be from a malignant ventricular arrhythmia, in a previously stable individual without evidence of a non-cardiac cause of the arrest. We a priori sought to exclude cases with non-arrhythmic characteristics, including those with evidence of progressive hypotension or advanced congestive heart failure before death. All SCD events in this analysis occurred out of the hospital or in the emergency room. All deaths that occurred under hospice, nursing home care or in subjects with life-threatening non-cardiac comorbidities were not considered SCD. Available data from death certificates, informant interviews, physician questionnaires, coroner’s reports, and hospital discharge summaries were reviewed, as well as circumstances surrounding the event, to accurately classify whether the subject had experienced SCD. For non-witnessed deaths, the participant must have been seen within 24 hours of the arrest in a stable condition and without evidence of a non-cardiac cause of cardiac arrest. A blinded second physician review of a random sample of 70 of these death records showed an 88% inter-reviewer agreement and κ =0.74 for SCD.(21)

Cardiac Troponin T assays

Details on blood sample acquisition as well as analytical and quality-assurance methods in CHS were previously published. (22) All measurements of troponin T levels were performed in a central blood analysis laboratory. Baseline measures were obtained from sera collected at enrollment. Follow-up measures were performed on blood samples collected 2 to 3 years later. Blood samples were stored at −70ºC to −80ºC and thawed just prior to laboratory assays (maximum of 3 freeze-thaw cycles) in April 2010. All cardiac TnT concentrations were measured using highly sensitive TnT reagents on an Elecsys 2010 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). The analytical measurement range of the assay was 3 to 10 000 pg/mL with an analytical coefficient of variation (CV) of 10%. (12) Values of hsTnT that were below the threshold of detection were set to 2.99 for continuous analyses. The analytical sensitivity, specificity, interferences, and precision of the assay were previously validated. (12) The value at the 99th percentile cutoff from a healthy reference population was 13.5 pg/mL. (12) The hsTnT measurements for this study are from reagent lots not affected by the recent technical bulletin from Roche Diagnostics regarding calibration curves of the assay for some TnT prior reagent lots. (23) All technologists performing and recording the biomarker assay results were blinded to participants’ outcomes including SCD.

Statistical analyses

The risk of SCD as a function of baseline hsTnT levels was assessed in the overall population. Furthermore, the association of change in hsTnT level with SCD was assessed in a group of participants with serial measures. Plasma levels of hsTnT were analyzed both as continuous variables for which natural log transformed values were used, as well as categorized into 3 groups of low, intermediate and high risk based on their association with SCD. The characteristics of these groups were compared by using the Chi-square test for proportions, the analysis of variance method for normally distributed continuous variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP pro version 9.0 (SAS; NC, USA) and STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp; TX, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

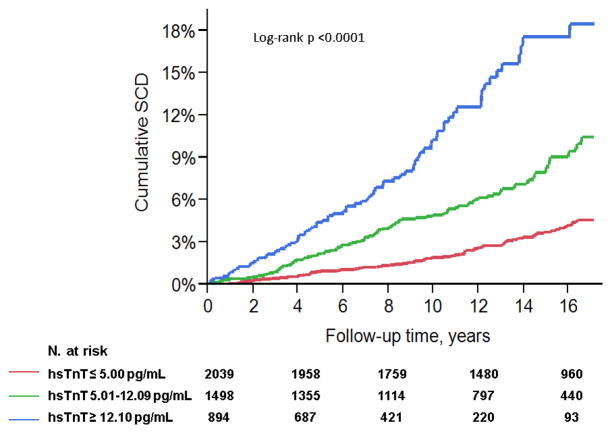

The study hypothesis of the association between hsTnT levels and SCD risk was first tested with hsTnT levels analyzed as a continuous variable. The 3 groups were subsequently identified by using Cox proportional hazards analyses of SCD risk in participants with undetectable levels of hsTnT (n=1442) and deciles of the population with detectable levels (n=2989) (Figure 2). The risk of SCD with increasing deciles of detectable hsTnT levels compared to participants with undetectable levels was employed to identify the low risk group. The cutoff was defined by the decile above which there was a statistically significant increase in SCD risk compared to participants in lower deciles and undetectable levels group. The high risk group was defined by evaluating SCD risk with descending deciles of detectable hsTnT levels compared to the 10th decile. The cutoff was defined by the decile below which there was a statistically significant decrease in SCD risk compared to participants in upper deciles. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to present cumulative SCD in the above defined groups (Log-rank test used for comparison).

Figure 2. Analysis performed to define low (≤ 5.00 pg/mL), intermediate (5.01–12.09 pg/mL) and high (≥ 12.10 pg/mL) risk categories of sudden cardiac death (SCD) based on Troponin T levels by a sensitive assay (hsTnT).

Figure shows hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of SCD with increasing deciles (D1 to D10) of detectable hsTnT levels compared to subjects with undetectable levels (≤2.99 pg/ml).

Covariate adjusted Cox models were employed to study the association of baseline hsTnT levels and SCD risk. The first set of multivariable analyses adjusted for demographics and baseline factors found to have a statistically significant relationship with SCD in univariate analyses. These factors included: age, race (African-American vs. not), gender, smoking (current vs. former vs. never), physical activity (log-transformed kilocalories per day), prior diagnoses of heart failure, coronary disease, MI, stroke or transient ischemic attack, ventricular conduction delay, Q and QS abnormalities, prolonged QT interval, qualitative left ventricular ejection fraction (<45% vs. 45–55% vs. >55%), left ventricular mass by electrocardiogram, systolic blood pressure, serum glucose levels, serum total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate (by the modified diet in renal disease formula), C-reactive protein (log-transformed), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (log-transformed), use of Aspirin, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics and digoxin. Further details about these covariates are included in Appendix 1. The second set of multivariable analyses additionally adjusted for incident heart failure and MI, in a time dependent analysis, to account for the well-established relationship between these conditions and SCD. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported from the proportional hazards models.

The association between change in hsTnT levels and SCD risk was evaluated in univariate and covariate adjusted Cox models as discussed above. The change in hsTnT levels was analyzed as a continuous variable of change per years between measurements from baseline and adjusted for baseline levels in multivariable models.

Finally, given that sudden and non-sudden cardiovascular deaths may have similar myocardial or coronary substrates, we provide parallel analyses with endpoints of all-cause mortality and non-sudden cardiovascular death.

Results

Based on the associations of deciles of hsTnT and SCD, hsTnT was categorized into three groups with cutoff points at 5.01 and 12.09 pg/mL. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the overall study population (n=4431) and by hsTnT category are summarized in Table 1. Participants were 72.8±5.6 years of age at enrollment (range 65–100), 40.8% were men, and 16.3% were African-Americans. Most of participants (91%) had preserved left ventricular function [ejection fraction (EF) >55%]. Overall, higher levels of hsTnT were associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease and risk factors (Table 1). There were 69 (3.4% of 2039), 99 (6.6% of 1498) and 78 (8.7% of 894) cases of SCD in the low, intermediate and high risk categories. The cumulative hazard of SCD by hsTnT category in the overall population is shown in Figure 3 (Log-rank test p-value <0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population (4431 participants from the Cardiovascular Health Study) categorized according to baseline levels of cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT).

| Characteristics | All subjects | hsTnT levels, pg/mL

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 5.00 | 5.01–12.09 | ≥ 12.10 | p-value | ||

| N | 4431 | 2039 | 1498 | 894 | |

| Age, years* | 72.8±5.6 | 70.9±4.2 | 73.5±5.4 | 76.2±6.6 | <0.0001 |

| Male gender | 40.8 | 25.3 | 47.9 | 64.3 | <0.0001 |

| Race, African American | 16.3 | 16.6 | 13.9 | 19.7 | 0.0009 |

| Current smoker | 10.9 | 12.7 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18.4 | 12.3 | 19.5 | 30.2 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, Kg/m2* | 26.8 ± 4.8 | 26.7±4.7 | 27.0±4.9 | 26.7±4.7 | 0.1 |

| Physical activity, Kcal/day† | 1031 (368–2243) | 1174 (450–2465) | 998 (349–2146) | 735 (245–1785) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 19.8 | 13.1 | 21.8 | 31.8 | <0.0001 |

| Prior MI | 9.6 | 5.9 | 10.0 | 17.3 | <0.0001 |

| Prior stroke | 3.9 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 8.6 | <0.0001 |

| Prior TIA | 3 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 5.7 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 45.3 | 38 | 49.5 | 54.8 | <0.0001 |

| LVEF | <0.0001 | ||||

| >55% | 90.9 | 95.2 | 90.8 | 81.1 | |

| 45–55% | 5.3 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 9.6 | |

| <45% | 3.8 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 9.3 | |

| VCD | 9.3 | 5.4 | 8.8 | 19.2 | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.8 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Long QT interval | 14.3 | 10.6 | 14.8 | 22.4 | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl† | 120 (92–164) | 119 (92–164) | 124 (93–163) | 118 (90–167) | 0.6 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl* | 54.2±15.8 | 56.8±15.7 | 52.7±15.3 | 50.9±15.9 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl* | 211.2±39 | 217.3±38.3 | 209.1±37.9 | 200.9±40.6 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dl* | 129.8±35.3 | 133.4±35.4 | 128.9±34.0 | 122.7±36.3 | <0.0001 |

| NT-pro BNP, ng/dl† | 115.9 (58.9–238.4) | 84.0 (44.6– 154.2) | 128 (66.2– 258.1) | 259.2 (11.5– 705.6) | <0.0001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L† | 2.6 (1.3–4.5) | 2.4 (1.2–4.3) | 2.4 (1.2–4.3) | 3.1 (1.6–7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Estimated GFR, SI units* | 78.2±23.5 | 83.3±21.4 | 77.5±23.1 | 67.6±24.9 | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl* | 112.8±39 | 107.6±32.8 | 113.4±34.9 | 123.9±53.6 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg* | 137±21.8 | 133.2±19.9 | 139.2±22.0 | 141.7±24.3 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg* | 70.8±11.3 | 70.3±10.6 | 71.0±11.5 | 71.5±12.5 | 0.02 |

| Aspirin | 34.3 | 32.1 | 35.9 | 36.5 | 0.02 |

| Antihypertensives | 48 | 40.5 | 51.5 | 60.1 | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 29.2 | 23.2 | 30.4 | 41.1 | <0.0001 |

| Beta blockers | 13.3 | 12.1 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 0.1 |

| ACE inhibitors | 7.8 | 5.4 | 9 | 11.3 | <0.0001 |

| Antiarrhythmics | |||||

| Class Ia | 2 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 | <0.0001 |

| Class Ib | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Class Ic | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Class III | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.04 |

| Digitalis | 8.7 | 3.7 | 9.8 | 18.5 | <0.0001 |

Numbers are percentages unless otherwise specified. MI: myocardial infarction. TIA: transient ischemic attack. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. VCD: Ventricular conduction delay. HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol. LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. BP: blood pressure. NT-pro BNP: N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. GFR: glomerular filtration rate. ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme.

mean±standard deviation,

median (interquartile range)

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Cumulative incidence of SCD in participants of the Cardiovascular Health Study (n=4431) based on baseline levels of Troponin T levels by a sensitive assay (hsTnT).

Over a median follow-up of 13.1 years (Interquartile range 7.8–16.3, maximum 17.1), 246 cases of SCD occurred in the overall population (5.6%). The unadjusted HR of SCD risk per Log hsTnT increase was 2.04 (95%CI 1.78–2.34, p<0.0001). This association persisted in covariate-adjusted Cox analyses which accounted for baseline demographics and risk factors (HR 1.30, 95%CI 1.05–1.62, p=0.02), as well as for incident heart failure and MI (HR 1.26, 95%CI 1.01–1.57, p=0.04).

The unadjusted HR for SCD in subjects with hsTnT levels in the intermediate and high risk groups compared to subjects with hsTnT levels lower than 5.00 pg/mL were 2.37 (95%CI 1.74–3.23) and 4.89 (95%CI 3.52–6.80), respectively (ptrend<0.0001). This association persisted in multivariable analyses (Table 2) adjusting for baseline demographics and risk factors [HRs 2.04 (95%CI 1.31–3.18) and 1.58 (95%CI 1.10–2.28) for baseline hsTnT levels ≥12.10 and. 5.01–12.09 respectively compared to ≤5.00 pg/mL, ptrend=0.001], as well as incident heart failure and MI [HRs 1.89 (95%CI 1.21–2.95) and 1.55 (95%CI 1.08–2.23) for baseline hsTnT levels ≥12.10 and 5.01–12.09 respectively compared to ≤5.00 pg/mL, ptrend=0.005].

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards analyses of sudden cardiac death (SCD) risk in Cardiovascular Health Study participants (n=4431) according to baseline levels of cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT).

| Univariate | Covariate-adjusted* | Covariate-adjusted** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| hsTnT levels | |||||||||

| ≤ 5.00pg/mL | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 | 1 | (reference) | 0.001 | 1 | (reference) | 0.005 |

| 5.01–12.09pg/mL | 2.37 | 1.74–3.23 | 1.58 | 1.10–2.28 | 1.55 | 1.08–2.23 | |||

| ≥ 12.10pg/mL | 4.89 | 3.52–6.80 | 2.04 | 1.31–3.18 | 1.89 | 1.21–2.95 | |||

| +1 Log hsTnT | 2.04 | 1.78–2.34 | <0.0001 | 1.3 | 1.05–1.62 | 0.02 | 1.26 | 1.01–1.57 | 0.04 |

HR: Hazard ratio. CI: confidence interval.

adjusted for demographics and baseline factors in association with SCD in univariate analyses: age, race (African-American vs. not), gender, smoking (current vs. former vs. never), physical activity, history of heart failure, coronary disease, history of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, ventricular conduction delay, Q and QS abnormalities, prolonged QT interval, left ventricular ejection fraction (<45% vs. 45–55% vs. >55%), left ventricular mass by electrocardiogram, systolic blood pressure, serum glucose levels, serum total cholesterol levels, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate by the modified diet in renal disease formula, C-reactive protein, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, use of Aspirin, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics and digoxin.

adjusted for the above as well as incident heart failure and myocardial infarction.

In subjects with serial levels of hsTnT (n=3089), 151 SCD cases (4.9%) occurred over a median follow-up of 11.7 years. In Cox proportional hazards analyses adjusting for baseline hsTnT levels, the HR of SCD for every 1 pg/mL per year increase from baseline was 1.05 (95%CI1.04–1.07, p<0.0001). This association persisted in multivariable analyses which additionally adjusted for demographics and risk factors (HR 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.06, p=0.02), as well as incident heart failure and MI (HR 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.06, p=0.03).

Finally, there was a significant association between baseline levels of hsTnT and the risk of all-cause mortality [HR for +1Log(hsTnT) 1.15, 95%CI 1.07–1.23, p=0.0001] and non-sudden cardiovascular death [HR for +1Log(hsTnT) 1.16, 95%CI 1.02–1.30, p=0.02] which persisted in covariate-adjusted models accounting for baseline risk factors, as well as incident MI and heart failure (Table 4). Similarly, these associations were also observed with analyses of serial measures and change of hsTnT levels from baseline (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards analyses of all-cause mortality and non-sudden cardiovascular death in Cardiovascular Health Study participants (n=4431) according to baseline and serial measures of cardiac troponin T by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT).

| Univariate | Covariate-adjusted* | Covariate-adjusted** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| All-cause mortality | |||||||||

| hsTnT levels | |||||||||

| ≤ 5.00 pg/mL | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 |

| 5.01–12.09 pg/mL | 1.79 | 1.63–1.97 | 1.19 | 1.08–1.32 | 1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | |||

| ≥ 12.10 pg/mL | 3.72 | 3.35–4.13 | 1.50 | 1.32–1.71 | 1.37 | 1.21–1.56 | |||

| +1 Log hsTnT | 1.90 | 1.81–1.99 | <0.0001 | 1.20 | 1.12–1.28 | <0.0001 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.23 | 0.0001 |

| hsTnT Change, +1 pg/mL/year | 1.05 | 1.05–1.06 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03 | <0.0001 |

| Non-sudden cardiovascular death | |||||||||

| hsTnT levels | |||||||||

| ≤ 5.00 pg/mL | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 | 1 | (reference) | <0.0001 | 1 | (reference) | 0.002 |

| 5.01–12.09 pg/mL | 2.34 | 1.96–2.80 | 1.40 | 1.16–1.69 | 1.26 | 1.04–1.52 | |||

| ≥ 12.10 pg/mL | 5.65 | 4.69–6.82 | 1.81 | 1.44–2.29 | 1.46 | 1.15–1.85 | |||

| +1 Log hsTnT | 2.22 | 2.06–2.39 | <0.0001 | 1.27 | 1.13–1.42 | 0.0001 | 1.16 | 1.02–1.30 | 0.02 |

| hsTnT Change, +1 pg/mL/year | 1.06 | 1.05–1.07 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.003 |

HR: Hazard ratio. CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

In a large community based population followed for up to 17 years, there was a significant graded association between cardiac troponin T levels measured by a highly sensitive assay and long term risk of SCD. The Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative SCD, based on hsTnT levels, separated very early after enrollment and continued to diverge throughout the duration of the study. The association between hsTnT levels and SCD risk persisted in covariate adjusted analyses accounting for an extensive number of risk factors including low ejection fraction, and incident heart failure and myocardial infarction suggesting that cardiomyocyte injury increases SCD risk beyond the effect of these covariates. Finally, there was a significant association between changes in hsTnT levels and SCD risk even after adjustment for covariates denoting a dynamic change in risk which can be assessed with serial measures.

The findings are novel and have significant clinical implications. Cardiac troponins are the preferred biomarkers for the diagnosis of acute MI. (24) Elevated levels of these biomarkers may also be observed in other acute clinical circumstances, in which myocardial injury may occur, and represent an indicator of poor outcomes. (25, 26) The prognostic value of such elevations has been also increasingly recognized in chronic cardiac conditions, such as stable coronary disease and heart failure. (27, 28) In the general population, detectable levels of cardiac troponins by conventional assays have been associated with structural heart disease (29) and increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events and cardiac mortality. (30–32) However, the detection thresholds of these assays have limited the application of such findings for clinical risk stratification purposes. (29)

The recently available hsTnT assay has allowed detection of much lower concentrations of circulating TnT, (12) and was found to have improved accuracy for the diagnosis of MI compared to conventional assays.(33)More recent studies have suggested that this assay may have potential beyond MI diagnosis and may provide important information regarding cardiovascular risk in various populations. (14–17)In patients with stable coronary disease and those with chronic heart failure, circulating hsTnT levels have been linked to cardiovascular mortality. (14, 15) In the general population, cardiac troponin levels by a highly sensitive assay were found to be associated with structural heart disease and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, (16, 17) but provided independent prognostic information regarding incident heart failure and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. (16, 17) The current study extends these observations to SCD risk in the general population of older adults. This population is of particular interest given that it contributes the most of SCD cases to the community. (2, 34, 35)

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the associations observed in this study deserve further investigation. It is possible that cardiomyocyte injury in ambulatory subjects results in myocardial scarring, providing an anatomical substrate for electrical reentry and lethal arrhythmias. Such injury could be related to aging, clinically recognized disease states, (16) or subclinical conditions such as unrecognized coronary disease. In fact, CAD underlies a significant subset of SCD cases. (2, 9) It is possible that many SCD victims develop myocardial ischemia prior to their collapse; but in contrast to those who present to the emergency rooms with acute coronary syndromes, SCD victims experience a sudden circulatory collapse; most commonly from a life threatening arrhythmia. The myocardial or coronary substrates of such events may be similar to those of non-sudden cardiovascular deaths. In fact, baseline and serial measures of hsTnT in this study were found as well to be associated with all-cause mortality and non-sudden cardiovascular deaths, suggesting an overlap in the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to sudden and non-sudden cardiovascular deaths. The HRs for SCD as a function of baseline hsTnT levels appeared to be higher than those for all-cause mortality and non-sudden cardiovascular death. The confidence intervals, however, overlapped which precludes definitive conclusions regarding strength of associations with SCD compared to all-cause and non-sudden cardiovascular mortality. Importantly, hsTnT levels were associated with SCD events which occurred up to 17 years after the initial assay. These observations, along with our observations of an association between change in hsTnT levels and SCD, suggest that cardiac troponin levels in ambulatory subjects may reflect an ongoing myocardial injury-remodeling process which may result in structural cardiac abnormalities that may in turn predispose to SCD. These explanations are, however, hypothetical and further research would be required to address the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Study limitations

The purpose of this paper was to study the association between cardiomyocyte injury assessed by hsTnT levels and the risk of SCD. The highlight was meant to be on the biological associations which help to better understand SCD. We did not aim to build a risk prediction model. Given the multifactorial nature of SCD and the complex pathology, no diagnostic test exists. The incidence of the outcome is relatively low and troponins are detected in a significant proportion of the population, which limits the use of this biomarker for diagnostic purposes. Nonetheless, a risk prediction model would require methods which are totally different than the methods employed in this manuscript. Also, the predictive value of hsTnT for SCD risk stratification purposes needs to be formally assessed and the findings need to be replicated in a different cohort before these could be applied in clinical practice.

The study has the inherent limitations of observational studies and the findings, therefore, may have been affected by residual confounding and do not establish causality. Also, no formal workup to rule out myocardial ischemia was performed and subclinical CAD could have been the underlying pathology. However, the associations persisted after adjusting for an extensive number of covariates and traditional risk factors that are usually assessed in clinical practice as well as incident heart failure and MI suggesting that cardiomyocyte injury may be involved in a pathophysiological process, which may lead to sudden death independent of these conditions. Another limitation was that blood samples were available for hsTnT assays in approximately 75% of the CHS population which could have introduced a bias in the overall estimates of SCD. This does not, however, negate the findings of significant association between these levels and SCD. The observations were made in a population of older adults and therefore may not be generalized to younger populations. Finally, there is no standard operational definition for SCD that has consistently been used across epidemiologic studies. Nonetheless, despite differences in populations, study designs, the availability of clinical data and the operational definitions used to classify SCD; the results of prior epidemiologic studies focusing on potential determinants of SCD typically have been consistent. In CHS, SCD was adjudicated from medical records and interviews with next of kin as to circumstances surrounding the event, and most cases did not have an autopsy and heart rhythm monitoring at time of sudden collapse. Misclassification of the outcome is possible, and would tend to underestimate the true association. Importantly, the operational definition used to define SCD in this report has been used in multiple previous studies (21, 36–42) from CHS; and the findings from these analyses have replicated findings from studies with other operational definitions of SCD. This reflects the fact that each of the operational definitions seek to identify persons who experience a life-threatening arrhythmia, ventricular fibrillation, that results in SCD in absence of successful resuscitation in the community.

In addition to novel observations, the study has several strengths including prospective design, relatively large population, inclusion of African-Americans, long-term follow-up, measures of hsTnT in a central lab and the adjudication of cardiovascular events by a central committee.

Conclusion

In a large community based population, there was an association between both baseline and change in cardiac troponin T when measured by a highly sensitive assay and SCD risk over long-term follow-up. This association persisted in covariate adjusted analyses which accounted for demographics, baseline risk factors, and incident heart failure and MI. The findings suggest an association between cardiomyocyte injury in ambulatory subjects and SCD risk beyond that of traditional risk factors.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards analyses of sudden cardiac death (SCD) risk in Cardiovascular Health Study participants (n=3089) according to serial change in troponin T levels measured by a highly sensitive assay (hsTnT)

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate-adjusted † | 1.05 | 1.04–1.07 | <0.0001 |

| Covariate-adjusted* | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.02 |

| Covariate-adjusted** | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.0303 |

Hazard ratios are for every 1 pg/mL per year increase from baseline.

adjusted for baseline hsTnT levels

, **please refer to Table 2 legends (additional adjustment for baseline hsTnT levels).

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This research was supported by NHLBI contracts HHSN268201200036C, N01-HC-85239, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086; N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133 and NHLBI grant HL080295, with additional contribution from NINDS. Additional support was provided through AG-023629, AG-15928, AG-20098, and AG-027058 from the NIA. See also http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

Abbreviations

- SCD

Sudden cardiac death

- hsTnT

Cardiac troponin T levels by a highly sensitive assay

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- HR

Hazard ratios

- CI

95% confidence intervals

Appendix 1. Other covariates. LV is left ventricular

| Variable | Methods |

|---|---|

| Physical activity | Assessed by using an instrument adapted from the Health Interview Survey which included a questionnaire about activities over a 2 week period. Siscovick et al. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997; 145 (11): 977–986. |

| Prior stroke | Adjudicated event. Self report confirmed by medical records. Ives e al. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–85. |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | Adjudicated event. Self report confirmed by medical records. Ives e al. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–85. |

| Ventricular conduction delay | Minnesota codes 7-1, 7-2 or 7-4 |

| Q and QS abnormalities | Minnesota codes 1-1 through 1–2 (except 1-2-8) |

| Prolonged QT interval | QT prolongation index QTI≥110%, with QTI=QT interval × (Heart rate + 100) /656 |

| LV ejection fraction | Qualitative assessment of left ventricular systolic function: Normal vs. borderline vs. abnormal (>55 vs. 45–55 vs. <45%) |

| LV mass by electrocardiogram | By using a model developed in CHS based on algorithms of the Novacode program. Rautaharju et al. Hypertension. 28(1):8–15. |

| Systolic blood pressure | Average of two separate readings |

| Antihypertensives | Use of any: Beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, diuretics, vasodilators, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin type 2 antagonists, or a combination of these. |

| Antiarrhythmics | Use of any class IA, IB, IC or III agents |

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr DeFilippi receives honorarium, consulting, and grant support from Roche Diagnostics and Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, and consulting and grant support from Critical Diagnostics and BG Medicine. Dr Dickfeld receives consulting and grant support from Biosense Webster and grant support from General electric. Drs Hussein, Gottdiener, Sotoodehnia, Deo, Siscovick, Stein, Lloyd-Jones and MsBartz have no relevant financial interests, activities, relationships or affiliations related to the content of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deo R, Albert CM. Epidemiology and genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2012;125:620–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:861–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox CS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Temporal trends in coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardiac death from 1950 to 1999: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2004;110:522–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136993.34344.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the united states, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001;104:2158–63. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudas K, Lappas G, Stewart S, Rosengren A. Trends in out-of-hospital deaths due to coronary heart disease in sweden (1991 to 2006) Circulation. 2011;123:46–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.964999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Frye RL, Weston SA, Killian JM, Roger VL. Secular trends in deaths from cardiovascular diseases: A 25-year community study. Circulation. 2006;113:2285–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myerburg RJ, Junttila MJ. Sudden cardiac death caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2012;125:1043–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zipes DP, Wellens HJ. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1998;98:2334–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubart M, Zipes DP. Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2305–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI26381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannitsis E, Kurz K, Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem. 2010;56:254–61. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.132654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latini R, Masson S, Anand IS, et al. Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:1242–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omland T, de Lemos JA, Sabatine MS, Christophi CA, Rice MM, Jablonski KA, Tjora S, Domanski MJ, Gersh BJ, Rouleau JL, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E Prevention of Events with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE) Trial Investigators. A sensitive cardiac troponin T assay in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2538–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304:2494–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Omland T, et al. Association of troponin T detected with a highly sensitive assay and cardiac structure and mortality risk in the general population. JAMA. 2010;304:2503–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The cardiovascular health study: Design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–76. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–7. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–85. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sotoodehnia N, Siscovick DS, Vatta M, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor genetic variants and risk of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2006;113:1842–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.582833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the cardiovascular health study. Clin Chem. 1995;41:264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apple FS, Jaffe AS. Clinical implications of a recent adjustment to the high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay: User beware. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1599–600. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.194985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/ non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline): A report of the american college of cardiology Foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:2022–60. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820f2f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, et al. Importance of cardiac troponins I and T in risk stratification of patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2002;106:1263–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028422.51668.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peacock WF, 4th, De Marco T, Fonarow GC, et al. Cardiac troponin and outcome in acute heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2117–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggers KM, Lagerqvist B, Venge P, Wallentin L, Lindahl B. Persistent cardiac troponin I elevation in stabilized patients after an episode of acute coronary syndrome predicts long-term mortality. Circulation. 2007;116:1907–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.708529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwich TB, Patel J, MacLellan WR, Fonarow GC. Cardiac troponin I is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality rates in advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:833–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084543.79097.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace TW, Abdullah SM, Drazner MH, et al. Prevalence and determinants of troponin T elevation in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113:1958–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniels LB, Laughlin GA, Clopton P, Maisel AS, Barrett-Connor E. Minimally elevated cardiac troponin T and elevated N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide predict mortality in older adults: Results from the rancho bernardo study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:450–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zethelius B, Johnston N, Venge P. Troponin I as a predictor of coronary heart disease and mortality in 70-year-old men: A community-based cohort study. Circulation. 2006;113:1071–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.570762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blankenberg S, Zeller T, Saarela O, et al. Contribution of 30 biomarkers to 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in 2 population cohorts: The MONICA, risk, genetics, archiving, and monograph (MORGAM) biomarker project. Circulation. 2010;121:2388–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kannel WB, Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Cobb J. Sudden coronary death in women. Am Heart J. 1998;136:205–12. doi: 10.1053/hj.1998.v136.90226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert CM, Chae CU, Grodstein F, et al. Prospective study of sudden cardiac death among women in the united states. Circulation. 2003;107:2096–101. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065223.21530.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Djousse L, Biggs ML, Ix JH, et al. Nonesterified fatty acids and risk of sudden cardiac death in older adults. Circ Arrhythm electrophysiol. 2012;5:273–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.967661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deo R, Katz R, Shlipak MG, et al. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and sudden cardiac death: Results from the cardiovascular health study. Hypertension. 2011;58:1021–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deo R, Sotoodehnia N, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and sudden cardiac death risk in the elderly. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:159–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.875369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemaitre RN, King IB, Mozaffarian D, et al. Plasma phospholipid trans fatty acids, fatal ischemic heart disease, and sudden cardiac death in older adults: The cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2006;114:209–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.620336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patton KK, Sotoodehnia N, DeFilippi C, Siscovick DS, Gottdiener JS, Kronmal RA. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is associated with sudden cardiac death risk: The cardiovascular health study. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Case LD, et al. Electrocardiographic and clinical predictors separating atherosclerotic sudden cardiac death from incident coronary heart disease. Heart. 2011;97:1597–601. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.215871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stein PK, Sanghavi D, Sotoodehnia N, Siscovick DS, Gottdiener J. Association of holter-based measures including T-wave alternans with risk of sudden cardiac death in the community-dwelling elderly: The cardiovascular health study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43:251–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]