Abstract

Osteosarcoma is one of the most common pediatric cancers. Accurate imaging of osteosarcoma is important for proper clinical staging of the disease and monitoring of the tumor’s response to therapy. The MYC oncogene has been commonly implicated in the pathogenesis of human osteosarcoma. Previously, we have described a conditional transgenic mouse model of MYC-induced osteosarcoma. These tumors are highly invasive and are frequently associated with pulmonary metastases. In our model, upon MYC inactivation osteosarcomas lose their neoplastic properties, undergo proliferative arrest, and differentiate into mature bone. We reasoned that we could use our model system to develop noninvasive imaging modalities to interrogate the consequences of MYC inactivation on tumor cell biology in situ. We performed positron emission tomography (PET) combining the use of both 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) and 18F-flouride (18F) to detect metabolic activity and bone mineralization/remodeling. We found that upon MYC inactivation, tumors exhibited a slight reduction in uptake of 18FDG and a significant increase in the uptake of 18F along with associated histological changes. Thus, these cells have apparently lost their neoplastic properties based upon both examination of their histology and biologic activity. However, these tumors continue to accumulate 18FDG at levels significantly elevated compared to normal bone. Therefore, PET can be used to distinguish normal bone cells from tumors that have undergone differentiation upon oncogene inactivation. In addition, we found that 18F is a highly sensitive tracer for detection of pulmonary metastasis. Collectively, we conclude that combined modality PET/CT imaging incorporating both 18FDG and 18F is a highly sensitive means to non-invasively measure osteosarcoma growth and the therapeutic response, as well as to detect tumor cells that have undergone differentiation upon oncogene inactivation.

Keywords: MYC, osteosarcoma, PET, 18F, 18FDG, trangenic mouse model, metastasis

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the sixth most common pediatric cancer.1 The prognosis is highly dependent upon whether or not the disease has metastasized to the lungs. In patients where the disease has not metastasized, the 5-year survival is 60–80%. However, after the disease has metastasized entered the lungs, 5-year survival rates drop to 20–50%.2 Hence, early detection and precise staging of osteosarcoma is very important to predict the clinical outcome. Presently, osteosarcoma is clinically staged predominately by Computed Tomography (CT). However, while CT scans can be used to measure the presence and size of tumor masses, they cannot easily distinguish benign from malignant tissue. Positron Emission Tomography (PET), which uses radioactive tracers to measure the biological properties of tumors, has proved generally useful in distinguishing benign from malignant tumor masses.3,4

Previously, we have described a transgenic mouse model of MYC-induced osteosarcoma.5,6 In our model, the MYC oncogene is conditionally expressed under the control of the Tet-system. Tumor regression occurs through proliferative arrest, senescence and differentiation of the tumor cells into mature bone. MYC has been implicated in the pathogenesis of 40% of human osteosarcomas.7,8 Thus, our system appears to be relevant to the study of human osteosarcoma.

We reasoned that we should be able to non-invasively monitor in situ the impact of MYC inactivation in osteosarcomas on cellular proliferation and differentiation by utilizing PET imaging with specific tracers. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) is a radioactively labeled glucose analog that is taken up in cells with high metabolic activity. 18F-fluoride (18F) is incorporated into cells that are undergoing bone remodeling.9 Here we report that by combining both 18FDG and 18F, we are able to follow and characterize in situ the consequences of MYC inactivation in osteosarcomas.

Results

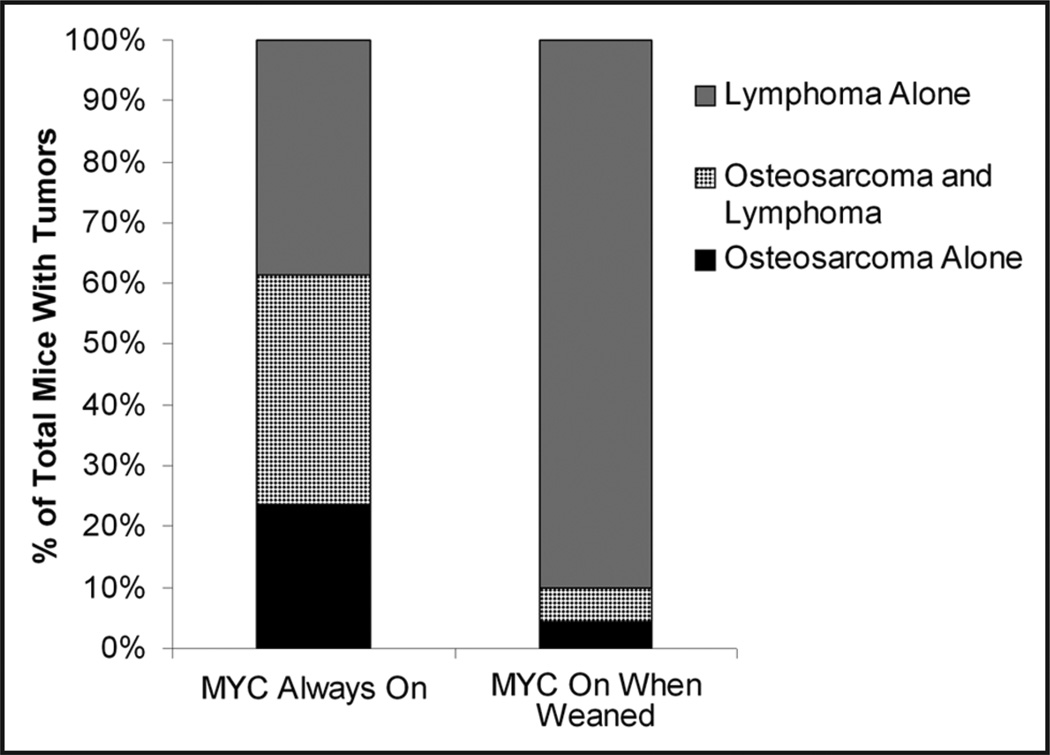

Previously, we demonstrated that we can use the Tet-system to generate conditional transgenic models of MYC-induced osteosarcomas.6,10,11 Although we formerly reported that only 1% of our transgenic mice succumbed to osteosarcoma, we now have identified sublines of these mice that develop osteosarcoma at a much higher frequency of 40%. In this cohort, over 80% of tumors presented in mice that were under 8 weeks of age. Furthermore, when MYC was constitutively expressed, 61% (65/106) developed osteosarcoma. By contrast, only 10% (7/70) of mice developed osteosarcoma when MYC was turned on after the mice were weaned (Fig. 1). In all cases, there was either gross or histological evidence of pulmonary metastasis upon post-mortem examination (Suppl. Fig. 1). The predisposition of tumors to develop in young mice and metastasize to the lung closely mimics what is observed in human osteosarcomas. Thus, we have developed a model of MYC-induced osteosarcoma that contains features of a highly metastatic tumor.

Figure 1.

Incidence of osteosarcomas in transgenic Eµ-tTA, Tet-o-MYC mice. When MYC is on from conception 24% (25/106) of mice will develop osteosarcomas, 38% (40/106) will develop both osteosarcomas and lymphomas, and 39% (41/106) will develop lymphomas alone. If MYC is activated when mice are weaned the incidence of osteosarcoma drops to a total of 10% (7/70), while the percentage of mice that will develop lymphoma alone rises to 90% (63/70).

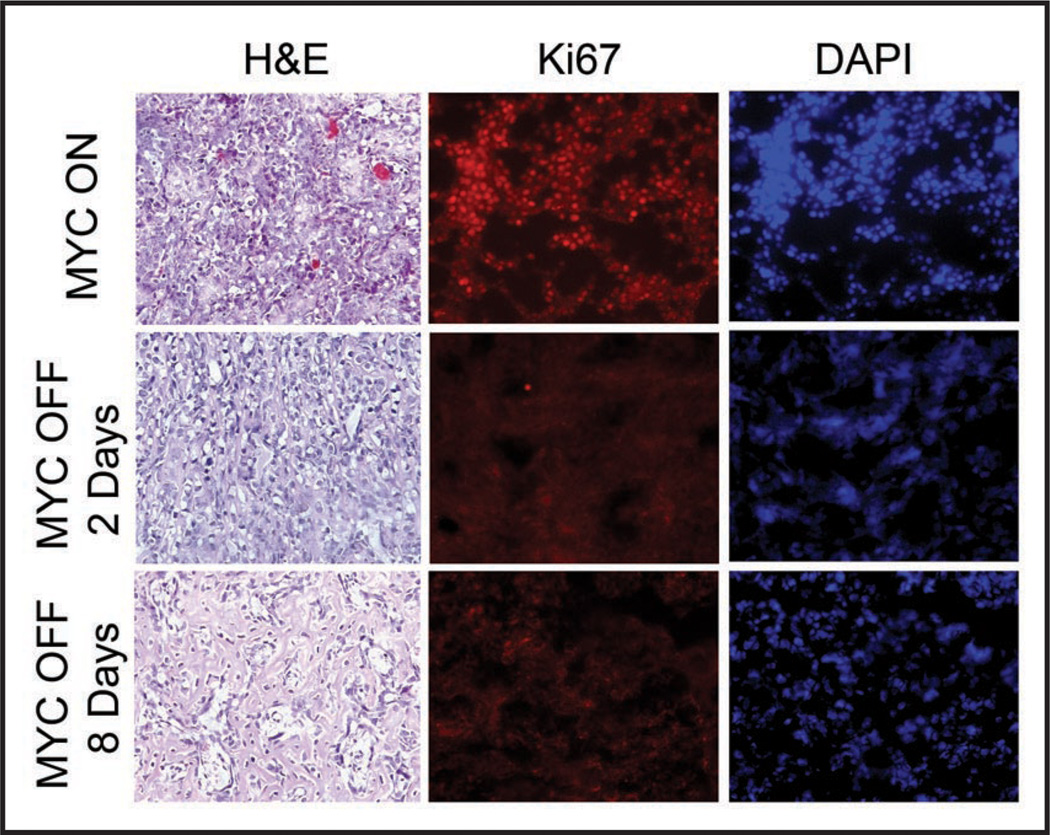

We have described that upon inactivation of MYC with doxycycline treatment, osteosarcomas lose their neoplastic properties, undergo proliferative arrest, differentiate from immature osteoblasts into mature osteocytes and exhibit features of cellular senescence.6 Histological examination of tumors revealed that upon MYC inactivation, tumor cells ceased to proliferate, as measured by Ki67 staining. Additionally, tumors showed evidence of bone formation after 2 days, and by day 8 the entire tumor mass was calcified (Fig. 2). These observations are consistent with conclusion that upon oncogene inactivation, tumors undergo differentiation and form mature bone.

Figure 2.

MYC inactivation in osteosarcoma is associated with reduced cellular proliferation and bone differentiation. Tumor cells were transplanted subcutaneously into syngeneic mice. When tumors reached a diameter of 1.0 to 1.5 cm, mice were sacrificed (MYC ON) or treated with doxycycline for either 2 or 8 days (MYC OFF). Calcification begins to appear at day 2, and by day 8 the entire tumor is calcified as assayed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Ki67 staining demonstrated that 2 days following MYC inactivation, the tumors are no longer proliferating. DAPI staining demonstrates that calcification is accompanied by a decrease in tumor cell density.

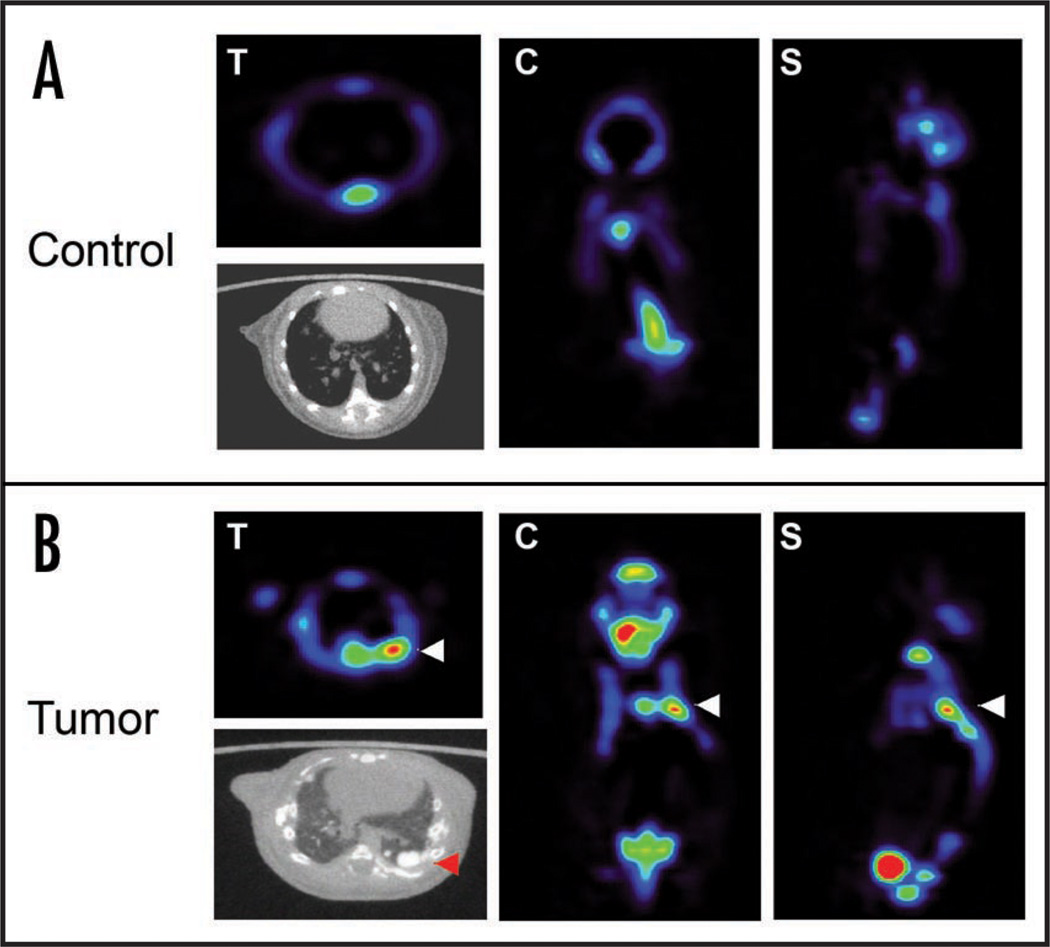

We considered that imaging with both CT and PET would be a sensitive means to detect osteosarcoma and metastatic lesions. Indeed, we were able to detect by small animalPET/CT primary tumors and metastatic lesions in transgenic mice (Fig. 3). Gross and histological examination of the tumors confirmed the presence of lung metastases as detected by CT and PET. Therefore,18F is a sensitive tracer for identifying both primary tumors as well as pulmonary metastases.

Figure 3.

18F can be used in microPET to detect osteosarcoma. (A) 18F scan of a syngeneic mouse without osteosarcoma. (B) 18F scan of an Eµ-tTA, Tet-O MYC mouse detects an osteosarcoma lung metastasis (as indicated with white arrow). A CT scan confirms the calcification of the tumor mass (red arrow) T = transverse, C = coronal, S = sagittal.

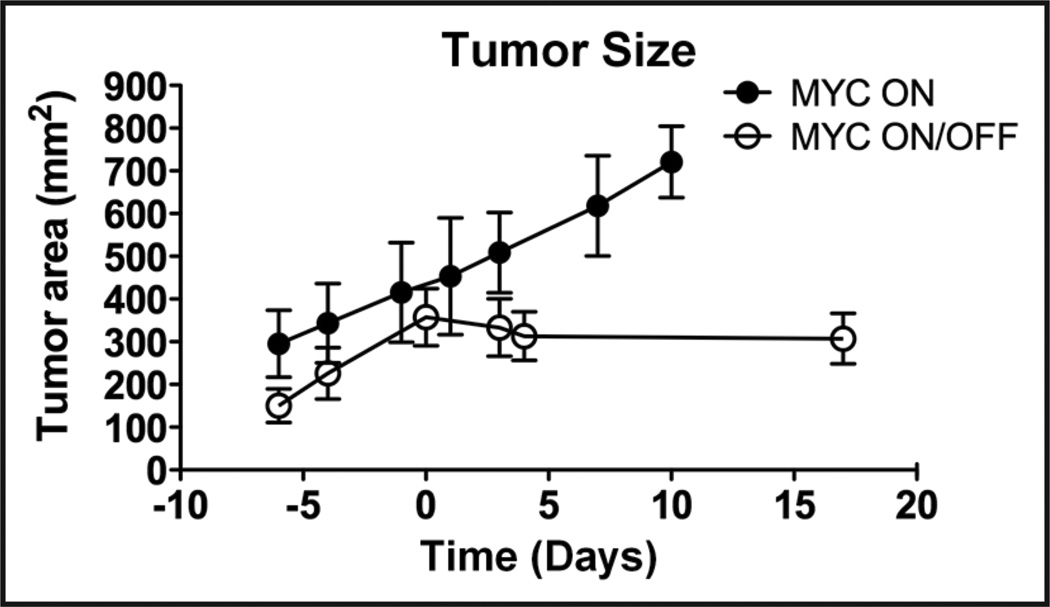

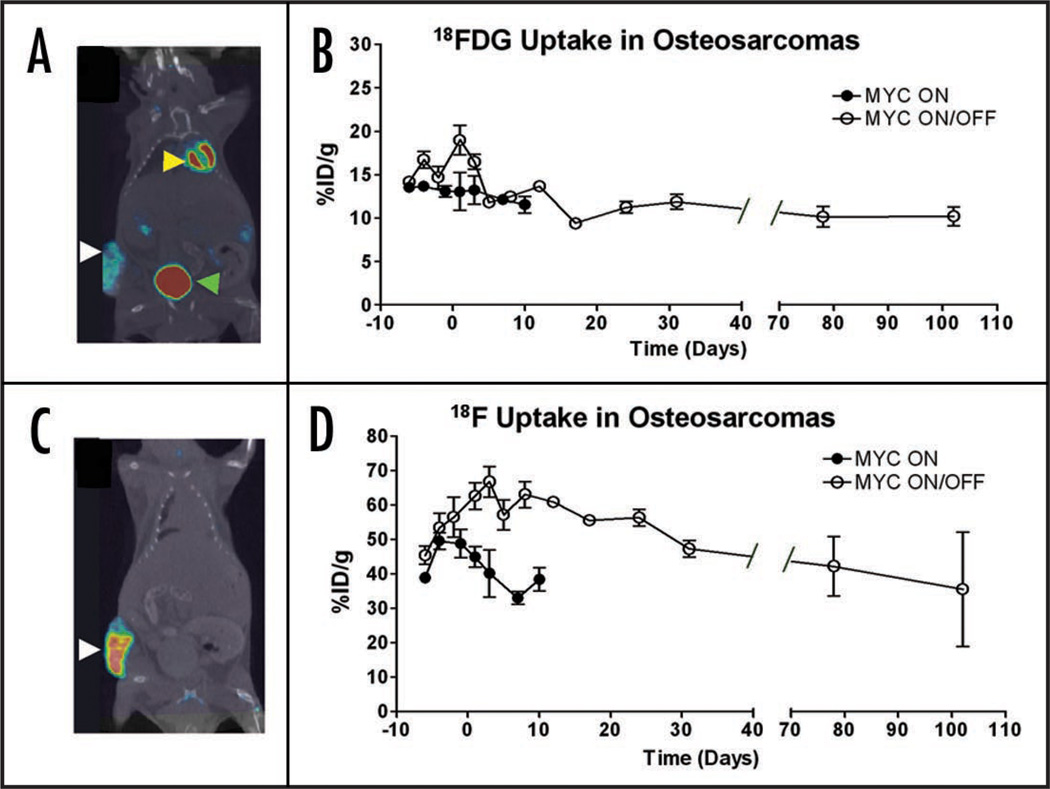

In order to to non-invasively monitor the consequences of MYC inactivation, we utilized PET scans incorporating both 18FDG to measure glucose metabolism, and 18F to measure bone mineralization. PET scans were performed on subcutaneous osteosarcomas every 3–4 days for 4 weeks. Prior to MYC inactivation, tumors were scanned for baseline measurements. Tumor size was measured by calipers and CT. As expected, within one week of MYC inactivation, tumors ceased to grow, whereas when MYC remained on, tumors continued to proliferate (Fig. 4). The level of uptake by 18FDG PET when MYC was constitutively on was consistently between 14% ID/g. Notably, when tumor size reached a certain threshold, the masses exhibited reduced tracer uptake, which correlated to the gross observation upon necropsy that the tumors had areas of necrosis (Fig. 5B, black circles). When MYC was shut off, 18FDG activity initially rose and then dropped within 5 days to 12% ID/g. However this change was not statistically significant (p = 0.8) indicating that after differentiation tumors remained metabolically active. Importantly, 18FDG uptake even after prolonged MYC inactivation was persistently higher (12% ID/g) than observed in normal bone tissue (2.5% ID/g). These results suggest that although osteosarcoma cells no longer exhibited neoplastic properties after MYC inactivation, tumors continued to exhibit increased cellular metabolism, which distinguished them from normal tissue.

Figure 4.

MYC inactivation results in neither an increase nor a decrease in tumor size. An osteosarcoma cell line (1325) was injected subcutaneously into syngeneic hosts. Following MYC inactivation (Day 0) tumors stop growing, but do not reduce in size. Tumors where MYC is on continued to grow. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Figure 5.

MYC inactivation causes a slight decrease in 18FDG uptake and a significant increase in 18F uptake in osteosarcomas. An osteosarcoma cell line (1325) was injected subcutaneously into syngeneic hosts. MYC was inactivated at day 0. (A) CT scan (black and white) co-registered with an 18FDG microPET scan (color intensity indicative of tracer uptake). 18FDG was taken up in the tumor (white arrow) as well as the heart (yellow arrow) and excreted into the bladder (green arrow). (B) 18FDG uptake following MYC inactivation (Day 0) was measured. 18FDG activity spikes and then plateaus following MYC inactivation. 18FDG levels do not increase when tumors grow out in the presence of doxycycline (Day 102). In tumors where MYC was constantly on, levels of 18FDG uptake did not change significantly. (C) CT scan (black and white) co-registered with an 18F PET scan (color intensity indicative of 18F uptake). The tumor readily took up the tracer (white arrow). (D) Quantification of 18F uptake following MYC inactivation. 18F activity remains higher than in controls (MYC ON) following MYC inactivation, and then gradually decreases. At approximately 30 days following MYC inactivation, tumor uptake levels were consistent with levels prior to inactivation. 18F levels do not increase when there was evidence of new tumor growth in the presence of doxycycline (Day 102). In tumors where MYC was not inactivated, 18F uptake rises slightly and then drops as tumors become necrotic. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Next, 18F uptake was measured in osteosarcomas before and after MYC inactivation. In tumors where MYC was constitutively on, 18F incorporation increased until it reached a maximum of 50% ID/g. Notably, levels of 18F eventually dropped to 40% ID/g, which most likely can be attributed to tumor necrosis (Fig. 5D). In the first three days following MYC inactivation, 18F uptake increased from 50% ID/g to 67% ID/g and then subsequently dropped to 48% ID/g. After MYC had been inactivated, tumors exhibited a statistically significant increase in tracer incorporation (p = 0.01). We noted that the transient increase in 18F activity was not due to a change in tumor size. Instead, appears to be strongly correlated with the rapid increase in calcification and bone differentiation that are evident upon histological examination of tumors following two days of MYC inactivation (Fig. 2).

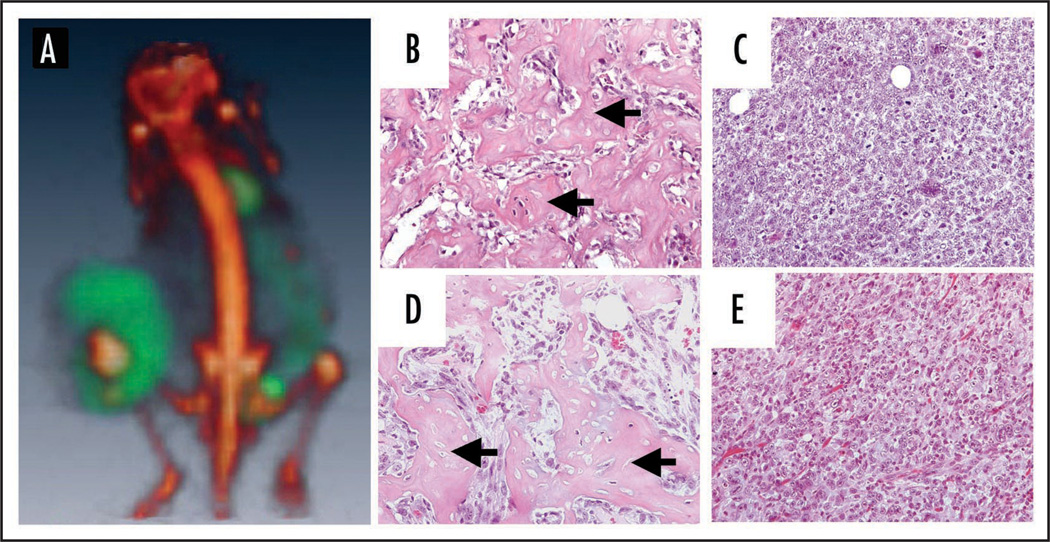

After prolonged MYC inactivation (>80 days), many tumors (5 out of 10) had new areas of tumor growth. We performed PET analysis and found the tumors were comprised of two masses that had different PET tracer uptake profiles. The original tumor mass, which was present prior to MYC inactivation, was positive for 18F and had very low levels of 18FDG. This is in marked contrast to the new tumor growth, which was positive for 18FDG but negative for 18F (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, the uptake of 18FDG in the new tumor growth was consistent with levels found in tumors where MYC was off (11% ID/g). Upon histological examination of the tumors that persisted despite MYC inactivation, it was confirmed that there was no evidence for bone formation or calcification in the new tumor growth (Fig. 6B–E). Therefore, by incorporating PET scans using both 18F and 18FDG tracers, we are able to non-invasively monitor osteosarcoma growth and regression and changes in biological activity associated with oncogene inactivation.

Figure 6.

Prolonged MYC inactivation is associated with the loss of bone formation and 18F uptake in tumors. (A) 18F and 18FDG scans of a tumor that has grown despite continuous MYC inactivation. 18F (red) and 18FDG (green) scans coregistered demonstrate that the portion of the tumor that grew while MYC was inactivated envelops the original calcified tumor. Image confirms that 18F (red) and 18FDG (green) regions do not coregister. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of two different tumors that grew despite MYC inactivation. (B and D) The original portion of the tumor contains dense patches of calcification (Black arrows) (C and E) The portion of the tumor that has grown out despite continuous MYC inactivation does not contain any osteoid. Images are from two different tumors and representative of what was observed in 5 different relapse tumors.

Discussion

We found that PET imaging incorporating both 18FDG and 18F tracers can be generally used as a highly sensitive modality to non-invasively monitor osteosarcoma metabolic activity and bone differentiation and detect the presence of pulmonary metastases. Importantly, we found that PET imaging could identify osteosarcoma cells that had morphologically and histologically differentiated into normal-appearing bone. We found that upon MYC inactivation, tumors that otherwise appear to have differentiated into normal bone continue to avidly uptake 18FDG at levels much higher than normal bone. Hence, the normal morphological appearance of the tumor cells upon MYC inactivation is misleading since these cells continue to metabolically behave like tumor cells. Only through PET imaging were we able to detect this behavior in tumor cells.

Also, we found that after prolonged MYC inactivation many of the tumors resumed growth. Yet these recurrent tumors no longer exhibited 18F uptake, suggesting that they no longer were capable of undergoing mineralization. Moreover, they exhibited slightly reduced levels of 18FDG uptake compared with tumors prior to MYC inactivation, but uptake was still significantly elevated over normal bone. Thus, our results exemplify how PET imaging uncovers biological features of the malignant progression of osteosarcoma in situ which are not readily observable through gross and microscopic observation.

PET imaging with 18FDG is already commonly utilized but only limited studies report the use of 18F in humans.12–14 Our results are consistent with several reports that suggest that 18F may be a more sensitive and specific tracer for osteosarcomas.15–17 Our results further suggest that the combination of both 18F and 18FDG may be useful in staging and monitoring the therapeutic response of patients with osteosarcoma. Finally, our results suggest that PET imaging can be used as a powerful modality to identify the malignant progression of osteosarcoma associated with a change in the ability of these cells to undergo bone differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic animals

Tet-o-MYC transgenic mice have been described previously.6,11

Subcutaneous tumor generation

Syngeneic (FVB) mice where injected subcutaneously with 5 × 106 early passage 1325 osteosarcoma cells suspended in 200 µl of PBS. Mice were monitored and when tumors reached 1–1.5 cm in diameter MYC was inactivated.

MYC inactivation in vivo

Mice were initially injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 100 µg of doxycycline. Doxycycline was also added to their drinking water at a concentration of 100 µg/ml, changed once per week.

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours and then transferred to 70% ethanol until being embedded in paraffin. 5 µM sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard procedures. Frozen 10 µM sections of tissue were fixed in acetone and used for Ki67 staining and DAPI staining.18

PET imaging

The Radiochemistry Facility at Stanford University produced tracers using a GE PETtrace cyclotron. 100 µCi of 18F was injected intraperotoneally (IP) into mice, and 90 minutes later mice were imaged for 5 minutes using a static scan. After 6 hours of fasting, 300 µCi of 18FDG was injected IP, and 90 minutes later mice were imaged for 5 minutes. Although mice were imaged on the same day, at least 3 half lives passed between 18F injection and 18FDG imaging, which allowed for the decay of the 18F tracer. Mice were imaged at the Small Animal Imaging Facility at Stanford University on either a R4 microPET scanner (Concorde Microsystems) or an eXplore Vista PET scanner (GE Health Care). The images were reconstructed by a 2-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximum (OSEM) algorithm. A total of 17 mice were imaged, 7 of which were controls.

Generation of ROI

Imaging files were analyzed with AMIDE.19 ROIs were drawn on decay-corrected, whole-body images by using the 3D isocontour function and setting the threshold to 25% above minimum for 18F and to 10% above minimum for 18FDG. These values were chosen because they yielded ROIs of similar size to the estimated total tumor volume when MYC was on. The mean activity was calculated from all voxels in the ROI by AMIDE directly after defining the calibration constant and the decay corrected injected dose. Uptake of tracers was measured in percent uptake of injected dose per gram of tissue in the ROI (%ID/g). In addition to PET scans, tumor size was measured with either calipers or from CT scans.

Corrected 18FDG uptake

Both 18F and 18FDG uptake in the tumor (as determined from the ROI) was converted into raw activity, by using the formula below. Decayed 18F activity within the ROI was subtracted from 18FDG activity and then 18FDG activity was reconverted into %ID/g:

is the tissue density, assumed to be approximately 1 cc/g.

CT is the output generated from the ROI, and D(n), is the injected dose at the time of imaging.

Statistics

Two tailed unpaired t-tests were performed on the data using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software) to determine significance between the two groups.

Coregistration of PET scans

Coregistration of PET scans was performed by using the coregistration function in AMIRA (Mercury Computer Systems).

CT scans

CT scans were performed on a GE Medical Systems eXplore RS MicroCT System. Mice were scanned in three bed positions for seven minutes each at 97 µm resolution. Whole mouse CT scans were also performed on a Gamma Medica-Ideas microSPECT/CT at a 170 µm resolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Felsher Laboratory for their helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank Timothy Doyle and Shay Keren in the Small Animal Imaging Facility at Stanford for their invaluable guidance and support with both the animal imaging as well as the analysis software. This work was supported by the NIH ROI CA105102, CA89305, ICMIC CAA114747 (D.W.F), Lymphoma Leukemia Society (D.W.F), Burroughs Wellcome (D.W.F), Damon Runyon (D.W.F) and the NIH Neonatology Training grant (C.A).

Footnotes

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/ArvanitisCBT7-12-Sup.pdf

References

- 1. http://www.cancer.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruland OS, Pihl A. On the current management of osteosarcoma. A critical evaluation and a proposal for a modified treatment strategy. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1725–1731. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Hohenberger P, Strobel P, Marx A, Strauss LG. A recent application of fluoro-18-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography, treatment monitoring with a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor: an example of a patient with a desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Hell J Nucl Med. 2007;10:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar R, Chauhan A, Kesav Vellimana A, Chawla M. Role of PET/PET-CT in the management of sarcomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:1241–1250. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.8.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu CH, van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Fan AC, Bachireddy P, Felsher DW. Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13028–13033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701953104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain M, Arvanitis C, Chu K, Dewey W, Leonhardt E, Trinh M, Sundberg CD, Bishop JM, Felsher DW. Sustained loss of a neoplastic phenotype by brief inactivation of MYC. Science. 2002;297:102–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1071489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturm SA, Strauss PG, Adolph S, Hameister H, Erfle V. Amplification and rearrangement of c-myc in radiation-induced murine osteosarcomas. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4146–4153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamberi G, Benassi MS, Bohling T, Ragazzini P, Molendini L, Sollazzo MR, Pompetti F, Merli M, Magagnoli G, Balladelli A, Picci P. C-myc and c-fos in human osteosarcoma: prognostic value of mRNA and protein expression. Oncology. 1998;55:556–563. doi: 10.1159/000011912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ell PJ. The contribution of PET/CT to improved patient management. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:32–36. doi: 10.1259/bjr/18454286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kistner A, Gossen M, Zimmermann F, Jerecic J, Ullmer C, Lubbert H, Bujard H. Doxycycline-mediated quantitative and tissue-specific control of gene expression in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10933–10938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsher DW, Bishop JM. Reversible tumorigenesis by MYC in hematopoietic lineages. Mol Cell. 1999;4:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse N, Hoh C, Hawkins R, Phelps M, Glaspy J. Positron emission tomography diagnosis of pulmonary metastases in osteogenic sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994;17:22–25. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoh CK, Hawkins RA, Dahlbom M, Glaspy JA, Seeger LL, Choi Y, Schiepers CW, Huang SC, Satyamurthy N, Barrio JR, et al. Whole body skeletal imaging with [18F]fluoride ion and PET. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner W, Bohuslavizki KH, Eary JF. PET imaging of osteosarcoma. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schirrmeister H, Guhlmann A, Kotzerke J, Santjohanser C, Kuhn T, Kreienberg R, Messer P, Nussle K, Elsner K, Glatting G, Trager H, Neumaier B, Diederichs C, Reske SN. Early detection and accurate description of extent of metastatic bone disease in breast cancer with fluoride ion and positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2381–2389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schirrmeister H, Guhlmann A, Elsner K, Kotzerke J, Glatting G, Rentschler M, Neumaier B, Trager H, Nussle K, Reske SN. Sensitivity in detecting osseous lesions depends on anatomic localization: planar bone scintigraphy versus 18F PET. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1623–1629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schirrmeister H, Glatting G, Hetzel J, Nussle K, Arslandemir C, Buck AK, Dziuk K, Gabelmann A, Reske SN, Hetzel M. Prospective evaluation of the clinical value of planar bone scans, SPECT, and (18)F-labeled NaF PET in newly diagnosed lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1800–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beer S, Zetterberg A, Ihrie RA, McTaggart RA, Yang Q, Bradon N, Arvanitis C, Attardi LD, Feng S, Ruebner B, Cardiff RD, Felsher DW. Developmental Context Determines Latency of MYC-Induced Tumorigenesis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loening AM, Gambhir SS. AMIDE: a free software tool for multimodality medical image analysis. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:131–137. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.