Abstract

Invasive mold infections (IMIs) are a major source of morbidity and mortality among lung transplant recipients (LTR) yet information regarding the epidemiology of IMI in this population are limited. From 2001–2006, multicenter prospective surveillance for IMIs among LTR was conducted by the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. The epidemiology of IMI among all LTR in the cohort is reported. Twelve percent (143/1173) of LTRs under surveillance at 15 U.S. centers developed IMI infections. The 12-month cumulative incidence of IMIs was 5.5%; 3-month all-cause mortality was 21.7%. s caused the majority (70%)of IMIs; non-infections (39; 27%) included: (5), mucormycosis (3), and “unspecified” or “other” mold infections (31). Late-onset IMI was common: 52% occurred within one year post-transplant (median 11 months, range 0–162 months). IMIs are common late-onset complications with substantial mortality in LTRs. LTRs should be monitored for late-onset IMIs and prophylactic agents should be optimized based on likely pathogen.

Keywords: lung transplant, mold, infection, epidemiology

Background

Lung transplantation is a life-saving intervention for patients with end stage lung disease. In the United States in 2011, 1,849 lung and heart/lung transplant procedures were performed (1). Despite important advances in surgical technique, immunosuppressive regimens, and the development of novel antifungal agents in recent years, lung transplant recipients remain at substantial risk for development of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) (2). However, few data are available on the overall burden of IFIs in this population. Historical studies have been primarily limited to small retrospective investigations (2–5) from which conflicting results have been reported (6, 7) and limited conclusions can be drawn.

To better understand the burden of IFIs and their associated outcomes among transplant recipients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and partners formed the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET), a multicenter consortium designed to perform prospective surveillance for IFIs among selected major transplant centers in the United States. TRANSNET provides the most comprehensive epidemiologic investigation of IFIs in the solid organ transplant population to date (8). Per overall TRANSNET analysis, the 12-month cumulative incidence of invasive mycoses in lung and heart-lung transplant recipients was 8.6% and invasive mold infections (IMIs) accounted for 70% of all IFIs in this transplant population. This was in contrast to the heart, kidney and liver solid organ transplant populations for which 35%, 21%, and 18% of all IFIs respectively were caused by molds (8). Given the importance of IMIs in the lung transplant population, we used the TRANSNET prospective data to further describe the epidemiology of IMIs in lung transplant recipients.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted in accordance with U.S. Good Clinical Practice regulations and guidelines; human subject approval or waiver was obtained at each institution from which data was reported to TRANSNET.

Surveillance was conducted prospectively among 15 solid organ transplant centers in the United States from March 2001 through March 2006 (8). A standardized case report form was used to collect data on all cases that developed an IFI during the surveillance period, regardless of when the transplant occurred. Data collected on cases included demographic information, transplant date and type, method of diagnosis, comorbid conditions and co-infections, immunosuppressive and antifungal use, and 3-month follow-up status. An IMI was defined as proven or probable by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria (9). Demographic data, transplant information, and limited follow-up data were also collected on all patients who underwent transplantation at study sites during the surveillance period (incidence cohort). Because lung transplant patients are generally considered at higher risk for IMIs than other organ transplant recipients (8), any combination of solid organ transplants that included lung were included in this analysis (for example, a patient who was a recipient of both kidney and lung allografts). For patients who developed more than one IMI, only the first IMI was used for incidence calculations.

Statistics

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Twelve-month cumulative incidence of first IMI for lung transplant patients was estimated accounting for the competing risks of death, relapse, and re-transplantation; CI estimates were calculated using the ‘cmprsk’ package, v. 2-2-2, in R (v. 2-14-1). Bivariate statistics were calculated using student’s t-test, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the five year surveillance period, we identified 1173 lung transplant recipients under surveillance at 11 of 15 participating transplant centers, and 143 (12.2%) developed IMIs. Most patients (107, 74.8%) developed one IMI; 28 (19.5%) developed 2 IMIs, 5 (3.5%) developed 3 IMIs, and 3 (3.5%) developed 4 or more. Fifty-three (37.1%) IMIs were classified as “proven” according to EORTC/MSG criteria. The most common pathogen identified was (104; 73%); non-infections (39; 27%) included: (5; 3.5%), mucormycosis (3; 2%), and “unspecified” or “other” mold infections (31; 21.7%) (Figure 1). infections were most commonly due to (n=54), followed by (n=10), (n=9), (n=4), (n=1), unknown species (n=8), and multiple unidentified species (n=18). The 12-month CI of invasive aspergillosis (IA) and non-IA infections was 4.13% and 1.35%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Infecting mold pathogens in 143 episodes of invasive mold infections occurring in lung transplant recipients.

Figure 2.

Twelve month cumulative incidence by type of first invasive mold infection (top line invasive aspergillosis; bottom line non-aspergillosis invasive mold infection).

Median age at time of IMI diagnosis was 55 years; most patients were white (125, 87.4%) and first-time transplant recipients (134, 93.7%). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was the most common indication for transplantation (59, 41%), followed by pulmonary fibrosis (25, 17.5%) and cystic fibrosis (21, 14.7%). The majority of patients (117, 81.8%) had IMI limited to the pulmonary system; disseminated infection (8, 5.6%) and skin (5, 3.7%), combined pulmonary/sinus (3, 2%) and sinus (2, 1.4%) involvement occurred less frequently. Fungemia and bone involvement were rare, with one case of each reported. Dyspnea (84, 58.8%), cough (75, 52.5%), and increased sputum production (55, 38.5%) were the most common respiratory symptoms within the first 7 days of IMI diagnosis; less than one third of patients presented with fever (44, 30.8%). Extrapulmonary symptoms were less common, with less than 5% of IMI-infected patients experiencing central nervous system, sino-nasal, or cutaneous symptoms.

However, there were significant differences in site of involvement and presentation between IA and non-IA mold infections. Compared with IA infections (Table 1), non-IA mold infections occurred more frequently in men (65.8% vs. 44.7%, p=0.036) and presented more commonly as a cutaneous infection (14.3% vs. 0%, p<0.05) while IA was more likely to be limited to the pulmonary system (93.1% vs. 62.9% p <0.001). Patients with IA were more likely to have dyspnea (65.4% vs. 41%, p<0.01) and cough (57.7% vs. 38.5%, p<0.05) while non-IA trended to have more papular or skin nodules (15.4% vs. 0%, p=NS).

Table 1.

Characteristics of TRANSNET lung transplant patients who developed invasive mold infection

| Characteristic, n (%) | IA (n = 104) | Non-IA* (n = 39) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age in years, median (range) | 55 (20–70) | 54 (18–68) | 0.464 |

|

| |||

| Male sex | 46 (44.7) | 25 (65.8) | 0.036 |

|

| |||

| Race | 0.231 | ||

| White | 95 (95.0) | 30 (88.2) | |

| Black/African-American | 5 (5.0) | 4 (11.8) | |

|

| |||

| Number of months post-transplant to IMI diagnosis, median (range) | 10.5 (0–162) | 16 (0–83) | 0.205 |

|

| |||

| Underlying disease prompting transplant | |||

| COPD/emphysema | 41 (39.4) | 18 (46.2) | 0.467 |

| Cystic Fibrosis | 17 (16.4) | 4 (10.3) | 0.360 |

| Pulmonary Fibrosis | 19 (18.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.686 |

| Sarcoidosis | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.575 |

| Other† | 23 (22.3) | 11 (28.9) | 0.446 |

|

| |||

| Prior transplant | 7 (6.7) | 2 (5.1) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Combination transplant** | 3 (2.8) | 2 (5.1) | 0.614 |

|

| |||

| Anatomical site of IMI involvement | |||

| Pulmonary only | 95 (93.1) | 22 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Sinus only | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | 0.073 |

| Sinus and pulmonary | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| Disseminated | 4 (3.9) | 4 (11.4) | 0.214 |

| Skin | 0 (0) | 5 (14.3) | 0.001 |

| Blood only | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.273 |

| Bone | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Symptoms present within 7 days of IMI diagnosis | |||

| Dyspnea | 68 (65.4) | 16 (41.0) | 0.008 |

| Cough | 60 (57.7) | 15 (38.5) | 0.040 |

| Increased sputum production | 44 (42.3) | 11 (28.2) | 0.123 |

| Fever | 34 (32.7) | 10 (25.6) | 0.542 |

| Chest pain | 15 (14.4) | 3 (7.7) | 0.399 |

| Hemoptysis | 12 (11.5) | 2 (5.1) | 0.351 |

| Sino-nasal congestion/pain | 3 (2.9) | 5 (12.8) | 0.035 |

| Papular or nodular skin lesions | 0 (0) | 6 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Central nervous system signs/symptoms | 6 (5.8) | 2 (5.1) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Three-month mortality | 23 (22.1) | 8 (20.5) | 0.836 |

|

| |||

| IMI listed as contributing cause of death | 12 (52.2) | 4 (50) | 0.647 |

|

| |||

| Assessed at the time of IMI diagnosis | |||

|

| |||

| Renal insufficiency | 34 (32.7) | 16 (42.1) | 0.431 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 45 (43.3) | 12 (30.8) | 0.017 |

|

| |||

| Neutropenia | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Assessed within 90 days prior to IMI | |||

|

| |||

| Organ rejection | 22 (21.2) | 7 (18.0) | 0.817 |

|

| |||

| Prophylactic antifungal therapy | |||

| Amphotericin B, inhaled | 8 (7.7) | 4 (10.3) | 0.736 |

| Fluconazole | 9 (8.7) | 1 (2.6) | 0.286 |

| Itraconazole, oral | 21 (20.2) | 4 (10.3) | 0.164 |

| Itraconazole, intravenous | 2 (1.9) | 2 (5.1) | 0.300 |

| Voriconazole | 2 (1.9) | 4 (10.3) | 0.047 |

| Ketoconazole | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Empiric antifungal therapy | |||

| Amphotericin B, intravenous | 2 (1.9) | 2 (5.1) | 0.560 |

| Fluconazole | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.396 |

| Itraconazole, oral | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0.551 |

| Voriconazole | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0.551 |

| Caspofungin | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

|

| |||

| Antifungal treatment for IMI | |||

|

| |||

| Amphotericin B, intravenous | 28 (26.9) | 9 (23.1) | 0.640 |

| Amphotericin B, inhaled | 19 (18.3) | 5 (12.8) | 0.438 |

| Fluconazole | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.273 |

| Itraconazole, oral | 25 (24.0) | 7 (18.0) | 0.437 |

| Itraconazole, intravenous | 3 (2.9) | 2 (5.1) | 0.614 |

| Voriconazole | 58 (55.8) | 14 (35.9) | 0.034 |

| Caspofungin | 30 (28.9) | 6 (15.4) | 0.099 |

IA, invasive aspergillosis; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

scedosporiosis, fusariosis, mucormycosis, other mold infections, and unspecified mold infections (fungal organisms observed on histopathology but not cultured)

Kartagener’s Syndrome, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, pulmonary hypertension, Eisenmenger syndrome, and idiopathic lung failure

4 lung/heart and 1 lung/liver

The 3-month mortality for all IMI patients was 21.7%; IMI was noted to be a contributing cause of death in 52% of cases. There was no significant difference in mortality among the IA group compared with the non-IA group (22% vs 21%, p=0.84).

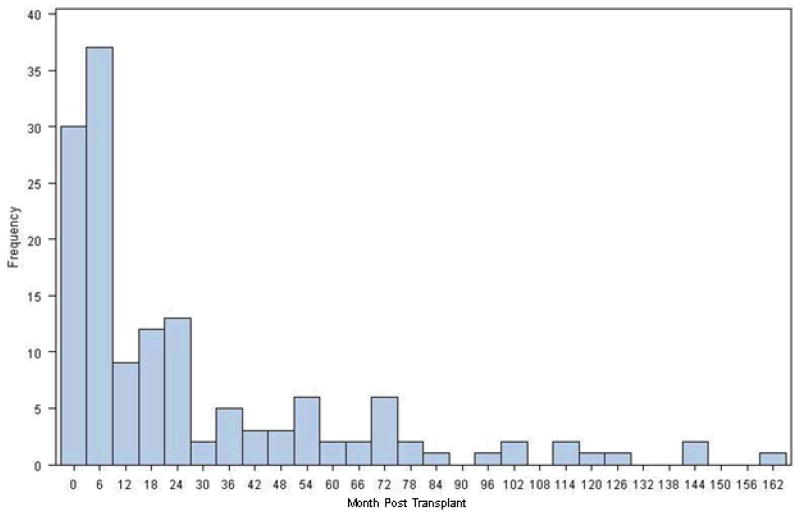

IMIs occurred a median of 11 months post-transplant (range: 0–162 months)(Figure 3). Early IMI (≤90 days) accounted for 25% of IMIs; 65% of IMIs occurred within 2 years of transplantation. Median time to IA was slightly less than non-IA IMI (10.5 months vs. 16 months respectively, p=0.2). Considerable variability in time to onset was seen among non-IA IMIs: “unspecified” mold infections (mold visualized on histopathology but not grown in culture) occurred a median of 3 months post-transplant, while infections (median 12 months post-transplant), “other” mold infections (median 16 months post-transplant), and mucormycosis (median 26 months post-transplant) occurred later.

Figure 3.

Frequency of invasive mold infection diagnosis by months post-transplant (n=143)

Discussion

This report describes the first and the largest prospective surveillance for IMI among lung transplant recipients and underscores the importance of IMIs in the lung transplant population. Notably, we confirm findings from prior retrospective epidemiologic investigations of IMI among lung transplant recipients, including: IMIs typically occur late (>90 days) in the post-transplant course, the lung as the most common anatomical site of involvement, and dyspnea and cough as the most common presenting symptoms. spp. were the most common molds isolated, comprising over 70% of all IMIs. This is also comparable to other studies which found IA to account for 63% to 69% of all IFIs among lung transplant recipients (10, 11). However, our data also confirm the importance of non-IA mold infections in this population as 30% of IMIs were caused by molds other than . While there was no significant difference in the frequency of disseminated disease in the non-IA versus IA mold groups, skin infection was more common in the non-IA IMI group, likely explained by the 26% of “other” IMIs caused by dematiaceous fungi.

IMI was associated with a high all-cause 3-month mortality of over 20% and was considered a contributor in the cause of death in over half of all patients with IMI that died. Our results are similar to those reported in 2010 by Arthurs et al, who reported 16% all-cause mortality associated with IFIs and a significant association with decreased survival (10). While these contemporary rates are lower than previously reported (7), the decrease may reflect differences in the type of IMIs studied and/or advances in recognition and treatment of IMIs over the years. Regardless, mortality still remains unacceptably high, and preventing IMIs remains a worthy goal.

When evaluating the presenting signs and symptoms of IMI, only 30% of patients experienced fever within 7 days of IMI diagnosis. This low rate of pyrexia is similar among other SOT recipients with IA (12), but is substantially lower than pyrexia rates seen among HSCT recipients, which have been reported at nearly 50% (18), as well as among critically ill immunocompetent patients with IA, which have been reported at 55–85% (13). The EORTC/MSG definitions for IFI do not utilize fever as criteria for diagnosis of IMI; our findings support this and suggest that absence of fever should not exclude IMI from the clinical differential diagnosis.

The majority of IMIs occurred after the first three months, but within the first post-lung transplant year (median 11 months). Late IMI onset was found for both IA and non-IA mold infections. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the time to onset of IA versus non-IA molds when grouped together, considerable variability was seen in time to onset among different non-IA mold infections, with a median time to onset of 26 months for mucormycosis. Thus, the majority of all IMIs tend to be late onset (>90 days post-transplant) with certain non-IA mold infections occurring very late (> 1 year) in the post-transplant course. One possible explanation for this shifting epidemiology may be the routine early use of mold-active prophylaxis in lung transplant recipients and development of infection after prophylaxis is stopped. The 2004 American Society of Transplantation (AST) guidelines recommended continuing prophylaxis after lung transplantation at least until bronchial anastomosis remodeling is complete, which takes 4 to 8 months (14). A 2006 survey of 43 international lung transplant centers found that 69% used antifungal prophylaxis during the immediate post-transplant period as the anastomosis was healing, most commonly an aerosolized formulation of amphotericin B alone or in combination with itraconazole (15). While the advent of newer triazole antifungals has altered some center’s prophylaxis strategy, more recent data demonstrates a continued heavy reliance on itraconazole and aerosolized amphotericin B and significant discontinuation rates of newer triazoles due to toxicity (16). Thus, use of mold active prophylaxis during the early post-transplant period may be influencing the timing of IMIs, resulting in late onset disease when prophylaxis is no longer routinely employed. Alternatively, the shift to later IMI may also be related to increased exposures, as patients resume normal activities of living following the transplant procedure.

Consistent with the 2009 AST guidelines (17), prevention strategies should give consideration to the known epidemiology of IMIs in this population, including the infecting pathogens, the mode of transmission/initial site of infection, and the usual timing of IMIs following lung transplantation. This approach allows prophylactic therapy to be targeted during windows of highest risk. The majority of experts agree that the historical risk for IFI is substantially high enough during the immediate post lung transplant period to warrant universal antifungal prophylaxis until the anastomosis is healed (18). Additionally, based on our data, expert opinion holds that upon completion of initial prophylaxis, patients and caregivers should be particularly vigilant in monitoring patients for late onset IMIs and avoiding environmental exposures that may lead to inoculation with these pathogens (19). Finally, prophylactic agents should be individualized based on the type of lung transplant performed (e.g. use of systemic rather than aerosolized agents in single lung transplant recipients) and therapeutic drug monitoring considered to ensure adequate absorption of orally administered triazoles (20).

In summary, IMIs, which tend to appear in the late and very late post-lung transplant period, are associated with high mortality. remains the most common mold pathogen; however, non-IA molds are also an important cause of IMIs. Appreciation of the epidemiology of IMIs and assessment of each patient’s individual risks should be used to refine prevention strategies in the lung transplant population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control [Grant No] and NIH NIAID K24 AI072522 (BDA).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Christina T. Doligalski: nothing to disclose

Benjamin Park: nothing to disclose

Kaitlin Benedict: nothing to disclose

Angela A. Cleveland: nothing to disclose

Peter G. Pappas:

John W. Baddley:

David W. Zaas: Pfizer, APT Pharmaceuticals, and Merck

Matthew T. Harris: nothing to disclose

Barbara D. Alexander: Research grants from Astellas, Pfizer, Charles River Laboratores; Advisor for Bristol Myers Squibb, bioMerieux, Astellas

Contributor Information

Christina T. Doligalski, Department of Pharmacy, Tampa General Hospital, Tampa, USA

Kaitlin Benedict, Mycotic Diseases Branch, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Angela A. Cleveland, Mycotic Diseases Branch, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA

Benjamin Park, Mycotic Diseases Branch, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Gordana Derado, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA.

Peter G. Pappas, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA

John W. Baddley, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA

David W. Zaas, Department of Medicine, Duke University Hospital, Durham, USA

Matthew T. Harris, Department of Pharmacy, Duke University Hospital, Durham, USA

Barbara D. Alexander, Departments of Medicine and Pathology, Duke University Hospital, Durham, USA

References

- 1.2011 Annual Report of the US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1994–2011. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; Rockville, MD: United Network for Organ Sharing; Richmond, VA: University Renal Research and Education Association; Ann Arbor, MI: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossi P, Farina C, Fiocchi R, Dalla Gasperina D. Prevalence and outcome of invasive fungal infections in 1963 thoracic organ transplant recipients: a multicenter retrospective study. Italian Study Group of Fungal Infections in Thoraccic Organ Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2000;70:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iversen M, Burton CM, Vand S, Skovfoged L, Carlsen J, Milman N, et al. Aspergillus infection in lung transplant patients: incidence and prognosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:879–886. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugliese F, Ruberto F, Cappannoli A, Perrella SM, Bruno K, Martelli S, et al. Incidence of fungal infections in a solid organ recipients dedicated intensive care unit. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:2005–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radack KP, Alexander BD. Prophylaxis of invasive mycoses in solid organ transplantation. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:427–34. doi: 10.1007/s11908-009-0062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavalda J, Len O, San Juan R, Aguado JM, Fortun J, Lumbreras C, et al. Risk factors for invasive aspergillosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: a case control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:52–59. doi: 10.1086/430602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solé A, Morant P, Salavert M, Pemán J, Morales P Valencia Lung Transplant Group. Aspergillus infections in lung transplant recipients: risk factors and outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, Hadley S, Kauffman CA, Freifeld A, et al. Invasive Fungal Infections among Organ Transplant Recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1101–11. doi: 10.1086/651262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1812–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthurs SK, Eid AJ, Deziel PJ, Marshall WF, Cassivi SD, Walker RC, Razonable RR. The impact of invasive fungal diseases on survival after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neofytos D, Fishman JA, Horn D, Anaissie E, Chang CH, Olyaei A, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12:220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baddley JW, Andes DR, Marr KA, Kontoyiannis DP, Alexander BD, Kauffman CA, et al. Factors associated with mortality in transplant patients with invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1559–1567. doi: 10.1086/652768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blot SI, Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, Meersseman W, Brusselaers N, et al. A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:56–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fungal infections. American Journal of Transplantation. 2004;4:110–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6135.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husain S, Zaldonis D, Kusne S, Kwak EJ, Paterson DL, McCurry KR. Variation in antifungal prophylaxis strategies in lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8:213–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neoh CF, Snell GI, Kotsimbos T, Levvey B, Morrissey CO, Slavin MA, Stewart K, Kong DC. Antifungal prophylaxis in lung transplantation--a world-wide survey. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(2):361–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh N, Husain S AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Invasive aspergillosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:S180–S191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon SM, Avery RK. Aspergillosis in lung transplantation: incidence, risk factors, and prophylactic strategies. Transpl Infect Dis. 2001;3:161–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2001.003003161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avery RK, Michaels MG AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Strategies for safe living following solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9 (Suppl 4):S252–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeiffer CD, Perfect JR, Alexander BA. Current controversies in the treatment of fungal infections. In: Safdar A, editor. Principles and Practice of Cancer Infectious Diseases (Current Clinical Oncology) New York, NY: Humana Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]