Summary

Contributions from multiple cathepsins within endosomal antigen processing compartments are necessary to process antigenic proteins into antigenic peptides. Cysteine and aspartyl cathepsins have been known to digest antigenic proteins. A role for the serine protease, Cathepsin G (CatG), in this process has been described only recently, although CatG has long been known to be a granule-associated proteolytic enzyme of neutrophils. In line with a role for this enzyme in antigen presentation, CatG is found in endocytic compartments of a variety of antigen presenting cells. CatG is found in primary human monocytes, B cells, myeloid dendritic cells 1 (mDC1), mDC2, plasmacytoid DC (pDC), and murine microglia, but is not expressed in B cell lines or monocyte-derived DC. Purified CatG can be internalized into endocytic compartments in CatG non-expressing cells, widening the range of cells where this enzyme may play a role in antigen processing. Functional assays have implicated CatG as a critical enzyme in processing of several antigens and autoantigens. In this review, historical and recent data on CatG expression, distribution, function and involvement in disease will be summarized and discussed, with a focus on its role in antigen presentation and immune-related events.

Keywords: Cathepsin G, MHC class II, antigen processing, antigen presenting cells, MBP

CatG: a historical perspective

At the end of the 19th century, experiments with various tissues demonstrated destruction of proteins and tissues in alkaline and acid environments, consistent with the presence of endogenous proteases. In 1884, Metchnikoff proposed intracellular digestion as a mechanism for handling foreign particles (Metchnikoff, 1884). Four years later, Kossel reported unpublished observations of F. Müller, suggesting that purulent sputum digests fibrin in weakly alkaline solutions (Kossel, 1888). Protein degradation was also noted in liver and muscle tissue after incubation in chlorophorm water at 37°C, and Salkowski termed this “autodigestion” (Salkowski, 1890). Metchnikoff then proposed that mononuclear phagocytes, which he named macrophages, take up exogenous material by phagocytosis into vacuoles containing a proteolytic enzyme (macrocytase) (Metchnikoff, 1901). Soon thereafter, Hedin characterized two proteases in ox-derived spleen, the α-protease, active in alkali and the β-protease active in acid and suggested a functional role for these proteases in spleen cells (Hedin, 1904; Hedin, 1901). In 1929, Willstätter wrote, “Es läßt sich kaum umgehen, für die bei schwach saurer Reaktion wirkende Proteinase (Magenschleimhaut-Proteinase) einen besonderen Namen einzuführen; wir schlagen dafür die Bezeichnung Kathepsin vor, von καϑεψειν=verdauen” [it is indispensable to propose a name for a protease which reacts in a slightly acidic environment (gastric mucosa protease); we suggest for that the name cathepsin, (gr. to digest)]. He further proposed that cathepsin had its origin in leukocytes and was secreted after autolysis (Willstätter, 1929). In 1960, evidence suggested at least three distinct proteases in leukocytes, two from lymphocytes and active at pH 3 and pH 5, respectively; the other, with chymotrypsin-like activity, was present in PMN (Mounter and Atiyeh, 1960). In 1970, an enzyme from swine leukocytes was named cathepsin G because it degraded α-, β-, and γ-globulin, as compared to cathepsin F, which hydrolyzed fibrin (Lebez and Kopitar, 1970). However, it is not clear whether this activity was CatG or another protease active at pH 6.5, such as CatS, in part because the activity was purified as a protein >15 kDa, which might favor CatS (20 kDa) over CatG (28.5 kDa). In 1975, three highly cationic proteins from azurophilic granules of neutrophils were observed as fast migrating major bands by gel electrophoresis (Dewald et al., 1975). Concurrently, an activity with antibacterial properties was found in granulocytes and called chymothrypsin-like enzyme, based on its chymotrypsin-like activity (Rindler-Ludwig and Braunsteiner, 1975). In 1976, Starkey et al. described a chymotrypsin-like enzyme, active at alkaline pH, purified from human spleen and visualized as two bands (~28 KDa) by reducing SDS-PAGE; this activity was identified as a serine protease and called cathepsin G (Starkey and Barrett, 1976).

Cathepsin G: gene and protein

CatG is an endoprotease that belongs to the S1 class of serine proteases. The CatG gene (CTSG) is located on chromosome 14q11.2 and exhibits a genomic structure similar to that of neutrophil elastase (NE), with five exons and four introns, covering 2.7 kbp of genomic DNA. Exon 2 encodes the active site histidine (H), exon 3 the aspartic acid (D), and exon 5 the serine (S), which together form the catalytic triad of CatG. Cis-acting sequences of CTSG include a CAAT box (position -69) and a TATA box (position -29) (Hohn et al., 1989).

CatG gene expression is restricted to cells of the myeloid lineage (Grisolano et al., 1994) and developmentally regulated: high levels of CatG mRNA in promyelocytes diminish as the neutrophil matures (Garwicz et al., 2005). Similarly, in a promonocytic cell line, U937, differentiation stimulated by phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetat (TPA), reduces CatG mRNA expression (Hanson et al., 1990). CatG transcripts are not detected in human monocytes by in situ hybridization (Hanson et al., 1990), but have been detected by qPCR (Burster et al., 2005).

The protein product of the CTSG gene is a 255 amino acid polypeptide, representing preproCatG. After cleavage of the signal peptide, two amino acids remain at the N-terminal side of proCatG, which can be released by CatC. The observation that CatG-activity is not found in a CatC knockout mouse demonstrates that CatC is crucial for activation of CatG (Adkison et al., 2002). The C-terminal extension of 11 amino acids is digested by an unknown protease (McGuire et al., 1993; Salvesen et al., 1987). There are several isoforms of CatG: C1, C2, and C3 all contain one N-glycosylation site at asparagine-64 (N64) where a combination of fucose, mannose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, and N-acetylneuraminic acid, are added; C4 is not glycosylated (Watorek et al., 1993). Functional differences between these isoforms have not been defined.

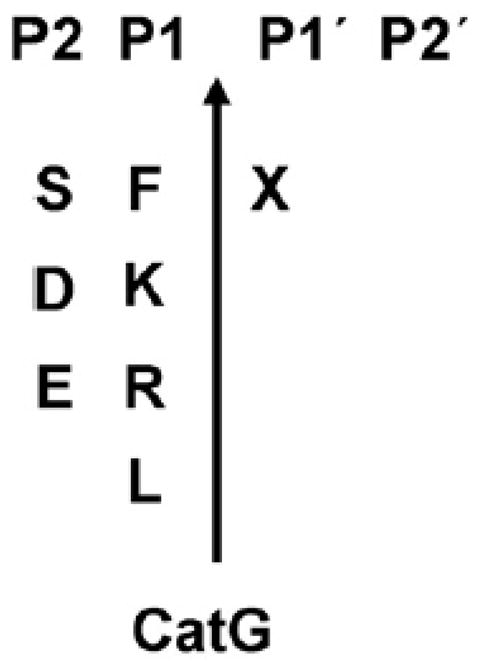

CatG has chymotrypsin-and trypsin-like activity and has activity across a broad pH spectrum (optimal between pH 7-8). The catalytic triad of aspartate, histidine and serine residues forms the CatG active site that hydrolyzes a peptide bond precisely after aromatic and strongly positively charged residues (F, K, R, or L) in the P1 position (Wysocka et al., 2007). At the P1′ position every amino acid is apparently accepted, although serine and an acidic residue is preferred at P2′ (Figure 1) (Rehault et al., 1999).

Figure 1. Substrate specificity of CatG.

Clevage site of the protease is determined between P1 and P1′position. X=represent all 20 amino acids.

Cathepsin G in neutrophils: a brief overview

CatG is best known as one of three serine proteases, neutrophil elastase (NE), CatG, and proteinase 3 (PR3), expressed in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils (Baggiolini et al., 1978; Baggiolini et al., 1979). These proteases are thought to be critically important in maintaining the delicate balance between tissue protection and destruction during an inflammatory response. They are involved in a broad range of functions in neutrophlis, including clearance of internalized pathogens, proteolytic modification of chemokines and cytokines, activation as well as shedding of cell surface receptors and apoptosis (reviewed in (Meyer-Hoffert, 2009; Nathan, 2006; Pham, 2006; Pham, 2008).

The anti-microbial activities of CatG and PR3 include both proteolysis-dependent and independent mechanisms, in contrast to NE, whose anti-bacterial activity is limited to proteolytic cleavage of membrane proteins of Gram-negative bacteria (Cole et al., 2001; Korkmaz et al., 2008; Ohlsson et al., 1977). The region of CatG including amino acids 117-136 is arginine-rich, and these cationic residues interfere with the negatively-charged bacterial surface in a proteolytic independent way (Odeberg and Olsson, 1975; Shafer et al., 1996; Shafer and Onunka, 1989; Shafer et al., 1986). Consistent with its anti-microbial activity, CatG deficiency in gene-targeted mice increases susceptibility to Staphylococcus aureus and fungal infections (Reeves et al., 2002; Tkalcevic et al., 2000).

CatG also has important effects that regulate chemotaxis. It cleaves the N-terminal residues of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (CXCL5) and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 (CCL15) to generate more potent chemotactic factors for neutrophils and monocytes, respectively (Nufer et al., 1999; Richter et al., 2005). CatG (and NE) converts prochemerin to chemerin, a novel chemoattractant for APC (Wittamer et al., 2005). The secretion of the chemotactic factor CXCL2 by neutrophils also depends on the action of CatG (Raptis et al., 2005). In opposing effects, CatG degrades chemokines CCL5, CCL3, CXCL12 and the chemokine receptor, CXCR4 (reviewed in (Pham, 2008).

CatG and the other 2 neutrophil serine proteases are stored in azurophil granules in active form. They are secreted in limited amount following certain stimuli (Bank and Ansorge, 2001; Meier et al., 1985). It is generally believed that the secreted proteases remain bound and active on the cell surface membrane (Owen and Campbell, 1999a; Owen and Campbell, 1999b). There, CatG can increase integrin clustering, which regulates neutrophil effector functions (Raptis et al., 2005). Secreted CatG and γ-secretase also cleave CD43 from the neutrophil cell surface, which may be important for cell migration (Mambole et al., 2008). In the circulation, most soluble serine proteases are probably bound in a 1:1 stoichiometry with serine protease inhibitors (serpins) (Medema et al., 2001; Remold-O’Donnell et al., 1992). However, in the extravascular environment, they may escape inhibition and bind to other cells. For example, CatG binds to and activates protease activated receptor 4 (PAR4) on platelets, influencing neutrophil-platelet interactions at sites of inflammation (Sambrano et al., 2000). Overall, the proteolytic activities of neutrophil associated CatG are many and have significant immune-related effects, including host defense. It will be of interest in future studies to determine which of these activities are shared by APCs where CatG is found in endocytic compartments that are akin to azurophilic granules.

Antigen presenting cells

B cells, macrophages, microglia, and dendritic cells (DC) are professional antigen presenting cells (APC). DC, the APC par excellence, often serve as a link between the innate and adaptive immunity and play a key role in maintaining tolerance (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998). Based on the location, activation status and function, DC are divided into three different categories: conventional DC, plasmacytoid DC (pDC) and inflammatory DC, respectively (for review (Shortman and Naik, 2007; Villadangos and Schnorrer, 2007)).

Antigen processing and presentation by professional APC

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules together with the MHC II-associated invariant chain (Ii), p31 (~31 kDa, li1-216) and the splice variant p41 (~41 kDa, li1-280), are expressed and assembled in the ER, forming a nonameric (αβIi)3-complex. Trafficking through endocytic compartments, li of the (αβIi)3-complex is C-terminal sequentially degraded into the N-terminal containing intermediates p22 (~22 kDa), p18 (~18 kDa), p10 (~10 kDa, li1-104), and finally to class II-associated Ii peptide (CLIP, ~3 kDa, li81-104) fragment. It is now clear that CatS plays a central role in converting p10 into CLIP in DC (Riese et al., 1996; Villadangos et al., 1997), however, it remains uncertain, which proteases are involved in the initial step of li processing and the respective cleavage site. The remaining CLIP-peptide occupies the MHC class II binding groove, preventing premature loading of antigenic peptides (Busch et al., 2005; Chapman, 2006; Villadangos et al., 2005; Watts, 2004). The MHC-related molecule HLA-DM noncovalently catalyzes the exchange of CLIP from the binding groove of MHC class II molecules for more stable peptides to form peptide/MHC II-complexes (reviewed in (Busch et al., 2005). These complexes are transported to the cell surface, for presentation to the T cell receptor (TCR) of CD4+ T cells (Maynard et al., 2005).

Less molecular detail is known about the processes involved in generating the ligands that replace CLIP. APC, in particular DC, are capable of taking up foreign antigens, as well as autoantigens, into endocytic compartments (endosomes and lysosomes) to be digested into appropriate fragments for loading to MHC class II molecules and subsequent presentation to CD4+ T cells. The endocytic compartments contain antigen processing machinery, including reducing agents (such as gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase, GILT) and proteases, specifically different classes of cathepsins. The cathepsins degrade both MHC II-associated invariant chain (Ii) to class II-associated Ii peptide (CLIP) and endosomally-delivered proteins into peptides for binding to MHC class II molecules (Busch et al., 2005; Chapman, 2006; Villadangos et al., 2005; Watts, 2004).

Cathepsins of the cysteine and aspartyl protease classes

According to the amino acid within their active site, cathepsins are divided into three classes: cysteine, aspartyl, and serine. At the active site of cysteine cathepsins, histidine and asparagine residues polarize the cysteine residue, which carries out nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of an amide bond (Chapman et al., 1997). The cysteine cathepsins of the CA clan include CatB, C, F, H, S, L, V, and X. Together with the CD clan-associated asparagine endoprotease (AEP), the cysteine proteases are involved in antigen and li processing and have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (Bromme et al., 1999; Chapman, 2006; Colbert et al., 2009; Manoury et al., 2002b; Rudensky and Beers, 2006; Shi et al., 2000; Turk et al., 2000; Villadangos and Ploegh, 2000; Watts et al., 2005; Zavasnik-Bergant and Turk, 2006).

CatD and CatE, members of the aspartyl protease family, also participate in antigen processing. CatD is expressed in all cells (except erythrocytes), whereas CatE expression is restricted to APC (Bennett et al., 1992; Burster et al., 2008; Chain et al., 2005; Hewitt et al., 1997; Moss et al., 2005; Zaidi et al., 2007). In APC, CatE is localized to endosomes, while CatD is primarily located in lysosomes (for review see (Zaidi and Kalbacher, 2008)). Less is known about the serine protease CatG in antigen processing. This enzyme and its function in APC is the main focus of this review.

Distribution and function of CatG within APC

1. CatG expression by the professionals

The ability to process proteins into antigenic peptides requires the concerted action of multiple cathepsins in all APC. However, the specific expression pattern of cathepsins varies in different APC. CatG is found in primary human B cells, both subsets of DC (mDC1 and mDC2), cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTEC), and at maximum levels in pDC (summarized in Table 1). In the mouse, CatG is expressed in microglia and splenic DC. However, CatG is not found in B lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLC), monocyte-derived DC, and fibroblast cell lines. This indicates an important functional difference between primary cells and certain model antigen presenting cells and highlighting the value of assessing antigen processing in primary cells (Burster et al., 2004; Burster et al., 2005; Stoeckle et al., 2009).

Table 1. Summary of CatG transcripts, protein, and activity in various human APC and murine microglia.

| APC | Function | CatG RNA | CatG Protein | CatG Activity | CatC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cells | B cells | ||||

| CD19 B cell | CD19 is a co-receptor of B cell receptor (BCR), expressed during B cell development, but lost on plasma cells. | + (9) | + * | + (9) | - (9) |

| CD22 B cell | CD22 is an inhibitory co-receptor of B cell receptor (BCR)-mediated signaling, found on mature peripheral blood B cells and lost during differentiation to plasma cells. ~5 % of PBMC. | - (5) | + (5) | + (5) | - (6) |

| BLC | B lymphoblastoid cells are immortalized B cells, generated by EBV transformation. | - (5) | - (5) | - (5) | + (6) |

| DC | Dendritic cells | ||||

| mDC1 | Myeloid DC1, express surface markers CD1c, CD2, CD4, CD13, CD33, CD45RO, and CD64 and represent ~0.6 % of PBMC. | + (7, 9) | + (7) | + (7, 9) | - (7) |

| mDC2 | Myeloid DC2, a rare blood DC subset, express surface markers CD4, CD13, CD33, and CD141 and recognize glycoproteins via mannose receptor C type 2. Approximately 0.04% of PBMC are mDC2. | n.a. | n.a. | + (9) | - (9) |

| pDC | Plasmacytoid DC, express surface markers CD4, CD45RA, CD123, CD303, and CD304, and represent ~0.2 % of PBMC. They are less differentiated than tissue pDC, but can produce high amounts of IFN-α after microbial stimulation. | + (9) | ++ * | ++ (9) | - (9) |

| MoDC | Monocyte-derived DC are generated ex vivo from monocytes by using GM-CSF and IL-4 for 6 days. | + (7) | ++ (7) | - (7) | + (7) |

| CD14 | CD14+ monocytes represent 10–15 % of PBMC and can differentiate into macrophages or DC upon egress into the tissues, depending on the cytokine milieu. | + (7, 10) | ++ (2) | ++ (7) | - (4) |

| PMN | Polymorphonuclear leukocytes | - (3) | +++ (1) | +++ (1) | + (4) |

| cTEC | Cortical thymic epithelial cells are responsible for early thymocyte development and positive selection. | n.a. | + (9) | n.a. | n.a. |

| microglia | Microglia are glial cells of the brain with phagocytic and antigen presenting capacity. | + (8) | + (8) | + (8) | n.a. |

CD19/CD22, primary B cells; BLC, B-lymphoblastoid cells; mDC, myeloid dendritic cells; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; MoDC, monocyte-derived DC; CD14, monocytes; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (granulocytes); cTEC, cortical thymic epithelial cells; microglia, murine microglia. +++ very high; ++ high; + modestly; - not found; n.a. not available;

Burster unpublished data.

Senior et al., 1984;

Rao et al., 1997;

Lautwein et al., 2004;

Shapiro et al., 1991.

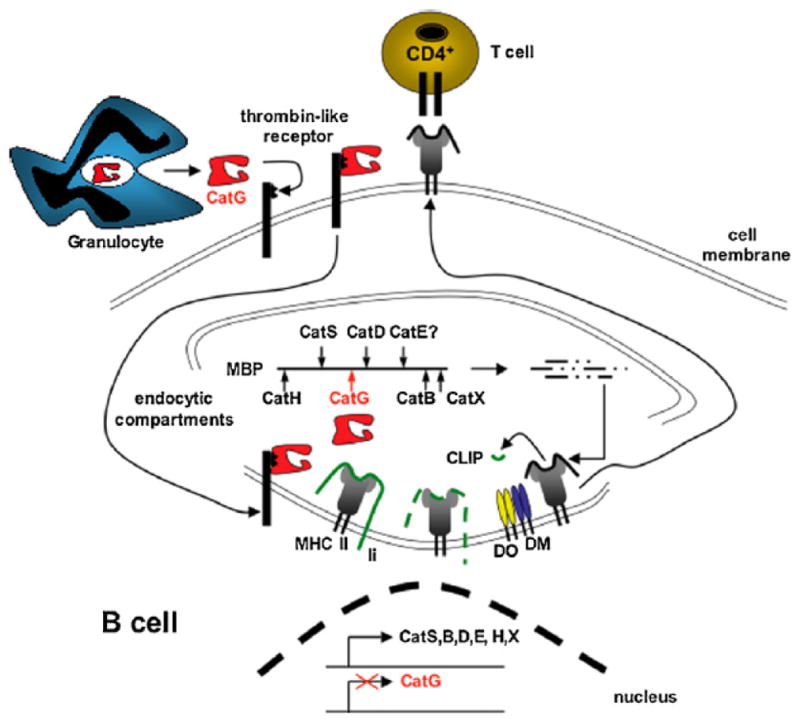

Primary human mDC1, pDC, and CD19+ B cells express CatG endogenously (Stoeckle et al., 2009). CatG is not endogenously synthesized in primary CD22+ B cells as CatG transcripts are not detectable in these cells (Burster et al., 2004). However, cells without endogenous expression of CatG can take up the secreted form of this enzyme. Purified CatG binds to a thrombin-like receptor at the cell surface of lymphocytes, including CD4+, CD8+, NK, and B cells (Yamazaki and Aoki, 1997). CatG binding to its receptor is specific and reversible. Interestingly, the serine protease inhibitor phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) partly interferes with the interaction of CatG with the receptor, implicating the active conformation of CatG in the mechanism of receptor binding (Yamazaki and Aoki, 1997). Data from purified B cells indicate that the surface CatG receptor is not constitutively saturated in circulating B cells and can bind more CatG from the serum (Delgado et al., 2001). CatG becomes active when bound to the receptor of lymphocytes (Owen and Campbell, 1998; Owen et al., 1995b). Indeed, when added to cultures of CatG non-expressing B lymphoblastoid cells, purified CatG is internalized into endocytic compartments, suggesting that B cells may upgrade their protease repertoire and antigen processing capacity from exogenous sources (summarized in Figure 2 and (Burster et al., 2004). The paradigm that additional proteases from exogenous origin can contribute to the antigen processing compartment is not without precedent, as was previously shown for AEP (Li et al., 2003).

Figure 2. A model of antigen processing in primary CD22+ B cells.

Activated granulocytes secret CatG into the plasma. CatG non-expressing, circulating B cells bind CatG via a thrombin-like receptor and internalize CatG into endocytic compartments. In these compartments, CatG functions as an additional protease and may improve the generation of antigenic ligands that replace CLIP on MHC class II molecules, a process facilitated by DM. The resulting MHC class II-antigenic peptide complex traffics to the cell surface for inspection by CD4+ T cells.

Cat, cathepsin; CLIP, class II-associated Ii peptides; DM, HLA-DM; DO, HLA-DO; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; li, MHC class II invariant chain; MBP, myelin basic protein; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

2. Antigen processing by CatG in different APC

Studies first implicating CatG as an important antigen processing enzyme focused on the processing of myelin basic protein (MBP) as a model autoantigen. MBP is one of several key autoantigens associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (also myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) and proteolipid protein (PLP)). The cationic arginine residues of MBP interact with the negatively-charged phosphate groups of lipid bilayers, ensuring adhesiveness between the lipid layers and forming the myelin sheath (for review, see (Stoeckle and Tolosa, 2009). In initial studies of MBP processing, CatG activity was not assessed, because its absence from BLC suggested it did not contribute to the antigen processing machinery. CatS and AEP were found to control MBP processing in BLC (Beck et al., 2001; Manoury et al., 2002a), However, the processing of MBP with lysosomal proteases derived from primary human B cells differed from that observed with BLC (Burster et al., 2004). Indeed, MBP digestion by primary B cell-derived lysosomal proteases was not impaired using an MBP mutant lacking the AEP cleavage site. Biochemical characterization of primary B cells showed that neither AEP protein nor AEP activity was present in these cells (Burster et al., 2004).

To examine CatG as a potential protease involved in MBP processing, we incubated MBP with purified CatG and analyzed the resulting fragments using HPLC, mass spectrometry, and micro-sequencing. We found that CatG cleaves this protein, and its processing site is in the middle of the MBP immunodominant epitope (MBP85-99) between phenylalanine 90 (F90) and lysine (K91). Consistent with this finding, when B cells and MBP84-98-reactive T cells were incubated with in vitro CatG-digested MBP, T cell proliferation was reduced to background levels (Burster et al., 2004). When CatG-preloaded fibroblasts are pulsed with MBP, diminished MBP84-98-specific T cell proliferation also results (Stoeckle et al., 2009). As fibroblasts do not express CatG, these data indicate that endocytosed CatG is also functional in antigen processing. CatG generates a second T cell epitope, MBP115-123, by hydrolyzing the peptide bond between phenylalanine 114 and serine 115. Thus, CatG can both destroy and generate specific T cell epitopes (Burster et al., 2004) (for AEP also see (Watts et al., 2003). We obtained the same CatG fragmentation pattern using lysosomal proteases from primary human B cells, suggesting a dominant role of CatG in processing of MBP by these cells (Burster et al., 2004).

In another study, we observed distinct fragmentation of MBP and MOG by human mDC1 lysosomal proteases compared to lysosomal proteases of monocyte-derived DC. CatG controlled the turnover of MBP and MOG by mDC1 lysosomal proteases. mDC1 lack significant amounts of active CatL, CatC, and AEP. In contrast, with lysosomal proteases from monocyte-derived DC, MBP, and MOG processing was dominated by CatS, CatD, and AEP (Burster et al., 2005). These differences in the endocytic proteolytic machinery between in vitro generated monocyte-derived DC and primary mDC demonstrate a potential limitation of using monocyte-derived DC to predict in vivo processing of antigens (Delamarre et al., 2005; Dudziak et al., 2007). Our results also indicate that AEP is dispensable for processing of MBP in primary human B cells and mDC1. AEP is expressed in pDC and mDC2 (Stoeckle et al., 2009), in line with the possibility that pDC represent pre-DC, which are thought to have higher protease activity, facilitating antigen processing in these cells.

Data showing reduced presentation of hemagglutinin (HA) and tetanus toxin C-fragment (TTC) after uptake of the specific CatG-inhibitor were also obtained (Reich et al., 2009). Definitive evidence of the biological importance of these functional findings with CatG will require investigation in animal models, such as CatG knockout mice (Tkalcevic et al., 2000).

3. Regulation of CatG in APC

Microglia cells represent a functionally important APC in the CNS (Gonzalez-Scarano and Baltuch, 1999). When murine microglia are treated with IFN-γ to mimic a proinflammatory cytokine milieu, CatG is downregulated, whereas the activities of CatS, CatB, CatL, CatD, and AEP are unchanged. Furthermore, when lysosomal cathepsins from IFN-γ-treated murine microglia are incubated with MBP, the stability of MBP is increased compared to incubation with cathepsins from control cells. The differences in MBP processing are eliminated when a serine protease inhibitor, PMSF, is added, suggesting that IFN-γ mediated reductions in active CatG alter the processing of MBP (Burster et al., 2007). Regulation of CatG activity was also observed in human monocyte-derived DC during culture in IL-4 and GM-CSF; monocyte-derived DC at day five of culture contain CatG-activity, but CatG decreases after day seven (Ishri et al., 2004). Indeed, using the activity-based probe peptidyl (α-aminoalkyl) phosphonate diphenyl ester (DAP022c (Oleksyszyn and Powers, 1991)) to visualize active CatG, no CatG activity is detected in monocyte-derived DC, cultured for six days. CatG activity is not upregulated in monocyte-derived DC (day 6) after stimulation with LPS, IFN-γ, or TNF-α for 24 h (Burster et al., 2005). We also found reduced CatG-activity, when primary mDC1 were activated with LPS and analyzed with the DAP022c activity-based probe for serine proteases (Burster unpublished data). Other cell types increase CatG after cytokine treatment. For instance, TNF-α stimulates higher levels of CatG in HeLa cells and increases cell surface levels and secretion of CatG in PMN (Eliassen et al., 2000; McGettrick et al., 2001; Owen et al., 1995a). Therefore, regulation of CatG depends not only on the activation stimuli, but also on the type of APC. Cytokine regulation of CatG activity in antigen presenting cells and its relationship to antigen processing/presentation warrants further investigation.

4. Protein degradation by CatG

In addition to processing MBP, MOG, TTC, HA, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D)-associated autoantigen (Boehm et al., 2009; Burster et al., 2005; Reich et al., 2009), CatG at the surface of mononuclear cells has been shown to digest cell surface proteins. For example, CatG on the cell surface of blood lymphocytes cleaves and inactivates surface chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), which acts as a maturation factor for B cell-precursors (Delgado et al., 2001). In addition, soluble forms of CD2, CD4, CD87, IgG, IgM, elastine, and VCAM-1 have been shown to be generated by CatG-mediated cleavage at the cell surface (Baici et al., 1982a; Baici et al., 1982b; Boudier et al., 1991). Interestingly, CatG is thought to contribute to the inflammatory response (Miyata et al., 2007), but also cleaves CD14, a receptor for LPS, and reduces its cell surface expression (Le-Barillec et al., 2000). CatG also degrades CD2 at the T cell surface, leading to a temporary inhibition of chronic inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis (Doring et al., 1995). Further, CatG degrades TNF-α into two fragments (Scuderi et al., 1991) and activates TGF-b signal transduction (Wilson et al., 2009). By regulating levels of CD14, CD2, and TNF-α, CatG may have anti-inflammatory properties.

5. Diseases associated with CatG

To date, there are no diseases that have been shown to derive directly from mutation of CatG. However, mutation of CatC, which digests two amino acids from proCatG to generate mature CatG, is associated with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome (PLS) (Castori et al., 2009; Hart et al., 1999; Ochiai et al., 2009; Pham et al., 2004; Toomes et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2007). PLS is an extremely rare genetic disorder characterized by severe peridonontitis and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPK), which is marked thickening of the epidermis on the palms and soles (Gorlin et al., 1964; Hart and Shapira, 1994). The role of CatC in the pathogenesis of PLS and PPK is not well understood.

A discreet role in disease pathogenesis for CatG as an antigen processing enzyme has not been described. However, substantial evidence implicates CatG (along with NE and PR-3) from neutrophil granules in a number of inflammatory processes. For example, increased levels of CatG, correlating with neutrophil count, are found in synovial fluid and tissue in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and contribute to chemotactic activity for monocytes (Miyata et al., 2007). Notably, mice deficient in CatC and CatG are resistant to experimental arthritis (Adkison et al., 2002; Hu and Pham, 2005). Neutrophil serine proteases also contribute to various lung disorders (Kamp et al., 1993; Nygaard et al., 1993; Okrent et al., 1990; Peterson et al., 1995; Van Wetering et al., 1997). Co-administration of CatG and NE cause emphysema and bronchial secretory cell metaplasia in a hamster model (Lucey et al., 1985), and inhaled CatG induces airway hyperresponsiveness, a signature feature of asthma, in a rat model, (Coyle et al., 1994). In investigations related to cardiovascular disease, CatG inactivates (Anderssen et al., 1993; Turkington, 1991) or activates coagulation factors (Allen and Tracy, 1995; Gale and Rozenshteyn, 2008), and induces platelet activation and aggregation (LaRosa et al., 1994; Molino et al., 1992; Selak and Smith, 1990). CatG also might induce cardiac injury (Sabri et al., 2003). CatG activity likely also influences the tumor environment. For example, at the mammary tumor-bone interface, CatG enhances osteoclast activation and subsequent bone resorption (Wilson et al., 2008).

Conclusion

Improved understanding of antigen processing in the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway is of fundamental interest and is needed for CD4+ T cell epitope prediction. One contribution to this effort will be investigating the degradation of various proteins using specific cathepsin inhibitors to determine the roles of the numerous proteases found in the endocytic compartments. We have reviewed findings on the serine protease CatG within antigen presenting cells. CatG, like other cathepsins, is differentially expressed within various APC types. CatG is found and functional in primary human monocytes, B cells, mDC1, mDC2, pDC, and murine microglia and purified CatG can be internalized into endocytic compartments in CatG non-expressing cells to expand their protease repertoire. Elucidation of the contributions of specific proteases in specific APC types will be necessary to inhibit epitope generation in particular APCs as a strategy for therapeutic immunomodulation. It will be important to consider CatG in the design of these future studies in intra- as well as extracellular antigen processing, in microbial defense and inflammatory settings.

Abbreviations

- AEP

asparagine endopeptidase

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- BLC

B-lymphoblastoid cells

- Cat

cathepsin

- CCL15

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15

- CLIP

class II-associated Ii peptides

- cTEC

cortical thymic epithelial cells

- CXCL5

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5

- GILT

gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- mDC

myeloid dendritic cells

- Ii

MHC class II invariant chain

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NE

neutrophil elastase

- PAR4

protease activated receptor 4

- PKK

palmoplantar hyperkeratosis

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- PLP

proteolipid protein

- PLS

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- PMSF

phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride

- PR3

proteinase 3

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor 1

- TPA

phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetat

- TCR

T cell receptor

- T1D

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- TTC

tetanus toxin C-fragment

References

- Adkison AM, Raptis SZ, Kelley DG, Pham CT. Dipeptidyl peptidase I activates neutrophil-derived serine proteases and regulates the development of acute experimental arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:363–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DH, Tracy PB. Human coagulation factor V is activated to the functional cofactor by elastase and cathepsin G expressed at the monocyte surface. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1408–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderssen T, Halvorsen H, Bajaj SP, Osterud B. Human leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G inactivate factor VII by limited proteolysis. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:414–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M, Bretz U, Dewald B, Feigenson ME. The polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Agents Actions. 1978;8:3–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01972395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M, Schnyder J, Bretz U, Dewald B, Ruch W. Cellular mechanisms of proteinase release from inflammatory cells and the degradation of extracellular proteins. Ciba Found Symp. 1979:105–21. doi: 10.1002/9780470720585.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baici A, Knopfel M, Fehr K. Cathepsin G from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes cleaves human IgM. Mol Immunol. 1982a;19:719–27. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(82)90373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baici A, Knopfel M, Fehr K. Cleavage of the four human IgG subclasses with cathepsin G. Scand J Immunol. 1982b;16:487–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank U, Ansorge S. More than destructive: neutrophil-derived serine proteases in cytokine bioactivity control. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H, Schwarz G, Schroter CJ, Deeg M, Baier D, Stevanovic S, Weber E, Driessen C, Kalbacher H. Cathepsin S and an asparagine-specific endoprotease dominate the proteolytic processing of human myelin basic protein in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3726–36. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3726::aid-immu3726>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K, Levine T, Ellis JS, Peanasky RJ, Samloff IM, Kay J, Chain BM. Antigen processing for presentation by class II major histocompatibility complex requires cleavage by cathepsin E. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1519–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm BO, Rosinger S, Sauer G, Manfras BJ, Palesch D, Schiekofer S, Kalbacher H, Burster T. Protease-resistant human GAD-derived altered peptide ligands decrease TNF-alpha and IL-17 production in peripheral blood cells from patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2576–2584. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudier C, Godeau G, Hornebeck W, Robert L, Bieth JG. The elastolytic activity of cathepsin G: an ex vivo study with dermal elastin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:497–503. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.6.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromme D, Li Z, Barnes M, Mehler E. Human cathepsin V functional expression, tissue distribution, electrostatic surface potential, enzymatic characterization, and chromosomal localization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2377–85. doi: 10.1021/bi982175f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burster T, Beck A, Poeschel S, Oren A, Baechle D, Reich M, Roetzschke O, Falk K, Boehm BO, Youssef S, Kalbacher H, Overkleeft H, Tolosa E, Driessen C. Interferon-gamma regulates cathepsin G activity in microglia-derived lysosomes and controls the proteolytic processing of myelin basic protein in vitro. Immunology. 2007;121:82–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burster T, Beck A, Tolosa E, Marin-Esteban V, Rotzschke O, Falk K, Lautwein A, Reich M, Brandenburg J, Schwarz G, Wiendl H, Melms A, Lehmann R, Stevanovic S, Kalbacher H, Driessen C. Cathepsin G, and not the asparagine-specific endoprotease, controls the processing of myelin basic protein in lysosomes from human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172:5495–503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burster T, Beck A, Tolosa E, Schnorrer P, Weissert R, Reich M, Kraus M, Kalbacher H, Haring HU, Weber E, Overkleeft H, Driessen C. Differential processing of autoantigens in lysosomes from human monocyte-derived and peripheral blood dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5940–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burster T, Reich M, Zaidi N, Voelter W, Boehm BO, Kalbacher H. Cathepsin E regulates the presentation of tetanus toxin C-fragment in PMA activated primary human B cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch R, Rinderknecht CH, Roh S, Lee AW, Harding JJ, Burster T, Hornell TM, Mellins ED. Achieving stability through editing and chaperoning: regulation of MHC class II peptide binding and expression. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:242–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castori M, Madonna S, Giannetti L, Floriddia G, Milioto M, Amato S, Castiglia D. Novel CTSC mutations in a patient with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome with recurrent pyoderma and minimal oral and palmoplantar involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:881–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain BM, Free P, Medd P, Swetman C, Tabor AB, Terrazzini N. The expression and function of cathepsin E in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1791–800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman HA. Endosomal proteases in antigen presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman HA, Riese RJ, Shi GP. Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:63–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert JD, Matthews SP, Miller G, Watts C. Diverse regulatory roles for lysosomal proteases in the immune response. Eur J Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/eji.200939650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole AM, Shi J, Ceccarelli A, Kim YH, Park A, Ganz T. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase prevents cathelicidin activation and impairs clearance of bacteria from wounds. Blood. 2001;97:297–304. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle AJ, Uchida D, Ackerman SJ, Mitzner W, Irvin CG. Role of cationic proteins in the airway. Hyperresponsiveness due to airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:S63–71. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/150.5_Pt_2.S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamarre L, Pack M, Chang H, Mellman I, Trombetta ES. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science. 2005;307:1630–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1108003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MB, Clark-Lewis I, Loetscher P, Langen H, Thelen M, Baggiolini M, Wolf M. Rapid inactivation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 by cathepsin G associated with lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:699–707. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<699::aid-immu699>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald B, Rindler-Ludwig R, Bretz U, Baggiolini M. Subcellular localization and heterogeneity of neutral proteases in neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1975;141:709–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.4.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doring G, Frank F, Boudier C, Herbert S, Fleischer B, Bellon G. Cleavage of lymphocyte surface antigens CD2, CD4, and CD8 by polymorphonuclear leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Immunol. 1995;154:4842–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliassen LT, Rekdal O, Svendsen JS, Osterud B. TNF 41-62 and TNF 78-96 have distinct effects on LPS-induced tissue factor activity and the production of cytokines in human blood cells. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale AJ, Rozenshteyn D. Cathepsin G, a leukocyte protease, activates coagulation factor VIII. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:44–51. doi: 10.1160/TH07-08-0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garwicz D, Lennartsson A, Jacobsen SE, Gullberg U, Lindmark A. Biosynthetic profiles of neutrophil serine proteases in a human bone marrow-derived cellular myeloid differentiation model. Haematologica. 2005;90:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Scarano F, Baltuch G. Microglia as mediators of inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:219–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlin RJ, Sedano H, Anderson VE. The Syndrome of Palmar-Plantar Hyperkeratosis and Premature Periodontal Destruction of the Teeth. a Clinical and Genetic Analysis of the Papillon-Lef’evre Syndrome. J Pediatr. 1964;65:895–908. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(64)80014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisolano JL, Sclar GM, Ley TJ. Early myeloid cell-specific expression of the human cathepsin G gene in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8989–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RD, Connolly NL, Burnett D, Campbell EJ, Senior RM, Ley TJ. Developmental regulation of the human cathepsin G gene in myelomonocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1524–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TC, Hart PS, Bowden DW, Michalec MD, Callison SA, Walker SJ, Zhang Y, Firatli E. Mutations of the cathepsin C gene are responsible for Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Med Genet. 1999;36:881–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TC, Shapira L. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. Periodontol 2000. 1994;6:88–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin SG. Investigations on the proteolytic enzymes of the spleen of the ox. J of Physiol. 1904;30:155–175. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1903.sp000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin SGaR. Zeit f phys Chem. 1901:xxxii, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt EW, Treumann A, Morrice N, Tatnell PJ, Kay J, Watts C. Natural processing sites for human cathepsin E and cathepsin D in tetanus toxin: implications for T cell epitope generation. J Immunol. 1997;159:4693–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohn PA, Popescu NC, Hanson RD, Salvesen G, Ley TJ. Genomic organization and chromosomal localization of the human cathepsin G gene. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13412–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Pham CT. Dipeptidyl peptidase I regulates the development of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2553–8. doi: 10.1002/art.21192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishri RK, Menzies S, Hersey P, Halliday GM. Rapid downregulation of antigen processing enzymes in ex vivo generated human monocyte derived dendritic cells occur endogenously in extended cultures. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:239–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2004.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp DW, Dunne M, Dykewicz MS, Sbalchiero JS, Weitzman SA, Dunn MM. Asbestos-induced injury to cultured human pulmonary epithelial-like cells: role of neutrophil elastase. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:73–80. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz B, Moreau T, Gauthier F. Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G: physicochemical properties, activity and physiopathological functions. Biochimie. 2008;90:227–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossel Zeit f klin Med. 1888:xiii, 149. [Google Scholar]

- LaRosa CA, Rohrer MJ, Benoit SE, Rodino LJ, Barnard MR, Michelson AD. Human neutrophil cathepsin G is a potent platelet activator. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:306–18. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70106-7. discussion 318–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le-Barillec K, Pidard D, Balloy V, Chignard M. Human neutrophil cathepsin G down-regulates LPS-mediated monocyte activation through CD14 proteolysis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebez D, Kopitar M. Leucocyte proteinases. I. Low molecular weight cathepsins of F and G type. Enzymologia. 1970;39:271–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DN, Matthews SP, Antoniou AN, Mazzeo D, Watts C. Multistep autoactivation of asparaginyl endopeptidase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38980–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey EC, Stone PJ, Breuer R, Christensen TG, Calore JD, Catanese A, Franzblau C, Snider GL. Effect of combined human neutrophil cathepsin G and elastase on induction of secretory cell metaplasia and emphysema in hamsters, with in vitro observations on elastolysis by these enzymes. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:362–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mambole A, Baruch D, Nusbaum P, Bigot S, Suzuki M, Lesavre P, Fukuda M, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. The cleavage of neutrophil leukosialin (CD43) by cathepsin G releases its extracellular domain and triggers its intramembrane proteolysis by presenilin/gamma-secretase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23627–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710286200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Mazzeo D, Fugger L, Viner N, Ponsford M, Streeter H, Mazza G, Wraith DC, Watts C. Destructive processing by asparagine endopeptidase limits presentation of a dominant T cell epitope in MBP. Nat Immunol. 2002a;3:169–174. doi: 10.1038/ni754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Mazzeo D, Fugger L, Viner N, Ponsford M, Streeter H, Mazza G, Wraith DC, Watts C. Destructive processing by asparagine endopeptidase limits presentation of a dominant T cell epitope in MBP. Nat Immunol. 2002b;3:169–74. doi: 10.1038/ni754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard J, Petersson K, Wilson DH, Adams EJ, Blondelle SE, Boulanger MJ, Wilson DB, Garcia KC. Structure of an autoimmune T cell receptor complexed with class II peptide-MHC: insights into MHC bias and antigen specificity. Immunity. 2005;22:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGettrick AF, Barnes RC, Worrall DM. SCCA2 inhibits TNF-mediated apoptosis in transfected HeLa cells. The reactive centre loop sequence is essential for this function and TNF-induced cathepsin G is a candidate target. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5868–75. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MJ, Lipsky PE, Thiele DL. Generation of active myeloid and lymphoid granule serine proteases requires processing by the granule thiol protease dipeptidyl peptidase I. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2458–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema JP, Schuurhuis DH, Rea D, van Tongeren J, de Jong J, Bres SA, Laban S, Toes RE, Toebes M, Schumacher TN, Bladergroen BA, Ossendorp F, Kummer JA, Melief CJ, Offringa R. Expression of the serpin serine protease inhibitor 6 protects dendritic cells from cytotoxic T lymphocyte-induced apoptosis: differential modulation by T helper type 1 and type 2 cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:657–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier HL, Heck LW, Schulman ES, MacGlashan DW., Jr Purified human mast cells and basophils release human elastase and cathepsin G by an IgE-mediated mechanism. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;77:179–83. doi: 10.1159/000233779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metchnikoff E. Über die pathologische Bedeutung der intrazellulären Verdauung. Fortschr Med. 1884;17:558–569. [Google Scholar]

- Metchnikoff E. L’immunite dans les maladies infectieuses. Paris, Masson. 1901:600. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Hoffert U. Neutrophil-derived serine proteases modulate innate immune responses. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3409–18. doi: 10.2741/3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata J, Tani K, Sato K, Otsuka S, Urata T, Lkhagvaa B, Furukawa C, Sano N, Sone S. Cathepsin G: the significance in rheumatoid arthritis as a monocyte chemoattractant. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molino M, Di Lallo M, de Gaetano G, Cerletti C. Intracellular Ca2+ rise in human platelets induced by polymorphonuclear-leucocyte-derived cathepsin G. Biochem J. 1992;288 (Pt 3):741–5. doi: 10.1042/bj2880741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss CX, Villadangos JA, Watts C. Destructive potential of the aspartyl protease cathepsin D in MHC class II-restricted antigen processing. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3442–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounter LA, Atiyeh W. Proteases of human leukocytes. Blood. 1960;15:52–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nufer O, Corbett M, Walz A. Amino-terminal processing of chemokine ENA-78 regulates biological activity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:636–42. doi: 10.1021/bi981294s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard SD, Ganz T, Peterson MW. Defensins reduce the barrier integrity of a cultured epithelial monolayer without cytotoxicity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:193–200. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai T, Nakano H, Rokunohe D, Akasaka E, Toyomaki Y, Mitsuhashi Y, Sawamura D. Novel p.M1T and recurrent p.G301S mutations in cathepsin C in a Japanese patient with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: implications for understanding the genotype/phenotype relationship. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:73–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeberg H, Olsson I. Antibacterial activity of cationic proteins from human granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:1118–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI108186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson K, Olsson I, Spitznagel K. Localization of chymotrypsin-like cationic protein, collagenase and elastase in azurophil granules of human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1977;358:361–6. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1977.358.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okrent DG, Lichtenstein AK, Ganz T. Direct cytotoxicity of polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule proteins to human lung-derived cells and endothelial cells. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:179–85. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleksyszyn J, Powers JC. Irreversible inhibition of serine proteases by peptide derivatives of (alpha-aminoalkyl)phosphonate diphenyl esters. Biochemistry. 1991;30:485–93. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell EJ. Angiotensin II generation at the cell surface of activated neutrophils: novel cathepsin G-mediated catalytic activity that is resistant to inhibition. J Immunol. 1998;160:1436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell EJ. Extracellular proteolysis: new paradigms for an old paradox. J Lab Clin Med. 1999a;134:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell EJ. The cell biology of leukocyte-mediated proteolysis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999b;65:137–50. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell MA, Boukedes SS, Campbell EJ. Inducible binding of bioactive cathepsin G to the cell surface of neutrophils. A novel mechanism for mediating extracellular catalytic activity of cathepsin G. J Immunol. 1995a;155:5803–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell MA, Sannes PL, Boukedes SS, Campbell EJ. Cell surface-bound elastase and cathepsin G on human neutrophils: a novel, non-oxidative mechanism by which neutrophils focus and preserve catalytic activity of serine proteinases. J Cell Biol. 1995b;131:775–89. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MW, Walter ME, Nygaard SD. Effect of neutrophil mediators on epithelial permeability. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:719–27. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham CT. Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:541–50. doi: 10.1038/nri1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham CT. Neutrophil serine proteases fine-tune the inflammatory response. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1317–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham CT, Ivanovich JL, Raptis SZ, Zehnbauer B, Ley TJ. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: correlating the molecular, cellular, and clinical consequences of cathepsin C/dipeptidyl peptidase I deficiency in humans. J Immunol. 2004;173:7277–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raptis SZ, Shapiro SD, Simmons PM, Cheng AM, Pham CT. Serine protease cathepsin G regulates adhesion-dependent neutrophil effector functions by modulating integrin clustering. Immunity. 2005;22:679–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, Messina CG, Bolsover S, Gabella G, Potma EO, Warley A, Roes J, Segal AW. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature. 2002;416:291–7. doi: 10.1038/416291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehault S, Brillard-Bourdet M, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Gauthier F, Moreau T. New, sensitive fluorogenic substrates for human cathepsin G based on the sequence of serpin-reactive site loops. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13810–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Lesner A, Legowska A, Sienczyk M, Oleksyszyn J, Boehm BO, Burster T. Application of specific cell permeable cathepsin G inhibitors resulted in reduced antigen processing in primary dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2994–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remold-O’Donnell E, Chin J, Alberts M. Sequence and molecular characterization of human monocyte/neutrophil elastase inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5635–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter R, Bistrian R, Escher S, Forssmann WG, Vakili J, Henschler R, Spodsberg N, Frimpong-Boateng A, Forssmann U. Quantum proteolytic activation of chemokine CCL15 by neutrophil granulocytes modulates mononuclear cell adhesiveness. J Immunol. 2005;175:1599–608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese RJ, Wolf PR, Bromme D, Natkin LR, Villadangos JA, Ploegh HL, Chapman HA. Essential role for cathepsin S in MHC class II-associated invariant chain processing and peptide loading. Immunity. 1996;4:357–66. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindler-Ludwig R, Braunsteiner H. Cationic proteins from human neutrophil granulocytes. Evidence for their chymotrypsin-like properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;379:606–17. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudensky A, Beers C. Lysosomal cysteine proteases and antigen presentation. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2006:81–95. doi: 10.1007/3-540-37673-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri A, Alcott SG, Elouardighi H, Pak E, Derian C, Andrade-Gordon P, Kinnally K, Steinberg SF. Neutrophil cathepsin G promotes detachment-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via a protease-activated receptor-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23944–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkowski Zeit f klin Med. 1890:xvii, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen G, Farley D, Shuman J, Przybyla A, Reilly C, Travis J. Molecular cloning of human cathepsin G: structural similarity to mast cell and cytotoxic T lymphocyte proteinases. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2289–93. doi: 10.1021/bi00382a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrano GR, Huang W, Faruqi T, Mahrus S, Craik C, Coughlin SR. Cathepsin G activates protease-activated receptor-4 in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6819–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi P, Nez PA, Duerr ML, Wong BJ, Valdez CM. Cathepsin-G and leukocyte elastase inactivate human tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin. Cell Immunol. 1991;135:299–313. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90275-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Smith JB. Cathepsin G binding to human platelets. Evidence for a specific receptor. Biochem J. 1990;266:55–62. doi: 10.1042/bj2660055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Hubalek F, Huang M, Pohl J. Bactericidal activity of a synthetic peptide (CG 117-136) of human lysosomal cathepsin G is dependent on arginine content. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4842–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4842-4845.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Onunka VC. Mechanism of staphylococcal resistance to non-oxidative antimicrobial action of neutrophils: importance of pH and ionic strength in determining the bactericidal action of cathepsin G. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:825–30. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-4-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WM, Onunka VC, Martin LE. Antigonococcal activity of human neutrophil cathepsin G. Infect Immun. 1986;54:184–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.184-188.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi GP, Bryant RA, Riese R, Verhelst S, Driessen C, Li Z, Bromme D, Ploegh HL, Chapman HA. Role for cathepsin F in invariant chain processing and major histocompatibility complex class II peptide loading by macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1177–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey PM, Barrett AJ. Human cathepsin G. Catalytic and immunological properties. Biochem J. 1976;155:273–8. doi: 10.1042/bj1550273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckle C, Sommandas V, Adamopoulou E, Belisle K, Schiekofer S, Melms A, Weber E, Driessen C, Boehm BO, Tolosa E, Burster T. Cathepsin G is differentially expressed in primary human antigen-presenting cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;255:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckle C, Tolosa E. Antigen Processing and Presentation in Multiple Sclerosis. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2009 doi: 10.1007/400_2009_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkalcevic J, Novelli M, Phylactides M, Iredale JP, Segal AW, Roes J. Impaired immunity and enhanced resistance to endotoxin in the absence of neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Immunity. 2000;12:201–10. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomes C, James J, Wood AJ, Wu CL, McCormick D, Lench N, Hewitt C, Moynihan L, Roberts E, Woods CG, Markham A, Wong M, Widmer R, Ghaffar KA, Pemberton M, Hussein IR, Temtamy SA, Davies R, Read AP, Sloan P, Dixon MJ, Thakker NS. Loss-of-function mutations in the cathepsin C gene result in periodontal disease and palmoplantar keratosis. Nat Genet. 1999;23:421–4. doi: 10.1038/70525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk B, Turk D, Turk V. Lysosomal cysteine proteases: more than scavengers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington PT. Degradation of human factor X by human polymorphonuclear leucocyte cathepsin G and elastase. Haemostasis. 1991;21:111–6. doi: 10.1159/000216213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wetering S, Mannesse-Lazeroms SP, Dijkman JH, Hiemstra PS. Effect of neutrophil serine proteinases and defensins on lung epithelial cells: modulation of cytotoxicity and IL-8 production. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:217–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadangos JA, Ploegh HL. Proteolysis in MHC class II antigen presentation: who’s in charge? Immunity. 2000;12:233–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadangos JA, Riese RJ, Peters C, Chapman HA, Ploegh HL. Degradation of mouse invariant chain: roles of cathepsins S and D and the influence of major histocompatibility complex polymorphism. J Exp Med. 1997;186:549–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P. Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:543–55. doi: 10.1038/nri2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P, Wilson NS. Control of MHC class II antigen presentation in dendritic cells: a balance between creative and destructive forces. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watorek W, van Halbeek H, Travis J. The isoforms of human neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G differ in their carbohydrate side chain structures. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1993;374:385–93. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1993.374.1-6.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C. The exogenous pathway for antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II and CD1 molecules. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:685–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Matthews SP, Mazzeo D, Manoury B, Moss CX. Asparaginyl endopeptidase: case history of a class II MHC compartment protease. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:218–28. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Moss CX, Mazzeo D, West MA, Matthews SP, Li DN, Manoury B. Creation versus destruction of T cell epitopes in the class II MHC pathway. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willstätter RaBE. Über die Proteasen der Magenschleimhaut. Erste Abhandlung über die Enzyme der Leukocyten. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chemie. 1929;180:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TJ, Nannuru KC, Futakuchi M, Sadanandam A, Singh RK. Cathepsin G enhances mammary tumor-induced osteolysis by generating soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5803–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TJ, Nannuru KC, Singh RK. Cathepsin G-mediated activation of pro-matrix metalloproteinase 9 at the tumor-bone interface promotes transforming growth factor-beta signaling and bone destruction. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1224–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V, Bondue B, Guillabert A, Vassart G, Parmentier M, Communi D. Neutrophil-mediated maturation of chemerin: a link between innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:487–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka M, Legowska A, Bulak E, Jaskiewicz A, Miecznikowska H, Lesner A, Rolka K. New chromogenic substrates of human neutrophil cathepsin G containing non-natural aromatic amino acid residues in position P(1) selected by combinatorial chemistry methods. Mol Divers. 2007;11:93–9. doi: 10.1007/s11030-007-9063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Aoki Y. Cathepsin G binds to human lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:73–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Bai X, Liu H, Li L, Cao C, Ge L. Novel mutations of cathepsin C gene in two Chinese patients with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Dent Res. 2007;86:735–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N, Burster T, Sommandas V, Herrmann T, Boehm BO, Driessen C, Voelter W, Kalbacher H. A novel cell penetrating aspartic protease inhibitor blocks processing and presentation of tetanus toxoid more efficiently than pepstatin A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N, Kalbacher H. Cathepsin E: a mini review. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavasnik-Bergant T, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins in the immune response. Tissue Antigens. 2006;67:349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]