Abstract

The genome of the cytopathogenic (cp) bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) JaCP contains a cellular insertion coding for light chain 3 (LC3) of microtubule-associated proteins, the mammalian homologue of yeast Aut7p/Apg8p. The cellular insertion induces cp BVDV-specific processing of the viral polyprotein by a cellular cysteine protease homologous to the known yeast protease Aut2p/Apg4p. Three candidate bovine protease genes were identified on the basis of the sequence similarity of their products with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae enzyme. The search for a system for functional testing of these putative LC3-specific proteases revealed that the components involved in this processing have been highly conserved during evolution, so that the substrate derived from a mammalian virus is processed in cells of mammalian, avian, fish, and insect origin, as well as in rabbit reticulocyte lysate, but not in wheat germ extracts. Moreover, two of these proteases and a homologous protein from chickens were able to rescue the defect of a yeast AUT2 deletion mutant. In coexpression experiments with yeast and wheat germ extracts one of the bovine proteases and the corresponding enzyme from chickens were able to process the viral polyprotein containing LC3. Northern blots showed that bovine viral diarrhea virus infection of cells has no significant influence on the expression of either LC3 or its protease, bAut2B2. However, LC3-specific processing of the viral polyprotein containing the cellular insertion is essential for replication of the virus since mutants with changes in the LC3 insertion significantly affecting processing at the LC3/NS3 site were not viable.

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) is classified as a member of the genus Pestivirus within the family Flaviviridae (14). Pestiviruses represent enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses with a genome of about 12.3 kb. The genomic RNA contains one long open reading frame that is translated into a polyprotein. Processing of the polyprotein by cellular and virus-encoded proteases gives rise to at least 11 proteins, arranged in the polyprotein in the order NH2-Npro-C-Erns-E1-E2-P7-NS2/3-NS4A-NS4B-NS5A-NS5B-COOH. C, Erns, E1, and E2 are present in pestivirus virions, whereas the other polypeptides represent nonstructural proteins (25, 34). As also reported for the other pestiviruses, two BVDV biotypes that exhibit either a cytopathogenic (cp) or a noncytopathogenic (noncp) phenotype are known. The two biotypes are consistently found in calves that come down with fatal mucosal disease (MD), and it is widely accepted now that the de novo generation of a cp variant of a noncp BVDV within an animal persistently infected with the latter virus represents one path to MD (46).

The cp viruses are derived from noncp viruses by various mutations (21, 34). Typical genome alterations specific for autonomously replicating cp BVDV are a set of point mutations, duplications, and rearrangements of viral sequences or the insertion of various cellular sequences, often flanked by large duplications of viral sequences. Some well-known cellular insertions are sequences coding for ubiquitin, several ubiquitin-like proteins, and part of a chaperon named JIV (2, 28, 31, 32, 37, 40). The cp BVDV-specific genome alterations lead to expression of nonstructural protein NS3 by inducing an additional cleavage of the polyprotein at the amino terminus of NS3. Naturally occurring noncp BVDVs express the fusion protein NS2-3, but further processing giving rise to NS3 was not detected. The functional correlation between the generation of NS3 and the induction of cell death by cp BVDV is still questionable since NS3 expression is not necessarily connected with a cp phenotype (4, 33, 38).

The cp BVDV isolate JaCP represents a member of a whole set of cp BVDVs isolated from one animal that came down with MD (8). All the viruses of this set contain an insertion in their genomes that is derived from a cellular mRNA coding for light chain 3 (LC3) of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). In the genome of JaCP, the cellular sequence is flanked by two different stretches of duplicated viral RNA, the larger one of which codes for the nonstructural protein NS3 and sequences downstream thereof. It was shown before that the cellular insertion induces the cp BVDV-specific cleavage of the viral polyprotein at the amino terminus of NS3 (29). LC3 represents a polypeptide of about 16.4 kDa that copurifies with microtubules from different sources (26). The rat LC3 mRNA was found to contain an open reading frame capable of encoding a protein of 141 amino acids. Proteins homologous to LC3 from rats were found not only in different mammalian cells but also in, e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans, and plants (22). The function of LC3 remained obscure until it was recognized by analysis of yeast mutants that Aut7/Apg8, the yeast LC3 homologue, is necessary for autophagy, a process of bulk protein degradation occurring under starvation conditions (22). Further analyses revealed that the gene product Aut7p/Apg8p is found on the surfaces of autophagic vesicles (18). Similar results were also found for rat LC3, indicating that this protein and its homologues represent part of a general pathway leading to formation of autophagosomes (17). However, LC3 and its homologues in other species are not only necessary for autophagy but also seem to play a role in a variety of processes, e.g., fibronectin translation regulation (51), multiple membrane trafficking processes (23), the Notch signaling pathway (47), and the regulation of Sos1-Rac1 signaling by binding to the DH domain of Sos1 (9).

Interestingly, mammalian LC3 and yeast Aut7p/Apg8p were found to exist in different forms (17, 19). One form of the protein was present in the cytosol, and it was first shown for yeast Aut7p/Apg8p that this form of the protein was obtained from the primary translation product by carboxy-terminal processing by the cysteine protease Aut2p/Apg4p (19). Subsequently, conjugation with the amino group of phosphatidylethanolamine occurs, leading to a membrane-bound form of Aut7p/Apg8p found on the surfaces of autophagosomes (16). Similar to Aut7p/Apg8p, the mammalian LC3 is processed proteolytically to form LC3-I and subsequent conjugation leads to LC3-II, which represents the membrane-bound form of LC3 (17).

The elucidation of the processing of LC3 and Aut7p/Apg8p in the mammalian and yeast cells, respectively, was facilitated by our data published on BVDV strain JaCP (29). Amino-terminal sequencing of the carboxy-terminal cleavage product NS3 revealed that cleavage occurs exactly at the position where cellular and viral sequences were fused. The respective amino acid of the LC3 sequence corresponds to glycine 120. A glycine is also present at the equivalent position of yeast Aut7p/Apg8p (position 116) and several other LC3 homologues (19, 22, 36, 41). Moreover, threonine and phenylalanine, the residues at positions 118 and 119 of LC3, are also conserved in most of the sequences, whereas the length and the sequence of the peptide downstream of glycine 120 are highly variable. It therefore was predicted that the shorter versions of LC3 and Aut7p/Apg8p are generated by cleavage at glycine 120. This prediction has recently been verified for the yeast protein (19). In addition to the data concerning the cleavage of the viral LC3/NS3 fusion at glycine 120 (29) it was shown for the mammalian system that a change of glycine 120 to alanine interferes with the conversion of LC3 to LC3-I in the rat system (17).

We identify here proteases in bovine and chicken cells that show homology to yeast Aut2p/Apg4p. One of the mammalian proteases cleaves the LC3/NS3 fusion expressed by BVDV JaCP as well as the bovine LC3 precursor. Moreover, the viral LC3/NS3 fusion protein is cleaved in a variety of heterologous systems from mammals to insects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

MDBK cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). BHK-21 cells were kindly provided by T. Rümenapf, University of Gießen, Gießen, Germany. Chicken embryonic fibroblasts (HFB-R) were obtained from the Collection of Cell Lines in Veterinary Medicine at the Federal Research Center of Virus Diseases of Animals, Insel Riems, Germany (CCLV no. Rie0182). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (MEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and nonessential amino acids. Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells were kindly provided by F. Käsermann and C. Kempf (University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland) and were grown in MEM supplemented with nonessential amino acids and 10% FCS. Fish cells (RTG) were kindly provided by P. Enzmann, Federal Research Center for Virus Diseases of Animals, Tübingen, Germany, and grown in MEM with 0.014 M HEPES and 10% FCS.

Cloning of putative protease genes.

Total RNA of MDBK cells or chicken embryonic fibroblasts was isolated with the RNeasy kit according to the protocol proposed by the supplier (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). About 2 μg of the purified RNA was used for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was carried out at 50 (bAut2A) or 53°C (other proteases) for 30 min. Thereafter, the RNA-DNA hybrid was denatured at 95°C for 15 min and the DNA was amplified in 30 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 53°C, 60 s at 72°C). Primer concentration in the reaction mixture was 0.6 μM. The reaction mixture contained 10% Q-Solution (Qiagen). Primers for this round of PCR were as follows: bAut2A, Aut 1 (sense; AGGATGACAGCTGGAGAATGGAG) and AutREVIII (antisense; CAGACCTTCAAGTTGAGTTCCCAG); bAut2B1, +Uff (XhoI; sense; GGGGCTCGAGAGCGAAGATGGACGCAGCTAC) and −war (HindIII; antisense; GGGGAAGCTTGGCCGAAGCCGCTCTGCGCG); bAut2B2 and cAut2B,+Uff (XhoI; sense; GGGGCTCGAGAGCGAAGATGGACGCAGCTAC) and NDAII (antisense; GGGCTCGAGTCAAAGGGACAGGATTTCAAG). One-fiftieth portions of the different RT-PCR products were used as templates in a second PCR with a second pair of primers. Conditions for the PCR were 30 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 53 or 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C (annealing at the lower temperature was done for bAut2B1; for all other proteases the annealing temperature was 55°C). PCR was performed with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany), the buffer conditions recommended by the supplier, and a primer concentration of 0.4 μM. Primers for this round of PCR were as follows: bAut2A, M2PB (sense; GGGAAGCTTATGGAGTCAGTTTTATCCAAGTATG) and REVN2PB (antisense; GGGCTCGAGGTTGAGTTCCCAGTATCCTATATG); bAut2B1, AD1 (EcoRI; sense; GGGGAATTCATGGACGCAGCTACCCTTACCTACG) and REVN1PB (XhoI; antisense; GGGCTCGAGGCTTCTGGGCTCTGAACTG); bAut2B2 and cAut2B, M1PB (sense; GGGAAGCTTATGGACGCAGCTACCCTTACCTACG) and NDAII (antisense; GGGCTCGAGTCAAAGGGACAGGATTTCAAG). The amplified cDNA fragments were cut with EcoRI/XhoI or HindIII/XhoI (bAut2B1 gene or other protease genes, respectively) and ligated with equivalently cleaved pYES2 vectors (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). The amplification and cloning of the sequence coding for the chicken protein cAut2B were carried out as described for the sequence coding for the bovine homologue bAut2B2. The pYES2 plasmid contains a GAL1 promoter for expression in yeast and a T7 promoter allowing in vitro transcription and translation.

Standard procedures, such as restriction, end filling with Klenow DNA polymerase, dephosphorylation with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase, ligation, and cloning, were done essentially as described before (42). Restriction and modifying enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Schwalbach, Germany), Amersham (Freiburg, Germany), Invitrogen, and Roche Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). The sequences of the different cDNA fragments were determined with the Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) and analyzed with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). Sequencing primers were as follows: bAut2A, yes seq (ACCTCTATACTTTAACGTCAAGG), yes Rev (GGAGGGCGTGAATGTAAGCGTG), Aut2 (CACTTGGGAAGGGACTGGAGCTG), and AutRevI (CAGCTCCAGTCCCTTCCCAAGTG); bAut2B1, bAut2B2, and cAut2B, yes seq, yes Rev, JF +1 (GTGGTGATGGCGGATATCAGGAG), JF +2 (GACGTCAACGCGGCCTACGCG), and JFRev2 (GGAGTAGCAGCTGTCCTTCCTG). Computer analysis of sequence data was performed with the Genetics Computer Group software (7). The alignment of the different protease amino acid sequences was established with the Lasergene software (program Megalign; DNASTAR).

Establishment of substrate constructs.

The construct pEx/JaCP, which codes for the NS2/LC3/NS3 fusion protein, has been described before (only part of the NS2 gene was present in the construct; the LC3 insertion codes for amino acids 5 to 120 of the bovine LC3) (29). Based on pEx/JaCP, the sequence coding for NS2/LC3Δ/NS3 was obtained. A 5′ fragment was generated by PCR with primers LC3-1 and LC3-9 (template pEx/JaCP); a 3′ fragment was generated the same way with primers X and B30RII. To obtain pEx/JaCPΔ, the 5′ fragment was cut with BamHI and ApaI and inserted together with the 3′ fragment cleaved with ApaI and HpaI into pEx/JaCP restricted with BamHI and HpaI.

Starting with these constructs the different expression plasmids were established. For in vitro translation analyses, fragments were amplified by PCR from pEx/JaCP and pEx/JaCPΔ with primers pskpepg and pskrevns3 by using the Pfu polymerase according to the method described by the supplier (Stratagene). The PCR fragments were cut with XhoI and HindIII and inserted into pSKII− (Stratagene) cut with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmids code for proteins composed of the 20 carboxy-terminal amino acids of NS2, the respective LC3-derived sequence, and the 96 amino-terminal amino acids of NS3 and were termed pSK-LC3 and pSK-LC3Δ. Similarly, pEx/JaCP and pEx/JaCPΔ served as templates for PCR amplification with primers LexA and LexARev and the cloning of the resulting fragments, after treatment with EcoRI and XhoI, into pLexA (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany) cut with the same enzymes, resulting in pLex-B/LC3 and pLex-B/LC3Δ, respectively. These plasmids contain the 168 carboxy-terminal amino acids of NS2, the respective LC3-derived sequence, and the 96 amino-terminal amino acids of NS3.

Starting with the pLexA constructs the Sindbis virus expression constructs were generated by cleavage with BamHI and EcoRI, end filling with Klenow polymerase, and religation, followed by HindIII/XhoI cutting and ligation with pYES2 treated with the same enzymes. The pYES2 constructs were cut with HindIII, end filled with Klenow polymerase, cut with SphI, ligated with pSinRep5 (Invitrogen), cut with XbaI, end filled, and then cut with SphI. All constructs were verified by nucleotide sequencing (Seq.Primer: Jas Ins I, Jas Ins II, and B 22.1R).

To obtain the bovine LC3 gene, an LC3 cDNA clone (clone 16/5) was isolated from a commercially available cDNA library (bovine spleen; λ-Uni-Zap-XR; Stratagene) according to standard procedures (42) and the recommendation of the supplier. Clone 16/5 contained the complete LC3-coding sequence and served as a template for a PCR with primers TAAS4 and TAASEU. The PCR fragment was cut with HindIII, end filled with Klenow polymerase, and then cut with XhoI and ligated together with a second PCR fragment (cut with NcoI and XhoI) into pCITE (Novagen/AGS, Heidelberg, Germany) that had been cleaved with NotI, end filled with Klenow polymerase, and then cut with NcoI. This second PCR fragment codes for a tag sequence (pep6) derived from the C terminus of BVDV NS2 and was obtained by PCR with pEx/JaCP and primers Alpha6S and Alpha6AS. The resulting pCITE plasmid was cut with XhoI, dephosphorylated, and ligated with phosphorylated oligonucleotides FRICKE01 and FRICKE02, which code for a VP5 tag. The insert released by the above-described XhoI cleavage was afterwards inserted back into the VP5-containing vector cut with XhoI and dephosphorylated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase. The resulting plasmid was cut with NcoI/PstI, treated with Klenow polymerase to generate blut ends and ligated with a Bluescript pSK II plasmid, cut with XhoI and HindIII, and end filled with Klenow polymerase. The resulting plasmid codes for the entire LC3 sequence from bovine cells flanked by an amino-terminal pep6 tag and carboxy-terminal VP5 and six-His tags. Primers were as follows: LC3-1 (GGGGGATCCTAAGGAAAACCTTC), LC3-9 (GGGGGGCCCCTCGCTTTCATACACTTCAC), X (r.10) (GGGGGATCCGACTTTTGGAGGGCCCGCCGTG), B30RII (CCCCTGTTCATGCTGGTTATCTTCTTGACCAT), Pskpepg (GGGCTCGAGATGGTAGGCAACCTAGGAG), Pskrevns3 (GGGAAGCTTGTTAACC TGTTGTTGCTCTGG), FRICKE01 (TCGAGGGTAAGCCTATCCCTAACCCTCTCCTCGGTCTCGATTCTACGG), FRICKE02 (TCGACCGTAGAATCGAGACCGAGGAGAGGGTTAGGGATAGGCTTACCC), Alpha6S (GGGCCATGGTAGGCAACCTAGGAGAGG), Alpha6AS (GGGCTCGAGCCATCCTAGGTGTTCTAGATCAC), TAAS4 (GGGGCTCGAGATGCCGTCCGAGAAAACCTTC), TAASEU (GGGAAGCTTCACAGATAATTTCATTCCAAAAGTC), LexA (GGGGAATTCATGGAAGAAGAAGAGAGCAAGG), and LexA Rev (GGGCTCGAGTCAGTTAACCTGTTGTTGCTCTGG). Sequencing primers for pLex constructs were B22.1R (GTTGACATGGCATTTTTCGTG), B4700 (TCTGGAAGGTTGAGGAACCT), JasInsI (GGGATTTTGGTAGGATGC), and JasInsII (GTAGAAGATGTCCGACT).

Protein expression in the Sindbis virus system.

The pSinRep5 plasmid (Invitrogen) and the helper plasmid DH-EB (44) contain SP6 RNA polymerase promoters for in vitro transcription. About 2 μg of DNA was linearized with XhoI (DH-EB) or NotI (pSinRep5 plasmids), purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, and used as a template for in vitro transcription with SP6 RNA polymerase (Amersham) under conditions suggested by the supplier. The RNA was purified by treatment with DNase I (Amersham), centrifugation through a Sephadex G50 spun column (42), and phenol extraction.

BHK cells (107) were transfected in suspension by electroporation with two pulses (200 Ω, 25 μF, 1,500 V, 0.4-cm cuvettes; Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad, Münich, Germany) and a mixture of the recombinant pSinRep5 and the DH-EB RNAs (about 0.5 μg each) and seeded into 35-mm-diameter tissue culture plates. At 20 h posttransfection, the supernatant of the culture was harvested and used for infection of the different cells. Infected cells were incubated at 20°C (RTG) or 37°C (other cells) for about 4 days (RTG) or 26 h (other cells) and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed for 5 min at 70°C in 150 μl of cracking buffer (stock solution consisting of 8 M urea, 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.4 mg of bromphenol blue/ml, and 5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], to which, before use, 10 μl of β-mercaptoethanol, 50 μl of a 100 mM solution of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] in isopropanol, and 70 μl of protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche; dissolved in water as described by the manufacturer] per ml of stock solution were added). Thereafter, 80 μl of glass bead suspension (425 to 600 μm; Sigma, Taufkrichen, Germany) was added, and the solution was mixed on a vortex and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatant was boiled for 3.5 min and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

Protein expression in yeast.

For the protein expression experiments a yeast egy48 mutant defective in Aut2p expression was used. This mutant was generated by chromosomal deletion of AUT2. A PCR fragment consisting of the kanamycin resistance gene flanked by up- and downstream sequences of AUT2 was generated with oligonucleotides aut2kan1 (CGGTTACAACAATTTATGCTTATATTTGACTCTGCGATTACAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC) and aut2kan2 (AAACAAGTATATATGCTTATGAACTAGTGAATTCCTTACAGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG) and plasmid pUG6 (13). Chromosomal replacement of AUT2 with this fragment in egy48 (Clontech) yielded YCV3 and was confirmed by Southern blotting. For immunological detection of proaminopeptidase I (pAPI) maturation and for checking for vacuolar accumulation of autophagic bodies the yeast strain YTL9 (MATa his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 ura3 aut2::KAN) (22) was used.

For the protein expression experiment the yeast cells were grown overnight to the late-stationary-growth phase in synthetic complete (SC) medium (prepared as described in reference 1) containing 2% galactose. The cells were washed twice with water and starved for 4 h in 1% potassium acetate at 30°C while being shaken (180 rpm). Then the cells were washed with cold water, lysed by addition of 150 μl of cold lysis mixture (925 μl of 2 M NaOH, 75 μl of β-mercaptoethanol), and put on ice for 10 min. Afterwards 150 μl of cold 50% trichloroacetic acid was added and the cells were again put on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation (13,800 × g, 10 min) the pellet was washed twice with 500 μl of acetone and dissolved in Laemmli buffer.

For detection of vacuolar accumulation of autophagic bodies the cells were grown to the late-stationary-growth phase as described above and washed twice with water. For starvation the cells were then shifted to SD(-N) (1.7 g of yeast nitrogen base/liter without amino acids and ammonium sulfate [Difco, Detroit, Mich.], 2% glucose) containing 1 mM PMSF (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 4 h at 30°C while being shaken (180 rpm). The cells were visualized with Nomarski optics using a Zeiss Axioskop Plus equipped with an Axiocam digital image system.

In vitro translation.

RNA for in vitro translation was prepared by in vitro transcription with 2 μg of the respective cDNA construct that had been linearized with EcoRV (pSK-cLC3 constructs), HindIII (other substrate constructs), or XhoI (pYES-protease constructs) and purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl of transcription mixture (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]; 6 mM MgCl2; 2 mM spermidine; 10 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM each ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP; 10 mM dithiothreitol; 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml) with 50 U of T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of 15 U of RNAguard (Amersham). After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, 7.5 U of DNase (RNase free; Amersham) was added and incubation at 37°C was continued for 30 min. Thereafter, the reaction mixture was passed through a Sephadex G-50 spun column (42) and further purified by phenol extraction and ethanol purification. About 1/10 of the transcribed RNA was used for translation with either rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) or wheat germ extract (WG) (Promega, Mannheim Germany) and with [35S]methionine for labeling the translation products. The proteins were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

Antisera.

The LexA antibodies directed against the BD tag were purchased from Clontech. Rabbit anti-mouse antibodies and goat anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany). The antisera directed against the Aut2p/Apg4p-homologous bovine proteases were raised against peptides with sequences derived from conserved regions of the proteins. For each protease type two different peptides coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (as described in reference 10) were used for immunization of rabbits (conducted by Charles River WIGA, Sulzfeld, Germany). Peptides (sequences in one-letter code) were as follows: bAut2A, Peptid F17 (GRDWNWEKQKEQPKEY) and Peptid F18 (DSTEQLEEFDLEEDFEILSI); bAut2B/cAut2B, Peptid F19 (DAATLTYDTLRFAEFEDFPETS) and Peptid F20 (DWRWTQRKRQPDSYC). The bAut2B antiserum recognizes only the F20 sequence since it did not react with the F19 peptide in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Detection of proteins by Western blotting.

The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, the gel was rinsed in transfer buffer for 30 min, and then the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) for 2 h at 100 mA in a semidry blot apparatus as recommended by the manufacturer (TE 80; Hoefer/Amersham, Freiburg, Germany). The transfer membrane was then incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 [PBS-T] and 2.5% low-fat milk powder). Afterwards, the solution was replaced by PBS-T and the first antibody and incubated for about 16 h. Then, the membrane was washed three times with PBS-T and incubated for 2 h with the second antibody in PBS-T. After three cycles of washing with PBS-T the membrane was incubated with the Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, St. Augustin, Germany) as recommended by the supplier, and bound antibodies were detected by exposure to BIOMAX MR films (Kodak, Stuttgart, Germany). Antibody dilutions in PBS-T were as follows: LexA antibody, 1:15,000; horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antiserum, 1:5,000; antiprotease sera: 1:5,000; hoseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antiserum, 1:5,000.

For detection of pAPI maturation, the yeast samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was coated overnight with 10% nonfat dry milk in TBST buffer (20 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), washed three times with TBST, and then incubated for 1 h with rabbit antiserum against pAPI (3) (diluted 1:5,000 in TBST), additionally washed three times for 10 min with TBST, and then incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit antiserum (Medac, Hamburg, Germany; diluted 1:5,000 in TBST with 1% milk). After six washes with TBST, chemiluminescence was detected with the ECL detection kit (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany).

Establishment of full-length cDNA clones with mutated LC3 insertions and tests for replication of the RNAs transcribed thereof.

BVDV sequences with mutated LC3 insertions were established by PCR with pEx/JaCP, primer Ol-ad0, and various primers containing the desired mutation. The resulting fragments were cut with BamHI and PstI and inserted into pEx/JaCP cut with BamHI and HpaI together with a second PCR fragment established with primers Ol-PSTSI and Ol-B30RII and cut with PstI and HpaI. Starting with the resulting mutated pEx/JaCP plasmids, the full-length clones were established and used for in vitro transcription. The resulting genome-like RNA was used for transfection of MDBK cells with DEAE-dextran as described before (29). Productive transfection and viral replication were detected either by observation of cytopathic effect, RNA isolation, and Northern blotting or RT-PCR analysis or by immunofluorescence when no helper virus was used. RNA was prepared from the transfected cells with the Trifast reagent (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). RT-PCR was done with the One Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) and primer pair Ol-JasInsII-Ol-B30RII or Ol-B21.1-Ol-B30RII. The amplified fragments were sequenced as described above.

Northern blotting with probes labeled by nick translation was conducted as described before (31). In addition to the BVDV NCP1 probe described in reference 31, the inserts of the protease plasmids or the cloned bovine LC3 sequence described above was used. A chicken actin probe served as a control. Primers were as follows: Ol-B21.1 (TCATGGTAGGCAACCTAGGAG), OL-AD0 (GGGGGATCCTAAGGAAAACCTTC), Ol-Cys_P1 (GGGCTGCAGGCCCGCAAAAAGTCTCCTG), Ol-Cys_P2 (GGGCTGCAGGCCCTCCACAAGTCTCCTG), and Ol-Cys_P3 (GGGCTGCAGGCCCTCCAAAACACTCCTGAG).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the different protease genes were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: bAut2A, AY5749; bAut2B1, AY5750; bAut2B2, AY5751; cAut2B, AY5752. The sequence of the bovine LC3-coding cDNA was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY5753.

RESULTS

Cloning of mammalian and avian sequences homologous to yeast AUT2/APG4.

The pestivirus BVDV JaCP expresses a fusion protein containing a fragment of the bovine LC3 and viral nonstructural proteins NS2 and NS3 (NS2/LC3/NS3). It was shown before that this protein is processed in an LC3-dependent manner at the carboxy terminus of the LC3 sequence. This processing was also observed after in vitro translation in RRL (29). Studies conducted with known protease inhibitors revealed a 67% reduction of cleavage efficiency in the presence of TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone), a known cysteine protease inhibitor. Similarly, N-ethylmaleimide, another cysteine protease inhibitor, reduced processing efficiency considerably (not shown). Thus, in analogy to the situation in yeast it could be hypothesized that a cellular cysteine protease responsible for processing cellular LC3 cleaves the viral protein containing the LC3 sequence. This protease would represent a functional homologue of yeast Aut2p/Apg4p.

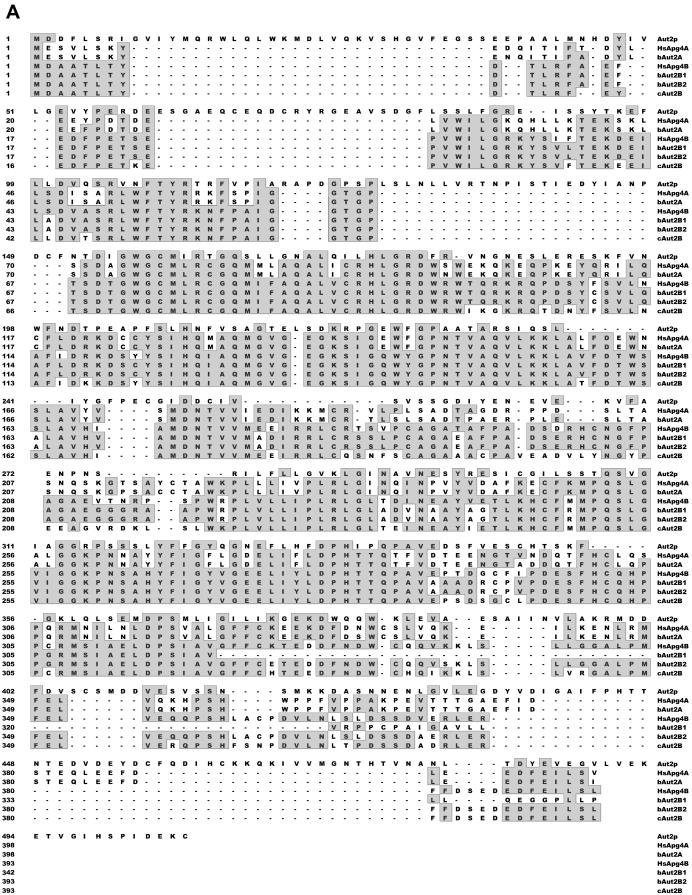

Two human sequences with homology to yeast Aut2p had already been identified in databases (19). From these sequences and those of other putative Aut2 homologues, primer sequences were deduced for amplification of Aut2-homologous sequences. Three different bovine cDNA sequences were amplified and cloned in pYES2. Sequencing revealed that two of the three proteins were highly homologous to each other, with a distinct region of dissimilarity located in the carboxy-terminal part of the sequence. These two sequences were named bAut2B1 and bAut2B2. The most obvious difference between the two sequences is a deletion of 52 amino acids in bAut2B1 (Fig. 1A). The third sequence was clearly different from the two and was designated bAut2A. The bovine sequences bAut2A and bAut2B form clusters with the corresponding human sequences HsApg4A and HsApg4B, respectively. To obtain a homologous sequence from a phylogenetically rather unrelated species a sequence from chicken cells that shows highest similarity with HsApg4B and bAut2B (Fig. 1B) was amplified and was named cAut2B. The HsApg4B and cAut2B proteins are equivalent to variant bAut2B2 since they do not contain the deletion present in bAut2B1. The bAut2B and cAut2B sequences and the corresponding human HsApg4B sequence showed a slightly higher homology to the yeast Aut2p/Apg4p sequence than those of the A series but in general the sequence similarity between the higher eukaryotic sequences and the yeast protease is rather low except for several stretches of amino acids with high homology.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of Aut2p/Apg4p-homologous sequences. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of the bovine (bAut2A, bAut2B1, and bAut2B2) and chicken (cAut2B) Aut2p/Apg4p homologues with yeast Aut2p/Apg4 and two human homologues (HsApg4A and HsApg4B [19]). Sequence homology is indicated by gray boxes; a hyphen indicates that the respective sequence has a deletion of one amino acid at the position. The total lengths in amino acids of the aligned sequences are as follows: Aut2p, 506; HsApg4A, 398; bAut2A, 398; HsApg4B, 393; BAut2B1, 342; bAut2B2, 393; cAut2B, 393. (B) Dendritic diagram comparing the amino acid sequences in panel A. The diagram was generated with the Megalign program (Lasergene software; DNASTAR).

Search for a system to test the putative proteases for their ability to cleave LC3.

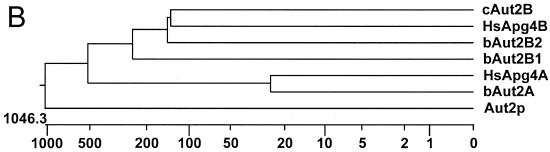

Previous experiments provided evidence that the processing of our substrate composed of LC3 and viral sequences (NS2/LC3/NS3) occurred after transient expression in BHK cells (29). To be able to test for the activity of our cloned candidate proteases, a simple expression system that showed no intrinsic processing of our substrate was needed. We therefore tried to establish a transient-expression system in cells of phylogenetically distant species. We chose a Sindbis virus-based system because of the broad host range of this alphavirus (39, 44). Briefly, a tag sequence coding for the LexA BD domain (BD) and a cDNA fragment from the BVDV JaCP sequence coding for the LC3 insertion together with the amino-terminal part of the NS3 protein were cloned into the Sindbis virus expression vector pSinRep5, resulting in construct pSin-LC3. As a control, construct pSin-LC3Δ, which is equivalent to pSin-LC3 but which contains a deletion of the 3′ terminal 18 codons of the LC3-coding sequence, was established. This deletion was shown before to inhibit LC3-dependent processing (not shown). After cotransfection of BHK-21 cells with RNA derived from one of the two constructs and the DH-EB helper plasmid (6) a stock of infectious Sindbis virus particles was established for each construct and used for infection of different cell lines. In addition to a BHK-21 control, avian (chicken embryonic fibroblasts, HFB-R cells), fish (rainbow trout, RTG cells), and insect cells (mosquito [Aedes albopictus], C6/36 cells) were infected with the recombinant virus. Protein extracts were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an antiserum directed against the LexA BD protein, which detects the uncleaved substrate and the amino-terminal processing product. In all four tested systems, pSin-LC3 yielded both the full-length product and a band with the size of the processed form of the expressed protein substrate (Fig. 2). The processing was dependent on the presence of the full-length LC3 sequence since pSin-LC3Δ was not cleaved (Fig. 2). As the processing leads to products that comigrate in the gel and is dependent on the integrity of the LC3 sequence, it can be concluded that the cleavage was conducted in each cell line by a functionally homologous protease and occurred most likely at the same position of the protein.

FIG. 2.

Processing of a bovine LC3 fusion protein in cells of different origins. Shown is the expression of proteins containing LC3 sequences in cells of different origins. A Sindbis virus expression system was used to express a substrate composed of the LexA BD domain, the LC3 insertion as found in the BVDV isolate JaCP, and a fragment of the JaCP NS3 protein (plasmid, pSin-LC3; protein, BD/LC3/NS3) or the same protein with a deletion of the carboxy-terminal 18 amino acids of the LC3 insertion (plasmid, pSin-LC3Δ; protein, BD/LC3Δ/NS3). Protein extracts of infected cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with a commercially available antiserum against the LexA-BD protein. The positions of molecular mass markers in kilodaltons are on the left. Arrows, indicated proteins.

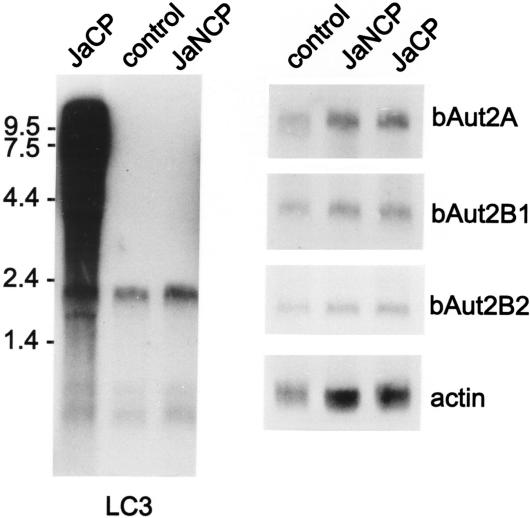

Coexpression of candidate proteases and viral fusion protein in yeast.

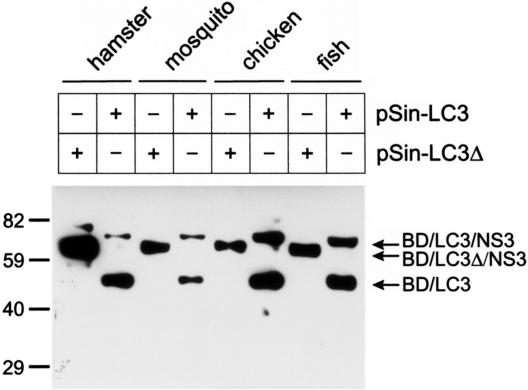

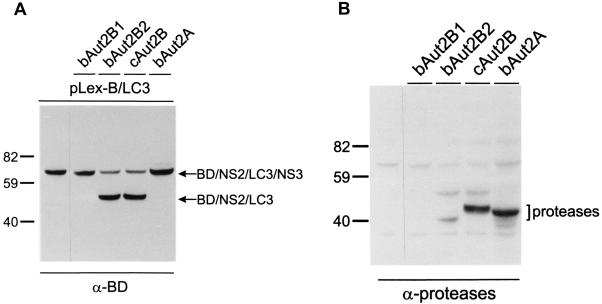

Expression in yeast was done to investigate whether our candidate proteases were able to cleave a mammalian substrate containing LC3. For this purpose an expression construct was established in plasmid pLexA. The substrate construct expressed a fusion protein composed of a BD tag, a fragment of the BVDV JaCP NS2, the LC3 insertion of BVDV JaCP, and a fragment of the viral NS3 protein (BD/NS2/LC3/NS3; plasmid pLex-B/LC3). For expression of the putative proteases, the above-described pYES2 plasmids were used. Analysis of protein extracts prepared from yeast aut2Δ mutants carrying the plasmid pLex-B/LC3 revealed only the unprocessed form of the target protein (Fig. 3A). The recombinant yeast clones carrying one of the protease constructs in addition to plasmid pLex-B/LC3 showed different phenotypes. Efficient processing of the mammalian protein was observed for the clones carrying the plasmids coding for cAut2B and bAut2B2 but not bAut2B1 or bAut2A (Fig. 3A). However, the last protease could apparently cleave the product with very low efficiency since a weak band corresponding to the size of the processing product was detectable after long exposure (not shown). To verify that the absence (bAut2B1) or the very low efficiency of processing (bAut2A) was not due to a defect in expression of the putative proteases, the same blot was also analyzed with antisera directed against the respective gene products. These sera had been raised against peptides specific for either protease bAut2A or bAut2B. Proteases cAut2B, bAut2B2, and bAut2A were readily detected, whereas bAut2B1 was not visible (Fig. 3B). Thus, the defect with regard to substrate processing in cells expressing bAut2B1 could be due to the absence of (sufficient amounts of) the protease. The bAut2B1 protein might be unstable or might not be expressed due to an unknown problem in protein expression.

FIG. 3.

Coexpression of candidate proteases and LC3 substrate in yeast. Shown is coexpression of a mammalian substrate protein containing LC3 with different candidate proteases. Plasmid pLex-B/LC3 (codes for protein BD/NS2/LC3/NS3) was expressed in aut2Δ yeast cells (strain YCV3) either with the pYES2 plasmid alone (left lane) or with pYES2 plasmids coding for one of the bovine candidate proteases (bAut2A, bAut2B1, or bAut2B2) or the chicken protease (cAut2B). The protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The same blot was first analyzed with the antiserum against LexA-BD (α-BD; A) and then with a mixture of antisera directed against conserved regions within the A and B proteases (α-proteases; B). Note that in panel B the bands already detected in panel A are still visible. For unknown reasons the expression level of bAut2B2 seemed to be lower than that of bAut2A or cAut2B.

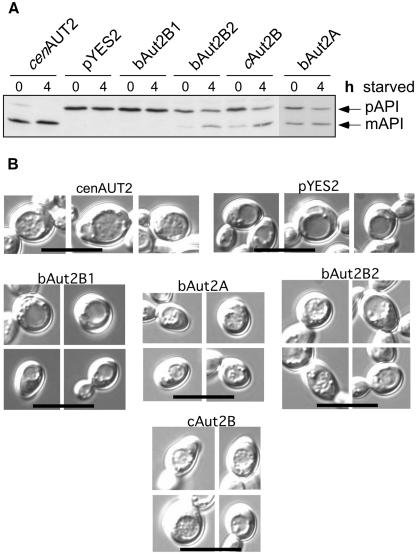

It was shown recently that two Drosophila homologues of Aut2/Apg4 are able to complement an Aut2/Apg4 defect in yeast. Both autophagy and maturation of pAPI were rescued by the insect proteins (47). It was therefore interesting to investigate whether the mammalian and avian homologues can also be used to rescue the yeast mutant. As shown in Fig. 4A, Aut2/Apg4-deficient mutants carrying plasmids coding for cAut2B, bAut2B2, and bAut2A but not bAut2B1 show conversion of pAPI to mature API (mAPI), in contrast to results for the original mutant. However, pAPI maturation was incomplete compared to the result observed in wild-type yeast. Nevertheless, the activity of the three higher-eukaryote proteases for inducing API maturation was sufficient to allow the rescue of the defect in accumulation of autophagic bodies in the vacuoles of the mutant yeast cells (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the observed complementation of the pAPI maturation defect, fewer autophagic bodies accumulated than accumulated in cells expressing the yeast Aut2p.

FIG. 4.

Rescue of yeast Aut2/Apg4 mutants by higher mammalian and avian proteases. Autophagy is impaired in yeast cells with inactivated protease Aut2p/Apg4p, as detectable in, e.g., a defect in maturation of pAPI and the inability to accumulate autophagic bodies in the vacuole during starvation. The different candidate proteases homologous to Aut2p/Apg4 were expressed in aut2-deficient yeast cells and tested with regard to trans complementation of the defects concerning pAPI maturation (A) and accumulation of autophagic bodies in the vacuole (B). (A) aut2Δ yeast cells expressing, from left to right, the yeast AUT2 gene, an empty pYES2 vector, and the indicated candidate mammalian proteinases. The cells were grown in selective galactose medium to the stationary phase (0 h starved) and further incubated in 1% potassium acetate for 4 h (4 h starved). Crude cell extracts were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, electroblotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with antibodies against pAPI. mAPI, mature API. (B) aut2Δ yeast cells expressing the candidate mammalian proteinases from a pYES2 vector were checked for their ability to accumulate autophagic bodies in their vacuoles when starved for nitrogen in the presence of the proteinase B inhibitor PMSF. The cells were grown in selective galactose medium to the stationary phase and further starved for 4 h in nitrogen-free SD(-N) medium containing 1 mM PMSF. As controls cells expressing the yeast AUT2 and cells carrying an empty pYES2 vector are included. The cells were visualized by light microscopy with Nomarski optics. Bar: 10 μm. The vacuole is easily seen as a round structure in the center of the cell. Autophagic bodies look like granules within the vacuole.

Taken together these results indicate that bAut2B2 represents the protease responsible for processing mammalian LC3. Interestingly, bAut2A is not able to process LC3 efficiently but can substitute for Aut2p/Apg4p in yeast and thus has to be able to cleave the yeast LC3 homologue Aut7p/Apg8p correctly.

Analyses based on in vitro translation.

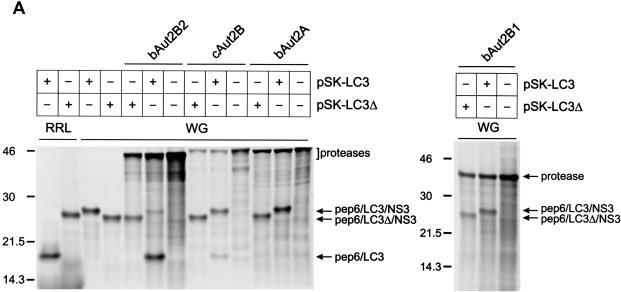

Processing of the NS2/LC3/NS3 fragment encoded by a carboxy-terminally truncated pEx7/JaCP had also been observed after translation of the respective RNA in RRL (pEx7/JaCPΔ) (29). Translation of such a substrate in WG offered an easy opportunity to test whether the plant system also provided an activity able to process mammalian LC3. As a substrate, a plasmid that codes for the amino-terminal pep6 tag, the LC3 insertion found in BVDV JaCP, and part of BVDV NS3 (pSK-LC3) was established. After translation of an RNA derived from pSK-LC3 in WG, cleavage could not be detected, whereas a control reaction with RRL yielded the cleaved products (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 1, respectively). Cotranslation in WG of the substrate and the different proteases resulted in detection of efficient cleavage for bAut2B2. Also cAut2B was able to process the substrate but with somewhat lower efficiency. In contrast, processing could not be observed for bAut2B1 and bAut2A. Once again, a second substrate construct with a deletion encompassing the 3′-terminal 18 codons of the LC3-coding sequence was established to serve as a control (pSK-LC3Δ). As expected, the respective translation product was not processed in any of the translation or cotranslation reactions. Taken together, the experiments show that WG does not contain an LC3-specific protease compatible with the mammalian substrate but can serve as a test system in cotranslation experiments. Once again, processing of the LC3 substrate was observed for bAut2B2 and cAut2B but not for bAut2A and bAut2B1. Thus, the results are equivalent to those of the coexpression studies in yeast, but, in contrast to the experiments conducted with yeast, bAut2B1 was clearly detected after translation in WG, so the negative result cannot be due to the absence of (sufficient amounts of) the protease.

FIG. 5.

In vitro translation of LC3 substrates and proteases in WG. Shown is coexpression of mammalian substrates and candidate proteases by in vitro translation. Fusion proteins composed of part of BVDV NS2 (pep6) and LC3-derived sequences with different carboxy-terminal extensions were expressed by in vitro translation using either the RRL or the WG system as indicated. (A) The LC3 sequence was either the authentic insertion identified in the BVDV JaCP polyprotein followed by part of BVDV NS3 (plasmid, pSK-LC3; protein, pep6/LC3/NS3) or an equivalent protein with the last 18 amino acids of LC3 deleted (plasmid, pSK-LC3Δ; protein, pep6/LC3Δ18/NS3). (B) The full-length bovine LC3 sequence, including the natural carboxy-terminal extension of five amino acids, followed by two tag sequences (VP5-six-His; plasmid pSK-cLC3) was expressed. The substrate was cotranslated with the different indicated proteases.

To test whether not only the viral fusion protein but also authentic cellular LC3 was processed by one of the proteases, a further substrate (pSK-cLC3) was established, which contained the complete cellular LC3-coding sequence, including the 3′ terminal extension of five codons, flanked by sequences coding for small tags. Cotranslation experiments with this substrate and the different proteases gave basically the same results found before with the substrate containing the viral sequences. Only bAut2B2 and cAut2B showed efficient processing of the substrate (Fig. 5B).

Interplay between virus and cell via LC3 and its protease.

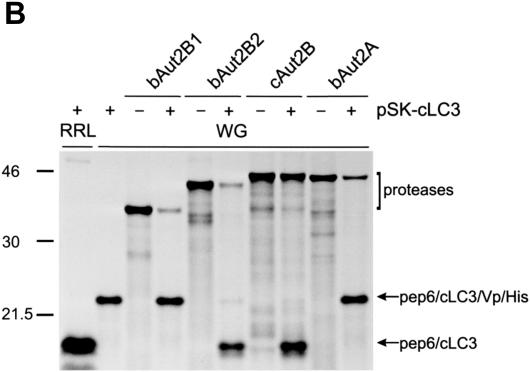

Evidence that viruses and cells interact at many different levels is accumulating. It was therefore interesting to investigate whether BVDV infection influences cellular expression of LC3 or bAut2B2. MDBK cells were infected with either BVDV JaCP or BVDV JaNCP. RNA of the infected cells and noninfected control cells was isolated 48 h postinfection and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and Northern blotting. Bovine cDNA probes corresponding to the mRNAs coding for LC3, bAut2A, bAut2B1, or bAut2B2 were used for the hybridization. A chicken β-actin sequence served as a control. As can be seen in Fig. 6, all three proteases are expressed in the MDBK cells. We found no indication of significant changes with regard to the expression levels of either the protease or the LC3 mRNAs upon virus infection (among the four types of RNAs, variation of signal strength was less than 20% when several independent experiments were taken together).

FIG. 6.

Northern blot with an LC3 probe and different protease probes. RNA of MDBK cells (control) and MDBK cells infected with the indicated viruses was analyzed in a Northern blot with an LC3 probe (left) or probes specific for the different (putative) protease genes identified in this report. A chicken actin probe served as a control. The probes used for hybridization are indicated below or on the right of the gels. On the left, size marker bands for the left gel are indicated. For MDBK cells, hybridization with an LC3 probe leads to bands of about 2.0, 0.65, and 0.5 kb. Because of the smear resulting from the partially degraded viral RNA, the LC3 cellular signal could not be quantified for JaCP-infected cells.

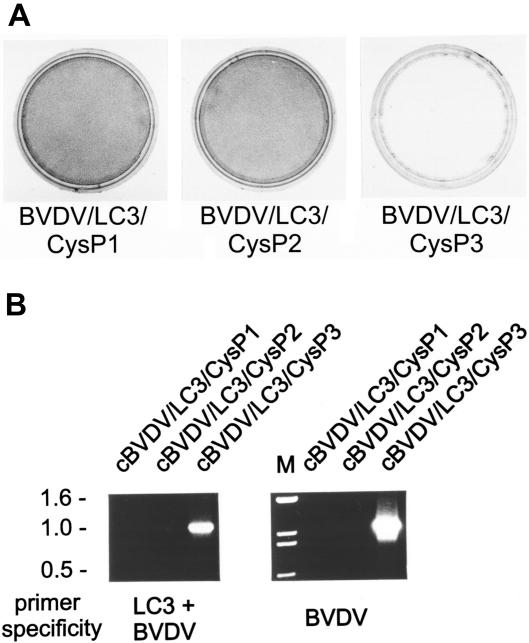

To see whether the proteolytic processing at the LC3/NS3 site in the polyprotein of a virus with an LC3 insertion is important for virus replication, we established full-length viral cDNA clones with LC3-coding insertions that contain mutations in the cellular sequence close to its 3′ border. We selected mutations affecting position P1 or P2 of the LC3/NS3 cleavage site, for which in separate investigations a considerable reduction of the processing activity had been observed. Changes of G to C at the P1 position and of F to C at the P2 position were selected for the experiments. The mutations reduce the cleavage efficiency to less than 20% of the wild-type level (our unpublished data). A mutant with C instead of T at position P3 was included in the experiments, because this change reduced cleavage efficiency to only 94% of the wild-type level. We had already shown before that a viral RNA containing the LC3 insertion but no duplication of the NS3-coding sequence is not able to promote the generation of infectious progeny virus unless it is introduced into a cell harboring a noncp BVDV helper virus. We tested the full-length RNAs with the mutations after transfection of both infected and noninfected MDBK cells. The RNA with the wild-type LC3 insertion served as a control. None of the RNAs was able to induce the generation of virus upon transfection into noninfected cells (data not shown). As already published before, cell lysis was observed when MDBK cells infected with a noncp BVDV helper virus were transfected with the RNA containing the wild-type LC3 insertion (29). We were also able to detect CPE after transfection of cells with the P3 mutant RNA. In contrast, no CPE was detectable in cells transfected with the other two mutant RNAs (Fig. 7A), indicating that the sequence changes reducing the cleavage at the LC3/NS3 site significantly impaired viral replication. RT-PCR with a primer pair specific for the RNAs containing the LC3 sequence yielded a fragment only for RNA of cells transfected with the P3 mutant (Fig. 7B). To exclude the possibility that the transfected RNA replicated but had lost (part of) the LC3 insertion, RT-PCR was conducted with a primer pair specific for the BVDV backbone of the infectious clone, but once again an amplicon was observed only for the P3 mutant (Fig. 7B). Since no viral RNA was detected for the former mutant RNAs after five blind passages, it can be concluded that these RNAs did not replicate to considerable levels. For control purposes the mutant full-length clones were all converted to a wild-type noncp sequence and were subsequently shown to yield infectious virus without helper virus. The exchanged fragments were checked by nucleotide sequencing (not shown).

FIG. 7.

Transfection of full-length BVDV RNA with mutated LC3 insertion. MDBK cells infected with a noncp helper virus (BVDV NCP1 [31]) were transfected with RNA transcribed in vitro from BVDV full-length plasmids (30) with mutated LC3 insertions and no duplication of viral sequences. As indicated, the mutations affected the LC3 sequence upstream of the LC3/NS3 cleavage site at position P1, P2, or P3. (A) Crystal violet staining of cells infected with cell lysate prepared after RNA transfection and three blind passages. (B) Agarose gel with samples obtained by RT-PCR with primers Ol-JasInsII and Ol-BVD30RII (specific for the combination of LC3 and BVDV NS3 coding sequences) (left) or Ol-BVD21.1 and Ol-BVD30RII (specific for a BVDV NCP7/CP7 NS2-3 fragment). Note that the primers do not amplify the sequences of the helper virus BVDV NCP1 used for infection of the cells prior to RNA transfection.

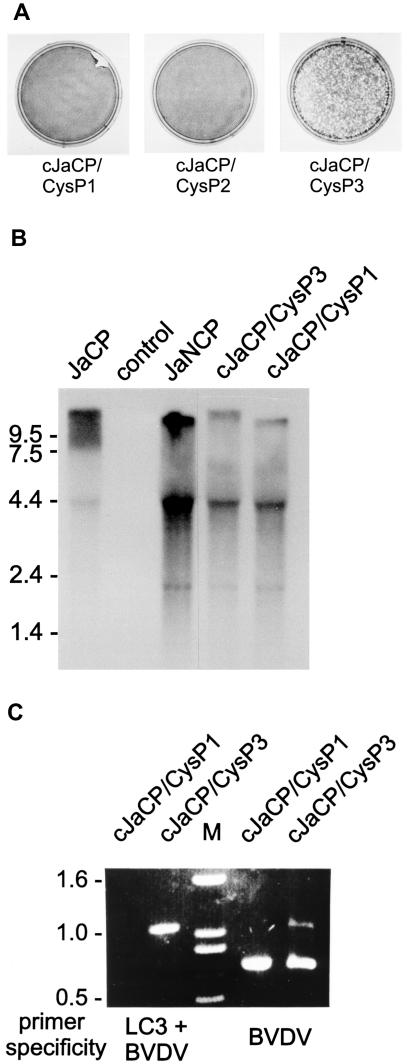

As published before full-length cDNA clones mimicking the genome organization of BVDV isolate JaCP with two duplications of viral sequences flanking the LC3 insertion yield autonomously replicating cp viruses (29). We inserted the LC3 insertions with the cysteine mutation at the P1, P2, or P3 position into such a construct resulting in full-length clones cJaCP/CysP1, cJaCP/CysP2, and cJaCP/CysP3, respectively. Recovery of infectious cp virus upon RNA transfection was routinely observed for the CysP3 construct (Fig. 8A). The other two constructs did not yield infectious virus except for one single case where transfection of RNA derived from a cJaCP/CysP1 plasmid resulted in recovery of a noncp virus. RNA analysis revealed that this virus had lost the duplication including the LC3 insertion by recombination since its genome comigrated with the JaNCP RNA and since RT-PCR with an LC3/BVDV-specific primer pair did not amplify a specific fragment (Fig. 8B and C). In control experiments we restored the wild-type configuration for all nonfunctional constructs and were then able to recover infectious viruses in all cases.

FIG. 8.

Transfection of full-length BVDV RNA containing duplicated viral sequences and mutated LC3 insertions. MDBK cells were transfected with RNA transcribed in vitro from plasmid pA/B-JaCP/dp (29) with mutated LC3 insertions. The parental plasmid mimics the BVDV JaCP genome with two duplications of viral sequences flanking the LC3 insertion. It was shown before that such an arrangement leads to a viable cp virus when the wild-type LC3 insertion is present (29). As indicated the mutations affected the LC3 sequence upstream of the LC3/NS3 cleavage site at position P1, P2, or P3. (A) Crystal violet staining of transfected cells (conducted about 72 h posttransfection). (B) Northern blot with a BVDV NCP1 probe (31) and RNAs of cells infected with the viruses cJaCP/CysP3 or cJaCP/CysP1 recovered from the above-described plasmids or the BVDV isolate JaCP or JaNCP. The “bands” visible in addition to the viral genome represent gel artifacts due to compression by the cellular 28S and 18S rRNAs. (C) Agarose gel with samples obtained by RT-PCR with primers Ol-JasInsII and Ol-BVD30RII (specific for the combination of LC3 and BVDV NS3 coding sequences) (left) or Ol-BVD21.1 and Ol-BVD30 RII (specific for a BVDV NCP7/CP7 NS2-3 fragment). The bands of about 0.7 kb in the right part correspond to an NS2-3 fragment without the LC3 insertion that is present in the 5′ terminal half of a genome with duplicated viral sequences in addition to the second copy of the gene that contains the LC3 insertion. For cJaCP/CysP1 the amplicon is derived from the noncp genome that was generated by deletion of the duplicated sequence including the LC3 insertion.

DISCUSSION

The coexistence of closely related cp and noncp viruses represents one interesting feature of pestiviruses. A variety of cp-BVDV-specific genome alterations is responsible for the lysis of the infected cells. All these genome alterations are somehow connected with the expression of the viral nonstructural protein NS3, in most cases by induction of proteolytic processing at the amino terminus of NS3. Among the mutations leading to a cp phenotype the integration of different cellular sequences is of special interest since the presence of these sequences in the viral genome sheds light on specific aspects of the biology of their cellular counterparts, namely, their involvement in proteolytic processing. LC3, the cellular sequence identified in BVDV JaCP, was first discovered as a 16.4-kDa protein in preparations of MAPs, including MAP1 and MAP2 (26). It was recently found that LC3 had, besides other mostly not well understood functions (23, 47, 51), a role in autophagy and possibly other processes involving membrane trafficking (17, 22, 23, 24). LC3 and its yeast homologue Aut7p/Apg8 might help during the initiation of vesicle formation, vesicle elongation, vesicle transport, and/or membrane fusion.

First indications for the importance of LC3 in autophagy were obtained for the homologous yeast protein Aut7p/Apg8p. Part of the mutations that blocked autophagy in yeast affected Aut7/Apg8, and it was soon discovered that the protein encoded by this gene was associated with the membranes of autophagic vesicles that are known as autophagosomes. After we had provided evidence for the fact that LC3 inserted in the polyprotein of a naturally occurring mutant BVDV served as a proteolytic processing signal, Kirisako and coworkers (19) found that Aut7p/Apg8p is processed at an equivalent position close to the carboxy terminus of the primary translation product. This process represents the first step in an activation cascade that finally leads to conjugation of the protein to phosphatidylethanolamine and integration of the conjugate in the membranes of autophagosomes (16). Processing of the Aut7p/Apg8p carboxy terminus is executed by the cysteine protease Aut2p/Apg4p and represents a crucial step in autophagy since Aut2/Apg4-deficient yeast mutants are defective in this process.

Based on sequence comparison studies two different homologues of Aut2 were identified in the human genome (HsApg4A and HsApg4B) (19). We demonstrate here for the first time that bovine cells contain mRNAs that code for proteins showing a high degree of similarity with the two human sequences. In addition, a sequence coding for a protein similar to HsApg4B was also identified in chicken cells. Only bAut2B2 and cAut2B were able to process a substrate protein in an LC3-dependent manner. It therefore can be concluded that these proteases represent the enzymes responsible for LC3 carboxy-terminal processing. Similar data have recently been published for the mouse, where a protease homologous to bAut2B2 was identified by a biochemical approach as the protease that cleaves mouse LC3 (15).

Our experiments aiming at identification of a system that allowed functional tests with the candidate proteases revealed the extreme conservation of the LC3-processing system since our mammalian substrate was processed by an intrinsic protease(s) in phylogenetically very distant avian, fish, and mosquito cells. Both the conserved size of the cleavage products and the requirement of the LC3 carboxy-terminal sequence suggest that the cleavage occurs in all cases at the same site downstream of the motif TFG, which was identified first as a cleavage site in our viral substrate and later in the yeast system. We also found indications for processing of the mammalian substrate in wild-type yeast, but the respective results could not be reproduced consistently. In any case, the rescue of a yeast AUT2 deletion mutant by two of the mammalian proteases and the chicken protease cAut2B proves the functional complementation of the processing system. The rescue of the yeast aut2/apg4 mutant was also possible with two different sequences from Drosophila melanogaster (47). This high degree of flexibility with regard to cross complementation is somewhat surprising since the different protease sequences are quite divergent. The obvious similarity of the substrates, especially at the cleavage site, together with a putatively conserved basic structure of the proteins is apparently sufficient to allow enzyme/substrate recognition and cleavage.

A still open question is why more than one Aut2p/Apg4p homologue is expressed in mammalian and insect cells. It is expected that the different proteases have clearly distinct functions. The deficiency of bAut2B1 for processing LC3 in all tested systems and its inability to complement the defect in aut2/apg4-deficient yeast cells indicate that this protein represents no active protease or processes a substrate different from LC3. The latter conclusion is even more likely for bAut2A. It has to be considered in this context that mammalian cells contain at least two LC3-homologous proteins, namely, the Golgi-associated ATPase Enhancer of 16 kDa (GATE-16) (41) and γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) (49). GATE-16 was first described as a membrane transport modulator in the constitutive secretory pathway (24, 41). It is localized in the Golgi apparatus, interacts with different proteins engaged in vesicle transport, and might assist in vesicle-membrane fusion. Interestingly, Aut7p/Apg8p seems to be the functional homologue of GATE-16 in yeast and can replace GATE-16 in assays mimicking mammalian intra-Golgi transport in vitro (23). In contrast, it was proposed that GABARAP plays a role in receptor anchoring and clustering via its ability to interact with the microtubule and microfilaments (49). Both proteins have considerable sequence similarity with LC3, including glycine 120. It was shown that these two proteins are also processed at their carboxy termini (45), and sequences coding for fragments of both proteins have recently been identified in the genomes of cp pestiviruses (5). HsApg4A expressed in bacteria was shown to cleave GATE-16, so future experiments might show that this protease is responsible for processing this protein in vivo (43).

It is likely that the system of mammalian homologues of Aut7p/Apg8p and Aut2p/Apg4p is even more complex than would be expected on the basis of the above-described data. A recent publication reported that human and mouse cells contain sequences able to encode two additional homologues of Aut2p/Apg4p. One of these new sequences was able to complement an Aut2/Apg4 defect in yeast (27). Taken together, it seems that in higher-eukaryote cells the yeast Aut7p/Apg8p system has been differentiated so that at least three Aut7p/Apg8 homologues with different functions exist. Each of these proteins might be processed by its own specific protease. Moreover, the existence of multiple Aut2p/Apg4p-homologous proteases in higher eukaryotes could also be necessary for differentiation with regard to deconjugation of the Aut7p/Apg8p homologues attached to their different targets. It is an interesting result in this context that bAut2A, although not able to process LC3, can substitute for Aut2p/Apg4p, so that the systems seem to be more interchangeable between yeast and bovine cells than between the different substrates within one species. Further analyses are necessary to verify whether the existence of more than one Aut2p/Apg4p-homologous protease is indeed a consequence of this differentiation with, e.g., each protease responsible for activation cleavage of one individual Aut7p/Apg8p homologue in vivo. It is also possible, however, that these proteases have totally different functions since it has been reported recently that four different mouse homologues of Aut7p/Apg8p, including LC3, GATE-16, and GABARAP, are all cleaved by a single protease homologous to Aut7p/Apg8p (15).

Viruses are known to interact with their host cells at different levels, including regulation of gene expression. It therefore is possible that BVDV infection specifically influences the expression of sequences that serve as partners for RNA recombination or code for proteins important for the processing of a recombinant polyprotein from a cp BVDV. However, we show here that, at least with regard to LC3 and its corresponding protease, no significant changes of the expression levels can be detected. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that the virus by chance picked up a sequence that is not induced by viral replication. It is likely that neither LC3 nor its protease belongs to a set of cellular proteins recruited by the virus for its normal replication; instead, LC3 was probably specifically selected for its ability to serve as a processing signal in the context of virus cytopathogenicity.

The genome of BVDV JaCP contains a duplication of viral NS2-3/NS4-coding sequences flanking the LC3 insertion, and we have shown before that a viral genome containing LC3 but no duplication cannot direct the generation of infectious progeny virus but can be propagated in the presence of a helper virus (29). As shown here, mutations considerably reducing the processing at the LC3/NS3 site prevent recovery of the defective viruses even after several blind passages, so it can be concluded that replication of these RNAs is (nearly) blocked. It has to be stressed that the mutations tested here all are located within the LC3 sequence and therefore do not change a viral protein with a distinct function in viral replication. This stands in marked contrast to the data published before where mutations within the NS2 gene were tested (20). We therefore can conclude now that interference with the cp-BVDV-specific processing at the amino terminus of NS3 has a prominent effect on virus viability. This can either be due to an increase of the concentration of the aberrant fusion protein NS2/LC3/NS3 or can reflect a dependency of the virus on a certain level of processing, as proposed before (20). As shown in the experiments with the RNAs mimicking the JaCP genome, impairment of processing at the NS3 amino terminus cannot be overcome by a second copy of the NS3 gene in a genome containing a duplication. It was shown before that NS3 and most other nonstructural pestivirus proteins cannot be provided in trans to support viral RNA replication (11, 12). Obviously, the duplication and the cellular insertion lead to a “quasi-trans” arrangement of the functional copy of the gene located upstream of the insertion. Nevertheless, low-level RNA replication was apparently occurring for the CysP1 construct with duplication since the mutated viral genome was able to delete the defective processing signal together with the duplicated viral sequences by recombination. In any case, it has to be stated that a BVDV containing an LC3 coding sequence insertion in its genome is absolutely dependent on the cellular LC3-specific processing in order to replicate its RNA efficiently and generate infectious progeny virus.

The LC3-Aut7p/Apg8p system is reminiscent of the ubiquitin system. The fundamental processes of proteolytic processing at the carboxy terminus, activation, and conjugation are found in both systems (see references 35, 48, and 50 for recent reviews). Moreover, ubiquitin and LC3 seem to be multifunctional, with one function being to provide a kind of covalently bound label for cellular molecules or structures that marks the target for further processes. This functional similarity is also represented in the structure of the proteins since a ubiquitin-like fold was identified in the three-dimensional structure of the LC3 homologue GATE-16 (36). Apparently, the processes involving conjugation of small proteins after carboxy-terminal cleavage and activation are highly important for living cells, so that the processes themselves and the interacting components are among the most conserved systems of biology. Pestiviruses have learned to exploit these systems for their own purposes. Nearly all members of the respective families of cellular sequences can be found as insertions in cp pestivirus genomes. It seems to be worthwhile to keep an eye on new cp pestivirus isolates since they might have found further interesting candidate proteins with not yet known cellular functions.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Meanwhile, the nomenclature of autophagy genes has been unified (D. J. Klionsky, J. M. Cregg, W. A. Dunn, S. D. Emr, Y. Sakai, I. V. Sandoval, A. Sibirny, S. Subramani, M. Thumm, M. Veenhuis, and Y. Ohsumi, Dev. Cell 5:539-545, 2003). Accordingly, AUT7/APG8 is now termed ATG8, and AUT2/APG4 is now termed ATG4.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maren Ziegler, Janett Wieseler, Petra Wulle, and Uli Wulle for excellent technical assistance; Hubert Kalbacher (University of Tübingen, Germany) for his help concerning the design of the protease specific antisera; and Sondra Schlesinger for the Sindbis virus DH-EB helper plasmid. We are grateful to Walter Fuchs (BFAV, Insel Riems, Germany) for his help with the pLexA-based protein expression in yeast, to Peter Enzmann for his help with the fish cell culture, to Fabian Käsermann and Christoph Kempf for the AA cells, and to Roland Riebe (BFAV) for the HFB-R cells.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant DFG Me1367/2-3, 2-4, 2-5, 2-6) and the Fond der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, and D. D. Moore (ed.). 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Baroth, M., M. Orlich, H. J. Thiel, and P. Becher. 2000. Insertion of cellular NEDD8 coding sequences in a pestivirus. Virology 278:456-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth, H., and M. Thumm. 2001. A genomic screen identifies AUT8 as a novel gene essential for autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 274:151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becher, P., A. D. Shannon, N. Tautz, and H.-J. Thiel. 1994. Molecular characterization of border disease virus, a pestivirus from sheep. Virology 198:542-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becher, P., H. J. Thiel, M. Collins, J. Brownlie, and M. Orlich. 2002. Cellular sequences in pestivirus genomes encoding gamma-aminobutyric acid (A) receptor-associated protein and Golgi-associated ATPase enhancer of 16 kilodaltons. J. Virol. 76:13069-13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bredenbeek, P. J., I. Frolov, C. M. Rice, and S. Schlesinger. 1993. Sindbis virus expression vectors: packaging of RNA replicons by using defective helper RNAs. J. Virol. 67:6439-6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. A. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fricke, J., M. Gunn, and G. Meyers. 2001. A family of closely related bovine viral diarrhea virus recombinants identified in an animal suffering from mucosal disease: new insights into the development of a lethal disease in cattle. Virology 291:77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuta, S., K. Miura, T. Copeland, W. H. Shang, A. Oshima, and T. Kamata. 2002. Light chain 3 associates with a Sos1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor: its significance in the Sos1-mediated Rac1 signaling leading to membrane ruffling. Oncogene 21:7060-7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant, G. A. 1998. Synthetic peptides for production of antibodies that recognize intact proteins, p. 11.16.1-11.16.10. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Grassmann, C. W., O. Isken, and S. E. Behrens. 1999. Assignment of the multifunctional NS3 protein of bovine viral diarrhea virus during RNA replication: an in vivo and in vitro study. J. Virol. 73:9196-9205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grassmann, C. W., O. Isken, N. Tautz, and S. E. Behrens. 2001. Genetic analysis of the pestivirus nonstructural coding region: defects in the NS5A unit can be complemented in trans. J. Virol. 75:7791-7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guldener, U., S. Heck, T. Fielder, J. Beinhauer, and J. H. Hegemann. 1996. A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2519-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinz, F. X., M. S. Collett, R. H. Purcell, E. A. Gould, C. R. Howard, M. Houghton, J. M. Moormann, C. M. Rice, and H.-J. Thiel. 2000. Family Flaviviridae, p. 859-878. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 15.Hemelaar, J., V. S. Lelyveld, B. M. Kessler, and H. L. Ploegh. 2003. A single protease, Apg4B, is specific for the autophagy-related ubiquitin-like proteins GATE-16, MAP1-LC3, GABARAP, and Apg8L. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51841-51850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ichimura, Y., T. Kirisako, T. Takao, Y. Satomi, Y. Shimonishi, N. Ishihara, N. Mizushima, I. Tanida, E. Kominami, M. Ohsumi, T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 2000. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature 408:488-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabeya, Y., N. Mizushima, T. Ueno, A. Yamamoto, T. Kirisako, T. Noda, E. Kominami, Y. Ohsumi, and T. Yoshimori. 2000. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19:5720-5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirisako, T., M. Baba, N. Ishihara, K. Miyazawa, M. Ohsumi, T. Yoshimori, T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 1999. Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 147:435-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirisako, T., Y. Ichimura, H. Okada, Y. Kabeya, N. Mizushima, T. Yoshimori, M. Ohsumi, T. Takao, T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 2000. The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J. Cell Biol. 151:263-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kümmerer, B. M., and G. Meyers. 2000. Correlation between point mutations in NS2 and the viability and cytopathogenicity of bovine viral diarrhea virus strain Oregon analyzed with an infectious cDNA clone. J. Virol. 74:390-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kümmerer, B. M., N. Tautz, P. Becher, H. Thiel, and G. Meyers. 2000. The genetic basis for cytopathogenicity of pestiviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 77:117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang, T., E. Schaeffeler, D. Bernreuther, M. Bredschneider, D. H. Wolf, and M. Thumm. 1998. Aut2p and Aut7p, two novel microtubule-associated proteins, are essential for delivery of autophagic vesicles to the vacuole. EMBO J. 17:3597-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Legesse-Miller, A., Y. Sagiv, R. Glozman, and Z. Elazar. 2000. Aut7p, a soluble autophagic factor, participates in multiple membrane trafficking processes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32966-32973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legesse-Miller, A., Y. Sagiv, A. Porat, and Z. Elazar. 1998. Isolation and characterization of a novel low molecular weight protein involved in intra-Golgi traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3105-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindenbach, B. D., and C. M. Rice. 2001. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 991-1042. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, E. E. Griffin, R. A. lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann, S. S., and J. A. Hammarback. 1994. Molecular characterization of light chain 3. A microtubule binding subunit of MAP1A and MAP1B. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11492-11497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marino, G., J. A. Uria, X. S. Puente, V. Quesada, J. Bordallo, and C. Lopez-Otin. 2003. Human autophagins, a family of cysteine proteinases potentially implicated in cell degradation by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3671-3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers, G., T. Rümenapf, and H.-J. Thiel. 1989. Ubiquitin in a togavirus. Nature 341:491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers, G., D. Stoll, and M. Gunn. 1998. Insertion of a sequence encoding light chain 3 of microtubule-associated proteins 1A and 1B in a pestivirus genome: connection with virus cytopathogenicity and induction of lethal disease in cattle. J. Virol. 72:4139-4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyers, G., N. Tautz, P. Becher, H.-J. Thiel, and B. Kümmerer. 1996. Recovery of cytopathogenic and noncytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhea viruses from cDNA constructs. J. Virol. 70:8606-8613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyers, G., N. Tautz, E. J. Dubovi, and H.-J. Thiel. 1991. Viral cytopathogenicity correlated with integration of ubiquitin-coding sequences. Virology 180:602-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyers, G., N. Tautz, and H.-J. Thiel. 1995. Host genes in viral genomes, p. 91-102. In A. J. Gibbs, C. H. Calisher, and F. Garcia-Arenal (ed.), Molecular basis of virus evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 33.Meyers, G., and H.-J. Thiel. 1995. Cytopathogenicity of classical swine fever virus caused by defective interfering particles. J. Virol. 69:3683-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyers, G., and H.-J. Thiel. 1996. Molecular characterization of pestiviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 47:53-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noda, T., K. Suzuki, and Y. Ohsumi. 2002. Yeast autophagosomes: de novo formation of a membrane structure. Trends Cell Biol. 12:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paz, Y., Z. Elazar, and D. Fass. 2000. Structure of GATE-16, membrane transport modulator and mammalian ortholog of autophagocytosis factor Aut7p. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25445-25450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi, F., J. F. Ridpath, and E. S. Berry. 1998. Insertion of a bovine SMT3B gene in NS4B and duplication of NS3 in a bovine viral diarrhea virus genome correlated with the cytopathogenicity of the virus. Virus Res. 57:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu, L., L. K. McMullan, and C. M. Rice. 2001. Isolation and characterization of noncytopathic pestivirus mutants reveals a role for nonstructural protein NS4B in viral cytopathogenicity. J. Virol. 75:10651-10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice, C. M. 1996. Alphavirus-based expression systems. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 397:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinck, G., C. Birghan, T. Harada, G. Meyers, H. J. Thiel, and N. Tautz. 2001. A cellular J-domain protein modulates polyprotein processing and cytopathogenicity of a pestivirus. J. Virol. 75:9470-9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sagiv, Y., A. Legesse-Miller, A. Porat, and Z. Elazar. 2000. GATE-16, a membrane transport modulator, interacts with NSF and the Golgi v-SNARE GOS-28. EMBO J. 19:1494-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 43.Scherz-Shouval, R., Y. Sagiv, H. Shorer, and Z. Elazar. 2003. The C-terminus of GATE-16, an intra-Golgi transport modulator, is cleaved by the human cysteine protease HsApg4A. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14053-14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlesinger, S. 2001. Alphavirus vectors: development and potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 1:177-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanida, I., M. Komatsu, T. Ueno, and E. Kominami. 2003. GATE-16 and GABARAP are authentic modifiers mediated by Apg7 and Apg3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300:637-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiel, H.-J., P. G. W. Plagemann, and V. Moennig. 1996. Pestiviruses, p. 1059-1073. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 1. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thumm, M., and T. Kadowaki. 2001. The loss of Drosophila APG4/AUT2 function modifies the phenotypes of cut and Notch signaling pathway mutants. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:657-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varshavsky, A., G. Turner, F. Du, and Y. Xie. 2000. Felix Hoppe-Seyler Lecture 2000. The ubiquitin system and the N-end rule pathway. Biol. Chem. 381:779-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, H., and R. W. Olsen. 2000. Binding of the GABA(A) receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) to microtubules and microfilaments suggests involvement of the cytoskeleton in GABARAPGABA(A) receptor interaction. J. Neurochem. 75:644-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkinson, K. D. 1997. Regulation of ubiquitin-dependent processes by deubiquitinating enzymes. FASEB J. 11:1245-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou, B., and M. Rabinovitch. 1998. Microtubule involvement in translational regulation of fibronectin expression by light chain 3 of microtubule-associated protein 1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 83:481-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]