Abstract

Although the insect cell/baculovirus system is an important expression platform for recombinant protein production, our understanding of insect cell metabolism with respect to enhancing cell growth capability and productivity is still limited. Moreover, different host insect cell lines may have different growth characteristics associated with diverse product yields, which further hampers the elucidation of insect cell metabolism. To address this issue, the growth behaviors and utilization profiles of common metabolites among five cultured insect cell lines (derived from two insect hosts, Spodoptera frugiperda and Spodoptera exigua) were investigated in an attempt to establish a metabolic framework that can interpret the different cell growth behaviors. To analyze the complicated metabolic dataset, factor analysis was introduced to differentiate the crucial metabolic variations among these cells. Factor analysis was used to decompose the metabolic data to obtain the underlying factors with biological meaning that identify glutamate (a metabolic intermediate involved in glutaminolysis) as a key metabolite for insect cell growth. Notably, glutamate was consumed in significant amounts by fast-growing insect cell lines, but it was produced by slow-growing lines. A comparative experiment using cells grown in culture media with and without glutamine (the starting metabolite in glutaminolysis) was conducted to further confirm the pivotal role of glutamate. The factor analysis strategy allowed us to elucidate the underlying structure and inter-correlation between insect cell growth and metabolite utilization to provide some insights into insect cell growth and metabolism, and this strategy can be further extended to large-scale metabolomic analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10616-013-9637-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cell metabolism, Factor analysis, Glutamate, Insect cell

Introduction

The insect cell/baculovirus system has been widely accepted as a feasible approach for the production of recombinant proteins during the past decade. Nevertheless, further studies to develop efficient strategies to optimize the product yield are still being pursued. In particular, the investigation of insect cell metabolism to shift the cell growth capability toward high productivity has been an important area of study. To achieve this goal, the growth regulation of insect cells and their responses to environmental changes (e.g., nutrient formulation and utilization) must be further explored. Although much effort has already been focused on investigating metabolic regulation in insect cells, sufficient information is still not available to characterize their growth behaviors (Bedard et al. 1993; Drews et al. 2000; Ferrance et al. 1993; Ohman et al. 1995). In addition, different host insect cell lines have different growth capabilities associated with diverse product yields (Benslimane et al. 2005; Hink et al. 1991; Rhiel et al. 1997; Wickham et al. 1992), which further complicates the annotation of insect cell metabolism.

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of insect cell growth and metabolism, the cell growth behaviors and utilization profiles of common metabolites among five different insect cell lines (designated Sf-21, Se-1, Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5) grown in the same culture medium were investigated. The five cell lines have varied growth capabilities and were derived from the two insect hosts, Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf) and Spodoptera exigua (Se). Sf-21 is a clone of IPLB-Sf-21AE (Vaughn et al. 1977); Se-1 was derived from neonate larvae of Spodoptera exigua, and the three other Se cell lines (Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5) were derived from whole embryos of S. exigua. To analyze these complicated metabolic data, factor analysis was introduced to detect the crucial metabolic variations among these cells. Factor analysis determines the probability that a factor, which is composed of a group of original variables that are highly correlated with each other, represents a common underlying feature hidden in the original dataset. In the present study, the concept of factor analysis could be translated to the assumption that groups of original metabolic variables with highly correlated metabolic features are likely to imply certain common metabolic phenotypes that might be biologically accountable for growth variations over the five insect cell lines. Indeed, the factor analysis approach used here identified pivotal metabolic reactions involved in the regulation of insect cell growth and metabolism. An additional experiment was conducted to confirm the results of the factor analysis through the exclusion of key metabolites from the culture media. The success of this study provides an efficient method to decipher the underlying structure and inter-correlation between cell growth and metabolite utilization, generating a better understanding of cellular metabolism for the interpretation of a variety of growth behaviors among different insect cell lines.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Primatone was purchased from Sheffield Products (Norwich, NY, USA). Tryptose was purchased from Oxoid (Ogdensburg, NY, USA). Yeastolate was purchased from Difco (Detroit, MI, USA). Other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Culture media and cell lines

Sf-21, Se-1, Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5 cells were kindly provided by Dr. JL Vaughn (United States Department of Agriculture) and maintained at 27.5 °C in 15-ml suspension cultures in 125-ml disposable shaker flasks (Corning glass, Corning, NY, USA) on a rotary shaker (New Brunswick Scientific, Enfield, CT, USA) operated at 150 rpm. Because the culture medium cost is an important factor for the successful development of large-scale insect cell culture, a low-cost, serum-free and hydrolysate-based IBL-11 medium was used in this study (Vaughn and Fan 1997), in which yeastolate and lipids are used to replace serum and two inexpensive hydrolysates (primatone and tryptose) supply most of the free amino acids in quantities equal to or exceeding those in IPL-41 medium (Weiss et al. 1981). In brief, IBL-11 medium contains inorganic salt mixture found in the IPL-41 medium, 10 g glucose/l, 2 g glutamine/l, 10 g yeastolate/l, 0.4 % (v/v) lipid mixture (Sigma, Cat. No. L5146), 5 g primatone/l, 5 g tryptose/l, 50 mg cystine/l, 250 mg methionine/l, 400 mg inosine/l, 20 mg choline/l, and 1 g Pluronic F-68/l. Because the four Se-derived cell lines were found to only proliferate efficiently in the medium with high osmolarity, the osmolarity of IBL-11 medium was adjusted to approximately 400–410 mOsm/kg by mannitol for optimal growth of all five cell lines. The glutamine-free medium used in this study was composed of IBL-11 medium without the addition of glutamine but with the same osmolarity mentioned above. Sf-21 cells were adapted to glutamine-free IBL-11 medium by serially reducing the glutamine concentration to zero over a 6-month adaptation period. All culture experiments were conducted in batch mode without fresh medium replacement, inoculated at 0.4 × 106 cells/ml, and carried out in 125-ml disposable shaker flasks (15 ml working volume) agitated at 150 rpm, 27.5 °C in IBL-11 glutamine-containing or glutamine-free media.

Analytical measurement

The total and viable cells were counted with a hemocytometer using trypan blue staining. The glucose and lactate concentrations were determined with a glucose analyzer (YSI Model 2700, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), and ammonia was measured with enzymatic assay kits purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Amino acid levels in the medium were analyzed via PITC-derivatization by Waters’ high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a Pico-Tag amino acid analysis column purchased from Waters Inc. (Milford, MA, USA).

Determination of metabolite utilization rates

The specific utilization rates of the metabolites measured in the cell cultures during the exponential growth phase were calculated as described in (Bedard et al. 1993). Briefly, the specific growth rate during exponential growth, μ (h−1), was calculated as the slope of the linear regression of cell density in the logarithmic scale versus the cultivation time (h). The metabolite utilization rate is defined as q = μ/Y, where Y (cells/10−15 mol) is the number of cells obtained per 10−15 mol of metabolite utilized and is calculated as the slope of the linear regression of the substrate concentration versus the cell density during exponential growth. Negative values in q indicate the production of the metabolites.

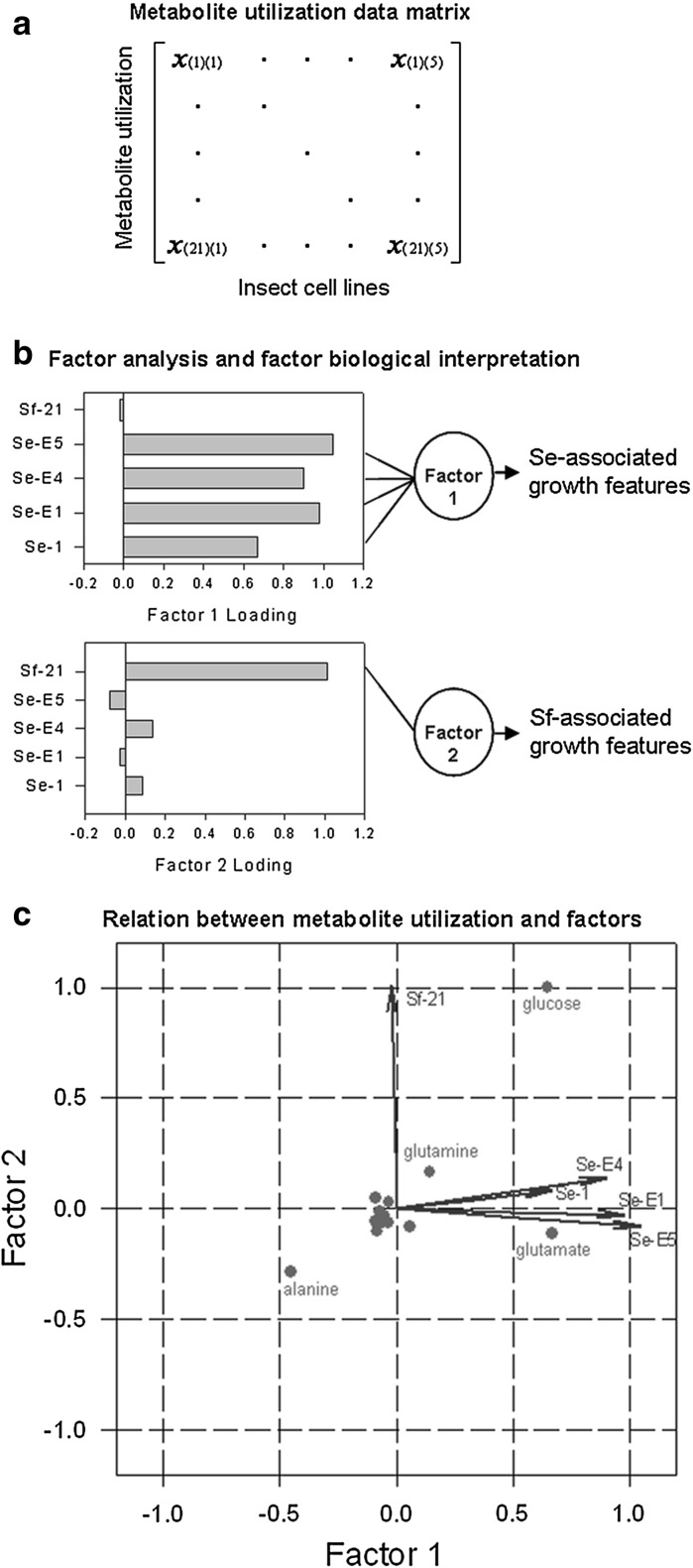

Factor analysis of metabolite utilization profile data

For the factor analysis in the present work, the metabolite utilization data are stored in a 21 × 5 matrix (X) containing a set of 21 metabolite utilization rates (variables) measured on 5 insect cell lines (samples). Before performing the factor analysis, X has to be normalized such that the mean and standard deviation of each column of X are zero and one, respectively. The detailed procedure applied to the factor analysis in this work is described in Supplementary data. The factor analysis was performed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Results

Factor analysis of metabolite utilization dataset

The growth kinetics and parameters of the five insect cell lines grown in IBL-11 serum-free medium are depicted in Fig. 1. The Se-E4 cells exhibited the fastest specific growth rate and highest maximum cell density (Fig. 1b). Conversely, the Se-1 and Sf-21 cells grew the most slowly, and the lowest maximum cell density was observed in the Sf-21 cells. The Se-E1 cells had a slower growth rate than the Se-E5 cells, but they had a higher maximum cell density than the Se-E5 cells. The utilization rates of amino acids, glucose, lactate and ammonia during the exponential growth (the first 72 h of cultivation) of the five cell lines are shown in Table 1. The growth behavior and metabolism of the different insect cell lines are highly variable. The transient utilization profiles of glucose, lactate, ammonia, alanine, glutamine, glutamate and aspartate are displayed in Fig. S1 (Supplementary data). Each of these metabolites was either extensively consumed or produced by these cells. Detailed experimental observations describing the interplay between the growth and metabolite utilization among the five cell lines can be found in the Supplementary data.

Fig. 1.

Growth behaviors of five insect cell lines. Five insect cell lines, derived from Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf-21) and Spodoptera exigua (Se-1, Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5), were grown in a serum-free but glutamine-containing IBL-11 medium, and their growth kinetics (a) and maximum cell densities (b) were recorded daily. The exponential growth phase of these cells occurred within the first 72-h cell cultivation and is clearly indicated in a. Each experiment on cell growth was performed in duplicate and all data are presented as the mean ± SD

Table 1.

Specific metabolite utilization rates during the exponential growth (0–72 h) of the five insect cell lines grown in IBL-11 medium

| Metabolite | Metabolite specific utilization rate (10−15 mol cell−1 h−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamine-containing medium | Glutamine-free medium | |||||

| Se-1 | Se-El | Se-E4 | Se-E5 | Sf-21 | Sf-21 | |

| Ammonia | −39.67 ± 3.03 | −9.63 ± 0.32 | 1.89 ± 0.12 | −1.92 ± 0.07 | 22.95 ± 1.87 | 4.81 ± 0.36 |

| Glucose | 35.97 ± 0.97 | 97.24 ± 3.48 | 70.51 ± 1.49 | 81.86 ± 3.38 | 195.90 ± 7.53 | 59.62 ± 3.12 |

| Lactate | −3.75 ± 0.02 | −9.26 ± 0.05 | 4.48 ± 0.13 | −0.48 ± 0.03 | 9.28 ± 0.19 | 5.03 ± 0.38 |

| Alanine | −81.99 ± 0.28 | −15.90 ± 0.15 | −28.32 ± 1.00 | −51.19 ± 2.78 | −37.53 ± 1.53 | 9.84 ± 0.45 |

| Arginine | 2.03 ± 0.08 | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 3.30 ± 0.15 | 3.07 ± 0.02 | 8.80 ± 0.07 | 6.54 ± 0.51 |

| Asparagine | −0.54 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 2.48 ± 0.17 | 5.06 ± 0.23 |

| Aspartate | 3.10 ± 0.16 | 24.58 ± 1.30 | 10.05 ± 0.56 | 19.59 ± 1.61 | −0.42 ± 0.02 | 6.51 ± 0.54 |

| Glutamate | 23.84 ± 0.81 | 100.11 ± 6.35 | 59.30 ± 0.91 | 95.20 ± 5.41 | −9.79 ± 0.14 | 15.62 ± 1.36 |

| Glutamine | 47.96 ± 0.56 | 13.90 ± 0.37 | 19.14 ± 1.48 | 29.64 ± 2.19 | 44.37 ± 2.21 | n.d. |

| Histidine | −1.06 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 2.82 ± 0.23 | 4.47 ± 0.21 |

| Isoleucine | −1.78 ± 0.09 | 1.42 ± 0.03 | l.97 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.08 | 5.16 ± 0.22 | 7.34 ± 0.39 |

| Leucine | −6.55 ± 0.36 | 2.80 ± 0.08 | 3.36 ± 0.21 | 2.53 ± 0.16 | 5.48 ± 0.28 | 13.68 ± 1.25 |

| Lysine | −1.56 ± 0.08 | −0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | −1.22 ± 0.02 | −4.91 ± 0.37 | −4.31 ± 0.24 |

| Methionine | −2.12 ± 0.11 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 1.84 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 1.94 ± 0.12 | 2.54 ± 0.18 |

| Phenylalanine | −1.59 ± 0.06 | 1.90 ± 0.15 | 4.53 ± 0.34 | 5.05 ± 0.33 | 2.71 ± 0.24 | 0.91 ± 0.03 |

| Proline | 1.31 ± 0.07 | −1.66 ± 0.09 | 2.42 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 12.12 ± 0.56 | 7.43 ± 0.56 |

| Serine | 2.93 ± 0.20 | 4.52 ± 0.37 | 7.43 ± 0.27 | 2.10 ± 0.01 | 18.9 ± 0.25 | 11.29 ± 0.88 |

| Threonine | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 1.62 ± 0.05 | 2.75 ± 0.11 | 2.78 ± 0.19 | 5.41 ± 0.01 | 5.30 ± 0.39 |

| Tryptophan | −1.15 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 1.87 ± 0.14 | 1.22 ± 0.04 | 1.55 ± 0.11 | 2.13 ± 0.12 |

| Tyrosine | 1.43 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | −0.94 ± 0.04 | −0.46 ± 0.03 | 4.20 ± 0.21 | 5.16 ± 0.34 |

| Valine | −3.83 ± 0.15 | −0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | −0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 1.53 ± 0.12 |

Positive values for the utilization rates indicate the consumption of metabolites, and negative values indicate the production of metabolites. Because glutamate and aspartate were consumed very rapidly in several of the five insect cell cultures (Fig. S1 g, h), their utilization rates were calculated during the initial growth phase (0–48 h). Each experiment on metabolite utilization was performed in duplicate and all data are presented as the mean ± SD

To analyze the aforementioned metabolite utilization dataset, factor analysis was used to identify the possible metabolic regulations that caused the growth variations among these cells. Because the size of the observed samples (five insect cell lines) is much less than that of the measured variables (21 metabolite utilization rates), factor analysis was performed by treating different cell lines as variables and metabolites as independent observations (samples) to investigate how the utilization of each metabolite was affected by each of the five insect cell lines (Fig. 2a). Only two factors can be obtained that likely reflect the main metabolic features in the comparative metabolic experiments. Generally, a group of variables that load (contribute) substantially to a given factor can be used to describe the factor attribution or feature to which these variables belong and thus infer the possible traits associated with that factor. Figure 2b shows that factor 1 is mainly composed of four Se-derived cell lines. By contrast, factor 2 is predominantly contributed by Sf insect cells. Based on the loading profiles of the two factors, we could reasonably conclude that the first factor represents the Se-associated growth features and that the second represents the Sf-associated ones. Factor analysis provides quantitative evidence that insect cells derived from the same insect host ought to have similar metabolic growth characteristics. Taken together, factor analysis reduced the common metabolite utilization profiles of the five insect cell lines to two underlying factors with cell type-specific growth attributes that correctly account for the interrelationships shown in our experiments.

Fig. 2.

Factor analysis of metabolite utilization dataset. a The metabolite utilization profiles are rearranged in a 21 × 5 data matrix consisting of the 21 metabolite utilization rates measured during the exponential growth of five insect cell lines. b Factor analysis maps the 21 metabolite utilization rates to a reduced-dimensional space constructed by at most two factors that likely reflect common underlying metabolic features associated with the growth of the five insect cell lines. Shown here are the loading profiles of factor 1 and 2. Biological meanings were assigned to the two factors by evaluating which cell lines contribute heavily to a given factor to infer the possible metabolic features associated with that factor. Each of the two factors is line-connected to the leading insect cell lines by which the biological interpretation of each factor is characterized and shown on the right. c A scatter plot that graphically displays both the factor loadings for each cell line and the factor scores for each metabolite. Each of the five insect cell lines is represented in this plot by a vector, and the direction and length of the vector indicates how each cell line depends on the underlying factors. The utilization rate of each metabolite is represented by a point in this plot, and its location indicates how favorable each metabolite was for the two factors. The points are scaled to fit within the unit square, so only their relative locations can be determined from the plot

Glutamate was identified as a pivotal metabolite for insect cell growth

To be able to estimate how the two cell type-specific factors affect the utilization of the 21 metabolites, both the factor loadings for individual cell lines and the new factor scores for the individual metabolites were simultaneously visualized in a single plot (Fig. 2c). Based on which cell lines are located near which factors, the first factor axis was again identified to represent the Se-associated growth characteristics and the second represented Sf-associated ones. Obviously, glutamate utilization was predominantly affected by Se-related factor 1 because it localizes almost entirely on factor 1 with a significantly high score value. Therefore, glutamate utilization can be considered as a crucial metabolic feature that may fully represent the growth characteristics of Se-derived cell lines. In addition, glutamate has a large positive score on factor 1 but a small negative score on factor 2, implying that glutamate, compared to other metabolites, is significantly consumed by Se-derived cell lines and slightly produced by Sf-21 cells. In the same way, glucose and glutamine, having contributed almost equally positive scores on factor 1 and 2, would be consumed greatly in both Se and Sf cell lines. Collectively, glutamate could be used as a metabolic marker to differentiate the growth variations between the Se and Sf cell lines.

Effect of glutamine deletion on Sf-21 cell growth and metabolism

Because glutamate is regulated by glutaminolysis (Mckeehan 1986), a fast and feasible method for further elucidating the metabolic role of glutamate is to delete one of the other components in the glutaminolysis pathway from culture medium and examine the corresponding variations in the cell growth and amino acid utilization. In the present work, glutamine, the starting metabolite of glutaminolysis, was removed from IBL-11 culture medium to perform the aforementioned nutrient deletion experiment. Because glutamine is essential for Se-1 cell growth and Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5 cells were able to grow in glutamine-free IBL-11 medium but under a highly inefficient way (i.e., the maximum cell densities for the three Se cell lines grown in glutamine-free IBL-11 medium did not exceed 2 × 106 cells/ml), only Sf-21 cells were used in this deletion study. The Sf-21 cell growth and metabolite utilization patterns in the glutamine-free culture are depicted in Fig. 3a and Table 1. The glutamine-free cell culture reached a higher maximum viable cell density of 7.8 × 106 cells/ml compared to 5.2 × 106 cells/ml in the glutamine-containing culture. The cells grown in the glutamine-containing medium consumed much more glucose than those in the glutamine-free medium during the exponential growth phase (Table 1). Particularly, the elimination of glutamine from the culture medium resulted in the significant consumption of glutamate instead of production in the glutamine-containing culture (Fig. 3b; Table 1). In addition, alanine was also slightly consumed in the glutamine-free culture, but it was produced in the glutamine-containing culture (Fig. 3c; Table 1). Again, the utilization of glutamate was found to play a key role in regulating Sf-21 cell growth. In summary, Sf-21 cells consumed significant quantities of glutamate and operated more efficiently in glutamine-free medium, as evidenced by reduced glucose consumption, no alanine formation, less ammonia accumulation, and a higher maximum cell density.

Fig. 3.

Effect of glutamine deletion on Sf-21 cell growth and metabolism. Sf-21 cells were grown in glutamine-containing and glutamine-free IBL11 media to investigate how the removal of glutamine from the culture media affects insect cell growth and metabolism. The viable cell density (a) and concentrations of glutamate (b) and alanine (c) in the culture supernatants were recorded daily. Each experiment on cell growth and metabolite utilization was performed in duplicate and all data are presented as the mean ± SD

Discussion

As mentioned above, those cells (Se-E1, Se-E4 and Se-E5) that significantly utilized glutamate and presented substantial consumption of glutamine grew faster than those that mainly utilized glutamine and displayed less uptake (Se-1) or production (Sf-21) of glutamate. In addition, the consumption of glutamate was always more dominant than the consumption of glutamine in those fast-growing cells. Unlike most animal cells (e.g., hybridoma cells), glutamine does not seem to be an essential nutrient for the growth of insect cells, except for Se-1 cells, and glutamine uptake associated with the significant consumption of glutamate seems to enhance insect cell growth. Moreover, even without glutamine in the culture medium, glutamate was instead significantly consumed in Sf-21 cells with better growth capability than their counterparts grown in glutamine-containing medium. The similar results have been also reported by Ohman et al. (1995, 1996), in which Sf-9 and Sf-21 cells were found to be fully able to grow in a glutamine-free medium, and the amount of Sf-9 cells produced per glutamine consumed in fed batch cultures was 50–100 times higher during glutamine limitation than during glutamine excess. Moreover, the consumption of glutamate was significantly increased in the glutamine-limited fed batch culture. Based on these observations, glutamate is likely to possess superior metabolic advantages than glutamine, enabling insect cells to grow faster.

According to the literature (Doverskog et al. 2000; Drews et al. 2000), the glutamine uptake in cultured Sf-9 cells may be mediated by NADH-dependent glutamate synthase (GOGAT), which stimulates glutamine along with α-ketoglutarate to form glutamate, where alanine is produced by alanine transaminase [i.e., glutamine + α-ketoglutarate + NAD(P)H → 2 glutamate + NAD(P)]. Glutamate synthase has been detected in the insect silkworm Bombyx mori (Hirayama et al. 1998) and in Sf-9 cells (Drews et al. 2000) and is also likely active in the Sf-21 and Se-derived cells used in this study. Because α-ketoglutarate is a TCA cycle intermediate and NAD(P)H can yield ATP by oxidative phosphorylation, both are important metabolites required for energy production and cell growth. Thus, their consumption for glutamate biosynthesis by GOGAT would reduce α-ketoglutarate flux into the TCA cycle and lower the NAD(P)H level for ATP production, which would lead to impaired cell growth. In other words, direct glutamate uptake by insect cells can avoid the inefficient conversion of glutamine into glutamate by GOGAT and result in more energy production and improved cell growth. Indeed, because there is no need for the additional conversion of glutamine into glutamate in glutamine-free Sf-21 cell culture, the cells grew more efficiently to reach a higher maximum cell density than those grown in glutamine-containing medium. The above explanation may be further supported by a previous study, in which Sf-9 cells grown in a glutamine-limited fed batch culture exhibited a more efficient energy metabolism and enhanced cellular yield (Ohman et al. 1995).

The current study integrated up to five different insect cell metabolic datasets with factor analysis for the identification of growth-determining metabolite markers. This work successfully demonstrates a simple and efficient multivariate analysis for small-scale metabolic profiling data. Moreover, the same strategy can be extended to other metabolomics studies.

Electronic supplementary material

References

- Bedard C, Tom R, Kamen A. Growth, nutrient consumption, and end-product accumulation in Sf-9 and BTI-EAA insect cell cultures: insights into growth limitation and metabolism. Biotechnol Prog. 1993;9:615–624. doi: 10.1021/bp00024a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benslimane C, Elias CB, Hawari J, Kamen A. Insights into the central metabolism of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf-9) and Trichoplusia ni BTI-Tn-5B1-4 (Tn-5) insect cells by radiolabeling studies. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:78–86. doi: 10.1021/bp049800u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doverskog M, Jacobsson U, Chapman BE, Kuchel PW, Haggstrom L. Determination of NADH-dependent glutamate synthase (GOGAT) in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells by a selective 1H/15N NMR in vitro assay. J Biotechnol. 2000;79:87–97. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews M, Doverskog M, Ohman L, Chapman BE, Jacobsson U, Kuchel PW, et al. Pathways of glutamine metabolism in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells: evidence for the presence of the nitrogen assimilation system, and a metabolic switch by 1H/15N NMR. J Biotechnol. 2000;78:23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00231-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrance JP, Goel A, Ataai MM. Utilization of glucose and amino acids in insect cell cultures: quantifying the metabolic flows within the primary pathways and medium development. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;42:697–707. doi: 10.1002/bit.260420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hink WF, Thomsen DR, Davidson DJ, Meyer AL, Castellino FJ. Expression of three recombinant proteins using baculovirus vectors in 23 insect cell lines. Biotechnol Prog. 1991;7:9–14. doi: 10.1021/bp00007a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama C, Saito H, Konno K, Shinbo H. Purification and characterization of NADH-dependent glutamate synthase from the silkworm fat body (Bombyx mori) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckeehan WL. Glutaminolysis in animal cells. In: Morgan MJ, editor. Carbohydrate metabolism in cultured cells. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 111–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ohman L, Ljunggren J, Haggstrom L. Induction of a metabolic switch in insect cells by substrate-limited fed batch cultures. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:1006–1013. doi: 10.1007/BF00166917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman L, Alarcon M, Ljunggren J, Ramqvist A-K, Haggstrom L. Glutamine is not an essential amino acid for Sf-9 insect cells. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:765–770. doi: 10.1007/BF00127885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhiel M, Mitchell-Logean CM, Murhammer DW. Comparison of Trichoplusia ni BTI-Tn-5B1-4 (high five) and Spodoptera frugiperda Sf-9 insect cell line metabolism in suspension cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1997;55:909–920. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970920)55:6<909::AID-BIT8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn JL, Fan F. Differential requirements of two insect cell lines for growth in serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1997;33:479–482. doi: 10.1007/s11626-997-0067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn JL, Goodwin RH, Tompkins GJ, McCawley P. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae) In Vitro. 1977;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SA, Smith GC, Kalter SS, Vaughn JL. Improved method for the production of insect cell cultures in large volume. In Vitro. 1981;17:495–502. doi: 10.1007/BF02633510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham TJ, Davis T, Granados RR, Shuler ML, Wood HA. Screening of insect cell lines for the production of recombinant proteins and infectious virus in the baculovirus expression system. Biotechnol Prog. 1992;8:391–396. doi: 10.1021/bp00017a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.