Abstract

Background

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the World Health Organization promoted traditional birth attendant (TBA) training as one strategy to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. To date, evidence in support of TBA training is limited but promising for some mortality outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of TBA training on health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (18 June 2012), citation alerts from our work and reference lists of studies identified in the search.

Selection criteria

Published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCT), comparing trained versus untrained TBAs, additionally trained versus trained TBAs, or women cared for/living in areas served by TBAs.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently assessed study quality and extracted data in the original and first update review. Three authors and one external reviewer independently assessed study quality and two extracted data in this second update.

Main results

Six studies involving over 1345 TBAs, more than 32,000 women and approximately 57,000 births that examined the effects of TBA training for trained versus untrained TBAs (one study) and additionally trained TBA training versus trained TBAs (five studies) are included in this review. These studies consist of individual randomised trials (two studies) and cluster‐randomised trials (four studies). The primary outcomes across the sample of studies were perinatal deaths, stillbirths and neonatal deaths (early, late and overall).

Trained TBAs versus untrained TBAs: one cluster‐randomised trial found a significantly lower perinatal death rate in the trained versus untrained TBA clusters (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 0.83), lower stillbirth rate (adjusted OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83) and lower neonatal death rate (adjusted OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.82). This study also found the maternal death rate was lower but not significant (adjusted OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.22).

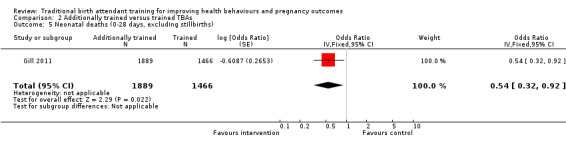

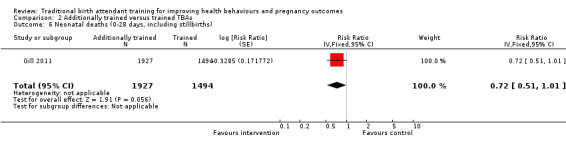

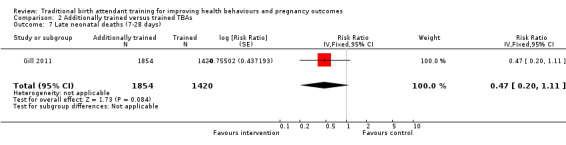

Additionally trained TBAs versus trained TBAs: three large cluster‐randomised trials compared TBAs who received additional training in initial steps of resuscitation, including bag‐valve‐mask ventilation, with TBAs who had received basic training in safe, clean delivery and immediate newborn care. Basic training included mouth‐to‐mouth resuscitation (two studies) or bag‐valve‐mask resuscitation (one study). There was no significant difference in the perinatal death rate between the intervention and control clusters (one study, adjusted OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.02) and no significant difference in late neonatal death rate between intervention and control clusters (one study, adjusted risk ratio (RR) 0.47, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.11). The neonatal death rate, however, was 45% lower in intervention compared with the control clusters (one study, 22.8% versus 40.2%, adjusted RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.92).

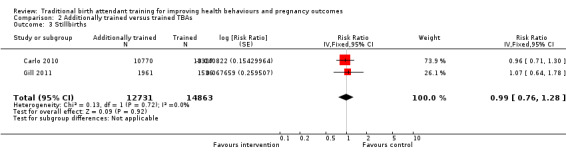

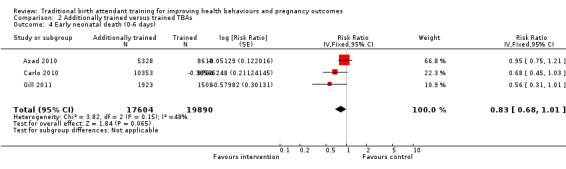

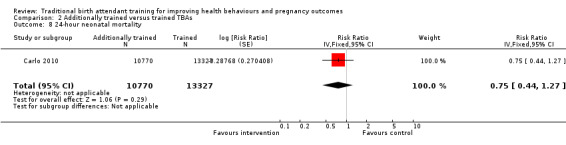

We conducted a meta‐analysis on two outcomes: stillbirths and early neonatal death. There was no significant difference between the additionally trained TBAs versus trained TBAs for stillbirths (two studies, mean weighted adjusted RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28) or early neonatal death rate (three studies, mean weighted adjusted RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.01).

Authors' conclusions

The results are promising for some outcomes (perinatal death, stillbirth and neonatal death). However, most outcomes are reported in only one study. A lack of contrast in training in the intervention and control clusters may have contributed to the null result for stillbirths and an insufficient number of studies may have contributed to the failure to achieve significance for early neonatal deaths. Despite the additional studies included in this updated systematic review, there remains insufficient evidence to establish the potential of TBA training to improve peri‐neonatal mortality.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Infant, Newborn; Pregnancy; Health Behavior; Infant Mortality; Maternal Mortality; Midwifery; Midwifery/education; Midwifery/standards; Perinatal Mortality; Pregnancy Outcome; Pregnancy Outcome/epidemiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stillbirth; Stillbirth/epidemiology

Plain language summary

Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes

Traditional birth attendants are important providers of maternity care in developing countries. Many women in those countries give birth at home, assisted by family members or traditional birth attendants (TBAs). TBAs lack formal training and their skills are initially acquired by delivering babies and apprenticeships with other TBAs. Governments and other organisations have conducted training programmes to improve their skills and to link TBAs to health services. There is disagreement about whether these training programmes are effective. This review included six studies involving over 1345 TBAs, more than 32,000 women and approximately 57,000 births and examined the effect of TBA training, or additional training, on TBA behaviour and on pregnancy outcomes. We conclude that while there are a few more studies meeting the inclusion criteria and the results are promising for some outcomes, more evidence is needed to establish the potential of TBA training to improve peri‐neonatal mortality. A lack of contrast in training in the intervention and control clusters and an insufficient number of studies may have contributed to the lack of observed differences in maternal deaths and deaths of their babies (early neonatal deaths).

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Additionally trained TBAs compared with trained TBAs for stillbirths and early neonatal mortality | |||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women giving birth Settings: home Intervention: additional training Comparison: trained | |||||

| Studies | Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Carlo2010; Gill 2011 |

Stillbirths | RR 0.99 (0.76 to 1.28) | 27,594 births (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | The quality of evidence is moderate. GRADE criteria rates randomised trials as high, but factors such as limitations in blinding, as well as the high likelihood of recruitment and contamination bias in the Gill 2011 study downgrades the evidence to more moderate quality. |

|

Azad 2010; Carlo2010; Gill 2011. |

Early neonatal death (0 to 6 days) | RR 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 37,494 births (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Azad 2010 accounts for two‐thirds of the weight of the evidence. The quality of evidence is moderate. GRADE criteria rates randomised trials as high, but factors such as limitations in blinding, as well as the high likelihood of recruitment bias in the Azad 2010 and Gill 2011 studies, as well as contamination bias in the Gill 2011 study downgrades the evidence to moderate quality. |

| CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; TBAs: traditional birth attendants | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO 1992) defines a traditional birth attendant (TBA) as a person who assists the mother during childbirth and who initially acquires skills by delivering babies herself or through an apprenticeship to other TBAs. Individual TBAs and their roles vary. However, certain characteristics are commonly seen across continents and regions (Fortney 1997a). TBAs tend to be older women, respected in the community for their knowledge and experience. They are often non‐literate and have learned their skills through older, more experienced TBAs. They may work independently, in collaboration with an individual provider or facility or they may be integrated into the health system. Their role may include, in addition to birth attendance, bathing and massage, domestic chores and provision of care during the later postpartum or postnatal period. TBAs may perform other roles depending on local custom, their own interests and expertise. The number of births TBAs attend each year ranges from a few births to as many as 120 births per year. Typically, TBAs attract clients by reputation and word‐of‐mouth. Usually they receive some remuneration for their services.

TBAs are important providers of maternity care in developing countries. Analysis of the 1995 to 1999 Demographic Health Surveys (Measure DHS 2002) using STATCompiler found that TBAs (trained and untrained) assisted at 24% of 200,633 live births (ranging from less than 1% to 66%) in 44 developing countries representing five regions of the world. Reporting on attendance at birth does not clearly distinguish between a TBA, a family TBA (one who has been designated by an extended family to attend births only in that family) or a relative who occasionally attends birth. When these categories are combined, TBAs, relatives and others assisted at 43% of all live births, ranging from less than 1% to 89% of live births. Up to 12% of births are unassisted in some settings (Sibley 2004a). Our re‐analysis of the 2005 to 2009 Demographic and Health Surveys (Measure DHS 2011) using STATCompiler for 20 sub‐Saharan African countries shows that 42% of births from 2002 to 2006 were attended by semi‐ or unskilled attendants (TBAs and relatives/others attend 26% and 17% of births, respectively, while 6% of births were unattended). These statistics are similar for five South Asian countries, where 53% of births are attended by unskilled or semi‐skilled attendants (TBAs attend 23% of births, relatives/others 28% and 2% are unattended).

Maternal mortality estimates for 2005 (WHO 2007) indicated that approximately 536,000 women die each year from causes related to childbearing; 99% in developing countries, mostly due to direct obstetric causes including severe bleeding (haemorrhage), infection, complications of unsafe abortion, eclampsia and obstructed labour (Khan 2006). Although more recent estimates show that a number of countries have made progress and are on track to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 to reduce the maternal mortality ratio by three‐quarters, sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia together still carry the greatest burden of death, with 87% of maternal deaths (WHO 2010b).

An estimated 4 million babies die within four weeks of birth, mostly (75%) within the first week and on the first day of life; a similar number of babies are stillborn. Like maternal mortality, 99% of neonatal deaths take place in developing countries, mostly due to preterm birth, severe infections and asphyxia (Lawn 2005; WHO 2006). Although progress has been made towards MDG 4 to reduce the under‐five mortality rate by two‐thirds between 1990 and 2015, this is primarily due to reductions in child mortality. To achieve MDG 4, reductions in neonatal mortality are also necessary. The highest numbers of neonatal deaths are in south‐central Asian countries and the highest rates are generally in sub‐Saharan Africa. Most countries in these regions have made little progress in reducing these deaths (Lawn 2005; WHO 2006). Stillbirths and early neonatal deaths have similar obstetric origins and could be largely prevented, highlighting the importance of skilled care during labour, delivery and the early postnatal period for both mothers and babies (WHO 2006).

During the 1970s through to the 1990s, the World Health Organization promoted training of TBAs as a major public health strategy to reduce this tragic and preventable loss of life. According to the WHO (WHO 1992), a trained TBA is any TBA who has received a short course of training through the modern health sector to upgrade skills. The broad goals of TBA training were to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality and to improve the reproductive health of women. Objectives included enhancing linkages between modern healthcare services and the community, increasing the number of TBA‐attended births, and improving TBA skills and stature. Training programmes differed considerably in the way in which they address these objectives (Fortney 1997a). TBAs were trained by individuals, non‐governmental organisations and missions, as well as by local, state and national governments. The training programmes ranged from very basic to quite elaborate and may last from several days to several months. They may, but often did not, include clinical practice at a referral facility. They may, but sometimes did not, include continued contact with trained TBAs through supervision and further education. The content of TBA training also varied but usually includes performance of hygienic deliveries and cord care and use of appropriate techniques for delivery of the placenta to prevent immediate postpartum haemorrhage. Consistent with the emphasis on extending the reach of primary health care, however, many TBAs were also trained to take on expanded functions focusing on prevention, screening and referral. Usually TBAs were not trained to provide initial management for major maternal and neonatal complications such as postpartum haemorrhage or birth asphyxia (Sibley 2004c). Moreover, TBAs typically practised in resource‐poor environments where access to and availability of quality emergency obstetric care are severely constrained. Thus, their ability to impact maternal and neonatal mortality was limited. After more than three decades of experience, the evidence to support TBA training was limited and conflicting. By the late 1990s the uncertain impact of TBAs on maternal and neonatal mortality stimulated a passionate policy debate over the cost‐effectiveness of TBA training (Bang 1994; Bang 1999; Bergstrom 2001; Fortney 1997a; Kumar 1998; Levitt 1997; Maine 1992, Maine 1993; Rahman 1982; Sibley 2004a; Starrs 1998; Tinker 1993; UNICEF 1997; WHO 1992). Since the mid‐1990s, international policy has promoted skilled birth attendance. At the same time, countries with the highest maternal and neonatal mortality are often challenged by maternal and neonatal health workforce shortages, poor performance, inequitable distribution and high costs. These countries have, perhaps by default, a greater proportion of births attended by TBAs, relatives and others. While recognising the critical importance of skilled birth attendance in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, concern persists among policy makers and planners about what to do about TBAs (and other less skilled health workers) during the transition to skilled birth attendance.

Rigorous evaluation of TBA training is methodologically and logistically challenging. The distinction between a trained TBA and an untrained TBA may be blurred because untrained TBAs are exposed frequently to biomedical concepts and practices. Moreover, TBA training is often one component of comprehensive interventions, for example, community mobilisation and upgrading of referral facilities. Both behavioural and health outcomes such as maternal and neonatal morbidity are typically based on self report and suffer the limitations of this method (Filippi 2000; Fortney 1997b; Ronsmans 1997). Finally, measuring the magnitude of the impact of TBA training on maternal mortality requires special studies with large bio‐statistical denominators. As a result, while donors, governments and non‐governmental organisations have invested heavily in TBA training programmes over the years, they have not invested equally in the systematic evaluation of training effectiveness (Fortney 1997b; Miller 2003).

Two of the review authors (LM Sibley, TA Sipe) conducted a meta‐analysis for the period 1970 to 1999 on the effect of TBA training and a subsequent update through 2002 (Sibley 2002; Sibley 2004c). The original systematic review included 60 eligible studies measuring 1695 unique outcomes reflecting attributes of knowledge, attitude, behaviour and advice (a subset of behaviour) related to maternal and child health care (MCH), as well as maternal and perinatal mortality. The studies span 30 years and three world regions. Main findings include moderate to large, positive effects for MCH knowledge, attitudes, behaviour and advice associated with training and small effects associated with perinatal health outcomes, such as cause‐specific neonatal mortality due to birth asphyxia, which demonstrated an 11% decrease over the untrained TBA baseline). The data were not sufficient to document an association between training and maternal mortality (Sibley 2002; Sibley 2004c). The 2004 updated systematic review (n = 16) included a stratified analysis to examine the influence of methodological variables and outcomes pertaining to antenatal care service (Sibley 2004a) and emergency obstetric care (Sibley 2004b). Main findings from the systematic review include a medium, positive, but non‐significant association between training and knowledge of risk factors and health conditions requiring referral (danger signs); with small, positive, significant associations between training and TBA referral behaviour (a 36% increase over the untrained TBA baseline), as well as maternal service use (a 22% increase over the untrained TBA baseline). These findings suggest that the real effects of TBA training on TBA and maternal referral behaviour are likely to be small, and emphasise the complexity of the referral process (Sibley 2004b). Unfortunately, the overall quality of studies included in this systematic review did not permit causal attribution to training. Even in the more rigorous studies, TBA training was part of an integrated package of interventions in an integrated package of interventions (Sibley 2002; Sibley 2004c). Thus, countries that are considering current and future TBA training do not have adequate evidence needed to guide sound policy and programme decisions. As others have persuasively argued (Buekens 2003; Miller 2003), rigorous evaluation is both necessary and feasible. Our original and first update of this review (2007, 2009) included four studies. We concluded that the potential of TBA training to reduce peri‐neonatal mortality is promising when combined with improved health services. However, the number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was insufficient to provide the evidence needed to establish training effectiveness.

Responsive to the reality that lay health workers and TBAs continue to provide maternal and neonatal health in high mortality countries, the WHO has initiated consultative steps towards developing guidance for Member States on optimising the roles and capacity of frontline workers (including lay health workers and TBAs) as a possible strategy for scaling‐up implementation of evidence‐based care practices to achieve Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 (WHO 2010a). With the addition of three new large cluster‐randomised trials, we hope that this 2011 update review on TBA training effectiveness will contribute evidence that is needed for guidance on TBA training.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to assess the effects of traditional birth attendant (TBA) training on TBA and maternal behaviours thought to mediate positive pregnancy outcomes, as well as on maternal, perinatal and newborn mortality and morbidity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (including cluster‐randomised trials).

In previous versions of the review we also considered studies with other types of design (interrupted time series and controlled before and after studies). In view of the increasing evidence from randomised trials, in this updated review inclusion criteria for types of studies has been restricted to randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

This review uses the World Health Organization (WHO 1992) definition of a traditional birth attendant (TBA), which defines a TBA as a person who assists the mother during childbirth and who initially acquired her skills by delivering babies herself or through an apprenticeship to other TBAs. Eligible participants include:

trained and untrained TBAs as well as additionally trained and trained TBAs (reference to target intervention);

mothers and neonates cared for by trained and untrained TBAs as well as additionally trained and trained TBAs (or those who are living in areas where such TBAs attend a majority of births ‐ a proxy for exposure of women to TBAs); or

areas (or communities) having #1 and #2 (in the case of cluster‐randomised trials).

Only studies where the participants were TBAs and/or mothers and neonates in the care of TBAs were considered for inclusion. Studies with interventions that did not include TBAs or those in their care were excluded.

Where available, we provide information on the following characteristics of participants: TBA age, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, number of deliveries per year and number of years of practice, as well as maternal age, parity, socioeconomic status and educational attainment.

Types of interventions

TBA training is the intervention of interest.

Where available, we provide information on the following characteristics of the intervention: training method, content, duration, contact hours, trainer/trainee ratio, supervision and continuing education after training; whether training is a single intervention or a component of a complex intervention; as well as whether training was implemented in the context of an enabling environment that include elements such as advocacy, community mobilisation, emergency transportation or referral sites capable of emergency obstetric and newborn care.

Only studies with interventions that included TBA training were considered. Studies with interventions that did not include TBA training were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Measure of maternal mortality:

maternal death (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births).

2. Measures of peri‐neonatal mortality:

stillbirth (number per 1000 live births);

early neonatal death (number 0 to 7 days per 1000 live births);

late neonatal death (number 8 to 28 days per 1000 live births);

neonatal death (number 0 to 28 days per 1000 live births); and

perinatal death (number stillbirths + live births 0 to 7 days per 1000 live births).

Secondary outcomes

1. Measures of maternal morbidity. We included studies containing outcomes based on self report of conditions in which a TBA's or woman's behaviour could affect the occurrence or severity of the condition, as long as the studies specify accepted case definitions or diagnostic criteria; for example, studies using or modifying the WHO verbal autopsy method (WHO 1995). The following conditions include:

prolonged or obstructed labour (> 24 hours duration of labour);

postpartum haemorrhage (> 500 ml blood loss following vaginal birth); and

postpartum infection.

2. Measures of peri‐neonatal morbidity. As with maternal morbidity, we included studies containing outcomes based on self report of conditions in which a TBA's or woman's behaviour could affect the occurrence or severity of the condition, as long as the studies specify accepted case definitions or diagnostic criteria (Marsh 2003; WHO 1999). The following conditions include:

low birthweight (< 2500 grams at birth);

birth asphyxia (failure to breathe within one minute of birth); and

infection (systemic, acute respiratory infection, tetanus).

3. TBA or maternal behaviours, or both, thought to mediate positive pregnancy outcomes include:

TBA advice to use or distribution of antenatal iron folic acid, or maternal use of antenatal iron folic acid supplementation;

TBA advice to use or distribution of vitamin A, or maternal use of antenatal and postnatal vitamin A supplementation;

TBA advice to use or distribution of malaria prophylaxis, or maternal use of malaria prophylaxis;

TBA advice to be immunised against tetanus, or maternal acceptance of tetanus immunisation;

TBA use of hygienic delivery practices, advice to use hygienic delivery practices, or maternal use of hygienic delivery practices;

TBA advice regarding or maternal initiation of early and exclusive breastfeeding, or both;

TBA home‐based management of selected life‐threatening conditions (listed below);

completed referral to health facility for emergency obstetric or neonatal care (where facilities exist and such care is available), or both;

TBA advice to use or maternal use of family planning; and

TBA advice to use or maternal use of antenatal and postnatal care.

We provide information for characteristics of outcome measures such as the timing of observation relative to the intervention, as well as data collection method and data source, where available.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (18 June 2012). For details of supplemental searches we have conducted for previous versions of the review, seeAppendix 1.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched citation alerts from our work and reference lists of studies identified in the search.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 3.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion. We did not require third person consultation.

Data extraction and management

We used the form designed for the original review to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and did not require third‐person consultation. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. In addition we used items specific for cluster‐randomised trials when appropriate (see Handbook sections 16.3.2 and 16.4.3). In the following section, we describe the criteria used to assess risk of bias for the different types of study designs.

A. Individually randomised controlled trials

1. Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. We assessed the method as:

low risk (any truly random process, e.g., random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk (any non‐random process, e.g., odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk.

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (e.g., telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk.

3. Blinding (checking for possible detection and performance bias)

We describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We assessed the methods as:

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for participants;

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for personnel;

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for outcome assessors.

4. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. We assessed data as low risk if there was no more than 20% missing data. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk.

5. Selective reporting bias (checking for reporting bias)

We describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk.

6. Other sources of bias

We describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias. We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk.

B. Cluster‐randomised trials

1. Recruitment bias

Recruitment bias can occur when individuals are recruited to the trial after the clusters have been randomised, as the knowledge of whether each cluster is an ‘intervention’ or ‘control’ cluster could affect the types of participants recruited. We assessed the methods as:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk.

2. Baseline imbalance

Cluster‐randomised trials often randomise all clusters at once, so lack of concealment of an allocation sequence should not usually be an issue. However, because small numbers of clusters are randomised, there is a possibility of chance baseline imbalance between the randomised groups, in terms of either the clusters or the individuals. Baseline differences can be reduced by using stratified or pair‐matched randomisation of clusters or statistical adjustment. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (comparable groups in terms of clusters individuals or statistical adjustment in the analysis);

high risk;

unclear risk.

3. Loss of clusters

Occasionally complete clusters are lost from a trial, and have to be omitted from the analysis. Just as for missing outcome data in individually randomised trials, this may lead to bias. Missing outcomes for individuals within clusters may also lead to a risk of bias in cluster‐randomised trials. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (no loss of clusters, < 20% loss of individuals, < 20% missing data on primary outcomes);

high risk;

unclear risk.

4. Incorrect statistical methods (unit of analysis error)

Cluster‐randomised trials are sometimes analysed by incorrect statistical methods, not taking the clustering into account. Such analyses create a ‘unit of analysis error’ and produce over‐precise results (the standard error of the estimated intervention effect is too small) and P values that are too small. They do not lead to biased estimates of effect. However, if they remain uncorrected, they will receive too much weight in a meta‐analysis. We assessed the methods as:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk.

C. Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) for individually randomised trials and (1) to (4) for cluster‐randomised controlled trials, above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated effect sizes for each outcome reported in individual studies. We calculated summary effect estimates for similar outcomes reported by two or more studies.

Dichotomous data

For individual studies reporting dichotomous data, we used the odds ratios or risk ratios provided by the authors and entered the data into RevMan using the inverse variance method. When necessary we calculated effect estimates from raw data provided by the authors and we present data that the authors report as well (e.g., percentages). Because most of the studies reported cluster‐adjusted outcomes, we were unable to transform all of the effect sizes into a common metric.

Continuous data

For individual studies reporting continuous data, we calculated the mean difference and 95% confidence intervals. We provide the data that the authors report as well (e.g., group means, standard deviations (SDs)).

Unit of analysis issues

We stratified on the type of comparison group in our analysis. We analysed studies comparing trained versus untrained TBAs separately from studies comparing additionally trained versus trained TBAs. We included four cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with two individually randomised trials. All of the cluster trials used an appropriate method of analysis to handle the cluster level by either calculating an intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) (Azad 2010; Carlo 2010) or by using multilevel modelling to adjust for cluster randomisation (Gill 2011; Jokhio 2005). We calculated effect sizes using the inverse variance method described in the Handbook (Section 16.3.3). For the two outcomes we were able to combine, measures of heterogeneity did not exceed the threshold (I² < 50%).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect with a sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e., we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T² was greater than zero and if either I² was greater than 50% or there was a low P value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

There were six included studies in this update of the review. As such, we did not investigate reporting bias beyond the level of the individual study. In future updates of this review, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually, and use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry is detected in any of these tests or is suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e., where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. We were able to combine studies for two outcomes: stillbirths and early neonatal deaths. We combined results only from studies having similar comparison groups and similar designs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analysis for primary outcomes, stratifying on participant and intervention characteristics.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes included in meta‐analyses when there were sufficient numbers of studies. Specifically, we planned a one‐study‐removed analysis to determine if any one study has an undue influence on results. Other sensitivity analyses were planned as needed once the data were examined, e.g., impact of level of bias on treatment effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original review electronic searches yielded a total of 147 citations, including three citations from the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register, 113 from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group's Trials Register and 43 citations from the supplemental search. We screened the studies in two stages. First, two members of the review team independently screened the titles or abstracts from these citations, reaching 99% agreement. They discussed and resolved differences of opinion, where possible, and eliminated all studies which they agreed did not meet preset criteria for types of participants, interventions and outcome measures. We obtained the full text documents of 18 studies. Second, two different members of the team independently read the full text and screened all 18 studies according to the preset criteria for types of studies, reaching 94% agreement. Differences of opinion were discussed and resolved in favour of including four and excluding 14 studies from the review (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies table). In addition, a staff member from the Cochrane EPOC Group reviewed the studies under disagreement and provided a third opinion regarding eligibility.

For this 2012 update, we followed the same search strategy used in the original review, but did not update the supplemental search. We also screened citation alerts from our publications on this topic. The updated electronic searches yielded a total of 28 citations. We reached consensus in favour of including three studies and excluding nine studies from the review. Four trial reports are awaiting classification (Costello 2011; Matendo 2011; Morrison 2011; Pasha 2010).

In this update we changed the inclusion criteria for types of studies and now include only randomised or quasi‐randomised trials; one controlled before and after study that was previously included has now been excluded (O'Rourke 1994).

This review is now comprised of six included studies and 24 excluded studies.

Included studies

The six included studies covered a period of 22 years and included four large cluster‐randomised controlled trials from Bangladesh (Azad 2010); the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guatemala, India, Pakistan, Zambia (Carlo 2010); Zambia (Gill 2011); and Pakistan (Jokhio 2005), along with smaller individual randomised controlled trials from Malawi (Bullough 1989) and Bangladesh (Hossain 2000). The six studies include five papers published in peer‐reviewed journals and an unpublished technical report of operations research (seeCharacteristics of included studies table).

Participants

Participants included traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and lactating mothers living in the intervention and control areas (Hossain 2000), pregnant women living in the intervention and control clusters identified, recruited and followed through the postpartum and/or postnatal periods (Azad 2010; Carlo 2010; Jokhio 2005), and women recently delivered by and/or referred to a health facility by TBAs (Bullough 1989; Gill 2011). See 'Characteristics of TBAs' (Table 2) and 'Characteristics of women' (Table 3) for available social and demographic information about the study populations.

1. Characteristics of traditional birth attendants (participants).

| Study ID (year) | Sample | Age (years) % | Educational level % | Marital status % | Other sources | Experience (years) % | Prior training % | Place of training |

| Azad 2010 | Intervention and control: n = 482 |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Intervention: Yes = 100 Control: Yes = 100 |

Not reported |

| Bullough 1989 | Intervention: n = 2104 Control: n = 2123 |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Intervention: Yes = 100 Control: Yes = 100 | Not reported |

| Carlo 2010 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Intervention: Yes = 100 Control: Yes = 100 | Not reported |

| Gill 2011 | Intervention: n = 60 Control: n = 67 |

Intervention: mean = 49.2, SE = 0.79 Control: mean = 49.6, SE = 1.32 |

Intervention: None = 5 Some primary = 78 Some secondary = 17 Mean = 6.3 Control: None = 29 Some primary = 62 Some secondary = 9 Mean = 4.3 |

Intervention: Married = 70 Single = 2 Divorced = 13 Widowed = 15 Control: Married = 81 Single = 2 Divorced = 2 Widowed = 16 |

Not reported | Intervention: mean = 6.3, SE = 0.48 Control: mean = 4.0, SE = 0.55 |

Intervention: Yes = 100 Control: Yes = 100 | Not reported |

| Hossain 2000 | Intervention n = 85 Control n = 86 |

Intervention = < 30 = 3.3 30 to 39 = 24.4 40 to 49 = 38.9 50 to 59 = 23.3 60+ = 10.0 Control: < 30 = 1.2 30 to 39 = 19.8 40 to 49 = 45.7 50 to 59 = 21.0 60+ = 12.3 | Intervention: < Primary = 72.2 Class 5 to 9 = 26.7 SSC = 1.1 HSC = 0.0 Control: < Primary = 71.6 Class 5 to 9 = 24.7 SSC = 2.5 HSC = 1.2 | Intervention: Married = 67.8 Unmarried = 0.0 Widow = 32.2 Control: Married = 63.0 Unmarried = 1.2 Widow = 35.8 | Intervention: Nothing = 36.7 Work in = Other house = 5.6 Small business = 2.2 Poultry rearing = 35.6 Cow rearing = 3.3 Other = 16.7 Control: Nothing = 46.9 Work in = Other house = 1.2 Small business = 3.7 Poultry rearing = 28.4 Cow rearing = 0.0 Other = 19.8 | Intervention: < 10 = 45.6 10 to 19 = 31.0 20 to 29 = 16.7 30+ = 6.7 Control: < 10 = 33.3 10 to 19 = 46.9 20 to 29 = 17.3 30+ = 2.5 | Intervention: Yes = 96.7 Control: Yes = 70.4 | Not reported |

| Jokhio 2005 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

HSC: Higher School Certificate SE: standard error SSC: Secondary School Certificate

2. Characteristics of women (participants) served by traditional birth attendants.

| Study ID (year) | Sample | Age in years (%) | Parity (%) | Education (%) | Marital status (%) | SES (%) | Other (%) |

| Azad 2010 | Intervention n = 12,519 home births (8618 attended by any TBA and 2792 attended by TBA trained in bag‐valve‐mask resuscitation) Control n = 13,195 home births (9171 attended by any TBA and 2536 attended by TBA trained in bag‐valve‐mask resuscitation) Intervention n = 3213 women Control = 3176 women |

Intervention: < 20 = 16 20 to 29 = 65 > 30 = 19 Control: < 20 = 13 20 to 29 = 60 > 30 = 26 |

Not reported | Intervention: None = 59 Primary = 32 Secondary or more = 18 Control: None = 48 Primary = 28 Secondary or more = 24 |

Not reported | Intervention: Own agricultural land = 49 Own house = 98 Own appliances (wardrobe, radio, sewing machine, bicycle) = 30 Own none of above appliances = 10 Use of sanitary latrine = 32 Access to tube well = 97 Control: Own agricultural land = 49 Own house = 96 Own appliances (wardrobe, radio, sewing machine, bicycle) = 44 Own none of above appliances = 8 Use of sanitary latrine = 46 Access to tube well = 95 |

NGO membership Intervention: 27 Control: 32 Religion Intervention: Islam = 88 Hindu = 12 Control: Islam = 81 Hindu = 19 |

| Bullough 1989 | Intervention n = 2104 Control n = 2123 |

Not reported | Intervention: primigravida = 12.0 1 to 3 = 40.3 4 to 6 = 29.4 > 7 = 12.4 Unknown = 6.0 Control: primigravida = 13.6 1 to 3 = 41.5 4 to 6 = 1.0 > 7 = 12.2 Unknown = 1.7 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Carlo 2010 | Intervention: 10,770 women delivered by TBA Control: 13,327 women delivered by TBA |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gill 2011 | Intervention: 1920 women Control: 1517 women |

Intervention: 25.3 Control: 25.3 |

Not reported | Intervention: No formal = 16.9 Some primary = 68.9 Some secondary = 13.9 Some higher = 0.3 Control: No formal = 18.5 Some primary = 69.3 Some secondary = 11.8 Some higher = 0.4 |

Intervention: Married = 89.0 Widowed = 0.9 Sep/div = 2.5 Never married = 7.6 Control: Married = 90.1 Widowed = 0.6 Sep/div = 2.7 Never married = 6.6 |

Not reported | Mean # people living in household Intervention: 5.2 Control: 5.3 Mean # ANC visits Intervention: 3.3 Control: 3.2 Content of ANC received Intervention: Malaria tx = 88.7 Deworm = 65.2 Folic acid = 85.0 Iron = 91.6 TT = 72.0 Control: Malaria tx = 87.4 Deworm = 64.0 Folic acid = 83.8 Iron = 91.8 TT = 72.4 |

| Hossain 2000 | Intervention n = 354 Control n = 360 | Intervention: < 20 = 15.9 20 to 29 = 62.9 30 to 39 = 19.8 40 to 49 = 1.5 Control: < 20 = 20.7 20 to 29 = 57.7 30 to 39 = 19.9 40 to 49 = 1.6 | Total children. Intervention 1 to 2 = 61.7 3 to 4 = 25.1 5 to 6 = 10.5 7+ = 2.7 Control: 1 to 2 = 57.5 3 to 4 = 31.5 5 to 6 = 8.7 7+ = 2.4 | Intervention: No school = 46.7 Class 1 to 4 = 21.0 Class 5 to 6 = 27.2 SSC = 4.2 HSC = 0.9 Control: No school = 45.9 Class 1 to 4 = 15.0 Class 5 to 6 = 31.0 SSC = 6.8 HSC = 1.3 | Not reported | Housing structure. Intervention: Jhupri = 3.6 One room of clay/bamboo/straw = 26.0 More than one room of clay/bamboo/straw = 10.2 Tin‐roofed house = 55.4 Concrete = 3.9 Shelter = 0.9 Control: Jhupri = 3.7 One room of clay/bamboo/straw = 27.8 More than one room of clay/bamboo/straw = 9.7 Tin‐roofed house = 52.2 Concrete = 5.0 Shelter = 1.6 | Not reported |

| Jokhio 2005 | Intervention n = 10,114 Control n = 9443 | Intervention:

mean = 26.7

SD = 5.9 Control: mean = 26.0 SD = 6.2 |

Intervention: mean = 3.5 SD = 2.8 Control: mean (no.) = 3.7 SD = 2.9 | Intervention:

mean (yrs.) = 1.1

SD = 2.8 Control: mean (yrs.) = 1.4; SD = 3.2 |

Not reported | Not reported | Distance to nearest health facility (km)

Intervention:

mean (km) = 2.7

SD = 3.0 Control: mean (km) = 2.5 SD = 3.0 |

ANC: antenatal care HSC: Higher School Certificate NGO: non‐governmental organisation SD: standard deviation SES: socioeconomic status SSC: Secondary School Certificate TBA: traditional birth attendant TT: tetanus toxoid tx: treatment

Interventions

In two studies, the authors categorised TBAs targeted by interventions as 'untrained' TBAs (Hossain 2000; Jokhio 2005). However, in one of these studies, the large majority of TBAs in both the intervention and control groups had received some prior biomedical training through government or non‐governmental organisations, or both; for example, 97% of the intervention group TBAs and 70% of the control group TBAs in the Bangladesh study (Hossain 2000) had received prior training. Thus we categorised this study into the additionally trained TBAs versus trained TBAs. In the remaining study (Bullough 1989), all TBAs received some prior biomedical training (seeCharacteristics of included studies table).

In four studies, the interventions consisted of educational instruction in management of normal delivery, timely detection and referral of women and/or newborns with complications, as well as importance of linking women to essential obstetric care services (Azad 2010; Carlo 2010; Gill 2011; Jokhio 2005).

In some of the studies, TBA training was part of a package of interventions including community and improved facility‐based care components. For example, in one study (Jokhio 2005), the improvements involved staff training in essential and emergency obstetric care and clinical outreach by team physicians. Two study interventions focused on breastfeeding: one highlighted initiation of early exclusive breastfeeding and the introduction of weaning foods (Hossain 2000), while the other intervention emphasised initiation of early suckling before placental delivery to reduce postpartum blood loss (Bullough 1989). Finally, the interventions in the three new studies included in this 2011 review (Azad 2010; Carlo 2010; Gill 2011) focused on essential newborn care and resuscitation.

Duration of training among studies ranged from two to three days (Azad 2010; Carlo 2010) to up to one week (Gill 2011). Apart from content and duration, few authors reported other characteristics of the TBA training interventions (see 'Intervention characteristics' (Table 4)).

3. Intervention characteristics of traditional birth attendant training.

| Author (year) | Characteristics | Trainer information | Training modality | Curriculum info | Training focus | Duration/intensity | Trainee information | Post‐training |

| Azad 2010 | Evidence base: bag‐valve‐mask ventilation reduces birth asphyxia mortality Based on clinical practice guidelines: not clear Purpose: improved management, initiation of new management Nature of desired change: improved neonatal resuscitation Source of funding: Women and Children First, UK Big Lottery Fund, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, UK Department for International Development Ethical approval: not clear |

Deliverer: not clear Trainer qualification: not clear Trainers training: not clear Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear |

Theoretical: done Practical: done Format: interpersonal, simulation |

Curriculum source: not clear | Content: all TBAs, clean safe delivery, danger signs emergency preparedness, mouth‐to‐mouth ventilation; intervention TBAs, bag‐valve‐mask resuscitation |

Duration: not clear Total contact hours: not clear |

Trainees per cohort: not clear Total trained in programme year: 482 TBAs, number in intervention and control clusters not clear |

Supervision: not clear Follow‐up: not clear (only for data collection) Continuing education: not clear |

| Bullough 1989 | Evidence base: not done (no evidence that early suckling reduces postpartum blood loss) Based on clinical practice guidelines: not done Purpose: appropriate management Nature of the desired change: initiation of new management Source of funding: charitable trust (Bert Trust, Wellcome Trust) Ethical approval: done (Health Sciences Research Committee/ Malawi Ministry of Health) | Deliverer: not clear

Trainer qualification: not clear Trainers training: not clear Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear |

Theoretical: not clear Practical (clinical): not clear Format: interpersonal, audio/visual |

Curriculum source: developed by/for project, local expert body Curriculum pre‐tested or pilot tested: not clear | Content: record keeping, physiology of 3rd stage labour, management of 3rd stage labour, causes of haemorrhage, measurement of blood loss, reason for referral of 3rd stage labour complication plus early sucking for the intervention group | Duration: 2 days Total contact hours: not clear | Trainees per cohort: 6 to 7 TBAs Total trained in programme year: 69 TBAs | Supervision: community midwives Follow‐up: monthly Continuing education: not clear |

|

Carlo 2010 |

Evidence base: done Based on clinical guidelines: done Purpose: improved management and initiation of new management Nature of desired change: basic care and neonatal resuscitation Funding source: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Ethical approval: not clear (but informed consent, data safety and monitoring board) |

Deliverer: local expert Trainer qualification: not clear (experienced) Trainers training: cascade‐trainers trained master trainers, who trained community co‐ordinators Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear |

Theoretical: done Practical: done Format: interpersonal, clinical practice, demonstration, materials adapted for low/non‐literate participants |

Curriculum source: WHO 2004 Essential Newborn Care Program, modified American Academy of Pediatrics Neonatal Resuscitation Program Curriculum pre‐tested or pilot tested: done |

Content: all birth attendants ‐ routine neonatal care, initiation of breathing and resuscitation (bag‐valve‐mask ventilation), thermoregulation, early exclusive breastfeeding, kangaroo care, danger signs. Intervention birth attendants ‐ in‐depth theoretical and practical training in initial steps in resuscitation and bag‐valve‐mask ventilation | Duration: 3 days Essential Newborn Care Program, 3 days Newborn Resuscitation Program Total contact hours: not clear |

Trainees per cohort: not clear Total trained in program year: not clear |

Supervision: not clear (only for data collection) Follow‐up: not clear (only for data collection) Continuing education: 6 mo. refresher for intervention birth attendants |

| Gill 2011 | Evidence base: done Based on clinical guidelines: done Purpose: improved management and initiation of new management Nature of desired change: basic care, resuscitation, sepsis treatment, referral Funding source: Co‐operative agreement, Boston University and USAID, with support from American Academy of Pediatrics and UNICEF Ethical approval: Boston University Medical Center and the Tropical Diseases Research Centre, Ndola, Zambia, informed consent in local languages, data safety monitoring board |

Deliverer: not clear Trainer qualification: not clear (members of the study team) Trainers training: not clear Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear |

Theoretical: done Practical: done Format: lectures, demonstrations, small group sessions and skills practice using infant manikins |

Curriculum source: American Pediatric Association and American Heart Association neonatal resuscitation protocol Curriculum pre‐tested or pilot tested: not clear |

Content: all TBAs trained in prevention of neonatal hypothermia, mouth‐to‐mouth ventilation, record keeping, following up mothers‐newborns Intervention TBAs trained in bag‐valve‐mask ventilation, sepsis management, facilitated referral | Duration: 2 1‐week sessions Total contact hours: not clear |

Trainees per cohort: 60 intervention and 60 control TBAs Total trained in program year: 120 TBAs |

Supervision: not clear (only for data collection) Follow‐up: not clear (only for data collection) Continuing education: not clear |

| Hossain 2000 | Evidence base: done Purpose: appropriate management Nature of the desired change: increase established management Source of funding: voluntary body Ethical approval: not clear | Deliverer: local expert Trainer qualification: not clear Trainers had trainer training: not clear Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear | Theoretical: not clear Practical (clinical): not clear Format: not clear | Curriculum source: developed by/for project, national expert body (Bangladesh Breast Feeding Program) Curriculum pre‐ tested or pilot tested: not clear | Breastfeeding advice including benefits, early, exclusive feeding, introduction/types of complementary weaning foods, disadvantages of bottle feeding | Duration: 2 days Total contact hours: not clear | Trainees per cohort: 15 Total trained in program year: 85 | Supervision: not clear Follow‐up: not clear |

| Jokhio 2005 | Evidence base: not clear (generally accepted best practices) Purpose: appropriate management Nature of the desired change: initiation of new management (new components) Source of funding: government organisation for capital costs (Family Health Project of Sindh Government Health Department) and other for data entry (University of Birmingham, UK) Ethical approval: not clear (protocol discussed and approved after meeting with provincial leaders) | Deliverer: local experts Trainer qualification: paramedics (LHW) and obstetricians Trainers had trainer training: not clear Experience with low or non‐literate trainees: not clear | Theoretical: not clear Practical (clinical): not clear Format: interpersonal, audio/visual | Curriculum source: developed by/for project, local expert body Curriculum pre‐tested or pilot tested: not clear | Advice on antepartum, intrapartum postpartum care, how to conduct clean delivery, how to use disposable delivery kit, referral for obstetric emergencies, newborn care | Duration: 3 days Total contact hours: not clear | Trainees per cohort: not clear Total trained in program year: 565 | Supervision: LHW support and data collection Follow‐up: not clear |

LHW: lady health workers mo.: month TBA: traditional birth attendant

Outcomes

The six studies contained outcomes of maternal deaths, maternal morbidity, perinatal deaths, stillbirths, and early and/or late neonatal deaths, as well as TBA or maternal behaviours thought to mediate positive pregnancy outcomes. Perinatal deaths, stillbirths, early and late neonatal deaths and referral were reported in more than one study. We were able to pool the results for studies containing the outcomes stillbirths and early neonatal deaths in the analysis.

Excluded studies

We excluded 24 studies. The two major reasons for study exclusion were ineligible study design and type of participant (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies table).

Risk of bias in included studies

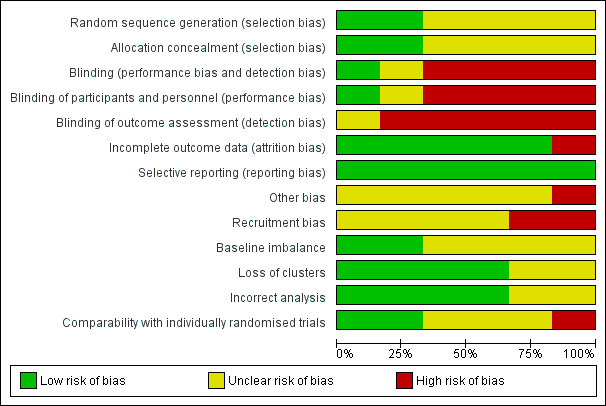

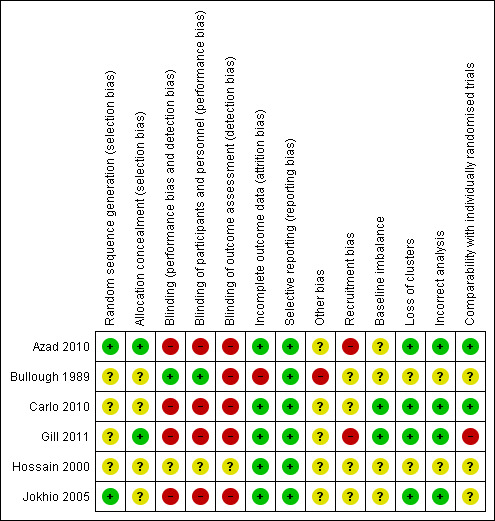

Of the six randomised controlled trials four were cluster‐randomised. No study was low risk of bias for all criteria (seeCharacteristics of included studies) thus all studies were either high risk or unclear risk, meaning that there is some level of plausible bias in each of the studies reviewed or it is unknown if there is bias. Assessment of key criteria and justification for risk level assignation is described in Characteristics of included studies and summarised below. Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide graphical summaries.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Individually randomised and cluster‐randomised controlled trials

1. Random sequence generation

Bullough 1989, Hossain 2000 and Carlo 2010 did not report details on sequence generation for randomisation so the risk of selection bias is unclear for both studies. Azad 2010 and Gill 2011 randomly allocated unions and TBAs, respectively, by drawing slips of paper from a container. However, the Gill 2011 study later added seven TBAs to the control group through a non‐random procedure, and thus the risk of bias is unclear. Jokhio 2005 randomised sub‐districts (talukas) using a computer‐generated randomisation procedure. The allocation sequence in these three studies was decided on before randomisation and before collection and analysis of baseline data.

2. Allocation concealment

Information about allocation concealment procedures used in Bullough 1989, Hossain 2000, Carlo 2010 and Jokhio 2005 was not reported. Risk of selection bias is thus unclear for these studies. The procedure of drawing slips from a container in Azad 2010 and Gill 2011 carried a low risk of bias.

3. Blinding

Bullough 1989 reported that project data collectors were not blinded to the intervention status of the TBAs, but that the TBAs, who measured blood loss, were not informed that they were participating in a trial. Hossain 2000 did not report on blinding of providers, recipients of care or outcome assessors. The risk of performance and detection bias is therefore high for Bullough 1989 and unclear for Hossain 2000.

Blinding of participants and personnel is often not possible for cluster‐randomised trials. Performance bias may be an issue as increased training of TBAs may have instilled greater confidence and adherence from community members for all aspects of care. Carlo 2010, Azad 2010, Gill 2011 and Jokhio 2005 all used TBAs as the primary outcome assessors, with verification of data provided by other unblinded government health workers or interviewers.

Azad 2010 provided a 60 Taka incentive to TBAs for accurate birth/death identification, regardless of whether the TBA was the delivery attendant. However TBAs may have still underreported deaths for deliveries they attended if greater social or reputation disincentives prevailed. Gill 2011 and Jokhio 2005 both used prospective monitoring of pregnant women, which likely reduced detection bias of deaths. Gill 2011 also utilised a panel of independent neonatologists, blinded to group allocation, which reviewed delivery and verbal autopsy reports for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Jokhio 2005 also notes that the Lady Health Workers and TBAs were not made aware of the purpose or comparative nature of the study. We consider the risk of bias due to lack of blinding for all four cluster‐randomised trials to be high.

4. Incomplete outcome data

Bullough 1989 reported that about 30% of TBAs in each group, intervention and control, were excluded from the analysis because they were "untrainable", "failed quality control check", or were "strongly suspected of fabricating results" (page 524). Among the remaining TBAs, outcomes were reported for more than 90% of women. Hossain 2000 reported outcomes for more than 90% of participants. We consider risk of attrition bias to be high for Bullough 1989 and low for Hossain 2000.

None of the four cluster‐randomised control trials had clusters lost to follow‐up. Additionally, all studies reported results for all primary outcomes listed, with a high and comparable percentage for control and intervention clusters (above 80% in all studies). In Azad 2010 only home deliveries were included in the analysis, which is appropriate due to the nature of the intervention. Intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed for all primary and secondary mortality outcomes, yet analysis for behavioural secondary outcomes excluded temporary and tea garden residents. As the only specified outcome for the TBA intervention was early neonatal mortality, there is a low risk of incomplete outcome data. Carlo 2010 excluded births for which the birth weight was unmeasured from the analysis (5.1%), and reported that results were “materially unchanged” with this exclusion.

5. Selective reporting

Reporting bias was low in all studies.

6. Other biases

Bullough 1989 noted that "The accuracy of blood loss measurements by TBAs who were mostly illiterate and/or innumerate may be doubted" (page 524).

Azad 2010 stated that randomisation may be compromised due to the purposive selection of districts, sampling stratification and the restricted number of clusters. Confounding with a women’s group intervention and potentially differential interventions for health services inputs may have also occurred. Underlying secular trends in declining mortality also appeared to be present in control areas. Carlo 2010 reported that participation appeared to be non‐differential between intervention and control. Gill 2011 described various methods for combating misclassification of failed resuscitation as stillbirths. Jokhio 2005 was not sufficiently powered to detect a difference for the maternal mortality outcome. Furthermore, as the outcomes of referrals were not followed, it is possible that the intervention could have altered the composition of referred women (i.e., a greater proportion of high‐risk women electing to be referred), which could have biased results. Finally, the validity of self report of maternal complications may lead to bias.

B. Cluster‐randomised trials only

1. Recruitment bias

Azad 2010 used a factorial design in which clusters were first randomised for a women’s group intervention, then secondarily for the TBA intervention. Women were recruited after the clusters were randomised, placing it at high risk of recruitment bias. Gill 2011 was also at a high risk of bias as seven TBAs (“clusters”) were added to the control group after randomisation. Carlo 2010 and Jokhio 2005 all had an unclear risk of recruitment bias. The method of recruitment was not clearly stated, and the proximity of intervention and control clusters to each other was of concern.

2. Baseline imbalance

All four studies performed a baseline survey and all but Jokhio 2005 controlled for baseline differences in the analysis. In Azad 2010, chance inclusion of three tea garden estates in control clusters, which “had substantially worse health and socioeconomic indicators than did the rest of the study area” occurred, and delayed surveillance activities. The baseline survey found that intervention group mothers were more likely to be younger, have no education and no household assets than control mothers. While baseline differences were adjusted for in the women’s group component of the study, it was unclear whether these differences persisted, or were controlled for, through the second‐level of randomisation for the TBA component of the study. Furthermore, the Jokhio 2005 baseline survey collected data on a limited number of covariates and the comparability of clusters remained unclear. Carlo 2010 and Gill 2011 had comprehensive baseline surveys and large numbers of clusters, thus the risk of baseline imbalance for both was low.

3. Loss of clusters

None of the four studies had loss of clusters.

4. Incorrect analysis

All four studies adjusted for clustering using appropriate methods and are thus at low risk of bias.

5. Comparability with individual trials

Of the four cluster trials, Gill 2011 had a high risk of bias for comparability with individual trials due to apparent contamination of participants from control to intervention clusters. Gill 2011 uniquely defined a cluster by TBA, versus by administrative units like districts. Intervention group TBA catchment areas often overlapped with control group TBA areas, and intervention TBAs attended significantly larger number of deliveries, a figure which increased over the course of the study. Contamination did not appear to be the case for the other studies. However the use of clusters may facilitate natural diffusion of TBA training messages and foster an environment for changes in community‐level knowledge, attitudes and practices. The use of governmental administration units (e.g., sub‐districts) as clusters could also promote cohesion across health system actors and strengthen referral systems. The multiple components of the TBA intervention in Jokhio 2005 seemed particularly aimed at these goals. The implications of these cluster‐level activities made comparability with individual trials unclear.

C. Overall risk of bias

Allocation concealment is generally not a problem for cluster‐randomised control trials as all clusters are randomised at once. However, some authors did not clearly state details for allocation or randomisation sequence, prohibiting judgement on the expected direction and magnitude of the bias.

Lack of blinding of personnel, participants and outcome assessors was problematic across all studies, largely due to the nature of the intervention. This may have resulted in performance bias and detection bias. However, as most of the performance bias expected is due to TBA and communities’ increased confidence in care provided due to the training intervention, this could arguably be considered a valid component of the intervention effect intended. Additionally, it is unclear that detection bias would have been differential between intervention and control clusters. Furthermore the direction of bias could have favoured the control groups, as better‐trained TBAs in intervention clusters may have been able to more accurately detect maternal deaths. Conversely, knowledge of the intervention may have favoured the intervention group, especially for more subjective secondary outcomes such as maternal morbidity or behaviours. Prospective monitoring of pregnant women to minimise issues of disclosure of deaths by both women and TBAs is recommended, as is supervision of TBAs for data collection and follow‐up.

Overall, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting did not appear to be problematic, neither did loss of clusters or incorrect analysis. The largest threat to comparability with individually randomised trials was concerns of a “herd effect” due to natural diffusion of education amongst mothers within intervention clusters and contamination of control cluster participants to intervention clusters due to knowledge of the intervention (also an issue for recruitment bias). The former would overestimate the effect, while the latter may underestimate the effect.

Baseline imbalance was addressed in some way by all four cluster‐RCTs. However, a small number of clusters or incomplete baseline data proved problematic for two studies. In Jokhio 2005 the direction and magnitude of bias due to baseline differences is unclear, as insufficient data on these differences were collected. In Azad 2010 it is unclear in which direction baseline differences may have influenced the effect size, as it was not clear if the authors measured or controlled for these differences during the second level of randomisation for the TBA intervention.

Misclassification bias for stillbirths versus failed resuscitations was another potential source of bias in studies, which would likely underestimate the effect, as better trained TBAs would be more likely to attempt resuscitation. The magnitude of this bias is not clear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Trained traditional birth attendants (TBAs) versus untrained TBAs

Primary outcomes: Mortality

Maternal mortality

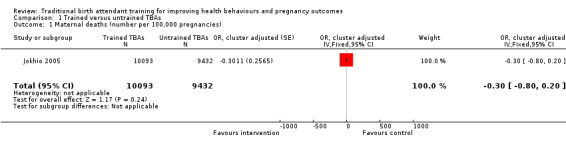

Jokhio 2005 measured maternal mortality and found 27 deaths in the intervention and 34 deaths in the control clusters, corresponding to a 268 and 360 deaths per 100,000 pregnancies, respectively. This 26% difference in favour of women living in the intervention clusters was non‐significant (0.27% versus 0.36%, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45 to 1.22, N = 19,525) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 1 Maternal deaths (number per 100,000 pregnancies).

Stillbirths

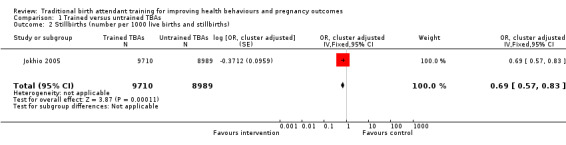

Jokhio 2005 identified 483 and 638 stillbirths in intervention and control clusters, respectively. The stillbirth rate difference was significant, 31% lower in intervention compared with control clusters (5.0% versus 7.1%, adjusted OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83, N = 18,699) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 2 Stillbirths (number per 1000 live births and stillbirths).

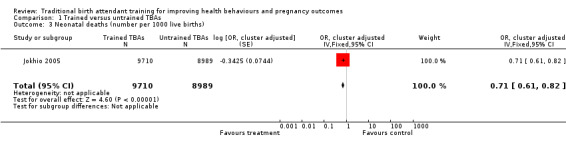

Neonatal death

Jokhio 2005 identified 340 and 349 neonatal deaths in the intervention and control clusters, respectively. The neonatal death rate difference was significant, 29% lower in the intervention compared with the control clusters (3.5% versus 4.88, adjusted OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.82, P < 0.001, N = 18,699) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 3 Neonatal deaths (number per 1000 live births).

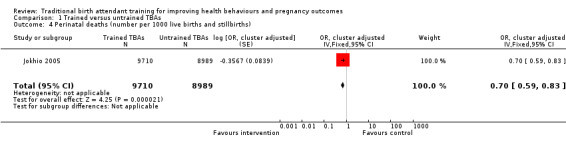

Perinatal death

Jokhio 2005 also measured perinatal death among singleton births and found 823 and 1077 deaths in the intervention and control clusters, respectively, corresponding to 85 and 120 deaths per 1000 live births and stillbirths, respectively. The death rate difference was significant, 30% lower in the intervention compared with the control clusters (8.5% versus 12%, adjusted OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.83, N = 18,699) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 4 Perinatal deaths (number per 1000 live births and stillbirths).

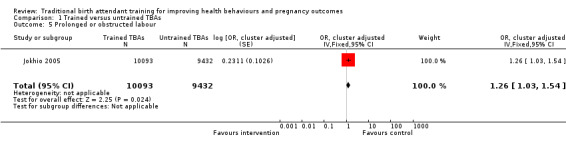

Secondary outcomes: Morbidity

Obstructed labour

Jokhio 2005 found that the frequency of obstructed labour was significantly higher among women living in intervention clusters compared with women living in control clusters (6% versus 5%, adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.54, N = 19,525) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 5 Prolonged or obstructed labour.

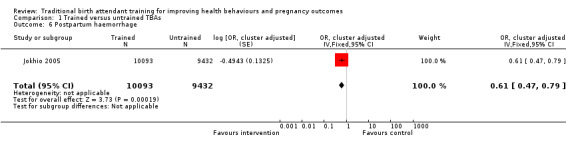

Haemorrhage

Jokhio 2005 found that frequency of haemorrhage (antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum combined) was significantly lower among women living in the intervention clusters, compared with women living in the control clusters (1.7% versus 2.8%, adjusted OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.79, N = 19,525) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 6 Postpartum haemorrhage.

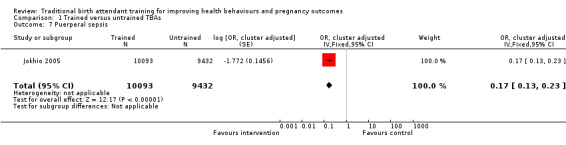

Puerperal sepsis

Jokhio 2005 found the frequency of puerperal sepsis was significantly lower among women living in intervention clusters compared with control clusters (0.8% versus 4.2%, adjusted OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.23, N = 19,525) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 7 Puerperal sepsis.

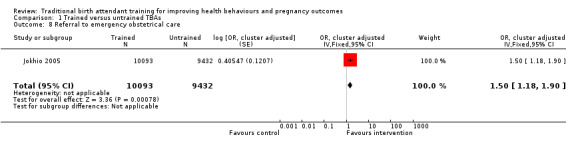

Secondary outcomes: Measures of behaviours

Referral

Although referral rates were low in both intervention and control clusters, Jokhio 2005 found that women living in intervention clusters were significantly more likely to have been referred to any health facility for a complication of pregnancy, delivery or postpartum period, than women living in control clusters; 10% versus 7% respectively (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.50, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.90, N = 19,525) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Trained versus untrained TBAs, Outcome 8 Referral to emergency obstetrical care.

Additionally trained TBAs versus trained TBAs

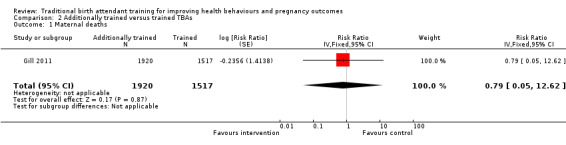

Primary outcomes: Mortality

Maternal deaths

Gill 2011 reported two maternal deaths, one in both the intervention and control groups (unadjusted risk ratio (RR) 0.79, 95% CI 0.05 to 12.62, N = 3437 (Analysis 2.1)).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additionally trained versus trained TBAs, Outcome 1 Maternal deaths.

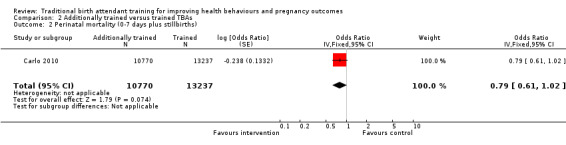

Perinatal death

Carlo 2010 identified 306 and 476 perinatal deaths (defined as stillbirths plus neonatal deaths in first seven days) in the intervention and control clusters, respectively. The perinatal death rate difference was not significant as reported by the author (28.5 versus 35.8 deaths per 1000 births, adjusted RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.02, N = 24,097 (Analysis 2.2)).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additionally trained versus trained TBAs, Outcome 2 Perinatal mortality (0‐7 days plus stillbirths).

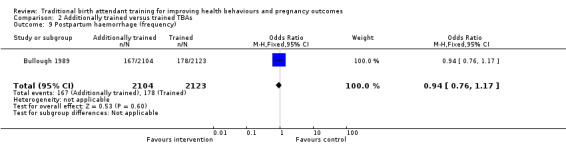

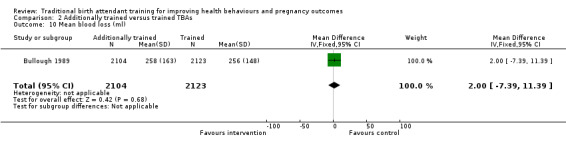

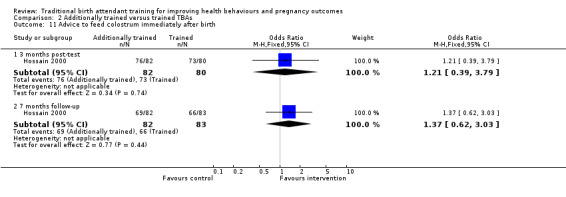

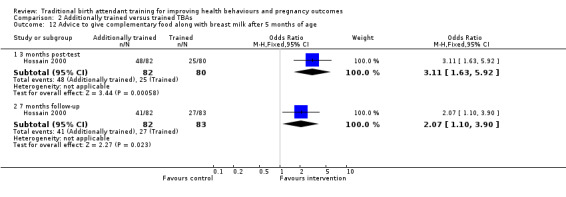

Stillbirth

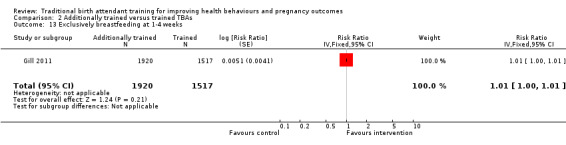

Carlo 2010 also identified 147 and 189 stillbirths in the intervention and control clusters, respectively (13.6 versus 14.2 per 1000 births, adjusted RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.30). Similarly, Gill 2011 identified 38 and 28 stillbirths in the intervention and control clusters, respectively (19.4 versus 18.9 deaths per 1000 births, adjusted RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.77). The overall weighted mean effect estimate was close to 1.0 and not statistically significant (adjusted RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28, N = 27,594) (Analysis 2.3; Figure 3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additionally trained versus trained TBAs, Outcome 3 Stillbirths.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Additional training versus basic training, outcome: 2.4 Stillbirths.

Early neonatal death