Abstract

Context:

Bacterial pathogens in dental plaque are necessary for the development of periodontitis but this etiology alone does not explain all its clinicopathologic features. Researchers have proven the role of certain viruses like herpes virus in periodontal disease which implies that other viral agents like human papilloma virus may also be involved.

Aims:

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the proportion of patients with human papilloma virus (HPV-16) in marginal periodontium by analyzing DNA from the gingival tissue sample and to understand its association with periodontitis.

Settings and Design:

102 systemically healthy patients between the age group of 15 and 70 years reporting to the Department of Periodontology who required surgical intervention (flap surgery for patients with periodontitis and crown lengthening for healthy patients) with internal bevel gingivectomy were selected.

Materials and Methods:

After scaling and root planning, gingival tissue was collected during the respective surgical procedure. DNA was isolated and amplified using specific primers for HPV-16 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The amplified products were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results:

No HPV DNA was detected in the 102 samples analyzed.

Conclusion:

Marginal periodontium does not contain HPV in this study population and hence there was no association between HPV and periodontitis.

Keywords: DNA, human papilloma virus, periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth. It has a multifactorial etiology, involving a complex interaction among specific bacteria, the host response, and risk factors.[1] It shows a variety of clinical presentations and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Theories proposed so far to explain the etiopathogeny of periodontitis have not been able to account for several clinical features of the disease including the failure of progression of all cases of gingivitis to periodontitis, site specificity, its episodic nature, etc.[2]

During the past two decades, different research groups suggested that periodontal tissues may serve as a reservoir for the herpes simplex virus (HSV),[3,4] Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),[4,5] and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV).[4,5] Furthermore, some of these studies showed that these viruses may be associated with the pathogenesis and severity of periodontal diseases. The abundance of herpes viruses in aggressive periodontitis lesions suggests a viral etiology in the development of the disease.[2]

Among the viral agents suggested, human papilloma virus (HPV) has also been known to contribute to periodontal infection.[6,7,8] HPV causes characteristic cytopathic effects (koilocytosis) and proliferation of epithelial cells.[9] Since proliferation and migration of the junctional epithelium are a major hallmark of periodontal breakdown, these known biological effects of HPV might provide a link between viral infection and periodontal disease.[1] Theoretically, the junctional epithelium attached to the tooth surface appears to fully serve the cellular functions required by HPV. It has a basal cell-like phenotype and does not differentiate. The basal cells are exfoliated through the gingival crevice before differentiation occurs.[10]

Aim of the present study is to determine the proportion of the patients with HPV in marginal periodontium by analyzing DNA from the gingival tissue sample and to find whether it has an association with periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee and was conducted between May and October 2010. An informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

102 systemically healthy subjects between the age group of 15 and -70 years reporting to the periodontology department, who required surgical intervention, were selected. The periodontitis group consisted of patients with a periodontal pocket depth of ≥5 mm who required flap surgery. Patients who required surgical crown lengthening for restorative purpose were considered in the healthy group. A total of 102 gingival tissue samples were removed by internal bevel incision during flap surgery and crown lengthening (67 samples from periodontitis group and 35 samples from healthy group). Pregnant females, patients with uncontrolled systemic diseases and smokers were excluded from the study. All samples collected were stored in RNA later (RLT) solution in −80°C [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Flap surgery with internal bevel incision

Figure 2.

Crown lengthening procedure with internal bevel incision

DNA extraction

From the homogenized tissues the DNA was extracted using AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit developed by Qiagen, Hilden, Germany. During the procedure the supernatant after centrifugation of the lysate was transferred to the All Prep DNA spin column. It was again centrifuged. Sequentially two buffers AW1 [guanidine hydrochloride] and AW2 were added to the column and centrifuged each time. Finally, nuclease-free water was added, incubated at room temperature for 1-5 minutes and then centrifuged to elute the DNA. Once isolated, DNA was stored at -20°C.

Detection of HPV-16 by the polymerase chain reaction technique

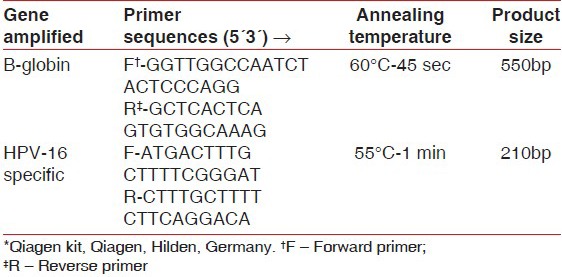

The presence of HPV-16 DNA was determined using a standard PCR and a PCR master mix [50 μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of PCR buffer, 1 μl of dinucleotidepeptides, 3 μl each of forward and reverse primers, 37.8 μl of nuclease-free water and 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase] developed by Qiagen, Hilden, Germany. One microliter of target DNA was added to this master mix during PCR. To verify the efficiency of the DNA extraction process, β-globin primers were used. For detecting HPV-16 virus, HPV-16-specific primer sequences were used [Table 1].

Table 1.

Primer sequence used for detection of β-globin and HPV 16 DNA*

Samples were collected after 35 cycles of amplification and the amplified product was checked by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide. Five microliter of DNA samples and ladder DNA which are stained with bromophenol blue was injected into the wells. The DNA bands were visualized with a UV transilluminator.

RESULTS

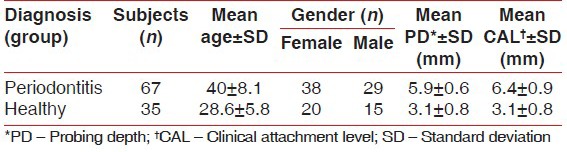

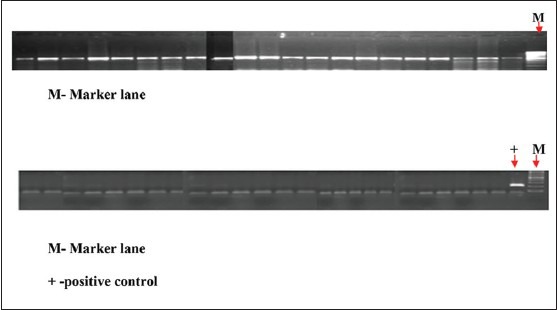

All the 102 DNA samples [Table 2] were of good quality because when amplified with β-globin primer, all the samples showed bright bands at the same location as shown by the positive control. But no such bright bands were obtained when amplified with HPV-16-specific primer. Hence, none of the tissue samples contained HPV-16 DNA. Thus, according to this study marginal periodontium did not act as a reservoir for HPV-16 [Figure 3].

Table 2.

The baseline characteristics of the study population

Figure 3.

The first figure shows the results from few samples checking the integrity of the isolated DNA by amplification with β-globin-specific primer. All samples were positive indicating that all DNAs extracted were of good quality. M-Marker lane and second figure shows the result on checking for HPV-16 positivity in the isolated DNA by amplification with HPV-16-specific primer. All samples were negative indicating that no HPV-16-specific DNA was detected. M-Marker lane + -positive control

DISCUSSION

In the present study HPV was selected because the association of HPV with periodontitis has been studied by various authors.[6,7,8] According to Hormia et al., chronic inflammation and continuous epithelial proliferation in the junctional and gingival sulcus epithelium in periodontitis could favor the replication of this virus and might be an important reservoir of HPV in the oral mucosa. HPV enters through micro-lesions or through normal exposure of parabasal cells to external environment. The only location in the oral mucosa where basal cells are exposed to the environment is the periodontal pocket.[6]

Marginal periodontium was selected in accordance with the study by Hormia et al., that marginal periodontal tissue in close association to teeth was expected to have the maximum receptors for HPV. This was obtained through internal bevel incision. The first step in viral infection is the attachment of the virus to a specific receptor on the surface of a susceptible host cell.[4] Integrin α6β4, a cell surface receptor for laminins, was preliminarily suggested to be the receptor for HPV entry.[11] HPV infection has been shown to require cell surface heparan sulfate, and especially syndecan-1 has been implied as the candidate receptor of HPV.[12] Heparan sulfate proteoglycans have also been detected in the dento-epithelial junction.[13] Thus, the marginal periodontal epithelial cells express the implicated HPV receptors needed by the virus for its entry into the host cells, giving strong additional support to the concept of an HPV reservoir in oral mucosa.

There are about more than 100 types of HPV and more than 30 are present in oral cavity.[14] It was difficult to test for all these 30 strains and hence HPV-16 was selected as it is one of the high risk HPV types most prevalent in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[8] A case control study by Tezal et al. showed that in a chronic periodontitis patient for each millimeter of alveolar bone loss there is a fourfold increase in the risk for oral squamous cell carcinoma. In that study 63% patients were positive for HPV-16.[15] Thus, the virus has an increasing importance in the present scenario.

Studies have shown that there is a positive association of HPV with periodontitis. Madinier et al. had shown a 16.6% prevalence of HPV in adult periodontitis and 50% prevalence in rapidly progressing periodontitis.[7] Another case-control study in Gingival Crevicular Fluid by Paras and Slots showed a prevalence of 17% in advanced periodontitis cases.[16] Hormia et al. had conducted a cross-sectional study in which gingival tissue sample showed a prevalence of 26%.[6] Till now the prevalence studies were carried out mostly on foreign population which included United States,[16] Argentina,[17] France,[7] Brazil[18] and Finland[6] and prevalence varied from 0% to 92.31%. There are no published studies on the prevalence of HPV in periodontal tissues of Indian Population.

This wide range may be due to several factors, such as inherent differences in the population being studied, different disease definitions, and the methods used for HPV detection. Madinier et al. obtained specimens from patients undergoing surgical extraction under general anesthesia in a hospital. Two patients were selected with acute gingivitis and either of them were psychiatric young patients with poor oral hygiene and untreated dental decay. Also, 2 out of 10 patients selected from AIDS patients were positive for HPV. Out of this only one out of the two psychiatric patients and one out of the ten AIDS patients were positive for HPV-16. AIDS patients are definitely immunocompromised and may be the reason for the presence of virus. Also the psychiatric patients may be susceptible to various infections as their lifestyle may be stressful, unhygienic and may even have certain systemic illness. In the present study only systemically healthy patients were selected. Also, in the study by Madinier et al. and Hormia et al., they have studied other HPV types including types 6, 11 and 18. Furthermore, it is not possible to conclude from these studies that HPV infection preceded periodontitis. These two infections may have occurred concurrently, or periodontitis may have preceded HPV infection. Further studies are needed to evaluate the temporal relationship of these two infections.

In the present study no HPV-16 DNA was detected from the collected samples and hence there was no association between HPV-16 and periodontitis in this study population. The results were in consistence with the study by Horewicks et al., in which negative results were obtained when tested for HPV-16 in periodontal tissue.[18] This emphasizes the fact that this particular type of HPV may be absent from marginal periodontium in a systemically healthy patient even if the patient has periodontitis. HPV-16 is a high risk virus which may be present only in tissues that had undergone carcinogenic transformation. This may be supported by the study by Tezal et al., where HPV-16 was detected from chronic periodontitis patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. The negative result in the present study may also be due to a smaller sample size. The better educational status and hygiene practice by the general population could also be a reason. Only a single type of HPV i.e., HPV-16 was tested in this study. Other types of HPVs may be present in the marginal periodontal tissue. Since papilloma viruses do not appear to exist in nature as passenger viruses, identification of HPV in a particular tissue in all likelihood establishes the etiology of the lesion. Failure to detect HPV, however, does not necessarily exclude it as the etiologic agent. Hence, it highlights the need for further studies on different types of the same virus with a larger sample size.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the study, HPV-16 was not detected in any of the tissue samples, indicating that this virus was not associated with the pathogenesis of periodontitis in systemically healthy patients. This reveals that the marginal periodontal tissue did not act as a reservoir for HPV-16 in the study population. However, other types of HPVs also need to be subjected to similar investigations. Only when all such HPV types commonly found in oral cavity are tested in a larger study population, the association of HPV and periodontitis can completely be ruled out. So, further studies are needed in this direction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dr. Bindu R. Nayar, Prof. and HOD, Department of Periodontics, GDC Trivandrum for all her valuable suggestions and Prof. M. Radhakrishna Pillai Director, Rajiv Gandhi Centre of Biotechnology (RGCB), Trivandrum for giving the opportunity to do the research at RGCB.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: Summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:216–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slots J. Human viruses in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:89–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amit R, Morag A, Ravid Z, Hochman N, Ehrlich J, Zakay-Rones Z. Detection of herpes simplex virus in gingival tissue. J Periodontol. 1992;63:502–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contreras A, Slots J. Mammalian viruses in human periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:381–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contreras A, Slots J. Active cytomegalovirus infection in human periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hormia M, Willberg J, Ruokonen H, Syrjanen S. Marginal periodontium as a potential reservoir of human papillomavirus in oral mucosa. J Periodontol. 2005;76:358–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madinier I, Doglio A, Cagnon L, Lefebvre JC, Monteil RA. Southern blot detection of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) DNA sequences in gingival tissues. J Periodontol. 1992;63:667–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang F, Syrjanen S, Kellokoski J, Syrjanen K. Human papilloma virus (HPV) infections and their associations with oral disease. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:305–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S. London: Wiley; 2000. Papillomavirus Infections in Human Pathology; pp. 1–615. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder HE. The junctional epithelium: Origin, structure and significance. Acta Med Dent Helv. 1996;1:155–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evander M, Frazer IH, Payne E, Qi YM, Hengst K, McMillan NA. Identification of the alpha 6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:2449–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2449-2456.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Sapp M. Analysis of the infectious entry pathway of human papillomavirus type 33 pseudovirions. Virology. 2002;299:279–87. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hormia M, Owaribe K, Virtanen I. The dento-epithelial junction: Cell adhesion by type I hemidesmosomes in the absence of a true basal lamina. J Periodontol. 2001;72:788–97. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Villiers EM, Neumann C, Le JY, Weidauer H, zur Hausen H. Infection of the oral mucosa with defined types of human papillomaviruses. Med Microbiol Immunol Berl. 1986;174:287–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02123681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tezal M, Sullivan Nasca M, Stoler DL, Melendy T, Hyland A, Smaldino PJ, et al. Chronic periodontitis-human papilloma virus synergy in base of tongue cancers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:391–6. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parra B, Slots J. Detection of human viruses in periodontal pockets using polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:289–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bustos DA, Grenón MS, Benitez M, de Boccardo G, Pavan JV, Gendelman H. Human papillomavirus infection in cyclosporin-induced gingival overgrowth in renal allograft recipients. J Periodontol. 2001;72:741–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horewicz VV, Feres M, Rapp GE, Yasuda V, Cury PR. Human Papillomavirus-16 Prevalence in Gingival Tissue and Its Association With Periodontal Destruction: A Case-Control Study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:562–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]