Abstract

Interleukin-8 (IL-8) plays key roles in both chronic inflammatory diseases and tumor modulation. We previously observed that IL-8 secretion and function can be modulated by nucleotide (P2) receptors. Here we investigated whether IL-8 release by intestinal epithelial HT-29 cells, a cancer cell line, is modulated by extracellular nucleotide metabolism. We first identified that HT-29 cells regulated adenosine and adenine nucleotide concentration at their surface by the expression of the ectoenzymes NTPDase2, ecto-5′-nucleotidase, and adenylate kinase. The expression of the ectoenzymes was evaluated by RT-PCR, qPCR, and immunoblotting, and their activity was analyzed by RP-HPLC of the products and by detection of Pi produced from the hydrolysis of ATP, ADP, and AMP. In response to poly (I:C), with or without ATP and/or ADP, HT-29 cells released IL-8 and this secretion was modulated by the presence of NTPDase2 and adenylate kinase. Taken together, these results demonstrate the presence of 3 ectoenzymes at the surface of HT-29 cells that control nucleotide levels and adenosine production (NTPDase2, ecto-5′-nucleotidase and adenylate kinase) and that P2 receptor-mediated signaling controls IL-8 release in HT-29 cells which is modulated by the presence of NTPDase2 and adenylate kinase.

1. Introduction

Inflammation is a major contributor to the development and progression of many human cancers [1] and is obviously a key constituent of inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [2–4]. Indeed, a number of chronic inflammatory conditions increase the risk of developing cancers [5]. For instance, IBD is associated with an increased risk of colon cancer development [6, 7]. In addition, the long-term use of anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin decreases the risk of several cancer types [8].

Interleukin-8 (IL-8) or CXCL8 is a proinflammatory chemokine originally identified as a neutrophil chemoattractant [9], which is an important contributor to the induction of innate immunity [10]. Accordingly, IL-8 has been implicated in a number of inflammatory diseases such as IBD [11, 12]. Elevated IL-8 signaling has also been observed within the tumor microenvironment of numerous cancers where it enhances tumor progression via the activation of pathways that promote proliferation, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, and cell survival [13, 14]. Altogether, this suggests that inhibition of IL-8 production could be a potential treatment for both chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer [13, 15]. Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms that drive or mediate IL-8 release is imperative.

We have previously observed that IL-8 secretion, and even function, can be controlled by nucleotide receptors [16–18]. Extracellular nucleotides (e.g., ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP) are secreted by host cells in response to injury, such as in conditions of inflammation, and act as danger signals (alarmins) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These substances initiate the host immune responses [19–21] by activating specific P2 receptors [22]. The concentration of P2 receptor agonists is regulated by ectoenzymes that metabolize nucleotides [23–26]. While ectonucleotidases such as nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (NTPDases) generally terminate P2 receptor activation [24], nucleotide kinases such as adenylate kinase (ADK) may potentiate P2 activation by regenerating the ligand of these receptors from the products of ectonucleotidases [27–29].

In this work, we used HT-29 colon cancer cell line as a model of intestinal epithelial cells (used in IBD models) as well as a model of cancer cells to investigate if, in such cells, ectoenzymes that modulate nucleotide metabolism can control IL-8 secretion. Indeed, HT-29 cells express and secrete IL-8 in response to diverse stimuli [30, 31] such as TLR3 agonists [32]. They also express functional receptors that respond to ATP and/or UTP [33–35] as well as to adenosine [36–42] that are involved in several functions including cell growth and differentiation, and IL-8 release. Our initial objective was therefore to characterize the expression of nucleotide metabolizing ectoenzymes. We identified 3 of these enzymes and 2 of them affected IL-8 release in our system: NTPDase2 which is a predominant ATPase [43] and ADK that catalyzes the reversible transphosphorylation reaction leading to ATP and AMP production from two molecules of ADP as substrate [23]. The ecto-5′-nucleotidase that hydrolyses AMP into adenosine [44, 45] was also highly expressed in these cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

DMEM/F-12 growth medium, Glutamax, Hu IL-8 Cytoset ELISA kit, PureLink Genomic DNA mini kit, Quant-iT RNA BR assay kit, NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris gel, TRIzol reagent, DNAse1-RNAse-free (AM2222), Superscript III reverse transcriptase, RNAseOUT recombinant Ribonuclease inhibitor, dNTP, DTT, aprotinin, Lipofectamine, microAMp optical 384 well reaction plate, custom-made primers, and 1 kb plus DNA ladder were purchased from Life Technologies (Burlington, ON, Canada). Normocin was obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA). ATP, ADP, AMP, adenosine, ATP-γ-S, suramin, diadenosine pentaphosphate (Ap5A), malachite green, and random nonamers (R7647) were purchased from Sigma. Millex GP syringe-driven filter unit 0.22 µm and Immobilon-P membrane were from Millipore (Billerine, MA, USA). Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) with Ca2+ and Mg2+, Hepes, and antibiotic-antimycotic solutions was from Wisent (St. Bruno, QC, Canada). RNeasy mini kit and QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit were from Qiagen (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Taq polymerase was obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA) and FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany).

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

HT-29 (ATCC® HTB-38TM) human colon adenocarcinoma cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in monolayer cultures in DMEM/F-12 growth medium supplemented with Glutamax (2 mM), antibiotic-antimycotic solution (1X), Hepes (25 mM), Normocin (used as an antimycoplasma reagent, 100 μg/mL), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 95% air: 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were regularly monitored for the presence of Mycoplasma spp. by means of a conventional PCR test [47] using 5 μg of extracted genomic DNA (PureLink genomic DNA mini kit) as a template. The cells from passages 2-3 were seeded (2 × 106/well) in 24-well plates containing 1 mL medium. For cell counting and subculturing, cells were dispersed with a 0.25% trypsin solution. Cell viability always exceeded 95%, as measured by Trypan blue dye exclusion.

2.3. IL-8 Production Assays

HT-29 cells were stimulated with suboptimal concentration of poly (I:C) alone or in presence of nucleotides with or without Ap5A as an ADK inhibitor. Stimulations were carried out for 18 h. Media were then collected and centrifuged to remove detached cells and were analyzed for the detection of human IL-8 using the Human IL-8 CytoSet ELISA kit.

2.4. RP-HPLC

HT-29 cells were incubated with ADP or ATP (both at 100 µM) in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing Ca2+ and Mg2+. Where indicated, these incubations were carried out in the presence of the ADK inhibitor, Ap5A (10 µM). At the indicated time points, 100 µL aliquots of medium were sampled, deproteinized with an equal volume of PCA (1 M), and neutralized with KOH (1 M), with all solutions being kept at 4°C. Analysis of the reaction products was performed by RP-HPLC using 15 cm × 3.6 mm, 3 µm SUPELCOSIL LC-18-T columns (Supelco) as described previously [43].

2.5. RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified from HT-29 cells using the RNeasy mini kit and quantified with a Quant-iT RNA BR assay kit and Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies). The cDNA was prepared using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit. For NTPDase screening, semiquantitative amplifications were done with 1 µL cDNA prepared from 3 µg total RNA and Taq polymerase using a PTC-200 Peltier Thermal Cycler in 25 μL reaction volumes and the following program: (i) 2 min at 94°C and (ii) 20 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 75°C (and then decreasing by 1°C/cycle), and 1 min at 72°C, followed by (iii) 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C and (iv) a final 7 min step at 72°C. For the positive controls, 10 pg of miniprep DNA from the expression vectors used for cloning NTPDase1, -3, and -8 were used as templates [48] and due to the location of the primers, 50 ng of HT-29 genomic DNA was used for NTPDase2. For the negative controls, water was used as template. For P2Y receptor screening, using similar conditions for preparation, the program was (i) 2 min at 94°C and (ii) 20 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 72°C (and then decreasing by 1°C/cycle), and 1 min at 72°C, followed by (iii) 20 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 57°C, and 1 min at 72°C and (iv) a final 7 min step at 72°C. For human AK1β amplification, total RNA was extracted and quantified as above, and the cDNA was prepared using 1 μg RNA and Superscript III reverse transcriptase, as specified by the manufacturer. Semiquantitative amplifications were performed as above, except that the amplification program used was (i) 2 min at 94°C, (ii) 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 66.1°C, and 30 sec at 72°C, and (iii) a final 7 min at 72°C. Sequencing of the amplicons was performed by automated DNA sequencing at the Plateforme de Génomique, Protéomique et Bio-informatique, CRCHU, Université Laval.

2.6. qPCR

Total RNA was purified from HT-29 cells using TRIzol reagent and following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was quantified with a Quant-iT RNA BR assay kit and Qubit fluorometer. For synthesis of cDNA, 2 µg of RNA was treated for 15 min at 20°C with 2 units of DNase I (RNase-free) in a volume of 10 μL, to remove contaminating DNA, followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme at 65°C for 10 min with 1 µL of 25 mM EDTA. Treated RNA was annealed with 1 µL random nonamers with 1 µL dNTP (10 mM) and 1 µL of water and heated at 65°C for 5 min and 1 min at 2°C in a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler. The cDNA was done with 1 µL of Superscript III reverse transcriptase, 1 µL of RNAseOUT, 1 µL of 0.1 M DTT, and 4 µL of 5X First-Strand Buffer, incubated in a PTC-200 Peltier Thermal cycler at 50°C for 60 min, and inactivated at 70°C for 15 min. For NTPDase mRNA evaluation, quantitative amplifications were done with 1 µL cDNA, 5 µL FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX), and 1 µL of specific primers (3 µM) in a MicroAMp optical 384-well reaction plate and using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system in 10 μL reaction volumes and the following program: (i) 2 min at 50°C, (ii) 10 min at 95°C, (iii) 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and (iv) a dissociation stage. For the standard curve, 10 copies to 108 copies of amplified fragment were used. For the negative controls, water was used as template. Each quantification was normalized with GAPDH. The primers used in this study for both RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primers.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2RY1 | AAAACTAGCCCCCTGCAACT | GATCTGATGCCGGATGAACT | 153 |

| P2RY2 | CCACCTGCCTTCTCACTAGC | TGGGAAATCTCAAGGACTGG | 163 |

| P2RY4 | GCAGGGATATCATGGGTGAC | CCCAGGAAGGAACAGAAACA | 109 |

| P2RY6 | AGCTGGGCATGGAGTTAAGA | GCTGACTGGGACCTCTCAAG | 139 |

| P2RY11 | CCTCTACGCCAGCTCCTATG | CCTCTACGCCAGCTCCTATG | 211 |

| P2RY12 | TTTGCCCGAATTCCTTACAC | ATTGGGGCACTTCAGCATAC | 192 |

| P2RY13 | CCCCTGGTACACTTGGAAGA | TACAGAGGAGGGGGTGATTG | 125 |

| P2RY14 | TCTTTGGGCTCATCAGCTTT | TCCGTCCCAGTTCACTTTTC | 213 |

| ENTPD1 | GCCAGCAGAAAAGGAGAATG | TGGGACCTTGGAATCACTTC | 159 |

| ENTPD2 | TCAATCCAGCTCCTTGAACC | TCCCCAGTACAGACCCAGAC | 167 |

| ENTPD3 | TTGACCTCAGGGCTCAGTTT | TGAGGGGGTTCACTGCTTAC | 159 |

| ENTPD8 | ACTGGGCTACATGCTGAACC | GCACCATGAACACCACTTTG | 107 |

| GAPDH | CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA | AGGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG | 228 |

| AK1 β a | GGAATTCGACCATGGGCTGCTGCTC | GGAATTCGCAGCAGTGTGGGCTGTC | 412 |

| AK1 β | ACAGGAGACACGGCAGGACGGGAC | CTCTTCTCCTTGCTGCACCTCC | 385 |

aTaken from reference [46].

2.7. Cell Transfection and Protein Preparation

HEK 293 cells were cultured and transfected in 10 cm plate using Lipofectamine as previously described [43]. Briefly, 80%–90% confluent cells were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) in the absence of fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 6 µg of plasmid DNA encoding for human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (GenBank accession no. NM_002526) previously described [49] and 24 µL of Lipofectamine reagent. The reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of DMEM containing 20% FBS and the cells were harvested 48 h later. For the preparation of protein extracts, transfected cells or HT-29 cells were washed three times with Tris-saline buffer at 4°C collected by scraping in the harvesting buffer (95 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 45 mM Tris at pH 7.5) and washed twice by 300 ×g centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in the harvesting buffer containing 10 µg/mL aprotinin and sonicated. Nucleus and cellular debris were discarded by centrifugation at 600 ×g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant (crude protein extract) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until used for experiments. Proteins concentrations were determined with a Quant-iT protein assay kit and Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies).

2.8. Immunoblotting and Antibodies

Protein extract was resolved on a NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris gel and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane by electroblotting according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore). The membrane was probed with the following antibodies: mouse anti-human NTPDase1 (BU61, Ancell Corporation (Bayport, MN, USA)), guinea pig anti-human NTPDase1 (hN1-1cI5), mouse monoclonal anti-human NTPDase2 (hN2-B2s and hN2-H9s), guinea pig anti-human NTPDase3 (hN3-1cI5), mouse monoclonal anti-human NTPDase3 (hN3-B3s), mouse anti-human NTPDase8 (hN8-6sI6), mouse monoclonal anti-human NTPDase8 (hN8-D7s), rabbit anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (h5′NT-2LI5), guinea pig anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (h5′NT-2cI5), and the mouse monoclonal anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (clone 4G4, Hycult Biotech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). All antibodies, except the mouse monoclonal anti-human NTPDase1 BU61 and the mouse anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase clone 4G4, were produced by cDNA immunization in our laboratory and their specificities were confirmed by immunoblots and immunohistochemistry [48, 50, 51]. These antibodies are available at http://ectonucleotidases-ab.com/. The secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies used were goat anti-mouse (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA), donkey anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Baie d'Urfe, Québec, Canada), and goat anti-guinea pig (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The blots were developed with the Western Lightning Plus-ECL reagent (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.9. Enzymatic Reactions

Enzyme activity was evaluated as described [43] in 0.2 mL of Tris-Ringer buffer (in mM: 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 5 D-glucose, and 80 Tris; pH 7.4) at 37°C. HT-29 lysates were added to the incubation mixture and preincubated at 37°C for 3 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 500 µM ATP, ADP, or AMP and stopped after 10–15 min with 50 µL of malachite green reagent. The activity at the cell surface was measured with confluent HT-29 cells in 24-well plates (about 200,000 cells per well). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12) supplemented with 10% FBS until conducting the activity assay that was performed in the buffer indicated above. The reactions were initiated as above and stopped by transferring an aliquot of the reaction mixture to a tube containing the malachite green reagent. Net cell-bound enzyme activity was calculated after subtracting the value measured in the control cell reaction mixture where the substrate was added after the malachite green reagent. Released inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured at 630 nm according to Baykov et al. [52]. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

One unit of enzymatic activity corresponds to the release of 1 μmol Pi/(min·mg of protein) or 1 μmol Pi/min/well at 37°C for protein extracts and intact cells, respectively.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed Student's t-test was performed using the Microsoft 2007 Excel software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. HT-29 Cells Express Purine-Metabolizing Ectoenzymes

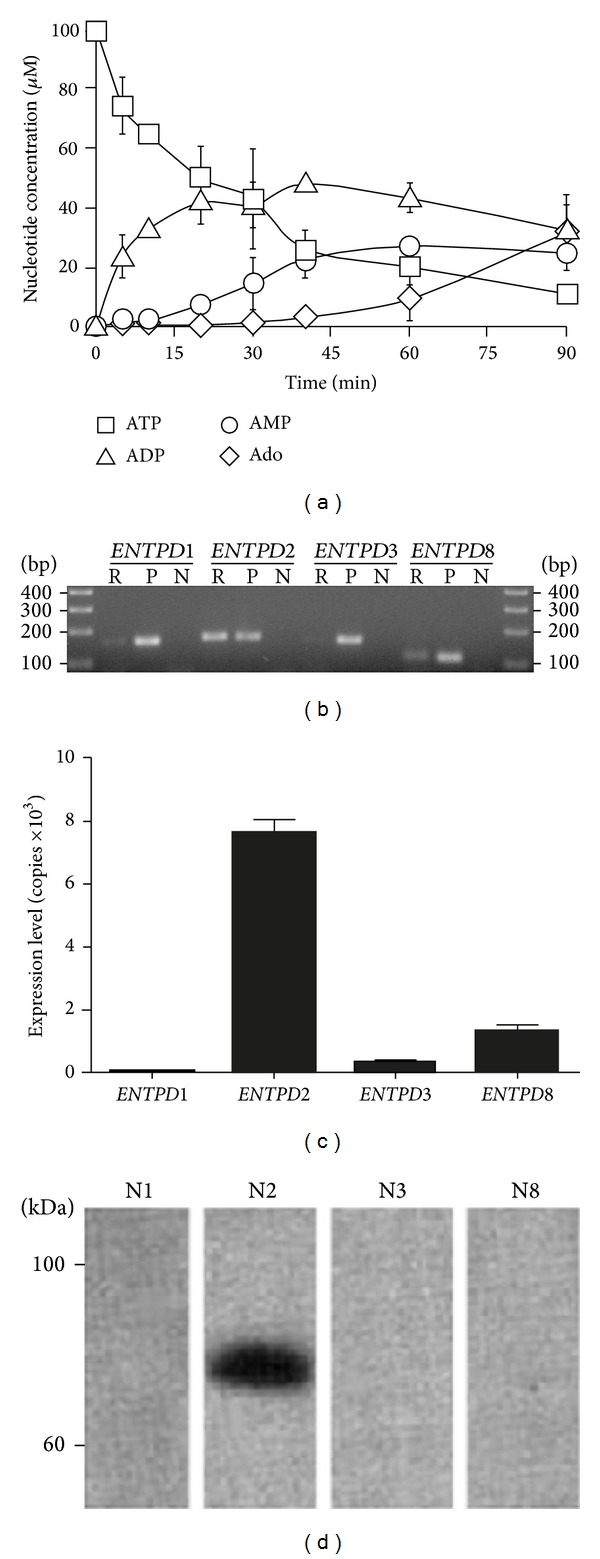

Our initial goal was to define the ectonucleotidases expressed in HT-29 cells. This was first done by investigating the metabolism of extracellular ATP and ADP by these cells. The analysis of ATP hydrolysis products showed a significant accumulation of ADP (Figure 1(a)), which fits the profile expected for NTPDase2 activity [43]. In agreement, semiquantitative PCR using primers specific to human NTPDase members expressed at the plasma membrane, namely, NTPDase1, -2, -3, and -8, showed high expression of NTPDase2 in HT-29 cells (Figure 1(b)). This was further confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 1(c)). Immunoblotting experiments using 2 different sets of antibodies to human NTPDase1, -2, -3, and -8 with protein samples extracted from HT-29 cells were consistent with the PCR results and confirmed the predominant presence of NTPDase2 in these cells (Figure 1(d) for one set of antibody and data not shown for the guinea pig anti-human NTPDase1 (hN1-1cI5), mouse monoclonal NTPDase2 (hN2-H9s), mouse monoclonal NTPDase3 (hN3-B3s), and mouse monoclonal NTPDase8 (hN8-D7s) antibodies; see Section 2).

Figure 1.

NTPDase2 is expressed by HT-29 cells. (a) HT-29 cells were incubated with ATP for 90 min and their supernatants were then subjected to RP-HPLC to quantify the various ATP degradation products (n = 3). (b) The expression of various human NTPDase genes was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR where R, P, and N represent the reaction with HT-29 cells, the positive controls, and the negative controls, respectively, and (c) by quantitative RT-PCR (n = 5). (d) The expression of NTPDase proteins in HT-29 cells was analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies to human NTPDase1, -2, -3, and -8, N1, N2, N3, and N8, respectively. A representative experiment of n = 4 is shown.

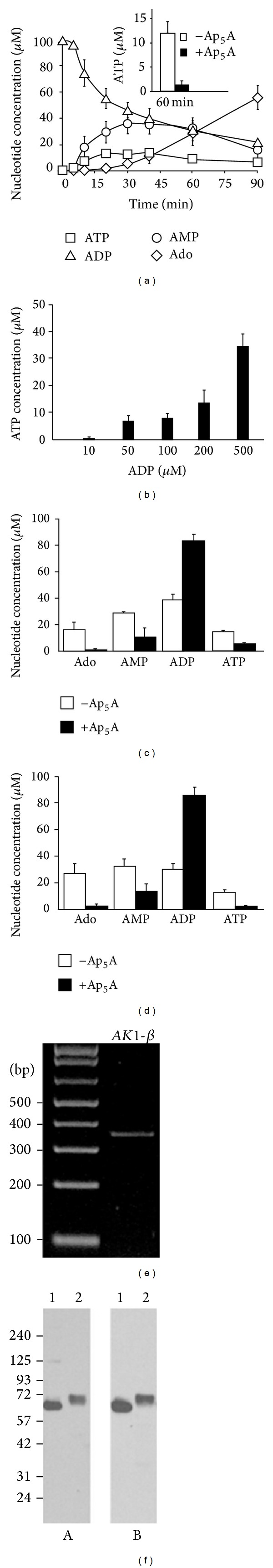

RP-HPLC analyses further revealed that HT-29 cells have the ability to produce ATP when incubated with ADP (Figure 2(a)). This implied the presence of an adenylate kinase (ADK) activity, which catalyzes the reversible reaction: 2ADP ⇌ ATP + AMP. The amount of ATP produced varied according to ADP concentration (Figure 2(b)). To confirm that this activity belonged to ecto-ADK, we tested whether Ap5A, a specific inhibitor of this enzyme, might affect ATP production. As shown in the inset of Figure 2(a), the production of ATP from ADP was inhibited by Ap5A. Semiquantitative RT-PCR using a published set of primers [46] (data not shown) as well as a home-made set designed from EST clone 781374 (NCBI accession number: AA430294; cf. Table 1), together with the subsequent sequencing of the amplicons, showed that HT-29 cells express AK1 β , which encodes the plasma membrane-localized isoform of ADK (Figure 2(e)).

Figure 2.

Adenylate kinase and ecto-5′-nucleotidase are expressed by HT-29 cells. (a) HT-29 cells were incubated with ADP for 90 min and their supernatants were subjected to RP-HPLC for the determination of purines and ADK activity (n = 3). Inset shows the effect of the ADK inhibitor, Ap5A, on ATP production by HT-29 cells after 1 h (n = 3). (b) Supernatants from HT-29 cells incubated for 30 min with various concentrations of ADP were subjected to RP-HPLC to determine ATP production (n = 3). ((c), (d)) Supernatants from HT-29 cells incubated for 30 min with either 100 µM ATP ((c) n = 2) or ADP ((d) n = 3), in the presence of 10 µM Ap5A or control vehicle, were subjected to RP-HPLC for the determination of adenine nucleotide and adenosine byproducts. (e) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis on HT-29 cell line showing the presence of the membrane associated adenylate kinase. A representative experiment of n = 2 is presented. (f) The expression of ecto-5′-nucleotidase protein was detected by immunoblotting with the rabbit anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase h5′NT-2LI5 ((A) on the left side) and with the commercial antibody clone 4G4 ((B) on right side). For panels (A) and (B), lane 1 represents the positive control of protein extract (6 µg) from HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with a human ecto-5′-Nucleotidase expression vector and lane 2 protein extract (20 µg) from HT-29.

Interestingly, the presence of ADK activity at the surface of HT-29 cells allowed adenosine production in the presence of either ATP (hydrolyzed to ADP by NTPDase2) or ADP. Indeed, adenosine production was prevented by the ADK inhibitor Ap5A (Figures 2(c) and 2(d)). As ATP and ADP, adenosine is of important biological value due to the various functions affected by this P1 receptor ligand. The production of adenosine cannot be explained by neither NTPDase2 nor ADK alone. Therefore the data presented in Figures 1(a), 2(a), 2(c), and 2(d) suggested the presence of ecto-5′-nucleotidase which was confirmed by 3 different antibodies that showed the same immunoreactive band (Figure 2(f); data not shown for the guinea pig anti-human ecto-5′-nucleotidase antibody; see Section 2). Finally, the hydrolysis of ATP, ADP, and AMP was also evaluated at the surface of HT-29 cells as well as with protein extracts which confirmed the presence of enzymes able to hydrolyze ATP and AMP as substrate (Table 2), in agreement with the presence of NTPDase2 and ecto-5′-nucleotidase.

Table 2.

Adenine nucleotide hydrolysis at the surface of HT-29 cells and protein extracts.

| Activities | Intact cells (n = 4) [nmoles Pi ·min−1 ·well−1] |

Cell lysates (n = 3) [nmoles Pi ·min−1 ·mg prot−1] |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 115 ± 4 |

| ADPase | 1.5 ± 0.01 | 38 ± 1 |

| AMPase | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 67 ± 3 |

The hydrolysis of ATP, ADP, and AMP as substrate was performed and the liberated Pi was determined by the malachite green assay as detailed in Section 2.

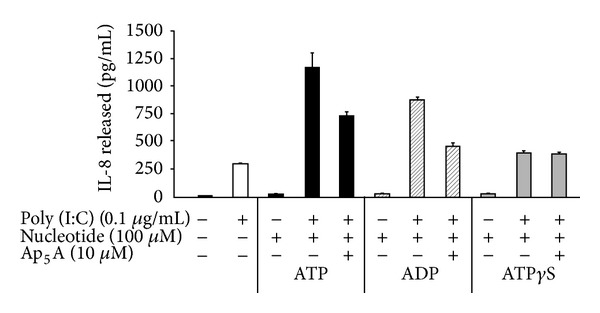

3.2. NTPDase2 and ADK Affect IL-8 Production

We then addressed the hypothesis that the purine-metabolizing enzymes expressed at the surface of HT-29 cells can affect the release of IL-8. As ATP and ADP alone did not activate IL-8 release, these assays were performed in the presence of a suboptimal concentration of poly (I:C) which is a TLR3 agonist. TLR3 activation was selected for the following reasons. TLR3 activation stimulates IL-8 release in HT-29 cells [32] in a nucleotide dependent manner (manuscript in preparation). In addition, TLR3 was found to be involved in different cancers [53, 54] and was also reported to affect intestinal inflammation in a complex manner depending on the conditions, either protecting from inflammation or causing epithelial destruction [55–59].

In agreement with a role of ADK in IL-8 release by ATP- or ADP-stimulated HT-29 cells, Ap5A significantly diminished IL-8 release induced by either nucleotide (Figure 3). As expected, Ap5A did not affect IL-8 release triggered by ATP-γ-S (Figure 3), a nonhydrolysable ATP analogue, suggesting that the reduction in ATP-induced IL-8 secretion seen in the presence of the ADK inhibitor was due to the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP catalyzed by NTPDase2. This experiment also confirmed that the effect of Ap5A on IL-8 release was specific to ADK inhibition as Ap5A did not affect the poor induction of IL-8 release by ATP-γ-S. In this system, adenosine did not affect IL-8 release when HT-29 cells were stimulated with the TLR3 agonist poly (I:C) (data not shown), suggesting that, in these conditions with this cell line, ecto-5′-nucleotidase did not affect IL-8 production and release.

Figure 3.

NTPDase2 and ADK modulate IL-8 production in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were stimulated for 18 h with suboptimal concentration of poly (I:C) in combination with ATP, ADP, or the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, ATP-γ-S, in the presence or absence of the ADK inhibitor, Ap5A. The cell supernatants were then analyzed for IL-8 by ELISA (n = 3).

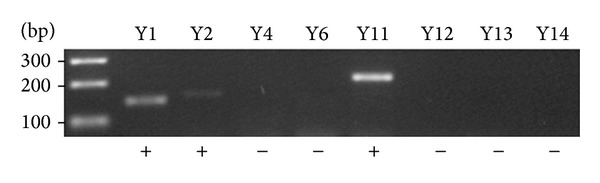

3.3. HT-29 Cells Express P2Y Receptors

We then analyzed the repertoire of P2Y receptors expressed in HT-29 cells by semiquantitative PCR. As seen in Figure 4, HT-29 cells express P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y11. No, or very little, mRNA expression could be detected for the other P2Y receptors.

Figure 4.

Comparative expression of human P2Y receptors in HT-29 cells by semiquantitative RT-PCR. A representative experiment of n = 2 is shown. Presence (+) of P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y11 was detected while the other P2Y receptors were not detected (−).

4. Discussion

The production of IL-8 by HT-29 cells was affected by two ectoenzymes present at the surface of these cells, namely, ADK and NTPDase2. ADK activity increased the effects of exogenous ATP and ADP on IL-8 release in cells stimulated with a low concentration of poly (I:C). Indeed, the inhibition of ADK by Ap5A decreased IL-8 release promoted by these nucleotides. The Ap5A-dependent inhibition of IL-8 production triggered by exogenous ATP also suggests an involvement of NTPDase2, which provides a substrate for ADK through the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP. In contrast to NTPDase2, one might expect that such a significant potentiation of IL-8 release would not be possible if ADK was coupled with either NTPDase1, -3, or -8 which hydrolyze ADP and would therefore compete with ADK for this substrate. In agreement with the role of ADK in HT-29 cells, this enzyme present in lung epithelial cells also transiently maintains the increased concentration of ATP that can favor the activation of P2 receptors specific for that nucleotide [60]. ADK also promotes lymphocyte transendothelial migration by maintaining a significant level of ATP near the surface of these cells (halo ATP) [61].

We also observed that the ADK and NTPDase2 pair expressed in HT-29 cells makes the production of adenosine possible. Indeed, while NTPDase2 is required for ADP production from ATP, ADK converts two molecules of ADP to ATP and AMP. The latter is the substrate of ecto-5′-nucleotidase that converts it to adenosine which was detected in the cell supernatant of HT-29 cells (Figures 2(a), 2(c), and 2(d)). Adenosine production is of great physiological importance due to the large variety of functions played by the activation of P1 receptors in all tissues and cells, which includes key functions in the regulation of inflammation [62, 63].

Surprisingly, the presence of adenosine made possible by ADK and ecto-5′-nucleotidase did not affect IL-8 release in our conditions. We first anticipated that adenosine would affect IL-8 production in HT-29 cells. Indeed, in conditions of inflammation induced by TNF-α, the activation of the adenosine receptor A3 was previously shown to inhibit IL-8 expression through the inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathways [37]. It is noteworthy that the secretion of IL-8 by adenosine appears to depend on experimental conditions in HT-29 cells as the adenosine receptor agonist NECA was also reported to induce a small IL-8 release under severe hypoxia via A2B [38]. Nevertheless, while we found that NTPDase2 and ADK ectoenzymes could affect IL-8 release, our data also suggest that in other conditions, IL-8 secretion could also be potentially affected by the presence of ecto-5′-nucleotidase. In addition, as IL-8 is also produced by other epithelial cells in an ATP dependent fashion [64], such a regulation of nucleotide signaling by ectoenzymes is also possible in other cells.

Importantly, the presence of adenosine made possible by the presence of ADK and ecto-5′-nucleotidase could affect other functions in HT-29 cells. For example, adenosine increases HT-29 cells proliferation [39] via the activation of A3 receptor [36, 42]. The A3 receptor was the most expressed adenosine receptor in human colon cancer tissues and in colon cell lines such as HT-29 cells [42]. Interestingly caffeine, a P1 receptor antagonist, has been associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer in a number of case-control studies [38] which suggest an important role of adenosine and of ecto-5′-nucleotidase in colorectal cancer development.

5. Conclusions

HT-29 cells regulate adenine nucleotide levels by the combined action of NTPDase2, ADK, and ecto-5′-nucleotidase. This combination of ectoenzymes allows the generation of adenosine from secreted ATP while keeping ATP level high for a longer period of time. This also permits a sustained P2 receptor activation leading to IL-8 secretion which would normally be stopped rapidly by NTPDase2 if ADK was absent. These mechanisms of regulation of IL-8 release observed in this human cancer intestinal epithelial cell line might well play an important role in tumor progression as well as in the pathology of IBD and other related inflammatory disorders. If also present in primary cells, the underlining mechanism of IL-8 production identified in this work presents a new pathway that may be targeted in some of these associated diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants to J. Sévigny from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; MOP-93683). F. Bahrami was a recipient of a fellowship from the CIHR/Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and J. Sévigny of a “Chercheur National” award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS). The authors thank Dr. Richard Poulin (Scientific Proofreading and Writing Service, CHUQ Research Center) for editing a preliminary version of this paper.

Conflict of Interests

The authors state no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1907–1913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annual Review of Immunology. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Platz EA, et al. Pathological and molecular mechanisms of prostate carcinogenesis: implications for diagnosis, detection, prevention, and treatment. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2004;91(3):459–477. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1099–1105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Triantafillidis JK, Nasioulas G, Kosmidis PA. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies. Anticancer Research. 2009;29(7):2727–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. The Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1603–1613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsushima K, Morishita K, Yoshimura T, et al. Molecular cloning of a human monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor (MDNCF) and the induction of MDNCF mRNA by interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1988;167(6):1883–1893. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeilhofer HU, Schorr W. Role of interleukin-8 in neutrophil signaling. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2000;7(3):178–182. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzucchelli L, Hauser C, Zgraggen K, et al. Expression of interleukin-8 gene in inflammatory bowel disease is related to the histological grade of active inflammation. The American Journal of Pathology. 1994;144(5):997–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimm MC, Elsbury SKO, Pavli P, Doe WF. Interleukin 8: cells of origin in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1996;38(1):90–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell LM, Maxwell PJ, Waugh DJJ. Rationale and means to target pro-inflammatory interleukin-8 (CXCL8) signaling in cancer. Pharmaceuticals. 2013;6(8):929–959. doi: 10.3390/ph6080929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Iglesia N, Konopka G, Lim K, et al. Deregulation of a STAT3-interleukin 8 signaling pathway promotes human glioblastoma cell proliferation and invasiveness. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(23):5870–5878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5385-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarogoulidis P, Katsikogianni F, Tsiouda T, Sakkas A, Katsikogiannis N, Zarogoulidis K. Interleukin-8 and interleukin-17 for cancer. Cancer Investigation. 2014;32(5):197–205. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2014.898156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukulski F, Yebdri FB, Lefebvre J, Warny M, Tessier PA, Sévigny J. Extracellular nucleotides mediate LPS-induced neutrophil migration in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2007;81(5):1269–1275. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kukulski F, Ben Yebdri F, Lecka J, et al. Extracellular ATP and P2 receptors are required for IL-8 to induce neutrophil migration. Cytokine. 2009;46(2):166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yebdri FB, Kukulski F, Tremblay A, Sévigny J. Concomitant activation of P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors on monocytes is required for TLR1/2-induced neutrophil migration by regulating IL-8 secretion. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39(10):2885–2894. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Virgilio F. Purinergic mechanism in the immune system: a signal of danger for dendritic cells. Purinergic Signalling. 2005;1(3):205–209. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6312-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a “danger signal”. Science Signaling. 2009;2(56, article pe6) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen GY, Nuñez G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2010;10(12):826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bours MJL, Swennen ELR, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;112(2):358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Sévigny J. Impact of ectoenzymes on P2 and P1 receptor signaling. Advances in Pharmacology. 2011;61:263–299. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robson SC, Sévigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2(2):409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaudoin AR, Sévigny J, Picher M. ATP-diphosphohydrolases, apyrases, and nucleotide phosphohydrolases: biochemical properties and functions. In: Lee AG, editor. ATPases. Greenwich, UK: JAI Press; 1996. pp. 369–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signalling. 2012;8(3):437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Q, Inouye M. Adenylate kinase complements nucleoside diphosphate kinase deficiency in nucleotide metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(12):5720–5725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James S, Richardson PJ. Production of adenosine from extracellular ATP at the striatal cholinergic synapse. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;60(1):219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb05841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular Cell Research. 2008;1783(5):673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abreu-Martin MT, Vidrich A, Lynch DH, Targan SR. Divergent induction of apoptosis and IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells in response to TNF-α and ligation of Fas antigen. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(9):4147–4154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly CP, Keates S, Siegenberg D, Linevsky JK, Pothoulakis C, Brady HR. IL-8 secretion and neutrophil activation by HT-29 colonic epithelial cells. The American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267(6):G991–G997. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.6.G991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneeman TA, Bruno MEC, Schjerven H, Johansen F, Chady L, Kaetzel CS. Regulation of the polymeric Ig receptor by signaling through TLRs 3 and 4: linking innate and adaptive immune responses. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(1):376–384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Höpfner M, Lemmer K, Jansen A, et al. Expression of functional P2-purinergic receptors in primary cultures of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;251(3):811–817. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Höpfner M, Maaser K, Barthel B, et al. Growth inhibition and apoptosis induced by P2Y2 receptors in human colorectal carcinoma cells: involvement of intracellular calcium and cyclic adenosine monophosphate. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2001;16(3):154–166. doi: 10.1007/s003840100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu H, O'Mullane LM, Cummins MM, et al. Negative regulation of Ca2+ influx during P2Y2 purinergic receptor activation is mediated by Gβγ-subunits. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakowicz-Burkiewicz M, Kitowska A, Grden M, Maciejewska I, Szutowicz A, Pawelczyk T. Differential effect of adenosine receptors on growth of human colon cancer HCT 116 and HT-29 cell lines. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2013;533(1-2):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren T, Qiu Y, Wu W. Activation of adenosine A3 receptor alleviates TNF-α-induced inflammation through inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway in human colonic epithelial cells. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2014/818251.818251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, et al. Caffeine inhibits adenosine-induced accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and interleukin-8 expression in hypoxic human colon cancer cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007;72(2):395–406. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.032920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lelièvre V, Muller J, Falcòn J. Adenosine modulates cell proliferation in human colonic carcinoma. II. Differential behavior of HT29, DLD-1, Caco-2 and SW403 cell lines. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;341(2-3):299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lelièvre V, Caigneaux E, Muller J, Falcón J. Extracellular adenosine deprivation induces epithelial differentiation of HT29 cells: Evidence for a concomitant adenosine A1/A2 receptor balance regulation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;391(1-2):21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linden J. Adenosine metabolism and cancer. Focus on “Adenosine downregulates DPPIV on HT-29 colon cancer cells by stimulating protein tyrosine phosphatases and reducing ERK1/2 activity via a novel pathway”. The American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2006;291(3):C405–C406. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00242.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K, et al. Adenosine receptors in colon carcinoma tissues and colon tumoral cell lines: focus on the A3 adenosine subtype. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;211(3):826–836. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Lavoie ÉG, et al. Comparative hydrolysis of P2 receptor agonists by NTPDases 1, 2, 3 and 8. Purinergic Signalling. 2005;1(2):193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2(2):351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sträter N. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase: structure function relationships. Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2(2):343–350. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collavin L, Lazarevič D, Utrera R, Marzinotto S, Monte M, Schneider C. wt p53 dependent expression of a membrane-associated isoform of adenylate kinase. Oncogene. 1999;18(43):5879–5888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wirth M, Berthold E, Grashoff M, Pfutzner H, Schubert U, Hauser H. Detection of mycoplasma contaminations by the polymerase chain reaction. Cytotechnology. 1994;16(2):67–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00754609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelletier J, Lavoie EG, Fausther M, et al. Production d’anticorps contre les NTPDases. 9e journée scientifique du CRRI. Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations, Wendake, Canada, Cahier des résumés, p. 31, 2010.

- 49.Lecka J, Rana MS, Sévigny J. Inhibition of vascular ectonucleotidase activities by the pro-drugs ticlopidine and clopidogrel favours platelet aggregation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;161(5):1150–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, Yu L, Wang Q, et al. Expression of ecto-ATPase NTPDase2 in human dental pulp. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91(3):261–267. doi: 10.1177/0022034511431582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munkonda MN, Pelletier J, Ivanenkov VV, et al. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody as the first specific inhibitor of human NTP diphosphohydrolase-3: partial characterization of the inhibitory epitope and potential applications. FEBS Journal. 2009;276(2):479–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baykov AA, Evtushenko OA, Avaeva SM. A malachite green procedure for orthophosphate determination and its use in alkaline phosphatase-based enzyme immunoassay. Analytical Biochemistry. 1988;171(2):266–270. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaz J, Andersson R. Intervention on toll-like receptors in pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(19):5808–5817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandez-Garcia B, Eiró N, González-Reyes S, et al. Clinical significance of toll-like receptor 3, 4, and 9 in gastric cancer. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2014;37(2):77–83. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118(2):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strober W. Epithelial cells pay a Toll for protection. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(9):898–900. doi: 10.1038/nm0904-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vijay-Kumar M, Wu H, Aitken J, et al. Activation of toll-like receptor 3 protects against DSS-induced acute colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2007;13(7):856–864. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou R, Wei H, Sun R, Zhang J, Tian Z. NKG2D recognition mediates Toll-like receptor 3 signaling-induced breakdown of epithelial homeostasis in the small intestines of mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(18):7512–7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700822104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ostvik AE, Granlund A, Gustafsson BI, et al. Mucosal toll-like receptor 3-dependent synthesis of complement factor B and systemic complement activation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2014;20(6):995–1003. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picher M, Boucher RC. Human airway ecto-adenylate kinase: a mechanism to propagate ATP signaling on airway surfaces. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(13):11256–11264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henttinen T, Jalkanen S, Yegutkin GG. Adherent leukocytes prevent adenosine formation and impair endothelial barrier function by Ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73-dependent mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(27):24888–24895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Linden J. Adenosine in tissue protection and tissue regeneration. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;67(5):1385–1387. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abbracchio MP, Ceruti S. P1 receptors and cytokine secretion. Purinergic Signalling. 2007;3(1-2):13–25. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kruse R, Demirel I, Säve S, Persson K. IL-8 and global gene expression analysis define a key role of ATP in renal epithelial cell responses induced by uropathogenic bacteria. Purinergic Signal. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]