Abstract

Objectives

To characterize determinants of career satisfaction among pediatric hospitalists working in diverse practice settings, and to develop a framework to conceptualize factors influencing career satisfaction.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with community and tertiary care hospitalists, using purposeful sampling to attain maximum response diversity. We employed close- and open-ended questions to assess levels of career satisfaction and its determinants. Interviews were conducted by telephone, recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Emergent themes were identified and analyzed using an inductive approach to qualitative analysis.

Results

A total of 30 interviews were conducted with community and tertiary care hospitalists, representing 20 hospital medicine programs and 7 Northeastern states. Qualitative analysis yielded 657 excerpts which were coded and categorized into four domains and associated determinants of career satisfaction: (i) professional responsibilities; (ii) hospital medicine program administration; (iii) hospital and healthcare systems; and (iv) career development. While community and tertiary care hospitalists reported similar levels of career satisfaction, they expressed variation in perspectives across these four domains. While the role of hospital medicine program administration was consistently emphasized by all hospitalists, community hospitalists prioritized resource availability, work schedule and clinical responsibilities while tertiary care hospitalists prioritized diversity in non-clinical responsibilities and career development.

Conclusions

We illustrate how hospitalists in different organizational settings prioritize both consistent and unique determinants of career satisfaction. Given associations between physician satisfaction and healthcare quality, efforts to optimize modifiable factors within this framework, at both community and tertiary care hospitals, may have broad impacts.

Keywords: hospital medicine, community hospital, children's hospital, physician satisfaction, qualitative methods

Introduction

Physician satisfaction has implications for individual physicians as well as their colleagues, employers, and patients. Several past studies have illustrated associations between physician satisfaction and mental health, symptoms of burnout, and plans to discontinue employment.1-15 Increasing evidence also suggests that career satisfaction has implications for healthcare quality, with studies demonstrating associations between physician and patient satisfaction and between physician satisfaction and risk of medical errors. 16-20

In response, leaders in pediatric hospital medicine have identified assessment of career satisfaction as a priority.21 Hospital medicine is the fastest growing specialty in pediatrics with hospitalists engaging in diverse roles at community and tertiary care children's hospitals.21-23 Although prior research has examined determinants of career satisfaction among adult hospitalists,8-10,24 research exploring how pediatric hospitalists’ responsibilities and work environments may influence career satisfaction is, to our knowledge, limited to one previous study.25

The objectives of our study were to characterize determinants of career satisfaction among pediatric hospitalists working in children's hospitals and general community hospitals and to develop a framework to conceptualize factors influencing career satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative approach was employed to explore the multifaceted issues that influence career satisfaction. Semi-structured phone interviews lasting from 30-60 minutes were conducted by one of two physician interviewers (JL, LC) during May-July 2012. Participants also completed a standardized questionnaire to characterize their demographic characteristics and professional roles.

Study Population

Pediatric hospitalists working in the Northeast United States were eligible to participate if they worked outside the hospital network of the study team and did not have a personal relationship with the interviewer. For maximum response diversity, we used a purposeful sampling strategy26 to represent hospitalists working at community hospitals (general hospitals with pediatric beds) and tertiary care children's hospitals (freestanding children's hospitals or children's hospitals within larger institutions), with hospitalists allocated according to self-reported primary work location. The sample of pediatric hospital medicine programs was established by accessing publicly available lists of hospitals with pediatric beds and/or by confirming the existence of pediatric hospital medicine programs with hospitalist contacts in each state. No incentives were provided. Interviews were continued with hospitalists until thematic saturation was reached.26

Procedures

Determinants of career satisfaction were explored using close- and open-ended questions designed to elicit unbiased answers (Supplemental Digital Content Table). Consistent with previous studies, interviewees also rated their career satisfaction on a 10 point scale, with 10 being entirely satisfied.27-28 Prior to study initiation, the interview guide was pilot tested with hospitalists, not included in the final sample, to ensure that the questions were clear and motivated detailed responses. Participants provided verbal consent to participate and to have their interviews recorded. The Tufts Medical Center IRB provided study approval.

Data analysis

The interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim with personal identifiers removed, and transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose, a mixed-methods data management program (Version 4.3.87 (2012) Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC), which facilitates interview coding and thematic analyses. Two analysts (JL, EO) reviewed all transcripts to identify excerpts (sections of text describing concepts related to career satisfaction) and an inductive approach26 was used to identify preliminary themes related to career satisfaction. A codebook was developed to outline emergent themes and associated definitions, and two analysts (JL, EO) independently applied codes to five interviews. With the final coding structure determined, each analyst separately reviewed transcripts until agreement occurred consistently in the codes applied.29 Related emergent themes were subsequently grouped into domains to inform our conceptual framework. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the quantitative data, including medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical data.

Results

Interviews were conducted with 30 pediatric hospitalists, including 15 community hospitalists and 15 tertiary care hospitalists, a sample size falling within the range recommended by qualitative methodologists.30 Six participants self-identified as hospitalist program leaders, representing both tertiary care and community hospital medicine programs. Five physicians declined participation – two were not currently practicing as hospitalists, two were unable to commit the time, and one did not disclose a reason. Participating hospitalists represented twenty different hospital medicine programs at seven Northeastern states. Community and tertiary care hospitalists differed with respect to their clinical responsibilities, professional roles and schedule types (Table 1). Overall levels of career satisfaction were similar, with a median career satisfaction rating of 8 and range of 4 to 10.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, clinical and non-clinical roles, and ratings of career satisfaction of pediatric hospitalists.

| Characteristic | All hospitalists (n=30) Median [IQR] or n (%) |

Community hospitalists (n=15) Median [IQR] or n (%) |

Tertiary care hospitalists (n=15) Median [IQR] or n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 17 (57%) | 10 (67%) | 7 (47%) |

| Age (years) | 39 [36-45] | 41 [38-47] | 38 [36-43] |

| Hospital medicine experience (yrs) | 5 [4-8] | 5 [4-12] | 6 [3-7] |

| Work hours | |||

| Full time | 25 (83%) | 12 (80%) | 13 (87%) |

| Schedule type | |||

| Shift schedule | 19 (63%) | 15 (100%) | 4 (27%) |

| Block schedule | 11 (37%) | 0 | 11 (73%) |

| Clinical responsibilities | |||

| Inpatient unit | 29 (97%) | 14 (93%) | 15 (100%) |

| Emergency room | 10 (33%) | 9 (60%) | 1 (7%) |

| Normal nursery | 13 (43%) | 13 (87%) | 0 |

| Delivery room | 10 (33%) | 10 (67%) | 0 |

| Sedation service | 2 (7%) | 0 | 2 (13%) |

| Non-clinical responsibilities | |||

| Medical education | 26 (87%) | 12 (80%) | 14 (93%) |

| Research | 14 (47%) | 3 (20%) | 11 (73%) |

| Quality improvement | 24 (80%) | 11 (73%) | 13 (87%) |

| Guideline development | 22 (73%) | 11 (73%) | 11 (73%) |

| Hospital administration | 20 (67%) | 8 (53%) | 12 (80%) |

| Program leadership | 6 (20%) | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) |

| Career satisfaction rating – 10 point scale (range) | 8 [7-9] (range 4-10) | 7.5 [7-8] (range 4-10) | 8 [7-9] (range 6-10) |

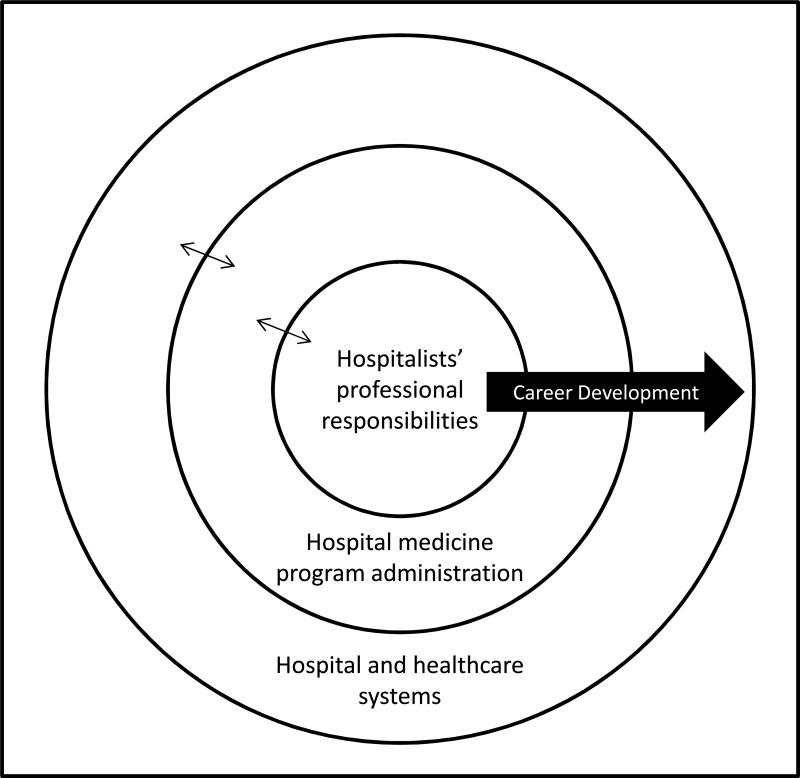

Qualitative analysis yielded 657 excerpts that were coded to characterize determinants of career satisfaction. Coded excerpts aligned with four domains: (i) professional responsibilities; (ii) hospital medicine program administration; (iii) hospital and healthcare systems; and (iv) career development. Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework illustrating how these domains correspond with the organizational systems in which pediatric hospitalists work, using an adaptation of Brofenbrenner's ecological systems theory.31-32 Table 2 provides representative quotes aligning with these domains.

Figure 1.

Determinants of pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction, demonstrating how organizational levels have bidirectional influences on career satisfaction. Hospitalists’ professional responsibilities, at the core (micro-level), are embedded within both the hospital medicine program administration (meso-level) and the larger hospital and healthcare system (exo- and macro-level), an adaptation of Brofenbrenner's ecological systems theory.30,31

Table 2.

Found domains and corresponding determinants of career satisfaction among pediatric hospitalists working in community and tertiary care hospitals with associated representative quotes.

| Determinants of career satisfaction | Key concepts described | Representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| DOMAIN 1: PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES | ||

| Clinical responsibilities | -areas of clinical coverage -professional satisfaction in clinical work -engagement with patients in hospital setting |

“So the variety is definitely important for me...the high acuity, short attention span aspect of it is perfect for me.” “I love patient interaction. I love hearing stories. I love trying to figure out how it all fits together. So that is what I find so satisfying.” |

| Non-clinical responsibilities | -program leadership -medical education -research -administrative tasks |

“You are expected to...produce something in education and research...which I think most of us find really meaningful.” “My patient care is good, but my teaching is outstanding. And it's the thing I take the most pride in.” “...having to worry about how many patients you are seeing, how well you are billing, how much money you are making for the hospital. If you could just see patients and not care about any of that stuff...” |

| Role diversity/workload | -breadth of roles and responsibilities and implications thereof -time and energy required to complete task |

“For me, job satisfaction is the opportunity to do multiple projects, to have a sense of self direction.” “I'm an associate program director, which is supposed to be 20 percent of my time. And I'm medical director of a unit, which is supposed to be half of my time. ...and I'm the head of quality improvement. So that adds up to a lot of time...” |

| Autonomy | -self-direction in clinical and non-clinical responsibilities | “We don't have specialists, so we are on the phone with the specialists. That sometimes makes it a little bit harder, but it also makes it 'funner' because then we get to manage the patient ourselves.” “I'm not my own boss, but I am allowed to develop my own career and pursue my own interests in the way that I want.” |

| DOMAIN 2: HOSPITAL MEDICINE PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION | ||

| Colleagues & work environment | -relationships with and support of colleagues -atmosphere of work environment |

“I love the people that I work with.” “If you're in a small place, you have a small number of people. So if there's one person who you don't quite think with, that's a pretty big portion of your colleagues.” |

| Work schedule | -work hours -shift length -schedule flexibility -schedule implications of understaffing |

“The one thing I find very hard is the schedule irregularity that I think is inherent to hospitalists...I think that my job satisfaction would go up a little bit if I had regular hours.” “I love shift work. And I love the flexibility it gives me.” “We're all just very tired right now – we're only operating at about 70-75% capacity now with our missing physician.” |

| Compensation | -salary and benefits -compensation for non-clinical responsibilities |

“I picked pediatrics fully knowing about getting paid. I don't need to be a millionaire.” “I think that yearning over, you know, little bits of differences between here and there is really kind of silly considering where we all start.” |

| Program leadership | -relationship with the program leader -strengths and weaknesses of the program leader |

“So I think that there is a lot of things on a systems basis that could potentially be addressed, but we can't do that, with [program leader].” “She has just been extremely supportive throughout the entire process. She has been able to guide me through some of these negative episodes and...keep my spirits boosted...” |

| DOMAIN 3: HOSPITAL AND HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS | ||

| Availability of resources | -availability of physical resources and personnel to practice effectively | “So I'm left with what's available at the community center, which is not always geared towards what we need both in terms of clinical support, educational support, and then sometimes even just functional equipment.” “More supportive infrastructure would help out a lot.” |

| Institutional support | -perceived support from other hospital divisions, departments | “I feel like we're frequently overshadowed and not given, sort of due attention.” “...get treated unfairly because they are always looked at us as a low revenue-generating department that they desperately need in order to be able to deliver babies.” |

| Hospital management | -hospital management style -relationship between hospital management and pediatric hospitalists |

“I do find that we have an unusually, at least in my perspective, open-minded administration, so that actually makes.my job satisfaction more positive.” “When things come from the top down, there are administrative things that are just nonsense.” “The upper management of the hospital is fairly divorced from the people doing the clinical work.” |

| The field of pediatric hospital medicine | -development of pediatric hospital medicine as a field nationally | “...Make it a specialty or make it a field. Because then I think it takes on a new level of respect, and some of those issues don't become as relevant.” “We have a little 10% carve out with the Society of Hospital Medicine and we might struggle even more as pediatric hospitalists to sort of find out where is our identity.” |

| National and regional healthcare systems | -factors related to regional and national healthcare systems | “We see large hospitals and large healthcare systems continuing to struggle financially. I think there are increasing business bureaucrats making decisions about who does what and everything else.” “I, probably like many physicians in the United States, find the U.S. healthcare system to be somewhat exasperating and frustrating....” |

| DOMAIN 4: CAREER DEVELOPMENT | ||

| Personal recognition | -recognition and appreciation from colleagues and leaders -opportunities for academic advancement |

“So I think I would feel more satisfied once I finally earn a promotion.” “Some recognition of being a teacher as opposed to a lab researcher would improve my satisfaction.” |

| Career trajectory | -interest in and awareness of career direction -availability of support to pursue career direction |

“I think because of the variety and the newness of the specialty, that it's difficult to figure out how to advance, or where to go, or how to make yourself better. And that can be frustrating as far as, you know, when you think about your future or your future ambitions.” “I think I'm also just getting my bearings in terms of where I want to head academically, and I think that's very stressful at this period of my life.” |

| Mentorship | -availability of mentorship -roles played by mentors |

“Finding better tracks and mentorship and more structured systems for a scholarship, especially for junior folks, would be really helpful...” “Now you are supposed to mentor, but you still need a lot of mentorship.” |

| Ongoing education | -opportunities for and suitability of continuing medical education and faculty development | “I have to have that regular kind of grand rounds, lectures, presentation type of thing just to keep my own education going. If I were to be in a community where there was none of that I would not want that for my job or my career.” “I would like more time for faculty development.” |

Professional responsibilities

Determinants of career satisfaction aligning with professional responsibilities included: (i) clinical responsibilities, (ii) non-clinical responsibilities, (iii) workload and role diversity, and (iv) autonomy.

With respect to clinical responsibilities, both tertiary care and community hospitalists described high levels of satisfaction in improving the health of children, forming relationships in hospital settings, and solving diverse clinical problems. Non-clinical responsibilities were also described as influential to career satisfaction by both hospitalist groups, particularly roles in medical education and program leadership. As articulated by one tertiary care hospitalist, “I enjoy that back and forth [with residents], and I think that's part of the reason my job satisfaction is high, in the sense that I get to interact with them every day, and keep learning.” Community hospitalists more frequently described insufficient teaching opportunities as negative determinants of satisfaction. In the words of one community hospitalist, “Ultimately my hope [is] for an ideal teaching role – residents, students,” while another stated, “I ultimately have a great interest in working with medical students and that has been difficult to get the more community-oriented hospitalists to be interested in.”

Five of the six hospitalists with program leadership responsibilities, from both community and tertiary care hospitals, reported that these responsibilities influenced their career satisfaction. Among these, four of the five hospitalists described their leadership responsibilities as having a negative influence on their career satisfaction, describing poor job fit for leadership positions. In the words of one tertiary care hospitalist, “I’m a medical director… and I honestly do not see myself going long term. Medical administration is not my goal.” Similarly, one community hospitalist stated, “I have been in a management position, and I’m perhaps not the best person to do that job – to manage other people.” In describing her career satisfaction, another community hospitalist stated, “I probably would have given it a ten if I wasn't the chief...”

Role diversity/workload was discussed by all tertiary care hospitalists and approximately half of community hospitalists, with most emphasizing how their varied roles positively influenced their satisfaction. Tertiary care hospitalists frequently discussed broad engagement in non-clinical roles as a positive determinant of satisfaction with one hospitalist reporting, “For me, job satisfaction is the opportunity to do multiple projects,” In contrast, role diversity was most frequently discussed by community hospitalists in the context of multiple clinical responsibilities, with one hospitalist reporting, “We wear many hats,” while another stated, “I personally prefer there to be a variety of responsibilities on the job.”

Hospital medicine program administration

Administration of hospital medicine programs was identified by all hospitalists as a determinant of career satisfaction. Four determinants of career satisfaction aligned with this domain: (i) colleagues and work environment, (ii) work schedule, (iii) compensation, and (iv) program leadership.

Colleagues and work environment were discussed as determinants of career satisfaction by both community and tertiary care hospitalists, with both physician and non-physician colleagues described as supportive and highly influential to hospitalist satisfaction. One hospitalist reported, “Maybe even the number one determinant [of career satisfaction] for me is coworkers.” Another stated, “We all practice medicine very differently and that leads to some disagreements, but we are very, very respectful and we are very, very supportive of one another. So I think that having partners that you really work well with is so, so important.”

Among some community hospitalists, shift-work was discussed as a positive determinant of their satisfaction, while others described schedule irregularity, burden of night and weekend responsibilities, shift length, and total number of hours worked as negative factors. There was no consistency regarding perceived “ideal” shift length, as hospitalists expressed variable preferences for 8-, 12-, or 24-hour shifts. Schedule-related flexibility was described as positively impacting career satisfaction by hospitalists practicing in both settings, with one tertiary care hospitalist reporting, “Flexibility and time, I think, is just really key. More important than total hours worked, just being able to have flexibility in your schedule.” In contrast, the negative impact of hospitalist turnover and associated understaffing on work schedules was raised by almost half of hospitalists, more frequently at community hospitals. Understaffing was described as leading to program instability, undesirable increases in work hours, and significant personal and program-level stress.

Compensation was frequently discussed as influential to career satisfaction with approximately equal frequency among community and tertiary care hospitalists. One tertiary care hospitalist reported, “So I think within my hospital structure and compared to my colleagues, I am compensated fairly. I just think in general that pediatricians as well as pediatric hospitalists are really undervalued.” Dissatisfaction with lack of compensation for non-clinical responsibilities was reported by six hospitalists, with one reporting, “…they just keep piling it on and they don’t change what they pay you.”

Program leadership was discussed as both a positive and negative adeterminant of satisfaction, particularly by tertiary care hospitalists. Effective leaders were described as supportive, flexible, transparent, creative and accessible, with one hospitalist stating, “I’ve been really surprised...at how incredibly important your individual boss is, how that can make such a huge difference in term of the quality of your own experience.” In contrast, a relative lack of experience was described as contributing to ineffective program leadership by other hospitalists in our sample. One hospitalist described, “It's hard for him because he doesn’t really understand the institution, but I also feel like he is not at a point in his career where he is really invested in growing and sustaining a program.” Another tertiary care hospitalist stated, “We actually therefore need a clear hospitalist leader. We don’t have a hospitalist leader.”

Hospital and healthcare systems

Hospital and healthcare systems were discussed by almost all hospitalists (n=29), with representative quotes illustrated in Table 2. Determinants of career satisfaction associated with this domain included: (i) availability of resources, (ii) institutional support, (iii) hospital management, (iv) field of pediatric hospital medicine, and (v) national and regional healthcare systems.

Availability of resources was emphasized as a factor influencing the career satisfaction of all community hospitalists (n=15). Resource limitations discussed by respondents included physical workspace, medical technology for pediatric procedures, administrative support, and information technology. Although community hospitalists described strong positive relationships with non-physician staff, limited pediatric skills of ancillary staff were described as negative factors by two thirds of community hospitalists, an issue not raised by tertiary care hospitalists. One community hospitalist reported, “...the nursing staff...they don't feel comfortable with a lot of acuities. So even when you feel like you are comfortable dealing with a problem, you can’t.”

Both community and tertiary care hospitalists discussed the importance of institutional support to their career satisfaction, reporting a perceived lack of respect and recognition compared to other departments and subspecialties. This was attributed to relatively low revenue generation, limited appreciation for non-clinical activities, and the youth of hospital medicine divisions. One tertiary care respondent reported, “I think in an academic center…rather than being the source of revenue for the subspecialists, you are now sort of a lowly little sibling.”

Hospital management was reported as influential to career satisfaction of 11 hospitalists, with equal frequency by community and tertiary care hospitalists. Most respondents (n=9) described hospital management as a negative determinant of their career satisfaction, citing a “top down” management style, a lack of transparency, and a lack of understanding of hospital medicine.

Healthcare systems, both regional and national, were discussed as determinants of career satisfaction by hospitalists in both community and tertiary care settings, particularly by hospitalist program leaders. Both tertiary care and community hospitalists described the negative impact of financial pressures on healthcare systems, “business bureaucracy,” and healthcare reform on their career satisfaction.

Respondents also discussed the development of pediatric hospital medicine as a field, articulating a desire to have hospitalists’ roles more clearly defined at a national level to effectively advocate for recognition, compensation and support. One hospitalist reported, “I think as a field...we're still defining ourselves and sometimes that's challenging,” while another stated, “I do think that nationally we have to define our role, think about how do we advocate for hospitalists, particularly pediatric hospitalists.”

Career development

Career development was discussed by almost all tertiary hospitalists and approximately half of community hospitalists. Determinants of career satisfaction within this domain included: (i) recognition, (ii) career trajectory, (iii) mentorship, and (iv) continuing medical education (CME).

Personal recognition was discussed more frequently by tertiary care hospitalists than community hospitalists, with comments focused on accolades by patients and colleagues, receipt of awards, and opportunities for academic advancement. Hospitalists discussed lack of recognition as a negative determinant of career satisfaction, with one tertiary care hospitalist reporting, “I felt much more valued as a resident than I do as an attending at the same institution,” while a community hospitalist reported, “But we're still relegated to a resident role essentially, and that's not what I was ever looking for.”

Difficulties visualizing a career trajectory were discussed by several hospitalists, with one community hospitalist stating, “I would want to feel that I’m growing as a person and as a physician, and I don’t think that I could do this for 20 years and feel that, the way it is now…” Similarly, one tertiary care hospitalist stated, “I’m trying to figure out what is my five to ten year plan. Maybe I’m having sort of a mid-life hospitalist crisis. I have accomplished a lot of what I wanted to do in the first five years in the field. And so now I am trying to figure out – where do I want to go forward?” Related to this, a lack of mentorship was raised as a negative factor by approximately one third of hospitalists, with greater frequency among tertiary care hospitalists. As articulated by one hospitalist, “The irony is that I am at the age where I am sort of becoming a mentor and I feel like I am not supposed to have a mentor because I’m supposed to be the mentor. It would be really nice to have somebody in my department who I felt could help me with my professional development.”

Limited opportunities for CME were described by both community and tertiary care hospitalists who expressed desires for educational opportunities that were tailored to their professional responsibilities. One community hospitalist reported, “It would be wonderful if we could get more time, protected time for CME, and not for fluff CME...but for the real thing, like to give me time in the operating room to do intubations,” while a tertiary care hospitalist stated, “That would be something I would have said is missing, which is now starting here, which is for us to continue learning ourselves.”

Discussion

We employed qualitative methods to explore factors influencing the career satisfaction of pediatric hospitalists working at community and tertiary care hospitals, developing a framework for hospitalists, physician leaders and organizational management to conceptualize determinants of career satisfaction. While the four domains characterized in our research - professional responsibilities, program administration, hospital and healthcare systems, and career development - were relevant to both community and tertiary care hospitalists, there was variation in perspectives regarding the determinants of satisfaction within these areas. Professional responsibilities and program administration were consistently discussed by all hospitalists. However, while community hospitalists emphasized diversity in clinical responsibilities, resource availability and work schedules, tertiary care hospitalists’ prioritized diversity in non-clinical responsibilities and career development. Our findings align with previous quantitative studies demonstrating relatively high levels of career satisfaction of hospitalists,25,33 while providing important contextual details to understand how varied organizational settings influence career satisfaction.

Recognizing the importance of career satisfaction in physician retention and program growth, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) issued a White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction in 2006, proposing a framework that identified four “pillars” of career satisfaction: (i) reward/recognition; (ii) workload/schedule; (iii) autonomy/control; and (iv) community/environment.24 One previous study examining career satisfaction among pediatric community and academic hospitalists applied this SHM framework, concluding that community hospitalists seemed less satisfied than academic hospitalists and noting significant differences between these hospitalist groups in self-reported opportunities for academic advancement, value by hospital administration and professional stimulation by colleagues.25,33 Our study builds on this work, applying an inductive approach to identify determinants of career satisfaction and develop a conceptual framework specific to pediatric hospitalists. Unlike the work by Pane et al., our results suggest similar levels of reported career satisfaction among community and tertiary care hospitalists, with variation in its determinants. Aligning with the SHM framework, our research supports the roles of recognition, schedule and work environment in hospitalist career satisfaction. In addition, our results illustrate the relevance of non-clinical responsibilities, program administration and leadership, institutional support, and career development opportunities. Consistent with research in other disciplines, our research also illustrates the effects of organizations on individuals’ work experiences and satisfaction.34

The importance of program administration to hospitalists’ career satisfaction is juxtaposed with our finding that several hospitalist program leaders described leadership responsibilities as negative determinants of their own career satisfaction. A lack of formal leadership training at most medical schools and residency programs, coupled with relatively junior faculty in positions of hospital medicine leadership may result in ill-defined expectations and training for leadership positions.24,35 Leadership skills have been proposed as core competencies for all hospitalists and are reflected in the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies.36 Supporting hospitalists as they move into leadership roles with mentoring, training, and protected time may improve the career satisfaction of both hospitalist leaders and non-leaders. Attention to other modifiable factors related to program administration, such as supporting and enabling hospitalist mentorship and providing recognition for non-clinical responsibilities, may also significantly improve hospitalists’ career satisfaction. Recognizing the bidirectional relationships between hospital medicine program administration and hospital systems, increasing physician involvement in hospital management while being cognizant of workload implications may benefit both organizations and hospitalists.37

We chose semi-structured interviews to explore in depth the determinants of career satisfaction; by asking open-ended questions and applying systematic qualitative analysis, our results provide rich contextual details regarding the factors influencing pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction and how these factors may differ in varying organizational settings. The limitations of our methodological approach include the inability to generalize findings to pediatric hospitalists more broadly, given our geographic and purposeful sampling, potential response bias by participants given the personal nature of the subject area, and possible bias in data collection and analyses.38 Whether or not these research findings are generalizable will require application of our conceptual framework to inform a survey targeted to a nationally representative random sample of pediatric hospitalists.

Given associations between physician satisfaction and patient-level outcomes as well as physician retention, efforts to optimize modifiable factors within our career satisfaction framework may have broad impacts. Dissemination of best practices regarding administration of pediatric hospital medicine programs and effective engagement with hospital management and healthcare systems are important future areas of focus.

Supplementary Material

What's new.

Career satisfaction has implications for physician retention and healthcare quality. This study characterizes determinants of career satisfaction of hospitalists working in community and children's hospitals, providing a framework for hospitalists, physician leaders and organizational management to conceptualize determinants of satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Leyenaar was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1 RR025752. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest or corporate sponsors to report.

References

- 1.Embriaco N, Hraiech S, Azoulay E, et al. Symptoms of depression in ICU physicians. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Jul 27;2(1):34. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JV, Hall EM, Ford DE, et al. The psychosocial work environment of physicians. The impact of demands and resources on job dissatisfaction and psychiatric distress in a longitudinal study of Johns Hopkins Medical School graduates. J Occup Environ Med. 1995 Sep;37(9):1151–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renzi C, DiPietro C, Tabolli S. Pyschiatric morbidity and emotional exhaustion among hospital physicians and nurses: associations with perceived job related factors. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2012 Apr;67(2):117–23. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2011.578682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheurer D, McKean S, Miller J. U.S. physician satisfaction: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009 Nov;4(9):560–8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutherland VJ, Cooper CL. Identifying distress among general practitioners: predictors of psychological ill-health and job dissatisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Sep;37(5):575–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90096-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. Physician, practice, and patient characteristics related to primary care physician physical and mental health: results from the Physician Worklife Study. Health Serv Res. 2002 Feb;37(1):121–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doan-Wiggins L, Zun L, Cooper MA, et al. Practice satisfaction, occupational stress, and attrition of emergency physicians. Wellness Task Force, Illinois College of Emergency Physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 1995 Jun;2(6):556–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Apr 25;171(8):782–5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, et al. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Jan;27(1):28–36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, et al. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012 Jan 23; doi: 10.1002/jhm.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Apr;109(4):949–55. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258299.45979.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weng HC, Hung CM, Liu YT, et al. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. Med Educ. 2011 Aug;45(8):835–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright JG, Khetani N, Stephens D. Burnout among faculty physicians in an academic health science centre. Paediatr Child Health. 2011 Aug;16(7):409–13. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.7.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Williams ES, et al. Physician job satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and turnover. J Fam Pract. 2002 Jul;51(7):593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mainous AG, 3rd, Ramsbottom-Lucier M, Rich EC. The role of clinical workload and satisfaction with workload in rural primary care physician retention. Arch Fam Med. 1994 Sep;3(9):787–92. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Feb;15(2):122–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVoe J, Fryer GE, Jr, Straub A, et al. Congruent satisfaction: is there geographic correlation between patient and physician satisfaction? Med Care. 2007 Jan;45(1):88–94. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241048.85215.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007 Jul-Sep;32(3):203–12. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000281626.28363.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grembowski D, Paschane D, Diehr P, et al. Managed care, physician job satisfaction, and the quality of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Mar;20(3):271–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.32127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rauch DA, Lye PS, Carlson D, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A strategic planning roundtable to chart the future. J Hosp Med. 2011 Oct 12; doi: 10.1002/jhm.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lye PS, Rauch DA, Ottolini MC, et al. Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference. Pediatrics. 2006 Apr;117(4):1122–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freed GL, Dunham KM. Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric hospitalists: training, current practice, and career goals. J Hosp Med. 2009 Mar;4(3):179–86. doi: 10.1002/jhm.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force [September 12, 2012];A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction. Available at. 2006 Dec; http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Practice_Resources&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=14631.

- 25.Pane LA, Davis AB, Ottolini MC. Association between practice setting and pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction. Hospital Pediatrics. 2013;3(3):285–293. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2012-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119:1442–1452. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levinson W, Kaufman K, Bickel J. Part-time faculty in academic medicine: present status and future challenges. Ann Int Med. 1993;119:220–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-3-199308010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varner C, Ovens H, Letovsky E, Borgundvaag B. Practice patterns of graduates of a CCFP(EM) residency program: a survey. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e385–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics.;1977;33:378–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Amer Psychol. 1977;32:513–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darling N. Ecological Systems Theory: The Person in the Center of the Circles Research in Human Development. 2007;4:203–217. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pane LA, Davis AB, Ottolini MC. Career Satisfaction and the Role of Mentorship: A Survey of Pediatric Hospitalists. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2(3):141–148. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2011-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suchman AL, Deci EL, McDaniel SH, Beckman HB. Relationship-Centered Administration: Basic Principles and Examples from a Community Hospital. In: Frankel RM RM, Quill TE, McDaniel SH, editors. The Biopsychosocial Approach: Past, Present, Future. University of Rochester Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coltart CE, Cheung R, Ardolino A, et al. Leadership development for early career doctors. Lancet. 2012 May 12;379(9828):1847–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2010 Apr;5(Suppl 2):i–xv. 1–114. doi: 10.1002/jhm.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorgan S, Layton D, Bloo N, et al. [September 12, 2012];Management in healthcare: why good practice really matters. Available at: http://cep.lse.ac.uk/textonly/_new/research/productivity/management/pdf/management_in_Healthcare_Report.pdf.

- 38.Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;34(5 Pt 2):1101–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.