Abstract

Background:

There is a considerable intra and inter-individual variation in both width and thickness of the facial gingiva. As the attached gingiva is an important anatomic and functional landmark in the periodontium, the identification of gingival biotype is important in clinical practice since differences in gingival and osseous architecture have been shown to exhibit a significant impact on the outcome of restorative therapy. Hence, the aim of this study was to determine the variation in width and thickness of facial gingiva in the anterior segment with respect to age, gender and dental arch location.

Materials and Methods:

120 subjects were divided into three age groups: The younger age group (16-24 years), the middle age group (25-39 years) and the older age group (>40 years) with 20 males and 20 females in each group. The width of the gingiva was assessed by William's graduated probe and the thickness was determined using transgingival probing in the maxillary and mandibular anterior segment.

Results:

It was observed that the younger age group had significantly thicker gingiva but less width than that of the older age group. The gingiva was found to be thinner and with less width in females than males. The mandibular arch had thicker gingiva with less width compared to the maxillary arch.

Conclusion:

In the present study, we concluded that gingival thickness and width varies with age, gender and dental arch location.

Keywords: Attached gingiva, age, gingival thickness, gender, transgingival probing

INTRODUCTION

Attached gingiva is one of the most important anatomic and functional landmarks in the periodontium. It is defined as the distance between the mucogingival junction and the projection on the external surface of the bottom of gingival sulcus or the periodontal pocket. It is not synonymous with keratinized gingiva because the latter also includes the free gingival margin. An adequate width of the attached gingiva helps in maintaining esthetics and enhanced plaque control. Restoring an adequate width of attached gingiva is a part of the periodontal plastic and esthetic surgery. Sufficient thickness of the attached gingiva is desired as a thin and delicate gingival margin may lead to recession after trauma, surgical or inflammatory injuries. It may also aggravate the existing recession post operatively.

Normally, there is a considerable intra and inter-individual variation in both width[1] and thickness of the facial gingiva,[2] a fact that gives rise to the assumption that different gingival phenotypes might exist in any adult population. Müller and Eger in 1997[3] coined the term ‘gingival or periodontal phenotype’ to address a common clinical observation of great variation in thickness and width of facial keratinized tissue. The identification of gingival biotype may be important in clinical practice since differences in gingival and osseous architecture have been shown to exhibit a significant impact on the outcome of restorative therapy. In natural teeth Pontoriero and Carnevale (2001)[4] showed that more soft tissue regained following crown lengthening procedures in patients with a so-called thick flat biotype, than in those with a ‘thin scalloped biotype’. This observation is in line with a higher prevalence of gingival recession in the latter as reported by Olsson and Lindhe (1991).[2] Also, at implant restorations, the gingival biotype has been described as one of the key elements decisive for a successful treatment outcome. Various invasive and non-invasive methods can be used to assess the masticatory mucosa such as conventional histology on cadaver jaws, injection needle, transgingival probing, histologic sections, cephalometric radiographs and cone-beam computerized tomography (CBCT).

Most of the studies conducted earlier were either carried out on edentulous patients or they estimated only the thickness of the palatal masticatory mucosa. The palatal masticatory mucosa has a less bearing as far as aesthetics or gingival recession is concerned. Also, it was felt that literature needs to be augmented with regards to the understandings of thickness and width of gingiva in the anterior maxillary and mandibular sextants, which bear the maximum brunt of the gingival recession and have greater esthetic relevance.[2,3] Hence, the aim of this study was to determine the variation in width and thickness of facial gingiva in the anterior segment with respect to age, gender and dental arch location.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 120 systemically healthy adults participated in this study. Patients were selected randomly. Power analysis was performed to determine the sample size. As difference between width of attached gingiva of maxillary and mandibular arch was 1.15 with standard deviation of 1.21; α error (5%); Power (1-β) 90%, hence, minimum sample size required was 40. Prior to the study, purpose and the design of the study were explained to the patient and informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of VSPM Dental College and Research Centre, Nagpur, India. Periodontally healthy subjects with no loss of attachment and patients having all anterior teeth in the maxillary and mandibular arch and those who do not require special health care for daily activities were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were hospitalized patients, pregnant and lactating females, patients with gingival recession in the anterior teeth and extensive restorations and those under medication affecting the periodontium such as cyclosporin A, calcium channel blockers, phenytoin. The younger age group included subjects with 16-24 years of age, the middle age group comprised subjects between 25 and 39 years of age and the older age group having subjects of 40 years and above age. Each group had a population comprising of 20 males and 20 females.

In the first visit, Plaque Index (Turesky- Gilmore-Glickman modification of Quigley Hein plaque index 1970), Papillary Bleeding Index (Muhlemann and Son 1977) and Probing depth using a William's graduated periodontal probe were recorded followed by scaling and polishing.

After anesthetizing the facial gingiva with a Lidocaine spray (LOX 10%), the width of the attached gingiva was determined by stretching the lip or cheek and subtracting the sulcus or pocket depth from the total width of the attached gingiva that is from the marginal gingiva to mucogingival junction. This estimation was done using a periodontal probe fitted with an endodontic rubber stopper and the measurements were recorded with the help of a steel ruler calibrated at 1 millimeter. Gingival thickness was assessed midbuccally halfway between the mucogingival junction and the free gingival groove in the attached gingiva using an endodontic spreader fitted with a rubber stopper and measured on the ruler [Figure 1]. Measurements were not rounded off to the nearest millimeter. Both the width and the thickness of the attached gingiva were recorded for 6 maxillary and 6 mandibular anterior teeth. Measurement errors were minimized by allowing only one person (AM) to perform the measurements three times for each area and the most frequently measured and recorded readings were selected as the final measurement.

Figure 1.

Measurement of thickness of gingiva using an endodontic spreader

Statistical analysis

Mean width and thickness of gingiva were compared across different age groups by performing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The unpaired t-test was used to compare mean width and thickness of gingiva between male and female subjects and also to compare between maxillary and mandibular arches. Correlation coefficient was used to assess magnitude and nature of correlation between width and thickness of gingiva. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data was analyzed using statistical software STATA version 10.0. Data had normal distribution to use the t-test.

RESULTS

The mean width of attached gingiva in the maxillary arch and the mandibular arch for 16-24 years age group was 2.66 (±0.52) mm and 1.89 (±0.6) mm, respectively; for the middle age group (25-39 years) it was 2.82 (±0.54) and 2.11 (±0.53) mm, respectively and for the higher age group (>40 years) it was 3.71 (±0.50) mm and 3.04 (±0.48) mm, respectively. The width of the attached gingiva significantly increased with age for both the arches [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean width of attached gingiva in different age groups separately for maxillary and mandibular arch

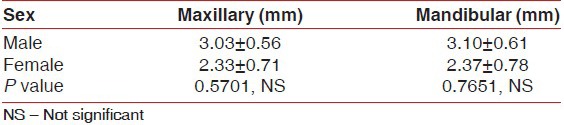

The mean width of attached gingiva in the maxillary arch and the mandibular arch in males was 3.03 (±0.56) mm and 3.10 (±0.61) mm, respectively; and for females it was 2.33 (±0.71) mm and 2.37 (±0.78) mm, respectively. The width of the attached gingiva was higher in males compared to females but not statistically significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean width of attached gingiva in different sex groups separately for maxillary and mandibular arch

The mean width of the attached gingiva was 3.06 (±0.69) mm and 2.35 (±0.74) mm for the maxillary arch and mandibular arch, respectively. This shows that it was significantly higher in maxilla compared to mandible (P < 0.0001).

The mean thickness of attached gingiva in the maxillary arch and the mandibular arch for 16-24 years age group was 1.60 (±0.43) mm and 1.70 (±0.59) mm respectively; for the middle age group (25-39 years) it was 0.86 (±0.26) mm and 0.91 (±0.25) mm respectively and for the higher age group (>40 years) it was 0.66 (±0.25) mm and 0.75 (±0.71) mm, respectively. The thickness of the attached gingiva significantly decreased with age for both the arches (P < 0.0001).

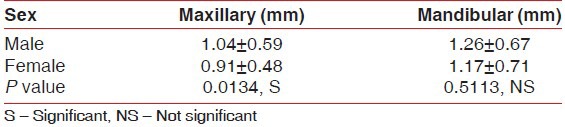

The mean thickness of attached gingiva in the maxillary arch and the mandibular arch in males was 1.04 (±0.59) mm and 1.26 (±0.67) mm, respectively, whereas in females it was 0.91 (±0.48) mm and 1.17 (±0.71) mm, respectively. The thickness of the attached gingiva was higher in males than females and showed significant difference in the maxillary arch for males and females, whereas it was non-significant in the mandibular arch [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean thickness of attached gingiva in different sex groups separately for maxillary and mandibular arch

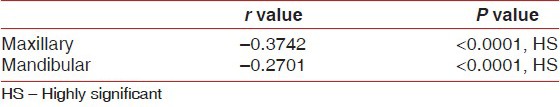

The mean thickness of the attached gingiva was 1.04 (±0.52) mm and 1.12 (±0.69) mm for the maxillary arch and mandibular arch, respectively. This shows that it was higher in mandible compared to maxilla but not significant (P > 0.0001). Table 4 shows that the thickness of the attached gingiva significantly decreased with an increase in the width for both the arches.

Table 4.

Correlation between width of attached gingiva with thickness separately for maxillary and mandibular arch

DISCUSSION

Various methods have been employed by research workers and clinicians to measure the thickness of gingiva, which is of immense importance considering their use in many therapeutic modalities for correction of mucogingival problems. The literature search reveals very limited clinical trials performed in this area and among these, majority have measured the thickness of masticatory mucosa on the palatal aspect, with a consideration that few of the therapeutic modalities employ palatal donor tissue for correction of the mucogingival problems. However, there are several other modalities, which rely on the adequacy of width of attached gingiva and thickness of gingiva on the buccal or facial aspects. Measurements of these parameters have been calculated by non-invasive methods such as application of ultrasonic devices and cone-beam computed tomography. Although the former method is more comfortable for the patient, the authors found difficulty in obtaining reliable results on a consistent basis.[5,6] The latter method using CBCT reveals a high quality image of hard and soft tissue and allows measurements of the dimensions and relationships of these structures. However, this method is unable to distinguish between normal and inflamed gingiva, which have similar images acquired by CBCT.[7] Hence, the measurements are likely to be unreliable in some of the cases. Transgingival sounding by means of a periodontal probe has also been used for this purpose, however, this method seems to be inconvenient for the patient because it is invasive and has been performed under infiltration local anesthesia.[8,9] The present study hence was conducted to determine the width and thickness of facial gingiva in the anterior sextant by a periodontal probe under adequate local anesthesia spray.

Analysis of the width of the gingiva and thickness was performed not only in three age groups i.e., younger (16-24 years), middle (25-39 years) and older (above 40 years) age groups, but the gender variability was also taken into consideration by having equal number of males and females (20 each) in all these age groups. There is lack of studies wherein age wise, gender wise and dental arch location specific comparisons of these parameters are reported. The results indicated that there was an increase in width of attached gingiva in both maxillary and mandibular arches, with the increasing age groups, which was more in the maxillary compared to mandibular arches. Also the width of the attached gingiva was found to be more in males as compared to females.

In our study, the thickness of the gingiva was found to be more in younger age group and reduced with the increasing age. These findings are similar to those reported by Vandana et al.[10] which can be because of change in oral epithelium caused by age related thinning of the epithelium and diminished keratinization. In our study, the thickness of the gingiva was recorded only on the midfacial aspect, as there could be existing variations in respect of midfacial and interdental recordings because the alveolar bone contours are different in these areas, which might influence the soft tissue thickness. So the recordings of our study seem to be more appropriate.

These findings are contrary to the observations of Waraaswapati et al.[9] who reported that the thickness of palatal masticatory mucosa also increased with the increasing age group. However, it may not be proper to compare the findings of facial gingiva with palatal mucosa in toto.

The study population in the present study comprised of equal number of males and females in each age group, which enabled comparisons with regards to gender. The results indicated that the thickness of attached gingiva was more in males as compared to the females in both maxillary and mandibular arches. These findings showed statistically significant differences for maxillary arches, whereas they were non-significant in mandibular arches. These results were consistent with those of Muller et al. 2000[11] and Song et al. 2008[12] and contrary to those reported by Barriviera et al. 2009[7] and Studer et al. 1997.[8] These variations in results can be attributed to the methods of measurements. In case of infiltration anesthesia, the thickness can be influenced by the anesthetic solution deposited, whereas in case of CBCT, the inflammatory tissues can lead to increase in measurements. Local anesthesia sprays with periodontal probe seem to be one of the best methods of assessing thickness of attached gingiva as the chances of errors are least likely to creep in.

One of the limitations of this study is the influence of the bucco-lingual tooth position within the alveolar process. Although adequate care was taken that the teeth were in proper arch positions, minor variations if any may also have effect on the gingival biotypes.

CONCLUSION

It has been demonstrated that the thickness of the gingiva reduces with an increase in age, whereas the width of the attached gingiva increases with increasing age in both maxillary and mandibular dental arches. With regards to gender, the males had greater thickness of attached gingiva when compared to female counterparts. However, other confounding factors such as tooth position, genetic and racial factors are also likely to influence the measurements, which may be a matter to be investigated in further clinical trials.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seibert J, Lindhe J. 2nd ed. Copenhangen: Munksgaard; 1989. Textbook of Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry; pp. 477–517. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson M, Lindhe J. Periodontal characteristics in individuals with varying form of the upper central incisors. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller HP, Eger T. Gingival phenotypes in young male adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pontoriero R, Carnevale G. Surgical crown lengthening: A 12-month clinical wound healing study. J Periodontol. 2001;72:841–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.7.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eger T, Müller HP, Heinecke A. Ultrasonic determination of gingival thickness. Subject variation and influence of tooth type and clinical features. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:839–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller HP, Schaller N, Eger T. Ultrasonic determination of thickness of masticatory mucosa: A methodologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:248–53. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barriviera M, Duarte WR, Janua×rio AL, Faber J, Bezerra AC. A new method to assess and measure palatal masticatory mucosa by cone-beam computerized tomography. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:564–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studer SP, Allen EP, Rees TC, Kouba A. The thickness of masticatory mucosa in the human hard palate and tuberosity as potential donor sites for ridge augmentation procedures. J Periodontol. 1997;68:145–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waraaswapati N, Pitiphat W, Chandrapho N, Rattanayatikul C, Karimbux N. Thickness of palatal masticatory mucosa associated with Age. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1407–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandana KL, Savitha B. Thickness of gingiva in association with age, gender and dental arch location. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:828–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller HP, Schaller N, Eger T, Heinecke A. Thickness of masticatory mucosa. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:431–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027006431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song JE, Um YJ, Kim CS, Choi SH, Cho KS, Kim CK, et al. Thickness of posterior palatal masticatory mucosa: The use of computerized tomography. J Periodontol. 2008;79:406–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]