Abstract

2-Arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba adenosine 5′-methyluronamides containing rigid N6-(trans-2-phenylcyclopropyl) and 2-phenylethynyl groups were synthesized as agonists for probing structural features of the A3 adenosine receptor (AR). Radioligand binding confirmed A3AR selectivity and N6-1S,2R stereoselectivity for one diastereomeric pair. The environment of receptor-bound, conformationally constrained N6 groups was explored by docking to an A3AR homology model, indicating specific hydrophobic interactions with the second extracellular loop able to modulate the affinity profile. 2-Pyridylethynyl derivative 18 was administered orally in mice to reduce chronic neuropathic pain in the chronic constriction injury model.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, purines, molecular modeling, structure activity relationship, radioligand binding, adenylate cyclase

X-ray crystallographic structures of the A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR) in complex with both agonists and antagonists1–3 can serve as suitable templates for accurately predicting the ligand interactions of other AR subtypes. We now focus on sterically bulky and hydrophobic N6 substituents on adenosine derivatives that are associated with high affinity at the A3AR. Adenosine derivatives that selectively activate the A3AR are in clinical trials for autoimmune inflammatory diseases and liver cancer; thus, there is considerable interest in drug discovery at this receptor.4

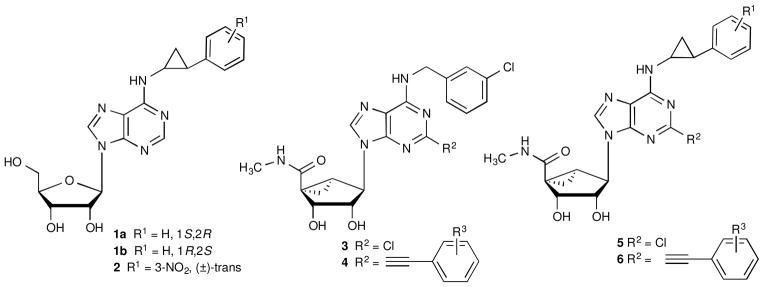

Many studies have established the effects of diverse substitution of the exocyclic amine of adenosine on the AR subtype selectivity, with predominantly hydrophobic N6 groups found to be best suited for high affinity.5–7 For example, the structure activity relationship (SAR) of the N6-(2-trans-phenylcyclopropyl) group and its substituted analogues was studied in monosubstituted adenosine derivatives (e.g. 1, 2, Chart 1), which tended toward selectivity at the A3AR.8 The steric constraint and stereochemical definition of the N6-(2-trans-phenylcyclopropyl) group, especially in combination with rigid ribose substitutions, make it possible to study the structural implications of this conformationally constrained substituent in A3AR recognition. Here we use a recent homology model9 of the human (h) A3AR to probe the structural basis for the effects on binding affinity in this class of agonists.

We previously explored a class of constrained (N)-methanocarba adenosine-5′-methylamide nucleosides, including 2-chloro derivatives (e.g. 3)10 and C2-arylethynyl analogues (e.g. 4),9,12 that are very potent and selective full agonists of the A3AR. N6-Benzyl-type substitution is often used because of its selective enhancement of A3AR affinity. Here, we have synthesized new N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl)-substituted analogues in this extended methanocarba series and characterized them pharmacologically. We already reported the A3AR selectivity of one analogue, 5 (R1=H) in which a rigid ribose-like (N)-methanocarba scaffold10 was combined with a sterically restricted N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) substitution, based on our earlier study of SAR in the 9-riboside series.8 The corresponding 4′-truncated (N)-methanocarba nucleoside containing a racemic N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) substitution was found to be a selective A3AR antagonist (Ki 1.3 nM).13 The 1S,2R diastereoisomer of 2 was ~10-fold more potent in binding to the hA3AR (Ki 11.2 nM) than the corresponding 1R,2S isomer. This N6 substituent was also combined with C2-cyano or carboxamide substitution in a subsequent 9-riboside series resulting in a moderate reduction of A3AR affinity.14 In our earlier study of ribosides,8 there was a 38-fold stereoselectivity of 1a vs. 1b in A3AR binding, and a smaller ratio was observed for stereoisomers of a 3-nitro derivative 2. A large species difference was associated with the N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group, such that affinity was greatly enhanced in progressing from rat to human.

The current expanded series (general formula 6) combined rigid C2-arylethynyl and N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) groups. This extended, sterically defined N6 substitution allows for the exploration of the outer regions of the A3AR by docking of the ligands to homology models of the receptor. Thus, the effects of the interaction of different N6 substituents with the normally flexible extracellular loops (ELs) were analyzed by detailed modeling.

Chronic neuropathic pain (NP) is an important unsolved medical need, which is associated with nerve injury and often with diseases such as cancer and diabetes.15,16 We recently reported that A3AR agonists have unanticipated efficacy in vivo in various models of chronic but not acute pain.1 Although N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) substitution in the riboside series greatly reduces the affinity at the murine A3ARs,24 we studied one of the new analogues in a mouse model of chronic pain resulting from constriction injury (CCI).17

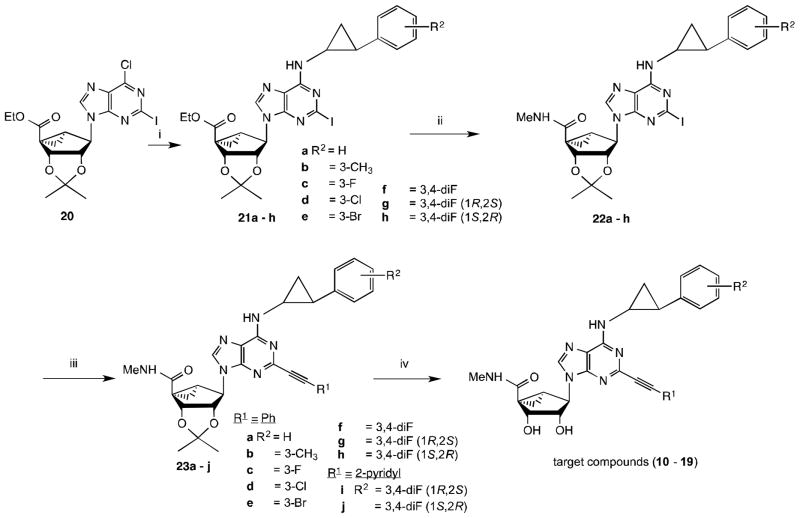

The nucleoside derivatives 9–19 (Table 1) were synthesized, characterized and examined in AR binding assays. Compounds 1, 4, 5, 7 and 8, prepared earlier,8–10,12 were included as reference compounds. To synthesize N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) derivatives, protected intermediate 209 was sequentially treated with the appropriate 2-phenylcyclopropylamine to yield 21a–h followed by methylamine to provide 22a–h (Scheme 1). Then, intermediates 22a–h were subjected to Sonogashira coupling with the appropriate arylacetylene in the presence of PdCl2(Ph3P)2, CuI and triethylamine to give protected intermediates 23a–j, which upon acid hydrolysis gave the target compounds 10–19. The synthesis of 6-NH2 derivative 9 will be reported elsewhere. Although most of the entries in Table 1 contain a mixture of stereoisomers, compounds 16–19 correspond to products with well-defined (1R,2S or 1S,2R) stereochemistry of the N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group. Compound 15 is the racemic form of pure diastereoisomers 16 and 17.

Table 1.

Structures and binding affinities of reference nucleosides and newly synthesized (N)-methanocarba A3AR agonists (9–19).

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | X | R2 or R4 | Configuration of N6 group | A1ARa % inhibition or Ki (nM) | A2AARa % inhibition or Ki (nM) | A3ARa,c Ki (nM) |

| 1b,d | e | e | (±)-trans | 124 ± 30 nM | 2530 ± 720 nM | 0.86 ± 0.09 |

| 4b | e | 3-Cl-PhCH2 | e | 20 ± 3% | 27 ± 3% | 1.34 ± 0.30 |

| 5b,d (R1=H) | e | e | (±)-trans | 770 ± 50 nM | 4800 ± 200 nM | 0.78 ± 0.06 |

| 7b | e | Ph-(CH2)2 | e | 11 ± 3% | 32 ± 4% | 1.23 ± 0.57, |

| 8b | e | CH3 | e | 13 ± 6% | 14 ± 7% | 0.85 ± 0.22 |

| 9 | e | H | e | 28 ± 4% | 1200 nM | 1.51 ± 0.41 |

| 10 | CH | H | (±)-trans | 2 ± 1% | 43 ± 8% | 6.16 ± 0.22 |

| 11 | CH | 3-CH3 | (±)-trans | 8 ± 4% | 53 ± 6% | 17.6 ± 1.3 |

| 12 | CH | 3-F | (±)-trans | 18 ± 10% | 0 ± 0% | 16.5 ± 1.9 |

| 13 | CH | 3-Cl | (±)-trans | 6 ± 3% | 39 ± 5% | 11.2 ± 4.2 |

| 14 | CH | 3-Br | (±)-trans | 17 ± 4% | 32 ± 18% | 14.5 ± 1.0 |

| 15 | CH | 3,4-diF | (±)-trans | 11 ± 6% | 6 ± 3% | 20.2 ± 2.1 |

| 16f | CH | 3,4-diF | 1R, 2S-trans | 11 ± 6% | 0 ± 0% | 16.9 ± 3.3 |

| 17f | CH | 3,4-diF | 1S, 2R-trans | 16 ± 1% | 0 ± 0% | 4.55 ± 1.63 |

| 18 | N | 3,4-diF | 1R, 2S-trans | 19 ± 8% | 25 ± 5% | 8.18 ± 2.22 |

| 19 | N | 3,4-diF | 1S, 2R-trans | 26 ± 1% | 41 ± 1% | 7.31 ± 1.74 |

Binding was performed as described12 using membranes prepared from HEK293 (A2A only) or CHO cells stably expressing one of three hAR subtypes. The binding affinities for A1, A2A and A3ARs were determined using agonist radioligands [3H]N6-R-phenylisopropyladenosine ([3H]24), [3H]2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine ([3H]25), or [125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide ([125I]26), respectively. Data (n = 3-4) are expressed as Ki values. A percent in italics refers to inhibition of binding at 10 μM. Stock solutions of N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) derivatives in DMSO were stored at −80 °C.

Human, unless noted as mouse (m) or rat (r).8 mA3AR binding was determined in membranes prepared from stably transfected HEK293 cells using [125I]26, as described.12

See Chart 1 for structure.

Not applicable.

16, MRS7030; 17, MRS7034.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of N6-phenylcyclopropyl (N)-methanocarba derivatives 10–19.

Reagents: (i) R2-phenylcyclopropyl-H2, Et3N, MeOH, rt; (ii) 40% MeNH2, MeOH, rt; (iii) HC≡CR1, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, Et3N, DMF, rt; (iv) 10% TFA, MeOH, 70°C.

The binding assays were based on widely used radioligands using membranes of CHO cells expressing the hA1AR ([3H]24) or hA3AR ([125I]26) or HEK293 cells expressing the hA2AAR ([3H]25).18–20 Most of the nucleosides bound to the hA3AR with low nanomolar affinity and with minimal binding to the hA1AR and hA2AAR. Although the A3AR affinity range of the newly synthesized 2-arylethynyl compounds was somewhat less than the reference 2-chloro- (N)-methanocarba nucleoside 5, the selectivity remained high, with the significant reduction in affinity at the A1 and A2AARs. The unsubstituted, racemic N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) derivative 10 retained a higher A3AR affinity than the ring-substituted analogues 11–15. However, the 3,4-difluorophenyl analogue 15 was very selective for the A3AR, and the fluoro substitution was intended to diminish aromatic oxidation in vivo.26 A comparison of the A3AR affinity of diastereomeric pairs showed a 4-fold preference for the 1S,2R diastereoisomer in the pair of 2-phenylethynyl derivatives 16 and 17, but there was no difference in A3AR affinities of the 2-(2-pyridylethynyl) diastereomeric pair 18 and 19.

Therefore, we have used a combination of adenine substitutions and a ribose-like scaffold, all of greatly reduced conformational freedom, to help analyzing ligand recognition in the outer regions of the A3AR. The environment of receptor-bound N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group was explored by docking to an A3AR homology model. We used our previously-reported homology model of the hA3AR,9,12 which was based on a hybrid A2AAR-β2 adrenergic receptor template. The general methodology used for homology modeling (MOE homology modeling tool)21 and ligand docking (Glide module of the Schrödinger Suite)18 has been described before,9,12 and specific methodological details are reported in the Supporting Information. In the present study, after the first round of docking to the initial A3AR homology model and selection of the best docking pose for derivative 7, we performed refinement of the portion of the second EL in contact with the ligand (from Gln167 to Arg173), using the Prime module of the Schrödinger Suite,22 to optimize its conformation around the N6 substituent. This step was followed by a second round of docking of all derivatives to the optimized model, to identify the final proposed docking poses. All of the final nucleosides were subjected to docking simulations at a hA2AAR crystal structure (PDB ID: 2YDV)3 to explore the reasons for ligand selectivity.

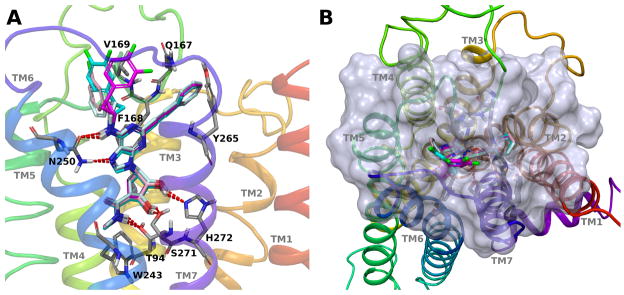

As expected, docking results at the hA3AR for all the analyzed derivatives showed the pseudo-sugar moiety, adenine N7 and exocyclic NH participating in highly conserved H-bonding interactions with key residues of the binding site (Figure 1), such as Thr94 (3.36), Asn250 (6.55), Ser271 (7.42) and His272 (7.43) (numbers in parenthesis follow the Ballesteros-Weinstein notation).23 The same H-bonding network has been observed in the agonist-bound hA2AAR crystal structures and is supposed to be important for receptor activation.2,3 Another important binding feature for AR ligands, both agonists and antagonists, is the π-π stacking interaction with an aromatic residue in EL2 (Phe168 at the hA3AR). Thus, considering that our quite rigid compounds showed all these critical interactions when docked to the A3AR model, we could analyze in more detail the possible interactions with the less defined EL regions of the receptor. Docking results showed the rigid C2-arylethynyl substituent of the synthesized compounds to be directed towards the extracellular side in proximity of TM2; in fact, this group could be accommodated in the binding site only after outward movement of TM2, as previously described.9,12 On the other hand, the different N6 substituents of the reported derivatives are in proximity of EL2, and even though the recognition region for the N6 group is on the outer regions, it involves mainly hydrophobic residues at the hA3AR. In fact, at this receptor the exocyclic amino group of the ligands is in proximity of a small, secondary (side) pocket delimited by EL2 (residues Val169, Ser170, Val171, Met172, Arg173, Met174 and Met 151). This side pocket is able to well accommodate substituents such as N6-(3-Cl-benzyl) and N6-phenylethyl (see docking poses of corresponding compounds 4 and 7 in Figure 1). The good fit of these substituents with this region can explain the very high affinity of such compounds at the hA3AR. These two derivatives also showed high affinity for the mouse A3 subtype, in agreement with the observation that the mA3AR can accommodate these N6 substituents in the same region, as previously reported,12 even though the surrounding residues are different. One key difference is the presence of an Arg in the murine A3 subtypes (both mouse and rat) in place of Val169 in the hA3AR. This bulkier and positively charged residue can determine a more difficult fit of bulkier and/or more rigid N6 groups. This observation can explain the substantially lower affinity of compound 1, with the N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group, at the rA3AR as compared to the hA3AR.8

Figure 1.

Putative binding modes of selected (N)-methanocarba derivatives obtained after docking simulations at the hA3AR model. (A) Side view of the receptor binding site. Ligands are shown in sticks: compound 4 (pink carbons), compound 7 (pale cyan carbons), compound 16 (magenta carbons) and compound 17 (cyan carbons). Side chains of some amino acids important for ligand recognition are highlighted (grey carbon sticks). H-bonding interactions are pictured as dotted lines. Nonpolar hydrogen atoms are not displayed. (B) Top view of the receptor binding site. Semi-transparent surface of binding site’s residues is displayed. Color scheme as in panel A.

Residues in EL2 seem to be implicated also in A2A vs A3 selectivity, as suggested before by docking studies.24 At the hA2AAR, the glutamic acid (Glu169) present at this position interacts through H-bonds with both agonists (at unsubstituted 6-NH2 groups) and antagonists, as highlighted by crystallographic data.1–3 As we observed previously, the insertion of an extended C2-arylethynyl substituent considerably reduces the affinity at the A2A subtype.9 However, the only C2-arylethynyl derivative showing a good docking pose at the hA2AAR was compound 9 (Figure S1, Supporting Information), in agreement with its binding affinity of ~1 μM at this subtype. This compound is the only one of the series presenting an unsubstituted exocyclic amino group, which can interact with Glu169 in EL2 through a H-bond.

At the hA3AR, the N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group of the C2-arylethynyl compounds can still be accommodated in the region surrounded by EL2, even though there is a cost in affinity. This is probably due to the increased rigidity compared to the N6-phenylethyl derivatives (compare compound 10, Ki hA3AR = 6.16 nM, and compound 7, Ki hA3AR = 0.85 nM). Moreover, binding data from both the ribose series and (N)-methanocarba series showed binding stereoselectivity for this substituent in several isomeric pairs with preference for the 1S,2R diastereoisomer. This can be explained considering that the 1S,2R isomers could better fit the EL2-delimited side pocket as compared to the 1R,2S isomers, as shown by the docking poses of compounds 16 and 17 in Figure 1. On the other hand, no difference in affinity was observed for the N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) C2-(2-pyridylethynyl) isomers 18 and 19. This seems to be related to a compensatory effect due to the formation of an additional H-bond between the pyridine nitrogen and the backbone amino group of Phe168 in EL2 of the hA3AR (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

The importance of the ELs in ligand recognition is emphasized in the modeling results. In fact, even though compounds have the ability to form all the crucial interactions with key residues in the lower part of the binding site, N6 and C2 substituents can modulate their affinity by interacting with the aqueous-exposed outer region of the binding site. In general, the hA3AR is able to tolerate bulkier and/or more rigid substitutions at these positions as compared to the murine A3ARs and the hA2AAR, because of the differences present in EL2. Therefore, the hA3AR can accommodate several different-sized N6 groups, i.e. methyl, 3-Cl-benzyl, phenylethyl and 2-phenylcyclopropyl, in a hydrophobic region delimited by EL2, maintaining good affinity. Moreover, different N6- and C2-substituents seem to influence each other depending on their complementarity with the binding site. In fact, the presence of a N6-(2-phenylcyclopropyl) group is more tolerated in absence of an extended C2-arylethynyl, while the presence of both rigid groups makes it more difficult to accommodate the compound in the cavity (compare compound 5, Ki hA3AR = 0.78 nM, and compound 10, Ki hA3AR = 6.16 nM). The C2 substituent can also have a compensatory effect due to the formation of additional interactions as observed in the C2-(2-pyridylethynyl) series. The modulatory action of these two substituents can be related both to their ability to properly orient the ligand in the binding site so that it can form optimal interactions with key residues, and to their possible role in influencing the conformation of residues in EL2 by modulating their interaction with the ligand. This is understandable considering that a highly conserved interaction in AR binding is the adenine π-π stacking interaction with the conserved Phe in EL2; therefore, possible conformational changes determined by rigidified substituents interacting with the loop could change the orientation of this Phe and its interaction with the ligand.

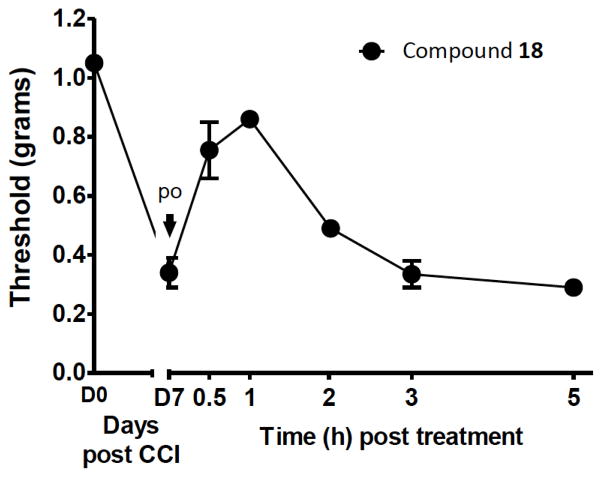

Although the molecular weight of this chemical series is outside the optimal range for oral bioavailability (MW 558; cLogP 2.63; total polar surface area 134 Å), one derivative 18 was tested in the CCI model after oral administration, following the general method previously described.25 It displayed considerable activity in reversing chronic neuropathic pain (Figure 2). This likely reflects the very high A3AR affinity and selectivity of this compound series. The peak effect occurred 1 h post-administration.

Figure 2.

Activity of 18 in a model of chronic neuropathic pain (mechanoallodynia), performed as described (po, oral administration).25 Paw withdrawal threshold is shown as a function of time. The nucleoside was administered by gavage at the time of peak pain (7 days after chronic constriction injury).

In conclusion, we have identified a group of highly rigidified and spatially extended nucleosides that were shown to be selective A3AR agonists. Rigid substituents at N6 and C2 positions, each of which was previously established as being conducive to A3AR binding, were combined. The activity of a representative compound in a clinically relevant in vivo pain model was demonstrated. Given these pharmacologically important properties, the conformational analysis of receptor binding was analyzed. The steric constraints of this molecular series allow us to probe the environment and propose specific amino acid interactions when receptor-bound. The conformationally constrained N6 group in docking to an A3AR homology model formed clear hydrophobic interactions with the normally flexible EL2. The conformational mobility of residues in this loop in the closely related A2AAR structures was noted, based on a comparison of agonist-bound and antagonist-bound structures.2 This study introduces sterically well-defined ligands that have rigid projections that can define the conformations of the A3AR in the TM and outer regions that are required to accommodate these ligands. This study introduces tools that will aid in the understanding of the role of receptor plasticity (in particular within the EL regions) in receptor recognition and activation.

Supplementary Material

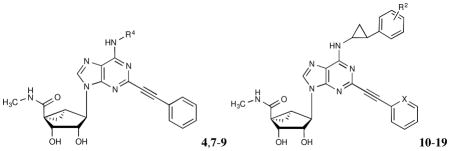

Chart 1.

Progression of SAR studies of A3AR agonists containing bulky N6 substituents, such as trans-2-phenylcyclopropyl, and modification of the ribose as a ring-constrained bicyclic system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Lloyd and Dr. Noel Whittaker (NIDDK) for mass spectral determinations. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK and R01HL077707).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EYT, Lane JR, IJzerman AP, Stevens RC. Science. 2008;322:1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu F, Wu H, Katritch V, Han GW, Jacobson KA, Gao ZG, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebon G, Warne T, Edwards PC, Bennett K, Langmead CJ, Leslie AG, Tate CG. Nature. 2011;474:521. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman P, Bar-Yehuda S, Liang BT, Jacobson KA. Drug Disc Today. 2012;17:359. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lera Ruiz M, Lim YH, Zheng J. J Med Chem. 2014;57:3623. doi: 10.1021/jm4011669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baraldi PG, Preti D, Borea PA, Varani K. J Med Chem. 2012;55:5676. doi: 10.1021/jm300087j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller C, Jacobson KA. Biochem Biophys Acta - Biomembranes. 2011;1808:1290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchilibon S, Kim SK, Gao ZG, Harris BA, Blaustein J, Gross AS, Melman N, Jacobson KA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tosh DK, Deflorian F, Phan K, Gao ZG, Wan TC, Gizewski E, Auchampach JA, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4847. doi: 10.1021/jm300396n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tchilibon S, Joshi BV, Kim SK, Duong HT, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1745. doi: 10.1021/jm049580r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paoletta S, Tosh DK, Finley A, Gizewski E, Moss SM, Gao ZG, Auchampach JA, Salvemini D, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 2013;56:5949. doi: 10.1021/jm4007966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melman A, Wang B, Joshi BV, Gao ZG, de Castro S, Heller CL, Kim SK, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:8546. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohno M, Gao ZG, Van Rompaey P, Tchilibon S, Kim SK, Harris BA, Blaustein J, Gross AS, Duong HT, Van Calenbergh S, Jacobson KA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:2995. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JP, Chessell I, Malamut R, Perkins M, Bačkonja M, Baron R, Farrar JT, Field MJ, Gereau RW, Gilron I, McMahon SB, Porreca F, Rappaport BA, Rice F, Richman LK, Segerdahl M, Seminowicz DA, Watkins LR, Waxman SG, Wiech K, Woolf C. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1255:30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman R. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:500. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. Pain. 1988;33:87. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwabe U, Trost T. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1989;313:179. doi: 10.1007/BF00505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams MJ. Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:978. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), version 2012.10. Chemical Computing Group Inc; 1255 University Street, Suite 1600, Montreal, Quebec, H3B 3X3, Canada: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrödinger Suite. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenzi O, Colotta V, Catarzi D, Varano F, Poli D, Filacchioni G, Varani K, Vincenzi F, Borea PA, Paoletta S, Morizzo E, Moro S. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7640. doi: 10.1021/jm900718w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Janes K, Chen C, Doyle T, Tosh DK, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. FASEB J. 2012;26:1855. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng R, Oliver S, Hayes MA, Butler K. Drug Metab Disposition. 2010;38:1514. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.032250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.