Summary

Fishes are wonderfully diverse. This variety is a result of the ability of ray-finned fishes to adapt to a wide range of environments, and has made them more specious than the rest of vertebrates combined. With such diversity it is easy to dismiss comparisons between distantly related fishes in efforts to understand the biology of a particular fish species. However, shared ancestry and the conservation of developmental mechanisms, morphological features and physiology provide the ability to use comparative analyses between different organisms to understand mechanisms of development and physiology. The use of species that are amenable to experimental investigation provides tools to approach questions that would not be feasible in other ‘non-model’ organisms. For example, the use of small teleost fishes such as zebrafish and medaka has been powerful for analysis of gene function and mechanisms of disease in humans, including skeletal diseases. However, use of these fish to aid in understanding variation and disease in other fishes has been largely unexplored. This is especially evident in aquaculture research. Here we highlight the utility of these small laboratory fishes to study genetic and developmental factors that underlie skeletal malformations that occur under farming conditions. We highlight several areas in which model species can serve as a resource for identifying the causes of variation in economically important fish species as well as to assess strategies to alleviate the expression of the variant phenotypes in farmed fish. We focus on genetic causes of skeletal deformities in the zebrafish and medaka that closely resemble phenotypes observed both in farmed as well as natural populations of fishes.

Introduction

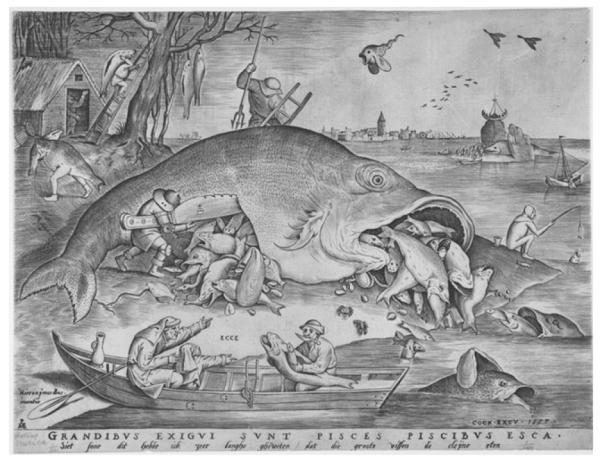

The use of experimental model organisms as a means to address function in other, often distantly related species has allowed informative analysis of the conservation as well as diversity of processes that regulate development, morphology, physiology and behaviour. One of the major unanticipated discoveries from early work in developmental genetics is the conservation of ‘core’ developmental genes and mechanisms between divergent taxa. Although variation exists within developmental networks among species, the core functions of these networks are often conserved, even across phyla. This conservation of essential developmental networks permits the study of genetic function between even distantly related organisms. Thus, the foundation of diversity lies within the use of conserved developmental and physiological mechanisms resulting from shared ancestry (Fig. 1). The use of comparative analyses is essential to uncover the principles that underlie the evolution of development and physiology. Moreover, comparative approaches are fundamental to biomedicine as they permit an analysis of developmental mechanisms as well as an assessment of potential therapeutic strategies in models of human disease.

Fig. 1.

Uncovering the fish within. Lithograph depicting themes of food chain dynamics in which the artist portrays an ordered hierarchy of fishes as underlying the constitution of fish. This theme appears associated with the bounty of fishes and the diversity of forms (even within humans as represented in the fish-man, top left). Big Fish Eat Little Fish, 1557 Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Netherlandish, d. 1569); Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917 (17.3.859). http://www.metmuseum.org

Certain experimentally amenable species have been used to facilitate analysis in groups that share homologous structures. Within vertebrates, two small aquarium fish, the zebrafish and medaka, have been the subject of intense study in the last 30 years to facilitate research in the regulation of development and physiology of vertebrates. Both fish share the ease of husbandry in a laboratory setting and ability to house large numbers of individuals at low cost (Porazinski et al., 2011; Lawrence et al., 2012). They are amenable to experimental procedures that are not applicable to farmed fish, such as chemical mutagenesis and forward genetic screens in which the isolation of mutants with altered phenotype permits a formal assessment of gene function. Additionally, the ease of transgenesis in these fishes facilitates analysis of gene regulation supporting a systematic analysis of the action and regulation of genes and particular genetic variants. Furthermore, recent genome editing methods such as Crispr/CAS and TALEN endonucleases allow for specific editing of genes (Bedell et al., 2012; Cade et al., 2012; Ansai et al., 2013, 2014; Chang et al., 2013; Hruscha et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Jao et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2013; Zu et al., 2013; Sung et al., 2014). Because of the accessibility of zebrafish and medaka eggs for manipulation as well as their short generation time, these techniques provide the ability to specifically alter individual genes to assess function of specific allelic variants.

An unlikely paradigm: fish models of human disease

The phenotypes that arise as result of genetic changes uncover the essential functions of genes during vertebrate development. By comparing the phenotypes identified in model species to similar processes during human development, these findings can elucidate the genes and mechanisms underlying disease. Such a comparison uses similarity between phenotypes, or phenocopy, as a means to identify parallel developmental and genetic mechanisms. Even though the zebrafish by nature of its phylogenetic history does not allow a comparison of the development of certain organs or processes (e.g. mammary gland, hair, lungs), the interrogation of zebrafish as a model for human disease has provided specific research models for many diseases including ciliopathies (Swanhart et al., 2011), myopathies (Gibbs et al., 2013), cancer (Liu and Leach, 2011; White et al., 2013), blood disorders (Jing and Zon, 2011), and diseases affecting craniofacial development (Eberhart et al., 2008; Swartz et al., 2011), cardiovascular function (Dahme et al., 2009), and behaviour (Sison et al., 2006; Norton and Bally-Cuif, 2010; Clark et al., 2011; Gerlai, 2012; Bailey et al., 2013).

Because of the experimental accessibility and large numbers of offspring stemming from a single cross, zebrafish and medaka provide an experimental capability to analyze mechanisms underlying disease states. One area of research has centered on skeletogenesis and the causes of skull malformations, osteoporosis, defects of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, verbal fusion, and pathological ectopic ossification Bensimon-Brito et al., 2012a,b; Cooper et al., 2013; Kaplan et al., 2012; To et al., 2012; Vanoevelen et al., 2011; Willems et al., 2012; Gibbs et al., 2013; Fiaz et al., 2014). Given an available disease model in a fish, the altered developmental and physiological mechanisms underlying the observed pathology can be investigated and potential therapeutic strategies can then be tested for efficacy. The success of these small laboratory fishes in biomedical research is evident in their prevalence in the scientific literature (at date of publication there were 1559 citations ‘zebrafish human disease’ and ‘medaka human disease’ in Pubmed) as well as the organization of large publicly funded consortiums to further the use of the fish in biomedical research (e.g. www.zf-models.org, zf-health http://zf-health.org/; EUFishBioMed (Strahle et al., 2012), ZF-cancer (Snaar-Jagalska, 2009).

Fish as a model for other fishes

Whereas the zebrafish and medaka are frequently used to test gene function and developmental mechanisms underlying human disease, the utility of these small laboratory fishes as a model for variation observed in other fishes has not received similar attention. While two teleost fish can be as evolutionary distant as birds and humans, even fishes as evolutionary distant from each other as the zebrafish and medaka share a more recent common ancestor [about 200 million years ago (mya)] with each other than they do with humans (400 mya). Thus, these small laboratory fish are primed to provide useful experimental models to investigate causes of morphological and physiological variation in other fishes. Previous studies capitalized on the zebrafish to assess development and variation in pigment pattern (Quigley et al., 2005; Salzburger et al., 2007; Kondo et al., 2009b), shape and formation of the jaw (Albertson et al., 2005), as well as scalation (Rohner et al., 2009) of other teleosts. Discovering the causes of diversity among fishes is important to understand the evolution of form, physiology, and behaviour. In addition, ray-finned fishes are becoming a key component to the future of human health, as fish are a major component of our diet as a source of protein and key fatty acids (Beveridge et al., 2013). Aquaculture is a growing industry, comprising up to 40% of all ‘fish’ used as food (FAO, 2012). The role of aquaculture in food production is projected to increase as demand grows and catch from natural populations decreases. Given the increasing demand for fish in the world’s diet, it is clear that a productive aquaculture as well as protection and recovery of wild fish stocks are essential for maintaining our current and future health (Thurstan et al., 2010; Beveridge et al., 2013). In rearing of fishes in hatcheries, establishing ideal conditions for rearing and breeding that maximize growth while minimizing disease and teratology are essential areas of further research as they significantly affect overall yield, efficiency, and health of the fish (Boglione et al., 2013a,b). The limited number of studies that use the zebrafish and medaka to dissect mechanisms of development and physiology within other fish species reveals a failure to capitalize on these models to understand the genetic basis of variation and disease in fishes. This perspective argues for the potential of zebrafish and medaka as research models to define the genetic regulation of development and causes of disease relevant to variation observed in nature and during intensive breeding programs of aquaculture. We focus here on causes of skeletal deformities observed in aquaculture as this represents a major concern affecting both the health of fish and production efficiency.

Fish as a genomic and genetic montage

The great variation in teleost fishes is in part due to the genetic diversity within and between species. Unlike mammalian genomes, teleost genomes have undergone at least one additional whole-genome duplication (WGD) compared to tetrapods – in some cases many times over (e.g. salmon, carps, barbs, sturgeon). Recently duplicated genes, or paralogues, will be redundant in function and may be lost overtime due to drift. However, paralogues are retained if they diversify in function by parsing existing functions (sub-functionalization) or by generation of new functions (neo-functionalization) (Force et al., 1999). Sub-functionalization can dissociate existing constraints on gene function that may limit change, thus allowing for diversification of genes having essential functions. Neo-functionalization can lead to an increase in potential for variation as the new paralogue having a pre-existing function is active in novel developmental contexts while retaining the original function of the gene.

The increase in the number of gene family members due to duplication can also allow buffering against the effects of mutation. For example, tetrasomic segregation (the inheritance of paired homeologous chromosomes in polyploids) can increase the number of alleles at particular loci and reduce effects of de novo mutation; in parallel to buffering by increased alleles, mutation load will be heightened due to decreased expression of variant alleles in polyploid fish lineages (Comai, 2005). Residual tetrasomic segregation is thought to persist in polyploid lineages of salmon and trout (Allendorf and Thorgaard, 1984; Allendorf and Danzmann, 1997) whereas the common carp is essentially diplosomic (Zhang et al., 2008). In the case of homologues that segregate independently after WGD (diploidization), sub-functionalization of gene duplicates can maintain robustness to mutation if the duplicates retain function at particular stages of development (e.g. Rohner et al., 2009) or the other copy can be co-opted in cases of altered activity of the other paralogue or gene family member (e.g. Lee et al., 1992; Mulligan and Jacks, 1998). Thus, through genome duplication and paralogue diversification, increases in genetic diversity may increase potential for variation as well as the capacity to buffer genetic variance within populations. In this context, it is interesting to note that several commercially successful fish species have large complex genomes stemming from whole genome duplication events (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genome size and chromosome number of selected fish used in laboratory studies compared with aquaculture as well as wild-caught marine species. Taxonomic order assignment according to Greenwood et al. (1966)

| Genus species | Common name | aHaploid Chr no. | aC value; (Gb)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish Commonly Used in Laboratories | |||

| Cypriniformes | |||

| Danio rerio | Zebrafish | 25 | 1.8; (1.6) |

| Atheriniformes | |||

| Oryzias latipes | Medaka | 24 | 0.75; (0.8) |

| Aquaculture | |||

| Acipenseriformes | |||

| Acipenser sp. | Sturgeon | 58–125 (250)c | 1.6–7.2 |

| Salmoniformes | |||

| Salmo salar | Atlantic Salmon | 30c | 3.1 |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | Rainbow trout | 30c | 2.6 |

| Cypriniformes | |||

| Carrassius auratus | Crucian carp | 50c | 2.14 |

| Cyrpinus carpio | Common carp | 50c | 1.7 |

| Aristichthys nobilis | Big head carp | 24 | 1.05 |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | Grass carp | 24 | 1.0 |

| Siluriformes | |||

| HaIctalurus punctatus | Channel catfish | 28 | 1 |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Striped Catfish | 30 | |

| Perciformes | |||

| Dentex dentex | Common dentex | 24 | 1 |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Nile Tilapia | 22 | 1.4 |

| Solea solea | Common sole | 22 | 0.73 |

| Pseudopleuronectes americanus | Winter flounder | 24 | 0.7 |

| Wild Marine Species | |||

| Perciformes | |||

| Mugil curema | White mullet | 24 | 0.69 |

| Gadus morhua | Atlantic cod | 23 | 0.4–0.9; (0.9) |

| Anoplopoma fimbria | Sablefish | 24 | 0.7–0.8 |

| Thunnus thynnus | Northern bluefin tuna | ND | 0.8 |

| Katsuwonus pelamis | Skipjack tuna | 24 | 1 |

A fish among fishes

Given the genetic and morphological diversity within fishes it is easy to conclude that comparative analysis will be most informative if performed among or within genera. However, because of the conservation of developmental mechanisms due to shared ancestry, a comparison of gene function and developmental mechanisms among even distantly related species can be very powerful to refine knowledge of the mechanisms underlying particular phenotypes and to provide experimental means to test hypotheses. The zebrafish and medaka are poised for use in such analysis. Each of these fish is a representative of one of the two major lineages within teleosts that diverged about 110–160 million years ago (Wittbrodt et al., 2002). Because of the evolutionary distance between these two model fish, the effect of particular genetic change can expose unique regulation that would not be garnered by analysis of one species alone. As zebrafish and medaka are members of the separate clades Ostariophysi and the Acanthamorphi, respectively, these fish can serve as local phylogenetic ‘nodes’ in which to ground comparison to other fishes within these lineages.

Experimental approaches to probe the genetic causes of phenotypes and thus understand development and physiology are hampered in many fish species by an increase of genetic complexity; the functional consequence of mutations by chemical mutagenesis or by reverse genetic tools can be more easily identified when redundancy in gene function is minimized. Importantly, both zebrafish and medaka are diploid with a relatively small number of chromosomes (haploid n = 24 and 25, respectively, Table 1). Once function of a particular gene has been defined in medaka or zebrafish, the orthologous genes can then be analyzed in other species for their role in causing a phenotype of interest. Recent advances in genomic engineering techniques permit the analysis of gene function in fish of any species as long as eggs are accessible e.g. oviparous. These powerful techniques allow us to directly test hypotheses concerning gene function in development or physiology in the target species of interest. However, given the generation time and space needed to adequately screen for phenotypes most species of commercial importance are difficult to use in a broad systematic framework.

Systematic genetic analysis of late developmental events

The zebrafish and medaka were chosen as laboratory models for attributes that support high throughput genetics and real time analysis of development. Chemical mutagenesis screens have been quite effective in defining the genetic regulation of development and physiology through the identification of specific mutants resulting from random mutation by treatment with N, N-diethyl nitrosourea (ENU) (Patton and Zon, 2001). Importantly, in mutagenesis screens environmental variables such as light cycle, temperature, water quality, density, and feeding are controlled thus limiting variance that might obscure identification of the genetic control of phenotype. Large-scale screens have been carried out in both zebrafish and medaka for mutations affecting early development to find genes essential for development (Driever et al., 1996; Haffter et al., 1996b; Loosli et al., 2000; Furutani-Seiki et al., 2004). As a consequence of their phenotypic effect, many of these mutations are lethal early in life with only a small percentage leading to phenotypes in adults (Haffter et al., 1996b). Identification of the genes altered in these adult viable mutants has shown that the similar genetic processes cause morphological variation in other vertebrates including human disease (Lamason et al., 2005; Harris et al., 2008; Asharani et al., 2012).

In previous work, we have argued for the potential of mutagenesis screens focused on postembryonic development, looking at the genetic regulation of adult form as a means of uncovering important developmental processes involved in both variation within populations as well as in evolution (Harris, 2012). Given the necessity of many genes during early development, one would predict that only a small subset of genetic alterations can persist and lead to adult viable morphological change; this constraint on potential genetic variants would shape the type of mutations that could be identified. It follows that if developmental regulation is conserved among species, this constraint would permit predictive analysis of gene function between species and the genetic and/or developmental causes of phenotypic variation.

Through a forward genetic analysis of late skeletogenic phenotypes, we were able to identify phenotypes in the zebrafish that resemble skeletal forms seen in natural populations of other fishes (Harris et al., 2008; Rohner et al., 2009). In one example, identification of the gene underlying the phenotype in the zebrafish allowed for a direct comparison with phenotypes observed in the carp revealing that the orthologues of the same gene were responsible for the altered skeletal phenotype seen in both species (Rohner et al., 2009). Similarly, mutants of the ectodysplasin signaling pathway were identified and revealed the role of this pathway in the variation in dermal skeletal derivatives in the zebrafish (Harris et al., 2008) – a pathway also known to regulate variation of dermal skeletal variation in stickleback populations (Colosimo et al., 2005) and variation in human integumentary appendages (Sabeti et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2013). Thus, even in the case of evolutionarily distant comparisons, as well as increased genomic complexity such as seen in the polyploid carp, comparative analysis of genes identified as causing change in adult form in model species can reveal mechanisms underlying variation of the skeleton and other traits in non-model organisms.

Fish phenocopies

Several laboratories have recently extended mutagenesis screens in zebrafish and medaka to explore genes affecting late development (e.g. ZF-MODELS, Andreeva et al., 2011; and others). Many of these screens focus on the formation of the adult skeleton and changes in pigmentation as these phenotypes are easily identified and thus allow for large numbers of genomes to be screened without intensive analysis. The majority of screens have used zebrafish, however screens in both zebrafish and medaka have been carried out in our lab (unpublished results). As the genes underlying the mutant phenotypes are currently being identified, the applicability of the findings of these screens to both human disease modelling as well as to fish phenotypic variation and disease needs to be verified. Recent cloning of several adult skeletogenic mutants in both models has identified conserved aspects of endocrine regulation of skeletal growth and pigment cell differentiation/patterning (McMenamin et al., 2013), genes involved in bone maturation (Asharani et al., 2012; Bowen et al., 2012), as well as novel signalling involved in fin identity, size and patterning (Moriyama et al., 2012; Perathoner et al., 2014). However, the vast majority of mutants affecting adult traits have yet to be described.

In support of our original findings, ongoing phenotypic analyses of mutants stemming from our screens show distinct phenocopies resembling teratologies in both humans and in fish. As these screens have analyzed a large number of genes (>10 000 genomes), several mutants with similar phenotypes have been identified suggesting mutations in multiple genes within a common pathway. Here, we describe mutants identified in current screens in our lab that show promise to serve as models of skeletal anomalies observed in farmed fish.

Insights into skeletogenesis and the causes of skeletal deformities

Skeletal malformations of famed fish are a continual challenge for the aquaculture industry. Skeletal malformations affect an animal’s overall performance, growth and cause concerns about animal welfare. Malformed fish also cause monetary losses due to product downgrading. There is evidence that the aetiology of skeletal malformations in farmed fish are different in advance marine species (Boglione et al., 2013a; Izquierdo et al., 2013; Loizides et al., 2013) than observed in salmonids (Fjelldal et al., 2013). In marine species, malformations typically relate to events early in development and malformations can be connected to high rates of larval mortality (Boglione et al., 2013b). In contrast, in farmed salmonids skeletal malformations often occur later in life (Fjelldal et al., 2012a,b). The aetiology of the common types of skeletal malformations in salmonids has been studied in detail and the environmental risk factors that trigger these malformations are known (Wargelius et al., 2005; Fjelldal et al., 2007, 2012b; Aunsmo et al., 2009; Witten et al., 2009). Still malformations occur and there is room for optimisation, especially for triploid salmonids that are increasingly used for farming (Madsen et al., 2000; Fjelldal and Hansen, 2010; Poirier Stewart et al., 2014). As the genetic and environmental causes of susceptibility are complex and integrative, the removal of one risk factor alone often does not solve the problem (Fjelldal et al., 2012a,b). Interestingly, several malformations that occur under farming conditions can also be observed in salmon under natural conditions (Sambraus et al., 2013). A deeper understanding of the development of skeletal anomalies and the genetic and environmental causes of their formation will greatly facilitate efforts to reduce the prevalence of these diseases in many species of farmed fish.

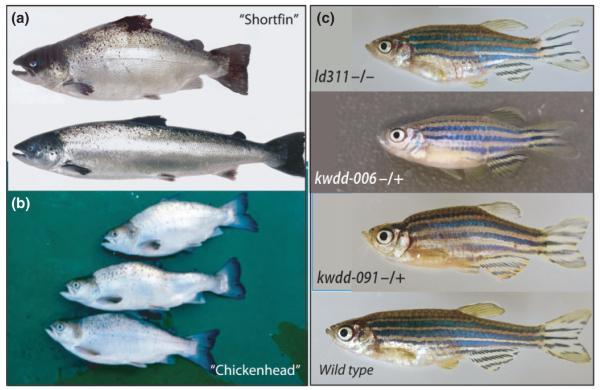

We performed mutagenesis screens in both the zebrafish and medaka for mutations affecting skeletal form of the adult. In these screens, we have identified classes of mutants with skeletal phenotypes affecting the skull, fins and the vertebral column of the adult fish. Some of these mutants closely resemble common skeletal variants seen in many farmed fish (Fig. 2). Importantly, similar to the variation observed in farms, many of these phenotypes are not fully penetrant and may depend on particular rearing conditions and/or genetic background. However, in each case presented below, clear Mendelian inheritance is observed. The mutants are discussed in relation to their use for comparative analysis between fishes. A full description of the screen and mutants will be presented at a later date.

Fig. 2.

Mutant phenocopies of common skeletal malformations in farmed salmon. (a, b) Axial shortening defects in farmed Atlantic salmon showing arched back and short body axis commonly referred to as ‘short tails’or ‘shorty’. Wild type salmon shown at bottom of a. (b) ‘Chicken head’ deformity of Atlantic salmon occurring in tandem with axial defects. (c) Zebrafish mutants identified in current mutagenesis screens affecting development of form of the adult skeleton with a shortened primary axis while retaining general patterning and morphology. These mutants are generally classified as ‘stumpy’, however each mutant phenotype is caused by mutation at an independent genetic locus (name, bottom left) and has unique characteristics. A complex phenotype with axial shortening and depressed posterior skull and arched ‘hump’ (kwdd-091) similar to ‘chicken head’ seen in Atlantic salmon (b). Wild type zebrafish shown on the bottom. Images in a) courtesy of Dr. P. E. Witten, after (Witten et al., 2005); (b), adapted from (Sullivan et al., 2007), used with permission

Vertebral malformations

Shortening of the vertebral column

One frequent mutant phenotype we observe in zebrafish is axial shortening while overall proportions of other components of the body are maintained; these are referred to as ‘stumpy’ mutants. Similar phenotypes are described in hatcheries as ‘short tail’ (Fig. 2) (Witten et al., 2009). Anterior-posterior compressed vertebral bodies, fused vertebral bodies and combinations of both phenotypes are commonly observed in farmed salmonids but also in advanced marine teleosts (Kranenbarg et al., 2005a,b; Witten et al., 2009). A connection between compression and fusion of vertebral bodies and the insufficient mineralisation of vertebral body has been observed in studies that follow the development of vertebral fusions (Witten et al., 2006, 2009). Different from tetrapods and basal osteichthyans, in all teleosts, the mineralisation of the notochord sheath establishes the anlage of the vertebral body (Bensimon-Brito et al., 2012a,b). In advanced marine teleost species, alterations in axial development and vertebral fusion are thus often related to notochord defects (Willems et al., 2012; Loizides et al., 2013). There is increasing evidence that in humans, the remains of the notochord (nucleus pulposus) are also responsible for maintaining healthy intervertebral joints (Shapiro and Risbud, 2010; Risbud and Shapiro, 2011). This is apparently also the case for teleost fishes since alterations of the notochord that is located in the intervertebal space cause vertebral fusion (Witten et al., 2005; Loizides et al., 2013). Medaka and zebrafish have been important models in which to study the relationship between early vertebral body fusion and notochord mineralisation (Spoorendonk et al., 2008; Bensimon-Brito et al., 2012a,b; Willems et al., 2012). As many of our mutants having vertebral phenotypes do not have an obvious larval phenotype, our data points to mechanisms active during later phases of development that regulate vertebral patterning. This observation is consistent with the finding that many vertebral deformities in Atlantic salmon are due to changes that manifest in late development as well (e.g. Witten et al., 2005; Fjelldal et al., 2012a,b).

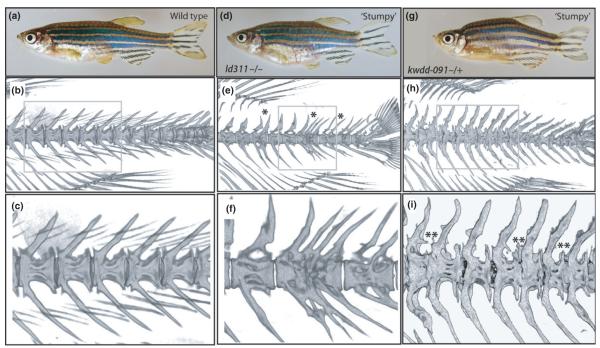

In zebrafish mutants, axial shortening phenotypes can be due to both recessive and dominant mutations. The dominant mutants often show dose sensitivity as homozygotes exhibit more severe phenotypes than siblings carrying one altered allele. Similar to descriptions of deformities in Atlantic salmon (Witten et al., 2005, 2009; Sullivan et al., 2007), initial analysis of the skeleton in these zebrafish mutants suggests that mutants having similar phenotypes can have different aetiologies. For example, the stumpy mutant, ld311, is a recessive mutation resulting in axial shortening (Fig. 3). Analysis of the spine of an adult ld311 mutant by microcomputed tomography (microCT) shows several areas of vertebral fusion while maintaining overall vertebral morphology and spinal linearity (Fig. 3e). Like in salmon, fusion of vertebrae can be identified by observation of multiple haemal and neural arches emanating from a single vertebral body (Fig. 3f) (Witten et al., 2006, 2009). No phenotype is detected in larval stages in this mutant. In other zebrafish mutants exhibiting ‘stumpy’ phenotypes, we have observed skull malformations leading to depression of the posterior cranium, frontonasal shortening, in addition to vertebral body compression (Figs 2c, 3g). In contrast to ld311, analysis of the vertebrae from animals heterozygous for the kwdd-091mutation suggests that the shortened spine is caused by compression (reduction of individual vertebral width), as the number of vertebrae is similar to wild type siblings (Fig. 3b, h). Anterior to the side of vertebral fusion, neural arches in these animals display extended bone apolamellae, while the fusion side displays osteopetrotic bone overgrowth (Fig. 3i). Interestingly this phenotype is broadly similar to vertebral fusion that occurs as a consequence of metaplastic chondrogenesis (Witten et al., 2006), however, it will require further analysis of the anatomical basis of the fusion.

Fig. 3.

Multiple aetiologies of common phenotypes: vertebral shortening. (a) Wild type adult zebrafish (ld311 sibling). (b, c) MicroCT analysis showing normal spinal patterning. (d) Homozygous ‘stumpy’ mutant ld311, showing a spinal fusion centre in the adult. (e) MicroCT rendering of ld311 showing vertebral compression and fusion but no bending of the spine. (f) Fusion of multiple vertebrae suggests the origin of a fusion centre (Witten et al., 2006) as multiple neural and hemal spines are integrated within modified vertebrae. (g) Another ‘stumpy’ mutant kwdd-091, caused by a dominant mutation. (h) MicroCT rendering of the spine of an adult kwdd-091 mutant exhibits compression and fusion of vertebral bodies combined with osteopetrosis. (i) In contrast to ld311, the number and pattern of vertebrae are comparable to unaffected siblings (b), however individual vertebrae are compressed and fused, indicating alterations of the vertebral body growth zone and the intervertebral space (asterisks). Grey box in b, e, and h demarcates area of magnification shown in c, f and i, respectively. * sites of fusion; ** sites of compression and fusion of vertebrae. MicroCT performed at 6 μm resolution

The co-inheritance of axial vertebral body compression and other skeletal deformities observed in the kwdd-091 mutant is also observed in the Atlantic salmon ‘chicken head’ phenotype (an obvious step behind the head) described by Sullivan et al. (2007). The occurrence of these two phenotypes as a result of a single mutation in the zebrafish provides evidence that the cause of the head and spine deformities is due to a common genetic defect. The identification of the altered gene in this mutant could provide a mechanistic tool towards understanding the cause of coinciding head and spinal deformities in farmed fish.

Scoliosis, kyphosis and lordosis

In addition to ‘stumpy’ or ‘short tail’ phenotypes, we observe mutants with axial curvature. Several different classes of axial deformity mutants were identified based on the position and the direction of the curvature: lordosis, kyphosis, and scoliosis. The position of the affected vertebrae is consistent within particular mutants and thus the type of curvature appears to be specific for the particular mutant class.

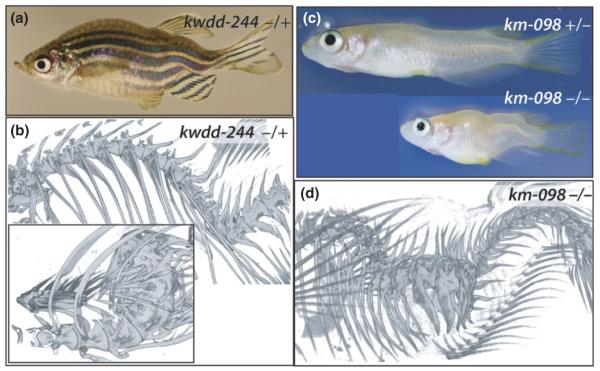

The zebrafish mutant kwdd-244 exhibits a dominant effect on vertebral development resulting in multiple sites of axial deformity (Fig. 4a). Analysis of the spine from adult heterozygote kwdd-244 fish indicates presence of anterior kyphosis while retaining normal patterning and general morphology of the vertebrae (Fig. 4b). In the posterior region however, there is a lateral turn of the spine that shows changes in vertebral shape coinciding with the scoliotic curvature (Fig. 4b inset). The kwdd-244 mutant does not have an apparent larval phenotype, rather the phenotype manifests during juvenile development. We have additionally identified mutants in the medaka that exhibit similar complex spinal curvature defects. The km-098 mutant is dominant with dose dependent effects on axial curvature (Fig. 4c). Analysis of the adult skeleton shows complex deformation of the spine with kyphosis, scoliosis, and lordosis in the adult. Heterozygotes are mildly affected while homozygotes have extreme deformities (Fig. 4d). It is unknown if in these mutants vertebral development is directly affected or if the curvature of the spine is caused indirectly through neuro-muscular defects.

Fig. 4.

Identification of mutants with vertebral column curvatures. (a) Zebrafish mutant kwdd-244 causing strong vertebral curvature of kyphosis, lordosis, and scoliosis. (b) Analysis of the vertebral column of kwdd-244 shows strong curvature of the spine in the anterior region however having relatively normal patterning and form of the vertebral bodies. In contrast, at sites of strong deformation the centra of the vertebrae are trapezoidal associated with the onset of curvature (inset, caudal view). (c) Medaka mutant km-098 exhibits a mild axial curvature in heterozygotes, however this mutation shows dose sensitivity as homozygotes show extreme curvature similar to that seen in the kwdd-244 zebrafish mutant (a). (d) Lateral view of homozygous km-098 showing lordosis and scoliosis of the mid trunk

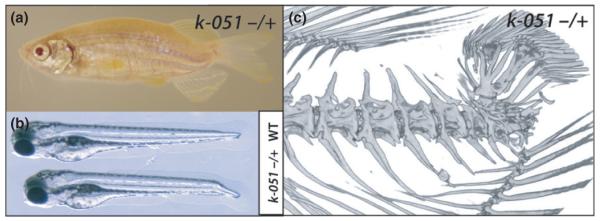

A third class of mutants exhibits axial deformities that primarily affect the caudal peduncle, as seen in the k-051 mutant (Fig. 5a). The k-051 mutant phenotype arises in part due to changes in larval development as defects in the posterior portion of the notochord (Fig. 5b). Analysis of the adult skeleton shows vertebral body compression and extreme dorsal curving of the caudal vertebrae with dorsally located hypural arches. (Fig. 5c). Sea bream larvae (Sparus aurata) exhibit a high frequency of deformities that manifest into adult skeletal phenotypes comparable to those shown here (Koumoundouros et al., 1997a).

Fig. 5.

Mutants having deformities of the caudal fin and peduncle. (a) Mutant k-051 shows dominant shortening of the caudal region of the spine and deformation of the caudal fin. (b) This mutant phenotype is due to a developmental defect affecting early notochord formation in the embryo. Shown are wild type (top) and k-051 mutant (bottom) larvae at 3 days post fertilization. (c) Analysis of adult skeleton by microCT shows little effect of the mutation on anterior vertebrae, rather compaction of the caudal vertebrae, extreme dorsal displacement of hypurals with retention of the caudal fin skeleton

Craniofacial deformities

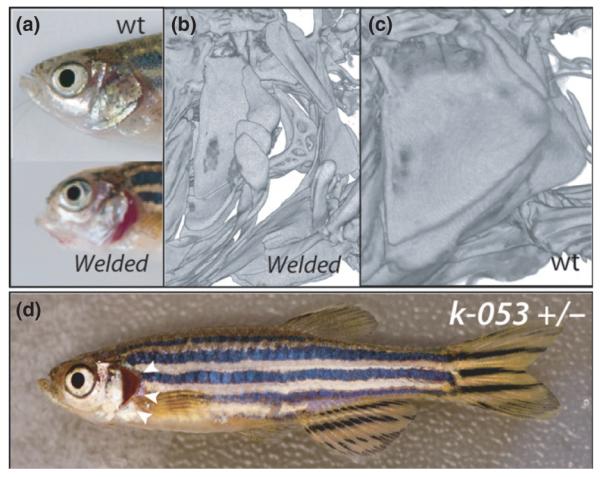

Craniofacial phenotypes observed in our screen and in nature are varied and numerous. However, only a few phenotypes appear to be compatible with viability and most variant morphologies fall within a few general classes. Common variations include hyper- or hypotrophy of the jaw (‘gaping’, ‘screamer disease’), shortening of the opercular apparatus as well as pre-oribital shortening (‘pugnose’). The ‘pugnose’ craniofacial phenotype is a reoccurring class of mutants that we see in our screens (Fig. 6a) that is also prevalent in natural variation among fishes as well as arising in aquaculture (Boglione et al., 2013b; Cobcroft et al., 2013). These mutant phenotypes in the zebrafish are caused variously by both dominant and recessive alleles inherited with expected Mendelian frequencies. For example, the welded zebrafish mutant exhibits shortening of the frontonasal aspect of the skull (Fig. 6a). The altered gene in the mutant affects bone differentiation and is associated with axial shortening and fin shape defects as well (Fig. 6) (Asharani et al., 2012; Bowen et al., 2012). Mutants exhibiting pre-orbital shortening have been recovered in both medaka and zebrafish screens, however they are more prevalent in the latter. Associated with many craniofacial mutants is a deformity that results in a terminal infolding of the bones of the opercular complex (Fig. 6b, c). The opercular complex is composed of dermal bones covering the gills that appear early in development compared to other bones. Koumoundouros et al. (1997b) report that over 80% of reared Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) suffer from the unilateral infolding of operculae. Defects in gill covering adversely affect respiration, cause oxygen stress and can lead to bacterial infections of the gill lamellae. These skeletal defects can thus have a significant effect on rearing efficiency (Boglione et al., 2013b). Wild type zebrafish stocks reared in the laboratory setting exhibit rare operculum deformities that can be identified by the visible exposure of the gills in adults. We have not observed a similar variance in medaka. During our screens, we identified a large number of lines containing opercular defects with variable penetrance (Fig. 6d), although these were often too variable to maintain. However, in recent screens several mutants could be identified having a clear Mendelian inheritance. Some of these mutants, like welded, have broad effects on the development and differentiation of the skeleton, suggesting the opercular complex is sensitive to changes in growth as well as change in osteogenic ability (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Craniofacial phenotypes. (a) Zebrafish welded mutant as an example of preorbital shortening of the skull observed in many mutants. (b) Analysis of the skeleton of welded by microCT shows defects in development of the elements of the opercular apparatus leading to the exposure of the gills and is found consistently in mutants. (c) MicroCT of welded siblings. (d) Dominant opercular folding phenotype in line k-053 (arrowheads) without other shared skeletal phenotypes; this is seen at moderate frequency in screens and but was not followed up to re-identify

Fin deformities

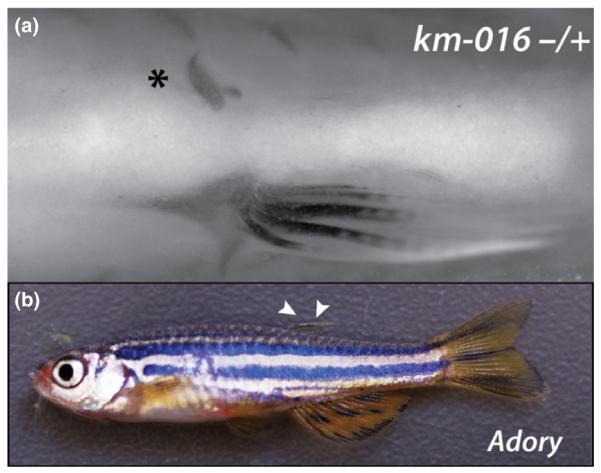

The proximal elements of the fin skeleton belong to the endoskeleton and are made from cartilage and bone. The distal fin rays (lepidotricha) are part of the post-cranial dermal skeleton and are formed from intramembraneous ossification (Witten and Huysseune, 2007). Defects of the fin skeleton can arise from many causes, both genetic and environmental. Normal development of the caudal fin endoskeleton requires the fusion of several vertebral bodies. Paradoxically, in other parts of the spine similar fusion causes spinal deformities (Bensimon-Brito et al., 2012a). Vertebral rudiments, vestiges, and a high degree of variability including fusion of pre-caudal vertebral bodies are regularly observed during caudal fin development in wild-type teleosts (Witten and Huysseune, 2009; Witten et al., 2009). Accordingly, caudal fin deficiencies are common in farmed fish and can be quite varied. The incidence of caudal fin phenotypes in farmed marine teleosts is reported to be quite high [60–100%; (Koumoundouros, 2010)]. We have identified various mutants with deficiencies that are similar as common deformations of the caudal fin and pre-caudal vertebrae (e.g. Fig. 5). Additionally, mutants have been recovered that affect development of the paired fins. Some are quite extreme leading to the reduction or loss of lepidotrichia on all fins, leading to a ‘finless’ phenotype (e.g. Harris et al., 2008). In addition, more subtle phenotypes have been recovered such as variation in pelvic fins having unilateral and bilateral deficiencies (Fig. 7a). Reduction in pelvic fins have been seen as a common variant in many domesticated species (e.g. common carp, Kirpicnikov, 1987); European sea bass (Boglione et al., 2013b), and wild populations of sticklebacks (Bell et al., 2007).

Fig. 7.

Mutants phenocopying fin variation seen in wild and farmed fish species. (a) Skeletal preparation of medaka mutant km-016 showing an example of asymmetric pelvic fin loss (*); alizarin red staining. (b) Dominant mutation affecting dorsal fin growth (arrowheads) in the zebrafish adory mutant. The external appearance resembles the ‘saddleback’ syndrome seen in several farmed marine fish species

The reduction or absence of dorsal fins is another fin deformity observed in many wild caught and farmed fish species (e.g. Dentex dentex, and the common carp, C. carpio) referred to as ‘saddleback syndrome’ (Koumoundouros et al., 2001). We find that saddleback phenotypes can arise due to single mutations in zebrafish and thus may have a simple developmental cause. For example, the mutant adory is dominant and shows dose-dependent loss of the dorsal fin (Fig. 7b); the phenotype is quite specific and the mutation affects only the presence of the dorsal fin mirroring the phenotype described as ‘saddleback’ in many different species (Sfakianakis et al., 2003; Setiadi et al., 2006; Korkut et al., 2009; Diggles, 2013). Interestingly, a dominantly inherited disorder resembling ‘saddleback’ has been previously described in the cichlid, Oreochromis aureus, showing dose dependency and resulting in increased lethality (Tave et al., 1983). Thus it is likely that there is a strong genetic component underlying susceptibility for this fin abnormality. Due to the experimental ease of zebrafish in identification of the causative mutation, the genetic basis underlying this phenotype can be ascertained.

The identification of mutant models of these common abnormalities observed in other fish species allows for dissection of the hereditary basis underlying the appearance of these traits and may provide clues to the environmental and genetic controls of skeletal variation in aquaculture. The fact that zebrafish and medaka represent the two main branches of teleost fishes make them ideal models.

Expansion of analysis

In a recent review, Boglione et al. (2013a) argue for the need of better classification of skeletal abnormalities in fish in order to discern causes of skeletal dysplasias. For this very reason, such terminology has been proposed for spinal deformities that are commonly observed in Atlantic salmon (Witten et al., 2009) but are indeed lacking for species from other fish families and for other parts of the skeleton. This lack of specificity leads to grouping of phenotypes that may arise from quite different mechanisms. As shown in our data, grouping of gross morphological effects rather than specific phenotypes can be helpful in identifying diverse regulators of vertebral development (Fig. 2). However, detailed analysis of the effects of mutation is required to better identify the cellular and tissue level deficiencies underlying the pathologies. Only then can informed strategies to alleviate potential causes be made.

Our initial analysis of mutants affecting adult form in zebrafish and medaka used broad phenotypic selection criteria. The use of more detailed screening assays designed to identify specific aspects of skeletal differentiation or pattern will permit for more subtle, but important phenotypes to be identified. For example, genes that affect bone density or fragility may not have been efficiently identified in our screens because the effect of mutation may not significantly affect gross morphology in the stages analyzed. Use of transgenic markers of particular cell types (e.g. osteoblasts) or assays such as alkaline phosphatase activity may reveal a larger class of mutants that would be important for an in-depth analysis of skeletal development in these models. Nevertheless, the identification of broad phenotypic classes is important to characterize skeletogenesis as well as to address causes of skeletal anomalies in aquaculture. As our screen is one of several that are currently ongoing, there is an increasing potential for discovery and creation of tools to address genetic and developmental basis of patho-physiological states in fish of diverse classes.

In our analyses we focus on mutations that affect the adult skeleton. However, to fully capitalise on the utility of mutagenesis approaches, it will be important to develop informative phenotypic assays to identify mutants affecting different aspects of development, physiology and behavior. Promising areas of research that have successfully used laboratory fish models include (I) analysis of metabolism and the effect of nutrition in growth, fecundity, and health of fish; (II) the genetic regulation of reproduction, sexual differentiation, and fecundity (e.g.(Kondo et al., 2009a; Saito and Tanaka, 2009; Kikuchi and Hamaguchi 2013; Liew and Orban 2013)); (III) regulation of behavior including schooling (Engeszer et al., 2008; Wark et al., 2011; Miller and Gerlai 2012; Greenwood et al., 2013; Kowalko et al., 2013; Liew and Orban 2013), aggression (Norton et al., 2011; Ariyomo et al., 2013) and reproduction; (IV) teratology and environmental toxicology (e.g. (Nakayama et al., 2005; Khalil et al., 2013)); and lastly (V) immunity (Sullivan and Kim 2008; Rauta et al., 2012; Renshaw and Trede 2012). Such broad genetic analysis in laboratory models can then provide specific research models for diseases affecting both fish and humans. For example, forward genetic analyses in the zebrafish has uncovered essential mechanisms of tuberculosis infection and led to the identification of specific molecular regulators of resistance in fish (Swaim et al., 2006; Carvalho et al., 2011; Parikka et al., 2012; Ramakrishnan, 2013). Extension of these approaches can be applied to other infectious diseases (Sieger et al., 2009; Patterson et al., 2012) as well as how susceptibility is associated with the occurrence of other defects (e.g. opercular development or wound repair).

Convergence or parallelism?

Comparative analysis has shown that similar genetic mechanisms are often used in the formation and variation of shared derived phenotypes (Colosimo et al., 2005; Shapiro et al., 2006; Rohner et al., 2009). Such parallel mechanisms underlying the regulation of form in unrelated species support the use of comparative analysis to delimit the causes of variation. However, as shown in our analysis of ‘stumpy’ mutants (Fig. 3), similar morphologies may have diverse causes within one species – the genetic causes of these skeletal dysplasias would be expected to be similarly diverse. Thus, knowledge of a particular cause of a phenotype does not necessarily determine that this will be the only means by which the phenotype will occur. True convergence instead of parallelism may constrain the predictive ability of model species in comparative analysis. However, because of developmental and historical constraints in species, the number of causes of a particular phenotype will be limited; given a suitable depth of analysis for phenotypes, many of the causes can be defined as long as the trait is a shared characteristic among the compared groups (e.g. Fig. 3). Thus, cases of phenotypic convergence may still retain mechanistic details that can be predictive and informative of changes within other species.

Perspectives on a phenocopy approach and the potential for experimental models to understand fish

Many researchers have not embraced the use of zebrafish and medaka as tools to address questions concerning other teleosts. Boglione et al. (2013b) argue that in context of vertebral malformations that even kinship to a particular family does not justify transfer of information between species as farming conditions can be quite different and may lead to different aetiologies. However, the zebrafish and medaka have been successfully used as a model for human disease as well as a means to define key aspects of vertebrate evolution. As such, arguments disregarding the utility and importance of similar approaches toward understanding fish of another family or order are not supported and limit the potential of an integrated, comparative approach to understand the causes of morphological variation and disease.

The mutant phenotypes identified in mutagenesis screens provide a foundation in which to investigate essential signalling functions and developmental mechanisms underlying skeletal pathologies observed in other fish as well as to understand the effects of selective breeding or transgenic approaches on growth, physiology and health. The combination of screens in both zebrafish and medaka, allows for experimental versatility as well as the ability to assess potential bias between different experimental models for particular phenotypes given their phylogenetic history and similarity to different fishes under study. Expansion of current phenotypic analyses will broaden the utility of these experimental models and provide important tools to address the causes of variation among fishes and within fish.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology for use of Micro computed tomography and Orthopaedic Surgery Foundation (COSF) at Boston Children’s Hospital for generous support. This work was funded through grant support NIDCR 1 R56 DE022790-01A1 to MPH. PEW thanks his co-organiser of the IAFSB 2013 congress Leonor Cancela, all members of the local organising committee and the Skretting Aquaculture Research Centre (Norway) for supporting the publication of this volume.

References

- Albertson RC, Streelman JT, Kocher TD, Yelick PC. Integration and evolution of the cichlid mandible: the molecular basis of alternate feeding strategies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16287–16292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506649102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf FW, Danzmann RG. Secondary tetrasomic segregation of MDH-B and preferential pairing of homeologues in rainbow trout. Genetics. 1997;145:1083–1092. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf FW, Thorgaard GH. Tetraploidy and the evolution of salmonid fishes. In: Turner BJ, editor. Evolutionary genetics of fishes. Plenum Press; New York: 1984. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva V, Connolly MH, Stewart-Swift C, Fraher D, Burt J, Cardarelli J, Yelick PC. Identification of adult mineralized tissue zebrafish mutants. Genesis. 2011;49:360–366. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansai S, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Ariga H, Uemura N, Takahashi R, Kinoshita M. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in medaka using custom-designed transcription activator-like effector nucleases. Genetics. 2013;193:739–749. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.147645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansai S, Inohaya K, Yoshiura Y, Schartl M, Uemura N, Takahashi R, Kinoshita M. Design, evaluation, and screening methods for efficient targeted mutagenesis with transcription activator-like effector nucleases in medaka. Dev. Growth Differ. 2014;56:98–107. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyomo TO, Carter M, Watt PJ. Heritability of boldness and aggressiveness in the zebrafish. Behav. Genet. 2013;43:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s10519-013-9585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asharani PV, Keupp K, Semler O, Wang W, Li Y, Thiele H, Yigit G, Pohl E, Becker J, Frommolt P, Sonntag C, Altmuller J, Zimmermann K, Greenspan DS, Akarsu NA, Netzer C, Schönau E, Wirth R, Hammerschmidt M, Nurnberg P, Wollnik B, Carney TJ. Attenuated BMP1 function compromises osteogenesis, leading to bone fragility in humans and zebrafish. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aunsmo A, Ovretveit S, Breck O, Valle PS, Larssen RB, Sandberg M. Modelling sources of variation and risk factors for spinal deformity in farmed Atlantic salmon using hierarchical- and cross-classified multilevel models. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009;90:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Oliveri A, Levin ED. Zebrafish model systems for developmental neurobehavioral toxicology. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo Today. 2013;99:14–23. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell VM, Wang Y, Campbell JM, Poshusta TL, Starker CG, Krug RG, Tan W, Penheiter SG, Ma AC, Leung AY, Fahrenkrug SC, Carlson DF, Voytas DF, Clark KJ, Essner JJ, Ekker SC. In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system. Nature. 2012;491:114–118. doi: 10.1038/nature11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Khalef V, Travis MP. Directional asymmetry of pelvic vestiges in threespine stickleback. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2007;308:189–199. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon-Brito A, Cancela ML, Huysseune A, Witten PE. Vestiges, rudiments and fusion events: the zebrafish caudal fin endoskeleton in an evo-devo perspective. Evol. Dev. 2012a;14:116–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon-Brito A, Cardeira J, Cancela ML, Huysseune A, Witten PE. Distinct patterns of notochord mineralization in zebrafish coincide with the localization of Osteocalcin isoform 1 during early vertebral centra formation. BMC Dev. Biol. 2012b;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge MCM, Thilsted SH, Phillips MJ, Metian M, Troell M, Hall SJ. Meeting the food and nutrition needs of the poor: the role of fish and the opportunities and challenges emerging from the rise of aquaculture. J. Fish Biol. 2013;83:1067–1084. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boglione C, Gavaia P, Koumoundouros G, Gisbert E, Moren M, Fontagne S, Witten PE. Skeletal anomalies in reared European fish larvae and juveniles. Part 1: normal and anomalous skeletogenic processes. Rev. Aquacult. 2013a;5:S99–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Boglione C, Gisbert E, Gavaia P, Witten PE, Moren M, Fontagne S, Koumoundouros G. Skeletal anomalies in reared European fish larvae and juveniles. Part 2: main typologies; occurrences and causative factors. Rev. Aquacult. 2013b;5:S121–S167. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen ME, Henke K, Siegfried KR, Warman ML, Harris MP. Efficient mapping and cloning of mutations in zebrafish by low-coverage whole-genome sequencing. Genetics. 2012;190:1017–1024. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade L, Reyon D, Hwang WY, Tsai SQ, Patel S, Khayter C, Joung JK, Sander JD, Peterson RT, Yeh JR. Highly efficient generation of heritable zebrafish gene mutations using homo- and heterodimeric TALENs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8001–8010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho R, de Sonneville J, Stockhammer OW, Savage ND, Veneman WJ, Ottenhoff TH, Dirks RP, Meijer AH, Spaink HP. A high-throughput screen for tuberculosis progression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang N, Sun C, Gao L, Zhu D, Xu X, Zhu X, Xiong JW, Xi JJ. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res. 2013;23:465–472. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KJ, Boczek NJ, Ekker SC. Stressing zebrafish for behavioral genetics. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;22:49–62. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobcroft JM, Battaglene SC. Skeletal malformations in Australian marine finfish hatcheries. Aquaculture. 2013;396:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Colosimo PF, Hosemann KE, Balabhadra S, Villarreal G, Dickson M, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Schluter D, Kingsley DM. Widespread parallel evolution in sticklebacks by repeated fixation of Ectodysplasin alleles. Science. 2005;307:1928–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1107239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:836–846. doi: 10.1038/nrg1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WJ, Wirgau RM, Sweet EM, Albertson RC. Deficiency of zebrafish fgf20a results in aberrant skull remodeling that mimics both human cranial disease and evolutionarily important fish skull morphologies. Evol. Dev. 2013;15:426–441. doi: 10.1111/ede.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahme T, Katus HA, Rottbauer W. Fishing for the genetic basis of cardiovascular disease. Dis. Model Mech. 2009;2:18–22. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggles BK. Saddleback deformities in yellowfin bream; Acanthopagrus australis (Gunther), from South East Queensland. J. Fish Dis. 2013;36:521–527. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Malicki J, Stemple DL, Stainier DY, Zwartkruis F, Abdelilah S, Rangini Z, Belak J, Boggs C. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart JK, He X, Swartz ME, Yan YL, Song H, Boling TC, Kunerth AK, Walker MB, Kimmel CB, Post-lethwait JH. MicroRNA Mirn140 modulates Pdgf signaling during palatogenesis. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:290–298. doi: 10.1038/ng.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeszer RE, Wang G, Ryan MJ, Parichy DM. Sexspecific perceptual spaces for a vertebrate basal social aggregative behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:929–933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708778105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . State of world fisheries and aquaculture. FAO; Rome: 2012. p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaz AW, Leon-Kloosterziel KM, Schulte-Merker S. Exploring the effect of exercise on the transcriptome of zebra-fish larvae (Danio rerio) J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014;30:753–761. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal PG, Hansen T. Vertebral deformities in triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) underyearling smolts. Aquaculture. 2010;309:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal PG, Hansen TJ, Berg AE. A radiological study on the development of vertebral deformities in cultured Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Aquaculture. 2007;273:721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal PG, Hansen T, Breck O, Ørnsrud R, Lock EJ, Waagbø R, Wargelius A, Witten PE. Vertebral deformities in farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) – etiology and pathology. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012a;28:433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal PG, Hansen T, Albrektsen S. Inadequate phosphorus nutrition in juvenile Atlantic salmon has a negative effect on long-term bone health. Aquaculture. 2012b;334:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Fjelldal PG, Totland GK, Hansen T, Kryvi H, Wang X, Sondergaard JL, Grotmol S. Regional changes in vertebra morphology during ontogeny reflect the life history of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) J. Anat. 2013;222:615–624. doi: 10.1111/joa.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furutani-Seiki M, Sasado T, Morinaga C, Suwa H, Niwa K, Yoda H, Deguchi T, Hirose Y, Yasuoka A, Henrich T, Watanabe T, Iwanami N, Kitagawa D, Saito K, Asaka S, Osakada M, Kunimatsu S, Momoi A, Elmasri H, Winkler C, Ramialison M, Loosli F, Quiring R, Carl M, Grabher C, Winkler S, Del Bene F, Shinomiya A, Kota Y, Yamanaka T, Okamoto Y, Takahashi K, Todo T, Abe K, Takahama Y, Tanaka M, Mitani H, Katada T, Nishina H, Nakajima N, Wittbrodt J, Kondoh H. A systematic genome-wide screen for mutations affecting organogenesis in Medaka, Oryzias latipes. Mech. Dev. 2004;121:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlai R. Using zebrafish to unravel the genetics of complex brain disorders. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2012;12:3–24. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs EM, Horstick EJ, Dowling JJ. Swimming into prominence: the zebrafish as a valuable tool for studying human myopathies and muscular dystrophies. FEBS J. 2013;280:4187–4197. doi: 10.1111/febs.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PH, Rosen DE, Weitzmans H, Myersg S. Phyletic studies of teleostian fishes; with a provisional classification of living forms. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1966;131:339–456. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood AK, Wark AR, Yoshida K, Peichel CL. Genetic and neural modularity underlie the evolution of schooling behavior in threespine sticklebacks. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1884–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Kane DA, Odenthal J, van Eeden FJM, Jiang Y-J, Heisenburg CP, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996a;12:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P, Odenthal J, Mullins MC, Lin S, Farrell MJ, Vogelsang E, Haas F, Brand M, van Eeden FJM, Furutani-Seiki M, et al. Mutations affecting pigmentation and shape of the adult zebrafish. Dev. Genes. Evol. 1996b;206:260–276. doi: 10.1007/s004270050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MP. Comparative genetics of postembryonic development as a means to understand evolutionary change. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012;28:306–315. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MP, Rohner N, Schwarz H, Perathoner S, Konstantinidis P, Nusslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish eda and edar mutants reveal conserved and ancestral roles of ectodysplasin signaling in vertebrates. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruscha A, Krawitz P, Rechenberg A, Heinrich V, Hecht J, Haass C, Schmid B. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing with low off-target effects in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:4982–4987. doi: 10.1242/dev.099085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, Maeder ML, Tsai SQ, Sander JD, Peterson RT, Yeh JR, Joung JK. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo MS, Scolamacchia M, Betancor M, Roo J, Cabal-lero MJ, Terova G, Witten PE. Effects of dietary DHA and á-tocopherol on bone development; early mineralisation and oxidative stress in Sparus aurata (Linnaeus, 1758) larvae. Br. J. Nutr. 2013;109:1796–1805. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L, Zon LI. Zebrafish as a model for normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011;4:433–438. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan FS, Chakkalakal SA, Shore EM. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: mechanisms and models of skeletal metamorphosis. Dis. Models Mech. 2012;5:756–762. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil F, Kang IJ, Undap S, Tasmin R, Qiu X, Shimasaki Y, Oshima Y. Alterations in social behavior of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) in response to sublethal chlorpyrifos exposure. Chemosphere. 2013;92:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Hamaguchi S. Novel sex-determining genes in fish and sex chromosome evolution. Dev. Dyn. 2013;242:339–353. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirpicnikov VS. VEB Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag DDR. Berlin: 1987. Genetische Gundlagen der Fishzuechtung. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Nanda I, Schmid M, Schartl M. Sex determination and sex chromosome evolution: insights from medaka. Sex Dev. 2009a;3:88–98. doi: 10.1159/000223074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Iwashita M, Yamaguchi M. How animals get their skin patterns: fish pigment pattern as a live Turing wave. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2009b;53:851–856. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072502sk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkut AY, Kamaci HO, Coban D, Suzer C. The first data on the saddleback syndrome in cultured gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) by MIP-MPR Method. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2009;8:2360–2362. [Google Scholar]

- Koumoundouros G. Morpho-anatomical abnormalities in Mediterranean marine aquaculture. In: Recent advances in aquaculture research. In: Koumoundouros G, editor. Transworld Research Network. Kerala, India: 2010. pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Koumoundouros G, Gagliardi F, Divanach P, Boglione C, Cataudella S, Kentouri M. Normal and abnormal osteological development of caudal fin in Sparus aurata L fry. Aquaculture. 1997a;149:215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Koumoundouros G, Oran G, Divanach P, Stefanakis S, Kentouri M. The opercular complex deformity in intensive gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) larviculture. Moment of apparition and description. Aquaculture. 1997b;156:165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Koumoundouros G, Divanach P, Kentouri M. The effect of rearing conditions on development of saddleback syndrome and caudal fin deformities in Dentex dentex (L.) Aquaculture. 2001;200:285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalko JE, Rohner N, Rompani SB, Peterson BK, Linden TA, Yoshizawa M, Kay EH, Weber J, Hoekstra HE, Jeffery WR, et al. Loss of schooling behavior in cavefish through sight-dependent and sight-independent mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1874–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenbarg S, Waarsing JH, Muller M, Weinans H, van Leeuwen JL. Lordotic vertebra in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) are adapted to increased loads. J. Biomech. 2005a;38:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenbarg S, van Cleynenbreugel T, Schipper H, van Leeuwen J. Adaptive bone formation in acellular vertebrae of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.) J. Exp. Biol. 2005b;208:3494–3502. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamason RL, Mohideen MA, Mest JR, Wong AC, Norton HL, Aros MC, Jurynec MJ, Mao X, Humphreville VR, Humbert JE, et al. SLC24A5.; a putative cation exchanger.; affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science. 2005;310:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1116238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C, Adatto I, Best J, James A, Maloney K. Generation time of zebrafish (Danio rerio) and medakas (Oryzias latipes) housed in the same aquaculture facility. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2012;41:158–165. doi: 10.1038/laban0612-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Chang CY, Hu NP, Wang YCJ, Lai CC, Herrup K, Lee WH, Bradley A. Mice deficient for RB are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and hematopoiesis. Nature. 1992;359:288–294. doi: 10.1038/359288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew WC, Orban L. Zebrafish sex: a complicated affair. Brief Funct. Genomics. 2013;13:172–187. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt041. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Leach SD. Zebrafish models for cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:71–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizides M, Georgiou AN, Somarakis S, Witten PE, Koumoundouros G. A new type of lordosis and vertebral body compression in Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata Linnaeus; 1758): aetiology, anatomy and consequences for survival. J. Fish Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jfd.12189. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12189; early view online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loosli F, Koster RW, Carl M, Kuhnlein R, Henrich T, Mucke M, Krone A, Wittbrodt J. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryonic development in medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) Mech. Dev. 2000;97:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L, Arnberg J, Dalsgaard I. Spinal deformities in triploid all-female rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish. Pathol. 2000;20:206–208. [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin SK, Minchin JE, Gordon TN, Rawls JF, Parichy DM. Dwarfism and increased adiposity in the gh1 mutant zebrafish vizzini. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1476–1487. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Gerlai R. From schooling to shoaling: patterns of collective motion in zebrafish (Danio rerio) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama Y, Kawanishi T, Nakamura R, Tsukahara T, Sumiyama K, Suster ML, Kawakami K, Toyoda A, Fujiyama A, Yasuoka Y, et al. The medaka zic1/zic4 mutant provides molecular insights into teleost caudal fin evolution. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan G, Jacks T. The retinoblastoma gene family: cousins with overlapping interests. Trends Genet. 1998;14:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Oshima Y, Hiramatsu K, Shimasaki Y, Honjo T. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyls on the schooling behavior of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005;24:2588–2593. doi: 10.1897/04-518r2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton W, Bally-Cuif L. Adult zebrafish as a model organism for behavioural genetics. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton WH, Stumpenhorst K, Faus-Kessler T, Folchert A, Rohner N, Harris MP, Callebert J, Bally-Cuif L. Modulation of Fgfr1a signaling in zebrafish reveals a genetic basis for the aggression-boldness syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:13796–13807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2892-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikka M, Hammaren MM, Harjula SK, Halfpenny NJ, Oksanen KE, Lahtinen MJ, Pajula ET, Iivanainen A, Pesu M, Ramet M. Mycobacterium marinum causes a latent infection that can be reactivated by gamma irradiation in adult zebrafish. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002944. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson H, Saralahti A, Parikka M, Dramsi S, Trieu-Cuot P, Poyart C, Rounioja S, Ramet M. Adult zebrafish model of bacterial meningitis in Streptococcus agalactiae infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012;38:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Zon LI. The art and design of genetic screens: zebrafish. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:956–966. doi: 10.1038/35103567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perathoner S, Daane J, Henrion U, Seebolm G, Higdon CW, Johnson SL, Nuesslein-Volhard C, Harris MP. Bio-electric signaling regulates size in zebrafish fins. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier Stewart N, Deschamps MH, Witten PE, Le Luyer J, Proulx E, Huysseune A, Bureau DP, Vandenberg GW. X-ray-based morphometrics: an approach to diagnose vertebral abnormalities in juvenile triploid all-female rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed a low mineral diet. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014;30:796–803. [Google Scholar]

- Porazinski SR, Wang H, Furutani-Seiki M. Essential techniques for introducing medaka to a zebrafish laboratory–towards the combined use of medaka and zebrafish for further genetic dissection of the function of the vertebrate genome. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;770:211–241. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-210-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley IK, Manuel JL, Roberts RA, Nuckels RJ, Herrington ER, MacDonald EL, Parichy DM. Evolutionary diversification of pigment pattern in Danio fishes: differential fms dependence and stripe loss in D. albolineatus. Development. 2005;132:89–104. doi: 10.1242/dev.01547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan L. Looking within the zebrafish to understand the tuberculous granuloma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013;783:251–266. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6111-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauta PR, Nayak B, Das S. Immune system and immune responses in fish and their role in comparative immunity study: a model for higher organisms. Immunol. Lett. 2012;148:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw SA, Trede NS. A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Dis. Model Mech. 2012;5:38–47. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbud MV, Shapiro IM. Notochordal cells in the adult intervertebral disc: new perspective on an old question. Crit. Rev. Eukary. Gene. Expr. 2011;21:29–41. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v21.i1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner N, Bercsenyi M, Orban L, Kolanczyk ME, Linke D, Brand M, Nusslein-Volhard C, Harris MP. Duplication of fgfr1 permits Fgf signaling to serve as a target for selection during domestication. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1642–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, Xie X, Byrne EH, McCarroll SA, Gaudet R, et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature. 2007;449:913–918. doi: 10.1038/nature06250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito D, Tanaka M. Comparative aspects of gonadal sex differentiation in medaka: a conserved role of developing oocytes in sexual canalization. Sex. Dev. 2009;3:99–107. doi: 10.1159/000223075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W, Braasch I, Meyer A. Adaptive sequence evolution in a color gene involved in the formation of the characteristic egg-dummies of male haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Biol. 2007;5:51. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambraus F, Fjelldal PG, Hansen T, Solberg M, Glover KA. Interdisciplinary Approaches in Fish Skeletal Biology. Tavira, Portugal: Apr 22–24, 2013. A field study on occurrence of vertebral deformities in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) from two rivers in Western Norway. Abstract 58. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Setiadi E, Tsumura S, Kassam D, Yamaoka K. Effect of saddleback syndrome and vertebral deformity on the body shape and size in hatchery-reared juvenile red spotted grouper, Epinephelus akaara (Perciformes: Serranidae): a geometric morphometric approach. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006;22:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sfakianakis DG, Koumoundouros G, Anezaki L, Divanach P, Kentouri M. Development of a saddleback-like syndrome in reared white seabream Diplodus sargus (Linnaeus, 1758) Aquaculture. 2003;217:673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Transcriptional profiling of the nucleus pulposus: say yes to notochord. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2010;12:117. doi: 10.1186/ar3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MD, Bell MA, Kingsley DM. Parallel genetic origins of pelvic reduction in vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13753–13758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604706103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieger D, Stein C, Neifer D, van der Sar AM, Leptin M. The role of gamma interferon in innate immunity in the zebrafish embryo. Dis. Model. Mech. 2009;2:571–581. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sison M, Cawker J, Buske C, Gerlai R. Fishing for genes influencing vertebrate behavior: zebrafish making headway. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2006;35:33–39. doi: 10.1038/laban0506-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaar-Jagalska BE. ZF-CANCER: developing high-throughput bioassays for human cancers in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:441–443. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2009.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoorendonk KM, Peterson-Maduro J, Renn J, Trowe T, Kranenbarg S, Winkler C, Schulte-Merker S. Retinoic acid and Cyp26b1 are critical regulators of osteogenesis in the axial skeleton. Development. 2008;135:3765–3774. doi: 10.1242/dev.024034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahle U, Bally-Cuif L, Kelsh R, Beis D, Mione M, Panula P, Figueras A, Gothilf Y, Brosamle C, Geisler R, et al. EuFishBioMed (COST Action BM0804): a European network to promote the use of small fishes in biomedical research. Zebrafish. 2012;9:90–93. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2012.0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C, Kim CH. Zebrafish as a model for infectious disease and immune function. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;25:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Hammond G, Roberts RJ, Manchester NJ. Spinal deformation in commercially cultured Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L.: a clinical and radiological study. J. Fish Dis. 2007;30:745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung YH, Kim JM, Kim HT, Lee J, Jeon J, Jin Y, Choi JH, Ban YH, Ha SJ, Kim CH, et al. Highly efficient gene knockout in mice and zebrafish with RNA-guided endonucleases. Genome Res. 2014;24:125–131. doi: 10.1101/gr.163394.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaim LE, Connolly LE, Volkman HE, Humbert O, Born DE, Ramakrishnan L. Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6108–6117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00887-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanhart LM, Cosentino CC, Diep CQ, Davidson AJ, de Caestecker M, Hukriede NA. Zebrafish kidney development: basic science to translational research. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo. Today. 2011;93:141–156. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]