Abstract

The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R; Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg, & Chauncey, 1989) measures four major aspects of borderline personality disorder (BPD): Affect, Cognition, Impulse Action Patterns, and Interpersonal Relationships. In the present study, 353 young adults completed the DIB-R at age 18 (Wave 1) and again two years later (Wave 2) at age 20. Concerning the prediction of future BPD features, three models were compared: (a) Wave 1 Affect scores predicting all Wave 2 BPD features (NA model); (b) Wave 1 Impulse Action Patterns scores predicting all Wave 2 BPD features (IMP model); and (c) both Wave 1 Affect and Impulse Action Patterns scores predicting all Wave 2 BPD features (NA-IMP model). Each model controlled for stabilities over time and within-time covariances. Results indicated that the NA model provided the best fit to the data, and improved model fit over a baseline stabilities model and the other models tested. However, even within the NA model there was some evidence that the impulsivity scores were not accounted for by other BPD features. These results suggest that although negative affect is predictive of most BPD symptoms, it does not fully predict future impulsive behavior.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is characterized by symptoms of severe mood disturbance, impulsive behaviors, inappropriate anger, self-harm behaviors, relationship problems, and identity disturbance (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Dimensional perspectives on BPD emphasize extreme variants of normal personality traits as the root of PD pathology (Trull & Durrett, 2005). The two BPD personality features receiving the most research attention are affective instability/negative affectivity and impulsivity/disinhibition (Skodol et al., 2002; Trull, 2001). Recent research has focused on determining whether one or both of these underlying personality traits may be responsible for the manifestation of other features of BPD (Tragesser, Solhan, Schwartz-Mette, & Trull, 2007). There are three leading perspectives on this issue. First, some suggest that affective instability (or emotion dysregulation) is the core feature of BPD (Linehan, 1993); others suggest that BPD is best conceptualized as an impulse control disorder (Zanarini, 1993; Bornovalova, Fishman, Strong, Kruglanski, & Lejuez, 2008). Finally, some conceptualize both impulsivity and affective instability as contributing independently to specific symptoms of BPD and combining to uniquely distinguish BPD from other disorders of affective or behavioral dysregulation (Siever & Davis, 1991; New & Siever, 2002).

Many researchers and clinicians assert that affective instability is the primary characteristic underlying other BPD features (e.g., Linehan, 1993). Affective instability is defined as frequent and intense fluctuations in negative emotional states, typically in response to environmental stimuli. Emotional dysregulation, or the inability to appropriately modulate these mood fluctuations, may perpetuate the individual’s distress and lead to additional intense expressions of affect, as well as cognitive distortions and poor decision-making (Linehan & Heard, 1992; Shedler & Westen, 2004). Further, affective instability is associated with more stable personality traits (e.g., neuroticism, negative affectivity) and is a common symptom of BPD, suggesting that it may have a role as a core feature that underlies the other symptoms of BPD. Theorists ascribing to this perspective argue, for example, that individuals with high levels of affective instability may become so emotionally dysregulated that their emotional states influence their cognitions (e.g., about self and others), thereby leading to identity problems and problems in interpersonal relationships.

From this perspective, impulsive behaviors, such as binge eating, substance use, and self-harm, are conceptualized as attempts to regulate or cope with negative emotional states (Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2002; Kullgren, 1988; Montgomery, Montgomery, Baldwin, & Green, 1989; Vollrath, Alnaes, & Torgersen, 1996; Yen, Zlotnick, & Costello, 2002). For example, Yen and colleagues (2004) found that affective instability was a stronger predictor of suicidal behavior than was trait impulsivity, and only affective instability was a significant predictor of suicide attempts. Affective instability is also one of the core features particularly associated with identity problems, certain interpersonal difficulties (Koenigsberg et al., 2001), and impulsive coping behaviors (Conklin, Bradley, & Westen, 2006). Buttressing this perspective, longitudinal research has found that affective instability tends to be stable over time (McGlashan et al., 2005), and the best predictor of questionnaire scores on self-harm, identity, and interpersonal problems over time (Tragesser et al., 2007).

Other theorists emphasize impulsivity or disinhibition as the core feature of BPD, and report that impulsivity can account for the other symptoms of BPD (e.g., Zanarini, 1993; Bornovalova et al., 2008). This perspective asserts that BPD is primarily an impulse-control disorder, sharing features with disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance use disorders, and antisocial personality disorder. According to this viewpoint, impulsive behavior and the negative consequences of such behavior (e.g., interpersonal conflicts) cause the unstable and intense emotional shifts exhibited in individuals with BPD (van Reekum, Links, Mitton, Federov, & Patrick, 1996). Supporting the centrality of impulsivity to BPD, Links, Heslegrave, and van Reekum (1999) found that impulsivity was the most stable BPD feature. Impulsivity was also the strongest predictor of overall levels of BPD pathology as well as prospective levels of affective and psychotic features. This finding is particularly noteworthy, suggesting that impulsivity, rather than affective instability, may be the major underlying feature of BPD. In addition, family history studies indicate that biological relatives of individuals with BPD are more likely to meet criteria for these other impulse control disorders (Zanarini, 1993) and to show higher levels of impulsivity, more generally (Links, Steiner, & Huxley, 1988). Finally, a great deal of research supports the links between impulsivity and a variety of problems with serotonergic and prefrontal cortex functioning, both associated with BPD (e.g., Oquendo & Mann, 2000; Soloff et al., 2003).

A third perspective emphasizes that the combination of affective instability/emotional reactivity and impulsive aggression leads to BPD symptoms (Siever & Davis, 1991; New & Siever, 2002). Additionally, proponents of this perspective suggest that the dual presence of affective instability and impulsivity uniquely distinguishes BPD from other disorders primarily characterized by either mood dysregulation (e.g., bipolar disorder) or impulsivity (e.g., antisocial personality disorder). Consistent with this perspective, family members of individuals with BPD tend to exhibit both of these traits (Silverman et al., 1991).

Findings supporting this perspective have been mixed. For example, Koenigsberg and colleagues (2001) evaluated the extent to which the combination of impulsive aggression and affective instability could predict the other core BPD features, hypothesizing that affective instability might result in a lack of consistency and disjointed personal experience, but that impulsivity might lead to inappropriate anger and interpersonal problems. Koenigsberg et al. (2001) found some support for these predictions, but relations between both affective instability and impulsive aggression and BPD features were not always consistent. Affective instability also predicted inappropriate anger and self-harm behaviors, while impulsivity also predicted affective instability criteria. Furthermore, this was a cross-sectional study, and therefore could not attest to which features best predicted changes in BPD features over time. Since Siever and Davis’ initial assertion, many other researchers have endorsed the idea that BPD is uniquely characterized by both strong negative affect and poor inhibitory control (Depue & Lezenweger, 2001; Nigg, Silk, Stavro, & Miller, 2005; Trull, 2001; Trull, Widiger, Lynam, & Costa, 2003). However, the relative contributions of these features to the disorder as a whole are not well-known and neither construct appears to fully account for the myriad of difficulties experienced by individuals with BPD. Thus, more research is needed to compare the roles of impulsivity and affective instability in BPD features.

Previously, Tragesser et al. (2007) tested three models that were relevant to these perspectives: (1) an affective instability (AI) model, in which scores on AI measures predicted BPD features at follow-up; (2) an impulsivity model, in which impulsivity scores predicted all BPD features at follow-up; and (3) an affective instability/impulsivity model, in which both AI and impulsivity scores predicted follow-up BPD features. Models were examined using a questionnaire-based measure of borderline features in a non-clinical sample, and results provided support for the affective instability model. Affective instability questionnaire scores were the best predictors of future impulsivity, negative relationships, and identity disturbance scores two years later.

The present study sought to replicate these analyses using an alternative measure of BPD features, the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R; Zanarini et al., 1989), which is commonly used in clinical samples and in longitudinal clinical research. The DIB-R includes separate assessments of specific BPD features and is structured in the form of four subsections: Affect, Cognition, Impulse Action Patterns, and Interpersonal Relationships. The DIB-R has also been shown to have good reliability (Zanarini, Frankenburg, & Vujanovic, 2002) and validity (Zanarini et al., 1989) in clinical samples. The DIB-R is frequently used to test the stability of the BPD diagnosis as well as its specific features and their interrelationships (Links et al., 1999; van Reekum et al., 1996; Links, Mitton, & Steiner, 1993; Zanarini, 1993; Zanarini, Frankenburg, & Vujanovic, 2002). Further, as a semi-structured interview, DIB-R assessments allow for follow-up questions, additional prompts, clarifications, and observations. Because these are not possible with a questionnaire-based assessment, some argue that the DIB-R provides a more comprehensive assessment of borderline features.

The longitudinal association between the DIB-R subscales has not been examined, however. Therefore, one goal of the present study was to determine which theoretical model best accounts for changes in BPD/DIB-R features over time. In a longitudinal sample including two waves of measurements separated by two years, three models were tested: (1) a negative affect model (NA model), in which Wave 1 Affect scores predicted all Wave 2 BPD/DIB-R features; (2) an impulsivity model (IMP model), in which Wave 1 Impulse Action Patterns scores predicted all Wave 2 BPD/DIB-R features; and (3) an affect/impulsivity model (NA IMP model), in which both Wave 1 Affect and Impulse Action Patterns scores predicted the Wave 2 BPD/DIB-R features.

It is worth noting that the DIB-R does not assess affective instability directly, but rather chronic negative affect, which may be a related but distinct construct (Conklin, Bradley, & Westen, 2006). Although negative affect is characteristic of many psychological disorders, the marked changes from baseline negative affect to extreme levels of anxiety, anger, irritability, and dysphoria are thought to be a unique characteristic of BPD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In other words, individuals with BPD experience both intense negative affect and AI. Thus, a second goal of the current study is to determine whether the results of Tragesser et al. (2007) could be replicated using a measure of chronic negative affect instead of affective instability per se.

A final goal of the present study was to examine the internal, test-retest, and inter-rater reliability estimates among the DIB-R scores in a large nonclinical sample with borderline features. Although previous research has examined DIB-R factor structure in nonclinical samples, reliabilities have not been extensively examined outside of a clinical population.

METHOD

Data were obtained from a sample of young adults enrolled in a longitudinal investigation of the development of borderline personality features (see Trull, 2001). The larger study involved screening approximately 5,000 18-year-old freshmen at the University of Missouri to identify individuals high and low in BPD features. Participants in the screening phase of the study were contacted through mailings, classes, telephone calls, and electronic messages (e-mails) and were scheduled to complete the screening battery during supervised sessions. All those who completed the screening received $5.00 or research credit if enrolled in Introduction to Psychology.

From the screening pool, individuals who scored ≥ 38 (above threshold; two standard deviations above the mean score for community participants) on the Personality Assessment Inventory—Borderline Features scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991) and those who scored below threshold (<38) were identified. From these groups of above- and below-threshold scorers in the screening sample, individuals were randomly selected to be recruited for participation in the laboratory phase of the study, and attempts were made to sample an approximately even number of men and women from each threshold group.

Multiple studies have indicated that an above threshold score on the PAI-BOR is associated with clinically significant borderline features (e.g., Morey, 1991; Trull, 1995; Trull, Useda, Conforti, & Doan, 1997). In a clinical sample, Kurtz and Morey (2001) found that PAI-BOR scores correlated .78 with a structured interview-based assessment of BPD. Further, a recent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis in a clinical sample comprised of 62 patients diagnosed with BPD and 45 patients with depressive disorders but no BPD produced an area under the curve (AUC) value of .78 (95% confidence interval: .70–.97) indicating good discrimination (Distel, Hottenga, Trull, & Boomsma, 2008).

Each person who agreed to participate in the laboratory phase of the study first completed the PAI-BOR a second time in order to ensure that the participant scored in the same range (i.e., above- or below-threshold) at retest. Participants were retested in order to exclude from the final sample those who produced state-like score elevations on the PAI-BOR. Participants in the first laboratory phase of the study (Wave 1) included over 400 young adults, approximately one-half of whom endorsed significant BPD features (see Trull, 2001 for full details). Two years later (Wave 2), a second laboratory assessment was conducted. The present study focuses on data collected at these two waves of laboratory data collection, Wave 1 (at age 18) and Wave 2 two years later (at age 20). From the 2 cohorts, 421 completed the laboratory phase of the study at Wave 1 (197 above-threshold; 224 below-threshold); 361 individuals (169 above-threshold; 192 below-threshold) participated at Wave 2. Of these 361 individuals, 353 had complete DIB-R data at both waves. Individuals did not participate in the Wave 2 data collection because they refused (n = 50), were unable to be located (n = 9), or were deceased (n = 1). Wave 2 participants did not differ from attriters on any measures of borderline features or criteria at Wave 1, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores at Wave 1, or by gender. There were also no significant differences between those who did and did not participate at Wave 2 concerning the Wave 1 number of criteria met for any Axis II disorder or Axis II cluster, or the Wave 1 lifetime diagnoses of alcohol or drug use disorders, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder.

All DIB-R interviewers underwent two months of training before collecting data for the study. The interviewers were unaware of the borderline features status (i.e., above-threshold vs. below-threshold) of the participants. At each wave of data collection, eighty participants who completed the DIB-R were randomly selected to assess the inter-rater reliability of interview scores. For each of these selected interviews, one of the remaining interviewers (randomly selected) reviewed the relevant portion of the videotape and provided independent ratings of participant responses.

Participants and Measures

The analyses for the present study included 158 male and 195 female young adults who completed the DIB-R at both time points. Most participants were Caucasian (83.9%) and single (99.4%). Some participants reported previous outpatient treatment for a psychological problem (24.1%), and a smaller percentage (2.0%) reported a history of at least one inpatient hospitalization. The majority of the sample met DSM-IV criteria for at least one lifetime Axis I disorder (61.5%), most commonly substance use disorder (40.5%), mood disorder (36.0%), and anxiety disorder (16.1%). Eating disorder (3.7%) was less prevalent.

At both time points, participants completed questionnaires and were administered semi-structured interviews, including the DIB-R, administered in random order across participants to control for order effects. Participants received either $10 per hour or research participation credit as compensation. Participants completed written consent forms prior to participating in the study. For more details regarding additional measures administered at the two waves of data collection, see Trull (2001) and Bagge, Nickell, Stepp, Durrett, Jackson, and Trull (2004).

The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines(DIB-R; Zanarini, et al., 1989). The DIB-R is a semi-structured interview designed to assess four areas related to BPD. The interview includes 97 items rated according to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors reported by the patient over a two-year period. These items determine the scores on 24 subsections, 22 of which are represented by “summary statements.” These 22 summary statements directly correspond to diagnostic criteria for BPD. The 24 subsections are then used in calculating scores on the 4 sections of affect, cognition, impulse action patterns, and interpersonal relationships. Thus, within the 4 sections, there are specific items and summary statements.

The Affect section includes 18 items that measure the summary statements for depression (e.g., felt helpless for days or weeks at a time), anger (e.g., quick-tempered), anxiety (e.g., felt very anxious a lot of the time), and other dysphoric affects (e.g., felt lonely a lot of the time). The Cognition section includes 27 items that comprise the summary statements for odd thinking/unusual perceptual abilities (e.g., been a very superstitious person), nondelusional paranoid experiences (e.g., often felt very distrustful or suspicious of other people), as well as psychotic experiences (e.g., heard voices or other sounds that no one else heard). The Impulse Action Patterns section includes items for summary statements measuring substance abuse (e.g., gotten high on prescription or street drugs), sexual deviance (e.g., impulsively gotten sexually involved with anyone or had any brief affairs), self-mutilation (e.g., deliberately hurt yourself without meaning to kill yourself), suicidal efforts (e.g., threatened to kill yourself), and other impulsive patterns (e.g., lost your temper and really shouted, yelled, or screamed at anyone). And lastly, the Interpersonal Relationships section includes items for summary statements corresponding to intolerance of aloneness (e.g., generally hated to spend time alone), abandonment/en-gulfment/annihilation concerns (e.g., repeatedly feared that you were going to be abandoned by those closest to you), counter-dependency (e.g., found yourself constantly offering to help friends, relatives, or coworkers), unstable close relationships (e.g.,… relationships been troubled by a lot of intense arguments), recurrent problems in close relationships (e.g., tended to feel very dependent on others), and troubled psychiatric relationships (e.g., did you get a lot worse as a result of this (any of these) thera-py(s)?). All items are rated on a scale from 2 to 0, where 2 (Yes), 1 (Probable), or 0 (No).

We examined several different methods of scoring the DIB-R (see Table 1). The first method involves scoring each section (affect, cognition, impulse action patterns, and interpersonal relationships) by adding the summary statements associated with the individual items within that section (e.g., unstable close relationships from the interpersonal relationships section). These scores are referred to as section scores. The second method produces what is referred to as a scaled section score, wherein a categorical score is assigned (0–2 or 0–3) based on the value of the section score along with additional qualifying information obtained during the interview (e.g., ruling out evidence of manic episodes). No internal consistency estimate is possible given that this is essentially a one-item score. Finally, a dimensional scoring procedure was used whereby scores on individual items within a section were added to create an item-based section score. The DIB-R includes 18 items for the affect section, 27 items for the Cognition section, 17 items for the Impulse Action Patterns section, and 32 items for the Interpersonal Relationships section. However, an examination of the distributions of individual items in the current sample indicated that some items in the Cognition, Impulse Action Patterns, and Interpersonal Relationships sections had no variance at either the first or second wave. Items in this category included the cognition items “believed that thoughts were being put into your mind by some external force,” “your feelings, thoughts, or actions were being controlled by another person or machine,” and “had any other beliefs that other people thought were definitely untrue, strange, or bizarre,” and the impulse action patterns item (at wave 1 only), “gone on any gambling sprees where you just kept placing bets even though you were consistently losing money?” Interpersonal Relationships items lacking variance included items referring to inpatient hospitalization (e.g., “developing a love affair with inpatient staff member,” “getting worse as a result of inpatient hospitalization,” “been the focus of conflicts on an inpatient unit,” “therapist asking you to leave treatment in the inpatient unit”).

TABLE 1.

Internal Consistency and Stability Estimates

| Variable |

Internal Consistency α Wave 1/Wave 2 |

Stability over time ICCs (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Section Scores | ||

| Affect | .82/.70 | .51(.43–.58) |

| Cognition | .51/.57 | .35(.25–.44) |

| Impulse Action Patterns | .54/.51 | .63(.56–.69) |

| Interpersonal Relationships | .74/.71 | .44(.35–.52) |

| Scaled Section Scores | ||

| Affect | — | .38(.29–.46) |

| Cognition | — | .29(.20–.38) |

| Impulse Action Patterns | — | .45(.38–.53) |

| Interpersonal Relationships | — | .27(.18–.35) |

| Item-Based Section Scores | ||

| Affect | .90/.85 | .56(.49–.63) |

| Cognition | .78/.76 | .44(.35–.52) |

| Impulse Action Patterns | .76/.71 | .66(.60–.71) |

| Interpersonal Relationships | .82/.79 | .56(.49–.63) |

Note. ICCs = intraclass correlation coefficients; CI = 95% confidence interval

The lack of variability on these items is understandable given the relatively low base rates of inpatient hospitalization and severe delusions in nonclinical samples. For the purpose of our analyses, we selected only those items that showed variability in the present sample. This left us with all original 18 items for the affect section, 24 of 27 items for the cognition section, 16 of 17 items for the impulse action patterns section, and 27 of 32 items for the interpersonal relationships section.

To test the path models below, we used the dimensional scoring procedure (i.e., item-based section scores). These estimates proved to be more internally consistent at both Wave 1 and at Wave 2 compared to the DIB-R section scores, and the item-based scores were also more stable over time (see Table 1). Furthermore, these scores provide more variability and therefore more information about severity of features compared to categorical approaches (e.g., scaled section scores) or indices that were created by adding a smaller number of categorical items (e.g., section scores). Using this scoring method, the interrater reliabilities, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), for the dimensional DIB-R item-based section scores at Wave 1 averaged .87 (range .67 to .97) and at Wave 2 averaged .96 (range .91 to .99).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the internal consistency estimates at each wave for the DIB-R section scores (sum of the summary statement scores for each section) as well as for the item-based section scores (sum of the items in each relevant section). As can be seen, the estimates for the item-based scores were higher in every case, which is typically the case with composites containing more items. Table 1 also presents stability estimates for the two year time period. Scaled section scores were the least stable, and item-based section score stabilities were somewhat higher than those derived from section scores. As noted above, it was on the basis of this reliability information that we made the decision to use item-based dimensional scoring for our path analyses.

Table 2 presents the correlations among item-based section scores. In order to test the three perspectives on the role of chronic negative affect and impulsivity in future BPD features, a series of path analyses were conducted using Mplus version 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007) with MLMV estimation, using listwise deletion. MLMV is a specialized maximum likelihood estimator that provides parameter estimates (e.g., standard errors and a mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square statistic) that are robust to nonnormality. Model fit was evaluated using the χ2 discrepancy index (nonsignificant values approaching zero indicate best fit), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values ≥ .95 indicate best fit), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; values ≥ .95 indicate best fit), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values ≤.05 indicate best fit).

TABLE 2.

Test-Retest and Intercorrelations for Item-Based Section Scores

| Subscale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affect (W1) | — | .52 | .42 | .75 | .60 | .34 | .31 | .54 |

| 2. Cognition (W1) | — | .35 | .56 | .34 | .44 | .32 | .41 | |

| 3. Impulse Action Patterns (W1) | — | .45 | .37 | .31 | .66 | .35 | ||

| 4. Interpersonal Relationships (W1) | — | .55 | .36 | .30 | .59 | |||

| 5. Affect (W2) | — | .50 | .40 | .75 | ||||

| 6. Cognition (W2) | — | .41 | .52 | |||||

| 7. Impulse Action Patterns (W2) | — | .46 | ||||||

| 8. Interpersonal Relationships (W2) | — |

Note. Values on the off-diagonal represent the correlations between subscales. W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2. Test-retest correlations are italicized in bold.

To test whether DIB-R Affect and Impulse Action Patterns item-based section scores were significant predictors of the other DIB-R scores at a second time point, each model of interest was tested against the baseline model, which included stability paths only. This allowed us to evaluate the extent to which Time 1 features predicted Time 2 features over and above the stabilities of each respective feature.

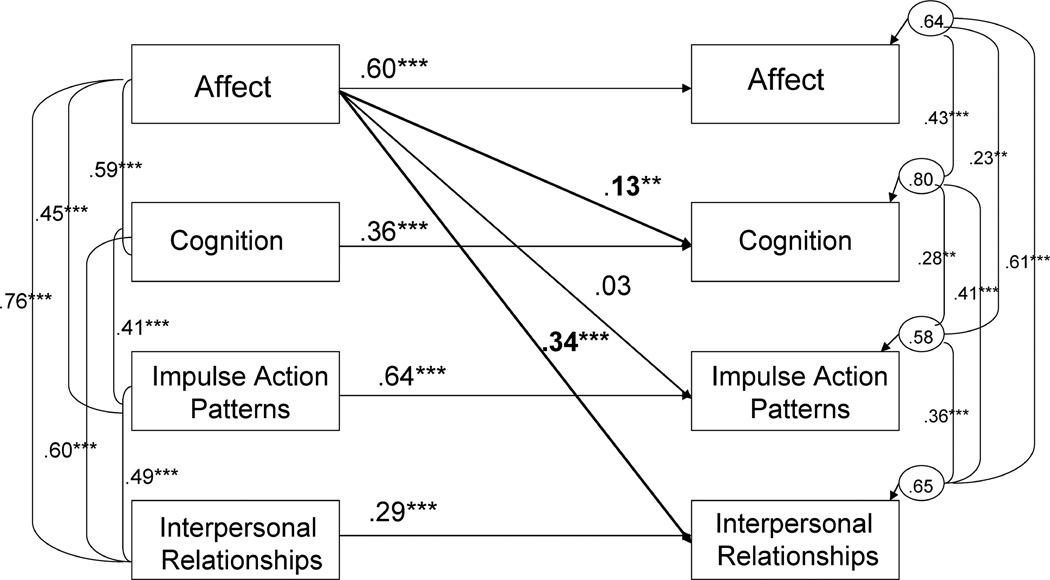

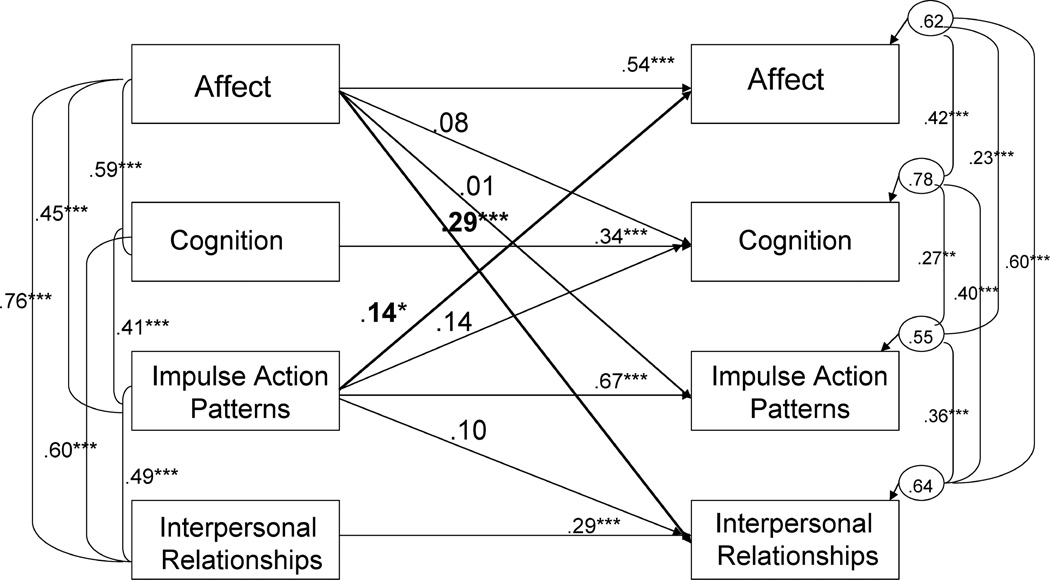

Table 3 presents the fit indices for each model. Results indicated that the NA model (Figure 1) showed the best fit to the data, χ2 (7, N = 353) = 14.589, p = .042, RMSEA = .055, CFI = .98, TLI = .96) and significantly improved model fit over a baseline model (consisting only of stability paths) using a χ2 difference test, Δ χ2 (3, N = 353) = 34.023, p < .001. The IMP model improved model fit over the baseline model, Δ χ2 (3, N = 353) = 10.596, p = .014, but showed decreased goodness-of-fit, χ2 (8, N = 353) = 31.239, p = .0001, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .93, TLI = .88, compared to the NA model. Finally, the NA-IMP model (Figure 2), although providing a good fit to the data, did not significantly improve model fit over the NA model, Δ χ2 (3, N = 353) = 5.50, p = .14.1

TABLE 3.

Model Fit Indices

| Model | χ2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δ χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 33.204*** | .93 | .89 | 0.09 | |

| NA | 14.589* | .98 | .96 | 0.06 | 34.023*** |

| IMP | 31.239** | .93 | .88 | 0.09 | 10.596* |

| NA-IMP | 11.540* | .98 | .95 | 0.06 | 26.131*** |

Note χ2 = χ2discrepancy index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation; Δχ2 = change in χ2fit over baseline model.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

FIGURE 1.

Negative Affect (NA) model.

FIGURE 2.

Combination Negative Affect-Impulsivity (NA-IMP) model.

DISCUSSION

As expected, we found that the dimensional (item-based) scoring produced the most reliable estimates. Although many of the scaled section scores and summary-based section scores demonstrated acceptable reliability, some scores were below an acceptable range (e.g., Cognition scaled section score). These findings suggest that future research using the DIB-R may benefit from an item-based scoring procedure, rather than a categorical (scaled section scores) or summary-statement based scoring procedure. Using item-based scoring, the DIB-R demonstrated strong internal consistency, good test-retest, and excellent inter-rater reliability.

Second, we found that DIB-R Affect scores were the strongest and most consistent predictors of future borderline personality features, controlling for the stability of these features from initial assessment. These results suggest that chronic dysphoria or negative affect is most responsible for changes in borderline features over time, except for changes in impulsivity. Furthermore, neither the IMP model nor the combined NA-IMP model showed significantly improved fit over the NA model. Even though the IMP model demonstrated significant paths from Wave 1 Impulse Action Patterns to Wave 2 BPD features, this model was a poorer fit to the data compared to the NA model. Furthermore, modification indices did not indicate that additional paths from Impulse Action Patterns would significantly improve the fit of the NA model.

These results partially support Tragesser et al.’s (2007) finding that affective instability best predicted future BPD symptoms. The current study found that the negative affectivity model provided the best fit to the data. However, unlike the findings in Tragesser et al. (2007), changes in impulsivity were not accounted for by negative affectivity. Across all models, the only significant predictor of Impulse Action Patterns scores at Wave 2 were these same scores at Wave 1. This suggests that although negative affectivity may account for other BPD features, impulsivity may be a partially distinct construct that is less influenced by chronic negative affect and other BPD features. In light of previous findings, it appears that affective instability may be a better predictor of future impulsivity in BPD. As mentioned above, the DIB-R Affect section items do not assess instability in these affects but rather the chronicity of the extreme levels of the negative affects.

Despite this difference in the results, the overall consistency in findings between Tragesser et al. (2007) and the current study is noteworthy given the differences in the measures used across analyses. Although Tragesser and colleagues (2007) relied on a brief 24-item questionnaire measure, the present study utilized a longer semi-structured interview. Furthermore, the DIB-R includes a measure of cognitive disturbances, a feature of BPD that was not assessed previously in Tragesser et al.’s (2007) study. Therefore, the present study builds on this previous research by testing the extent to which chronic negative affectivity accounts for cognitive disturbance, and by showing that levels of chronic negative affectivity predict changes in cognitive disturbances over time. The results of the present study also suggest that changes in impulsivity over time cannot be explained by chronic negative affectivity alone.

Overall, these results are most consistent with Linehan’s (1993) perspective, which suggests that affective instability or emotional dysregulation is a core feature influencing many of the other BPD symptoms. According to this perspective, those with BPD are emotionally vulnerable. Specifically, these individuals have an acute sensitivity to stimuli that elicit negative emotions, tend to experience negative emotions quite intensely, and typically show a slow return to baseline following emotional arousal. The experience of negative affect itself can lead to a variety of other problems and these problems are likely exacerbated by severe emotion dysregulation characteristic of BPD. For example, individuals who suffer from chronic affective instability are more likely to have interpersonal problems characterized by relationship conflicts, angry outbursts at others, and changing views on relationships. Finally, strong and at times unpredictable negative affect states may lead to a disjointed sense of experience which in turn impacts one’s overall sense of consistency of the world and of the self, as well as transient, stress-related psychotic experiences related to BPD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Our results have a number of implications. First, because our findings support theoretical accounts that emphasize the central role of emotion dysregulation (Linehan, 1993), they indicate the importance of understanding the links between affective instability, chronic negative affect, and other core features of the BPD. Second, there is support for the perspective that impulsivity is a unique component that contributes to the overall presentation of BPD (Siever & Davis, 1991; New & Siever, 2002). Specifically, the finding that impulsive action patterns scores were not predicted by negative affectivity in the present study indicates that impulsivity (as conceptualized by the DIB-R) is relatively independent and not simply a manifestation of chronic negative affectivity. This result is consistent with perspectives emphasizing the combination of affective instability with impulsivity to produce the entire constellation of BPD symptoms. However, given that the DIB-R does not assess affective instability specifically, conclusions about the relationship between AI and impulsivity can not be drawn from these results.

It is important to acknowledge other limitations in the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. Although strengths of the present design are that it is prospective and controls for stability effects of BPD features, future research might test these models over longer periods of time and with different age groups and populations. Longer time frames may reveal different patterns of relationships between initial levels and subsequent borderline features. For instance, although negative affectivity in early adulthood may be the best predictor of subsequent DIB-R borderline features, it is possible that this may not be the case in later adulthood. In addition, the present study involved young adults who initially enrolled in college—many of whom endorsed significant borderline features but did not necessarily meet criteria for a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of BPD. Although there is no reason to believe that the relationship among borderline features would be different in a clinical sample of this age group, tests of these relations in a clinical sample would assess the generalizability of these results and the validity of the findings for more severe forms of BPD.

In summary, the results of our prospective study are most consistent with the perspective that affective instability/negative affectivity is a core BPD feature that influences other symptoms, although impulsivity may also be a distinct feature when considering impulse control problems in BPD. These results highlight the importance of both assessing levels of baseline negative affectivity and affective instability in individuals with significant BPD features. Emotion dysregulation should be targeted in treatment interventions, while recognizing the role that impulsivity plays in certain aspects of the disorder.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant MH52695 awarded to Timothy J. Trull, and NIH grant T32 AA13526.

Footnotes

Chi-Square difference tests using MLMV estimation require special calculations and, thus, the degrees of freedom and values for the difference tests are not derived from the values presented in Table 1. See Muthe´n & Muthe´n (1998–2007) for details.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed., Text Revision) Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bagge C, Nickell A, Stepp S, Durrett C, Jackson K, Trull T. Borderline personality disorder features predict negative outcomes 2 years later. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:279–288. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Fishman S, Strong DR, Kruglanski AW, Lejuez CW. Borderline personality disorder in the context of self-regulation: Understanding symptoms and hallmark features as deficits in locomotion and assessment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:198–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CZ, Bradley R, Westen D. Affect regulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:69–77. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198138.41709.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Lezenweger MF. A neurobehavioral dimensional model. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 136–176. [Google Scholar]

- Distel MA, Hottenga JJ, Trull TJ, Boomsma DI. Chromosome 9: Linkage for borderline personality disorder features. Psychiatric Genetics. 2008;18:302–307. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283118468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropou-lou V, New AS, Goodman M, Silverman J, et al. Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:358–370. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.4.358.19181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullgren G. Factors associated with completed suicide in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1988;176:40–44. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz JE, Morey LC. Use of structured self-report assessment to diagnose borderline personality disorder during major depressive episodes. Assessment. 2001;8:291–300. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan NM, Heard HL. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. In: Clarkin JF, Marziali E, Munroe-Blum H, editors. Borderline personality disorder: Clinical and empirical perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. pp. 248–267. [Google Scholar]

- Links PS, Heslegrave R, van Reekum R. Impulsivity: Core aspect of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1999;13:1–9. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1999.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Links PS, Mitton MJ, Steiner M. Stability of borderline personality disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;38:255–259. doi: 10.1177/070674379303800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Links PS, Steiner M, Huxley G. The occurrence of borderline personality disorder in the families of borderline patients. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1988;2:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ralevski E, Morey LC, Gund-erson JG, et al. Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: Toward a hybrid model of Axis II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:883–889. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Montgomery D, Baldwin D, Green M. Intermittent 3-day depressions and suicidal behaviour. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;145:573–577. doi: 10.1159/000118606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality assessment inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Fifth edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998– 2007. [Google Scholar]

- New AS, Siever LJ. Neurobiology and genetics of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Silk KR, Stavro G, Miller T. Disinhibition and borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:1129–1149. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. The biology of impulsivity and suicide. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;23:11–25. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedler J, Westen D. Dimensions of personality pathology: An alternative to the five-factor model. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1743–1754. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psycho-biologic perspective on the personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1647–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JM, Pinkham L, Horvath TB, Coccaro EF, Klar H, Schear S, et al. Affective and impulsive personality disorder traits in the relatives of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1378–1385. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA. The borderline diagnosis II: Biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:951–963. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Meltzer CC, Becker C, Greer PJ, Kelly TM, Constantine D. Impulsivity and prefrontal hypometabolism in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2003;123:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Solhan M, Schwartz-Mette R, Trull TJ. The role of affective instability and impulsivity in predicting future BPD features. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:603–614. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults 1. Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Structural relations between borderline personality disorder features and putative etiological correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:471–481. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett C. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Useda JD, Conforti K, Doan BT. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: 2. Two-year outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:307–314. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Lynam DR, Costa PT. Borderline personality disorder from the perspective of general personality functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:193–202. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Reekum R, Links PS, Mitton MJ, Fedorov C, Patrick J. Im-pulsivity, defensive functioning, and borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:81–84. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath M, Alnaes R, Torgersen S. Coping in DSM-IV options personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10:335–344. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1998.12.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Zlotnick C, Costello E. Affect regulation in women with borderline personality disorder traits. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:693–696. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, et al. Borderline personality disorder criteria associated with pro-spectively observed suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1296–1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC. BPD as an impulse spectrum disorder. In: Paris J, editor. Borderline personality disorder: Etiology and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vuja-novic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the revised diagnostic interview for borderlines. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Franken-burg FR, Chauncey DL. The revised diagnostic interview for borderlines: Discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]