Abstract

Many people routinely criticise themselves. While self-criticism is largely unproblematic for most individuals, depressed patients exhibit excessive self-critical thinking, which leads to strong negative affects. We used functional magnetic resonance imaging in healthy subjects (N = 20) to investigate neural correlates and possible psychological moderators of self-critical processing. Stimuli consisted of individually selected adjectives of personally negative content and were contrasted with neutral and negative non-self-referential adjectives. We found that confrontation with self-critical material yielded neural activity in regions involved in emotions (anterior insula/hippocampus–amygdala formation) and in anterior and posterior cortical midline structures, which are associated with self-referential and autobiographical memory processing. Furthermore, contrasts revealed an extended network of bilateral frontal brain areas. We suggest that the co-activation of superior and inferior lateral frontal brain regions reflects the recruitment of a frontal top–down pathway, representing cognitive reappraisal strategies for dealing with evoked negative affects. In addition, activation of right superior frontal areas was positively associated with neuroticism and negatively associated with cognitive reappraisal. Although these findings may not be specific to negative stimuli, they support a role for clinically relevant personality traits in successful regulation of emotion during confrontation with self-critical material.

Keywords: self-criticism, self-discrepancies, functional magnetic resonance imaging, lateral frontal cortex

INTRODUCTION

Human beings routinely compare themselves to internalised standards and normally strive to minimise the gap between differing representations of the self; these gaps are known as self-discrepancies. Disagreement between how people see themselves and how they want to be seen by others may cause emotional and psychological derangement (Higgins, 1987) that may surface as harsh self-criticism. Self-criticism is a form of negative self-judgment and self-evaluation, and it may concern various aspects of the self, such as physical appearance, social behaviour, inner thoughts and emotions, personality characteristics and intellectual abilities (Gilbert and Miles, 2000). The potentially harmful impact of self-criticism on mental health and its central involvement in depressive pathology (Blatt, 1982; Carver, 1983) raise the question of how healthy people deal with perceived self-discrepancies without experiencing adverse consequences.

Although a number of recent studies investigated the neural network involved in self-referential processing of healthy participants (see Qin and Northoff, 2011 for an overview) and depressed patients (Grimm et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2009; Lemogne et al., 2012; Yoshimura et al., 2013), the neural correlates of harsh self-criticism are less understood. In a recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiment, Longe et al. (2010) confronted healthy participants with various scenarios focusing on personal setbacks, mistakes or failures. Compared with neutral scenarios, self-critical processing was associated with activity in the lateral frontal cortex and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), suggesting possible associations between self-critical thinking, error processing and behavioural inhibition (Longe et al., 2010). In this experiment, participants were instructed to imagine being either self-critical or self-reassuring in standardised situation scenarios. In our study, we fostered self-relevance and emotional responses by presenting individually tailored self-critical stimuli. The processing self-critical stimuli can be conceptualised as an instance of self-referential processing which has been associated with activity in the default mode network in several independent studies (see van Buuren et al., 2010 for an overview). Within this distributed network the activation of cortical midline structures (CMS) was reported most consistently (Kelley et al., 2002; Fossati et al., 2003; Northoff et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2009; Lemogne et al., 2011; Qin and Northoff, 2011; D'Argembeau et al., 2012). Whereas frontal regions of the CMS have been associated with self-focused cognitive processes of evaluation and reappraisal (Ochsner et al., 2004; Northoff et al., 2006; Schmitz, 2007; Etkin et al., 2011), posterior parts within the CMS, namely the precuneus and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), are thought to link self-referential stimuli to past experiences (Fink et al., 1996; Cavanna and Trimble, 2006; Northoff et al., 2006). In addition, activation of the anterior insula has consistently been reported during emotional self-referential tasks (Modinos et al., 2009; Qin and Northoff, 2011). Considering an association between insula activation and the internally generated recall of subjective feelings and the evaluation of distressing cognitions (Phan et al., 2002; Craig, 2009), we hypothesise that enhanced insula activity will be observed during confrontation with self-critical stimuli. Furthermore, early emotion theories have already highlighted the critical involvement of the hippocampus–amygdala formation in emotional experiencing (Papez, 1937; MacLean, 1949). The hippocampus and amygdala are heavily interconnected (Pitkänen et al., 2006), and their interaction might be particularly important for the encoding of emotional events related to the self (Packard and Cahill, 2001; Phelps, 2004; Buchanan, 2007).

Processing of self-critical stimuli might not only involve the detection and reflexive experiencing of emotional evocation but could also involve the subsequent regulation of effective responses that preserve emotional control. Being confronted with unobtainable self-standards that are perceived as self-discrepancies, some might recruit reappraisal strategies for protecting the self. The ACC and the superior and inferior lateral frontal regions are assumed to play a central role in the top–down regulation of negative emotions by inhibiting and controlling the activation in limbic regions (Aron et al., 2004; Ochsner et al., 2004; Lieberman et al., 2007; Shackman et al., 2009). This top–down pathway seems to be centrally involved in successful emotion regulation, and there is growing evidence that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) is dysfunctional in its response to negative self-referential material in clinically depressed patients (Siegle et al., 2007; Hooley et al., 2009; Lemogne et al., 2009). Correspondingly, Hooley et al. (2005, 2009, 2012) showed that remitted depressed patients failed to activate the dlPFC, predominantly in the right hemisphere, when they heard tape-recorded critical utterances by their own mothers.

Excessive self-critical thinking may represent a psychological vulnerability to depressive symptoms (Sherry et al., 2013). Thus, examining neural activity and the potential risk and protective factors of depression during the processing of self-criticism in healthy subjects may contribute to a better understanding of the interaction between self-criticism and psychopathology. There is growing evidence suggesting a key role for right frontal brain areas in the distorted top–down pathway of dealing with criticism in depressed patients (Hooley et al., 2012), but the influence of potential psychological moderators is unclear. Therefore, we investigated the association between activity in the right superior frontal areas during confrontation with self-critical stimuli and self-reported levels of depressive symptomatology, neuroticism, self-judgment and cognitive reappraisal. Mildly depressed mood, neuroticism and self-judgment have been suggested as vulnerability factors of depressive states (Teasdale and Dent, 1987; Neff, 2003). Cognitive emotion regulation skills, on the other hand, serve as protective factors and are linked to lateral frontal brain areas (Ochsner and Gross, 2008). Furthermore, recent studies with healthy subjects have reported a positive association between dlPFC activation, self-reported levels of self-criticism (Longe et al., 2010) and perceived criticism by others (Hooley et al., 2012). These results might reflect enhanced frontal control.

The main goal of this study was to further understand the neural basis of processing self-critical material. Differences in neural activity related to self-critical vs neutral stimuli (contrast 1) may also be attributed to differences in other properties of the stimuli such as human vs non-human, or negative/emotional vs neutral contents. To control for these potential factors we also contrasted self-critical stimuli with negative stimuli that do not have an individual self-referential meaning (contrast 2). This negative non-self-referential category contains stimuli that are negative and potentially self-referential (e.g. dishonest, stupid, unattractive) but were previously marked by the individual as not relevant for the self-concept. Furthermore, we tried to intensify emotional reactions via the use of individualised self-critical stimuli, and we assessed the neural correlates of dealing with perceived self-discrepancies. As we confronted participants with personally unpleasant stimuli, we expected to observe enhanced activity in regions associated with self-related emotional responses, namely the anterior insula and the hippocampus–amygdala formation. We also expected the anterior and posterior CMS, which are related to self-referential and autobiographical processing, to have elevated activity levels following stimulation (Northoff et al., 2006). We further hypothesised that the lateral frontal cortex regions and the ACC would be recruited in an attempt to moderate potential limbic responses to self-threatening material. Based on the available literature about the connections between psychological factors and neural activity described before, we hypothesised that during the processing of self-critical material subjects displaying high levels of depressive symptomatology, neuroticism, and/or self-judgment would exhibit more activity in their right superior frontal areas, whereas subjects displaying high levels of cognitive reappraisal would have reduced activity in these same areas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We recruited 20 healthy, right-handed adults (15 women and 5 men with a mean age of 30 years, s.d.: 10.2 years). The participants had no history of neurological or psychiatric illness and no history of drug or alcohol abuse. All participants were native German speakers. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee, and all subjects gave written informed consent. Subjects’ vision was normal or corrected to near normal using contact lenses. Subjects were reimbursed for their participation and time.

Stimuli

We used 24 neutral adjectives and 48 individually selected negative adjectives (24 with individual self-reference and 24 without). All adjectives consisted of 1–3 syllables and ≤12 letters. Using a German Word Database (http://wortschatz.uni-leipzig.de), we determined that all adjectives reached a frequency level of ≤20, ensuring common use in the everyday language (frequency level based on Zipfs’ law, which states that the reference word the [der] is 220 times more frequent than the respective word). The 24 neutral stimuli (e.g. weekly, oval, cursive) were the same for all participants and were pre-selected by the authors from 100 potentially neutral words. Forty-two volunteers (21 women and 21 men) rated the valence of all adjectives using a scale ranging from −2 (very negative) to +2 (very positive). Twenty-four adjectives were selected based on the following criteria: modal value of 0, mean value between −0.20 and 0.20 and minimal standard error. The pre-selection of negative stimuli (e.g. fat, boring, jealous) was based on Anderson’s list of personality-trait words (Anderson, 1968) and on the German word database. To cover the main classes of personal characteristics in German (Angleitner et al., 1990), we included adjectives from the following five categories: dispositions (temperament and character traits), abilities and talents, temporary conditions, social and reputational aspects and appearance. Furthermore, we ensured via a web-based and anonymous survey that we did not disregard any important aspects. Volunteers (N = 41, 24 women and 17 men) freely produced adjectives describing negative aspects of themselves or others without restrictions. Taking into account database studies and the free production of adjectives, we chose 52 negative prototypes, which covered the most important personality domains. As a final step, each prototype was supplemented with three synonyms that matched the same objective criteria. We assumed that the synonyms likely activated the same specific self-schema as the prototypical adjective (Markus, 1977).

Before the fMRI assessment, each participant completed a set of questionnaires and a worksheet, allowing the participant to determine their individual set of self-critical adjectives at home. Subjects were instructed to mark all adjectives in the list of 52 prototypes that they experienced as unwanted self-discrepancies. Next, subjects were asked to select the six prototypes that fit themselves the most; they were also instructed to mark six prototypes that they evaluated as negative in other people but not in themselves. The six self-critical prototypes were rated in terms of their subjective strength of negative evaluation. The following question was asked: ‘how negative do you rate this characteristic of yourself?’, and responses were evaluated using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all negative to 5 = very negative. Non-self-referential prototypes were rated in terms of how negative the person judges the respective characteristic in others. The question ‘how negative do you rate the characteristic in other people?’ was evaluated using the same Likert scale. Based on each person’s worksheet, individually tailored experiments were implemented using the Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, http://www.neurobs.com). Stimuli were projected in the middle of a screen appearing on MRI-compatible goggles.

Experimental design

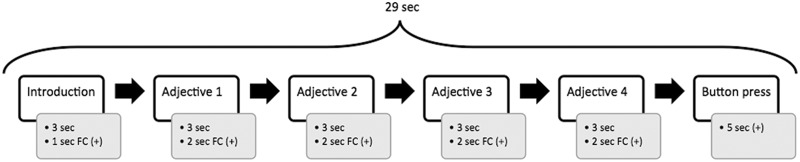

For each subject, we ran one session lasting ∼12 min; this session included 24 blocks each lasting ∼29 s (Figure 1). Four different types of blocks were presented in randomised order: six neutral blocks, six negative blocks with individualised self-critical adjectives, six blocks with individualised negative adjectives that were not self-critical and six blocks of rest. During the rest blocks, participants were instructed to relax and look at the fixation-cross for 29 s. A neutral block contained four of the 24 neutral adjectives presented in randomised order. Self-critical and negative blocks consisted of the six prototypes that were chosen by participants in advance, and these prototypes were interspersed with their three respective synonyms. Again, the order of presentation was completely randomised. During the experiment, each neutral or negative adjective was presented only once.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of one block including times of presentation (FC = fixation cross).

During the measurement, participants were instructed to read the adjectives silently and focus on the meaning of the adjectives as well as on their triggered emotional reactions. Each block started with an introduction (3 s) followed by a fixation cross (1 s). The introduction varied depending on the respective condition (neutral: ‘it is’ [‘oval’]; negative non-self-referential: ‘I am not’ [‘stupid’]; self-critical: ‘I am too’ [‘shy’]). Subsequently, the four adjectives relating to a particular self-schema were presented. Each adjective was projected for 3 s and followed by a fixation cross for 2 s. At the end of each block, participants were asked to press a specific button within a time period of 5 s. This task served as a low-level attention task and ensured that participants focused on the presented stimuli. As the response rate was 100% we did not have to exclude any subjects due to non-responses. Before the scan protocol was initiated, subjects participated in a practice run with meaningless words.

Image acquisition and data analysis

fMRI scanning was performed at the University Hospital of Psychiatry (Zurich, Switzerland) using a 3-T Philips Intera whole-body MR unit equipped with an eight-channel Philips SENSE head coil. Functional time series were acquired with a sensitivity-encoded (Pruessmann et al., 1999) singleshot echo-planar sequence (SENSE-sshEPI). Thirty-six contiguous axial slices were placed along the anterior–posterior commissure plane covering the entire brain. A total of 247 T2*-weighted echo planar image volumes with blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast (imaging parameters: repetition time = 3000 ms, echo time = 35 ms, 80 × 80 voxel matrix, interpolated to 128 × 128, voxel size = 2.75 × 2.75 × 4 mm3, SENSE acceleration factor R = 2.0) were acquired. The first four scans were discarded due to T1 saturation effects. For each participant, a T1-weighted high-resolution image was acquired.

For data analysis, we used the SPM8 parametric mapping software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk). Standard pre-processing steps included correction for slice timing, realignment to the first image, co-registration with the high-resolution T1-weighted image, normalisation into a standard stereotactic space (EPI template provided by the Montreal Neurological Institute, new voxel size = 2 × 2 × 2 mm3), and smoothing with an 8-mm full width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel. First-level analysis was performed on each subject in a fixed-effect model including the six movement regressors (realignment parameters) and the three condition regressors. The BOLD data were modelled with a block design convolved with the standardised canonical haemodynamic response function and its temporal derivative. Estimated beta-parameters and t-contrast images (containing weighted parameter estimates) were brought to the second-level random effect analysis. For the fMRI data group analysis, contrast images were analysed using one-sample t-tests with age and gender as covariates. Regarding the whole-brain analyses of contrast 1 (self-critical > neutral) and contrast 2 (self-critical > negative non-self-referential), statistical images were assessed at P = 0.001 uncorrected (single voxel level) and reported for family-wise error (FWE) correction at the cluster level (P = 0.05). As our a priori hypotheses regarding the insula and the hippocampus–amygdala formation were specific enough, we reported activations for these structures that survived an uncorrected threshold of P < 0.001 on a whole brain level and were significant at P < 0.05 (FWE corrected at the cluster level) after small volume correction (SVC) using anatomical masks of the respective regions. For both contrasts, we applied an extent threshold of > 10 voxels. All coordinates are reported in MNI space. Brain regions were labelled according to the AAL toolbox (Automated Anatomical Labeling; Tzourio Mazoyer et al., 2002) implemented in SPM. For simple correlation analyses between psychometric self-reports and the BOLD signal, four Pearson correlations were calculated using the PASW Statistics 18.0 software package (IBM, Switzerland). Scores of depressive symptomatology, neuroticism, self-judgment and cognitive reappraisal were correlated with mean beta values of the a priori defined right superior frontal area. Significance levels were adjusted for multiple tests using the Bonferroni correction (P < 0.0125, one-tailed). Mean beta values were calculated using an in-house programmed MATLAB script. Anatomical masks for the SVC and the correlation analyses were based on the AAL atlas implemented in the WFU PickAtlas (Maldjian et al., 2003, 2004). Because we expected the hippocampus and amygdala to be co-activated (Buchanan, 2007), we created one mask including both structures, which we referred to as the hippocampus–amygdala formation. The anatomical mask for the correlation analyses covered a broad right lateral frontal region including parts of Brodmann areas 6, 8, 9, 10 and 46. We extracted mean beta values from this entire brain region.

Psychometric data

Prior to scanning, participants completed a set of self-report questionnaires. To assess depressive symptomatology in a non-psychiatric population, a validated 15-item German short-version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was administered (Allgemeine Depressionsskala-Kurzform; Hautzinger and Bailer, 1993). In the CES-D participants are asked to appraise different symptoms of depression during the preceding 1-week-interval on a four-point-rating scale. Furthermore, subjects completed the 26-item German version of the Self-Compassion-Scale (SCS-D; Hupfeld and Ruffieux, 2011). Self-compassion entails being kind and understanding towards oneself in instances of pain of failure rather than being harshly self-critical (SCS; Neff, 2003). The questionnaire consists of the six subscales Self-kindness, Self-judgment, Common humanity, Isolation, Mindfulness and Over-identification. In this study, we were especially interested in the five-item Self-judgment subscale (e.g. ‘When I see aspects of myself that I don’t like, I get down on myself’) as it reflects harsh self-critical thinking towards oneself, and the four-item Mindfulness subscale (e.g. ‘When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation’). As the Mindfulness subscale captures cognitive reappraisal strategies as well as related emotion-focused strategies in response to adverse stimuli, we used this scale as a proxy for cognitive reappraisal. In the following we will refer to it as cognitive reappraisal rather than mindfulness. We used the German short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-K; John et al., 1991) to measure neuroticism as a risk factor of depression with four items (e.g. ‘I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well’, reversed scored item). The psychometric properties in the validation samples were satisfactory (Rammstedt and John, 2005). Distributions of the CES-D, Neuroticism, Mindfulness (cognitive reappraisal) and Self-judgment scales are available as Supplementary Material S1.

RESULTS

Behavioural data

Scores on the CES-D ranged from 1 to 11 (mean 4.55; s.d. 3.19), showing that participants’ mood scores generally fell within the normal, healthy range (Hautzinger and Bailer, 1993). The Self-judgment scores ranged from 1 to 3.25 (mean 2.19; s.d. 0.64), average scores indicating low to moderate self-judgment, the Mindfulness scores ranged from 2.25 to 4.25 (mean 3.28; s.d. 0.52), indicating a distribution from low to high cognitive reappraisal (Neff, 2003). Sum scores of Neuroticism (BFI) ranged from 7 to 16 (mean 10.7; s.d. 2.39).

Assessment of individualised self-critical and negative non-self-referential adjectives

On the worksheet including 52 potentially self-critical adjectives, participants chose an average of 8.4 (s.d. = 2.4; min = 6; max = 14) self-critical adjectives. Categories, absolute values, percentages and negativity ratings of the twelve marked prototypes with the harshest self-critical and non-self-referential content are reported in Table 1. Most frequently, adjectives being selected by participants as personally critical belonged to the category dispositions. On the other hand, negative non-self-referential characteristics selected most frequently belonged to the category social and reputational aspects. Moreover, participants rated adjectives describing others as significantly more negative than adjectives describing themselves [t(19) = 8.11, P < 0.001].

Table 1.

Absolute values (percentage) and negativity ratings of self-critical and negative non-self-referential adjectives in corresponding categories

| Categories | Absolute values (percentage) |

Negativity rating |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | Others | Self | Others | |

| Dispositions | 61 (50.83) | 36 (30.00) | Mean = 2.56 (s.d. = 0.69) | Mean = 3.36 (s.d. = 0.79) |

| Social and reputational aspects | 30 (25.00) | 56 (46.67) | Mean = 2.84 (s.d. = 0.95) | Mean = 4.10 (s.d. = 0.58) |

| Temporary conditions | 13 (10.83) | 10 (8.33) | Mean = 2.86 (s.d. = 1.52) | Mean = 3.10 (s.d. = 0.78) |

| Abilities and talents | 9 (7.50) | 10 (8.33) | Mean = 1.81 (s.d. = 1.13) | Mean = 3.22 (s.d. = 0.81) |

| Appearance | 7 (5.83) | 8 (6.67) | Mean = 2.33 (s.d. = 1.03) | Mean = 2.00 (s.d. = 1.10) |

| Total | 120 (100) | 120 (100) | Mean = 2.62 (s.d. = 0.68) | Mean = 3.62 (s.d. = 0.56) |

FMRI data

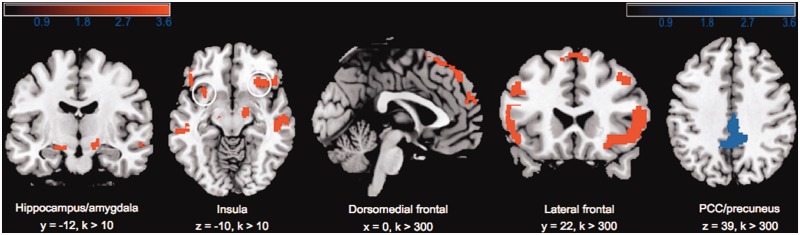

Neural activity in response to self-critical material

Contrast 1 (self-critical > neutral) yielded multiple large clusters reaching our predefined statistical threshold (Table 2; Figure 2). As hypothesised, confrontation with self-critical material elicited activation of the anterior insula and the hippocampus–amygdala formation. In addition, we found two activated clusters in medial superior frontal areas, extending to lateral superior parts of the right frontal lobe. Furthermore, the contrast evoked a significant increase in the BOLD signal in lateral areas of the bilateral inferior frontal cortex, including the pars triangularis and pars opercularis, extending to the orbital frontal cortex and parts of the middle frontal gyrus in both hemispheres. Moreover, we detected significant signal changes in the middle temporal gyrus (MTG) of the right hemisphere and in the left cerebellum (crus II).

Table 2.

Brain areas activated in contrast 1 (self-critical > neutral)

| Anatomical region | Hemisphere | Cluster size | t (df 17) | P corrected | MNI coordinates |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel | Cluster-level | x y z (mm) | |||||

| Lateral superior frontal | Right | 393 | 6.86 | 0.001 | 16 | 52 | 32 |

| Medial superior frontal | Medial | 4.27 | −4 | 52 | 20 | ||

| Medial | 3.92 | −4 | 60 | 24 | |||

| Medial superior frontal | Medial | 592 | 5.35 | 0.000 | 10 | 38 | 46 |

| Medial | 4.99 | −6 | 34 | 52 | |||

| Medial | 4.71 | 0 | 40 | 54 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | Left | 428 | 5.88 | 0.001 | −48 | 22 | 34 |

| Lateral inferior frontal (orbitalis) | Left | 4.74 | −48 | 28 | −10 | ||

| Lateral inferior frontal (triangularis) | Left | 4.19 | −52 | 24 | 0 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | Right | 302 | 5.3 | 0.005 | 40 | 4 | 48 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | Right | 5.2 | 40 | 20 | 42 | ||

| Lateral inferior frontal (triangularis) | Right | 575 | 6.54 | 0.000 | 56 | 22 | −2 |

| Right | 5.23 | 56 | 24 | 12 | |||

| Lateral inferior frontal (orbitalis) | Right | 5.12 | 40 | 24 | −10 | ||

| Medial temporal gyrus | Right | 312 | 5.08 | 0.004 | 64 | −16 | −12 |

| Right | 5.06 | 62 | −24 | −6 | |||

| Right | 4.22 | 52 | −24 | −8 | |||

| Cerebellum (crus II) | Left | 411 | 5.36 | 0.001 | −28 | −74 | −38 |

| Insula | Right | 56 | 5.03 | 0.017* | 40 | 22 | −10 |

| Right | 4.56 | 28 | 24 | −10 | |||

| Right | 4.17 | 46 | 22 | −2 | |||

| Right | 4.06 | 28 | 18 | −12 | |||

| Left | 47 | 5.23 | 0.024* | −30 | 16 | −12 | |

| Left | 4.99 | −32 | 12 | −10 | |||

| Hippocampus–amygdala formation | Left | 18 | 4.74 | 0.042* | −18 | −12 | −14 |

| Left | 3.92 | −14 | −8 | −18 | |||

Clusters significant at P < 0.05 after statistical correction (FWE correction at cluster level) are reported. Multiple peaks within the same label are shown on subsequent lines. Regions are labelled according to the AAL atlas.

*Significant corrected P values shown after SVC.

Fig. 2.

Increased BOLD responses in contrast 1 (self-critical > neutral) are depicted in red and contrast 2 (self-critical > negative non-self-referential) in blue (P < 0.001). Activations are overlaid on a canonical high-resolution structural image in MNI space. The colour bars indicate statistical T variation.

Contrast 2 (self-critical > negative non-self-referential) revealed a significant cluster of activation in the medial PCC with a peak value in the left hemisphere and extending to parts of the precuneus (Table 3; Figure 2). The reverse contrast (negative non-self-referential > self-critical) did not reveal any suprathreshold clusters. Furthermore, contrasting the negative non-self-referential condition with the neutral condition (negative non-self-referential > neutral) did not show significant changes in brain activity.

Table 3.

Brain areas activated in contrast 2 (self-critical > negative non-self-referential)

| Anatomical region | Hemisphere | Cluster size | t (df 17) | P corrected | MNI coordinates |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel | Cluster-level | x y z (mm) | |||||

| PCC | Left | 1294 | 6.79 | 0.000 | 0 | −34 | 28 |

| Right | 6.25 | 2 | −40 | 16 | |||

| Precuneus | Left | 4.67 | −4 | −50 | 40 | ||

Clusters significant at P < 0.05 after statistical correction (FWE correction at cluster level) are reported. Multiple peaks within the same label are shown on subsequent lines. Regions are labelled according to the AAL atlas. PCC = Posterior cingulate cortex.

Correlation of signal changes with psychometric self-reports (contrast 1)

Self-reported neuroticism correlated positively with activation in the right superior frontal area [r(20) = 0.524, P = 0.009]. In contrast, self-reported cognitive reappraisal correlated negatively with activity in the same area [r(20) = −0.507, P = 0.011]. Correlations between scores of depressive symptomatology and activation of the right frontal cortex did not reach significance (significance level of P < 0.0125, Bonferroni corrected), although we observed a trend in the predicted direction [r(20) = 0.378, P = 0.050]. The expected association with levels of self-judgment did not surpass our predefined statistical threshold [r(20) = −0.288, P = 0.109].

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the neural correlates of processing individually tailored self-critical stimuli in healthy subjects. We observed enhanced activation of the hippocampus–amygdala formation and anterior insula when individuals were confronted with self-chosen self-critical adjectives, both structures implicated in emotional responses. Furthermore, healthy subjects seem to apply cognitive emotion regulation strategies via enhanced recruitment of an extended lateral frontal brain network, and they exhibited enhanced activation in the anterior and posterior CMS, which are related to self-referential and autobiographical memory processes.

At the behavioural level, participants rated adjectives describing others as significantly more negative than adjectives related to the self. The above-average effect could provide an explanation for this finding as people have a pervasive tendency to believe that they are better than others in a multitude of ways (Chambers and Windschitl, 2004) and process feedback in a positively biased way (Korn et al., 2012). This widely replicated bias is thought to be driven by strivings for self-enhancement and mood maintenance (Alicke, 1985; Taylor and Brown, 1988; Taylor and Armor, 1996), and this strategy may be a healthy way of dealing with ego-threats.

Contrasting self-critical with neutral stimuli (contrast 1) revealed activation in the anterior insula and the hippocampus–amygdala formation, likely reflecting an emotional response to individualised self-critical material. While, the hippocampus and the amygdala are considered to be co-activated following emotional arousal and retrieval of emotional past experiences (Buchanan, 2007), the anterior insula is recognised for monitoring internal states related to emotional experiences that emerge as conscious feelings (Damasio et al., 2000). Interestingly, Longe et al. (2010) reported insula activation following self-reassurance but not following self-criticism, suggesting that the process of self-criticism may have a more external focus and may exclusively rely on top-down neural processing. A possible explanation for the differing outcomes regarding activation of the insula and limbic structures may be an enhanced emotional involvement during the present task, as participants were not confronted with standardised situation scenarios but individually tailored unpleasant stimuli.

Furthermore, contrast 1 also revealed large bilateral activations of superior and inferior lateral frontal regions. Previous studies reported involvement of the lateral inferior (Aron et al., 2004; Ochsner et al., 2004; Phan et al., 2005; Johnstone et al., 2007) and superior (Davidson, 2000; Ochsner et al., 2002; Phan et al., 2005; Shackman et al., 2009) frontal cortex during inhibition and cognitive emotion regulation. These structures are frequently co-activated during reappraisal and voluntary suppression of negative stimuli, and they are assumed to modulate cortical and subcortical structures (e.g. insula, amygdala and hippocampus) that are involved in emotion experiencing and that are specifically activated in relation to subjective ratings of emotional intensity (see Ochsner and Gross, 2008 for an overview). In previous studies, the superior prefrontal cortex was associated with maintaining and manipulating emotional information in working memory during reappraisal (Northoff et al., 2006; Ochsner and Gross, 2008), and the inferior part seems to be associated with selecting appropriate reappraisals (Denny et al., 2009). Therefore, we conclude that the observed pattern of superior and inferior lateral frontal co-activation might reflect cognitive control for adaptively dealing with self-discrepancies, and this activation may prevent individuals from feeling overwhelmed by negative emotions. Interestingly, Lieberman et al. (2007) reported that the right lateral inferior cortex plays a prominent role in the framework of affect labelling. Given that participants in this study were instructed to silently read the words in their heads, the process of putting feelings into words and thereby applying strategies of affect labelling might have facilitated the reappraisal of threatening material.

Furthermore, we observed activations in the right MTG and the left cerebellum. Anderson et al. (2004) studied brain regions associated with the inhibition of unwanted memories and found evidence that lateral frontal regions interact with the medial temporal lobe in an attempt to suppress memory recollection. The MTG may therefore support the inhibitory pathway mentioned above. Likewise, the crus II of the left cerebellum, an area strongly interlinked with prefrontal areas, is often reported to be co-activated during emotional and cognitive paradigms, as determined by enhanced BOLD signals in this region (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009). We could not detect significant differences comparing the negative with the neutral condition. This suggests that the effect of self-critical processing may go beyond mere negativity.

To control for differing attributes of the stimuli other than self-critical properties (e.g. human vs non-human, or negative/emotional vs neutral), we ran a second contrast (contrast 2, self-critical > negative non-self-referential). This contrast revealed activations in the PCC and in the left precuneus. As participants rated the negative non-self-referential adjectives as more negative than the self-critical adjectives, we also ran the reverse contrast (negative non-self-referential > self-critical). This contrast did not show any significant activation. We argue that evaluative processes related to self-critical attributes differ from evaluative processes related to negative characteristics of other people in intensified recall processes of compatible memories. Previous findings demonstrating that posterior regions of the CMS are strongly involved in episodic memory retrieval (Fink et al., 1996; Cavanna and Trimble, 2006; Northoff et al., 2006; Svoboda et al., 2006; Cabeza and St Jacques, 2007) and studies showing the brain's ability to distinguish real from imaginary memories (Hassabis et al., 2007) are consistent with this interpretation. In addition, activity could also capture differences in emotional intensity due to enhanced self-relevance.

We examined the links between potential risk and/or protective factors of clinical depression and neural activation during confrontation with self-critical stimuli, and we observed a positive association between neuroticism and right superior frontal activity. We also observed a negative association between self-reported cognitive reappraisal and neural activity in the same areas. These results may indicate that highly neurotic yet healthy people require stronger right frontal cortex activation to regulate their negative feelings associated with self-criticism. Conversely, people using cognitive reappraisal strategies more frequently may not need to recruit this region to the same degree to achieve the same level of regulation. Cumulatively, we conclude that without other instructions, healthy people likely apply reappraisal strategies via the activation of a broad lateral frontal network. In addition, the degree of right frontal activation might be moderated by personality traits such as neuroticism and habitual use of cognitive reappraisal strategies. This important modulating mechanism is active in healthy persons but could be less apparent in clinically depressed patients, resulting in failure to activate dlPFC during confrontation with self-referential material (Lemogne et al., 2009), in response to emotional information (Siegle et al., 2007), and during the processing of critical remarks (Hooley et al., 2005, 2009, 2012). This might explain the fact that even after complete remission, formerly depressed individuals experience stronger negative feelings in response to personally significant threats (Hooley et al., 2005, 2009, 2012).

The main limitation of this study lies in the exclusive attribution of the reported activity to self-critical processing. Whereas contrast 2 controlled for stimuli differences such as humanness and negativity, this contrast still fails to control for differences due to self vs other related processing irrespective of valence. To further enhance specificity, an additional condition containing positive self-views would be helpful. Other limitations worth mentioning include first, that the current findings are limited to healthy individuals. To further investigate clinically relevant alterations of the top–down pathway in the context of self-criticism, future studies should include clinically depressed patients. Second, we did not assess information concerning the subjects’ experiences in the scanner. Self-reports about potential mood repair strategies (e.g. reappraisal, self-reassurance, mindful regulation) would provide useful additional information about participants’ top–down strategies. Third, some concerns may be raised regarding the utilised self-report measures as future studies should cover both constructs, neuroticism and cognitive reappraisal, more broadly using multiple measures. Furthermore, given that the right superior frontal region covers a wide anatomical area, a more detailed anatomical specification is required to better understand the roles of personality factors in relation to the activity of specific subsections of this anatomical area.

In summary, the present findings highlight various aspects of self-criticism processing in healthy subjects, including self-referential processing, evoked emotional responses, associated regulatory processes (contrast 1) and self-specific memory processes (contrast 2). Specifically, our data support the central involvement of a broad lateral frontal network in subjects’ dealing with provoked emotional responses, possibly reflecting the recruitment of cognitive reappraisal strategies. Furthermore, right superior frontal areas were moderated by levels of neuroticism and cognitive reappraisal, further supporting the potential clinical relevance of these areas.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at SCAN online.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the subjects who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Dr P. Staempfli, Dr E. Sydekum and P. Kausch, MSc for their valuable practical assistance and help with study procedures. This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation (grant PP00P1-123377/1 to M. Grosse Holtforth and grant PZ00P3_126363 to S. Spinelli) as well as a research grant by the Foundation for Research in Science and the Humanities at the University of Zurich to M. Grosse Holtforth.

REFERENCES

- Alicke MD. Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49(6):1621. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MC, Ochsner KN, Kuhl B, et al. Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories. Science. 2004;303(5655):232. doi: 10.1126/science.1089504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NH. Likableness ratings of 555 personality-trait words. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9(3):272–9. doi: 10.1037/h0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angleitner A, Ostendorf F, John OP. Towards a taxonomy of personality descriptors in German: a psycho-lexical study. European Journal of Personality. 1990;4(2):89. [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8(4):170. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ. Dependency and self-criticism: psychological dimensions of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(1):113. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW. Retrieval of emotional memories. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(5):761. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, St Jacques P. Functional neuroimaging of autobiographical memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(5):219. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Depression and components of self-punitiveness: high standards, self-criticism, and overgeneralization. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92(3):330. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129(3):564. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JR, Windschitl PD. Biases in social comparative judgments: the role of nonmotivated factors in above-average and comparative-optimism effects. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(5):813. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel—now? the anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(1):59. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Argembeau A, Jedidi H, Balteau E, Bahri M, Phillips C, Salmon E. Valuing one's self: medial prefrontal involvement in epistemic and emotive investments in self-views. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22(3):659. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR, Grabowski TJ, Bechara A, et al. Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1049. doi: 10.1038/79871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style, psychopathology, and resilience: brain mechanisms and plasticity. The American Psychologist. 2000;55(11):1196. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny B, Silvers J, Ochsner KN. How we heal what we don't want to feel: the functional neural architecture of emotion regulation. In: Kring AM, Sloan DM, editors. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Etiology and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(2):85. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GR, Markowitsch HJ, Reinkemeier M, Bruckbauer T, Kessler J, Heiss W. Cerebral representation of one’s own past: neural networks involved in autobiographical memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(13):4275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04275.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Hevenor S, Graham S, et al. In search of the emotional self: an fMRI study using positive and negative emotional words. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):1938. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Miles JNV. Sensitivity to Social Put-Down: it's relationship to perceptions of social rank, shame, social anxiety, depression, anger and self-other blame. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29(4):757. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm S, Boesiger P, Beck J, et al. Altered negative BOLD responses in the default-mode network during emotion processing in depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(4):932. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Kumaran D, Maguire AM. Using imagination to understand the neural basis of episodic memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(52):14365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4549-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine Depressionsskala. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins E. Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review. 1987;94(3):319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Gruber SA, Parker HA, Guillaumot J, Rogowska J, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Cortico-limbic response to personally challenging emotional stimuli after complete recovery from depression. Psychiatry Research Neuroimaging. 2009;172(1):83. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Gruber SA, Scott LA, Hiller JB, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Activation in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in response to maternal criticism and praise in recovered depressed and healthy control participants. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(7):809. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Siegle G, Gruber SA. Affective and neural reactivity to criticism in individuals high and low on perceived criticism. PloS One. 2012;7(9):e44412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupfeld J, Ruffieux N. Validierung einer deutschen Version der Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-D) Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2011;40(2):115. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The Big Five Inventory-Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Mitchell KJ, Levin Y. Medial cortex activity, self-reflection and depression. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(4):313. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone T, Van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Failure to regulate: counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(33):8877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WM, Macrae CN, Wyland CL, Caglar S, Inati S, Heatherton TF. Finding the self? An event-related fMRI study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(5):785. doi: 10.1162/08989290260138672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn CW, Prehn K, Park SQ, Walter H, Heekeren HR. Positively biased processing of self-relevant social feedback. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(47):16832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3016-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C, Delaveau P, Freton M, Guionnet S, Fossati P. Medial prefrontal cortex and the self in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(1–2):e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C, Gorwood P, Bergouignan L, Pélissolo A, Lehéricy S, Fossati P. Negative affectivity, self-referential processing and the cortical midline structures. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;6(4):426. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C, le Bastard G, Mayberg H, et al. In search of the depressive self: extended medial prefrontal network during self-referential processing in major depression. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(3):305. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crockett MJ, Tom SM, Pfeifer JH, Way BM. Putting feelings into words affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science. 2007;18(5):421. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longe O, Maratos F, Gilbert P, et al. Having a word with yourself: neural correlates of self-criticism and self-reassurance. NeuroImage. 2010;49(2):1849. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean PD. Psychosomatic disease and the “visceral brain": Recent developments bearing on the Papez theory of emotion. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1949;11(6):338. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. NeuroImage. 2004;21(1):450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19(3):1233. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H. Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35(2):63. [Google Scholar]

- Modinos G, Ormel J, Aleman A. Activation of anterior insula during self-reflection. PloS One. 2009;4(2):e4618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223. [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain? A meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. NeuroImage. 2006;31(1):440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JDE. Rethinking feelings: an fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(8):1215. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. Cognitive emotion regulation: Insights from social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17(2):153. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Ray RD, Cooper JC, et al. For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down-and up-regulation of negative emotion. NeuroImage. 2004;23(2):483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Cahill L. Affective modulation of multiple memory systems. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11(6):752. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(01)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 1937;38(4):725. [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Fitzgerald DA, Nathan PJ, Moore GJ, Uhde TW, Tancer ME. Neural substrates for voluntary suppression of negative affect: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(3):210. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Wagner T, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. NeuroImage. 2002;16(2):331. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004;14(2):198. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A. Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat: a review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;911(1):369. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(5):952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Northoff G. How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? NeuroImage. 2011;57(3):1221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;3:385. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B, John OP. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFI-K) Diagnostica. 2005;51(4):195. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz TW. Relevance to self: a brief review and framework of neural systems underlying appraisal. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2007;31(4):585. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, McMenamin BW, Maxwell JS, Greischar LL, Davidson RJ. Right dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity and behavioral inhibition. Psychological Science. 2009;20(12):1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry SB, Mackinnon SP, Macneil MA, Fitzpatrick S. Discrepancies confer vulnerability to depressive symptoms: a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60(1):112. doi: 10.1037/a0030439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Thompson W, Carter CS, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME. Increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal BOLD responses in unipolar depression: related and independent features. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(2):198. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. NeuroImage. 2009;44(2):489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda E, McKinnon MC, Levine B. The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(12):2189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Armor DA. Positive illusions and coping with adversity. Journal of Personality. 1996;64(4):873. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(2):193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Dent J. Cognitive vulnerability to depression: an investigation of two hypotheses. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1987;26(2):113. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1987.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15(1):273. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren M, Gladwin T, Zandbelt B, Kahn R, Vink M. Reduced functional coupling in the default-mode network during self-referential processing. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(8):1117. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression changes medial prefrontal and ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity associated with self-referential processing. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2013;9(4):487–93. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.