Abstract

Background

The indications and contra-indications for intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) use in ischemic stroke can be confusing to the practicing neurologist. Here we seek to describe practice patterns regarding decision-making among US stroke clinicians.

Methods

Stroke clinicians (attending and fellow) from the eight NIH SPOTRIAS (Specialized Programs of Translational Research in Acute Stroke) centers were asked to complete a survey ahead of the 2012 SPOTRIAS Investigators’ meeting.

Results

A total of 51 surveys were collected (71% response rate). The majority of responders were attending physicians (68%). Only 18% of clinicians reported strictly adhering to current AHA guidelines for treatment within 3 hours from symptom onset; this increased to 51% for the ECASS III criteria in the 3 to 4.5 hour time frame. All clinicians treat eligible patients in the 3 to 4.5 hours time frame. The great majority will recommend rtPA in the following scenarios: elderly individuals irrespective of age (97%), severe stroke irrespective of NIHSS (95%), or suspected stroke with seizures at symptom onset (91%). None recommended rtPA in the setting of an INR > 1.7. Most clinicians defined mild strokes as an exclusion based on the perceived disability of the deficit (80%) rather than on a specific NIHSS threshold.

Conclusions

Most surveyed stroke clinicians seem to find that the current IV rtPA eligibility criteria for the 3-hour time frame too restrictive. All would recommend rtPA to eligible patients in the 3 to 4.5 hour time frame despite the absence of an FDA-approved indication.

Keywords: all Cerebrovascular disease/Stroke, infarction, Other Cerebrovascular disease/Stroke, thrombolysis, stroke treatment, tissue plasminogen activator, rtPA

Introduction

Fibrinolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is the pillar of current acute stroke therapy.[1-4] Despite its increased use in the US, rtPA is still administered to only about 5% of patients with an acute ischemic stroke.[5] This is largely due its strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.[6] These criteria are primarily taken from the pivotal NINDS study that led to FDA approval and expert opinion.[7] The NINDS study results have been replicated in real-life scenarios in multiple centers worldwide when these criteria are followed.[8, 9]

Over the last decade, various publications have provided nonrandomized data on the outcome of patients treated with rtPA outside the established guidelines.[10-13] These reports, in addition to imaging advances and greater experience with IV rtPA, have led many to challenge the necessity of some of the current exclusion criteria.[7, 14, 15] However, there is also evidence that straying too far from established treatment protocols can lead to increased rates of complications.[16, 17] Furthermore, the definitions of specific criteria have not been well-delineated and discrepancies exist between the rtPA product label and current treatment guidelines (Table 1). In this context, we sought to describe practice patterns regarding IV rtPA decision-making among stroke clinicians from high-volume academic centers.

Table 1.

Contraindications and Warnings to IV rtPA use.

| Clinical variable | Activase Insert | 2007 AHA / ASA Guidelines | 2013 AHA / ASA Guidelines | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from symptom onset > 3 hours | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Time from symptom onset > 4.5 hours | ✓ | |||

| 3 to 4.5 hours from symptom onset: | ✓ | The benefit of IV rTPA in the presence of one or more of these criteria is not well established | ||

| Age > 80 years (a) | ✓ | |||

| Any oral anticoagulant use (a) | ✓ | |||

| NIHSS > 25 (a) | ✓ | |||

| History of stroke and diabetes (a) | ✓ | |||

| Imaging evidence of ischemic injury > 1/3 of MCA territory | ✓ | |||

| Presence of intracranial hemorrhage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Suspicion of subarachnoid hemorrhage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Serious head trauma / stroke < 3 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Guidelines obviate the word “serious” |

| Recent intracranial, intraspinal surgery | ✓ | ✓ | Less than 3 months in the insert. | |

| Myocardial infarction < 3 months | ✓ | RC | ||

| Recent GI or urinary tract hemorrhage | W | ✓ | RC | Guidelines suggest < 21 days |

| Recent major surgery | W | ✓ | RC | Guidelines suggest < 14 days |

| Recent arterial puncture at a non-compressible site | W | ✓ | ✓ | Guidelines suggest < 7 days |

| History of intracranial hemorrhage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Uncontrolled hypertension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | >185 mm Hg systolic or > 110 mm Hg diastolic |

| Seizure at the onset of symptoms | ✓ | RC | RC | |

| Active internal bleeding | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Intracranial neoplasm or AVM | ✓ | ✓ | Known presence of neoplasm or AVM. Brain imaging with contrast or angiography are not required prior to IV rTPA | |

| Intracranial aneurysm | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Current use of oral anticoagulants irrespective of INR | ✓ | Guidelines allow IV rTPA while on warfarin therapy if INR is <1.7. | ||

| INR > 1.7 or PT > 15 seconds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Heparin < 48 hours and prolonged aPTT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Platelet count < 100'000/mm3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Use of novel oral anticoagulants and abnormal coagulation tests | N/A | N/A | ✓ | Coagulation tests include aPTT, INR, platelet count, and ECT; TT; or factor Xa activity assay |

| Conditions where bleeding constitutes a significant hazard or would be particularly difficult to manage due to its location (b) | W | |||

| Acute trauma (fracture) | W | ✓ | RC | |

| Minor and isolated neurological deficits or spontaneously clearing symptoms | W | ✓ | RC | |

| Major deficits or NIHSS > 22 | W | W | ||

| Major early infarct signs on CT scan | W | ✓ | ✓ | Guidelines suggest a CT scan with hypodensity > 1/3 of cerebral hemisphere |

| Glucose < 50 mg/dl or > 400 mg/dl | W | ✓ | ✓ | Guidelines do not mention a higher glucose value |

| Pregnancy | W | RC | ||

| Advanced age (e.g., over 75 years) | W | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | W | Not a warning in clinical practice | ||

| High likelihood of left atrial heart thrombus (e.g. mitral stenosis with atrial fibrillation) | W | Variable is likely very rare and was not included in survey. | ||

| Septic thrombophlebitis or occluded AV cannula at seriously infected site | W | Variable is likely very rare and was not included in survey. | ||

Criterion present in the 2009 AHA Science Advisory

This includes acute pericarditis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, hemostatic defects, significant hepatic dysfunction, diabetic hemorrhagic retinopathy, and other hemorrhagic ophthalmic conditions.

W = Warning, RC = Relative contraindication, INR = International Normalized Ratio, PT = Prothrombin Time, aPTT = Activated partial thromboplastin time, CT = computerized cranial tomography, AHA = American Heart Association, ASA = American Stroke Association, NSTEMI = Non ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI = ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, AVM = Arterio-venous malformation, GI = Gastrointestinal, ECT = Ecarin clotting time, TT = Thrombin time.

Methods

We invited all stroke attendings and fellows (stroke clinicians) from SPOTRIAS (Specialized Programs of Translational Research in Acute Stroke) centers to participate in a survey regarding their acute stroke practice patterns. SPOTRIAS is a national network of eight specialized stroke treatment and research centers funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with a goal of reducing disability and mortality through collaborative laboratory and clinical investigation (www.spotrias.org). At the time of the survey, there were eight SPOTRIAS sites: University of California Los Angeles, University of California San Diego, University of Texas Houston, Washington University in St. Louis, Columbia University, Partners (Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital), NINDS Intramural Program, and the University of Cincinnati.

Stroke clinicians who had made the decision to prescribe or recommend fibrinolytic therapy to at least one patient with a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke within the previous 12 months were asked to complete the survey; residents were excluded. The survey consisted of questions about their treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke (Appendix e-1).

A pilot survey modeled on the 2007 AHA guidelines,[18] 2009 AHA science advisory on the expansion of treatment time windows,[19] and the rtPA product label was administered to stroke clinicians at the University of Cincinnati on March 26, 2012. Feedback from this pilot survey was used to modify and expand the questions, creating the study survey (Appendix e-1). The study survey was then distributed to the Principal Investigators of each SPOTRIAS center to share among their faculty and fellows by email and an additional opportunity was given at the 2012 SPOTRIAS investigators’ meeting. Data collection took place during the months of April and May 2012. The surveys were designed, stored, and analyzed online using SurveyMonkey® software. All questions required a single answer unless stated otherwise. Because of wording differences between the pilot and final surveys, data from the pilot survey were not included for this analysis. In order to include data from the University of Cincinnati, a second survey including questions present only in the final survey but not in the pilot survey was distributed. The replies from this second survey are also included in this analysis and were used to calculate our response rate. Additionally, questions 5 and 6 (Appendix e-1) were excluded from this manuscript due to concerns by those interviewed regarding the ambiguity of the wording and difficulty in interpretation of results. All data collection was finalized on May 17, 2012. We report only the data regarding intravenous fibrinolysis. This study was given exempt status by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board.

Results

We estimated that our survey population of interest consisted of 70 stroke clinicians (attending physicians members of each institution's stroke team and vascular neurology fellows) within the SPOTRIAS network. We collected 51 surveys (71% response rate), including four physicians who did not treat an acute stroke patient in the previous 12 months and whose responses were excluded. A total of 47 responses remained available for analysis.

The majority (2/3) of responders were attending physicians at academic institutions (66%; n=31). Approximately 1/3 of respondents were stroke fellows (32%; n=15). The remaining physician worked primarily in the community (2%).

Specific survey results are described below

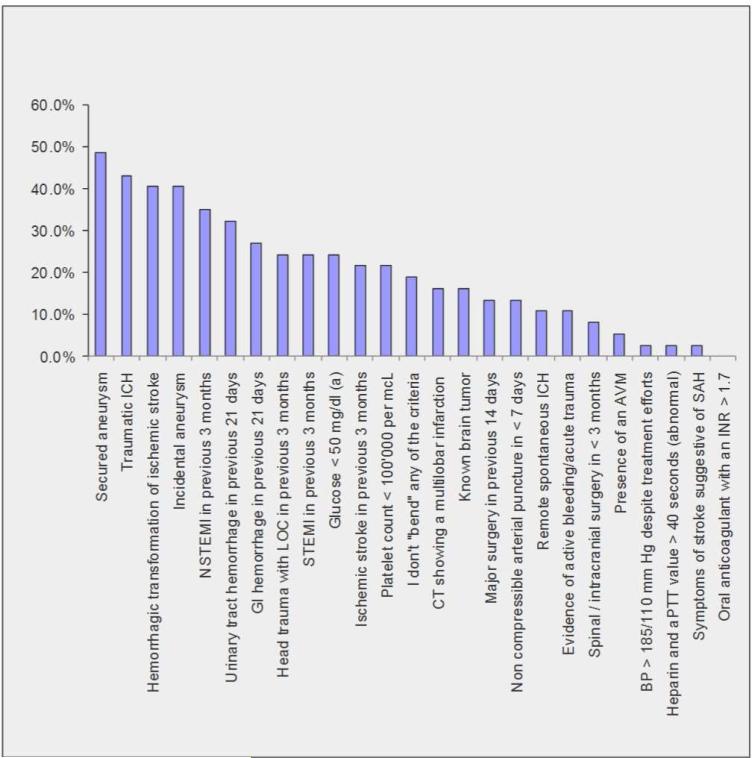

A) Question: “Which potential rtPA exclusion criteria do you “bend” for patients with a perceived disabling stroke? Multiple answers allowed.”

Only 18% (n=7) of responders would adhere strictly to all AHA guidelines and insert criteria. The most frequently waived criterion (49%, n=18) was having a previously secured intracranial aneurysm. Responses for each individual criterion are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Frequency of AHA guideline and rtPA insert exclusions that are broken for disabling stroke patients.

Abbreviations: ICH = Intracranial hemorrhage; NSTEMI = Non ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI = ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; GI = Gastrointestinal; LOC = loss of consciousness; AVM = arteriovenous malformation; aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; SAH = Subarachnoid hemorrhage. (a) = Deficits persist after glucose correction. (Figure attached as JPEG file)

B) Question: “What additional ECASS III rtPA contraindication criteria do you “bend” for patients with a disabling stroke in the 3 – 4.5 hour treatment window?” Multiple answers allowed.”

Half the experts surveyed (51%; n=19) would not violate any of the ECASS III criteria (i.e., age greater than 80, history of diabetes and prior stroke, any oral anticoagulant use, or NIH stroke scale [NIHSS] greater than 25). About 30% of respondents would break each individual ECASS III criteria except for an abnormal PTT, in which case 5% (n=2) would recommend rtPA. Similarly, 5% replied they would break all of the ECASS III criteria. Four physicians skipped this question.

C) Question: “At this time, do you treat patients that present in any of the following time windows from symptom onset with IV rtPA? Multiple answers allowed.”

All the responders treat patients 4.5 hours from symptom onset; 44% (n=16) treat patients who wake up with stroke deficits, of which 56% (n=9) commented they did so only within a study protocol; 22% (n=8) will treat patients in the 4.5 – 6 hour time frame; and 8% (n=3) will treat patients more than 6 hours from symptom onset but not those who wake up with a stroke.

D) Question: “If you suspect a patient is experiencing significant deficits attributable to an acute ischemic stroke but they present with a seizure at symptom onset, do you recommend fibrinolytic therapy? (Provided other inclusion / exclusion criteria are met)?”

The great majority (91%; n=42) will recommend rtPA in this scenario.

E) Question: “In patients receiving warfarin, up to what INR do you feel comfortable administering IV rtPA?”

The majority of clinicians (84%; n=39) feel comfortable recommending IV rtPA up to an INR of 1.7, 4% (n=2) choose an INR of 1.6, and 2% (n=1) choose an INR of 1.5 and 1.4. None chose an INR greater than 1.7.

F) Question: “Is there an NIHSS below which you usually do not offer IV rtPA (or does this depend on the perceived disability of the deficit)?”

The majority of experts (80%; n=29) do not have a NIHSS threshold below which they would not recommend rtPA; they make this decision based on the perceived disability of the deficit. Few use a specific NIHSS thresholds of 0 (8%; n=3) and 2 (2%; n=1). Three (8%) marked “other” and listed NIHSS, perceived disability, and/or presence of arterial occlusion as considerations.

G) Question: “Is there an NIHSS above which you do not offer IV rtPA?”

The great majority of experts (96%; n=44) do not restrict rtPA treatment based on an upper NIHSS; 2% (n=1) selected an NIHSS greater than 30, and 2% (n=1) selected an NIHSS greater than 40.

H) Question: “Is there an upper age limit beyond which you do not offer IV rtPA in the < 3 hour time window?”

The great majority of experts (97%; n=35) do not determine patients ineligible for rtPA based on age; 3% (n=1) selected an upper age limit of 80.

I) Question: “Do you currently use perfusion imaging to guide your therapy decisions for acute ischemic stroke patients?”

About half (54%; n=25) of stroke experts surveyed do not use perfusion imaging to make acute treatment decisions, 26% (n=12) routinely use it, and 20% (n=9) rarely use it.

J) Question: “What type of perfusion imaging do you use?

Over half (57%; n=12) of those who use perfusion imaging utilize both CT and MR techniques depending on availability; 28% (n=6) utilize CT only, and 14% (n=3) utilize MR perfusion only.

Discussion

Based on treatment practices, the majority of the surveyed stroke clinicians seem to believe that current practice guidelines regarding the use of IV rtPA for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke are too restrictive. Only 14% of respondents noted that they do not violate any of the AHA guideline, rtPA package insert, or ECASS III exclusion criteria for fibrinolysis (Table 1). Besides seizures at stroke onset, there was little agreement on which exclusion criteria should be modified, with no other criterion being agreed upon by more than half of the clinicians. It is also apparent that some criteria are currently too broad and need more specific definitions. For example, fewer experts would treat a patient with a prior history of an aneurysm if it was incidental (vs. secured), or if there was a recent STEMI (vs. NSTEMI), or previous spontaneous ICH (vs. traumatic).

The exclusion criterion of seizures at stroke onset is likely outdated at this point. The main concern is exposing a patient with a stroke mimic to the unwanted effects of systemic fibrinolysis. Additionally, clinical trials often exclude these subjects as they might confound analyses of baseline deficits that are partly attributable to the postictal state. However, case series data suggest that the risk of rtPA in this scenario is very low (<0.5%).[20, 21] Additionally, the 2007 AHA guidelines[18] (and now the 2013 AHA guidelines)[6] recommend that patients with a seizure at symptom onset may be eligible for treatment as long as the treating physician is convinced the symptoms are secondary to stroke. It is therefore not surprising that 90% of stroke experts recommended treatment in this scenario.

The exclusion criterion most frequently waived by surveyed stroke clinicians (49%) was presence of a previously secured intracranial aneurysm. This is an infrequent reason for IV rtPA exclusion (< 1% of eligible cases).[22] Case series of patients with incidental aneurysms and ischemic strokes report few bleeding complications when treated with IV rtPA. [23-25] To our knowledge, there is no publication analyzing comparative bleeding risks based on aneurysm characteristics such as size, location, morphology, and symptomatology or treatment (i.e., incidental, recurrent, or secured).

Several of the rtPA eligibility criteria need further study. For example, many experts are willing to give rtPA to those with a recent NSTEMI; this is likely because the feared complication of hemopericardium is more likely to occur only after STEMI, or more specifically, transmural infarcts.[26] Systematic data of MI patients treated with IV rtPA are lacking, but all published case reports of hemopericardium are in the setting of STEMIs.[27] A recent review concluded that the time window from MI to fibrinolysis could be shortened from 3 months to 7 weeks based on pathological data suggesting that myocardial repair is complete at this time.[26] Other rtPA criteria requiring further study and reconsideration include remote traumatic ICH or urinary tract hemorrhage.[13, 14] In the 2013 AHA guidelines, recent acute myocardial infarction and recent gastrointestinal or urinary tract hemorrhage have been changed to relative (as opposed to absolute) exclusion criteria.[6]

The precise thresholds at which bleeding complications outweigh the benefits of fibrinolysis for patients on anticoagulation therapies are unknown. For patients on warfarin therapy, national guidelines allow fibrinolysis up to an INR of 1.7.[6] However, the rtPA product label lists any oral anticoagulation, irrespective of INR, as a treatment contraindication. Initially, small case series reported mixed findings regarding the safety of fibrinolysis in sub-therapeutic warfarin therapy.[12, 28] However, two recent, larger studies, have provided compelling data to suggest safety in the setting of an INR<1.7; no increased risk of ICH was reported in patients taking warfarin with an INR up to 1.7 who were administered IV rtPA in retrospective analyses of the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Registry [29] (n=1802) and the Canadian Stroke Network[30] (n=125). Data on the safety of fibrinolysis in patients with an INR greater than 1.7 are lacking.[29] Consistent with available data, no one was willing to treat patients with an INR greater than 1.7. The safety of IV rtPA in the setting of the novel oral anticoagulants is not known. The 2013 guidelines recommend that those on direct thrombin inhibitors might be treated with IV rtPA if coagulation tests such as aPTT, INR, platelet count and either ecarin clotting time, thrombin time, or an appropriate factor Xa activity assay are within normal limits, or at least 48 hours from the last ingested dose have elapsed (if renal function is normal).[6] Both thrombin time and ecarin clotting time are more sensitive than aPTT to the presence of dabigatran, although they could unnecessarily exclude patients who could be safely treated.

In 2008, the ECASS III study showed benefit of fibrinolysis when given 3 to 4.5 hours from symptom onset.[2] This finding was upheld in a pooled analysis of the major randomized controlled trials of rtPA.[31] In 2009 the AHA / ASA published recommendations expanding the time window for treatment up to 4.5 hours from symptom onset (class I recommendation, level of evidence B)[19] with the same exclusions used in the ECASS III study; age > 80, any oral anticoagulant use, NIHSS > 25, or history of both stroke and diabetes. This recommendation was modified in the 2013 guidelines to also exclude those with imaging evidence of ischemic injury involving more than one third of the MCA territory.[6] However, this extended time window (3-4.5 hour) indication has not been added to the FDA label of rtPA to date. In our survey, 100% of experts would treat eligible patients in the 3 to 4.5 hour from symptom onset time frame and one out of five would treat beyond 4.5 hours, although some noted that the latter would only be done in the setting of clinical trials. Half would violate the specific eligibility criteria from the ECASS III trial. This approach is supported by a pooled analysis of major IV rtPA trials[32] and retrospective single center data[10, 11, 13]; interestingly, these data do not demonstrate an increased sICH risk in the setting of fibrinolysis from 3 to 4.5 hours using the broader criteria from the <3 hour time window. From our data, however, we are unable to determine the specific rationales for not using ECASS III eligibility criteria.

In the < 3 hour time window, nearly all surveyed (with the exception of one clinician) would not exclude a patient based on age or stroke severity. This approach is supported by both observational cohorts and the recently completed randomized IST-3 study.[3], [4, 12, 15]

CT and MR perfusion imaging based assessment of ischemic penumbra, or tissue that is ischemic but not irreversibly injured, is a promising approach to select patients who may benefit from fibrinolysis at extended timeframes or in ambiguous clinical situations.[33] For example, perfusion imaging may be used to aid in the diagnoses of acute cerebral ischemia when alternative diagnosis are possible (such as subtle sub-arachnoid hemorrhage) or to determine tissue at risk in wake up strokes. However both are in need of standardization[34] and confirmatory studies before widespread clinical use can be recommended.[35] Nevertheless, these techniques were being used to select patients for fibrinolysis at some stroke centers on our survey. In our study, half of those surveyed currently use perfusion imaging to guide treatment decisions without a clear preference for one imaging technique over the other. However, our survey was performed prior to the release of the recently published MR Rescue trial that failed to prove that patients selected for revascularization based on penumbral imaging patterns have an improved outcome compared to those treated medically or without such patterns.[36]

Finally, minor stroke is a common contraindication to fibrinolysis. Minor or improving stroke symptoms are the most common contraindication for fibrinolysis, accounting from up to one-half[37] of those not treated but otherwise eligible. Its definition has been unclear in guidelines to date. In our survey, the majority (80%) of experts did not define mild stroke based on the NIHSS, but rather on the perceived disability of the deficit.

A strength of our study is the inclusion of stroke physicians only, who belong to high volume stroke centers and are in geographically diverse areas of the United States. However, our study also has several limitations. We designed the survey prior to the publication of the 2013 AHA guidelines on acute stroke management,[6] however the recommendations regarding IV rtPA use did not change significantly from the previous guideline[18] and interim science advisory[19] (Table 1). We think this would have made little impact on our results. Although we specifically requested survey participants to reply according to their routine clinical practice, some may have included their practice in ongoing clinical trials. Those surveyed from the SPOTRIAS stroke network may not be representative of all the stroke experts in the US. Furthermore, we did not collect the institutional affiliation of each survey responder, and cannot exclude overrepresentation of particular SPOTRIAS sites. Finally, two questions were reported to be ambiguous and had to be excluded. However, our study is not intended to offer practice guidelines or expert consensus, but rather to describe practice patterns and offer a review of the literature.

In conclusion, based on practice patterns, most stroke clinicians within the SPOTRIAS network seem to find that current treatment guidelines for fibrinolysis in the 3-hour timeframe from symptom onset are too restrictive. Additionally, the absence of an FDA indication in this time window does not seem to deter treatment within the expanded 3-4.5 hour window; however, there was less consensus about whether to expand ECASS III trial-defined eligibility criteria in this window to match the <3 hour window. Further study of the safety of expanding the IV rtPA eligibility criteria seems warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Study Funding: Supported by NIH, NINDS (P50 NS044283-09)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statistical analysis: De Los Rios F, MD. University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio

Authors and individual contributions to the manuscript:

Dr. De Los Rios: Principal Investigator. Drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept and design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision or coordination.

Dr. Kleindorfer: Drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept and design, analysis or interpretation of data, study supervision or coordination, obtaining funding.

Dr. Guzik, Dr. Sangha, Dr. Kumar, Dr. Ortega-Gutierrez, Dr. Grotta, Dr. Lee, Dr. Meyer, and Dr. Schwamm: Drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data.

Dr. Khatri: Drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, study concept and design, analysis or interpretation of data, study supervision or coordination.

References

- 1.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;333:1581. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. NEnglJMed. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.group ISTc. Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, et al. The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:2352–2363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60768-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischaemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2364–2372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, et al. Recombinant Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Use for Ischemic Stroke in the United States A Doubling of Treatment Rates Over the Course of 5 Years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong D. Are all IV thrombolysis exclusion criteria necessary? Being SMART about evidence-based medicine. Neurology. 2011;76:1780–1781. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiegand N, Luthya R, Vogel B, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis for ischaemic stroke is also safe and efficient without a specialised neuro-intensive care unit. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2004;134:14–17. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suissa L, Bozzolo E, Lachaud S, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with rt-PA in stroke: Experience of the Nice stroke unit. RevNeurol. 2009;165:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronin CA, Shah N, Morovati T, et al. No Increased Risk of Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage After Thrombolysis in Patients With European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) Exclusion Criteria. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:1684–1686. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.656587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubiera M, Ribo M, Santamarina E, et al. Is it Time to Reassess the SITS-MOST Criteria for Thrombolysis? A Comparison of Patients With and Without SITS-MOST Exclusion Criteria. Stroke. 2009;40:2568–2571. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillan M, Alonso-Canovas A, Garcia-Caldentey J, et al. Off-label intravenous thrombolysis in acute stroke. European Journal of Neurology. 2012;19:390–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meretoja A, Putaala J, Tatlisumak T, et al. Off-Label Thrombolysis Is Not Associated With Poor Outcome in Patients With Stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:1450–1458. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aleu A, Mellado P, Lichy C, et al. Hemorrhagic complications after off-label thrombolysis for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:417–422. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254504.71955.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Keyser J, Gdovinova Z, Uyttenboogaart M, et al. Intravenous alteplase for stroke - Beyond the guidelines and in particular clinical situations. Stroke. 2007;38:2612–2618. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzan IL, Hammer MD, Furlan AJ, et al. Cleveland Clinic Health System Stroke Quality Improvement T. Quality improvement and tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: a Cleveland update. Stroke. 2003;34:799–800. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000056944.42686.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzan IL, Furlan AJ, Lloyd LE, et al. Use of tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: the Cleveland area experience. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1151–1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams HP, Jr., del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38:1655–1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, et al. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: A science advisory from the American heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernyshev OY, Martin-Schild S, Albright KC, et al. Safety of tPA in stroke mimics and neuroimaging-negative cerebral ischemia. Neurology. 2010;74:1340–1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dad5a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guillan M, Alonso-Canovas A, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, et al. Stroke mimics treated with thrombolysis: Further evidence on safety and distinctive clinical features. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2012;34:115–120. doi: 10.1159/000339676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Los Rios la Rosa F, Khoury J, Kissela BM, et al. Eligibility for Intravenous Recombinant Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Within a Population: The Effect of the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III Trial. Stroke. 2012;43:1591–1595. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.645986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards NJ, Kamel H, Josephson SA. The Safety of Intravenous Thrombolysis for Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Pre-Existing Cerebral Aneurysms A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Stroke. 2012;43:412–416. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.634147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheth KN, Shah N, Morovati T, et al. Intravenous rt-PA is not Associated with Increased Risk of Hemorrhage in Patients with Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JT, Park MS, Yoon W, et al. Detection and significance of incidental unruptured cerebral aneurysms in patients undergoing intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Journal of neuroimaging : official journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging. 2012;22:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Silva DA, Manzano JJF, Chang HM, et al. Reconsidering recent myocardial infarction as a contraindication for IV stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2011;76:1838–1840. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccc72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasner SE, Villar-Cordova CE, Tong D, et al. Hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade after thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1998;50:1857–1859. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhakaran S, Rivolta J, Vieira JR, et al. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Among Eligible Warfarin-Treated Patients Receiving Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Acute Ischemic Stroke. ArchNeurol. 2010;67:559–563. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xian Y, Liang L, Smith EE, et al. Risks of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with acute ischemic stroke receiving warfarin and treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:2600–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergouwen MD, Casaubon LK, Swartz RH, et al. Subtherapeutic warfarin is not associated with increased hemorrhage rates in ischemic strokes treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2011;42:1041–1045. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. The Lancet. 2010;375:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grigoryan M, Tung CE, Albers GW. Role of Diffusion and Perfusion MRI in Selecting Patients for Reperfusion Therapies. Neuroimaging ClinNAm. 2011;21:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dani KA, Thomas RGR, Chappell FM, et al. Systematic Review of Perfusion Imaging With Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Heterogeneity of Acquisition and Postprocessing Parameters A Translational Medicine Research Collaboration Multicentre Acute Stroke Imaging Study. Stroke. 2012;43:563–566. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.629923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobesky J. Refining the mismatch concept in acute stroke: lessons learned from PET and MRI. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2012;32:1416–1425. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Gornbein J, et al. A Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment for Ischemic Stroke. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:914–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hills NK, Claiborne Johnston S. Why are eligible thrombolysis candidates left untreated? AmJPrevMed. 2006;31:S210–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.